Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) is one of the most significant swine diseases. However, the phylogenetic and genomic recombination properties of the PRRS virus (PRRSV) have not been completely elucidated. In this study, we systematically compared differences in the lineage distribution, recombination, NSP2 polymorphisms, and evolutionary dynamics between North American (NA)-type PRRSVs in China and in the United States. Strikingly, we found high frequency of interlineage recombination hot spots in nonstructural protein 9 (NSP9) and in the GP2 to GP3 region. Also, intralineage recombination hot spots were scattered across the genome between Chinese and US strains. Furthermore, we proposed novel methods based on NSP2 indel patterns for the classification of PRRSVs. Evolutionary dynamics analysis revealed that NADC30-like PRRSVs are undergoing a decrease in population genetic diversity, suggesting that a dominant population may occur and cause an outbreak. Our findings offer important insights into the recombination of PRRSVs and suggest the need for coordinated international epidemiological investigations.

KEYWORDS: deletion, interlineage, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, recombination hotspots

ABSTRACT

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), an important pathogen that affects the pig industry, is a highly genetically diverse RNA virus. However, the phylogenetic and genomic recombination properties of this virus have not been completely elucidated. In this study, comparative analyses of all available genomic sequences of North American (NA)-type PRRSVs (n = 355, including 138 PRRSV genomes sequenced in this study) in China and the United States during 2014–2018 revealed a high frequency of interlineage recombination hot spots in nonstructural protein 9 (NSP9) and the GP2 to GP3 regions. Lineage 1 (L1) PRRSV was found to be susceptible to recombination among PRRSVs both in China and the United States. The recombinant major parent between the 1991–2013 data and the 2014–2018 data showed a trend from complex to simple. The major recombination pattern changed from an L8 to L1 backbone during 2014–2018 for Chinese PRRSVs, whereas L1 was always the major backbone for US PRRSVs. Intralineage recombination hot spots were not as concentrated as interlineage recombination hot spots. In the two main clades with differential diversity in L1, NADC30-like PRRSVs are undergoing a decrease in population genetic diversity, NADC34-like PRRSVs have been relatively stable in population genetic diversity for years. Systematic analyses of insertion and deletion (indel) polymorphisms of NSP2 divided PRRSVs into 25 patterns, which could generate novel references for the classification of PRRSVs. The results of this study contribute to a deeper understanding of the recombination of PRRSVs and indicate the need for coordinated epidemiological investigations among countries.

IMPORTANCE Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) is one of the most significant swine diseases. However, the phylogenetic and genomic recombination properties of the PRRS virus (PRRSV) have not been completely elucidated. In this study, we systematically compared differences in the lineage distribution, recombination, NSP2 polymorphisms, and evolutionary dynamics between North American (NA)-type PRRSVs in China and in the United States. Strikingly, we found high frequency of interlineage recombination hot spots in nonstructural protein 9 (NSP9) and in the GP2 to GP3 region. Also, intralineage recombination hot spots were scattered across the genome between Chinese and US strains. Furthermore, we proposed novel methods based on NSP2 indel patterns for the classification of PRRSVs. Evolutionary dynamics analysis revealed that NADC30-like PRRSVs are undergoing a decrease in population genetic diversity, suggesting that a dominant population may occur and cause an outbreak. Our findings offer important insights into the recombination of PRRSVs and suggest the need for coordinated international epidemiological investigations.

INTRODUCTION

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS), one of the most important diseases that affects the global pig industry, was first recognized in the United States in 1987 (1). In countries such as China and the United States, where the pork industry yields approximately 60% of the world’s pig production, PRRS causes remarkable economic losses (2, 3). The causative agent, the PRRS virus (PRRSV), is an enveloped, single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus. Its genome is approximately 15 kb in length and encodes at least 10 open reading frames (ORFs): ORF1a, ORF1b, ORF2a, ORF2b, ORF3, ORF4, ORF5a, ORF5, ORF6, and ORF7 (4). ORF1a and ORF1b encode viral nonstructural proteins (NSPs) (5), whereas ORF2a, ORF2b, ORF5a, and ORF3 to -7 encode the structural proteins GP2, E, ORF5a, GP3, GP4, GP5, M, and N (4, 6). PRRSV is classified into two genotypes, the European type (EU-type, prototype strain Lelystad virus) and North American type (NA-type, prototype strain VR-2332 virus), which share only approximately 60% similarity at the nucleotide level (7).

As RNA-dependent RNA polymerase lacks the 3′ to 5′ exonuclease proofreading ability, the mutation rate of RNA viruses is high (8). The calculated rate of PRRSV nucleotide substitutions, 4.7 × 10−2 to 9.8 × 10−2/site/year, is the highest reported for an RNA virus (9). The PRRSV ORF5 gene exhibits high genetic diversity and is widely used for phylogenetic analyses (10). Based on genetic relationships among ORF5 sequences, NA-type PRRSVs were divided into nine lineages, lineage 1 to lineage 9 (L1 to L9) (11). Deletion is often observed in PRRSVs; for example, NSP2 can tolerate amino acid deletions and foreign gene insertions (12), such as the linked 30-amino-acid (aa) discontinuous deletion in NSP2 of the highly pathogenic PRRSV strain in China (13), the linked 131-aa discontinuous deletion in NSP2 of MN184- or NADC30-like PRRSV (14), and the 100-aa continuous deletion in NSP2 of NADC34-like PRRSV (15). Moreover, recombination events were detected between wild-type PRRSV strains and also occurred between wild-type PRRSVs and modified live virus (MLV) vaccine strains (16, 17). Recombination not only results in the generation of novel PRRSV genotypes but is also associated with increases in virulence (16). Recombination breakpoints are relatively random; however, data analysis may identify possible shared recombination regions in independent recombination events. Furthermore, dominant sequences that promote recombination may be found, which is of great significance for us to understand the recombination mechanism of PRRSV.

Over the past 10 years, China has imported many breeding pigs from the United States, Canada, and European countries. In particular, the largest number came from the United States. As the two leading pig-raising countries, China and the United States have contributed the majority of NA-type PRRSV genomic sequences to GenBank. Previous PRRSV studies lacked comparisons of prevalent features and genetic variation between Chinese and the US strains. The objective of this study was to compare the genomes of NA-type PRRSV collected from China and the United States during 2014–2018 and systematically analyze their epidemic distribution, recombination, NSP2 polymorphisms, and molecular evolutionary dynamics.

RESULTS

Genomic surveillance of PRRSV in China and the United States.

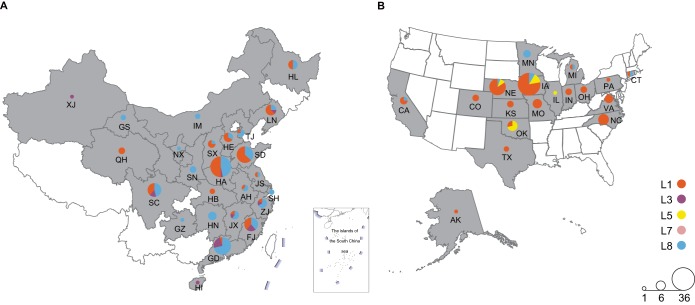

To provide insight into NA-type PRRSVs in China and the United States from 2014 to 2018, the genomes of positive PRRSV strains from these countries were sequenced by next-generation sequencing (NGS) and the Sanger method. The genome sizes of 138 NA-type PRRSV strains (United States, 102; China, 36) ranged from 14,643 to 15,526 nucleotides. The sequences of all strains (138/138 strains [100%]) included all ORFs, and 66/138 strains (48%) had complete genome sequences including the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions. In addition, complete genome sequences of 217 NA-type PRRSV strains (United States, 84; China, 133) were downloaded from the GenBank database. Collectively, the sequences used in this study were sampled from 25 provinces of China and 18 states of the United States (Fig. 1). Strains from Henan, Guangdong, and Shandong accounted for 18%, 12%, and 12% of the Chinese PRRSVs, respectively. In the United States, the percentages of strains from Iowa, Nebraska, and North Carolina were 19%, 10%, and 7%, respectively. According to the classification criteria of PRRSV lineages (intralineage diversity levels of <11%) by Shi et al. (11), the 138 NA-type PRRSV strains sequenced in the present study belong to lineage 1 (L1), lineage 3 (L3), lineage 5 (L5), lineage 7 (L7), and lineage 8 (L8).

FIG 1.

