Abstract

Recent measles and pertussis outbreaks in the US have focused national attention on state laws governing exemptions from mandatory vaccines for school entry. After several years of increases in nonmedical exemptions in California, the state assembly passed Assembly Bill 2109 in 2012, making nonmedical exemptions more difficult to obtain by requiring parents to obtain a signature from a health care provider. We used data from the California Department of Public Health to describe changes in the overall prevalence of personal belief exemptions and compositional changes in immunization status for the school years 2012–2013 through 2015–2016. Following the implementation of Assembly Bill 2109, the statewide exemption rate declined from 3.1% in 2013 to 2.5% in 2014 and then to 2.3% in 2015, representing a 25% reduction from the 2013 peak. Continued surveillance of exemption rates and vaccine refusal are needed to monitor and protect herd immunity against vaccine-preventable diseases.

Keywords: Immunization, Vaccines, School health, State policy, Surveillance, Infectious disease

1. Introduction

The routine childhood immunization schedule protects against 17 diseases, and prevents millions of cases of diseases and thousands of deaths in every US birth cohort [1,2]. To maintain high rates of immunization coverage, each US state has laws mandating required immunizations for school entry [3]. State law in all 50 states provides for medical exemptions to immunization mandates, and most states also provide for nonmedical exemptions. Allowed nonmedical exemptions can be further categorized as personal belief, philosophical, and/or religious.

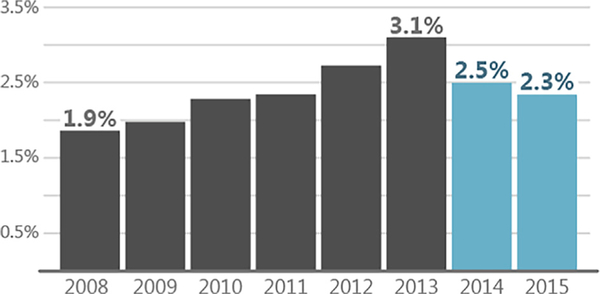

Recent measles and pertussis outbreaks [4,5] have focused national attention on these state laws governing exemptions from school-entry immunization mandates. In California, the focus of the present study, nonmedical exemptions are referred to as personal belief exemptions (PBEs). PBEs were very easy for California parents to obtain prior to 2012, requiring only a parent signature on a preprinted affidavit on the back of the child’s school immunization record. Religious and other types of nonmedical exemptions were not separately delineated or recorded. After several years of steady increases in PBEs in the state (see Fig. 1), the California State Assembly passed Assembly Bill 2109 (AB2109) in 2012. AB2109, which went into effect in January 2014, made PBEs more difficult to obtain. The new law required parents to obtain a signature from an authorized health care provider (HCP) stating that the parent had received information about the risks and benefits of immunization. In addition, a new, separate religious exemption option was added to the state’s immunization policy in the Governor’s signing statement [6].

Fig. 1.

Personal belief exemption rate from mandated school-entry immunizations, California kindergarteners, 2008–2015.

Less than one year after AB2109 went into effect, and only three months into the first school year under AB2109, “Disneyland” measles outbreak of early 2015 raised additional concerns about intentional undervaccination in the state [7]. California state legislators moved quickly to enact Senate Bill 277 (SB277) in July 2015, which completely eliminated personal belief exemptions as of July 2016 [8]. California is now only the third state (along with Mississippi and West Virginia) with no allowance for nonmedical exemptions, and the first to eliminate previously allowed nonmedical exemptions in more than thirty years.

The behavioral response to this rapid succession of new exemption laws is a relevant policy issue to the many other states considering or implementing similar exemption laws [9]. Previous research on exemption laws has found a consistent relationship between easier exemption requirements and higher exemption rates; and between exemption rates and both individual and population disease risk [10]. However, much of this prior literature looks at cases of exemption laws becoming less stringent, usually through the addition of philosophical or personal belief exemptions to existing religious exemptions. For example, Arkansas saw a steep increase in the number of nonmedical exemptions granted after philosophical exemptions were introduced in 2003 [11,12].

Less is known about the response to more stringent exemption regimes, as legislated by AB2109 and SB277 in California. While the response to the dramatic changes mandated by SB277 is still unfolding, the two-year experience under AB2109 can provide insight as to statewide response to a bill requiring slightly more effort (in the form of a healthcare provider signature) in order to obtain a personal belief exemption. The goal of this study was to describe changes in the overall prevalence of personal belief exemptions and compositional changes in immunization status for four successive kindergarten cohorts in California (school years 2012–2013 through 2015–2016), which span the implementation of AB2109 in January 2014.

