Abstract

Objective

To use the variations in neurology consultations requested by emergency department (ED) physicians to identify opportunities to implement multidisciplinary interventions in an effort to reduce ED overcrowding.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed ED visits across 3 urban hospitals to determine the top 10 most common chief complaints leading to neurology consultation. For each complaint, we evaluated the likelihood of consultation, admission rate, admitting services, and provider-to-provider variability of consultation.

Results

Of 145,331 ED encounters analyzed, 3,087 (2.2%) involved a neurology consult, most commonly with chief complaints of acute-onset neurologic deficit, subacute neurologic deficit, or altered mental status. ED providers varied most in their consultation for acute-onset neurologic deficit, dizziness, and headache. Neurology consultation was associated with a 2.3-hour-longer length of stay (LOS) (95% CI: 1.6–3.1). Headache in particular has an average of 6.7-hour-longer ED LOS associated with consultation, followed by weakness or extremity weakness (4.4 hours) and numbness (4.1 hours). The largest estimated cumulative difference (number of patients with the specific consultation multiplied by estimated difference in LOS) belongs to headache, altered mental status, and seizures.

Conclusion

A systematic approach to identify variability in neurology consultation utilization and its effect on ED LOS helps pinpoint the conditions most likely to benefit from protocolized pathways.

Overcrowding in emergency departments (EDs), especially at urban medical centers, is a growing public health concern,1,2 and much has been written about reducing ED length of stay (LOS).3,4 Subspecialty consultation has been identified as a major contributor to ED LOS, involving 20%–40% of ED visits, with highest frequencies at urban academic hospitals.5 Neurologists are among the most frequently consulted, and given the expanding role of therapeutics for acute ischemic stroke, consulting neurologists' capacity to attend to urgent situations must be preserved. Hospitals have multiple incentives to decrease avoidable neurologic consultations and to optimize the number of touch points in each consultation. The utilization of neurology consultation in EDs is not well characterized.5 Consultations, in general, have been associated with increased LOS in the ED,4,6,7 and time waiting for consultation comprises approximately one-fourth to one-half of the LOS.8

Consequently, there is widespread interest in interventions that reduce the time to or need for consultation,4,6,9 which we broadly classify. In general, policies prioritize consultants' work in the ED over other duties throughout the hospital. On the other hand, pathways target specific patient conditions and design clinical management steps to follow. Pathways require more consensus across roles (e.g., physicians, nurses, and advanced practice providers) and specialties (e.g., ED and neurology). They may also require training (e.g., teaching a nuanced examination maneuver) and continuous improvement. Pathways can be rewarding, but because of the considerable upfront cost, deciding where to apply these pathways can be a challenge.

In this study, we systematically determined the neurologic chief complaints that contribute most to ED LOS and neurology consulting workload and the ones with the highest provider-to-provider or temporal variability—and thereby the ones most likely to benefit from multidisciplinary interventions.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective analysis was completed as part of a quality improvement project to improve the efficiency of neurologic consultation and minimize ED LOS.

Among patients seen in the ED, we first identified the chief complaints most frequently associated with neurologic consultation and estimated their effect on ED LOS. We then assessed consultation variability with respect to time and ED provider. Next, we assessed the likelihood of discharge from the ED in these conditions. Finally, we used prevalence and ED LOS information to estimate the total opportunity size for each condition.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

During the conceptualization of the study design, institutional review board (IRB) approval was sought and reviewed by the University of Pennsylvania IRB. We received a letter of exemption on the basis of quality improvement. The potential publication of this work was included in the IRB application.

Data sources and variables

We obtained deidentified data from the hospital's electronic medical record, which included basic demographics (age and sex), ED triage-documented chief complaint, Emergency Severity Index (ESI), ED disposition, ED LOS, ED provider, ED arrival time, and presence of neurology consultation. Chief complaint, diagnosis, age, ED provider, ED arrival time, and LOS were all required fields. We only used required data fields to ensure a complete data set for our analysis. Presence of a neurology consultation was determined by the presence of an electronic order for inpatient neurology consultation and a completed consultation note.

Although acquisition of MRI and other testing may contribute to LOS, this was out of the scope of the current study. We did not include these as independent variables because of the variability of imaging availability across different facilities.

