Abstract

The role of macrophages in the innate immune response cannot be underscored however recent studies have demonstrated that both resident and recruited macrophages have critical roles in the pathogenesis of metabolic dysfunction. Given the recent data implicating exposure to persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases, the current study was designed to examine the effects of the highly implicated organochlorine (OC) compounds oxychlordane and trans-nonachlor on overall macrophage function. Murine J774A.1 macrophages were exposed to trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane (0 – 20 μM) for 24 hours then phagocytosis, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, mitochondrial membrane potential, caspase activities, pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and macrophage plasticity were assessed. Overall, exposure to oxychlordane significantly decreased macrophage phagocytosis while both OC compounds significantly increased ROS generation. Exposure to trans-nonachlor significantly increased secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-6 whereas oxychlordane had a biphasic effect on TNFα secretion. However, both oxychlordane and trans-nonachlor decreased basal expression of the M1 pro-inflammatory marker cyclooxygenase 2. Taken together, these data indicate that exposure to these two OC compounds have both compound and concentration dependent effects on macrophage function which may alter both the innate immune response and impact metabolic function of key organs involved in metabolic diseases.

Keywords: Trans-nonachlor, oxychlordane, persistent organic pollutant, macrophage, inflammation, phagocytosis

1. Introduction

Chronic low-level inflammation is a common symptom of an overactive immune response and is understood to be associated with metabolic diseases such as obesity and type 2 diabetes [for review see (Monteiro and Azevedo, 2010)]. Previous studies show that this could be caused by hypertrophy or overabundance of adipocytes in visceral white adipose tissue and the inflammation caused by the heightened immune response and recruitment of monocytes/macrophages to these depots (Chawla et al., 2011; Weisberg et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2003). While the macrophage phenotype can vary greatly and are most likely part of a spectrum of activity, there are two overall types of macrophages generally described, the classically activated (M1) macrophages that have a pro-inflammatory response, and the alternately activated (M2) macrophages which are typically anti-inflammatory in nature (Mantovani et al., 2005; Martinez and Gordon, 2014; Mosser and Edwards, 2008). M1 macrophages specifically are thought to play a major role in the chronic inflammatory process observed in states of metabolic dysfunction such as obesity and type 2 diabetes (Lumeng et al., 2007a; Lumeng et al., 2007b). Indeed, the crosstalk between macrophages and the metabolic response, recently termed metainflammation, is a key factor when looking at how diseases like type 2 diabetes and obesity can be caused or exuberated (Hotamisligil, 2006, 2017; Hotamisligil et al., 1993). Metabolically active cells such as adipocytes and hepatocytes are a common storage place for factors that can cause macrophage activation/proliferation such as free fatty acids and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Gordon and Martinez-Pomares, 2017).

Adipocytes and to a lesser extent hepatocytes are primary storage sites for the bioaccumulation of persistent organic pollutants (POPs). In general, POPs are lipophilic and typically have a long half-life allowing them to remain in the environment for long periods. Some examples of POPs include organochlorine (OC) pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) which are two broad classes of POPs that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases by epidemiological studies. Upon examination of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), Lee et al. (2006) determined that the prevalence of diabetes was highly correlated with the serum concentration of OC pesticides, including oxychlordane and trans-nonachlor (Lee et al., 2006). Subsequent work by this group revealed positive associations between OC pesticides and insulin resistance as well as increased prevalence of the metabolic syndrome including elevated fasting blood glucose levels and elevated circulating triacylglycerol levels (Lee et al., 2007a; Lee et al., 2007b). Similar results have been reported in both Swedish men and women indicating increased prevalence of diabetes following exposure to POPs (PCB-153 and DDE) as well as Great Lakes sport fish consumers (Rignell-Hydbom et al., 2007; Rylander et al., 2005; Turyk et al., 2009a; Turyk et al., 2009b). Additionally, elevated serum concentrations of POPs, including PCBs and OC pesticides, are associated with an increased prevalence of the metabolically unhealthy phenotype suggesting a POPs mediated conversion from the healthy to unhealthy phenotype (Gasull et al., 2018; Gauthier et al., 2014). A recent review of current epidemiological studies determined the strongest positive associations between POPs exposures and diabetes was for OC pesticides, including trans-nonachlor (Taylor et al., 2013). Thus, there is mounting evidence implicating POPs, including OC pesticides and their metabolites, in the pathogenesis of metabolic dysfunction.

While the causal relationship between POPs exposure and metabolic dysfunction has been the subject of active investigation in recent studies, the underlying mechanisms governing POPs-induced systemic metabolic dysfunction remain elusive. Previous in vitro and in vivo studies by our group have specifically focused on metabolic effects of exposure to OC pesticides or their bioaccumulative metabolites and have revealed alterations in both adipocyte and hepatocyte function. Specifically, exposure to the prevalent OC pesticide metabolite DDE was shown to increase adipogenesis and alter adipokine expression/production in vitro (Howell and Mangum, 2011; Mangum et al., 2015b). With regard to direct effects on hepatocyte function, recent studies with the OC compound trans-nonachlor have demonstrated a pro-steatotic effect of this compound which may be linked to increased de novo lipogenesis in vitro (Howell et al., 2018a, b). Recent in vivo studies have revealed acute exposure to DDE produces hyperglycemia whereas chronic DDE exposure in high fat fed mice produced a diet-dependent biphasic effect on fasting hyperglycemia (Howell et al., 2014a; Howell et al., 2014b). These in vivo data are reinforced by other rodent based studies examining either OC pesticides either alone or in an environmentally relevant mixture which have reinforced the link between OC pesticide exposure and systemic metabolic dysfunction (Ibrahim et al., 2011; Mulligan et al., 2017; Ruzzin et al., 2009).

Although direct effects on adipocytes and hepatocytes may promote metabolic dysfunction, POPs-induced alterations in metainflammation and specifically macrophage function, may represent a potential physiological mechanism through which exposures may exacerbate this underlying metabolic dysfunction. Previous studies have demonstrated that exposure to PCBs have divergent effects on systemic inflammation and macrophage function depending on if the specific PCB or mixture of PCBs are dioxin-like (DL) or non-dioxin like (NDL) with DL PCBs having a generally pro-inflammatory effect whereas NDL PCBs have a generally anti-inflammatory effect (May et al., 2018; Petriello et al., 2018; Santoro et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019). Regarding OC pesticides or their metabolites, there appears to be divergent compound specific effects. For example, Mangum et al. (2016) demonstrated that exposure to DDE produced largely anti-inflammatory effects as indicated by decreased pro-inflammatory prostaglandin production in murine J77 macrophages (Mangum et al., 2016). However, generally pro-inflammatory effects of the OC pesticides dieldrin and trans-nonachlor were noted in human THP-1 monocytes/macrophages as indicated by increased ROS production (Mangum et al., 2015a).