2. Material and methods

Each fall, the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) collects kindergarten enrollment, immunization status, and exemption data from all public and private schools offering kindergarten. Data for all schools with at least 10 kindergarten students are publicly available [13], and include the number of kindergarteners who are up-to-date on immunizations, have a permanent medical exemption, have a PBE, or are granted conditional admission. Conditional admission is meant to refer only to students who are not up-to-date on mandated immunizations, but who are also not currently eligible to receive a vaccine dose [14]. For example, a child may just have received the first dose of the Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) vaccine, but is not eligible to receive the second dose until four weeks later [15]. The conditional admissions status typically applies to students who begin the child immunization series late (e.g., right before kindergarten registration); however, CDPH has reported that many schools apply the conditional admission status more broadly to students with incomplete or missing immunization records for any reason [16]. It is important to note that a PBE can be granted for one or more mandated immunizations, so a kindergartener with a PBE may be exempted, for example, only from the MMR vaccine, or from all mandated immunizations.

Beginning with the 2014–15 school year, the CDPH surveillance data disaggregates the number of students with PBEs into three categories: PBEs obtained by getting a health care provider signature, PBEs obtained by claiming a religious exemption (which does not require a provider signature), and PBEs already in place prior to implementation of the new law (referred to as “Pre-January 2014 PBEs”). Pre-January 2014 PBEs were primarily obtained by transitional kindergarten (TK) students for the 2013–14 school year, and were honored for the 2014–15 school year. TK students enroll in a two-year kindergarten program, and are counted in the kindergarten assessment data in both of their TK school years. Beginning in 2015–16, each school also reports the number of kindergarteners who are overdue for mandated vaccine doses (but who are not otherwise exempted or conditionally admitted); these students can be legally excluded from school due to incomplete immunizations and noncompliance with exemption law.

Data for the 2001–02 through 2015–16 school years were compiled and analyzed. An interrupted time-series analysis was conducted on the annual statewide PBE rate to evaluate the overall trends in PBEs before and after AB2109 was implemented. Kindergarten immunization status and exemption type rates were also calculated by year, school type (public vs. private), and by terciles of 2011–13 average school-level kindergarten PBE rate. Terciles were created by dividing schools into three equally-sized groups by average school-level kindergarten PBE rate for the three-year period 2011–2013. Terciles were labeled “low”, “medium”, and “high”, reflecting the schools’ pre-2014 PBE rate. School-level exemption rates were weighted by the school’s total kindergarten enrollment. Rates are presented without confidence intervals or significance testing as these data comprise the full population of schools with at least 10 kindergarteners. All analyses were conducted in 2018. The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania.

3. Results

Decline in PBE rate.

Following the implementation of Assembly Bill 2109, the statewide PBE rate declined sharply, from 3.1% in Fall 2013 to 2.5% in Fall 2014 and then to 2.3% in Fall 2015, or a 25% reduction from the 2013 peak (Fig. 1). This represents a decline from 16,416 (Fall 2013) to 12,763 (Fall 2015) PBEs, in a statewide annual kindergarten cohort of more than 500,000 (Table 1). An interrupted time series analysis showed a baseline (2001) estimated PBE rate of 0.78%; PBE rates then increased significantly up to 2013 by 0.16 percentage points per year (P<.0005, CI [0.11, 0.22]). In 2014 (when AB2109 was implemented), a significant decrease of 0.42 percentage points (P = .031, CI [−0.80, −0.05]) was observed, as well as a significant decrease in the annual PBE rate trend of 0.32 percentage points (P < .0005, CI [−0.38, −0.27]).

Table 1.

Enrollment, immunization status, and exemption statistics, California kindergarteners, for school years 2012–13 through 2015–16.

