Introduction:

Female physicians are becoming neurologists at an increasing rate. In fact, 44.7% of active neurology residents and fellows in accredited programs were female in 2017 compared to only 29.4% of practicing neurologists.1, 2 Despite this trend, sex disparities are evident with increasing academic rank. For full-time faculty in neurology at all United States (U.S.) medical schools, the proportion of female assistant professors, associate professors, and full professors were 47%, 38%, and 21%, respectively. This trend closely mirrors averaged numbers of all specialties when combined.3 This disparity has been dubbed the “leaky pipeline” with decreasing percentages of females with increasing rank in academia.4, 5 There is also a lower proportion of women in certain subspecialty fields. In 2017, only 31.3% of vascular neurology fellows were female.1

In contrast, nursing and allied health professions remain female-dominated fields.6, 7 In 2015, only 6% of nursing school faculty were male, and only 8% of registered nurses were male.6, 8 In 2013, physical therapy program directors were 41% male, while physical therapy students were only 34% male, suggesting an overrepresentation of males in physical therapy leadership.9

Research accomplishments and national and international peer esteem support promotion in academia, therefore opportunities to present at scientific conferences are important for career advancement. Several studies have published trends of sex differences among speakers at major scientific events and medical conferences across specialties. Even when accounting for sex differences among attendees, many conferences report that speaker line-ups are significantly male-dominated.10–21 Acknowledging trends in demographic data of major scientific events is an important step to increasing female representation in the future.22 In just two years after publishing sex imbalance in its invited speakers, the American Society of Microbiology was able to achieve a nearly complete balance of featured presenters at its general meeting in 2015.10

Few studies have analyzed demographic variables of non-physician speakers, such as physician assistants, registered nurses and allied health professionals, at major scientific meetings. No published English language studies to date have analyzed these trends in speakers at major conferences in the field of neurology. Using data published by the American Heart Association, we sought to determine trends in the demographics of speakers by sex among those invited to speak at the International Stroke Conference (ISC) over a five-year period (2014–2018). We hypothesize that significant sex differences exist for invited speakers at the ISC.

Methods:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. In this retrospective study, ISC invited speaker data from 2014 to 2018 were obtained from the American Heart Association. Speaker data included only those who accepted the invitation from the program committee. Information on those invited speakers who declined was not available. Oral abstracts and moderated poster sessions that were selected after peer review were not included in this study. Data on those who presented multiple abstracts that were selected as oral abstracts based on submission were not included. Invited speaker characteristics were obtained from electronic ISC registration information. Beginning in 2014, sex data have been included in registration; therefore we began data gathering with the year 2014. These data are public record that is volunteered at registration.

At registration, the participant chose between the options male, female, or do not wish to disclose as their sex designation. If sex was not disclosed at registration, it was considered missing data. Overall, 1.1% of invited speakers did not disclose sex information. As the terms male and female represent sex, we use the term sex instead of gender in this manuscript.

Variables abstracted from the database included invited speaker sex, degree, race, session type, institution country, and presentation category (Supplemental Material Table I). Some variables were grouped for analysis, including speaker degree, institution country, and presentation category. Speakers with a medical degree (MD), which included Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) and other physician degrees according to the conferring institution, and both MD and Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) were combined in the physician group. Speakers with a PhD or other doctorate in research were combined in the research scientist group. The midlevel group included nurse practitioners and physician assistants with and without doctoral degrees. The nurse group included all registered nurses, including those with Master’s degrees. Allied health professionals included physical therapists, occupational therapists, and pharmacists. Other degrees included Master’s and Bachelor’s degrees in science, arts, and public health. Doctors of Jurisprudence were also included in the other degrees group.