Geographical distribution of NA-type PRRSVs in China (A) and the United States (B). The different colors indicate the different lineages, and the sizes of the circles represent the numbers of PRRSVs. The number of strains of each lineage was counted, and their relative proportions are illustrated by pie charts in each province/state. Information for 25 provinces of China and 18 states of the United States are presented as follows. AH, Anhui (n = 3); FJ, Fujian (n = 13); GS, Gansu (n = 2); GD, Guangdong (n = 21); GZ, Guizhou (n = 1); HI, Hainan (n = 1); HE, Hebei (n = 6); HL, Heilongjiang (n = 6); HA, Henan (n = 30); HB, Hubei (n = 2); HN, Hunan (n = 5); IM, Inner Mongolia (n = 2); JS, Jiangsu (n =2); JX, Jiangxi (n = 6); LN, Liaoning (n = 7); NX, Ningxia (n = 1); QH, Qinghai (n = 3); SN, Shaanxi (n = 3); SD, Shandong (n = 19); SH, Shanghai (n = 2); SX, Shanxi (n = 4); SC, Sichuan (n = 13); TJ, Tianjin (n = 4); XJ, Xinjiang (n = 1); ZJ, Zhejiang (n = 5); AR, Arkansas (n = 1); CA, California (n = 4); CO, Colorado (n = 3); CT, Connecticut (n = 2); IL, Illinois (n = 1); ID, Indiana (n = 3); IA, Iowa (n = 36); KS, Kansas (n = 3); MI, Michigan (n = 2); MN, Minnesota (n = 4); MO, Missouri (n = 6); NE, Nebraska (n = 19); NC, North Carolina (n = 8); OH, Ohio (n = 3); OK, Oklahoma (n = 7); PA, Pennsylvania (n = 1); TX, Texas (n = 2); VA, Virginia (n = 5).

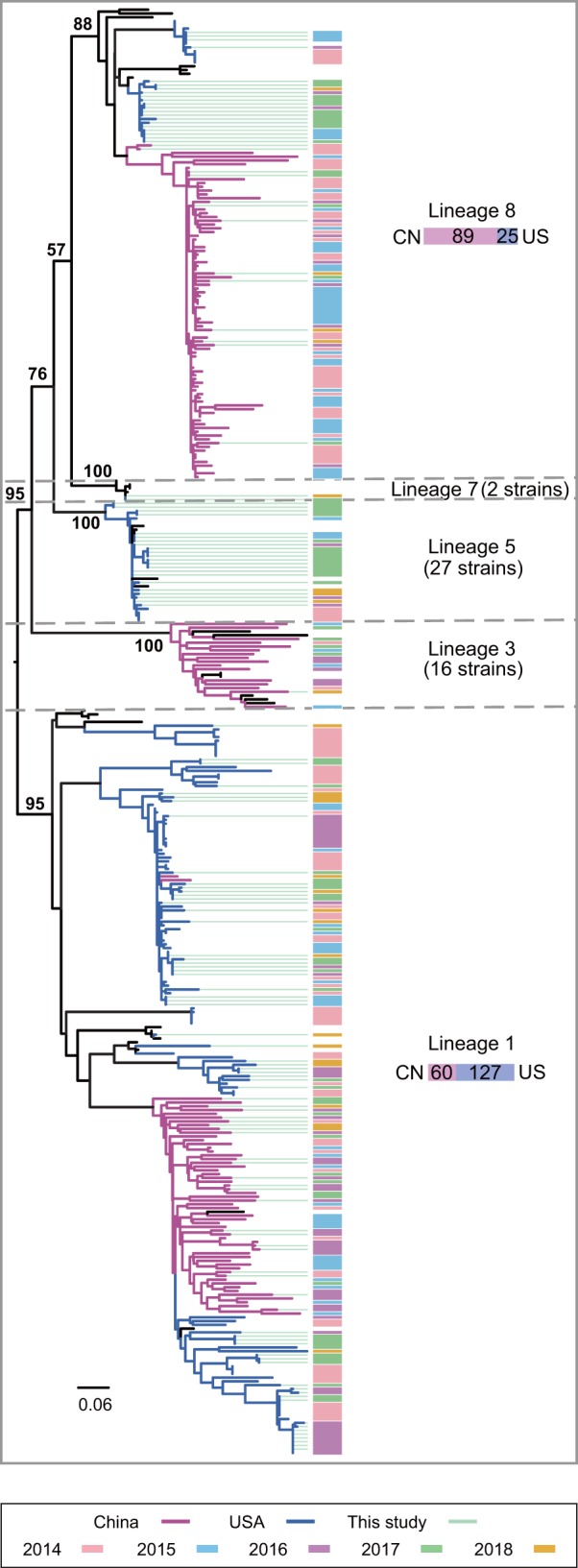

Phylogenetics and lineage specification of PRRSV.

Based on the maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis of 346 (after removing 9 recombinant strains) ORF5 nucleotide alignments, PRRSVs sampled between 2014 and 2018 fell into five lineages (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), including L1 (n = 187), L3 (n = 16), L5 (n = 27), L7 (n = 2), and L8 (n = 114). Notably, L1 and L8 were predominant in both China and the United States. Lineage 1 was further separated into six sublineages (L1.1 to L1.6). Of the entire lineage 1, 5%, 35%, 3%, 1%, 7%, and 50% were classified into L1.1 to L1.6, respectively (Fig. S1 and Table S9).

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on ORF5 of PRRSVs. The branches in purple represent the Chinese strains and those in blue represent strains from the United States. Green lines behind the tree denote viruses sequenced in this study. The time of strain isolation is shown in different colored bars, as indicated in the legend.

In China, approximately 53% of all Chinese sequences belonged to L8. In contrast, approximately 36% belonged to L1. Lastly, 10% of Chinese sequences belonged to L3. Multilineage coexistence was found in several provinces; for example, L1, L3, and L8 PRRSVs coexisted in Henan, Guangdong, Sichuan, Fujian, and Jiangxi provinces (Fig. 1A).

In the United States, L1 was the most prevalent and comprised approximately 68% (127/186) of all sequences, which was followed by L5 (15%) and L8 (13%). In addition, two strains were classified as L7 (MN073128 and MN073129). The distribution of PRRSV lineages in Iowa and Nebraska was more complex with the coexistence of three lineages (L1, L5, and L8), whereas only one or two lineages existed in other states (Fig. 1B).

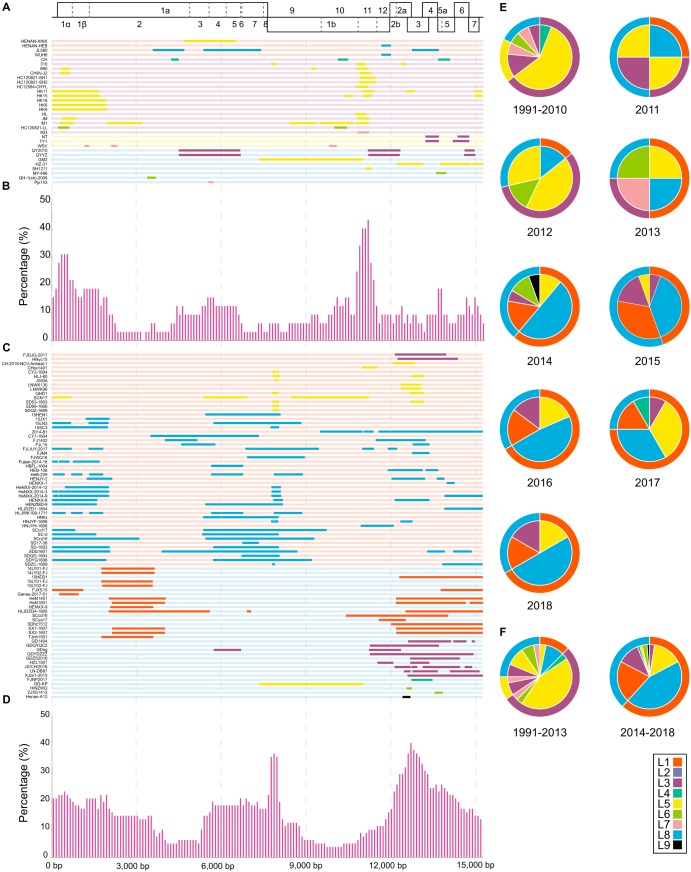

Interlineage PRRSV recombination in China.

