Abstract

Frontotemporal dementia is a complex and heterogeneous neurodegenerative disease that encompasses many clinical syndromes, pathological diseases, and genetic mutations. Neuroimaging has played a critical role in our understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of frontotemporal dementia and provided biomarkers to aid diagnosis. Early studies defined patterns of neurodegeneration and hypometabolism associated with the clinical, pathological and genetic aspects of frontotemporal dementia, with more recent studies highlighting how the breakdown of structural and functional brain networks define frontotemporal dementia. Molecular positron emission tomography ligands allowing the in vivo imaging of tau proteins have also provided important insights, although more work is needed to understand the biology of the currently available ligands.

Keywords: semantic, agrammatic, apraxia of speech, tau, TDP-43, progranulin, C9ORF72, MRI, neurodegeneration, connectivity

Introduction

Clinical classification of FTD

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a clinical term for a group of neurodegenerative syndromes which are associated with degeneration of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Clinical diagnostic criteria for FTD published in 1998 recognized three clinical FTD syndromes, termed behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD), semantic dementia (SD) and progressive non-fluent aphasia1. Behavioral variant FTD was characterized by changes in personality and behavioral abnormalities, such as apathy, disinhibition and obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and loss of insight. Patients with bvFTD can develop language abnormalities as the disease progresses, and patients can also develop parkinsonism and features of motor neuron disease (MND). Updated consensus criteria for bvFTD have since been published2. Semantic dementia was characterized by word finding problems (i.e. anomia) and loss of semantic knowledge (such as loss of word, object or face knowledge)3. Lastly, progressive non-fluent aphasia was characterized predominantly by the presence of non-fluent spontaneous speech output. Since this time, it has been recognized that many patients with progressive non-fluent aphasia display combinations of two clinical features: agrammatic aphasia which is characterized by agrammatic written or spoken output and apraxia of speech which is a motor speech disorder affecting the ability to produce words, typically characterized by sound distortions and segmentations4,5. Diagnostic criteria for primary progressive aphasia published in 2011 recognized an agrammatic non-fluent variant of primary progressive aphasia (agPPA) which is defined by the presence of either agrammatism or apraxia of speech6, although the language deficits should be the earliest and dominant feature7. Furthermore, a clinical entity was described in 2012 in which apraxia of speech is the sole presenting symptom, in the absence of agrammatism or any other evidence or aphasia8. This entity was termed primary progressive apraxia of speech (PPAOS)8. Patients with both agPPA and PPAOS often develop an atypical parkinsonian syndrome over time, characterized by limb apraxia, postural instability and eye movement abnormalities9–12. The PPA criteria also defined a semantic variant of PPA which specifically classifies patients with anomia and loss of word knowledge, and hence includes some, although not all, patients that were originally classified as SD6.

Pathological classification of FTD

The pathologies underlying the FTD syndromes are heterogeneous, but are typically defined by the abnormal deposition of one of three proteins: the microtubule-associated protein tau, the TAR DNA binding protein of 43kDa (TDP-43)14, 15 or, less commonly, the tumor associated protein fused in sarcoma (FUS)13. Therefore, the majority of cases can be sub-classified into FTLD-tau, FTLD-TDP and FTLD-FUS (Figure 1), based on the biochemical signature of the abnormally deposited protein14,15. Each of these three groups is also sub-classified based on inclusion morphology and lesion distribution. Hence, FTLD-tau includes specific pathologies such as Pick’s disease16, progressive supranuclear palsy17 and corticobasal degeneration18,19; FTLD-TDP includes four different types (A-D) 20–22, and FTLD-FUS includes the specific pathologies of neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease23,24, basophilic inclusion body disease25,26 and atypical FTLD with ubiquitin-only immunoreactive changes27,28. The syndrome of bvFTD can be associated with many different FTLD pathologies, and can result from FTLD-tau, FTLD-TDP or FTLD-FUS pathology (Figure 1)15. There may be some clinical signs that suggest one specific pathology over another, although generally it is very different to predict the underlying pathology in bvFTD. The syndrome of SD has a more homogeneous pathology and typically results from FTLD-TDP pathology (Figure 1), particularly FTLD-TDP type C15. The syndrome PPAOS also has a relatively homogeneous pathology, with most cases resulting from FTLD-tau (Figure 1) characterized by deposition of 4-repeat tau, i.e. progressive supranuclear palsy or corticobasal degeneration10. In fact, the presence of apraxia of speech has been shown to be predictive of an underlying FTLD-tau pathology, even when it co-occurs with agrammatic aphasia10. Hence, patients with agPPA, that often have co-occurring apraxia of speech, also often have an underlying FTLD-tau pathology10,29. Cases of aPPA have been reported with FTLD-TDP, although this pathology is rarer than FTLD-tau in these patients29. Furthermore, patients with the clinical syndromes of FTD have been reported to have the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease which is characterized by deposition of 3R+4R tau and beta-amyloid30.

Figure 1: Schematic illustrating the relationship between FTD clinical syndrome and pathological diagnosis.

BvFTD = behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, SD = semantic dementia; agPPA = agrammatic variant of primary progressive aphasia; PPAOS = primary progressive aphasia

Neuroimaging in FTD

Neuroimaging research has been critical in increasing our understanding of FTD. Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and (18F)-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) studies have characterized patterns of neurodegeneration and hypometabolism that define the different clinical and pathological variants of FTD, while diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and resting-state fMRI have improved our understanding of the structural and functional connectivity breakdowns associated with FTD. The recent availability of molecular PET ligands that bind to beta-amyloid or tau proteins has also allowed the in vivo investigation of brain pathology. The knowledge we have gained from these neuroimaging modalities concerning the pathophysiology of FTD will be discussed in this review.

Imaging in the clinical syndromes of FTD

Behavioral variant FTD

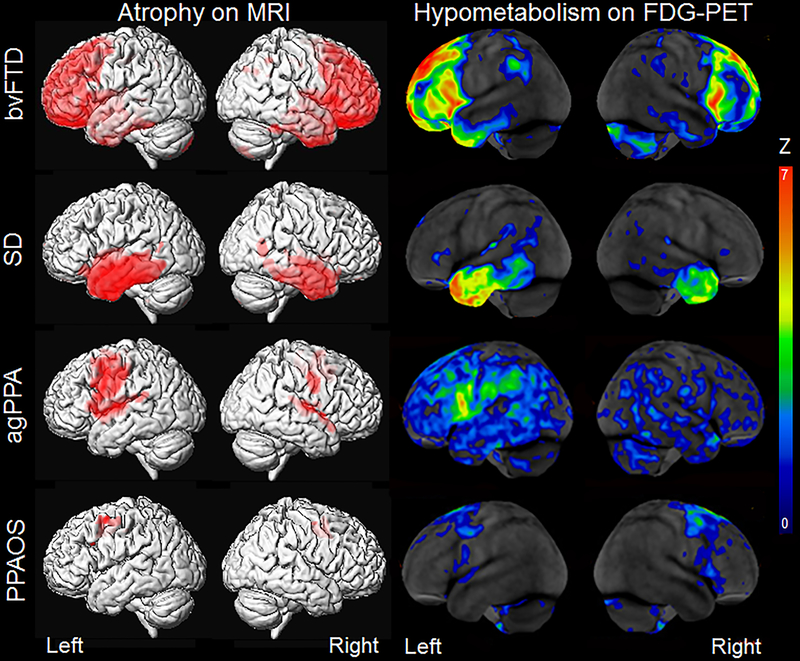

Behavioral variant FTD is typically associated with atrophy on structural MRI and hypometabolism on FDG-PET in the prefrontal cortex and anterior temporal lobes, with relative sparing of more posterior regions of the brain, such as the occipital lobe31–39 (Figure 2). Regions in the frontal lobe that are commonly affected in bvFTD include the orbitofrontal cortex, medial and lateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate, along with atrophy of the adjacent insula cortex. Imaging studies have demonstrated that atrophy of these frontal and anterior temporal regions is related to the behavioral symptoms observed in bvFTD, including apathy, disinhibition, loss of empathy, and aggression40–50. Atrophy of subcortical structures, such as caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, thalamus and nucleus accumbens, are also observed, reflecting dysfunction of cortico-striato-thalamic circuits51 which have also been associated with behavioral abnormalities in bvFTD52–61. Neurodegeneration in bvFTD is progressive, with decline in brain volume observed over time. Rates of whole brain volume loss can be as fast as 3% per year34, 35, with greatest rates of decline observed in the frontal lobes62–68. Frontotemporal and subcortical atrophy is observed in the mildest stages of the disease69 and even before patients meet criteria for bvFTD70, and is observed to spread as the disease progresses69.

