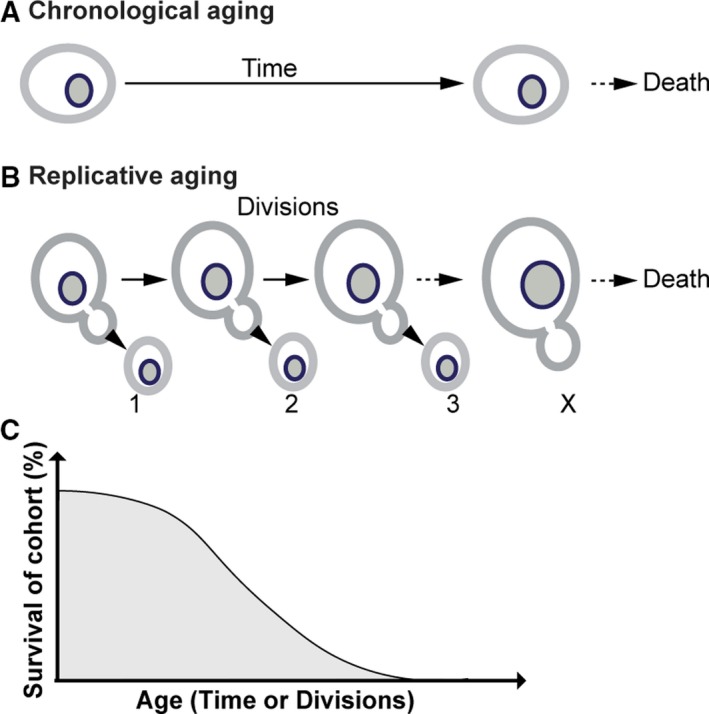

Figure 2.

Schematic representations of aging on the population and the single‐cell level. (A) Cartoon of a chronological aging baker's yeast cell. Chronological aging is the kind of aging that nondividing cells experience in time before they die of old age. Chronological aging is induced through the depletion of nutrients. Commonly used protocols to achieve nutrient depletion include growing a cell culture to a stationary phase or transferring an exponential culture to water 52. Acidification of the medium has been a cofounding factor in some chronological aging studies 53. Moreover, prolonged starvation is a stress that postmitotic cells in higher eukaryotes do not experience, and this should be considered when translating results from chronological aging studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to higher eukaryotes. A more involved way to induce chronological aging, which overcomes the limitation of severe nutrient depletion in yeast, is to provide the cells with just too little nutrients to divide, called near‐zero growth and which is performed in a retentostat 40. (B) Cartoon of a replicative aging baker's yeast cell. Dividing cells age with each completed division, therefore their age is measured in the number of completed divisions. Replicative aging in baker's yeast is triggered by the asymmetric retention of aging factors in the mother, which causes the mother to age while the daughter cell is born young. Age‐induced damage can occur in the form of damaged and nonfunctional organelles, ERCs, asymmetrically retained transmembrane proteins and protein aggregates. (C) Cartoon of a typical survival curve of a cohort of aging cells or organisms. Aging is associated with an increased risk of mortality and there is intrinsic variation in the lifespan of individual cells or organisms within one cohort. As aging occurs at very different timescales, cross‐species comparisons of changes associated with aging, as well as comparisons between chronological and replicative aging cells can be based on the survival of the cohort.