The locations of recombination breakpoints were determined according to the positions of VR-2332, the prototype NA-type PRRSV strain (Fig. 3A and C and Table S2). The recombination frequency (the number of recombinations that occurred at a specific site in proportion to the total recombination number) of each position was calculated; a recombination hot spot was defined by a position with a recombination percentage higher than 25% (Fig. 3B and D). Recombination hot spots ranged from nucleotide positions of approximately 7,900 to 8,100 (in the NSP9 region, which encodes RdRp) and 12,400 to 13,500 (in the GP2 to GP3 region) for Chinese PRRSVs detected from 2014 to 2018 (Fig. 3D). However, for strains detected from 1991 to 2013, high-frequency recombination regions were mainly found in the locations of 300 to 600 (in the NSP1 region) and 11,100 to 11,400 (in the NSP11 region) nucleotide positions relative to the VR-2332 genome, which were not the same as those detected in 2014–2018 (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Maps of parental lineages of genomes and interlineage recombination patterns in China from 1991 to 2018. (Top) Full-length genome structure, with reference to VR-2332, in which the positions and boundaries of the major ORFs and NSPs within ORF1a and ORF1b are shown. Gray vertical dashed lines spaced 3,000 bp apart were used to locate the recombination breakpoint positions and the x axis positions of the histograms. The different colors depict different PRRSVs lineages. (A) A map of parental lineages of genomes from 1991 to 2013. The name of each strain is displayed on the left, and the corresponding full-length genome of the major parent is displayed in different lineage colors on the right. The change in color of the major parent means that the fragment had been replaced by a minor parent, indicating the presence of a recombinant. (B) The proportions of recombinant genomes identified with minor parent sequences in China from 1991 to 2013. The x axis represents the PRRSV genome position, and the y axis represents the number of recombinations that occurred at a specific site in proportion to the total number of recombinants in a sliding window (per 100 nucleotide bases) centered on that position in the x axis. (C) A map of parental lineages of genomes from 2014 to 2018. (D) The proportions of recombinant genomes identified with minor parent sequences in China during 2014–2018. (E) Major and minor parental strain contributors in recombinants observed during various time periods in 1991–2018. The major parent is shown on the outer ring, and the corresponding minor parent is shown in the pie chart. (F) Major and minor parental strain contributors in recombinants observed between 1991–2013 and 2014–2018.

To explore changes in the interlineage recombination of PRRSVs in China, the major and minor parental strain contributors in recombinants were calculated from 1991 to 2018. In Fig. 3E, the major parents of the recombinants from 1991 to 2013 and 2014 to 2018 showed a trend from complex (L1, L3, L5, and L8) to simple (L1 and L8), respectively. Moreover, the proportion of recombination based on the L1 backbone increased annually, from 44% in 2015 to 75% in 2017. In contrast, the proportion of recombination based on the L8 backbone declined annually: 56% in 2015, 33% in 2016, and 25% in 2017. From 1991 to 2013, the recombinants with L3 PRRSVs as the major parents and L5 PRRSVs as minor parents accounted for the majority (Fig. 3F). Comparatively, during 2014–2018, the major interlineage recombination patterns observed were L1 PRRSVs (major parent) and L8 PRRSVs (minor parent), and L8 PRRSVs (major parent) and L1 PRRSVs (minor parent).

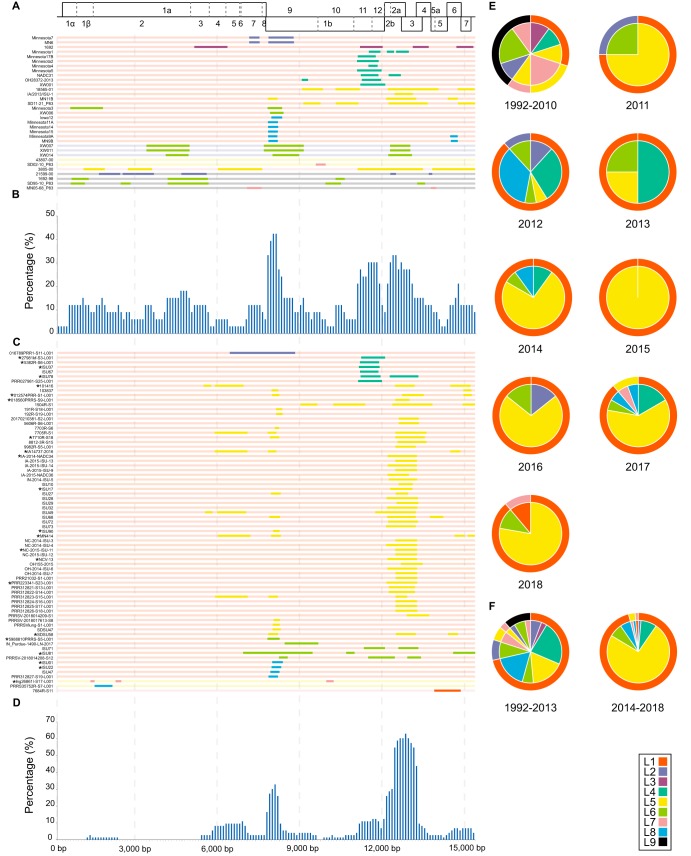

Comparison of interlineage recombination between China and the United States.

The major and minor parental strains of recombinant PRRSVs in the United States were also determined (Fig. 4 and Table S3). Similar to those detected in China, the recombination hot spots in the United States also ranged from nucleotides 7,900 to 8,200 (in the NSP9 region) and 12,200 to 13,300 nucleotides (in the GP2 to GP3 region) during 2014–2018 (Fig. 4D). However, for PRRSV detected during 1992–2013, high-frequency recombination regions were mainly distributed in the 7,800 to 8,200, 11,500 to 11,800, and 12,300 to 13,000 nucleotide regions (Fig. 4B). The high-frequency recombination regions were located in NSP9, NSP11 to -12, and GP2, which were slightly different from those in 2014–2018. Additionally, the lengths of PRRSV recombinant fragments of US PRRSVs were shorter than those of Chinese PRRSVs, but the recombination hot spots of the two were similar, and both were located in the NSP9 and GP2 to GP3 regions during 2014–2018.

FIG 4.

Maps of parental lineages of genomes and interlineage recombination patterns in the United States from 1992 to 2018. (Top) Full-length genome structure, with reference to VR-2332, in which the positions and boundaries of the major ORFs and NSPs within ORF1a and ORF1b are shown. Gray vertical dashed lines spaced 3,000 bp apart were used to locate the recombination breakpoint positions and the x axis positions of the histograms. The different colors depict different PRRSV lineages. (A) A map of parental lineages of genomes from 1992 to 2013. The name of each strain is displayed on the left, and the corresponding full-length genome of the major parent is displayed in different lineage colors on the right. The change in color of the major parent means that the fragment had been replaced by a minor parent, indicating the presence of a recombinant. (B) The proportions of recombinant genomes identified with minor parent sequences in the United States from 1992 to 2013. The x axis represents the PRRSV genome position, and the y axis represents the number of recombinations that occurred at a specific site in proportion to the total number of recombinants in a sliding window (per 100 nucleotide bases) centered on that position in the x axis. (C) A map of parental lineages of genomes from 2014 to 2018. The following groups were considered the same recombination events, and only the earliest strain of each group after exclusion of the same recombination events is displayed with an asterisk: 1, 27981kf-S3-L001 and PRR027982-S26-L001; 2, 5382R-S6-L001, 5381R-S5-L001, and 5383R-S7-L001; 3, ISU37, ISU39, and ISU40; 4, ISU78, ISU94, ISU95, ISU96, and ISU97; 5, 101416, 109560, and 21675; 6, 012574PRR-S1-L001 and 012574VI-S2-L001; 7, 018560PRRS-S9-L001, 018561PRRS-S10-L001, 1923R-S1-L001, 1924R-S2-L001, and 9337R-S4-L001; 8, 7710R-S18, 0752R-S4, and 7498-S10; 9, IA14737-2016, 014737Fib-S5-L001, 014737lu1A-S1-L001, 014737lu2A-S2-L001, 014737luB-S3-L001, 014737luC-S4-L001, 014737Ton-S6-L001, br42321BC-S13-L001, and PRR41505-S4-L001; 10, IA-2014-NADC34, IA-2014-ISU-8, IA-2015-ISU-10, and IA-2015-NADC35; 11, ISU17 and ISU18; 12, ISU90 and ISU91; 13, MN414, PRR027983-S27-L001, and PRR027984-S28-L001; 14, NC-2015-ISU-11 and 2385R-S13; 15, NCV-13, brian27950-S16-L001, NCV-16, NCV-17, NCV-21, NCV-23, NCV-24, NCV-25, and NCV-26; 16, PRR223341-S23-L001 and PRR223343-S24-L001; 17, SDSU58 and SDSU62; 18, 5988810PRRS-S5-L001 and 52335PRRS-S10-L001; 19, ISU81, ISU82, ISU84, ISU86, and ISU87; 20, ISU01, ISU04, ISU05, ISU06, and ISU07; 21, ISU22, ISU23, ISU24, and ISU25; 22, Ing26861I-S17-L001 and Ing26862I-S18-L001. (D) The proportions of recombinant genomes identified with minor parent sequences in the United States from 2014 to 2018. (E) Major and minor parental strain contributors in recombinants observed during various time periods in 1992–2018. The major parent is shown on the outer ring, and the corresponding minor parent is shown in the pie chart. (F) Major and minor parental strain contributors in recombinants observed between 1992–2013 and 2014–2018.