Figure 2: Patterns of atrophy and hypometabolism associated with the FTD clinical syndromes.

Group-level maps depicting grey matter atrophy compared to controls are shown on three dimensional renders of the brain. Hypometabolism on FDG-PET is shown for individual patients, represented as Z score maps depicting abnormalities compared to controls.

However, a great deal of heterogeneity in patterns of neurodegeneration has been observed within cohorts of bvFTD patients on both MRI and FDG-PET71–75. Some patients tend to have more predominant frontal abnormalities71,72,75, others have predominant temporal abnormalities71,72,75, and some show involvement of temporal and parietal structures71,73,75. A predominantly subcortical subtype has also been identified71,72. Importantly, clinical characteristics differ across these different anatomical phenotypes, with the frontal phenotype showing worse executive performance and the temporal phenotype showing worse episodic memory impairment73,75. Furthermore, the patients with frontal dominant patterns of atrophy tend to show faster clinical decline76, while the subcortical subtype shows relatively slow disease progression71. Recognizing the different phenotypes of bvFTD could, therefore, be important to help improve prognostic estimates for patients. The phenotypes did not differ in terms of behavioral abnormalities, reflecting the fact that behavioral abnormalities are the key features of a bvFTD diagnosis. Heterogeneity is also observed in the degree of asymmetry in brain atrophy42,73 with most patients showing symmetric patterns of atrophy, although patients also show right and left-sided patterns of atrophy42. In addition, some bvFTD patients have been reported that showed very little atrophy on MRI, despite fulfilling clinical criteria for bvFTD, and show slow rates of clinical decline77–79. Some of these patients have been shown to display FTD pathology80 and are occasionally associated with the presence of a C9ORF72 genetic mutation79 (see genetic FTD section). Those patients with additional MND, i.e. FTD-MND, show shorter disease duration than typical bvFTD patients and have been shown to have very similar patterns of atrophy to bvFTD, particularly with involvement of the frontal lobes81–83. The degree of atrophy is however typically less that that observed in patients with bvFTD81,83, although these patients show greater involvement of the frontal and temporal lobes compared to patients with MND in the absence of FTD83.

Structural MRI and FDG-PET findings have been shown to be diagnostically useful in differentiating bvFTD from healthy individuals and patients with other neurodegenerative diseases. In particular, the relative pattern of involvement of anterior brain structures nicely differentiates patients with bvFTD from those with typical Alzheimer’s dementia which typically targets posterior regions of the brain, including the posterior temporal and parietal lobes84. Studies that have utilized pattern classification techniques have found that structural MRI can differentiate bvFTD from controls with an accuracy of 85%85,86, and differentiate bvFTD from Alzheimer’s dementia with an accuracy of 82%86. Diagnostic accuracy has also been shown to be excellent with pattern analysis of FDG-PET, with discriminatory power of 92.2% to differentiate bvFTD from Alzheimer’s dementia and 87.6% to differentiate bvFTD from the other language variants of FTD87. In fact, simple visual assessments of FDG-PET looking for frontal, anterior cingulate and anterior temporal hypometabolism have excellent specificity (97.6%) and sensitivity (86%) in differentiating bvFTD from Alzheimer’s dementia, and can improve differentiation based on clinical features alone88. There is also evidence that FDG-PET can improve diagnosis over structural MRI89–91, with FDG-PET being more sensitive to underlying dysfunction than structural MRI which can be normal at baseline in bvFTD patients92.

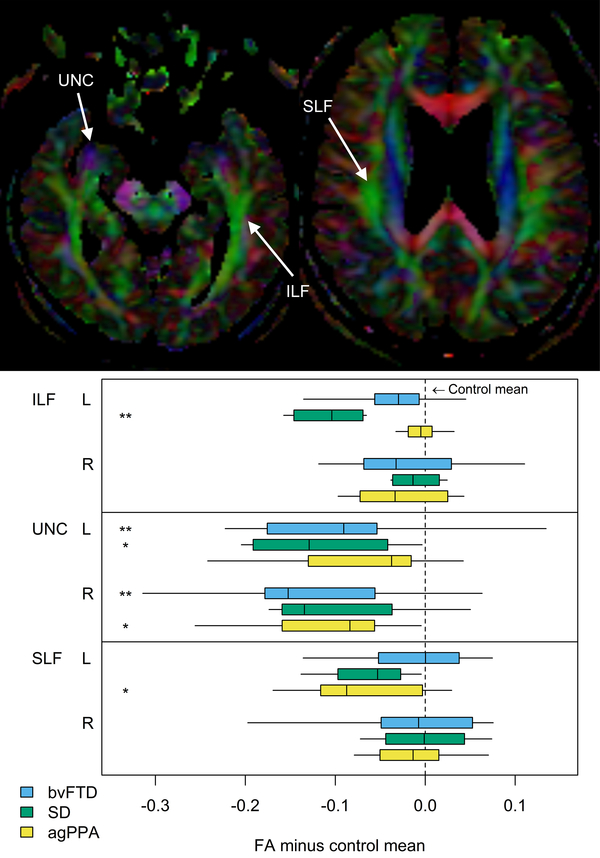

Disruption in the structural connectivity of the brain, measured using DTI, is also a feature of bvFTD. Degeneration is observed in white matter tracts that have reciprocal projections into the frontal and temporal lobes, such as the superior longitudinal fasciculus, anterior cingulum, genu of the corpus callosum, uncinate fasciculus and the inferior longitudinal fasciculus45,93–98 (Figure 3). Degeneration of these tracts is associated with behavioral severity in bvFTD45,96. Degeneration is also observed in fronto-striatal and fronto-thalamic pathways51. Less severe degeneration is also observed in tracts that connect into posterior regions of the brain, including the posterior cingulate and posterior aspects of the superior longitudinal fasciculus. Longitudinal studies have observed progressive degeneration of the same set of tracts that show abnormalities in cross-sectional studies, particularly the uncinate fasciculus, genu of the corpus callosum, paracallosal cingulum and frontal white matter99–101, with additional progression to involve more posterior white matter tracts located in the posterior temporal and occipital lobe102. This demonstrates a spreading of disease from anterior to more posterior brain regions. DTI measures from the anterior corpus callosum are particularly promising in bvFTD since they provide good differentiation of bvFTD patients from other clinical variants of FTD93,95, perform well as a longitudinal marker to differentiate bvFTD from controls100, and are associated with longitudinal decline in executive function in bvFTD103. There is also a suggestion that DTI can pick up abnormalities in patients in which the MRI and FDG-PET scans are normal104 and DTI findings can show more widespread findings than structural MRI98,105, suggesting good sensitivity of DTI. The value of DTI compared to other modalities is less clear. A couple of studies have found that DTI performed better than regional volumes in differentiating bvFTD from controls106 or from other FTD syndromes107, although another found that DTI measures do not perform as well as FDG-PET for diagnosis at the individual-patient level104. DTI does, however, appear to add complementary information to structural MRI when differentiating bvFTD from controls and Alzheimer’s dementia, and hence a combination of markers from different modalities may be the best approach to differential diagnosis108.

Figure 3: Diffusion tensor imaging findings in bvFTD, SD and agPPA.