Given the recent studies implicating OC pesticide/compound exposure in the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases as well as the potential role of OC-induced alterations in macrophage function and metainflammation, the present study was designed to examine the concentration dependent effects of the highly implicated OC compounds trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane on overall macrophage function. The widely utilized murine J774A.1 macrophage cell line was employed as the in vitro model of macrophage function as has been performed in previous studies examining the effects of OC compounds on macrophage reactivity (Ferrante et al., 2011; Mangum et al., 2015a; Mangum et al., 2016; Santoro et al., 2015). Key aspects of macrophage function examined in the present study included cytotoxicity, phagocytosis of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) bioparticles, ROS generation, mitochondrial membrane potential, caspase activity, pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and macrophage plasticity/polarization.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

Trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane (>99% purity) were both purchased from AccuStandard (New Haven, CT) in the neat form. Stock solutions of trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane were made in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at 4000x for each concentration to be tested to produce a 0.025% concentration of DMSO as vehicle. 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluoroscein diacetate (DCFDA) and 5,6-dichloro-2-[3-(5,6-dichloro-1,3-diethyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzimidazol-2-ylidene)-1 -propen-1 -yl]-1,3-diethyl-1H-benzimidazolium monoiodide (JC-1) dyes as well as N-acetyl-L-α-aspartyl-L-α-glutamyl-L-valyl-N-(4-nitrophenyl)-L-asparagine (Ac-DEVD-pNA) and N-acetyl-L-tyrosyl-L-valyl-L-alanyl-N-(4-nitrophenyl)-L-α-asparagine (Ac-YVAD-pNA) substrates were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Cell Counting Kit-8 was obtained from Millipore-Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Molecular Probes CellROX Green and pHrodo-labelled S. aureus bioparticles were obtained from Thermo-Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

2.2. Cell culture and treatment

The murine macrophage cell line J774A.1 (J77) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Millipore-Sigma) with 10% fetal bovine serum, high glucose (4.5 g/L), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), glutamine (4 mM), and penicillin/streptomycin as normal growth media for routine culturing and passaging. To determine the effects of exposure to either trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane on macrophage function, J77 cells were seeded in multi-well tissue culture dishes at 0.3 × 106 cells/ml in normal growth media and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were then treated with either control (no DMSO), vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM), trans-nonachlor (0.02 – 20 μM), or oxychlordane (0.02 μM) for up to 24 hours in serum free growth media with 0.5% fatty acid free BSA. Following OC compound exposure for up to 24 hours, cells were subjected to assays to determine OC effects on cell viability, phagocytic activity, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), caspase activities, pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and macrophage polarization. It should be noted that there were no significant effects of the 0.025% DMSO vehicle compared to control (no DMSO) in any of these measured endpoints (data not shown).

2.3. Cell viability

The effects of both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane on cellular viability was performed as previously described (Howell et al., 2018b). Briefly, J77 cells were exposed to vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM), trans-nonachlor, or oxychlordane (0.02 – 20 μM; n=4/group) for 24 hours in phenol red free, serum free DMEM then viability was determined by cell viability reagent (Cell Counting Kit-8; Millipore-Sigma) per the manufacturer’s instructions. This reagent forms a water-soluble formazan dye from the tetrazolium salt WST-8 [2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium,monosodium salt] in the presence of live cells which is quantitated at 450 nm. Cellular viability data were expressed as the percent viability of vehicle treated cells.

2.4. Phagocytic activity

OC compound-induced alterations in macrophage phagocytosis and subsequent phagolysosome formation was measured by pHrodo labeled S. aureus bioparticles (ThermoFisher Scientific) given the increase in pHrodo fluorescence with decreasing pH. Briefly, J77 macrophages were seeded in 96-well black microplates then exposed to vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM), trans-nonachlor, or oxychlordane (0.02 – 20 μM; n=8/group) for 24 hours in serum-free growth media. Following exposure, cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) then incubated with pHrodo-labeled S. aureus bioparticles for up to 90 minutes at 37°C in phenol red free DMEM. Bioparticle uptake was measured by fluorescent plate reader every 15 minutes at an excitation of 530 nm and an emission of 590 nm. Data are expressed as the total bioparticle fluorescence following one hour of uptake per the manufacturer’s protocol with no cell background subtraction as well as the bioparticle fluorescence per minute to determine OC-induced alterations in uptake kinetics.

2.5. Detection of oxidative stress

Previous studies have determined that exposure to trans-nonachlor induces oxidative stress and subsequent production of reactive oxygen species in human macrophages (Mangum et al., 2015a). Thus, the concentration related effects of both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane on production of ROS were examined by two complimentary methods, DCFDA and CellROX fluorogenic probe assays. Briefly, J77 macrophages were treated with either vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM), trans-nonachlor, or oxychlordane (0.02 μM - 20 μM; n=8/group) for 24 hours in serum free DMEM as described above. During the last 2 hours of exposure, either DCFDA (20 μM) or CellROX (5 μM) in phenol red free DMEM. At the end of 24 hours, cellular fluorescence was measured (ex 485 nm/em 528 nm) by fluorescent plate reader to quantify intracellular ROS production. Data are expressed as the total probe fluorescence following background subtraction.

In addition to quantifying ROS production, cellular glutathione levels were determined to examine potential effects on cellular antioxidant capacity. Briefly, J77 macrophages (n=4/group) were treated with vehicle, trans-nonachlor, or oxychlordane as outlined above. Following exposure for 24 hours, cells were homogenized and homogenate (50 μl) glutathione levels were measured spectrophotometrically at 412 nm as previously described (Howell et al., 2018a, b). Data are expressed as cellular glutathione (μmole) per microgram of protein.

2.6. Mitochondrial membrane potential

To determine if increased ROS formation was related to alterations in mitochondrial membrane potential, J77 macrophages were subjected to JC-1 staining during OC compound exposure. Briefly, J77 macrophages were loaded with JC-1 dye (Cayman Chemical) at a final concentration of 20 μM in PBS (pH 7.4) for 15 minutes prior to OC compound exposure. Following JC-1 dye loading, cells were washed twice with PBS then treated with either vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM), trans-nonachlor, or oxychlordane (0.02 – 20 μM; n=7–8/group) for 24 hours in serum free growth media. Monolayers were then washed with PBS and both JC-1 monomer (ex 485 nm/em 528 nm) and JC-1 aggregate (ex 530 nm/em 590 nm) fluorescence was quantified via fluorescent spectrophotometer. The JC-1 monomer fluorescence indicates mitochondrial membrane depolarization whereas the JC-1 aggregate fluorescence indicates mitochondrial membrane hyperpolarization. Data are expressed as the aggregate:monomer ratio for each sample.

2.7. Caspase 1 and 3 activities

OC compound mediated effects on inflammasome activation and apoptosis were determined by measuring the activities of caspase 1 and caspase 3, respectively, via cleavage of enzyme specific substrates. Following exposure to OC compounds (n=6–9/group) for 24 hours, cells were collected in chilled cell lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 2 mg/ml leupeptin, and 2 mg/ml aprotinin) and incubated at 4°C for 20 minutes then subjected to 3 freeze/thaw cycles for lysis. Following lysis, the homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 minutes to pellet cellular debris. Supernatants were collected for caspase activity assays. To perform both caspase 1 and caspase 3 assays, 50 μl of cellular supernatant (200 μg protein) was combined with 50 μl of 2x reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 0.2% CHAPS, 20% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, and 10 mM DTT) containing 400 μM of either Ac-YVAD-pNA for caspase 1 activity or Ac-DEVD-pNA for caspase 3 activity. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for up to 1.5 hours with substrate absorbance (405 nm) being measured every 15 minutes to determine both kinetics of caspase activity as well as activity after 1 hour of incubation. Caspase activities were linear up to one hour of incubation. Data are expressed as the substrate absorbance at one hour and absorbance per minute following background (no cellular homogenate) subtraction.

