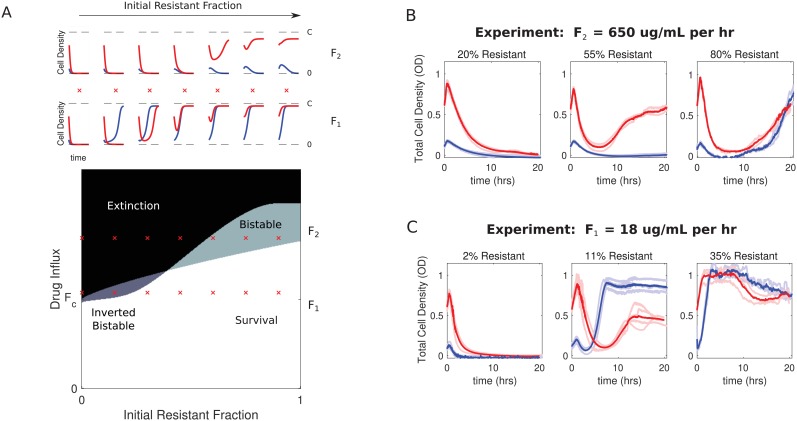

Figure 3. Bistability may favor survival of populations with highest or lowest initial density.

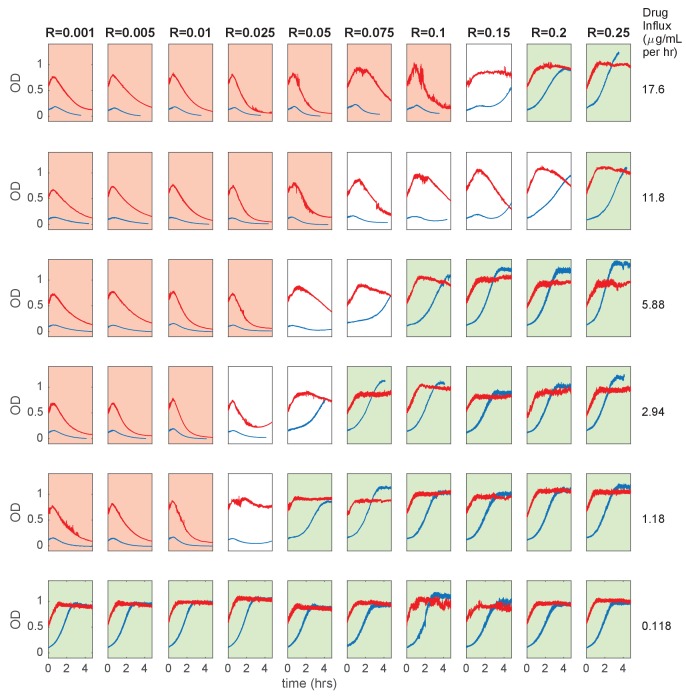

(A) Main panel: phase diagram indicating regions of extinction (black), survival (white), bistability (light gray; initially large population survives, small population dies), and ‘inverted’ bistability (dark gray; initially small population survives, large population dies). Red ’x’ marks correspond to the subplots in the top panels. Top panels: time-dependent population sizes starting from a small population (OD = 0.1, blue) and large population (OD = 0.6, red) at constant drug influx of (large drug influx) and (small drug influx). is the critical influx rate above which the extinct solution (population size 0) first becomes stable; it depends on model parameters, including media refresh rate (µ), maximum kill rate of the antibiotic (), the Hill coefficient of the dose response curve (), and the MIC of the drug-resistant population in the low-density limit where cooperation is negligible (). Specific numerical plots were calculated with , , , , , , , , and . (B) Experimental time series for mixed populations starting at a total density of OD = 0.1 (blue) or OD = 0.6 (red). The initial populations are comprised of resistant cells at a total population fraction of 0.2 (left), 0.55 (center), and 0.80 right) for influx rate µg/mL. Light curves are individual experiments, dark curves are means across all experiments. (C) Experimental time series for mixed populations starting at a total density of OD = 0.1 (blue) or OD = 0.6 (red). The initial populations are comprised of resistant cells at a total population fraction of 0.02 (left), 0.11 (center), and 0.35 right) for influx rate µg/mL. Light curves are individual experiments, dark curves are means across all experiments.