The top panel shows color coded fractional anisotropy (FA) maps showing major white matter tracts. The bottom panel shows box-plots of FA values across the three clinical groups. The left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF) is preferentially affected in SD, the uncinate fasciculus (UNC) is affected in both bvFTD and SD, and the left superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) is preferentially affected in agPPA. SD = semantic dementia; bvFTD = behavioral variant of FTD; agPPA = agrammatic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Reproduced with permission from Imaging in Neurodegenerative Disorders (Oxford University Press, 2015, edited by Luca Saba)

Functional brain connectivity in bvFTD has also been assessed using resting-state fMRI analyses. Studies that have focused on assessing specific brain networks have shown that one of the characteristic changes observed in bvFTD is decreased functional connectivity within the salience network109–114. The salience network is involved in processing socially relevant information and involves anterior cingulate and fronto-insular regions. Similarly, other studies have found bilateral disconnection between frontal and limbic regions of the brain114–116. Disruptions in connectivity in frontolimbic regions appears to be central to the disease process in bvFTD and has been shown to correlate to the degree of behavioral and executive impairment observed in bvFTD111,116–118. Connectivity from the frontal lobe also appears to decrease with disease progression in bvFTD119. However, decreased connectivity has also been observed in the basal ganglia115, insula115 and dorsal attention network114, and disconnection between the frontal lobes and posterior regions of the brain, including occipital lobe115,120,121, also appear to occur in bvFTD. Increases in connectivity have also been observed in other networks, such as the medial parietal components of the default mode network109–112 and attention/working memory network114, with posterior hubs relatively preserved in bvFTD120. This pattern of connectivity changes may be useful to differentiate bvFTD patients from patients with Alzheimer’s dementia, which typically show reduced connectivity in the default mode network and posterior brain nodes110,114,122. Studies have started to analyze and compare resting state fMRI to other neuroimaging metrics in terms of diagnostic utility. In one study, optimum differentiation of bvFTD and controls was obtained with a combination of structural MRI, DTI and resting state measures123. Similarly, optimum differentiation of bvFTD and Alzheimer’s dementia was obtained with a combination of DTI and resting state fMRI measures123 - combining functional and structural measures improved differentiation

Tau PET imaging has been assessed in patients with bvFTD, particularly using the THK-5351 and 18F-flortaucipir ligands. These studies have typically observed elevated uptake in the white matter of the frontal lobe124–127, as well as anterior cingulate, temporal lobe, insula, and striatum125,127 in bvFTD patients compared to controls (Figure 4). However, results across bvFTD patients are variable, with only 50% of sporadic bvFTD patients in one study demonstrating elevated 18F-flortaucipir uptake compared to controls126. Consistent with structural MRI, the patterns of uptake in bvFTD differ from the more temporoparietal and occipital patterns of uptake observed in Alzheimer’s dementia124. One study found that frontal white matter uptake using THK-5351 was higher in bvFTD compared to Alzheimer’s dementia, although in another study the degree of 18F-flortaucipir uptake in bvFTD was less than the binding range typically seen in Alzheimer’s dementia126. However, it is very difficult to interpret tau PET findings in bvFTD given the pathological heterogeneity and the fact that a large proportion of cases will likely have an underlying TDP-43 proteinopathy rather than a tauopathy. It is currently unclear what the ligands are binding to in the white matter and basal ganglia and whether it reflects off-target binding to a non-tau target128. Furthermore, the tau isoforms present in bvFTD patients with genetic mutations can vary and hence influence tau-PET findings (see pathological section below) and many of these bvFTD studies have not screened cases for genetic mutations124,125,127. In addition, approximately 50% of bvFTD cases can show amyloid deposition on PET scanning129 suggesting the possibility of underlying AD pathology which may influence tau-PET findings in bvFTD126. The value of tau-PET in bvFTD is therefore currently low until we have a better understand of the biological underpinnings of ligand binding.

Figure 4: 18F-flortaucipir images from patients with different FTD clinical syndromes.

Mild uptake predominantly in the white matter is observed in the frontotemporal lobes in the bvFTD patient, left temporal lobe in the SD patient, left frontal lobe of the agPPA patient and bilateral premotor cortex of the PPAOS patient.

Semantic dementia

Semantic dementia is associated with characteristic patterns of atrophy on structural MRI and hypometabolism on FDG-PET affecting the temporal lobes74, 107–110. An anteroposterior gradient of atrophy is typically observed, with most marked atrophy observed in anterior temporal regions (Figure 2). Degeneration is particularly severe in the fusiform and inferior temporal gyri, although also severely affects the hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, and middle temporal gyrus130–132. The orbitofrontal cortex, medial frontal lobes, striatum and anterior insula can also be involved32,58,132. Asymmetry is also a characteristic feature of SD. Patients which present with anomia and loss of word knowledge (and hence fulfill criteria for the semantic variant of PPA) typically show left-predominant patterns of atrophy and hypometabolism32,130–132. However, other patients can show right-predominant patterns of atrophy and may have deficits in other types of semantic knowledge ( such as recognizing familiar faces133, facial emotions134or musical tunes135,136) and behavioral abnormalities137–140. Whilst the disease typically affects one hemisphere of the anterior temporal lobes early in the disease, atrophy tends to spread within both temporal lobes62,63,141–144 until patterns are often more symmetrical138 and the frontal lobes become increasingly involved145. The majority of studies assessing neuroimaging features of SD focus on the more common left-sided variant of SD.

The distinctive anterior temporal pattern of atrophy and hypometabolism in SD can be diagnostically useful to differentiate SD from other neurodegenerative diseases. Although anteromedial temporal structures can be involved in both SD and Alzheimer’s dementia146,147, the anteroposterior gradient of temporal atrophy is not observed in Alzheimer’s dementia130. One study found that an anteroposterior gradient of hypoperfusion on SPECT can help differentiate patients with SD from those with Alzheimer’s dementia148. Rates of atrophy of the temporal lobes are also faster in SD compared to Alzheimer’s dementia63. The patterns of neurodegeneration in SD can overlap with those seen in bvFTD. However, the frontal lobe is usually affected to a greater degree in bvFTD65, and a ratio of temporal to frontal atrophy may be useful to distinguish these syndromes62. In addition, the temporal pole is more atrophic in SD compared to bvFTD, with left temporal pole volume separating svPPA from bvFTD with 82% sensitivity and 80% specificity in one study72. Utilizing both FDG-PET and MRI measures of the temporal pole may in fact improve classification of SD from Alzheimer’s dementia and other FTD syndromes better than either modality assessed in isolation149.

Consistent with the temporal lobe focus of neurodegeneration, SD also shows reduced structural connectivity within the temporal lobes150. White matter tract degeneration is observed in tracts that project from the temporal lobes, including the uncinate fasciculus and the inferior longitudinal fasciculus, particularly in the left hemisphere94,95,107,147,151–155 (Figure 3). Degeneration is also observed in frontal lobe white matter tracts, including the genu of the corpus callosum and the arcuate fasciculus, and posterior temporal lobe, although there is usually a relative sparing of tracts in parietal regions of the brain94,152,154. While initial white matter degeneration in SD is limited to left temporal lobe tracts, there is evidence that degeneration spreads to bilateral frontotemporal tracts with disease progression102. Compared to bvFTD, SD patients show greater degeneration of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus93,94, uncinate fasciculus156 and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus156, and less degeneration of the genu of the corpus callosum, frontal white matter and parietal regions of the superior longitudinal fasciculus105,107. In one study, bvFTD also tended to show greater involvement of tracts in the right hemisphere, while SD showed greater involvement of tracts in the left hemisphere156. Semantic dementia appears to involve different white matter projections from the medial temporal lobe compared to Alzheimer’s dementia, with SD targeting the uncinate and inferior longitudinal fasciculus and Alzheimer’s dementia targeting the cingulum and corpus callosum, demonstrating vulnerability of distinct networks that both involve the medial temporal lobe147 – perhaps explaining the difference clinical presentations despite…

Resting state fMRI studies have shown similarities in how neural networks are disrupted in SD compared to bvFTD, with disruptions in the salience network and frontolimbic connectivity also observed in SD patients111,116. These similarities may reflect the fact that similar behavioral abnormalities can be observed in both SD and bvFTD patients116. However, SD appears to be specifically associated with reduced local and distinct connectivity from the anterior temporal lobe. Reduced connectivity has been observed between the left anterior temporal lobe and bilateral frontal and cingulate regions in SD compared to controls and bvFTD156. In addition, SD patients show a loss of highly connected hubs in the left inferior temporal lobe, as well as in the orbitofrontal cortex and occipital lobes157. These patterns of reduced functional connectivity concur with structural connectivity studies that have shown degeneration of tracts that connect the temporal pole, orbitofrontal cortex and occipital cortex, such as the uncinate fasciculus, inferior longitudinal fasciculus and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus. The damage of these tracts could be responsible for the functional disconnections between these regions in SD. There is also evidence linking atrophy in SD to disrupted connectivity with the anterior temporal lobe, suggesting that atrophy may follow these connectional pathways158.