2.8. Pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and secretion

The effects of OC compound exposure on macrophage inflammatory cytokine production, specifically the prominent pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) was determined following exposure to either vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM), trans-nonachlor, or oxychlordane (0.2 – 20 μM) for 24 hours in serum free growth media. These two pro-inflammatory cytokines were chosen given their established roles in the progression of a chronic inflammatory state as well as in the pathogenesis of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes. Effects on cytokine expression (n=4–6/group) were measured by real-time PCR as previously performed for adipokine expression with β-actin expression as housekeeping the gene (Howell and Mangum, 2011). In addition to cytokine gene expression, the secretion of both TNFα and IL-6 were determined in the cell culture supernatants (n=5–6/group for TNFα; n=4–6/group for IL-6) via ELISA (Biolegend ELISA MAX standard sets). Tnfα and IL-6 expression levels are expressed as the fold change from vehicle control and cell culture supernatant concentrations are expressed as the pg/ml of each cytokine in the cell culture media.

2.9. Macrophage polarization

A macrophage polarization assay with known M1 and M2 inducers was used to determine if exposure to the OC compounds trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane altered the ability of macrophages to be polarized toward an M1 -like pro-inflammatory or and M2-like housekeeping phenotype as previously performed (Mangum et al., 2016). Expression of the pro-inflammatory genes cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNos) were used as indicators of M1 –like phenotype whereas expression of the anti-inflammatory housekeeping gene arginase-1 (Arg-1) was used as an indicator of the M2-like phenotype as previously performed (Mangum et al., 2016).

To examine OC-induced alterations in basal polarity, J77 macrophages (n=8–9/group) were treated with vehicle (DMSO 0.025%), trans-nonachlor (2 μM), or oxychlordane (2 μM) in serum-free growth medium for 24 hours. The 2 μM concentration of trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane was chosen based on our current data indicating this concentration of each OC compound produced alterations in phagocytosis, DCFDA fluorescence, and cytokine production/expression in a compound specific manner. Following OC compound exposure, the expression of Cox-2, iNos, and Arg-1 was measured by real-time PCR with β-actin as the housekeeping gene and levels expressed via the δδCt method. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of the fold change from vehicle.

To determine if OC compound exposure altered induction of M1 or M2 polarization, J77 macrophages (n=4–6/group) were treated with vehicle (DMSO 0.025%), M1 inducers (100 ng/ml LPS + 20 ng/ml IFNγ), or M2 inducer (20 ng/ml IL-4) in the presence or absence of trans-nonachlor (2 μM) or oxychlordane (2 μM) for 24 hours as previously performed with minor modification (Mangum et al., 2016). Following M1 or M2 induction in the presence or absence of trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane, the expression of Cox-2 and Arg-1 was determined by real-time PCR as previously performed to evaluate OC alterations in M1 and M2 polarization, respectively. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of the fold change from vehicle.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM for each group and represent at least two independent experimental replications per group. The Grubb’s test was employed to determine if there was a statistical outlier in each experimental group with a power of α>0.05. For experiments with three or more groups, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s post hoc test (SigmaPlot v13) using pairwise comparisons was performed to determine statistically significant differences between groups. It should be noted that statistical analysis of real-time PCR data was performed on the δCt values and not the fold change values. A P-value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane on cell viability

The abilities of both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane to alter cellular viability in J77 macrophages was determined following exposure to a low nanomolar to low micromolar range of each compound for 24 hours. Exposure to trans-nonachlor (Figure 1A) or oxychlordane (Figure 1B) at the highest concentration (20 μM) did not significantly alter cellular viability compared to vehicle (0 μM). Thus, this concentration range was used in subsequent assays to evaluate effects of exposure to these two compounds on J77 function and reactivity.

Figure 1:

Exposure to trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane does not decrease cellular viability. J77 macrophages were exposed to either trans-nonachlor (A) or oxychlordane (B) in normal growth media for 24 hours then cellular viability was assessed. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of the percent of vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM) with n=4/group.

3.2. Oxychlordane significantly decreases phagocytosis of pHrodo labeled S. aureus

Given the critical role of macrophages in the phagocytosis and subsequent degradation of pathogenic bacteria in phagolysosomes, the effects of exposure to both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane on both total phagocytosis as well as rate of phagocytosis of pHrodo-labeled S. aureus particles was explored in J77 macrophages. Regarding total phagocytosis, exposure to trans-nonachlor displayed a concentration-dependent yet non-significant decrease with a maximal reduction of 28.6% compared to vehicle (0 μM) following exposure to 20 μM of trans-nonachlor for 24 hours (Figure 2A). Exposure to oxychlordane was much more potent compared to trans-nonachlor in terms of reducing total phagocytosis with significant concentration-dependent reductions of 54.1% and 65.8% following exposure to 2 μM or 20 μM of oxychlordane, respectively, when compared to vehicle (0 μM; Figure 2B).

Figure 2:

Oxychlordane significantly decreases pHrodo labeled S. aureus phagocytosis. Both total pHrodo labeled S. aureus fluorescence at one hour (A and B) as well as the rate of phagocytosis in the first hour (C and D) were assessed in J77 macrophages following exposure to either trans-nonachlor (A and C) or oxychlordane (B and D). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM total fluorescence at one hour (RFU @ 1 hour) or the rate of phagocytosis (RFU/min) with n=8/group. *P≤0.05 vs. vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM); #P≤0.05 vs. 0.2 μM

Trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane had similar effects on the rate of phagocytosis as compared to their respective effects of total phagocytosis. Exposure to trans-nonachlor for 24 hours produced a concentration-dependent yet non-significant reduction in the rate of S. aureus phagocytosis in J77 cells with a maximal reduction of 31% following exposure to 20 μM of trans-nonachlor (Figure 2C). As opposed to trans-nonachlor exposure, oxychlordane significantly reduced the rate of S. aureus phagocytosis in a concentration-dependent manner starting with 0.2 μM up to 20 μM (Figure 2D). Oxychlordane significantly reduced the rate of phagocytosis by 32.4%, 56.5%, and 78.7% following exposure to 0.2 μM, 2 μM, and 20 μM, respectively. Thus, as opposed to trans-nonachlor, exposure to oxychlordane significantly decreases both the rate of phagocytosis and total phagocytosis of S. aureus in J77 macrophages.