| 2012–13 | 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total kindergarten enrollment | 525,536 | 530,530 | 531,940 | 547,520 |

| Schools, N | ||||

| Kindergarteners by Immunization Status (N) | ||||

| Up-to-Date | 474,871 | 478,701 | 481,256 | 508,693 |

| Conditional admission | 35,471 | 34,430 | 36,417 | 24,201 |

| Personal Belief Exemption (PBE) | 14,294 | 16,416 | 13,257 | 12,763 |

| Permanent Medical Exemption (PME) | 900 | 983 | 1010 | 916 |

| Overdue, can be excluded | - | - | - | 947 |

| Kindergarteners by immunization status (%) | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Up-to-Date | 90.36% | 90.23% | 90.47% | 92.91% |

| Conditional admission | 6.75% | 6.49% | 6.85% | 4.42% |

| Personal Belief Exemption (PBE) | 2.72% | 3.09% | 2.49% | 2.33% |

| Permanent Medical Exemption (PME) | 0.17% | 0.19% | 0.19% | 0.17% |

| Overdue, subject to exclusion | 0.17% | |||

| Personal belief exemptions by type (% of all PBEs) | ||||

| Prior to AB2109 implementation | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| Health care provider counseled | 65.1% | 76.7% | ||

| Religious | 20.2% | 23.3% | ||

| Pre-January 2014 | 14.7% | 0.0% | ||

| Change in PBE rate from 2013 to 2014 | ||||

| Low PBE rate in 2013–2014 | ||||

| Public Schools | 0.23% | 0.23% | ||

| Private schools | 1.43% | 1.03% | ||

| Middle PBE rate in 2013–2014 | ||||

| Public schools | −0.27% | −0.36% | ||

| Private schools | 0.24% | 0.23% | ||

| High PBE rate in 2013–2014 | ||||

| Public schools | −2.22% | −2.72% | ||

| Private schools | −2.24% | −3.21% | ||

Source: California Department of Public Health, Kindergarten Immunization Assessment, 2012–13 through 2015–2016. Notes: Dataset includes kindergarten students from all school enrolling at least 10 kindergarteners. California Assembly Bill 2109 (AB2109) requiring a healthcare provider signature or religious exemption for a personal belief exemption went into effect January 1, 2014.

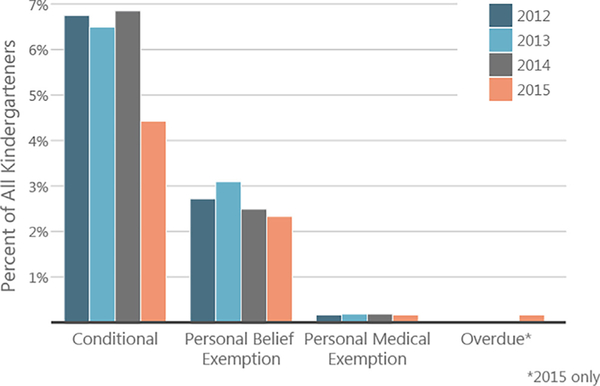

Changes in other immunization statuses.

Another notable change was the steep 23% decline in the conditional admission rate from 2014 (6.9%, 36,417 kindergarteners) to 2015 (4.4%, 24,201 kindergarteners) (Table 1, Fig. 2). Permanent medical exemption (PME) rates remained stable at 0.17–0.19% (around 900–1000 kindergarteners) over the four-year period, suggesting that parents did not substitute PMEs for PBEs following the implementation of AB2109. Beginning in 2015, the overdue rate was reported at 0.17% (947 kindergarteners).

Fig. 2.

Immunization and exemption status of kindergarteners not up-to-date on mandated school-entry immunizations, California, 2012–2015.

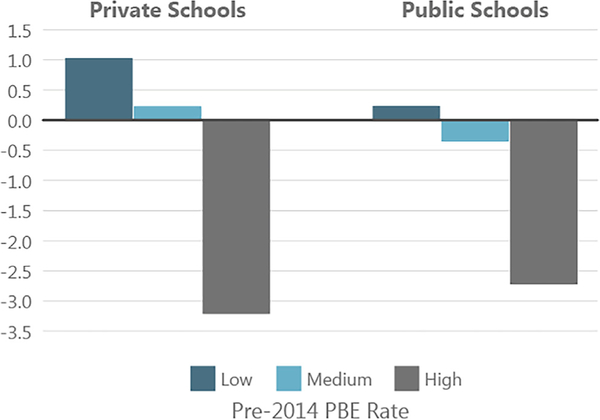

Changes in PBE rates by school type and prior PBE rate.

The largest declines in PBE rates occurred in schools in the highest tercile of pre-2014 PBE rates (3.2 percentage point decline at private schools, 2.7 percentage point decline at public schools, Table 1 and Fig. 3). Schools with moderate PBE rates changed very little from Fall 2013 to Fall 2015, and schools with low PBE rates increased slightly (1.0 percentage point in private schools and 0.23 percentage points in public schools).

Fig. 3.