Recent molecular PET imaging studies have produced some interesting findings in SD. Firstly, amyloid PET studies have shown that a high proportion, in fact up to 30%, of SD patients can have beta-amyloid deposition in their brains159–163. The presence of beta-amyloid deposition does not appear to influence the clinical presentation of SD, although the patients with beta-amyloid tend to be older163. Although Alzheimer’s disease can be the pathological cause of SD in some cases29,164–166, this is relatively rare. Hence, the PET findings may reflect age associated beta-amyloid deposition in SD patients where the primary pathology is still a TDP-43 proteinopathy. Second, tau-PET imaging has been performed in patients with SD and, somewhat surprisingly given the underlying pathology, elevated uptake is observed in these patients (Figure 4). Elevated uptake has been demonstrated in the anteromedial temporal lobe, as well as regions in the basal frontal lobes, insula and putamen, with elevated uptake typically observed in the white matter rather than the grey matter 126,163,167–170. It remains unclear what the ligand is binding to in these cases. It could reflect off-target binding, reflect low levels of binding to TDP-43 or may be binding to low levels of tau that coexists with TDP-43167–169. Tau PET uptake is, in fact, higher in SD patients that show beta-amyloid deposition compared to those without beta-amyloid deposition, perhaps supporting the hypothesis that the ligand may be binding to some tau pathology present in the brain in the beta-amyloid positive patients163. Uptake remains elevated in the patients without beta-amyloid deposition, however, suggesting a potential alternative explanation for binding in these patients163,170.

Agrammatic primary progressive aphasia and primary progressive apraxia of speech

The agPPA (referred to as progressive non-fluent aphasia in many studies) is associated with relatively focal patterns of atrophy on MRI and hypometabolism on FDG-PET that target the left posterior frontal lobe, including inferior (Broca’s area), middle and superior premotor gyri10,155,171–177, which is accompanied by widening of the left perisylvian fissure (Figure 2). Atrophy and hypometabolism can also be observed in the insula, striatum, superior temporal lobe, and other regions in the left frontal and parietal lobes172,173. In contrast to bvFTD and SD, the anterior temporal lobes are typically relatively spared in patients with agPPA. Patients diagnosed with agPPA will most commonly have some combination of agrammatic aphasia and apraxia of speech, and it has been shown that these two clinical features have distinct anatomical correlates178. Apraxia of speech is associated with atrophy and hypometabolism in the superior premotor cortex8,75, while agrammatic aphasia is associated with abnormalities in the left inferior frontal lobe178–180 and other temporal and parietal regions178 within the language network181. In fact, patients with PPAOS, which only have apraxia of speech in the absence of aphasia, show very focal patterns of atrophy and hypometabolism involving the bilateral supplementary motor area and lateral superior premotor cortex8,182 (Figure 2), and show less involvement of the left inferior frontal lobe and lateral temporal lobe compared to agPPA182. As with the other FTD syndromes, atrophy and hypometabolism are progressive in both agPPA and PPAOS. In agPPA, the fastest rates of atrophy are typically observed in the frontal lobes143,144,183,184, with progressive volume loss also observed in the motor cortex, temporal and parietal lobes, insula, basal ganglia, and brainstem11,144,184,185. Atrophy progresses in the right hemisphere in addition to the left, although left-sided asymmetry is typically maintained over time144,185. In PPAOS, bilateral patterns of progressive volume loss over time are observed in the premotor cortex, motor cortex, basal ganglia and midbrain9. There is, therefore, overlap in the longitudinal patterns of atrophy observed in agPPA and PPAOS, reflecting progression of common clinical features. Degeneration of the motor cortex and brainstem, for example, are associated with the development and progression of parkinsonism and limb apraxia in these patients11. However, agPPA showed faster rates of atrophy in the inferior frontal lobe compared to PPAOS, reflecting greater decline in agrammatism than the PPAOS patients11. Agrammatism can develop over time in some PPAOS patients, although not all, and when it does develop it is associated with atrophy of the left inferior frontal lobe, thalamus and putamen, showing that a network of regions is responsible for the development of agrammatic aphasia186.

White matter tract degeneration is associated with both agPPA and PPAOS. In agPPA, degeneration has been observed in frontotemporal and frontoparietal connections of the left superior longitudinal fasciculus94,154,182,187–189 (Figure 3), particularly involving the arcuate fasciculus that projects into the inferior frontal lobe107. The aslant tract that projects from Broca’s area to the anterior cingulate and supplementary motor cortex is also affected190,191. However, degeneration is also observed in other frontal tracts, including the body of the corpus callosum, anterior cingulate, inferior frontal-occipital fasciculus, and frontostriatal pathways107,154,182,188,192. White matter tract findings are typically asymmetric, with greater involvement of the left hemisphere, although tend to be more bilateral and widespead than patterns of atrophy. Degeneration in this network of white matter tracts is associated with the language deficits observed in agPPA188,189,192. Temporal lobe white matter tracts can be affected94,153,188,193 although this is not a consistent finding187, and these tracts show greater involvement in SD and bvFTD compared to agPPA94,153,187. Generally there is little overlap in patterns of tract degeneration between agPPA and SD193. The superior longitudinal fasciculus has been shown to be involved to a greater degree in agPPA compared to bvFTD94. Patients with PPAOS show less widespread patterns of white matter tract degeneration than agPPA, with bilateral involvement of the body of the corpus callosum and premotor aspects of the superior longitudinal fasciculus that lie adjacent to regions of grey matter loss in these patients8,182 (Figure 5). In fact, it appears as though apraxia of speech severity is particularly associated with degeneration of white matter tracts connecting the supplementary motor area to the inferior frontal cortex, premotor cortex and striatum192. White matter tract degeneration worsens over time in agPPA11,100,102, with widespread bilateral longitudinal degeneration observed in the superior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior and superior fronto-occipital fasciculus, cingulum, corticospinal tracts and white matter underlying motor cortex11. Longitudinal patterns of white matter tract degeneration are more focal in PPAOS, showing progression in the superior longitudinal fasciculus and body of the corpus callosum and spread to involve the splenium of the corpus callosum and white matter underlying the motor cortex9,11. It, therefore, appears that even with disease progression PPAOS remains a more focal disease compared to agPPA, although overlap between the two syndromes is observed.

Figure 5: Diffusion tensor imaging abnormalities in PPAOS.

Regions of reduced tract integrity are shown in red on top of a green white matter skeleton of the brain. Results were created using track-based spatial statistics comparing a PPAOS cohort to controls.

Consistent with the anatomical findings, disrupted functional connectivity in agPPA has been shown to be asymmetric, predominantly affecting the left hemisphere115. Widespread disruptions in connectivity have been observed throughout frontal, temporal and striatal regions in the left hemisphere115. Within the speech-language network, agPPA patients have been shown to have a loss of functional hubs in the left fronto-temporal-parietal area and new nodes in more anterior frontal regions and the right frontal lobe compared to controls194, suggesting a reorganization of the speech-language network is occurring in agPPA. In fact, longitudinal progression of atrophy in agPPA has been shown to be spatially related to functional connectivity of the speech-language network, supporting the view that neurodegeneration in agPPA spreads through this network191. Patients with PPAOS also show disruption of the speech-language network, with disrupted connectivity of the right supplementary motor area and left posterior temporal gyrus to the rest of the speech-language network195. The connectivity of the right supplementary motor area correlated with the severity of apraxia of speech195. These results fit with MRI/FDG-PET and structural connectivity findings and point towards an important role of the supplementary motor area in apraxia of speech.