The major parents of the recombinants were L1, L5, L7, and L9 from 1992 to 2010; however, L1 has been the predominant major parent in recombination events in the United States since 2011 (Fig. 4E). Recombinants in the United States evolved from a complex pattern of L1+L4, L1+L5, and L1+L8 during 1991–2013, into a singular pattern dominated by L1+L5 during 2014–2018 (Fig. 4F). In general, the data reflected that L1 played an increasingly important role in the evolutionary history of recombination events in China and the United States from 1991–2013 to 2014–2018. However, the Chinese recombination patterns were mainly L1+L8 and L8+L1, whereas the major recombination pattern of the United States was L1+L5.

The frequencies of interlineage recombination (the percentage of recombinants from the total number of strains), were classified according to the following factors: 1991–2013 versus 2014–2018 data, China versus the United States, strains downloaded from GenBank versus strains sequenced (see Table S8). Recombination frequency was increased in 2014–2018 (43%) compared to 19% in 1991–2013. The recombination frequency of PRRSV strains that were sequenced in the study (43%) was similar to that of NA-type PRRSVs strains downloaded from GenBank (44%) in 2014–2018. For NA-type PRRSVs during 2014–2018, the integral interlineage recombination frequency of Chinese strains (approximately 48%) was higher than that of US strains (approximately 39%). Furthermore, in the 2014–2018 data, the interlineage recombination frequencies of L1 and L8, which were the epidemic major parents of Chinese recombination events, were approximately 79% and 29%, respectively, whereas in the United States, the recombination frequency of L1, which was the dominant major parent, was approximately 54%.

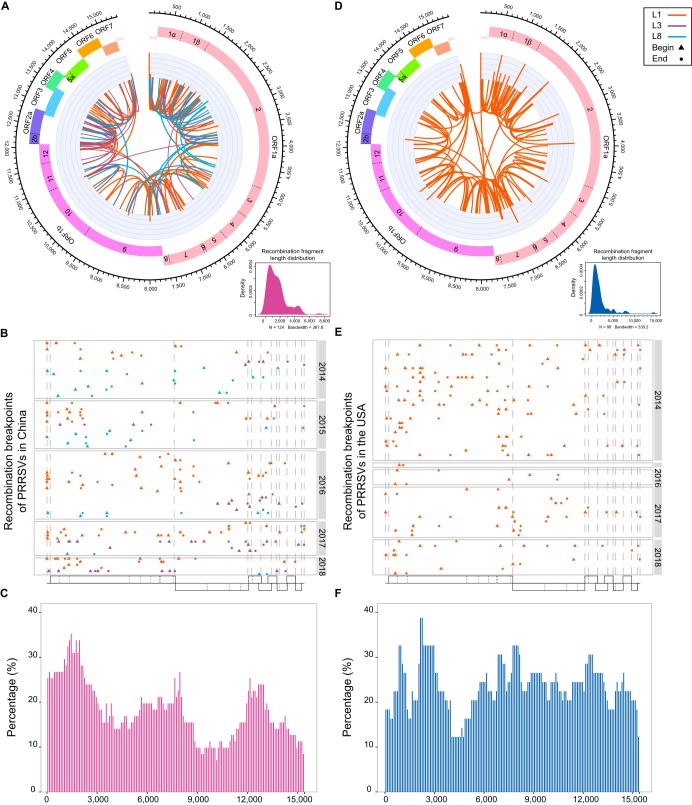

Intralineage recombination of PRRSVs during 2014–2018.

Intralineage recombination in both countries was also detected (see Table S3). Of 71 recombinants identified from 169 Chinese strains, recombination events occurred frequently in every lineage, and the recombination fragments were mainly 1,000 to 2,000 nucleotides long (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, high-frequency recombination regions of Chinese PRRSVs in intralineage recombination showed a similar fluctuation trend genome wide as that in interlineage recombination during 2014–2018 (Fig. 3D and 5C). Recombination frequencies were slightly lower than those of interlineage recombination at 59% (37/63) for L1, 81% (13/16) for L3, and 23% (21/90) for L8.

FIG 5.

Comparison of intralineage recombination between China and the United States in 2014–2018. Different lineages are shown in different colors, consistent with the previous description. The genome positions represent positions in the full-length genome alignment related to the VR-2332 strain. (A to C) Intralineage recombinations of Chinese PRRSVs. (D to F) Intralineage recombinations of PRRSVs in the United States. (A and D) Overview of intralineage recombinations. Linkages represent recombination events, connecting the beginning and the ending position of each event; histograms represent recombination breakpoints that occurred more than once; the density map in the lower right corner represents the size distribution of the recombinant fragment. (B and E) Breakpoint distributions of intralineage recombinations in each year. Each box represents a different year; breakpoints on each horizontal line originate from one recombinant, and recombination breakpoints are shown as different shapes, with the starting position as a triangle and the ending position as a dot. The vertical dotted lines in the dot diagrams represent the starting and ending positions of ORFs, which correspond to the genome bar charts below. (C and F) Bar charts showing the proportions of recombinant genomes identified with minor parent sequences in China and in the United States from 2014 to 2018. The x axis represents the PRRSV genome position, and the y axis represents the number of recombinations that occurred at a specific site in proportion to the total number of recombinants in a sliding window (per 100 nucleotide bases) centered on that position in the x axis.

For the 186 US strains, 49 recombinants were detected. All 49 recombination events in the United States occurred in L1 PRRSVs (Fig. 5D and E). There were no recombinants in L5 and L8. The overall recombination frequency (the percentage of recombinants from the total number of strains) for China (42% [71/169]) was much higher than that for the United States (26% [49/186]).

Recombination breakpoints were distributed throughout the whole genome, and there was no positional preference (Fig. 5B and E). The genomic regions with recombination percentages greater than 25% were defined as recombination hot spots. In China, the intralineage recombination hot spots were mainly concentrated in 1 to 2,300, 7,600 to 7,700, 7,900 to 8,000, and 12,100 to 12,200 nucleotide (nt) regions (Fig. 5A to C), located in NSP1 to NSP2, NSP8, NSP9, and GP2, respectively. In contrast, in the United States, hot spots were distributed in almost all nonstructural proteins (NSP1, -2, -4, and -6 to -10), as well as GP2 to GP3 and M (Fig. 5D to F).

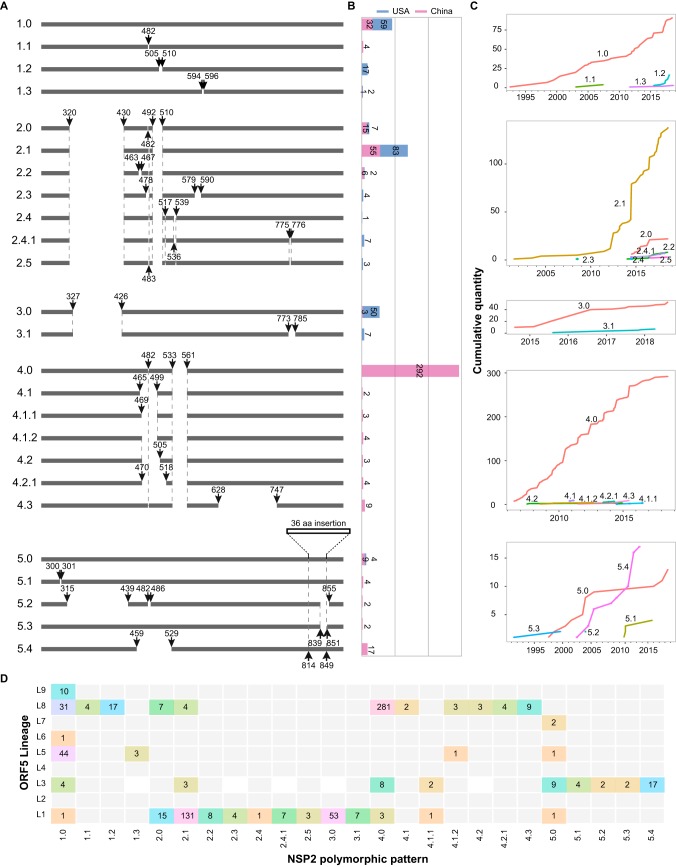

Patterns of NSP2 polymorphisms.