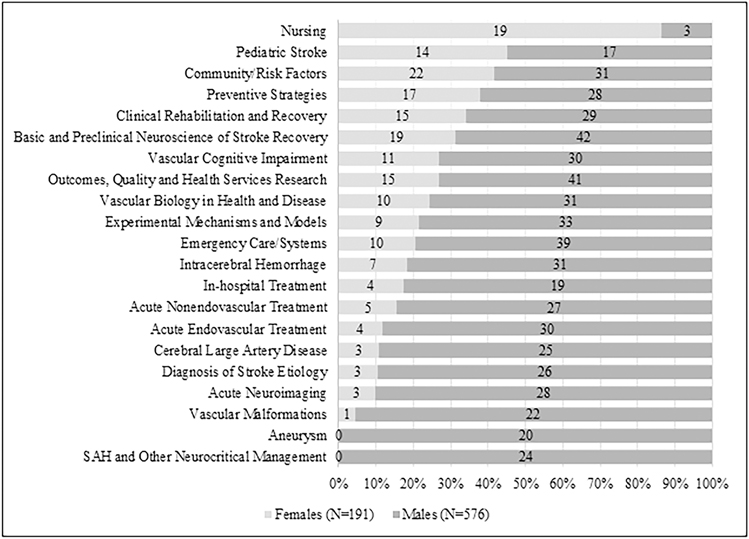

Speaker institution countries were classified by continent for analysis. ISC speakers were invited from 36 countries between 2014 and 2018 (Supplemental Material Table II), representing 6 continents. Speakers were invited for presentations in one or more of 21 categories, as seen in Figure 1. For the purpose of this study, the presentation categories were also combined into three groups: acute, in-hospital care; basic science; and stroke rehabilitation, recovery, prevention, and health services.

Figure 1.

Number of invited speakers to the ISC by sex and presentation category from 2014–2018. Males outnumber females in all categories except Nursing. Females represent the lowest proportion of speakers in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) and Other Neurocritical Management and Aneurysm categories. Presentation category information was missing for 531 presentations or 41%.

Session types included invited symposia, pre-conference symposia, debate, and case theater. Pre-conference symposia are held the day prior to the start of the main conference and are designed to explore certain topics related to stroke, synergizing with the main conference. The other sessions include basic and clinical science and are held during the main conference. Case theater explores best-practice with a patient presentation, debates employ field experts to discuss important clinical topics, and invited symposia are the large group talks at the main conference.

Frequency tables were provided for variables of interest (Tables 1–2). Percentages of males and females were reported in each category by year, degree, race, session type, institution continent, category, and number of invitations. Association between sex and these categorical variables was tested by Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. All data analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 software (Cary, NC).

Table 1.

Sex of invited speakers to the ISC by year. There was no difference among number of speakers by year by univariate analysis. Only 1.1% of all speakers over 5 years did not disclose sex information.

| Year | Females N=364 (%) |

Males N=919 (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 77 (29.4) | 185 (70.6) | 0.99 |

| 2017 | 80 (28.9) | 197 (71.1) | |

| 2016 | 71 (27.7) | 185 (72.3) | |

| 2015 | 68 (28.0) | 175 (72.0) | |

| 2014 | 68 (27.8) | 177 (72.2) |

Table 2.

Invited ISC speaker characteristics, all years combined.

| Speaker Characteristics | Females N=364 (%) |

Males N=919 (%) |

Univariate Analysis P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speaker Degree | |||

| Physicians | 170 (17.7) | 789 (82.3) | <0.0001 |

| Research Scientists | 59 (48.4) | 63 (51.6) | |

| Allied Health Professionals | 13 (81.3) | 3 (18.7) | |

| Midlevels | 64 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Nurses | 18 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| All Other Degrees | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | |

| Speaker Race | |||

| Alaskan Native/Native American | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0.0002 |

| Asian | 30 (20.0) | 120 (80.0) | |

| Black, not of Hispanic Origin | 6 (16.7) | 30 (83.3) | |

| White | 299 (32.7) | 616 (67.3) | |

| Hispanic | 6 (12.0) | 44 (88.0) | |

| Other/Two or More Races | 3 (15.0) | 17 (85.0) | |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Speaker Session Type | |||

| Case Theater | 1 (5.6) | 17 (94.4) | 0.0012 |

| Debate | 8 (13.1) | 53 (86.9) | |

| Invited Symposium | 322 (30.4) | 738 (69.6) | |

| ISC Pre-Conference Symposium | 33 (22.9) | 111 (77.1) | |

| Speaker Institution Continent | |||

| Africa | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | <0.0001 |

| Asia | 4 (8.3) | 44 (91.7) | |

| Australia | 15 (34.9) | 28 (65.1) | |

| Europe | 27 (14.4) | 161 (85.6) | |

| North America | 312 (31.6) | 676 (68.4) | |

| South America | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | |

| Speaker Category Group | |||

| Acute, In-hospital Care | 73 (19.0) | 311 (81.0) | 0.0002 |

| Basic Science | 38 (26.4) | 106 (73.6) | |

| Stroke Rehabilitation, Recovery, Prevention, and Health Services | 80 (33.5) | 159 (66.5) | |

Results:

There were 1086 individual invited speakers to the ISC with a total of 1283 presentations from 2014 to 2018. Notably, females represented 37.7% of all ISC attendees over those 5 years, and females represented 28% of ISC invited speakers (Table 1). There was no difference in sex distribution between years (p=0.99), therefore years were combined for analysis. Speakers were sometimes invited to speak in more than one session. Overall, 15.5% of speakers were invited more than once, and males were more likely invited as speakers two or more times (78.7%, p=0.01). Among the 164 speakers invited two or more times, only 21.3% were female.