Molecular PET imaging using beta-amyloid and tau ligands have been assessed in agPPA and PPAOS patients. Beta-amyloid deposition on PET has been observed in 0–30% of agPPA patients162,196–198 and 8% of PPAOS patients8, although the MRI signatures do not seem to differ according to beta-amyloid status199. Elevated 18F-flortaucipir uptake has been observed in both agPPA and PPAOS (Figure 4). Mildly increased uptake has been observed in frontal white matter and subcortical grey matter structures, incluidng thalamus and basal ganglia, in agPPA, with greater uptake observed in the left hemisphere126,168,170. Patterns within agPPA appear to differ depending on the presence of apraxia of speech, with those with apraxia of speech showing greater uptake in the motor cortex200. The patterns of tau PET uptake in agPPA differ from those in SD and accounting for frontal versus temporal uptake allows good seperation of these two diseases168. Mild tau-PET uptake, predominantly in the white matter, is also observed in PPAOS, with uptake observed in the supplementary motor area and motor cortex201. Elevated uptake in the inferior frontal gyrus was also observed in PPAOS patients that develop agramamtic aphasia201. Patterns of tau-PET uptake, therefore, match closely with patterns of neurodegeneration observed in both agPPA and PPAOS. Given that agPPA and PPAOS most commonly result from a 4R tauopathy, it is possible that the ligands are detecting the presence of underlying tau proteins. However, autoradiographic studies have not observed good binding of 18F-flortaucipir to 4R tau isoforms128,202–204, casting doubt on the biological interpretation of findings in these diseases. It is also currently unclear why the tau-PET findings are located predominantly in the white matter in the agPPA and PPAOS, and more work is needed to understand the mechanisms of binding in these cases.

Imaging predicting pathology in FTD

The different pathologies that underlie the FTD syndromes have been shown to be associated with different neuroimaging signatures which can be helpful in allowing the prediction of underlying pathology in FTD. Since future therapeutics will likely target specific proteins or pathologies it will be necessary to provide a pathological diagnosis, rather than just a syndromic diagnosis, for FTD patients. This is particularly important in syndromes where the underlying pathology can be heterogeneous, such as bvFTD and agPPA.

There does not appear to be specific neuroimaging signatures of FTLD-tau or FTLD-TDP, but rather signatures of the specific pathologies within each of these proteinopathies205–208. Within the FTLD-tau diseases, Pick’s disease has a very different neuroimaging signature compared to PSP and CBD. Pick’s disease has a characteristic pattern of knife-edge atrophy of the prefrontal cortex, with additional involvement of the anterior temporal lobes, insula and anterior cingulate209–212 (Figure 6). The cortex appears knife-edge due to the dramatic degree of shrinkage of the frontal gyri. In contrast, PSP and CBD involve more posterior regions of the frontal lobe, including premotor cortex59 (Figure 6). Cortical atrophy is typically more widespread in CBD compared to PSP, spreading posteriorly to involve the parietal lobe, and with greater involvement of the basal ganglia213,214. Rates of brain atrophy are also typically faster in CBD compared to PSP215. Midbrain atrophy is typically considered a diagnostic feature of PSP, although the presence of midbrain atrophy is associated with the clinical syndrome of PSP, rather than the presence of pathological PSP216. Hence, midbrain atrophy can be observed in patients that develop the typical clinical features of PSP (postural instability and vertical supranuclear gaze palsy) but have CBD pathology216. Cortical atrophy is often asymmetric in CBD, relating to asymmetry that is present clinically, although symmetric CBD cases are also observed217,218 and asymmetric cases do not always have CBD pathology219,220. Different patterns of atrophy are also observed across the FTLD-TDP types. Type A is associated with widespread and asymmetric atrophy of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes (Figure 6); type B is associated with atrophy of the frontal and medial temporal lobes; and type C is associated with asymmetric atrophy of the anteromedial temporal lobes and nearly always presents clinically with SD221,222. The FTLD-FUS diseases are rarer than FTLD-tau or FTLD-TDP and are associated with frontotemporal atrophy but with additional and severe atrophy of the caudate223–225. The caudate has been shown to be involved to a greater degree in FTLD-FUS compared to other FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP diseases223. This caudate signature has been observed across different FTLD-FUS diseases and hence may be a useful biomarker of FTLD-FUS.

Figure 6: Individual MRI scans from patients with bvFTD but different pathological diagnoses.

The patient with Pick’s disease shows knife-edge atrophy of the frontal lobes. The patient with FTLD-TDP shows widespread frontal, temporal and parietal atrophy. The patient with corticobasal degeneration shows atrophy predominantly of the posterior frontal lobes.

Studies have demonstrated that these different FTD pathologies do show different neuroimaging features within groups of patients with the same clinical syndrome. Within patients with bvFTD, patterns of grey matter atrophy differ across the pathologies of Pick’s disease, CBD and FTLD-TDP type A (Figure 6). While all three pathologies showed atrophy of the frontal lobes, likely related to the common clinical presentation, there are differences that may be diagnostically useful. Pick’s disease has been shown to have greater atrophy in the anterior frontal lobes, insula and temporal pole compared to CBD226, while CBD has greater atrophy in the parietal lobe compared to Pick’s disease226. Furthermore, FTLD-TDP type has been shown to have greater atrophy in the parietal lobe and posterior temporal lobe compared to both CBD and Pick’s disease212. Generally, CBD showed milder patterns of atrophy compared to both Pick’s disease226 and FTLD-TDP type A212. Imaging has also been shown to be useful in determining the underlying pathology in patients with agPPA. The agPPA patients with CBD pathology showed more widespread grey matter atrophy compared to those with PSP pathology, involving frontal, premotor and motor cortices, insula and striatum, and greater white matter atrophy in anterior parts of the frontal lobe227. However, the agPPA patients with PSP pathology developed greater atrophy of the midbrain and pons compared to those with CBD227. Furthermore, agPPA patients with FTLD-TDP pathology appear to show less white matter atrophy than agPPA patients with either PSP or CBD pathology228. Neuroimaging, therefore, shows promise to be able to aid in the prediction of specific pathologies within bvFTD and agPPA.

Imaging in genetic FTD

A relatively large proportion of FTD patients have a family history and an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. A number of mutations have now been identified that account for many of these families. The most common mutations occur in the microtubule associated protein tau (MAPT) 229 and progranulin (GRN)230,231 genes, along with an expansion of a noncoding GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in the C9ORF72 gene that is genetically linked to chromosome 9p232,233. Pathologically, both the GRN and C9ORF72 expansion gene mutations are associated with FTLD-TDP, while MAPT mutations form another genetic variant of FTLD-tau. All three mutations are most commonly associated with bvFTD, although more varied clinical presentations are associated with GRN mutations, including agPPA234–238, and C9ORF72 repeat expansions are also associated with FTD-MND232,233. Neuroimaging has proven incredibly valuable in genetic FTD to define the abnormalities associated with each mutation. This has improved our understanding of heterogeneity in FTD and provided markers that might predict the presence of a genetic mutation. Furthermore, asymptomatic family members with a genetic mutation can be followed before the development of symptoms allowing us to determine the earliest neuroimaging abnormalities in FTD; knowledge that will be crucial to allow early diagnosis.