To systematically analyze NSP2 indel pattern (PNSP2) in PRRSVs, 713 NSP2 full-length sequences (from complete genome sequences of available NA-type PRRSVs from 1991 to 2018) were divided into 5 large patterns (PNSP21 to PNSP25) and 25 subdivided patterns according to the indel framework of amino acids (aa) (see Table S6). PNSP21 consisted of 115 strains (Fig. 6B), in which no indel pattern was identified in PNSP21.0 (Fig. 6A), including VR-2332, PNSP21.1 (1 aa deleted at 482), PNSP21.2 (6 aa deleted at 505 to 510), and PNSP21.3 (3 aa deleted at 594 to 596) according to small deletions in the background of 1.0. PNSP22 had the deletion feature of “111 + 1+19” and contained 183 strains, including 76 from China and 107 from the United States (Fig. 6A and B). There were 60 strains in PNSP23, which contained the 100-aa deletion at 327 to 426; an additional 13-aa deletion at position 773 to 785 was found in several strains, which were subsequently grouped as PNSP23.1. PNSP24 displayed the deletion feature of “1 + 29,” which is a unique characteristic of highly pathogenic PRRSV. This category contained 317 strains, all from China (Fig. 6B), with most belonging to the L8 lineage (Fig. 6D). In addition, 38 strains with a 36-aa insertion at 814 were grouped as PNSP25. Most of these were identified in Taiwan and Hong Kong. Both PNSP21.0 and PNSP25.3 emerged in the early 1990s; however, PNSP25.3 disappeared soon after emerging and PNSP21.0 has persisted to date. Both PNSP22.1 and PNSP24.0 displayed processes of sustained and rapid growth from the time of their emergence (Fig. 6C). In most cases, individual NSP2 polymorphic patterns corresponded to a specific ORF5 lineage; for example, PNSP22 and -3 PRRSVs were mainly ORF5 L1, PNSP24 PRRSVs were mainly ORF5 L8, and most of PNSP25 PRRSVs were in ORF5 L3. However, there were also strains in these four patterns scattered across other ORF5 lineages, and PNSP21 was distributed in multiple ORF5 lineages (Fig. 6D). Overall, there was not a single ORF5 lineage (9 phylogenetic lineages) which corresponded to each NSP2 polymorphic pattern (25 polymorphic patterns of NSP2).

FIG 6.

Insertion and deletion patterns of NSP2 in PRRSV. (A) Systematic classification of NSP2 polymorphic patterns. There are 5 large patterns and 25 subdivided groups, and the location of each NSP2 indel pattern is marked. The positions marked in the figure represent positions of the NSP2 amino acid sequence and refer to the position of VR-2332. (B) Strain numbers of each pattern and comparison between China and the United States. Bars in blue represent the numbers of US strains, and the bars in red represent the numbers of Chinese strains. (C) Cumulative curve of each pattern over time. The x axis represents the year, the y axis represents the total number of strains up to that year, and each pattern is shown in a different color and marked on the graph. (D) Relationship between ORF5 lineage and NSP2 polymorphic pattern. The horizontal axis shows the 25 polymorphic patterns of NSP2 defined in panel A, the vertical axis shows the 9 phylogenetic lineages of ORF5 described by Shi et al. (11), and the numbers in the heat map identify the numbers of strains.

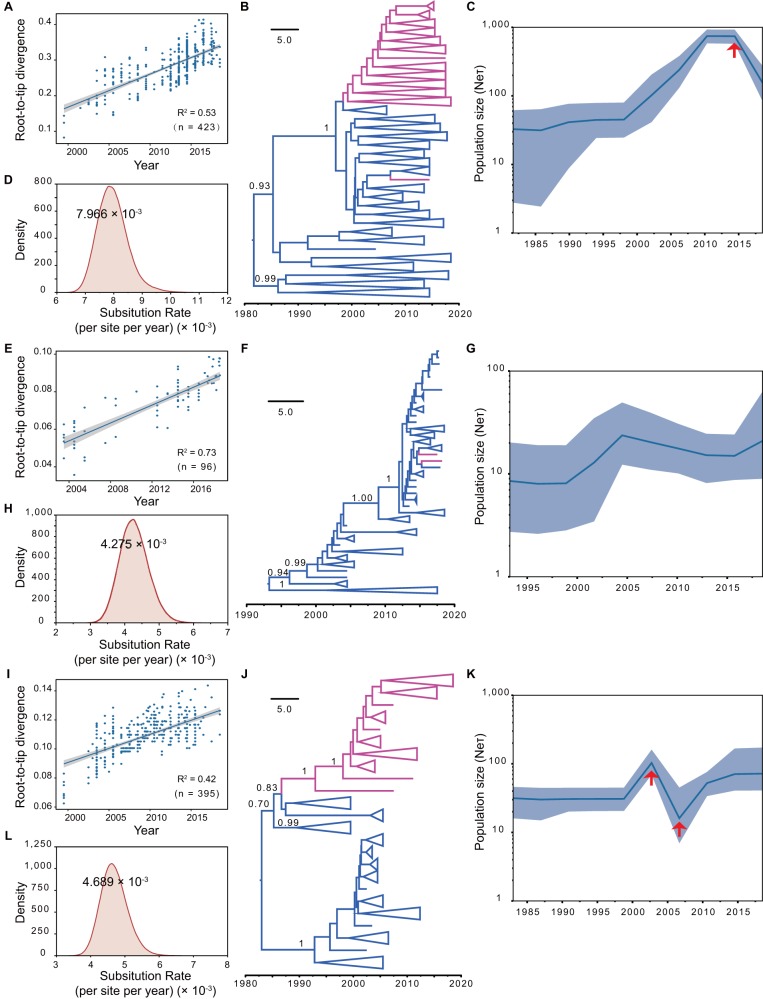

Evolutionary dynamics of L1 and L8 PRRSVs.

To explore the spatiotemporal relationships of L1 and L8, we performed phylogeographic analysis using BEAST2. L1 was separated into two clusters, one comprising NADC30-like PRRSVs consisting of 423 ORF5 sequences from 1999 to 2018 and the other contained NADC34-like PRRSVs, including 96 ORF5 sequences from 2003 to 2018. L8 contained 395 ORF5 sequences from 1999 to 2018 (Fig. 7 and Fig. S2).

FIG 7.

Bayesian spatiotemporal speculation of linage 1 and lineage 8 PRRSVs. (A to D) BEAST analysis of NADC30-like PRRSVs. (E to H) BEAST analysis of NADC34-like PRRSVs. (I to L) BEAST analysis of lineage 8. (A, E, and I) Root-to-tip correlations of time sequences of ORF5. (B, F, and J) The time-resolved trees of each lineage. Red branches represent Chinese strains and blue branches show strains from the United States. (C, G, and K) Bayesian skyline population dynamic analysis. The red arrows indicate the point at which the size and genetic diversity of the population changed significantly. (D, H, and L) BEAST calculations of nucleotide substitution rates.

Phylogenetic analysis estimated that NADC30-like PRRSVs formed after 1980; the common ancestor of this lineage was speculated to have originated from strains in the United States (Fig. 7B). BEAST estimation of this cluster obtained by the strict molecular clock model yielded an average substitution rate for ORF5 of 7.966 × 10−3 (Fig. 7D), with a 95% credible interval of 6.943 × 10−3 to 9.031 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year. There was a major import event from the United States to China around 1998 (Fig. 7B), and while an America-China transmission event might have occurred, these strains did not survive long (Fig. 7B). Our Bayesian skyline population (BSP) estimation suggested that the NADC30-like cluster experienced a period of continuous increase in effective population size and relative genetic diversity until approximately 2010, which was followed by a plateau from 2010 to 2015. After 2015, a decline in population size and genetic diversity occurred (Fig. 7C). The estimation suggested that there might be an outbreak of the NADC30-like cluster in the near future.

NADC34-like PRRSVs formed in the early 1990s based on the Bayesian inference, and most were from the United States (Fig. 7F). However, there were two Chinese strains that fell into this cluster in 2017 (LNWK130) and 2018 (CH-2018-NCV-Anheal-1). This indicates there could be some unknown transmission pathway of this cluster from the United States to China. The average substitution rate of this cluster was estimated as 4.275 × 10−3 (Fig. 7H), with a 95% credible interval of 3.470 × 10−3 to 5.111 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year. BSP estimation suggested that population size and genetic polymorphisms of NADC34-like PRRSVs were in a relatively stable state for these years (2003 to 2018) (Fig. 7G).

The L8 lineage formed after 1980 (Fig. 7J), and the average substitution rate was 4.689 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year (Fig. 7L); its 95% credible interval range was 3.942 × 10−3 to 5.457 × 10−3. This lineage was only imported from the United States to China once in approximately 1987 (Fig. 7J). BSP estimation of this lineage suggested that its population underwent a progression from a stable period to a surge in size and diversity, with a subsequent reduction to a trough, followed by a slow recovery (Fig. 7K); the trough in size and diversity may be related to the outbreak of highly pathogenic Chinese PRRSVs in 2006.

DISCUSSION

This study was the first to monitor the PRRSV genetic diversity in China and the United States from 2014 to 2018; we systematically compared the differences in lineage distribution, recombination, NSP2 polymorphisms, and evolutionary dynamics between the two countries. The GenBank full-length genome sequences from 2014 to 2018 included 133 Chinese NA-type PRRSVs comprising L1, L3, and L8 and 84 NA-type PRRSVs from the United States comprising L1, L5, and L8. Sequenced samples from this study accounted for 63% of the GenBank database, including 36 Chinese strains and 102 US strains. This narrowed the gap between Chinese and US PRRSVs in the GenBank database and covered the China-predominant lineages L1, L3, and L8 and the US-predominant lineages L1, L5, L7, and L8. The overall range of data analyzed from 2014 to 2018 was approximately similar to the scale of pig raising in China and the United States, which provided a suitable model to detect the genetic variation lineage distribution of PRRSV.