Setting

Neurology consultation is available at all hours in all 3 hospitals. At these 3 hospitals, neurology is the most frequently consulted service in the ED. ED attending physicians typically work at 1–2 sites. The ED and neurology residents rotate between all sites. Neurology residents are available, in-house, for ED consultation at all hours at all facilities studied. They are the first neurologists to see all ED consultations. Neurology attendings and stroke fellows are present and see all new consultations that arrive during typical daytime hours, but they are accessible by the residents by telephone at all hours. At some sites, neurology attendings may have concurrent inpatient or outpatient clinical duties.

Two of the 3 hospitals have dedicated neurology inpatient services. One hospital is designated an Advanced Comprehensive Stroke Center by the Joint Commission; the other 2 are designated Advanced Primary Stroke Centers. A neurology consultation may be requested by the ED or by another inpatient service seeing a patient in the ED, but a neurology consultation is required before admission to a neurology service.

Inclusion criteria

We reviewed all ED visits from April 2017 to April 2018 that took place within 3 urban academic hospitals—all part of a single health system.

In our EDs, a triage nurse assigns and documents a chief complaint to each patient on presentation to the ED, setting in motion protocols as need be. Triage nurses are trained to look for the presence of acute-onset neurologic deficits, setting in motion our “stroke alert.” For clarity, we refer to these conditions as “chief complaints with acute-onset neurologic deficit.” These are the conditions where a health care professional has triaged a stroke response on transit or where the triage nurse's assessment includes a medium or high clinical suspicion of acute stroke. The chief complaint “rule out cerebrovascular vascular accident” is assigned in cases of low clinical suspicion of acute stroke. Again for clarity, we refer to these here as “chief complaints with subacute neurologic deficit.”

We defined ED provider as the attending physician. Although management decisions are made in part by resident physicians and advanced practitioners when appropriate, we used ED attendings only because they are the final decision maker in case of discrepancy.

Neurology consultations requested for patients already admitted to inpatient services were not included. In addition to neurology consultations, one of the studied hospitals has a pathway for incoming acute stroke interhospital transfers. Patients from these transfers are managed by the neurology consultation team but assigned to beds in the neurology service or neurology intensive care unit service, so they are not ED patients. These patients were excluded from this project.

Statistical methods

We used descriptive statistics to describe characteristics of the populations with and without neurology consultation. These characteristics included age, sex, ESI score, ED LOS, ED disposition, and chief complaint.

Some of these patients did not have a neurology consultation. We studied the differences between those who did and did not have a neurology consultation to study any systematic variation, quantify the potential impact of reducing or expediting neurologic consults, and investigate the possibility of selection bias of patients for whom neurologists are consulted.

We focused our data analysis on the subset of patients with one of the top 10 most common chief complaints for which neurology was consulted because the most impactful interventions should be among these 10 chief complaints. To maintain a reference point, however, we chose to group the remaining chief complaints in select figures (figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Predictors of ED LOS.

Adjusted by acuity, age, sex, arrival hour, ED provider, and chief complaint. LOS = length of stay.

Figure 4. Association of neurology consultation with LOS by chief complaint.

Adjusted by ED disposition, sex, age, acuity, arrival time of day, and ED physician. Cumulative difference = expected time saved if LOS with consult matched LOS without consult (hours) and is calculated by multiplying the number of consultations with the adjusted difference in LOS between patients with and without consultation. LOS = length of stay.

We determined the weights of predictors of neurology consultations using a logistic mixed methods model with the following categorical variables as fixed effects: age, sex, ESI score, chief complaint, and ED disposition. Time of patient arrival to the ED and time of ED provider arrival were included as random effects on the slope for each chief complaint. The coefficients of these random effects were then used as an estimation of the variability of consultation that can be attributable to time of ED arrival and ED provider.

We then evaluated the predictors of LOS using a linear mixed effects model with parameters similar to the model described for predictors of neurology consultation. The coefficients were used to estimate the association of LOS with ED disposition and with neurology consultation.

The fitglme function in MATLAB (version R2017a; MathWorks) was used to run the regressions for the mixed effects models.