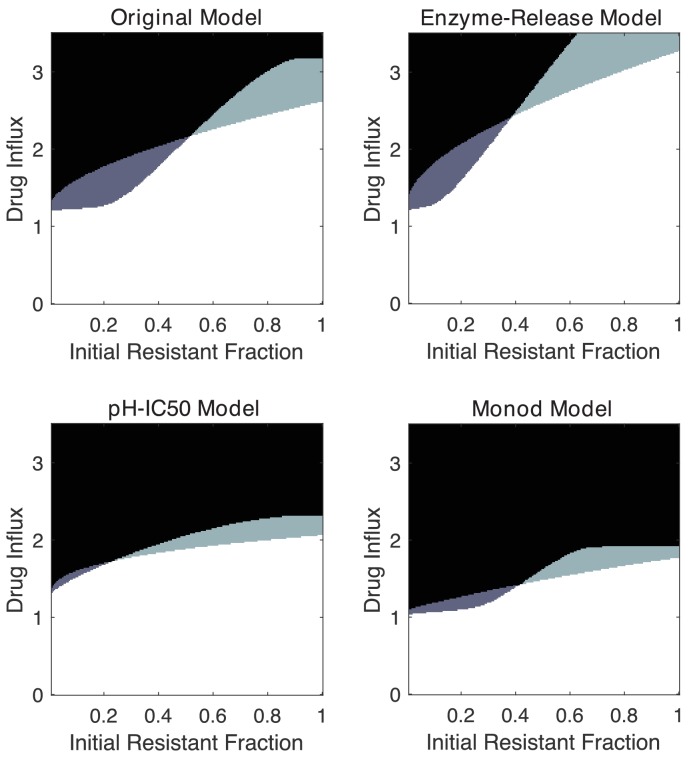

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Alternative mathematical models exhibit similar qualitative features, including inverted bistability.