Recombination is a pervasive phenomenon among PRRSV isolates and is an important strategy for the generation of viral genetic diversity (18). NA-type PRRSVs in China and the United States were systematically analyzed for inter- and intralineage recombination and compared between China and the United States. During the analysis of recombination, we checked recombination breakpoints in the PRRSVs sequenced in this study. Results showed that these were not adjacent to the corresponding primer-binding sites, which suggested that all recombinant strains comprised field recombination events rather than laboratory artifacts. In our previous study, we compared the methods of NGS and Sanger sequencing in PRRSV genome sequencing and found that the results of the two sequencing methods were highly consistent (99.3% to 99.9%) (19). To further verify the consistency between NGS and Sanger methods, we randomly selected 4 recombination breakpoints of PRRSV, and PCR was performed to amplify both sides of the recombinant breakpoints (approximately 1,000 bp). Each PCR fragment was cloned into the pMD18-T vector, and DNA was sequenced with three single colonies by Sanger sequencing. The results showed that the Sanger sequencing results were highly consistent with those of NGS (99.0% to 99.5%). To avoid the identification of false recombination hot spots caused by the continuous passage of strains, we removed passaged strains from GenBank when selecting the recombination analysis database. In addition, we screened the recombinants that were suspected to have originated from a single recombination event.

Interestingly, between the years 2014 and 2018, the high-frequency interlineage recombination regions in China and the United States were both located in NSP9 and GP2 to GP3. NSP9 is involved in the replication of PRRSV (as a member of the arterivirus family) (20) while GP2 and GP4 are the major determinants of arterivirus entry into cultured cells (21). The recombination of PRRSV at these regions might be associated with an increase in replication capacity and cellular tropism, which presumably makes it easier to survive and spread, and ultimately drives the pathogenesis of PRRSV. Identification of shared recombinant regions in independent recombination events indicated that sequence compositions (RNA secondary structure, subgenomic RNA, and nucleic acid homology) may exist near the region that promotes recombination (22–24). Further exploration of that potential mechanism is required. However, the obvious difference in recombination hot spots of Chinese PRRSV recombinants between 1991–2013 and 2014–2018 was probably due to the importation of L1 PRRSV from North America during that time frame (25). Moreover, recombination hot spots were generally not shared between the various data sets (between the 1991–2013 and 2014–2018 data sets or between intralineage and interlineage data sets). We were unsure whether changes in certain properties of the virus or whether random samples produced these different hot spots. Since there was no background control, it was very difficult to confirm the causation of this observation. We guessed that differences in epidemic virus and population density led to changeable viral properties; however, this requires further study.

In addition, we found several commonalities and differences in recombination patterns between China and the United States. Our data reflected that the major parents of recombinants in China and the United States have gradually concentrated on lineage 1 PRRSVs in recent years, which might be due to the lack of vaccine protection and poor fidelity in the lineage, which is more susceptible to mutation. Furthermore, lineage 1 PRRSVs were extremely active in the recombination event, which we speculated may be due to some PRRSV genotypes that were more susceptible to recombination. For example, in China, during 1991–2013, the numbers of lineage 5 PRRSVs and lineage 8 PRRSVs as major epidemical strains were relatively high; however, a few recombination events between the two lineages were detected during coinfection. On the contrary, the epidemic strains from 2014 to 2018, lineage 1 and lineage 8 PRRSVs, were involved in more recombination events during coinfection. For PRRSVs detected in the United States from 1992 to 2013, there were a few recombination events in lineage 5 PRRSVs, which were prevalent strains. In the years 2014 to 2018, more recombination events were detected in prevalent lineage 1 PRRSVs. Furthermore, regarding the relationship between coinfection rate and recombination rate, there was not enough data to support a relationship. We intend to expand the analyses at the experimental level in the next study to assess whether certain genotypes were more or less likely to recombine. From 1991–2013 to 2014–2018, the recombination patterns of recombinants in China and the United States gradually simplified. Specifically, the Chinese recombination patterns were mainly L1+L8 and L8+L1, whereas recombination patterns in the United States focused on L1+L5. Moreover, the recombination frequency in L1 PRRSVs and the overall recombination frequency of recombinants in China were higher than those of recombinants in the United States. These frequency differences could be due to alterations in prevalent strains and attenuated vaccines in China and the United States. Overall, whether in China or the United States, from 1991–2013 to 2014–2018, the concentration of recombination hot spots and recombinant parents demonstrated that dominant strains might utilize recombination strategies to achieve population growth.

Intralineage recombination of PRRSVs in China and the United States varied greatly. Of the three lineages prevalent in China during 2014–2018, L1, L3, and L8 exhibited widespread recombination, but the recombination hot spots were more concentrated (Fig. 5C). Among the four prevalent lineages in the United States, only L1 comprised a large number of recombinant strains, whereas in the L5, L7, and L8 strains, no recombination was determined. Recombination hot spots in the United States were scattered throughout the genome (Fig. 5E and F), and most recombinant fragments were smaller than those in China (Fig. 5A and D). The widespread intralineage recombination in these three Chinese lineages might be related to the current use of multiple vaccines. The intralineage recombination frequency is generally considered to be higher than that of interlineage recombination, but our results suggest the opposite. This might be due to the use of set representative strains as reference parents for interlineage recombination testing, while specific parents are screened for intralineage recombination testing.

In addition to recombination, NSP2 polymorphism is another significant factor that contributes to the high variation of the PRRSV genome. Previous studies have not systematically classified diverse NSP2 patterns. Based on GenBank’s published data from 1991 to 2018 and the sequences provided in this study, the NSP2s of PRRSVs were divided into five groups (Fig. 6). Three groups were characterized by “111 + 1 + 19,” “100” deletions, and a 36-aa insertion, with a large number of strains sorted out, in addition to the no insertion or deletion group represented by VR-2332 and the “1 + 29” deletion group represented by highly pathogenic PRRSV (Fig. 6A). There was not high regularity between the classification criterion of ORF5 lineages and NSP2 polymorphisms (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, while the “111 + 1 + 19” deletion previously represented an L1 deletion feature, it also existed in some of the L3 or L8 strains. Similarly, strains with the “100” deletion feature were regarded as NADC34-like PRRSVs, and there were NADC30-like PRRSVs that also demonstrated this feature. The inconsistency between NSP2 patterns and ORF5 lineages might have resulted from the recombination of PRRSVs. Another deletion in PNSP24.3, a further deletion at 628 to 747 which followed the “1 + 29” signature, was related to the vaccine strain TJM-F92 (26). Further functional studies of different NSP2 indel patterns might contribute to a deeper understanding of PRRSV viruses, virus-host interactions, and virus evolution and could even provide new targets to determine the genetic diversity of PRRSV in addition to the ORF5-based lineage system.

From the perspective of molecular evolutionary dynamics, NADC30-like PRRSVs are currently undergoing a reduction in genetic diversity (Fig. 7C), which is in line with the trend in which the diversity of a certain genotype is reduced as it becomes the dominant population, before the occurrence of an epidemic. Moreover, although NADC34-like PRRSVs isolated in the United States were stable and only occasionally detected in China (Fig. 7G), our data indicate the need to guard against related viruses. Viruses of this cluster should be monitored, especially with respect to import controls.

These results will help us to understand the recombination of PRRSV and strengthen viral inspection before mixing herds of swine to reduce the probability of novel recombinant variants; it will also provide new clues for next-generation vaccines that are recombination insensitive. Combining PRRSV recombination, NSP2 polymorphisms, and molecular evolutionary dynamics in China and the United States, including joint monitoring and control between the two countries, would help with future prevention and control of PRRSV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

One-hundred thirty-eight PRRSV PCR-positive samples collected from 2014 to 2018 from pigs with high fever, reproductive, or respiratory syndromes were used in this study. Of the 138 samples, 36 samples were collected from different farms in 13 provinces of China. The other 102 PRRSVs were collected from the United States; 50 of the 102 samples were from 13 states of the United States, whereas the remaining 52 samples lacked state information.

Sample processing and Sanger sequencing.

The 36 sample tissues collected from China were homogenized, and viral RNA was extracted using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The whole-genome sequences were amplified with nine pairs of primers, resulting in nine overlapping fragments (see Table S7 in the supplemental material). The amplified PCR products were gel purified using a Gel Extraction kit (Omega, USA), cloned into the pMD18-T vector (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), and then sequenced by the Sanger method for at least five independent clones (Comate Bioscience, Jilin, China). The full-length sequences were assembled using the SeqMan program in DNAStar 7.0 software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA).

Next-generation sequencing and genome assembly.

