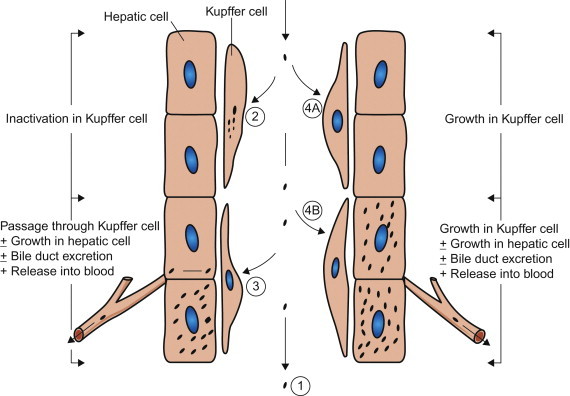

Figure 3.6.

Types of interaction between viruses and macrophages, exemplified by Kupffer cells, the macrophages that line the sinusoids in the liver. (1) Macrophages may fail to phagocytose virions; e.g., in Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus infection this is an important factor favoring prolonged high viremia. (2) Virions may be phagocytosed and destroyed: because the macrophage system is so efficient, viremia can be maintained only if virions enter the blood as fast as they are removed. (3) Virions may be phagocytosed and then transferred passively to adjacent cells (hepatocytes in the liver); e.g., in Rift Valley fever virus infection, the virus replicates in hepatocytes and causes severe hepatitis—the virus produced in the liver sustains the high viremia. (4) Virions may be phagocytosed by macrophages and then may replicate in them: (4A) with some viruses, such as lactate dehydrogenase elevating virus in mice, only macrophages are infected and progeny from that infection are the source of the extremely high viremia; (4B) more commonly, as in infectious canine hepatitis, the virus replicates in both macrophages and hepatocytes, producing severe hepatitis.

(Adapted from the work of C. A. Mims and D. O. White.)