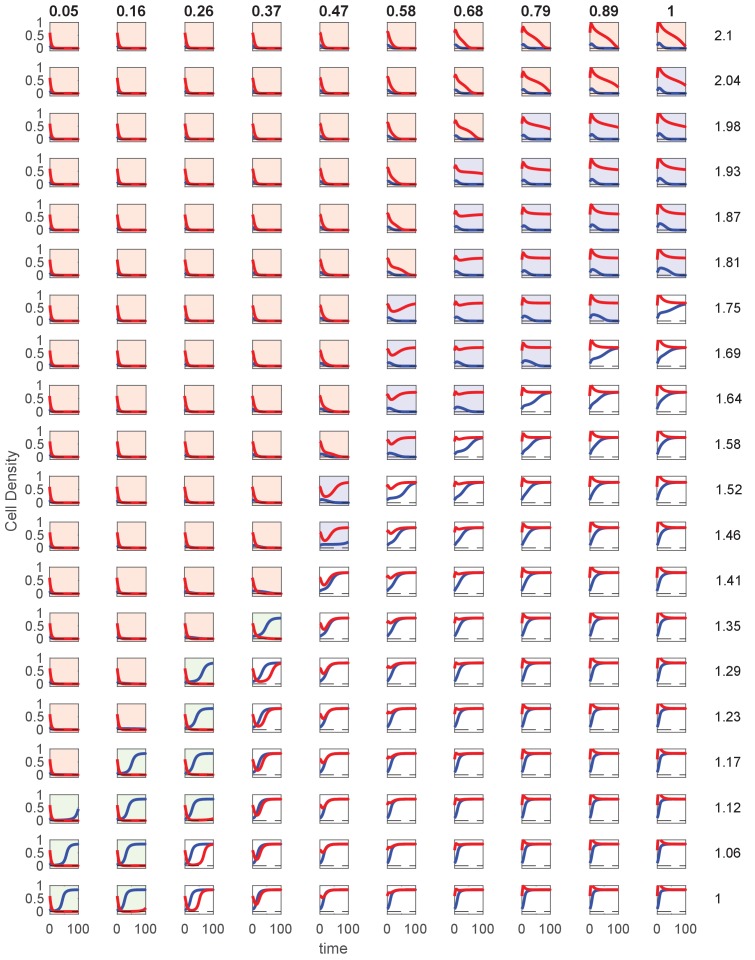

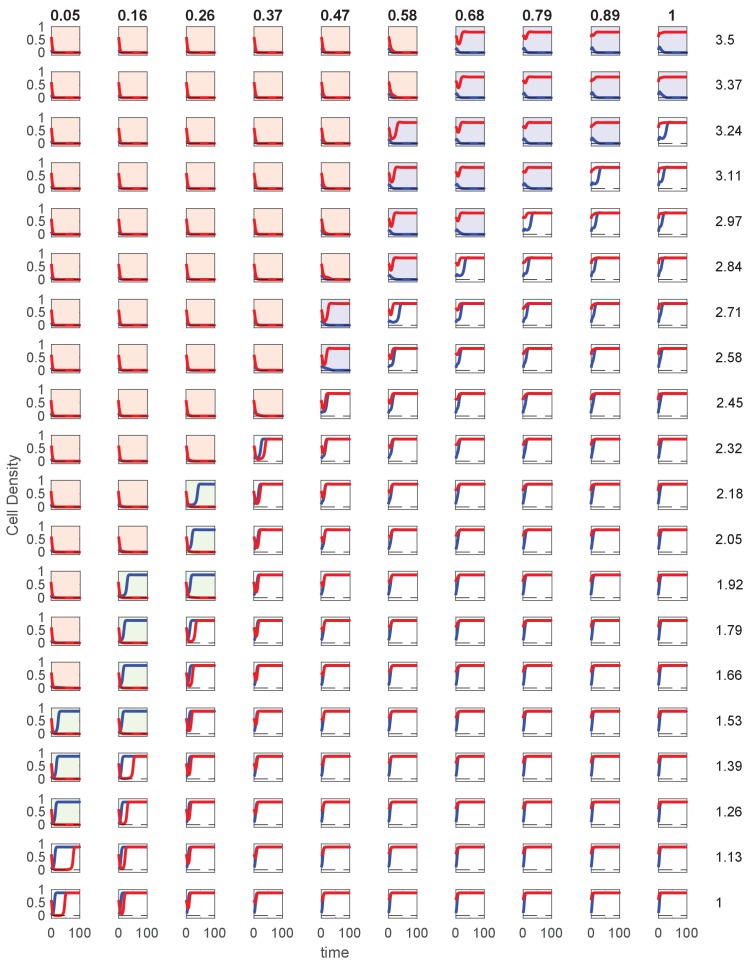

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. Time series of cell density for simulations starting from high- or low-density populations in Monod growth model.

Figure 3—figure supplement 3. Short experiments to explore parameter space for inverted bistability.