To obtain whole genomic sequences, the 102 samples from the United States were subjected to next-generation sequencing (NGS) on a MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) as previously described (27). Specifically, the DNA from the extracted sample DNA/RNA was cleared with the RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and residual reagent was then removed from the remaining RNA with the Agencourt RNAClean XP kit (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manual. The library was prepared using the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to kit instructions. The normalized library was sequenced on a MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA) with 300-cycle MiSeq Reagent Micro kit V2 (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

Raw sequencing data were subjected to data cleaning by removing adapters, trimming low-quality ends, and depleting sequences with lengths of <36 nucleotides and to sequencing quality analysis with FastQC (28). The taxonomy of cleaned reads was classified using Kraken v0.10.5-beta (29). Reads of particular/interesting viruses were extracted from the Kraken classification results as candidate reads of that taxon. Particularly, PRRSV fragments were extracted and de novo assembled with SPAdes (v 3.5.0) based on candidate reads (30).

Data set.

In addition to the 138 complete genome sequences (sampled during 2014–2018) obtained in this study, we included another 217 public ORF5 sequences for phylogenetic analyses, which covered the time period from 2014 to 2018 and were derived from the full-length PRRSV genomes downloaded from GenBank (see Table S1). In addition to this data set, 358 full-genome GenBank sequences from 1991 to 2013 were included in the recombination analyses. To study NSP2 polymorphisms, 713 NSP2 amino acid sequences were derived from full-genome sequences, which represented the diversity of viruses in China and the United States from 1991 to 2018. For spatiotemporal analyses in BEAST, the ORF5 sequences representative of the diversity and temporal structure of PRRSV in China and the United States, as well as in each cluster, were selected and then processed through ORF5 recombination detection using RDP v.4.96 (31). ORF5 sequences suspected to be recombinants were removed. Three data sets, which included a NADC30-like group (n = 423), a NADC34-like group (n = 96), and an L8-related group (n = 395), were obtained and analyzed by BEAST.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The alignment of 355 ORF5 sequences was subjected to recombination screening using RDP v.4.96. Nine potential recombinants in ORF5 regions were identified and then removed, and an alignment of 346 sequences was generated for subsequent phylogenetic analysis. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using RAxML-NG (32) with 1,000 bootstrap replicates, and GTRGAMMA was used as the nucleotide substitution model. The lineages were classified according to the genetic relationship among all 346 ORF5 sequences and 38 reference sequences. According to the classification criteria of PRRSV lineages by Shi et al. (11), five lineages corresponding to lineage 1, 3, 5, 7, and 8 were finally determined, with intralineage diversity levels of <11% (with an exception of lineage 1, which might be due to evolution). ClusterPicker software was used to further divide the lineage into sublineages according to previous studies (33, 34) (Fig. S1).

Recombination analysis.

For interlineage recombination analysis, the recombination events were characterized in SimPlot software v3.5 (35). Nine representative strains were selected from L1 to L9 as reference parents as follows: NADC30 (L1), XW008 (L2), MD001 (L3), EDRD-1 (L4), VR-2332 (L5), P129 (L6), SP (L7), JXA1 (L8), and MN30100 (L9). No recombination events occurred in the reference strains based on software prediction and time inference. The recombination parental strains and breakpoint locations were determined based on a full-genome similarity plot analysis implemented in SimPlot, with a window size of 500 bp and step size of 20 bp. Interlineage recombination analysis was also performed using RDP v.4.96 according to a previous study (36), and recombination events were indicated when three of seven methods reported recombination signals. These methods included RDP (37), BOOTSCAN (38), MAXCHI (39), CHIMAERA (40), 3SEQ (41), GENECONV (42), and SISCAN (43). Default parameters were used, except for the number of bootstrap replicates, which was replaced by 500 and the cutoff percentage was set to 95 in BOOTSCAN. Recombination events with only sufficient evidence (not partial or trace evidence in the same event) and both parental strains unambiguously identified (i.e., no missing parental strain scenario) were kept. The final recombination events were determined after taking into consideration both the RDP and SimPlot results.

Intralineage recombination analysis was performed based on the full-genome collection of each lineage. For every lineage in each country, recombination detection was performed independently using RDP v.4.96, with the same parameter settings and screening methods as described in the previous section. Recombination events and breakpoint distributions were shown using Circos (44) and ggplot2.

The recombination frequency for each site was the percentage of recombinations that occurred at a specific site from the total number of recombinants. The frequencies of interlineage and intralineage recombination were the percentages of recombinants out of all of the strains in each statistical unit (between 1991–2013 and 2014–2018, between China and the United States, and between the strains downloaded from GenBank and the strains sequenced).

Shared-origin recombinants were collapsed to rule out that hot spots were caused by progenies inherited by ancestor recombinant strains. Collapsing methodology of suspicious recombination progenies was as follows: first, the recombination frequency at each location was calculated, based on the assumption that the recombinant was from an independent recombination event. A recombination hot spot was defined by a position with a recombination percentage higher than 25%. Second, to exclude recombinants that shared the same recombination regions from the common ancestor, comparisons were performed based on phylogenetic structure, homology, and the positions of breakpoints. The 7,700 to 8,300 nt and 12,200 to 13,700 nt (extended 400 bp) sequences of the Chinese recombinants and 12,300 to 13,400 nt (extended 400 bp) sequences of recombinants in the United States were selected for neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree analyses. When the recombination regions clustered in same branch, homologous comparisons were performed between them. These recombinants were thought to come from a common ancestor when homologies of all of their shared recombination regions were more than 99% and there were no additional recombination regions. Third, for the recombinants that were suspected of being from a common ancestor, only the one with the earliest appearance was retained, and the recombination frequency at each location was recalculated. Due to the presence of an increased number of intralineage recombination hot spots, the homology test standard was reduced to 95% (the data before removing potential recombination progenies are shown in Tables S4 and S5).

Classification of NSP2 polymorphic patterns.

To determine the various insertion and deletion (indel) patterns of NSP2, an optimized sequence alignment was obtained according to the following procedures. First, 713 complete genome sequences of all NA-type PRRSVs from 1991 to 2018 were aligned with VR-2332 as a reference using Clustal Omega (45). Second, the alignment was split to get NSP2 sequences based on the VR-2332 annotation. Third, NSP2 was realigned based on amino acid sequences by Clustal Omega and then converted to nucleotide alignment in PAL2NAL software (46), followed by manual modifications to correct a few obvious errors. After obtaining an accurate alignment, five large patterns were clearly distinguished based on the filled gaps. Indels that were shared in each large pattern were thought to be the characteristic background of the large pattern, Smaller patterns were further divided based on indel information of all of the strains in each large pattern; 25 subdivided patterns were obtained. Furthermore, the total number of strains in each pattern sampled in the available data set up to the time point of each strain that appeared was calculated. A cumulative quantity curve was generated, with each time point as the x coordinate and the sum of all strains until this time point as the y coordinate, which reflected the changes of population size and duration in each pattern.

BEAST analysis.

The time-scaled trees of L1 and L8 were estimated using the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo method, implemented in BEAST2 (47) (Fig. 7A, E, and I), with a strict clock model and GTRGAMMA substitution model. For this, 80 million, 50 million, and 80 million steps were run for Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo analyses of NADC30-like PRRSVs, NADC34-like PRRSVs, and L8-related strains, respectively, 10% of which was removed as burn-in. The trees and other parameters were sampled every 10,000 steps.

Data availability.

The nucleotide sequences of PRRSVs sequenced in the present study have been deposited in GenBank (accession no. MN046221 to MN046243, MN073081 to MN073182, and MH651736 to MH651748).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by grants from the Foundation for Science and Technology Innovative Talents of Harbin (2016RAQXJ142), the Heilongjiang Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (JC2017010), the State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Biotechnology Research Fund (SKLVBF201902), the China Ministry of Science and Technology Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC1200805), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91631110).