Change in personal belief exemption rate from Fall 2013 to Fall 2015 by school type and pre-2014 PBE rate, California schools with at least 10 kindergarteners.

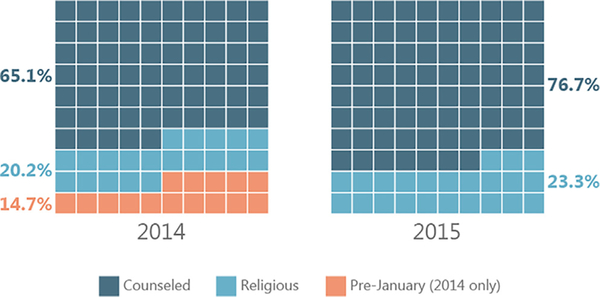

Composition of PBEs following new law.

In Fall 2014, about 65% of the 13,257 kindergarteners with PBEs obtained a HCP signature (Table 1 and Fig. 4). Only 20% (2651) used the religious exemption and fewer than 15% (1949) had a pre-January 2014 PBE in place for a two-year kindergarten program. In Fall 2015, 77% of the 12,763 kindergarteners with PBEs obtained a healthcare provider signature, and 23% used the religious exemption. Students who enrolled in their first year of a two-year kindergarten program after implementation of AB2109 were required to follow the new policy guidelines, so the “pre-January 2014” category does not exist in the 2015 data.

Fig. 4.

Personal belief exemptions by type, California kindergarteners, 2014–2015.

Use of religious exemption by school type and prior PBE rate.

Across all school types and terciles of prior PBE rates, religious exemptions were a minority of PBEs in both 2014 and 2015. The proportion of parents obtaining an exemption who invoked the religious exemption ranged from 10% in private schools with the highest PBE rates in 2014 to 29% in public schools with the lowest PBE rates in 2015. Substantial proportions of students with exemptions in Fall 2014 already had a prior exemption on file, particularly in private schools.

4. Discussion

The personal belief exemption rate from mandated school-entry immunizations in California declined substantially in the year following implementation of Assembly Bill 2109 in 2014; the decline was sustained in 2015. While the provision of a religious exemption raised concerns about an “easy out” for parents seeking exemptions (because no HCP signature was required), this option was selected by few parents obtaining an exemption in both 2014 and 2015.

After a slight increase in Fall 2014, a steep decline was also observed in the conditional admission rate in Fall 2015. Prior to the start of the 2015–16 school year, the State Controller’s Office issued an alert that schools with conditional entrant rates higher than 25% would be subject to audit. The CDPH supplemented this new policy with its Conditional Entrant Intervention Project, launched in Fall 2015, which worked with local health departments to identify schools with high rates of conditional entrants and offer them resources and training [17]. These state-level efforts likely reduced schools’ use of conditional admissions more than any direct effects of AB2109, although conditional admissions may have been used previously as a means to accommodate exemption requests or missing medical records [18]. Declines in both PBEs and conditional admissions result in an overall increase in vaccine coverage, as reflected in higher up-to-date rates in 2015 compared to prior years.

Changes in PBE rates differed by school type and by prior PBE rate. Prior to this study, it was not known whether declines in PBE rates were experienced equally across schools with different pre-AB2109 PBE rates. We observed the largest declines in schools with the highest pre-2014 PBE rates, as well as slight increases in exemptions in schools (particularly private schools) with previously low PBE rates. This finding may suggest that high PBE rates prior to AB2109 were driven at least in part by school policies and procedures (such as suggesting a PBE to parents with incomplete immunization records) that are inconsistent with the HCP signature requirement [19]. While our analysis did not address changes in the clustering of exemptions following AB2109, other recent analyses show minimal changes in spatial clustering from 2013 to 2014 and nearly randomly spatially distributed changes in NME rates and clustering from 2014 to 15 [20]. This is extremely important given that high exemption rate clusters have been associated with measles and pertussis outbreaks [21–23].

In evaluating an exemption policy change that aims to reduce exemption rates, it is crucial to consider the extent to which we can claim that high exemption rates drive vaccine-preventable disease outbreak risk. Prior work has demonstrated that the true immunization status of students with personal belief exemptions can be much higher than surveillance data would suggest [24]. That is, having a personal belief exemption does not necessarily imply that a child is completely unvaccinated; indeed, that child may have received most or even all recommended vaccines. To the extent this is true, reducing exemption rates through policy or other interventions may not reduce disease incidence. However, it is also the case, as mentioned above, that exemption rates have been associated with disease outbreak risk in several settings [21–23].