3.3. Trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane increase reactive oxygen species

Previous studies have demonstrated that exposure to trans-nonachlor can increase oxidative stress in THP-1 human macrophages (Mangum et al., 2015a). Thus, we explored the effects of both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane on the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in J77 macrophages using two complimentary assays, the DCFDA and CellROX assays, which are widely utilized indicators of non-specific ROS. Exposure to trans-nonachlor (2 μM) significantly increased DCFDA fluorescence by 28.8% compared to vehicle (0 μM; Figure 3A). However, exposure to oxychlordane produced a much more robust increase in DCFCA fluorescence with significant increases of 39.6%, 50.3%, 43.3%, and 65.8% following exposure to 0.02 μM, 0.2 μM, 2 μM, and 20 μM, respectively (Figure 3B). Similar increases were noted when ROS were measured via the CellROX assay. Trans-nonachlor (20 μM) exposure significantly increased CellROX fluorescence by 25.4% when compared to vehicle (0 μM; Figure 3C). Exposure to oxychlordane (Figure 3D) significantly increased CellROX fluorescence by 41.3% after exposure to 2 μM of oxychlordane and by 42.3% after exposure to 20 μM of oxychlordane. However, there was not a reciprocal decrease in cellular antioxidant status as indicated by cellular glutathione levels (Supplementary figure 1). Therefore, these data demonstrate that exposure to both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane can increase formation of ROS in J77 macrophages and that oxychlordane is more potent compared to trans-nonachlor in ROS generation.

Figure 3:

Exposure to trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane increase ROS generation. The formation of ROS was measured by both DCFDA (A and B) and CellROX (C and D) assays following exposure to either trans-nonachlor (A and C) or oxychlordane (B and D) for 24 hours in J77 macrophages. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM for DCFDA or CellROX fluorescence (RFU) with n=8/group for DCFDA and n=10–12/group for CellROX. *P≤0.05 vs. vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM)

3.4. Decreased mitochondrial membrane potential following trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane exposure

To determine if the observed increases in ROS following exposure to trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane were due in part to alterations in mitochondrial membrane polarity, J77 macrophages were subjected to JC-1 staining during OC compound exposures. Both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane produced comparable reductions in mitochondrial membrane potential, as indicated by the JC-1 aggregate:monomer ratios. Exposure to trans-nonachlor (20 μM) significantly reduced the mitochondrial membrane potential by 26.8% (Figure 4A) whereas exposure to oxychlordane (20 μM) significantly reduced the mitochondrial membrane potential by 29.2% (Figure 4B) compared to vehicle (0 μM). Thus, the potential arises that the increased ROS generated by the highest concentration of either trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane may be due, at least in part, to decreased mitochondrial membrane polarity.

Figure 4:

Trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane both decrease macrophage mitochondrial membrane potential. J77 macrophages were exposed to trans-nonachlor (A) or oxychlordane (B) for 24 hours then mitochondrial membrane potential was determined by JC-1 staining for the aggregate and monomer forms of JC-1. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of the ratio of JC-1 aggregate/monomer RFUs with n=7–8/group. *P≤0.05 vs. vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM)

3.5. Exposure to trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane decrease caspase-3 activity

Given the critical roles of caspases in macrophage function including inflammasome activation and apoptosis via caspase-1 and caspase-3 activities, respectively, the effects of OC exposure on these two major caspase isoforms was assessed via specific substrate cleavage assays. Exposure to trans-nonachlor (Figure 5A) or oxychlordane (Figure 5B) did not significantly alter the activity of caspase-1 in J77 macrophages. However, both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane significantly decreased caspase-3 activities. Exposure to trans-nonachlor (Figure 5C) significantly decreased caspase-3 activity by 27.8% and 27.4% when compared to vehicle (0 μM) following exposure to 2 μM or 20 μM, respectively. Unlike trans-nonachlor, oxychlordane (2 μM) did not significantly decrease caspase-3 activity (Figure 5D). However, exposure to oxychlordane (20 μM) significantly decreased caspase-3 activity by 74.7% compared to vehicle. Thus, the degree of suppression following oxychlordane (20 μM) was significantly greater than that observed following trans-nonachlor (20 μM) exposure.

Figure 5:

Exposure to trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane decrease caspase-3 but not caspase-1 activities. Caspase-1 (A and B) and caspase-3 (C and D) activities were determined in cell lysates from J77 macrophages exposed to either trans-nonachlor (A and C) or oxychlordane (B and D) for 24 hours with enzyme specific colorimetric substrates. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of the absorbance (405 nm) for either caspase-1 or caspase-3 specific substrates following 1 hour of incubation with n=6–9/group. *P≤0.05 vs. vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM)

3.6. Trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane promote pro-inflammatory cytokine production

Macrophage production and subsequent release is an essential component of the chronic, low-level inflammatory state as observed in various chronic disease states such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease as well as an essential component of the macrophage response to pathogen challenge. Therefore, the effects of OC compound exposure on secretion and expression of two key pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNFα and IL-6 was explored. Regarding cytokine secretion, exposure to trans-nonachlor significantly increased media levels of TNFα by 24.9% compared to vehicle (0 μM) whereas there was a significant concentration-dependent effect of oxychlordane on TNFα (Figure 6A). Oxychlordane significantly decreased media levels of TNFα by 28.6%, 30.9%, and 31.5% following exposure to 0.02 μM, 0.2 μM, and 2 μM, respectively, but significantly increased media levels of TNFα by 89.6% following exposure to 20 μM. While both OC compounds significantly altered TNFα levels, only trans-nonachlor (2 μM) significantly increased secretion of IL-6 as indicated by an increase in media IL-6 by 148.9% compared to vehicle (0 μM; Figure 6B). However, both oxychlordane and trans-nonachlor increased media levels of IL-6 at 20 μM of each compound but this trend was not statistically significant. It should be noted that IL-1β secretion in cell culture supernatants was explored as a potential pro - inflammatory mediator, but media levels were below the limit of detection in all groups for the ELISA kit (Mouse IL-1β DuoSet ELISA; R&D Systems).

Figure 6:

Exposure to trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane have differential effects on pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Secretion of both TNFα (A) and IL-6 (B) into the cell culture media by J77 macrophages following exposure to either trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane for 24 hours was determined by ELISA. Expression of both Tnfα and Il-6 in J77 macrophages following exposure to either trans-nonachlor (C) or oxychlordane (D) for 24 hours was determined by real-time PCR. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM for media cytokine levels in pg/ml with n=4–6/group for the cytokine secretion assays and as the mean ± SEM of the fold change from vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM) for J77 cytokine expression with n=4–6/group. *P≤0.05 vs. vehicle (0.025% DMSO; 0 μM); #P≤0.05 vs. 0.2 μM

When examining cellular production by alterations in gene expression, exposure to trans-nonachlor (20 μM) significantly increased the expression of both Tnfα and IL-6 by ~2.8 fold and ~3.8 fold, respectively, when compared to vehicle (0 μM; Figure 6C). In addition, trans-nonachlor (2 μM) significantly increased IL-6 expression by ~2.9 fold compared to vehicle (0 μM). As opposed to trans-nonachlor, exposure to oxychlordane did not significantly alter expression of either Tnfα or IL-6 (Figure 6D). Therefore, there was an OC compound specific effect on induction pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. Interestingly, the effects of oxychlordane on TNFα secretion as indicated by media levels, was not accompanied by significant alterations in gene expression at 24 hours which may indicate alterations in TNFα processing, release of stored TNFα, or that TNFα expression peaked prior to the current 24 hour sampling time point.