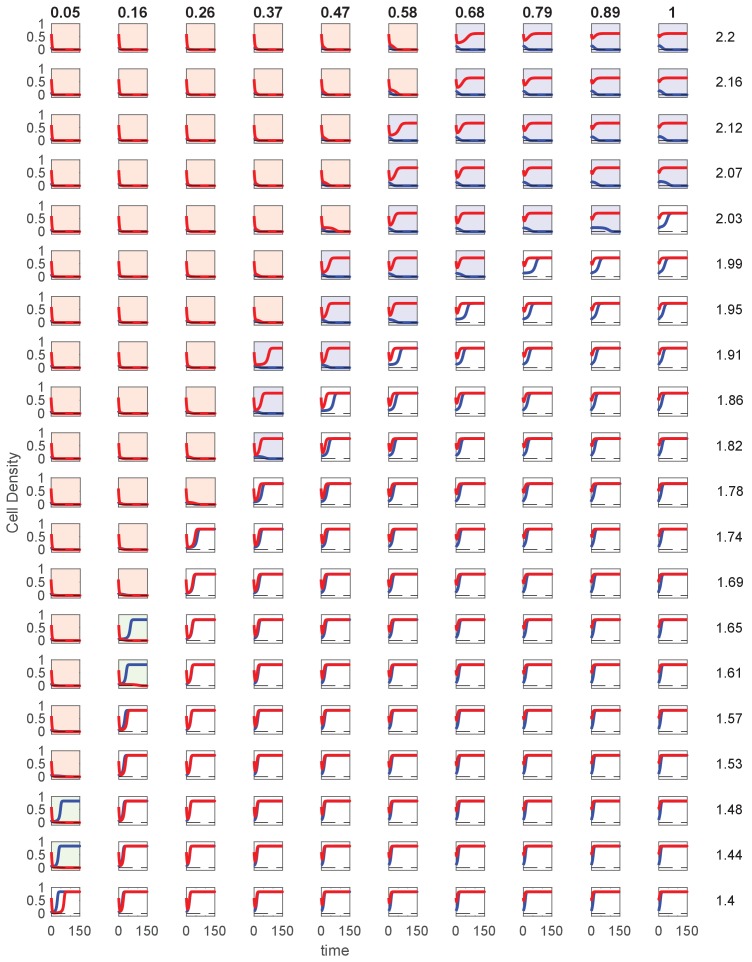

Figure 3—figure supplement 4. Time series of cell density for simulations starting from high- or low-density populations in enzyme release model.

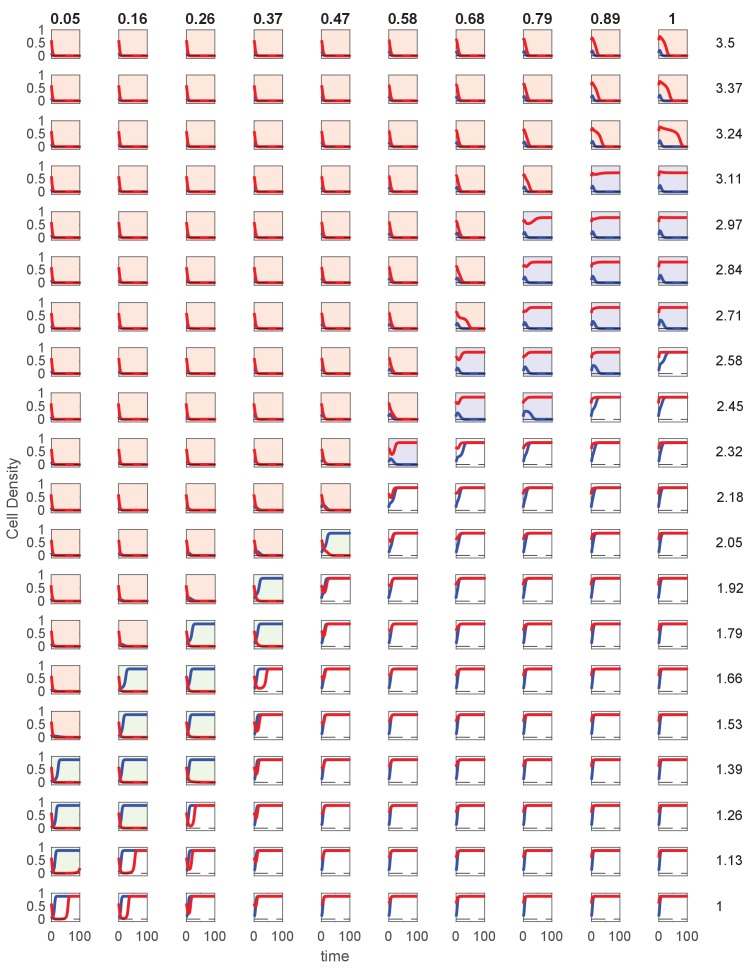

Figure 3—figure supplement 5. Time series of cell density for simulations starting from high- or low-density populations in pH-IC50 model.