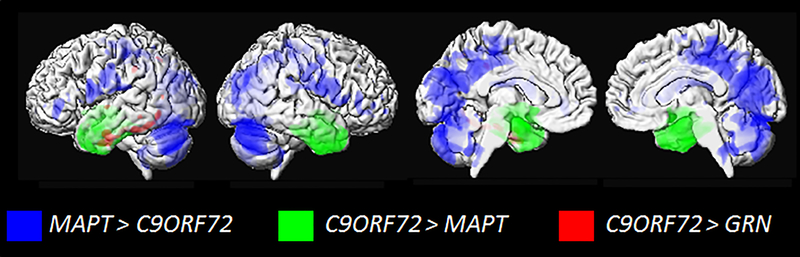

The three main genetic mutations have been shown to have distinct neuroanatomical correlates on structural MRI. The MAPT mutations target the anteromedial temporal lobes, with additional atrophy observed in the frontal lobes, particularly the orbitofrontal cortex210,239. Imaging findings are relatively consistent across different mutations, although some mutations tend to show predominant involvement of the medial temporal lobes and others the lateral temporal lobe240. The GRN mutations can show more variable patterns of atrophy and hypometabolism at the patient level, although they tend to typically show quite widespread and asymmetric involvement236,241 of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes241,242. Involvement of the parietal lobe is particularly characteristic of GRN mutations 234,241,243. The C9ORF72 repeat expansion has been shown to be associated with symmetric patterns of atrophy involving the frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobes, in addition to the cerebellum244–247 and thalamus245–247. There is evidence that imaging can help differentiate across the three mutations. Studies have found that patients with GRN mutations show more asymmetry245 and greater involvement of the posterior regions of the brain compared to MAPT and C9ORF72 carriers234,240,244, while MAPT carriers showed greater atrophy of the anterior temporal lobes than both GRN and C9ORF72 carriers240,244,245 (Figure 7). Furthermore, the C9ORF72 repeat expansions showing greater atrophy in parietal and occipital lobes compared to MAPT carriers and sporadic bvFTD244 (Figure 7). There is some disagreement in the field with the diagnostic utility of the thalamus for detecting C9ORF72 mutations, with some showing the thalamus differentiates C9ORF72 patients from sporadic FTD248, while others finding that the thalamus does not help to differentiate between the different FTD mutations244,249. Differences across FTD mutations have also been identified in longitudinal rates of progression, with GRN carriers showing faster rates of atrophy across the brain than both MAPT250,251 and C9ORF72245,252, as well as sporadic FTD252. The GRN mutation, therefore, appears to be particularly aggressive.

Figure 7: Three dimensional renders highlighting regional differences in patterns of atrophy amongst FTD genetic mutations.

Blue shows regions with greater atrophy in C9ORF72 compared to MAPT; green shows regions with greater atrophy in MAPT compared to C9ORF72; and red shows regions with greater atrophy in GRN compared to C9ORF72

Studies that have assessed asymptomatic mutation carriers have found that grey matter atrophy can be detected before symptom onset in all three mutations, with regional findings typically matching those observed in symptomatic patients but to a lesser degree253–258. Alterations in structural and functional connectivity have also been observed before the onset of clinical symptoms in genetic FTD255,259. Degeneration of the uncinate fasciculus has been observed both in symptomatic and asymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers98,256,260; degeneration of white matter tracts projecting into the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes, such as uncinate fasciculus, anterior corpus callosum, fronto-occipital fasciculus and superior longitudinal fasciculus have been observed in asymptomatic GRN mutation carriers255,261; and, similarly, degeneration of white matter tracts that project into frontal and posterior brain regions, including the anterior thalamic radiations, have been observed in symptomatic and asymptomatic C9ORF7298,245,254,257,260. In fact, one study found that diffusivity changes in patients with the C9ORF72 repeat expansion occur 30 years before the onset of symptoms, and occur earlier than diffusivity changes in MAPT and GRN carriers260. Disruptions in functional connectivity in patients with the C9ORF72 repeat expansion have been observed to overlap with those observed in sporadic bvFTD, with disruptions of the salience network and sensorimotor network in both symptomatic262 and asymptomatic carriers254. This body of work demonstrates that measures from both structural and functional imaging have potential as early disease biomarkers in genetic FTD, although the optimum neuroimaging modality is still unclear.

Elevated uptake has been observed in patients with FTD mutations on tau-PET imaging. The distribution of uptake in the MAPT mutations typically mirrors the patterns of neurodegeneration, although the degree of uptake varies across the different MAPT mutations due to differences in the characteristic tau isoforms that are deposited in the brain (Figure 8). Hence, tau mutations, such as V337M and R406W, which deposit 3R+4R isoforms have high levels of uptake on tau-PET akin to the levels of uptake observed in Alzheimer’s dementia126,263–265, whereas mutations that deposit 4R isoforms of tau, such as N279K, S305N and 10+16, show milder uptake265–267. Therefore, tau-PET imaging shows promise as a useful neuroimaging modality in some of the MAPT mutations. As discussed above, it is unclear what the ligand is binding to in the 4R MAPT cases. The underlying mechanism for elevated uptake in GRN and C9ORF72 carriers126 is also unclear and more work is needed to understand these findings.

Figure 8: Representative renderings of tau-PET uptake in MAPT mutations relative to Alzheimer’s dementia.

Tau PET global distributions are displayed on individual participant’s brain renderings for 3 participants: (A) patients with 4R MAPT with marginally elevated levels of tau PET signal; (B) patients with mixed 3R/4R MAPT, and (C) a representative patient with Alzheimer’s dementia. Figure reproduced with permission from265.