3.7. Alteration of macrophage polarization following trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane exposure

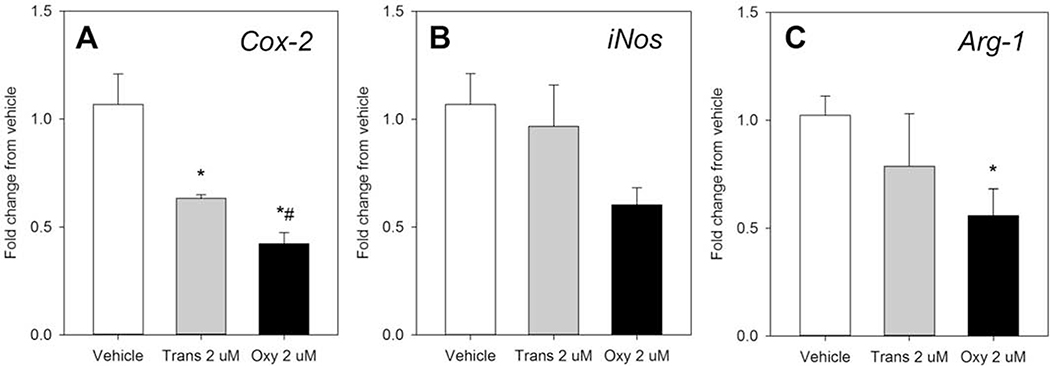

The effects of trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane on macrophage plasticity to be polarized towards a M1 -like pro-inflammatory or M2-like housekeeping phenotype was determined by macrophage polarization assay as previously described using expression of the M1 -like markers Cox-2 and iNos and the M2-like marker Arg-1 as indicators of polarization status. Following exposure to either trans-nonachlor (2 μM) or oxychlordane (2 μM) without the addition of polarization inducers, both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane significantly decreased expression of Cox-2 (Figure 7A) compared to vehicle (0 μM) and the degree of suppression following oxychlordane exposure was significantly greater than that of trans-nonachlor. A similar decrease in iNos expression (Figure 7B) was noted following oxychlordane exposure but this did not reach statistical significance. Interestingly, exposure to oxychlordane also significantly decreased expression of the M2-like marker Arg-1 (Figure 7C).

Figure 7:

Alterations in basal macrophage polarization following exposure to trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane. The effects of exposure to trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane for 24 hours on basal macrophage polarization with Cox-2 (A) and iNos (B) as M1 markers and Arg-1 (C) as a M2 marker. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of the fold change from vehicle (0.025% DMSO) with n=8–9/group. *P≤0.05 vs. vehicle (0.025% DMSO); #P≤0.05 vs. trans-nonachlor exposure

When OC compound effects were examined following induction with IFN + LPS to induce an M1 -like pro-inflammatory phenotype, exposure to oxychlordane (2 μM) significantly decreased IFN + LPS-induced expression of Cox-2 whereas there was no effect of trans-nonachlor (2 μM) on IFN + LPS-induced Cox-2 expression (Figure 8A). Conversely, exposure to trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane (2 μM) blunted IFN + LPS-induced reductions of Arg-1 expression (Figure 8C). Regarding M2-like polarization, exposure to trans-nonachlor (2 μM) appeared to blunt IL-4 mediated decreases in Cox-2 and iNos expression whereas exposure to oxychlordane (2 μM) did not appear to significantly alter IL-4 mediated suppression of these M1 markers (Figure 8D and 8E). Exposure to trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane (2 μM) had no significant effect on IL-4 induction of Arg-1 (Figure 8F).

Figure 8:

Alterations in M1 and M2 polarization following exposure to trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane. The effects of exposure to trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane in concert with either M1 (IFN + LPS; A-C) or M2 (IL4; D-F) activation on expression of the M1 (Cox-2 and iNos) or M2 (Arg-1) polarization markers. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of the fold change from vehicle (0.025% DMSO) with 4–6/group. *P≤0.05 vs. vehicle (0.025% DMSO); #P≤0.05 vs. trans-nonachlor exposure

In summary, both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane appear to significantly decrease Cox-2 expression when polarization agents are not employed. When polarized toward an M1 -like phenotype by IFN + LPS, oxychlordane significantly decreases IFN + LPS induction of Cox-2 expression and both OC compounds blunt IFN + LPS reduction of Arg-1 expression. When polarized toward an M2-like phenotype by IL-4, trans-nonachlor blunts IL-4 mediated reductions in the M1 markers Cox-2 and iNos but neither OC compound alter IL-4 mediated induction of the M2 marker Arg-1.

4. Discussion

While the role of macrophages in chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes has been intensively investigated, the augmentation of macrophage function by environmental exposures and subsequent effects on disease pathogenesis have not been fully elucidated. Specifically, the effects of exposure to OC pesticides on the spectrum of macrophage function and subsequent effects on disease pathogenesis remain elusive. Recent studies examining the effects of prominent OC pesticides or their metabolites, such as DDE, trans-nonachlor, and dieldrin, have revealed both compound and cell type specific effects on macrophage reactivity (Krzystyniak et al., 1989; Krzystyniak et al., 1987; Mangum et al., 2015a; Mangum et al., 2016). Thus, in the present study we examined both the compound specific and concentration-dependent effects of both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane on key aspects of macrophage function including phagocytosis, ROS generation, pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and macrophage polarization. These two OC compounds were chosen because they are either a metabolite or contaminant of technical chlordane as well as both have been routinely associated with metabolic dysfunction such as type 2 diabetes.

The concentrations employed in the present study range from low nanomolar to low micromolar concentrations of both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane. These concentrations were chosen to encompass serum and adipose tissue concentrations of these OC compounds. The most recently reported data from the NHANES study indicate that the weighted arithmetic mean of serum oxychlordane in non-Hispanic white males (20–39 years old) from 2013–2014 was 3.64 ng/g (lipid adjusted) whereas in comparably aged white females it was 4.4 ng/g (lipid adjusted) and these values increased 6.3-fold to 23.1 ng/g and 6.5-fold to 28.6 ng/g, respectively, when measured in the 60+ year old age bracket (CDC, 2019). Exposure data were comparable for non-Hispanic black males and females in the 20–39 year old age bracket with comparable increases upon aging with the exception of the non-Hispanic black females having a 12.8-fold increase in the 60+ year old age bracket compared to the 20–39 year old bracket (CDC, 2019). Serum concentrations of trans-nonachlor were higher than those of oxychlordane with non-Hispanic white males (20–39 years old) from 2013–2014 measuring 6.34 ng/g (lipid adjusted) whereas in comparably aged white females it was 7.62 ng/g following lipid adjustment (CDC, 2019). Trans-nonachlor values increased 6.6-fold to 42.1 ng/g and 6-fold to 45.5 ng/g in white males and females, respectively. As with oxychlordane, exposure data were comparable for non-Hispanic black males and females in the 20–39 year old age bracket with comparable increases upon aging with the exception of the non-Hispanic black females having a 13.4-fold increase in the 60+ year old age bracket (CDC, 2019). While lipid adjusted serum OC concentrations are intended to reflect the homeostasis between blood and adipose tissue, they do not account for fluctuations in serum concentrations upon weight loss. Following significant weight loss, serum concentrations of oxychlordane can increase an average of 2.9% per kilogram of weight reduction whereas serum concentrations of trans-nonachlor can increase an average of 2.8% per kilogram of weight reduction but have been reported to be as high as 5.4% and 5.2% per kilogram of weight reduction, respectively (Arguin et al., 2010; Jansen et al., 2017). Thus, circulating levels of these two OC compounds are in the low nanomolar range on average but can increase following significant weight loss which would be encompassed by our current concentration range.

