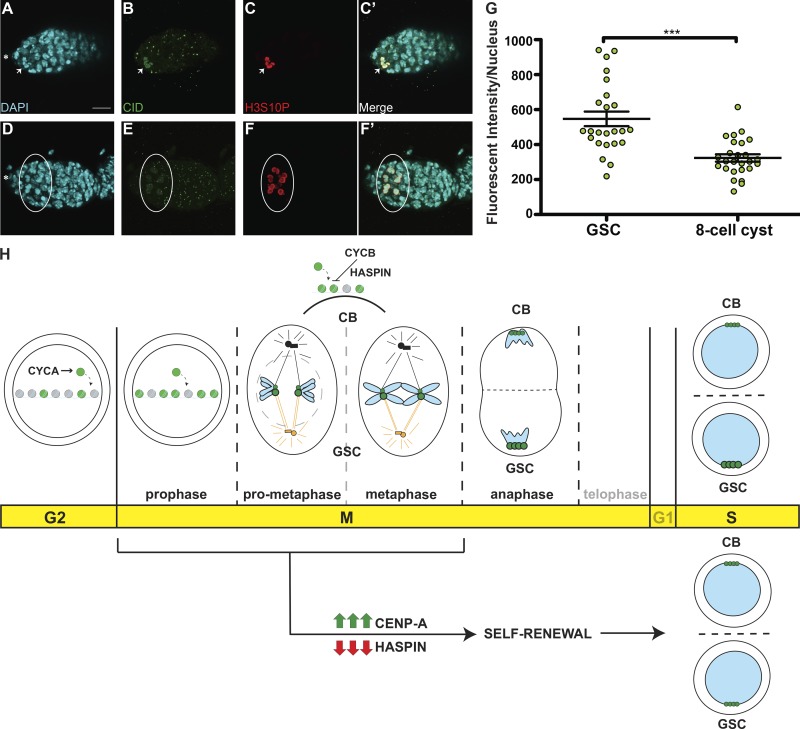

Figure 7.

Cyst cells incorporate less CID compared with GSCs. (A–F′) Confocal z-stack projection of a nanos-Gal4 germarium, stained for DAPI (cyan), anti-CID (green), and anti-H3S10P (red), to highlight a GSC (A–C′, arrow) and eight-cell cysts (D–F′, circle) in prophase. (G) Quantification of CID fluorescence intensity (integrated density) at centromeres in GSCs and eight-cell cysts at prophase obtained using wide-field microscopy. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM; ***, P < 0.0001. Star, terminal filament; 3-d-old female flies; scale bar, 10 µm. (H) Model for centromere assembly during the cell cycle. After replication, at early G2 phase, centromere assembly starts, promoted by CYCA, and centromeric nucleosomes (green) replace canonical nucleosomes (gray). This process continues until at least prophase. Excessive CID deposition is prevented by CYCB through HASPIN. At prometaphase, microtubules from centrosomes attach to centromeres through the kinetochore. At this point, sister chromatid pairs are loaded with differential amounts of CID (green) and CENP-C (not depicted) at centromeres. Chromosomes that retain more CID (bigger centromeres, figurative), make bigger kinetochores and attract more microtubules nucleating from the daughter centrosome (orange) and will be inherited by the GSC. At anaphase, and at replication, centromeres are clustered at the opposite sides of the two daughter nuclei. CID and CENP-C asymmetry is detected also at S phase. Telophase and G1 are shown as transparent because of the lack of data for these two phases. CID overexpression or HASPIN knockdown promotes GSC self-renewal and disrupts CID asymmetric inheritance.