Summary

The past few decades of neuroimaging research in bvFTD have provided potential disease biomarkers and taught us a lot about the breakdowns in brain structure and function, and the relationship between clinical symptoms and brain abnormalities in bvFTD. This knowledge has improved our ability to inform patients and their families, provide more targeted diagnoses and prognostic estimates, and provided outcomes measures that can be used to track disease progression for clinical treatment trials. However, we still lack definitive biomarkers of underlying pathology in FTD. Molecular PET imaging shows promise but ligands that better target different tau isoforms, and ligands that target FTLD-TDP, will be essential for FTD.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Whitwell is funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01-DC12519, R01-AG50603, R01-NS89757, R21-NS94684 and R01-DC14942).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 9):2456–2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warrington EK. The selective impairment of semantic memory. Q J Exp Psychol. 1975;27(4):635–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duffy J Apraxia of Speech in degenerative neurologic disease. Aphasiology. 2006;20(6):511–527. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung Y, Duffy JR, Josephs KA. Primary progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Semin Neurol. 2013;33(4):342–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mesulam MM. Slowly progressive aphasia without generalized dementia. Ann Neurol. 1982;11(6):592–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, et al. Characterizing a neurodegenerative syndrome: primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 5):1522–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, et al. The evolution of primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 10):2783–2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, et al. Clinicopathological and imaging correlates of progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 6):1385–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tetzloff KA, Duffy JR, Clark HM, et al. Longitudinal structural and molecular neuroimaging in agrammatic primary progressive aphasia. Brain. 2018;141(1):302–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tetzloff KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, et al. Clinical and imaging progression over 10 years in a patient with primary progressive apraxia of speech and autopsy-confirmed corticobasal degeneration. Neurocase. 2018;24(2):111–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumann M, Rademakers R, Roeber S, Baker M, Kretzschmar HA, Mackenzie IR. A new subtype of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with FUS pathology. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 11):2922–2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Josephs KA. Frontotemporal dementia and related disorders: deciphering the enigma. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(1):4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Josephs KA, Hodges JR, Snowden JS, et al. Neuropathological background of phenotypical variability in frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122(2):137–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickson DW. Neuropathology of Pick’s disease. Neurology. 2001;56(11 Suppl 4):S16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauw JJ, Daniel SE, Dickson D, et al. Preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome (progressive supranuclear palsy). Neurology. 1994;44(11):2015–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickson DW, Bergeron C, Chin SS, et al. Office of Rare Diseases neuropathologic criteria for corticobasal degeneration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61(11):935–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kouri N, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, Rademakers R, Dickson DW. Corticobasal degeneration: a pathologically distinct 4R tauopathy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(5):263–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampathu DM, Neumann M, Kwong LK, et al. Pathological heterogeneity of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions delineated by ubiquitin immunohistochemistry and novel monoclonal antibodies. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(4):1343–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackenzie IR, Baborie A, Pickering-Brown S, et al. Heterogeneity of ubiquitin pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: classification and relation to clinical phenotype. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2006;112(5):539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, et al. Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(1):5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cairns NJ, Grossman M, Arnold SE, et al. Clinical and neuropathologic variation in neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease. Neurology. 2004;63(8):1376–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Josephs KA, Holton JL, Rossor MN, et al. Neurofilament inclusion body disease: a new proteinopathy? Brain. 2003;126(Pt 10):2291–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kusaka H, Matsumoto S, Imai T. An adult-onset case of sporadic motor neuron disease with basophilic inclusions. Acta Neuropathol. 1990;80(6):660–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munoz DG, Neumann M, Kusaka H, et al. FUS pathology in basophilic inclusion body disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118(5):617–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josephs KA, Lin WL, Ahmed Z, Stroh DA, Graff-Radford NR, Dickson DW. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive, but TDP-43-negative inclusions. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116(2):159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackenzie IR, Foti D, Woulfe J, Hurwitz TA. Atypical frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive, TDP-43-negative neuronal inclusions. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 5):1282–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spinelli EG, Mandelli ML, Miller ZA, et al. Typical and atypical pathology in primary progressive aphasia variants. Ann Neurol. 2017;81(3):430–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson JK, Head E, Kim R, Starr A, Cotman CW. Clinical and pathological evidence for a frontal variant of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(10):1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boccardi M, Sabattoli F, Laakso MP, et al. Frontotemporal dementia as a neural system disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(1):37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosen HJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Goldman WP, et al. Patterns of brain atrophy in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. Neurology. 2002;58(2):198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salmon E, Garraux G, Delbeuck X, et al. Predominant ventromedial frontopolar metabolic impairment in frontotemporal dementia. Neuroimage. 2003;20(1):435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimmer T, Diehl J, Drzezga A, Forstl H, Kurz A. Region-specific decline of cerebral glucose metabolism in patients with frontotemporal dementia: a prospective 18F-FDG-PET study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18(1):32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diehl J, Grimmer T, Drzezga A, Riemenschneider M, Forstl H, Kurz A. Cerebral metabolic patterns at early stages of frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. A PET study. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(8):1051–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garraux G, Salmon E, Degueldre C, Lemaire C, Laureys S, Franck G. Comparison of impaired subcortico-frontal metabolic networks in normal aging, subcortico-frontal dementia, and cortical frontal dementia. Neuroimage. 1999;10(2):149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeong Y, Cho SS, Park JM, et al. 18F-FDG PET findings in frontotemporal dementia: an SPM analysis of 29 patients. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(2):233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishii K, Sakamoto S, Sasaki M, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolism in patients with frontotemporal dementia. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(11):1875–1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan PL, Song W, Yang J, et al. Gray matter atrophy in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;33(2–3):141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raczka KA, Becker G, Seese A, et al. Executive and behavioral deficits share common neural substrates in frontotemporal lobar degeneration - a pilot FDG-PET study. Psychiatry Res. 2010;182(3):274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schroeter ML, Vogt B, Frisch S, et al. Dissociating behavioral disorders in early dementia-An FDG-PET study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;194(3):235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitwell JL, Xu J, Mandrekar J, et al. Frontal asymmetry in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: clinicoimaging and pathogenetic correlates. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(2):636–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosen HJ, Allison SC, Schauer GF, Gorno-Tempini ML, Weiner MW, Miller BL. Neuroanatomical correlates of behavioural disorders in dementia. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 11):2612–2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters F, Perani D, Herholz K, et al. Orbitofrontal dysfunction related to both apathy and disinhibition in frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;21(5–6):373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hornberger M, Geng J, Hodges JR. Convergent grey and white matter evidence of orbitofrontal cortex changes related to disinhibition in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 9):2502–2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krueger CE, Laluz V, Rosen HJ, Neuhaus JM, Miller BL, Kramer JH. Double dissociation in the anatomy of socioemotional disinhibition and executive functioning in dementia. Neuropsychology. 2011;25(2):249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Massimo L, Powers C, Moore P, et al. Neuroanatomy of apathy and disinhibition in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27(1):96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zamboni G, Huey ED, Krueger F, Nichelli PF, Grafman J. Apathy and disinhibition in frontotemporal dementia: Insights into their neural correlates. Neurology. 2008;71(10):736–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitwell JL, Sampson EL, Loy CT, et al. VBM signatures of abnormal eating behaviours in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neuroimage. 2007;35(1):207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woolley JD, Gorno-Tempini ML, Seeley WW, et al. Binge eating is associated with right orbitofrontal-insular-striatal atrophy in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2007;69(14):1424–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jakabek D, Power BD, Macfarlane MD, et al. Regional structural hypo- and hyperconnectivity of frontal-striatal and frontal-thalamic pathways in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39(10):4083–4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bede P, Omer T, Finegan E, et al. Connectivity-based characterisation of subcortical grey matter pathology in frontotemporal dementia and ALS: a multimodal neuroimaging study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12(6):1696–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmed RM, Goldberg ZL, Kaizik C, et al. Neural correlates of changes in sexual function in frontotemporal dementia: implications for reward and physiological functioning. J Neurol. 2018;265(11):2562–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Macfarlane MD, Jakabek D, Walterfang M, et al. Striatal Atrophy in the Behavioural Variant of Frontotemporal Dementia: Correlation with Diagnosis, Negative Symptoms and Disease Severity. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bertoux M, O’Callaghan C, Flanagan E, Hodges JR, Hornberger M. Fronto-Striatal Atrophy in Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Neurol. 2015;6:147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moller C, Dieleman N, van der Flier WM, et al. More atrophy of deep gray matter structures in frontotemporal dementia compared to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44(2):635–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eslinger PJ, Moore P, Antani S, Anderson C, Grossman M. Apathy in frontotemporal dementia: behavioral and neuroimaging correlates. Behav Neurol. 2012;25(2):127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halabi C, Halabi A, Dean DL, et al. Patterns of striatal degeneration in frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27(1):74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Jack CR, Jr. Anatomic correlates of stereotypies in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29(12):1859–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Looi JC, Walterfang M, Styner M, et al. Shape analysis of the neostriatum in subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: neuroanatomically significant regional morphologic change. Psychiatry Res. 2011;191(2):98–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perry DC, Whitwell JL, Boeve BF, et al. Voxel-based morphometry in patients with obsessive-compulsive behaviors in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(6):911–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Frings L, Mader I, Landwehrmeyer BG, Weiller C, Hull M, Huppertz HJ. Quantifying change in individual subjects affected by frontotemporal lobar degeneration using automated longitudinal MRI volumetry. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33(7):1526–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krueger CE, Dean DL, Rosen HJ, et al. Longitudinal rates of lobar atrophy in frontotemporal dementia, semantic dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(1):43–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brambati SM, Renda NC, Rankin KP, et al. A tensor based morphometry study of longitudinal gray matter contraction in FTD. Neuroimage. 2007;35(3):998–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu PH, Mendez MF, Lee GJ, et al. Patterns of brain atrophy in clinical variants of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;35(1–2):34–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gordon E, Rohrer JD, Kim LG, et al. Measuring disease progression in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a clinical and MRI study. Neurology. 