One of the most prominent and vital functions of monocytes/macrophages is their phagocytic role in the host response to pathogen invasion. Specifically, macrophages exert a bactericidal effect on engulfed bacteria via fusion of the phagosome with the lysosome to form the phagolysosome which acidifies the pH of the phagosome and aids in the destruction phagocytosed pathogens (Flannagan et al., 2012). Our current data indicate exposure to oxychlordane significantly decrease both the rate of S. aureus pHrodo bioparticle phagolysosome formation as well as the total formation of S. aureus pHrodo bioparticle phagolysosome formation at 1 hour. This decrease in phagolysosome formation, as indicated by pHrodo-labelled S. aureus bioparticles, could potentially decrease the bactericidal efficacy of macrophages toward phagocytosed S. aureus given the innate ability of S. aureus to replicate intracellularly within the phagosome and potentially the phagolysosome (Flannagan et al., 2016). While our current data appear to be the first examining the effects of trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane individually on murine macrophage phagocytosis, Sitarska et al. (1990) reported a suppressive effect of an OC compound mixture, including prominent OC pesticides, on S. aureus phagocytosis by bovine macrophages and neutrophils (Sitarska et al., 1990). Additionally, Krzystyniak et al. demonstrated sublethal exposure to the OC pesticide dieldrin significantly decreased macrophage phagocytosis of Salmonella typhimurium as well as antigen presentation (Krzystyniak et al., 1989; Krzystyniak et al., 1987). Thus, these studies indicate that exposure to OC pesticides, including the chlordane metabolite oxychlordane, may significantly decrease the bactericidal efficacy of macrophages. However, a limitation of our current data is that the pHrodo-labelled S. aureus bioparticles are unable to determine if decreased phagolysosome formation is due to decreased phagocytosis or decreased phagosome/lysosome fusion.

Pro-inflammatory macrophages are characterized by increased formation of reactive oxygen species and increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production among other inflammatory mediators. To determine if exposure to trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane induced a pro-inflammatory phenotype in J77 macrophages, we first examined induction of oxidative stress and subsequent formation of ROS. Exposure to both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane induced concentration-dependent increases in intracellular ROS as indicated by increased DCFDA and CellROX fluorescence (Figure 3). While both OC compounds induced ROS, oxychlordane was more potent than trans-nonachlor as indicated by increased DCFDA and CellROX fluorescence at lower concentrations compared to trans-nonachlor. This increase in ROS was not accompanied by a decrease in cellular antioxidant capacity as indicated by cellular glutathione levels (Supplementary figure 1). However, our current data agree with previously published studies demonstrating trans-nonachlor induces oxidative stress and ROS in human THP-1 monocytes/macrophages at low micromolar concentrations (Mangum et al., 2015a). These previous studies by Mangum et al. (2015) implicate activation of NADPH oxidase in trans-nonachlor-mediated ROS production. While our current study did not address the role of NADPH oxidase in trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane induced ROS, we did evaluate effects on mitochondrial membrane polarity as a potential source of ROS generation. Both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane decreased mitochondrial membrane potential at the highest concentration of 20 μM indicating uncoupling of the mitochondrial membrane may contribute to trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane induced ROS at high concentrations. Thus, additional studies are warranted to further elucidate the source and specific type of ROS which are generated following exposure to both trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane. A noted limitation of the current study is that the present work was performed in a murine macrophage cell line. Future studies are necessary to determine if the presently observed effects of trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane occur in a human monocyte/macrophage cell line to aid in the translational extrapolation between murine and human effects following OC exposure.

As mentioned, a primary function of pro-inflammatory macrophages is to produce cytokines and chemokines which both initiate and propagate the inflammatory response of the innate immune system to pathogen challenge. Thus, we determined if exposure to trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane altered both expression and release of the major pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-6. Exposure to trans-nonachlor (2 μM) significantly increased secretion of both TNFα and IL-6 which was accompanied by an increase in expression of both cytokines at 20 μM and an increase in expression of IL-6 at 2 μM. Interestingly, exposure to oxychlordane had a concentration-dependent effect on TNFα secretion with the lower concentrations of oxychlordane (0.02 – 2 μM) significantly decreasing TNFα secretion whereas the highest concentration increased TNFα secretion. These oxychlordane-induced alterations of TNFα secretion were not associated with significant alterations in Tnfα expression indicating oxychlordane may exert the effects on TNFα secretion through altering TNFα processing for release (Black et al., 1997; Moss et al., 1997). However, the possibility arises that alterations in TNFα gene expression preceded the current 24 hour sampling time point. As previously mentioned, media levels of IL-1β were below the limit of detection via ELISA in all treatment groups. This lack of below the limit of detection level of IL-1β in concert with the lack of caspase-1 activation (Figure 5) indicates exposure to neither trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane activate the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway (He et al., 2016). Given the current studies were designed to assess the effects of exposure to trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane on basal macrophage function, the effects of exposure to these compounds on the macrophage cytokine response to an external pro-inflammatory stimulus cannot be directly inferred from the present studies and will thus be explored in our future studies.