Speaker sex was significantly different by degree category (p<0.0001). In the midlevel and nurse groups, females represented 100% of all invited speakers (Table 2). Allied health professionals represented the next highest proportion of females with 81.3%. The research scientist group was most balanced with 48.4% female invited speakers. In contrast, female physicians represented only 17.7% of speakers over 5 years. Degree data were missing for 111 invited speakers (8.7%).

Speaker sex was also significantly different according to race or ethnicity (p=0.0002). White females represented a large proportion of female invited speakers at 32.7% (Table 2). Underrepresented minority females represented the smallest proportions of invited speakers. Only 16.7% of Black invited speakers and 12.0% of Hispanic invited speakers were female. Between both sexes, Black and Hispanic invited speakers represented only 3.1% and 4.3%, respectively. Race or ethnicity data was missing for 124 invited speakers (9.6%).

Overall, speakers were invited for one of four session types: invited symposia (83%), pre-conference symposia (11%), debate (5%), and case theater (1%). Speaker sex was significantly different by session type (p=0.0012). The highest proportion of female speakers were in invited symposia (30.4%) and the lowest were in debate (13.1%) and case theater (5.6%) over the 5 years surveyed (Table 2).

When institution countries were combined by continent, there was a significant difference in institution continent by sex (p<0.0001). South America had the highest proportion of female speakers (50%). There were no female speakers from Africa, and only 8% of speakers from institutions in Asia were female (Table 2). Institution country data was missing for 16 invited speakers (1.2%).

With regard to presentation category, males outnumber females in all categories except for nursing. The proportion of female speakers was highest in nursing (86.4%) and was second highest in pediatric stroke (45.2%) categories. There were no female speakers in subarachnoid hemorrhage and other neurocritical care and aneurysm categories. Speaker category information was missing for 531 presentations or 41% of all presentations over 5 years.

When grouped, there was a significant difference in presentation category by sex (p=0.0002). The highest proportion of female speakers was in stroke rehabilitation, recovery, prevention, and health Services (33.5%). The lowest proportion of female speakers was in acute, in-hospital care (19%) (Table 2). By individual categories, the proportion of female speakers was highest in nursing (86.4%) and pediatric stroke (45.2%) and lowest in subarachnoid hemorrhage and other neurocritical care management and aneurysm with no female speakers (0%).

Discussion:

We found significant sex differences among invited speakers at the ISC from 2014 to 2018 by speaker degree, race, session type, institution continent, and presentation category. Females were less likely to be physicians, of underrepresented minority race or ethnicity, or from institutions in Asia or Africa, and females were less likely to be invited for debate or case theater presentations or presentations in acute, in-hospital care. Furthermore, we found that males were more likely to be invited as speakers more than once as compared to females.

Females represented only 28% of invited speakers at the ISC over the past 5 years. This is nearly 10% less than the proportion of females in conference attendance. When compared to the recently published proportion of practicing female neurologists (29.4%) and vascular neurology fellows (31.3%), the proportion is logical.1,2 However, given the rising number of females entering medicine and the large numbers of females in nursing and allied health professions, this proportion should be greater.6,7 Sex disparities have been identified at other major scientific conferences.10–21 In several studies, females represented less than one-third of invited speakers at major conferences, which is comparable to our findings.12, 14, 17, 19–21 In one study of five major critical care conferences, the sex differences among invited speakers were more pronounced among physicians than in nursing or other health professionals.19 This is similar to our finding that female physicians are underrepresented among speakers at the ISC.

Notably, White speakers represented the highest proportion of speakers overall and the highest proportion of female speakers at the ISC in the last 5 years. Black and Hispanic groups remain underrepresented. This seems to be reflective of the representation of these groups in the sciences in general. Biological sciences doctoral degrees awarded in the U.S. in 2016 were to 5.7% Hispanic and 3.1% Black graduates.23 Among all U.S. physicians in 2013, only 4.4% were Hispanic and 4.1% were Black.24 This racial disparity also seems to reflect the institution continent location as well. At the ISC, females from Africa and Asia are underrepresented. South America has the largest female representation, but this excludes Central America, including Mexico. Mexico had a large male representation of invited speakers (100%).