Data availability

Any request for anonymized data from a qualified investigator would be subject to the discretion of the University of Pennsylvania IRB.

Results

The 10 most neurology-consulted chief complaints are shown in Table 1, which compares patient characteristics for those chief complaints for patients with and without neurology consultation. Of the 145,331 ED encounters analyzed over a 1-year period, 2,199 (13.1%) had a neurology consultation, and the most frequent chief complaints with neurology consultation were chief complaints with acute-onset neurologic deficit (12.1%), chief complaints with subacute neurologic deficit (11.2%), altered mental status (9.9%), seizures (8.1%), dizziness (7.4%), weakness (6.1%), headache (5.5%), numbness (4.8%), neurologic problem (3.6%), and fall (2.6%). Cumulatively, these 10 chief complaints accounted for 71% of those seen in the ED with a neurology consultation.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics among patients with most frequent 10 ED chief complaints

Compared with the patients without ED neurology consultation, the ones with ED neurology consultation were older (59.7 ± 17.9 years with consultation vs 52.3 ± 20.6 years without consultation), had higher acuity ESI scores (2.20 ± 0.60 vs 2.84 ± 0.67), higher rates of admission to the hospital (55.8% vs 18.8%), and higher rates of transfer to observation (10.1% vs 3.9%). They also had higher ED lengths of stay (mean ± SD: 11.3 ± 10.3 vs 7.3 ± 7.0 hours) overall and within the subgroup that was discharged home from the ED (15.3 ± 12.8 vs 6.6 ± 7.1 hours). Because the 2 groups had differences in multiple characteristics, subsequent analyses adjusted for age, acuity, and ED disposition.

A graphic of ED disposition for the top 10 chief complaints with neurology consultation is shown in figure 1. The encounters with the given chief complaint that did not result in neurology consultation in the ED are not included. Among the patients with ED neurology consult, the conditions with the highest chance of discharge after consultation were dizziness (77%), headache (76%), and numbness (69%).

Figure 1. Disposition of the top 10 chief complaints with a neurology consult.

All bars refer to the percent of encounters with the indicated disposition by chief complaint. Only encounters that resulted in neurology consultation in the ED are included. ED = emergency department.

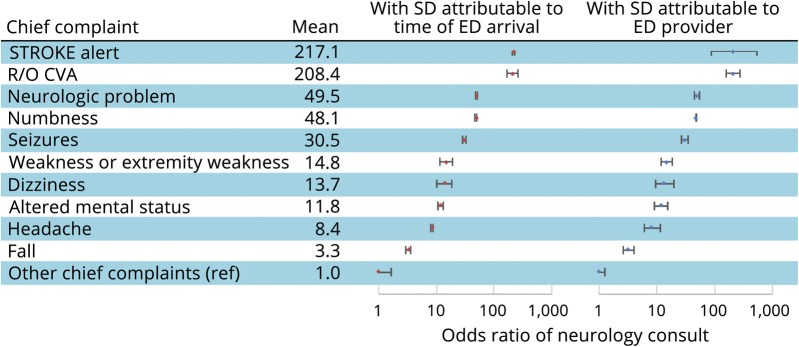

The influence of ED provider and time of ED arrival on the chance of consultation is shown in figure 2. In this analysis, ED provider and time of ED arrival were included as uncorrelated random effects for slope in a logistic mixed effects model. The SDs of the random effects parameters were plotted along with the odds ratio estimates for each of the chief complaints. The variability of consultation attributed to time of ED arrival, represented by the width of the error bars, was highest in the cases of chief complaints with subacute neurologic deficit, weakness or extremity weakness, and dizziness. The variability of consultation attributed to ED provider was highest for the cases of chief complaints with acute-onset neurologic deficit, dizziness, and headache.

Figure 2. Consultation variability by ED attending and by time of ED arrival.

Adjusted by acuity, ED disposition, and sex.

Compared with patients without neurology consult who were discharged home, the presence of a neurology consult was associated with 3.8-hour-longer mean ED LOS among admitted patients and 5.6-hour-longer mean ED LOS nonadmitted patients, after adjusting for acuity, age, sex, arrival hour, ED provider, and chief complaint (figure 3). The remaining chief complaints are grouped together and included as reference in this figure.