It has recently come to the forefront that the spectrum of macrophage activation should not be limited to the traditional M1 or classically activated and the M2 or alternatively activated/polarized mantra (Martinez and Gordon, 2014). Thus, we will refer to these polarization states herein as M1 -like and M2-like. In the present study, we utilized expression of Cox-2, iNos, and Arg-1 as markers of M1 -like and M2-like polarization, respectively. These markers have been used in previous studies examining the effects of OC pesticide exposure, namely DDE, on macrophage polarization in J77 cells (Mangum et al., 2016). Our current data demonstrate that exposure to either oxychlordane or trans-nonachlor decrease basal Cox-2 expression which indicates a decrease in the M1 -like phenotype resting cells however there was no reciprocal increase in Arg-1 expression to indicate a flux toward the M2-like phenotype. The trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane mediated effects on basal Cox-2 expression are akin to those exerted by DDE on Cox-2 expression and subsequent prostaglandin production in J77 macrophages (Mangum et al., 2016). Regarding alterations in M1 or M2 induced polarization by IFNγ + LPS or IL-4, respectively, there was not a completely clear pattern of effect with either oxychlordane or trans-nonachlor in terms of reciprocal effects on the expression of Cox-2 or Arg-1 in the present study. For example, oxychlordane significantly blunted M1-like polarization by IFN + LPS as indicated by Cox-2 expression however there was not a corresponding inhibition of IFN + LPS-induced reduction of Arg-1 expression (Figure 8). Additionally, the current data demonstrating decreased phagocytosis/phagolysosome formation and decreased M1 marker expression (Cox-2) by oxychlordane are suggestive of an anti-inflammatory phenotype however oxychlordane significantly increased ROS formation and TNFα secretion at the highest concentration. Thus, the OC effects on macrophage function and phenotype could be divergent depending on the endpoint which is measured. The discrepancies in the current polarization assay highlight the complexity of the macrophage cellular phenotype as well as the need for further studies examining the effects of exposure to trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane on the alterations of macrophage function in the presence of both M1 and M2 polarization stimuli to assess if exposures to these compounds alter macrophage plasticity.

In summary, the current data indicate exposure to trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane have both compound and concentration-dependent effects on key aspects of macrophage function at concentrations which span the range of potential serum to bioaccumulative tissue levels. Decreased phagocytosis or phagolysosome formation following exposure to oxychlordane and to a lesser extent trans-nonachlor may decrease macrophage mediated bactericidal activities. Given the present increases in ROS formation as well as increased inflammatory cytokine secretion following exposure to trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane implicates the push toward a pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype which may promote a chronic inflammatory state as observed prevalence diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. However, the effects on inflammatory cytokine secretion, namely TNFα, by oxychlordane appear to be concentration dependent with inhibitory effects on TNFα at lower concentrations. Additionally, the effects of trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane exposure on macrophage plasticity, as indicated by the present polarization assay, may not be clearly toward an exclusive M1 -like or M2-like phenotype. Thus, future studies are warranted to determine if the currently observed effects translate to human macrophages, to further elucidate the molecular mechanisms governing the current OC-induced alterations, and to determine if in vivo exposure to these compounds either alone or in combination alter macrophage function in the context of both pathogen-induced innate immune responses as well as chronic inflammatory states such as type 2 diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental figure 1: Cellular glutathione levels are not altered by exposure to trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane. J77 macrophages were exposed to trans-nonachlor (A) or oxychlordane (B) for 24 hours then cellular glutathione levels measured in cellular homogenates. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of glutathione (μmole) per μg of cellular homogenate with n=4/group.

Highlights.

Oxychlordane decreased J77 phagocytosis in a concentration-dependent manner.

Trans-nonachlor increased ROS production and pro-inflammatory cytokine production.

Oxychlordane had a biphasic effect on TNFα secretion but did not affect expression.

Both basal and M1-induced Cox-2 expression was decreased by oxychlordane.

5. Acknowledgements

The present study was paid for in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant# 1R21ES030786 to GEH) and by the Office of Research and Graduate Studies at the Mississippi State University College of Veterinary Medicine. Research reported in this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature cited