Our focused goal in this study was to describe changes in exemption rates and in the composition of exemption types among California kindergarteners following the implementation of AB2109. Within this narrow scope, we note some important limitations to our analyses. We have conducted an ecological study relating aggregate changes in exemption rates to a statewide law change; we are not able to claim that any observed changes in exemption rates were a direct result of AB2109. Several other phenomena could explain these observed changes, including a shifting of exempted children to schools with fewer than 10 kindergarteners (which are not reported in CDPH publicly available surveillance data) or to homeschooling arrangements other than charter-school based Independent Study Programs (which are reported in CDPH data if the school enrolls at least 10 kindergarteners). Changes in exemption rates or immunization status could also reflect secular changes in parental attitudes about vaccines over the same time period, or parental responses to recent disease outbreaks themselves. While changes to the mandatory vaccination schedule or conditional admissions definition during the study period could also explain exemption rate declines, we are not aware of any such changes between 2012 and 2016. Finally, we are not able to disentangle changes in rates of nonmedical exemptions that were not religiously motivated from those of religiously-motivated exemptions, both because religious exemptions were not reported separately prior to 2014 and because the religious exemption provision in AB2109 does not require any affidavit of religious membership or confirmation from a religious leader.

The rapid replacement of AB2109 with SB277 leaves only two school years (2014–15 and 2015–16) during which AB2109 was in effect. While we will not be able to assess longer-term trends following AB2109, we speculate that kindergarten PBE rates under AB2109 might have stabilized at around 2.0%–2.5%, but would likely have responded to disease outbreaks, vaccine safety and efficacy concerns raised in the media, and changes in immunization mandates. Observations about responses to the law’s incremental approach to decreasing exemption rates by increasing the effort required to obtain exemptions are important, however, as several states consider similar changes to exemption laws. Through June 2017, 41 bills concerning vaccine exemptions had been introduced in 17 states during the 2017 state legislative sessions [9]. The bills reflect diverse goals related to vaccine exemptions, but about one-third of proposed bills seek a similar increase in the administrative burden required to obtain a nonmedical exemption to the approach used in AB2109. California’s brief experience with AB2109 is likely to inform the crafting of exemption legislation for several more legislative cycles.

California entered a new era of vaccine policy in summer 2016 under SB277. Preliminary analyses of data from the 2016–17 school year [25,26] indicate that the PBE rate dropped to 0.6% (comprising primarily transitional kindergarten students with existing PBEs in place); and the conditional admission rate dropped to 1.9%. Notably, the permanent medical exemption rate more than doubled (from 0.2% to 0.5%). The “overdue” category (introduced in Fall 2015) increased to 1.0%; this group of students would likely have been considered conditional entrants prior to the 2015 initiatives to limit the use of that category. Another 0.5% were determined to be in a new category: lacking immunizations for reasons other than those specified in SB277 (such as homeschooling).

The elimination of personal belief exemptions raises the potential for both public backlash and unintended consequences [27,28]. Moreover, in most states, eliminating nonmedical exemptions is unlikely to be politically feasible. Therefore, it is important to evaluate both incremental and disruptive changes to immunization exemption laws. Such evaluations will help develop the evidence base for policy options relevant to a variety of states.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (R03HD080732) and from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Abbreviations:

- PBE

Person belief exemption

- SB277

Senate Bill 277

- AB2109

Assembly Bill 2109

- MMR

Measles Mumps Rubella

- CDPH

California Department of Public Health

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Daniel Salmon has received research funding from vaccine manufacturers Crucell and Pfizer and has served as an expert witness and consultant for Merck, a vaccine manufacturer. No other authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Hill HA, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, Kolasa M. National, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Children Aged 19–35 Months-United States, 2014. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2015;64 (33):889–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Whitney CG, Zhou F, Singleton J, Schuchat A, Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Benefits from immunization during the vaccines for children program era-United States, 1994–2013. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2014;63(16):352–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lieu TA, Ray GT, Klein NP, Chung C, Kulldorff M. Geographic clusters in underimmunization and vaccine refusal. Pediatrics 2015;135(2):280–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zipprich J, Winter K, Hacker J, Xia D, Watt J, Harriman K. Measles outbreak—California, December 2014-February 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(6):153–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Winter K, Glaser C, Watt J, Harriman K. Control CfD, prevention. Pertussis epidemic—California, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63 (48):1129–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Office of the Governor of California. AB 2109 Signing Message. 2012. Accessed September 13, 2017 at https://www.gov.ca.gov/docs/AB_2109_Signing_Message.pdf.