In the top 10 chief complaints with ED neurology consult, most (8 of 10) had an association between consultation and increased LOS (figure 4). Headache in particular had an average of 6.7-hour-longer ED LOS associated with consultation, followed by weakness or extremity weakness (4.4 hours) and numbness (4.1 hours). The largest estimated cumulative difference (number of patients with the specific consultation multiplied by estimated difference in LOS) belonged to headache, altered mental status, and seizures. These and the rest of the top 10 chief complaints accounted for about 80% of the cumulative differences associated with neurology consultation. There was also a statistically significant correlation overall among all conditions between neurology consultation and LOS (2.3 hours; 95% CI: 1.5–3.0).

The findings in each of the above analyses are summarized in table e-1 (links.lww.com/CPJ/A124). Chief complaints with the most overlap for these metrics included headache, dizziness, weakness or extremity weakness, and altered mental status.

Discussion

In an effort to mitigate ED overcrowding, institutions are turning to policies that set rules on time to consult.6,9,10 However, such interventions increase the burden on consultants and may even increase LOS elsewhere in the hospital.10 Another possible solution would be to reduce the dependence on consultants by using chief complaint–specific protocols, which can be safe and effective.11 However, development of these protocols is hindered by the need for consensus (ED providers must agree to use them, and neurologists must agree on their clinical validity), institutional support (specialty providers and clinics must agree to make capacity for studies or expedited appointments), and a clear understanding of the problem sizes and cost savings of such interventions. We addressed this last challenge by analyzing the variation in neurology consults in our EDs to begin the process of determining which consultations might be bypassed and which might be made more efficient with multidisciplinary protocols.

Similar to previous studies,7 we found that neurology consultation was associated with a longer ED LOS. Cumulatively, neurology consultation in the ED was associated with 5,702 bed-hours (238 bed-days) per year more compared with patients with similar chief complaints who did not have neurology consultation. What comprises the longer LOS? One study suggested that the time waiting for the start of the consult makes up nearly a quarter of the time,8 and the literature suggests that the most common reasons for delays in consultation are related to a “busy service.”12 Imaging is yet another important contributor. However, in a sampling of cases, we discovered it was difficult to characterize this further, given variable sequence (for example, in some cases, consultants preferred imaging before consult, whereas some preferred imaging after consult), concurrency, and imperfect documentation (i.e., the time a neurologist begins and ends thinking about a patient is not clear).

On what complaints should EDs focus their efforts? We identified the most common types of neurology consultations, the association of these consults with ED LOS, and the variability of these consults by ED provider and by time of ED arrival. We posit that variability in consultation may represent varying thresholds in the willingness to inconvenience clinicians after hours and differing case mix at different times of day. High temporal and provider-based variability may suggest chief complaints for which ED providers can be nudged toward offering expedited outpatient follow-up rather than ED consultation. Yet another indicator of opportunity is a condition with high percentages of ED discharge home after consult.

By consolidating these indicators (table e-1, links.lww.com/CPJ/A124), we found several chief complaints that overlapped, suggesting areas of greatest opportunity: these included headache, dizziness, and weakness or extremity weakness. Protocols can help decide when consultation or imaging is necessary or when admission is appropriate. For example, HINTS13 is a protocol for dizziness, particularly vertigo, that can help decide when imaging is necessary. We know that providers with low threshold for testing, such as an MRI to rule out stroke, perform more testing that result in longer lengths of stay.14

We approached the issue of ED overcrowding and nonoptimal consultation by investigating consult utilization, influence on ED LOS, and potential areas to streamline, defer, or optimize consultation. Hospitals might begin to reduce ED LOS by addressing chief complaints individually, starting with those associated with high LOS burden, high likelihood of discharge, and temporal/ED provider variability. Next steps include reviewing the complaint-specific pathways that have been implemented at other institutions and gathering consensus among our own providers.