Figure 3—figure supplement 6. Time series of cell density for simulations starting from high or low-density populations.

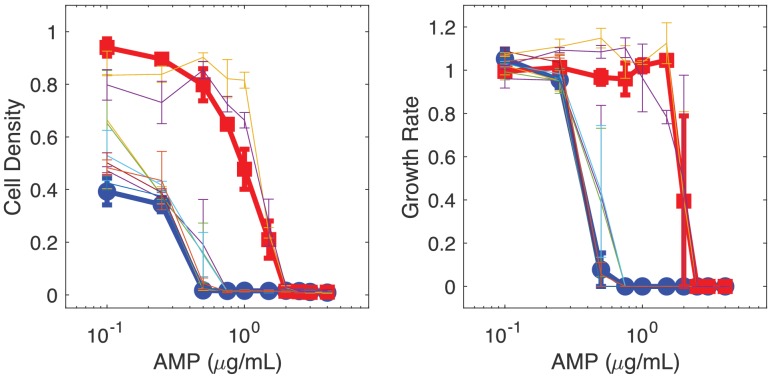

Figure 3—figure supplement 7. Isolates from populations exhibiting collapse but not complete extinction show similar dose-response behavior as original strains.

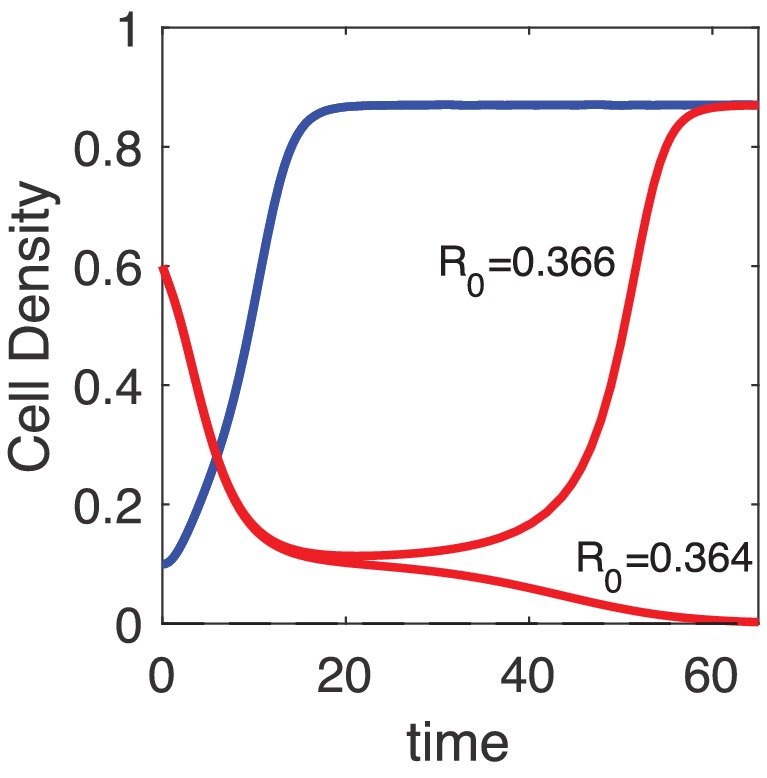

Figure 3—figure supplement 8. Populations exhibit transient periods of approximately constant density near regions of inverted bistability.