We thank the core facility and technical support at Wuhan Institute of Virology for assistance with the technology and platform.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collins JE, Benfield DA, Christianson WT, Harris L, Hennings JC, Shaw DP, Goyal SM, McCullough S, Morrison RB, Joo HS. 1992. Isolation of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332) in North America and experimental reproduction of the disease in gnotobiotic pigs. J Vet Diagn Invest 4:117–126. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumann EJ, Kliebenstein JB, Johnson CD, Mabry JW, Bush EJ, Seitzinger AH, Green AL, Zimmerman JJ. 2005. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome on swine production in the United States. J Am Vet Med Assoc 227:385–392. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.227.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian K, Yu X, Zhao T, Feng Y, Cao Z, Wang C, Hu Y, Chen X, Hu D, Tian X, Liu D, Zhang S, Deng X, Ding Y, Yang L, Zhang Y, Xiao H, Qiao M, Wang B, Hou L, Wang X, Yang X, Kang L, Sun M, Jin P, Wang S, Kitamura Y, Yan J, Gao GF. 2007. Emergence of fatal PRRSV variants: unparalleled outbreaks of atypical PRRS in China and molecular dissection of the unique hallmark. PLoS One 2:e526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson CR, Griggs TF, Gnanandarajah J, Murtaugh MP. 2011. Novel structural protein in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus encoded by an alternative ORF5 present in all arteriviruses. J Gen Virol 92:1107–1116. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.030213-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snijder EJ, van Tol H, Roos N, Pedersen KW. 2001. Non-structural proteins 2 and 3 interact to modify host cell membranes during the formation of the arterivirus replication complex. J Gen Virol 82:985–994. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-5-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wootton S, Yoo D, Rogan D. 2000. Full-length sequence of a Canadian porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) isolate. Arch Virol 145:2297–2323. doi: 10.1007/s007050070022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelsen CJ, Murtaugh MP, Faaberg KS. 1999. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus comparison: divergent evolution on two continents. J Virol 73:270–280. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.1.270-280.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forsberg R. 2005. Divergence time of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus subtypes. Mol Biol Evol 22:2131–2134. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanada K, Suzuki Y, Nakane T, Hirose O, Gojobori T. 2005. The origin and evolution of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses. Mol Biol Evol 22:1024–1031. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao JC, Xiong JY, Ye C, Chang XB, Guo JC, Jiang CG, Zhang GH, Tian ZJ, Cai XH, Tong GZ, An TQ. 2017. Genotypic and geographical distribution of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses in mainland China in 1996–2016. Vet Microbiol 208:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi M, Lam TT, Hon CC, Murtaugh MP, Davies PR, Hui RK, Li J, Wong LT, Yip CW, Jiang JW, Leung FC. 2010. Phylogeny-based evolutionary, demographical, and geographical dissection of North American type 2 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses. J Virol 84:8700–8711. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02551-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang Y, Kim DY, Ropp S, Steen P, Christopher-Hennings J, Nelson EA, Rowland RR. 2004. Heterogeneity in Nsp2 of European-like porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses isolated in the United States. Virus Res 100:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong GZ, Zhou YJ, Hao XF, Tian ZJ, An TQ, Qiu HJ. 2007. Highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome, China. Emerg Infect Dis 13:1434–1436. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.070399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brockmeier SL, Loving CL, Vorwald AC, Kehrli ME Jr, Baker RB, Nicholson TL, Lager KM, Miller LC, Faaberg KS. 2012. Genomic sequence and virulence comparison of four type 2 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus strains. Virus Res 169:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Geelen AGM, Anderson TK, Lager KM, Das PB, Otis NJ, Montiel NA, Miller LC, Kulshreshtha V, Buckley AC, Brockmeier SL, Zhang J, Gauger PC, Harmon KM, Faaberg KS. 2018. Porcine reproductive and respiratory disease virus: evolution and recombination yields distinct ORF5 RFLP 1-7-4 viruses with individual pathogenicity. Virology 513:168–179. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu JK, Zhou X, Zhai JQ, Li B, Wei CH, Dai AL, Yang XY, Luo ML. 2017. Emergence of a novel highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in China. Transbound Emerg Dis 64:2059–2074. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou L, Kang R, Yu J, Xie B, Chen C, Li X, Xie J, Ye Y, Xiao L, Zhang J, Yang X, Wang H. 2018. Genetic characterization and pathogenicity of a novel recombined porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus 2 among Nadc30-like, Jxa1-like, and Mlv-like strains. Viruses 10:551. doi: 10.3390/v10100551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen N, Yu X, Wang L, Wu J, Zhou Z, Ni J, Li X, Zhai X, Tian K. 2013. Two natural recombinant highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses with different pathogenicities. Virus Genes 46:473–478. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-0892-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Zheng Y, Xia XQ, Chen Q, Bade SA, Yoon KJ, Harmon KM, Gauger PC, Main RG, Li G. 2017. High-throughput whole genome sequencing of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus from cell culture materials and clinical specimens using next-generation sequencing technology. J Vet Diagn Invest 29:41–50. doi: 10.1177/1040638716673404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao K, Gao J-C, Xiong J-Y, Guo J-C, Yang Y-B, Jiang C-G, Tang Y-D, Tian Z-J, Cai X-H, Tong G-Z, An T-Q. 2018. Two residues in NSP9 contribute to the enhanced replication and pathogenicity of highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Virol 92:e02209-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02209-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian D, Wei Z, Zevenhoven-Dobbe JC, Liu R, Tong G, Snijder EJ, Yuan S. 2012. Arterivirus minor envelope proteins are a major determinant of viral tropism in cell culture. J Virol 86:3701–3712. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06836-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, Cockrell SK, Kolawole AO, Rotem A, Serohijos AW, Chang CB, Tao Y, Mehoke TS, Han Y, Lin JS, Giacobbi NS, Feldman AB, Shakhnovich E, Weitz DA, Wobus CE, Pipas JM. 2015. Isolation and analysis of rare norovirus recombinants from coinfected mice using drop-based microfluidics. J Virol 89:7722–7734. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01137-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bull RA, Hansman GS, Clancy LE, Tanaka MM, Rawlinson WD, White PA. 2005. Norovirus recombination in ORF1/ORF2 overlap. Emerg Infect Dis 11:1079–1085. doi: 10.3201/eid1107.041273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan S, Nelsen CJ, Murtaugh MP, Schmitt BJ, Faaberg KS. 1999. Recombination between North American strains of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res 61:87–98. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(99)00029-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao K, Ye C, Chang XB, Jiang CG, Wang SJ, Cai XH, Tong GZ, Tian ZJ, Shi M, An TQ. 2015. Importation and recombination are responsible for the latest emergence of highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in China. J Virol 89:10712–10716. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01446-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leng X, Li Z, Xia M, He Y, Wu H. 2012. Evaluation of the efficacy of an attenuated live vaccine against highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in young pigs. Clin Vaccine Immunol 19:1199–1206. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05646-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Q, Wang L, Yang C, Zheng Y, Gauger PC, Anderson T, Harmon KM, Zhang J, Yoon KJ, Main RG, Li G. 2018. The emergence of novel sparrow deltacoronaviruses in the United States more closely related to porcine deltacoronaviruses than sparrow deltacoronavirus HKU17. Emerg Microbes Infect 7:105. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0108-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood DE, Salzberg SL. 2014. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol 15:R46. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. 2011. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, Khoosal A, Muhire B. 2015. RDP4: detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol 1:vev003. doi: 10.1093/ve/vev003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kozlov AM, Darriba D, Flouri T, Morel B, Stamatakis A. 2019. RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable, and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 35:4453–4455. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ragonnet-Cronin M, Hodcroft E, Hue S, Fearnhill E, Delpech V, Brown AJ, Lycett S, UK HIV Drug Resistance Database. 2013. Automated analysis of phylogenetic clusters. BMC Bioinformatics 14:317. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paploski IAD, Corzo C, Rovira A, Murtaugh MP, Sanhueza JM, Vilalta C, Schroeder DC, VanderWaal K. 2019. Temporal dynamics of co-circulating lineages of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Front Microbiol 10:2486. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lole KS, Bollinger RC, Paranjape RS, Gadkari D, Kulkarni SS, Novak NG, Ingersoll R, Sheppard HW, Ray SC. 1999. Full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes from subtype C-infected seroconverters in India, with evidence of intersubtype recombination. J Virol 73:152–160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.1.152-160.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi M, Holmes EC, Brar MS, Leung FC. 2013. Recombination is associated with an outbreak of novel highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses in China. J Virol 87:10904–10907. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01270-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin D, Rybicki E. 2000. RDP: detection of recombination amongst aligned sequences. Bioinformatics 16:562–563. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salminen MO, Carr JK, Burke DS, McCutchan FE. 1995. Identification of breakpoints in intergenotypic recombinants of HIV type 1 by bootscanning. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 11:1423–1425. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith JM. 1992. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J Mol Evol 34:126–129. doi: 10.1007/bf00182389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Posada D, Crandall KA. 2001. Evaluation of methods for detecting recombination from DNA sequences: computer simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:13757–13762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241370698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boni MF, Posada D, Feldman MW. 2007. An exact nonparametric method for inferring mosaic structure in sequence triplets. Genetics 176:1035–1047. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.068874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Padidam M, Sawyer S, Fauquet CM. 1999. Possible emergence of new geminiviruses by frequent recombination. Virology 265:218–225. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibbs MJ, Armstrong JS, Gibbs AJ. 2000. Sister-scanning: a Monte Carlo procedure for assessing signals in recombinant sequences. Bioinformatics 16:573–582. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.7.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. 2009. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res 19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suyama M, Torrents D, Bork P. 2006. PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res 34:W609–W612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bouckaert R, Heled J, Kuhnert D, Vaughan T, Wu CH, Xie D, Suchard MA, Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. 2014. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput Biol 10:e1003537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The nucleotide sequences of PRRSVs sequenced in the present study have been deposited in GenBank (accession no. MN046221 to MN046243, MN073081 to MN073182, and MH651736 to MH651748).