This analysis is limited by its retrospective nature, and, consequently, causal conclusions cannot be made. Moreover, although our analysis adjusts for illness severity, there are likely features of illness or symptom severity that are not fully captured by either the chief complaint or the ESI, and these might be confounders that influence both ED LOS and the likelihood of neurology consultation. Similarly, we used chief complaint as a proxy of the reason for consultation, which does not capture other reasons for neurology consult. Because a triage nurse assigns chief complaints, the documented chief complaints are not as accurate as the final diagnoses. However, we think that this scenario mimics the situation in most EDs and the usage of a data element assigned early in the encounter here leave open the possibility that a patient can be initiated on a pathway before a completed physician evaluation.

Furthermore, this study was performed at 3 urban teaching hospitals. We believe that this is appropriate because ED overcrowding disproportionately affects urban medical centers, many of which happen to be academic centers.5 Nonetheless, we recognize that this may not completely represent or generalize to the issues faced by all hospitals around the country.

In this study, we used variability of consultation as an indicator for areas where a consultation may not be necessary. Variability is in part due to ED provider comfort and cultural factors at various medical centers. However, for how many of these cases neurology consultation is warranted is difficult for us to say, given the uniqueness of each case.

Finally, this study does not describe any attempt at implementing a pathway. The results of our suggested intervention remain an area for future study, as does the quantification of the operational benefit of standardizing protocols for our EDs.

The role of the neurologist must shift toward evaluating and identifying patients with acute neurologic deficits who are candidates for acute interventions and away from nonurgent consultations. Concurrently, EDs are facing issues with overcrowding, to which subspecialty consultation contributes. We used a systematic approach to characterize ED consultation utilization and quantify its impact on ED LOS. In particular, headache, dizziness, and weakness or extremity weakness are chief complaints that had high prevalence, significant associations with ED LOS, and high variability of consult depending on the ED provider and the time of presentation. These conditions may benefit from protocolized pathways, which can help ED providers triage some cases to outpatient follow-up or order testing while waiting for consultation. To carry this work out to its full potential, clinical expertise and iterative studies would be necessary to design these protocols, obtain consensus, and train providers to use them.

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Trzeciak S, Rivers EP. Emergency department overcrowding in the United States: an emerging threat to patient safety and public health. Emerg Med J 2003;20:402–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan AF, Espinola JA, Chen DK, Sheils CR, Brown FM. United States emergency department openings, closures, and annual visit volumes: 2001 to 2011. Ann Emerg Med 2014;64(4 suppl 1):S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy ML, Zeger SL, Ding R, et al. Crowding delays treatment and lengthens emergency department length of stay, even among high-acuity patients. Ann Emerg Med 2009;54:492–503.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon P, Steiner I, Reinhardt G. Analysis of factors influencing length of stay in the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med 2003;5:155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee RS, Woods R, Bullard M, Holroyd BR, Rowe BH. Consultations in the emergency department: a systematic review of the literature. Emerg Med J 2008;25:4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho SJ, Jeong J, Han S, et al. Decreased emergency department length of stay by application of a computerized consultation management system. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Linden MC, van den Brand CL, van den Wijngaard IR, de Beaufort RAY, van der Linden N, Jellema K. A dedicated neurologist at the emergency department during out-of-office hours decreases patients' length of stay and admission percentages. J Neurol 2018;265:535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brick C, Lowes J, Lovstrom L, et al. The impact of consultation on length of stay in tertiary care emergency departments. Emerg Med J 2014;31:134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner B, Holmes T, Simpson D, Smith CW, Reece EA. Reducing specialty consultation times in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2004;11:463. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geskey JM, Geeting G, West C, Hollenbeak CS. Improved physician consult response times in an academic emergency department after implementation of an institutional guideline. J Emerg Med 2013;44:999–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutto L, Meineri P, Melchio R, et al. Nontraumatic headaches in the emergency department: evaluation of a clinical pathway. Headache 2009;49:1174–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee PA, Rowe BH, Innes G, et al. Assessment of consultation impact on emergency department operations through novel metrics of responsiveness and decision-making efficiency. CJEM 2014;16:185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh Y-H, Newman-Toker DE. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome. Stroke 2009;40:3504–3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kocher KE, Meurer WJ, Desmond JS, Nallamothu BK. Effect of testing and treatment on emergency department length of stay using a national database. Acad Emerg Med 2012;19:525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Any request for anonymized data from a qualified investigator would be subject to the discretion of the University of Pennsylvania IRB.