Females were less likely to be invited as speakers in the sessions for debate and case theater. These expert speakers are often identified as leaders in their field. This mirrors faculty ranks in neurology departments where men outnumber women at all ranks, with increasing disparity with advancing rank.25 By presentation category, females represented the smallest proportion of invited speakers in acute and intensive care medicine and neurosurgery. This may be reflective of the smaller female pool in these areas.26, 27 Currently only 8.4% of neurosurgeons and 26.1% of critical care physicians are female.28 Nursing is traditionally a female-dominated field, where the sex trend is reversed.6

Authorship of original research is viewed as an objective measure of one’s scientific achievement, and this may negatively influence the number of females invited as speakers at a major conference like the ISC.29 The sex gap in proportion of females among higher academic rank positions in neurology is reflected among invited speakers at the ISC.3, 25 It is not simply an underrepresentation at the conference alone but a “trickle-down” effect from the hierarchy of academic institutions.

There are other possible reasons for the described sex disparities. The cause of this “leaky pipeline” is likely multifactorial, including overt discrimination, intrinsic biases, inadequate numbers of female role models and mentors, and the difficulties of balancing work and family life.10, 11, 30 Traveling to a conference poses its own set of limitations, including availability of childcare and facilities for nursing.31

Studies of major conferences in other specialties have helped address issues of sex disparity. The acknowledgement of the trends can increase female involvement, which has been shown by other studies of other conferences.10, 22 Including females on the organizing board of the conference, developing a speaker policy, hosting training programs geared for females, collecting and evaluating the conference sex data and creating a family-friendly conference environment are ways to improve female representation at scientific conferences.10, 15–18, 22, 32, 33

If there is a paucity of diversity to begin with, we cannot improve diversity at scientific conferences. The basis of female participation starts from the beginning of training and study. There is a recent increase in females entering medical school, and the proportion of women participating in research and academic advancement will likely increase. This is congruent with increasing numbers of racial and ethnic minority groups entering medical school.34 Leaders in the field should support a culture of diversity, particularly among junior faculty.35 Department leaders and mentors should be aware of the growing opportunities for underrepresented groups, including funding for research and career development opportunities.

There are a number of limitations in our study. This study only evaluated the past 5 years with no trend identified, and there may be trends from years past. It is possible that more female speakers declined to participate. We do not have that information. A large proportion of the speaker presentation categories were missing, about 41%, which leaves room for bias. By combining by institution continent for analysis, we may have missed sex disparities in certain countries. Most invited speakers are from the United States, which limits interpretation of comparisons among other countries. International travel likely poses its own limitations for invited speakers and may differentially impact males as opposed to females.

There are several strengths to this study. Only 1.1% of speakers did not disclose sex, so we have captured the scope of the speaker sex gap overall. Sex disparities among speakers at scientific conferences has been studied in other specialties, but this gap has not been studied among speakers at the ISC.

Conclusions:

The purpose of this study is to draw attention to the fact that women are underrepresented as speakers at this major scientific conference. There are trends in certain areas of research where females are less likely invited speakers compared to males, in fields like critical care and neurosurgery, where there is a smaller female pool. Moreover, racial minority females and female physicians are less often invited as speakers. Increased efforts are warranted to improve sex differences among speakers at the ISC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Sources of Funding: Authors were supported by the following National Institutes of Health grants 5T32NS007412–20 (Fournier), 1R03CA219450 (Zhu), R37 NS096493 (McCullough).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References:

- 1.ACGME Residents and Fellows by Sex and Specialty, 2017 2018. https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/492576/2-2-chart.html. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- 2.Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2017 2018. https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/492560/1-3-chart.html. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- 3.U.S. Medical School Faculty by Sex, Rank, and Department, 2017 2018. https://www.aamc.org/download/486102/data/17table13.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- 4.Pell AN. Fixing the leaky pipeline: women scientists in academia. J Anim Sci 1996;74:2843–2848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alper J. The pipeline is leaking women all the way along. Science 1993;260:409–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smiley RA, Lauer P, Bienemy C, Berg JG, Shireman E, Reneau KA, et al. The 2017 National Nursing Workforce Survey. Journal of Nursing Regulation 2018;9:S1–S88 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beagan BL, Fredericks E. What about the men? Gender parity in occupational therapy: Qu’en est-il des hommes? La parite hommes-femmes en ergotherapie. Can J Occup Ther 2018;85:137–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sex of Nurse Educators by Employment Status, 2015 2015. http://www.nln.org/docs/default-source/newsroom/nursing-education-statistics/sex-of-nurse-educators-by-employment-status-2015-(pdf).pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- 9.2012–2013 Fact Sheet, Physical Therapist Education Programs 2014. http://www.capteonline.org/uploadedFiles/CAPTEorg/About_CAPTE/Resources/Aggregate_Program_Data/Archived_Aggregate_Program_Data/CAPTEPTAggregateData_2013.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- 10.Casadevall A. Achieving Speaker Gender Equity at the American Society for Microbiology General Meeting. MBio 2015;6:e01146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kafer J, Betancourt A, Villain AS, Fernandez M, Vignal C, Marais GAB, et al. Progress and Prospects in Gender Visibility at SMBE Annual Meetings. Genome Biol Evol 2018;10:901–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carley S, Carden R, Riley R, May N, Hruska K, Beardsell I, et al. Are there too few women presenting at emergency medicine conferences? Emerg Med J 2016;33:681–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casadevall A, Handelsman J. The presence of female conveners correlates with a higher proportion of female speakers at scientific symposia. MBio 2014;5:e00846–00813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davids JS, Lyu HG, Hoang CM, Daniel VT, Scully RE, Xu TY, et al. Female Representation and Implicit Gender Bias at the 2017 American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons’ Annual Scientific and Tripartite Meeting. Dis Colon Rectum 2019;62:357–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debarre F, Rode NO, Ugelvig LV. Gender equity at scientific events. Evol Lett 2018;2:148–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofstadter-Thalmann E, Dafni U, Allen T, Arnold D, Banerjee S, Curigliano GMD, et al. Report on the status of women occupying leadership roles in oncology. ESMO Open 2018;3:e000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalejta RF, Palmenberg AC. Gender Parity Trends for Invited Speakers at Four Prominent Virology Conference Series. J Virol 2017;91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein RS, Voskuhl R, Segal BM, Dittel BN, Lane TE, Bethea JR, et al. Speaking out about gender imbalance in invited speakers improves diversity. Nat Immunol 2017;18:475–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta S, Rose L, Cook D, Herridge M, Owais S, Metaxa V. The Speaker Gender Gap at Critical Care Conferences. Crit Care Med 2018;46:991–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroeder J, Dugdale HL, Radersma R, Hinsch M, Buehler DM, Saul J, et al. Fewer invited talks by women in evolutionary biology symposia. J Evol Biol 2013;26:2063–2069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shishkova E, Kwiecien NW, Hebert AS, Westphall MS, Prenni JE, Coon JJ. Gender Diversity in a STEM Subfield - Analysis of a Large Scientific Society and Its Annual Conferences. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2017;28:2523–2531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin JL. Ten simple rules to achieve conference speaker gender balance. PLoS Comput Biol 2014;10:e1003903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2015. Special Report NSF 17–306 2016. www.nsf.gov/statistics/2017/nsf17306/. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- 24.U.S. Physicians by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2013 2014. http://www.aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org/section-ii-current-status-of-us-physician-workforce/index.html#fig1. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- 25.McDermott M, Gelb DJ, Wilson K, Pawloski M, Burke JF, Shelgikar AV, et al. Sex Differences in Academic Rank and Publication Rate at Top-Ranked US Neurology Programs. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:956–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benzil DL, Abosch A, Germano I, Gilmer H, Maraire JN, Muraszko K, et al. The future of neurosurgery: a white paper on the recruitment and retention of women in neurosurgery. J Neurosurg 2008;109:378–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venkatesh B, Mehta S, Angus DC, Finfer S, Machado FR, Marshall J, et al. Women in Intensive Care study: a preliminary assessment of international data on female representation in the ICU physician workforce, leadership and academic positions. Crit Care 2018;22:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.2018 AAMC Physician Specialty Data Report 2019. https://www.aamc.org/download/493090/data/2018-aamc-physician-specialty-data-report.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- 29.Jagsi R, Guancial EA, Worobey CC, Henault LE, Chang Y, Starr R, et al. The “gender gap” in authorship of academic medical literature--a 35-year perspective. N Engl J Med 2006;355:281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones TM, Fanson KV, Lanfear R, Symonds MR, Higgie M. Gender differences in conference presentations: a consequence of self-selection? PeerJ 2014;2:e627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dean C, Osborn M, Oshlack A, Thornton J. Women in science. Genome Biol 2012;13:148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sardelis S, Drew JA. Not “Pulling up the Ladder”: Women Who Organize Conference Symposia Provide Greater Opportunities for Women to Speak at Conservation Conferences. PLoS One 2016;11:e0160015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sunga KL, Kass D. Taking the stage: a development programme for women speakers in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 2019;36:199–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.2017 Applicant and Matriculant Data Tables 2017. https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/5c/26/5c262575-52f9-4608-96d6-a78cdaa4b203/2017_applicant_and_matriculant_data_tables.pdf. Accessed April 30, 2019.

- 35.Hamilton RH. Enhancing diversity in academic neurology: From agnosia to action. Ann Neurol 2016;79:705–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.