- [7].Jones M, Buttenheim A. Potential effects of California’s new vaccine exemption law on the prevalence and clustering of exemptions. Am J Public Health 2014;104(9):e3–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].California Senate Bill No. 277: An act to amend Sections 120325, 120335, 120370, and 120375 of, to add Section 120338 to, and to repeal Section 120365 of, the Health and Safety Code, relating to public health. 2015. Accessed September 13, 2017 at http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/15-16/bill/sen/sb_0251-0300/sb_277_bill_20150630_chaptered.pdf

- [9].Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. 2017 ASTHO State Legislative Tracking Accessed September 13, 2017 at http://www.astho.org/state-legislative-tracking/.

- [10].Wang E, Clymer J, Davis-Hayes C, Buttenheim A. Nonmedical exemptions from school immunization requirements: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2014;104(11):e62–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Thompson JW, Tyson S, Card-Higginson P, Jacobs RF, Wheeler JG, Simpson P, et al. Impact of addition of philosophical exemptions on childhood immunization rates. Am J Prev Med 2007;32(3):194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Safi H, Wheeler JG, Reeve GR, Ochoa E, Romero JR, Hopkins R, et al. Vaccine policy and Arkansas childhood immunization exemptions: A multi-year review. Am J Prev Med 2012;42(6):602–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].California Department of Public Health. Immunization Rates in Child Care and Schools. Accessed April 18, 2016 at https://archive.cdph.ca.gov/programs/immunize/Pages/ImmunizationLevels.aspx.

- [14].California Assembly Bill No. 2109: An act to amend Section 120365 of the Health and Safety Code, relating to communicable disease; 2012. Accessed September 13, 2017 at http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/11-12/bill/asm/ab_2101-2150/ab_2109_bill_20120223_introduced.pdf.

- [15].Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Catch-up Immunization Schedule. 2017. Accessed September 13, 2017 at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/catchup.html.

- [16].Adams JM. More students vaccinated as enforcement efforts increase. EdSource 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [17].California Department of Public Health Immunization Branch. 2015–2016 Conditional Entrant Intervention Project. 2016. Accessed September 13, 2017 at https://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/immunize/Documents/ConditionalEntrantInterventionEvaluationReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wheeler M, Buttenheim AM. Ready or not? School preparedness for California’s new personal beliefs exemption law. Vaccine 2014;32(22):2563–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jones M, Buttenheim A. Potential effects of California’s new vaccine exemption law on the prevalence and clustering of exemptions. Am J Public Health 2014;104(9):e3–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Delamater PL, Leslie TF, Yang YT. A spatiotemporal analysis of non-medical exemptions from vaccination: California schools before and after SB277. Soc Sci Med 2016;168:230–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Omer SB, Enger KS, Moulton LH, Halsey NA, Stokley S, Salmon DA. Geographic clustering of nonmedical exemptions to school immunization requirements and associations with geographic clustering of pertussis. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168(12):1389–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Feikin DR, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF, Salmon DA, Chen RT, Hoffman RE. Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunization. JAMA 2000;284(24):3145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Atwell JE, Van Otterloo J, Zipprich J, Winter K, Harriman K, Salmon DA, et al. Nonmedical vaccine exemptions and pertussis in California, 2010. Pediatrics 2013;132(4):624–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Buttenheim AM, Sethuraman K, Omer SB, Hanlon AL, Levy MZ, Salmon D. MMR vaccination status of children exempted from school-entry immunization mandates. Vaccine 2015;33(46):6250–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].California Department Public Health Immunization Branch. 2016–2017 Kindergarten Immunization Assessment - Executive Summary. 2017. Accessed April 24, 2017, 2017 at https://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/immunize/pages/immunizationlevels.aspx.

- [26].Delamater PL, Leslie TF, Yang YT. Change in medical exemptions from immunization in California after elimination of personal belief exemptions. Jama 2017;318(9):863–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Salmon DA, MacIntyre CR, Omer SB. Making mandatory vaccination truly compulsory: well intentioned but ill conceived. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15 (8):872–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Opel DJ, Kronman MP, Diekema DS, Marcuse EK, Duchin JS, Kodish E. Childhood vaccine exemption policy: the case for a less restrictive alternative. Pediatrics 2016;137(4):e20154230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]