- Arguin H, Sanchez M, Bray GA, Lovejoy JC, Peters JC, Jandacek RJ, Chaput JP, Tremblay A, 2010. Impact of adopting a vegan diet or an olestra supplementation on plasma organochlorine concentrations: results from two pilot studies. Br J Nutr 103, 1433–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, Castner BJ, Stocking KL, Reddy P, Srinivasan S, Nelson N, Boiani N, Schooley KA, Gerhart M, Davis R, Fitzner JN, Johnson RS, Paxton RJ, March CJ, Cerretti DP, 1997. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature 385, 729–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2019. Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, Updated Tables, In: Services D.o.H.a.H. (Ed.), Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla A, Nguyen KD, Goh YP, 2011. Macrophage-mediated inflammation in metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol 11, 738–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante MC, Mattace Raso G, Esposito E, Bianco G, Iacono A, Clausi MT, Amero P, Santoro A, Simeoli R, Autore G, Meli R, 2011. Effects of non-dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyl congeners (PCB 101, PCB 153 and PCB 180) alone or mixed on J774A.1 macrophage cell line: modification of apoptotic pathway. Toxicol Lett 202, 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannagan RS, Heit B, Heinrichs DE, 2016. Intracellular replication of Staphylococcus aureus in mature phagolysosomes in macrophages precedes host cell death, and bacterial escape and dissemination. Cell Microbiol 18, 514–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannagan RS, Jaumouille V, Grinstein S, 2012. The cell biology of phagocytosis. Annu Rev Pathol 7, 61–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasull M, Castell C, Pallares N, Miret C, Pumarega J, Te Llez-Plaza M, Lopez T, Salas-Salvado J, Lee DH, Goday A, Porta M, 2018. Blood Concentrations of Persistent Organic Pollutants and Unhealthy Metabolic Phenotypes in Normal-Weight, Overweight, and Obese Individuals. Am J Epidemiol 187, 494–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier MS, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Prud’homme D, Karelis AD, Geng D, van Bavel B, Ruzzin J, 2014. The metabolically healthy but obese phenotype is associated with lower plasma levels of persistent organic pollutants as compared to the metabolically abnormal obese phenotype. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 99, E1061–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S, Martinez-Pomares L, 2017. Physiological roles of macrophages. Pflugers Arch 469, 365–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Hara H, Nunez G, 2016. Mechanism and Regulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Trends Biochem Sci 41, 1012–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS, 2006. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444, 860–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS, 2017. Foundations of Immunometabolism and Implications for Metabolic Health and Disease. Immunity 47, 406–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM, 1993. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science 259, 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell G 3rd, Mangum L, 2011. Exposure to bioaccumulative organochlorine compounds alters adipogenesis, fatty acid uptake, and adipokine production in NIH3T3-L1 cells. Toxicol In Vitro 25, 394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell GE 3rd, McDevitt E, Henein L, Mulligan C, Young D, 2018a. Alterations in cellular lipid metabolism produce neutral lipid accumulation following exposure to the organochlorine compound trans-nonachlor in rat primary hepatocytes. Environ Toxicol 33, 962–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell GE 3rd, McDevitt E, Henein L, Mulligan C, Young D, 2018b. “Trans-nonachlor increases extracellular free fatty acid accumulation and de novo lipogenesis to produce hepatic steatosis in McArdle-RH7777 cells”. Toxicol In Vitro 50, 285–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell GE 3rd, Meek E, Kilic J, Mohns M, Mulligan C, Chambers JE, 2014a. Exposure to p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) induces fasting hyperglycemia without insulin resistance in male C57BL/6H mice. Toxicology 320, 6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell GE 3rd, Mulligan C, Meek E, Chambers JE, 2014b. Effect of chronic p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) exposure on high fat diet-induced alterations in glucose and lipid metabolism in male C57BL/6H mice. Toxicology 328C, 112–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MM, Fjaere E, Lock EJ, Naville D, Amlund H, Meugnier E, Le Magueresse Battistoni B, Froyland L, Madsen L, Jessen N, Lund S, Vidal H, Ruzzin J, 2011. Chronic consumption of farmed salmon containing persistent organic pollutants causes insulin resistance and obesity in mice. PloS one 6, e25170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen A, Lyche JL, Polder A, Aaseth J, Skaug MA, 2017. Increased blood levels of persistent organic pollutants (POP) in obese individuals after weight loss-A review. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 20, 22–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzystyniak K, Flipo D, Mansour S, Fournier M, 1989. Suppression of avidin processing and presentation by mouse macrophages after sublethal exposure to dieldrin. Immunopharmacology 18, 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzystyniak K, Trottier B, Jolicoeur P, Fournier M, 1987. Macrophage functional activities versus cellular parameters upon sublethal pesticide exposure in mice. Mol Toxicol 1, 247–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Lee IK, Jin SH, Steffes M, Jacobs DR Jr., 2007a. Association between serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and insulin resistance among nondiabetic adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetes care 30, 622–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Lee IK, Porta M, Steffes M, Jacobs DR Jr., 2007b. Relationship between serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among non-diabetic adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetologia 50, 1841–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Lee IK, Song K, Steffes M, Toscano W, Baker BA, Jacobs DR Jr., 2006. A strong dose-response relation between serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and diabetes: results from the National Health and Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetes care 29, 1638–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR, 2007a. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest 117, 175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng CN, Deyoung SM, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR, 2007b. Increased inflammatory properties of adipose tissue macrophages recruited during diet-induced obesity. Diabetes 56, 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangum LC, Borazjani A, Stokes JV, Matthews AT, Lee JH, Chambers JE, Ross MK, 2015a. Organochlorine insecticides induce NADPH oxidase-dependent reactive oxygen species in human monocytic cells via phospholipase A2/arachidonic acid. Chem Res Toxicol 28, 570–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangum LH, Crow JA, Stokes JV, Howell GE 3rd, Ross MK, Pruett SB, Chambers JE, 2016. Exposure to p,p’-DDE Alters Macrophage Reactivity and Increases Macrophage Numbers in Adipose Stromal Vascular Fraction. Toxicol Sci 150, 169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangum LH, Howell GE 3rd, Chambers JE, 2015b. Exposure to p,p’-DDE enhances differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes in a model of sub-optimal differentiation. Toxicol Lett 238, 65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Sica A, Locati M, 2005. Macrophage polarization comes of age. Immunity 23, 344–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FO, Gordon S, 2014. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep 6, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May P, Bremond P, Sauzet C, Piccerelle P, Grimaldi F, Champion S, Villard PH, 2018. In Vitro Cocktail Effects of PCB-DL (PCB118) and Bulky PCB (PCB153) with BaP on Adipogenesis and on Expression of Genes Involved in the Establishment of a Pro-Inflammatory State. Int J Mol Sci 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro R, Azevedo I, 2010. Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Mediators Inflamm 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss ML, Jin SL, Milla ME, Bickett DM, Burkhart W, Carter HL, Chen WJ, Clay WC, Didsbury JR, Hassler D, Hoffman CR, Kost TA, Lambert MH, Leesnitzer MA, McCauley P, McGeehan G, Mitchell J, Moyer M, Pahel G, Rocque W, Overton LK, Schoenen F, Seaton T, Su JL, Becherer JD, et al. , 1997. Cloning of a disintegrin metalloproteinase that processes precursor tumour-necrosis factor-alpha. Nature 385, 733–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser DM, Edwards JP, 2008. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol 8, 958–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan C, Kondakala S, Yang EJ, Stokes JV, Stewart JA, Kaplan BL, Howell GE 3rd, 2017. Exposure to an environmentally relevant mixture of organochlorine compounds and polychlorinated biphenyls Promotes hepatic steatosis in male Ob/Ob mice. Environ Toxicol 32, 1399–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petriello MC, Brandon JA, Hoffman J, Wang C, Tripathi H, Abdel-Latif A, Ye X, Li X, Yang L, Lee E, Soman S, Barney J, Wahlang B, Hennig B, Morris AJ, 2018. Dioxin-like PCB 126 Increases Systemic Inflammation and Accelerates Atherosclerosis in Lean LDL Receptor-Deficient Mice. Toxicol Sci 162, 548–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rignell-Hydbom A, Rylander L, Hagmar L, 2007. Exposure to persistent organochlorine pollutants and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Human & experimental toxicology 26, 447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzzin J, Petersen R, Meugnier E, Madsen L, Lock EJ, Lillefosse H, Ma T, Pesenti S, Sonne SB, Marstrand TT, Malde MK, Du ZY, Chavey C, Fajas L, Lundebye AK, Brand CL, Vidal H, Kristiansen K, Froyland L, 2009. Persistent Organic Pollutant Exposure Leads to Insulin Resistance Syndrome. Environmental health perspectives. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rylander L, Rignell-Hydbom A, Hagmar L, 2005. A cross-sectional study of the association between persistent organochlorine pollutants and diabetes. Environmental health : a global access science source 4, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro A, Ferrante MC, Di Guida F, Pirozzi C, Lama A, Simeoli R, Clausi MT, Monnolo A, Mollica MP, Mattace Raso G, Meli R, 2015. Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCB 101, 153, and 180) Impair Murine Macrophage Responsiveness to Lipopolysaccharide: Involvement of NF-kappaB Pathway. Toxicol Sci 147, 255–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitarska E, Winnicka A, Klucinski W, 1990. Effect of organochlorine pesticides on the phagocytic activity of bovine milk cells. Zentralbl Veterinarmed A 37, 471–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KW, Novak RF, Anderson HA, Birnbaum LS, Blystone C, Devito M, Jacobs D, Kohrle J, Lee DH, Rylander L, Rignell-Hydbom A, Tornero-Velez R, Turyk ME, Boyles AL, Thayer KA, Lind L, 2013. Evaluation of the association between persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and diabetes in epidemiological studies: a national toxicology program workshop review. Environmental health perspectives 121, 774–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turyk M, Anderson H, Knobeloch L, Imm P, Persky V, 2009a. Organochlorine exposure and incidence of diabetes in a cohort of Great Lakes sport fish consumers. Environmental health perspectives 117, 1076–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turyk M, Anderson HA, Knobeloch L, Imm P, Persky VW, 2009b. Prevalence of diabetes and body burdens of polychlorinated biphenyls, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and p,p’-diphenyldichloroethene in Great Lakes sport fish consumers. Chemosphere 75, 674–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Petriello MC, Zhu B, Hennig B, 2019. PCB 126 induces monocyte/macrophage polarization and inflammation through AhR and NF-kappaB pathways. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 367, 71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr., 2003. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112, 1796–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA, Chen H, 2003. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 112, 1821–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental figure 1: Cellular glutathione levels are not altered by exposure to trans-nonachlor or oxychlordane. J77 macrophages were exposed to trans-nonachlor (A) or oxychlordane (B) for 24 hours then cellular glutathione levels measured in cellular homogenates. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of glutathione (μmole) per μg of cellular homogenate with n=4/group.