2010;74(8):666–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frings L, Yew B, Flanagan E, et al. Longitudinal grey and white matter changes in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moller C, Hafkemeijer A, Pijnenburg YAL, et al. Different patterns of cortical gray matter loss over time in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;38:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Seeley WW, Crawford R, Rascovsky K, et al. Frontal paralimbic network atrophy in very mild behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(2):249–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Borroni B, Cosseddu M, Pilotto A, et al. Early stage of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: clinical and neuroimaging correlates. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(11):3108–3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ranasinghe KG, Rankin KP, Pressman PS, et al. Distinct Subtypes of Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia Based on Patterns of Network Degeneration. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(9):1078–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bruun M, Koikkalainen J, Rhodius-Meester HFM, et al. Detecting frontotemporal dementia syndromes using MRI biomarkers. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;22:101711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cerami C, Dodich A, Lettieri G, et al. Different FDG-PET metabolic patterns at single-subject level in the behavioral variant of fronto-temporal dementia. Cortex. 2016;83:101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Salmon E, Kerrouche N, Herholz K, et al. Decomposition of metabolic brain clusters in the frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia. Neuroimage. 2006;30(3):871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Whitwell JL, Przybelski SA, Weigand SD, et al. Distinct anatomical subtypes of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia: a cluster analysis study. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 11):2932–2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Josephs KA Jr., Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, et al. Predicting functional decline in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 2):432–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Davies RR, Kipps CM, Mitchell J, Kril JJ, Halliday GM, Hodges JR. Progression in frontotemporal dementia: identifying a benign behavioral variant by magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(11):1627–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kipps CM, Davies RR, Mitchell J, Kril JJ, Halliday GM, Hodges JR. Clinical significance of lobar atrophy in frontotemporal dementia: application of an MRI visual rating scale. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23(5):334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Devenney E, Swinn T, Mioshi E, et al. The behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia phenocopy syndrome is a distinct entity - evidence from a longitudinal study. BMC Neurol. 2018;18(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Jack CR, Parisi JE, Dickson DW. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration without lobar atrophy. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(11):1632–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Whitwell JL, Jack CR Jr., Senjem ML, Josephs KA. Patterns of atrophy in pathologically confirmed FTLD with and without motor neuron degeneration. Neurology. 2006;66(1):102–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chang JL, Lomen-Hoerth C, Murphy J, et al. A voxel-based morphometry study of patterns of brain atrophy in ALS and ALS/FTLD. Neurology. 2005;65(1):75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lillo P, Mioshi E, Burrell JR, Kiernan MC, Hodges JR, Hornberger M. Grey and white matter changes across the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal dementia continuum. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cajanus A, Hall A, Koikkalainen J, et al. Automatic MRI Quantifying Methods in Behavioral-Variant Frontotemporal Dementia Diagnosis. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2018;8(1):51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Meyer S, Mueller K, Stuke K, et al. Predicting behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia with pattern classification in multi-center structural MRI data. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;14:656–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moller C, Pijnenburg YA, van der Flier WM, et al. Alzheimer Disease and Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia: Automatic Classification Based on Cortical Atrophy for Single-Subject Diagnosis. Radiology. 2016;279(3):838–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nazem A, Tang CC, Spetsieris P, et al. A multivariate metabolic imaging marker for behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2018;10:583–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Foster NL, Heidebrink JL, Clark CM, et al. FDG-PET improves accuracy in distinguishing frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 10):2616–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kerklaan BJ, van Berckel BN, Herholz K, et al. The added value of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography in the diagnosis of the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2014;29(7):607–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vijverberg EG, Wattjes MP, Dols A, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of MRI and Additional [18F]FDG-PET for Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia in Patients with Late Onset Behavioral Changes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;53(4):1287–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dukart J, Mueller K, Horstmann A, et al. Combined evaluation of FDG-PET and MRI improves detection and differentiation of dementia. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e18111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pijnenburg YA, Mulder JL, van Swieten JC, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of consensus diagnostic criteria for frontotemporal dementia in a memory clinic population. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25(2):157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Agosta F, Scola E, Canu E, et al. White Matter Damage in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration Spectrum. Cereb Cortex. 2011;[Epub]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Whitwell JL, Avula R, Senjem ML, et al. Gray and white matter water diffusion in the syndromic variants of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2010;74(16):1279–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang Y, Schuff N, Du AT, et al. White matter damage in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease measured by diffusion MRI. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 9):2579–2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Borroni B, Brambati SM, Agosti C, et al. Evidence of white matter changes on diffusion tensor imaging in frontotemporal dementia. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(2):246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Daianu M, Mendez MF, Baboyan VG, et al. An advanced white matter tract analysis in frontotemporal dementia and early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016;10(4):1038–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mahoney CJ, Ridgway GR, Malone IB, et al. Profiles of white matter tract pathology in frontotemporal dementia. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(8):4163–4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kassubek J, Muller HP, Del Tredici K, et al. Longitudinal Diffusion Tensor Imaging Resembles Patterns of Pathology Progression in Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia (bvFTD). Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Elahi FM, Marx G, Cobigo Y, et al. Longitudinal white matter change in frontotemporal dementia subtypes and sporadic late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;16:595–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mahoney CJ, Simpson IJ, Nicholas JM, et al. Longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging in frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(1):33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lam BY, Halliday GM, Irish M, Hodges JR, Piguet O. Longitudinal white matter changes in frontotemporal dementia subtypes. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(7):3547–3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yu J, Lee TMC, Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration Neuroimaging I. The longitudinal decline of white matter microstructural integrity in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and its association with executive function. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;76:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kramer J, Lueg G, Schiffler P, et al. Diagnostic Value of Diffusion Tensor Imaging and Positron Emission Tomography in Early Stages of Frontotemporal Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(1):239–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Agosta F, Galantucci S, Magnani G, et al. MRI signatures of the frontotemporal lobar degeneration continuum. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36(7):2602–2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Santillo AF, Martensson J, Lindberg O, et al. Diffusion tensor tractography versus volumetric imaging in the diagnosis of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e66932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang Y, Tartaglia MC, Schuff N, et al. MRI signatures of brain macrostructural atrophy and microstructural degradation in frontotemporal lobar degeneration subtypes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(2):431–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Moller C, Hafkemeijer A, Pijnenburg YA, et al. Joint assessment of white matter integrity, cortical and subcortical atrophy to distinguish AD from behavioral variant FTD: A two-center study. Neuroimage Clin. 2015;9:418–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, Avula R, et al. Altered functional connectivity in asymptomatic MAPT subjects: a comparison to bvFTD. Neurology. 2011;77(9):866–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhou J, Greicius MD, Gennatas ED, et al. Divergent network connectivity changes in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 5):1352–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Farb NA, Grady CL, Strother S, et al. Abnormal network connectivity in frontotemporal dementia: Evidence for prefrontal isolation. Cortex. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Filippi M, Agosta F, Scola E, et al. Functional network connectivity in the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Cortex. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tuovinen T, Rytty R, Moilanen V, et al. The Effect of Gray Matter ICA and Coefficient of Variation Mapping of BOLD Data on the Detection of Functional Connectivity Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease and bvFTD. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Filippi M, Agosta F, Scola E, et al. Functional network connectivity in the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Cortex. 2013;49(9):2389–2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Reyes P, Ortega-Merchan MP, Rueda A, et al. Functional Connectivity Changes in Behavioral, Semantic, and Nonfluent Variants of Frontotemporal Dementia. Behav Neurol. 2018;2018:9684129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Farb NA, Grady CL, Strother S, et al. Abnormal network connectivity in frontotemporal dementia: evidence for prefrontal isolation. Cortex. 2013;49(7):1856–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sedeno L, Couto B, Garcia-Cordero I, et al. Brain Network Organization and Social Executive Performance in Frontotemporal Dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2016;22(2):250–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Day GS, Farb NA, Tang-Wai DF, et al. Salience network resting-state activity: prediction of frontotemporal dementia progression. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(10):1249–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hafkemeijer A, Moller C, Dopper EG, et al. A Longitudinal Study on Resting State Functional Connectivity in Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(2):521–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Agosta F, Sala S, Valsasina P, et al. Brain network connectivity assessed using graph theory in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2013;81(2):134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hafkemeijer A, Moller C, Dopper EG, et al. Resting state functional connectivity differences between behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Filippi M, Basaia S, Canu E, et al. Brain network connectivity differs in early-onset neurodegenerative dementia. Neurology. 2017;89(17):1764–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bouts M, Moller C, Hafkemeijer A, et al. Single Subject Classification of Alzheimer’s Disease and Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia Using Anatomical, Diffusion Tensor, and Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(4):1827–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Son HJ, Oh JS, Roh JH, et al. Differences in gray and white matter (18)F-THK5351 uptake between behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia and other dementias. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46(2):357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Nam G, Jeong HJ, Kang JM, et al. (18)F-THK5351 PET Imaging in the Behavioral Variant of Frontotemporal Dementia. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2018;17(4):163–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tsai RM, Bejanin A, Lesman-Segev O, et al. (18)F-flortaucipir (AV-1451) tau PET in frontotemporal dementia syndromes. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cho H, Seo SW, Choi JY, et al. Predominant subcortical accumulation of (18)F-flortaucipir binding in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;66:112–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lowe VJ, Curran G, Fang P, et al. An autoradiographic evaluation of AV-1451 Tau PET in dementia. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4(1):58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ryan KA, Hammers D, DeLeon A, et al. Agreement among neuropsychological and behavioral data and PiB findings in diagnosing Frontotemporal Dementia. J Clin Neurosci. 2017;44:128–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Chan D, Fox NC, Scahill RI, et al. Patterns of temporal lobe atrophy in semantic dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of neurology. 2001;49(4):433–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Galton CJ, Patterson K, Graham K, et al. Differing patterns of temporal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease and semantic dementia. Neurology. 2001;57(2):216–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]