Abstract

We designed, synthesized and identified a novel nucleoside derivative, 4’-C-cyano-7-deaza-7-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine (CdFA), which exerts potent anti-HBV activity (IC50 ~26 nM) with favorable hepatocytotoxicity (CC50~56 μM). Southern blot analysis using wild-type HBV (HBVWT)-encoding-plasmid-transfected HepG2 cells revealed that CdFA efficiently suppresses the production of HBVWT (IC50=153.7 nM), entecavir (ETV)-resistant HBV carrying L180M/S202G/M204V substitutions (HBVETVR; IC50=373.2 nM), and adefovir dipivoxil (ADV)-resistant HBV carrying A181T/N236T substitutions (HBVADVR; IC50=192.6 nM), whereas ETV and ADV were less potent against HBVETVR and HBVADVR (IC50: >1,000 and 4,022.5 nM, respectively). Once-daily peroral administration of CdFA to human-liver-chimeric mice over 14 days (1 mg/kg/day) comparably blocked HBVWT and HBVETVR viremia by 0.7 and 1.2 logs, respectively, without significant changes in body-weight or serum human-albumin levels, although ETV only slightly suppressed HBVETVR viremia (CdFA vs ETV; p=0.032). Molecular modeling suggested that ETV-TP has good nonpolar interactions with HBVWT reverse transcriptase (RTWT)’s Met204 and Asp205, while CdFA-TP fails to interact with Met204, in line with the relatively inferior activity against HBVWT of CdFA compared to ETV (IC50: 0.026 versus 0.003 nM). In contrast, the 4’-cyano of CdFA-TP forms good nonpolar contacts with RTWT’s Leu180 and RTETVR’s Met180, while ETV-TP loses interactions with RTETVR’s Met180, explaining in part why ETV is less potent against HBVETVR than CdFA. The present results show that CdFA exerts potent activity against HBVWT, HBVETVR and HBVADVR with enhanced safety and that 7-deaza-7-fluoro modification confers potent activity against drug-resistant HBV variants and favorable safety, shedding light to further design more potent and safer anti-HBV nucleoside analogs.

Keywords: HBV, anti-HBV drugs, drug resistance, entecavir, adefovir, nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors

1. Introduction

Presently two-hundred-fifty-seven million people are chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and more than 887,000 people die every year due to complications of HBV infection including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)(World Health Organization., 2017).

Oral nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors (NRTIs) efficiently suppress HBV replication by directly targeting the activity of the HBV-RT and treatment with NRTIs has been shown to hold disease progression and reduce the eventual risk of development of hepatocellular carcinoma (Menéndez-Arias et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2016). However, due to its inefficacy to terminate the covalently closed circular DNA, NRTIs treatment is required to be given over quite a long period of time, probably over a life-time. With an estimated mutation rate of 1.4–3.2×10−5 nucleotide substitutions per site and replicative cycle and an estimated production of ~1011 HBV virus particles per day if not treated (Orito et al., 1989; Nowak et al., 1996), HBV’s acquisition of antiviral drug resistance remains as one of the challenges in successful long term therapy of chronic HBV infection, although it is noteworthy that ETV resistance has been known to be clinically significant mostly in patients carrying pre-existing 3TC resistance mutations, and TFV resistance is generally clinically negligible. Both ETV and TDF (the prodrug to TFV) are now generic and have nearly totally displaced the earlier nucleos(t)ide analogs such as 3TC.

We have previously reported that two nucleoside analogs, 4’-C-cyano-2’-deoxyguanosine (CdG) and 4’-C-cyano-2-amino-2’-deoxyadenosine (CAdA) exert potent activity in suppressing the replication of wild-type HBV strains (HBVWT), an ETV-resistant HBV (HBVETVR) and an ADV-resistant HBV (HBVADVR) in vitro and in human-liver-chimeric mice (Takamatsu et al., 2015). However, both compounds proved to be highly cytotoxic compared to other currently available anti-HBV therapeutics and were dropped from further development. On the basis of the structural findings obtained from our previous studies, we designed, synthesized and identified a novel 4’-modified nucleoside with improved properties, 4’-C-cyano-7-deaza-7-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine (CdFA).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells, viruses, and antiviral agents

HepG2.2.15 cells were cultured with DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA) and 1% G-418 solution (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). HepG2 cells were cultured with DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA). The MT-2 cells were grown in RPMI 1640-based culture medium supplemented with 10% FCS. HIV-1LAI was also used for the anti-HIV drug susceptibility assay. PXB cells were cultured as previously described (Higashi-Kuwata et al., 2019). Two recombinant infectious HBV clones, HBVWTCe and HBVETVR, were generated as previously described (Takamatsu et al., 2015; Hayashi et al., 2015) and used as the sources of infectious virions in the present study. CdFA was newly designed and synthesized, while CdA and CdG were synthesized as previously described (Kohgo et al., 2004; Takamatsu et al., 2015). The origins of entecavir (ETV), lamivudine (3TC or LAM), adefovir pivoxil (ADV), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) employed in the present study and the synthetic method and characterizing data of CdFA are described in Supplementary material.

2.2. Anti-HBV assay, anti-HIV-1 assay, and cytotoxicity assay

Anti-HBV assays were conducted using HepG2.2.15 cell line as described previously (Higashi-Kuwata et al., 2019). Briefly, HepG2.2.15 cells (4×103 cells) were seeded in 96-well microtiter cell culture plates together with various concentrations of a test compound. On day 14, DNA was extracted from the cells using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and was resolved in 100 μl 1 × TE buffer. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted using the genesig® standard Kit for HBV core protein region (Primerdesign™Ltd, Southampton, UK).

Anti-HIV-1 assay was conducted as previously described (Kodama et al., 2001; Aoki et al., 2019). In brief, MT-2 cells were exposed to an HIV strain at hundred 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50). After viral exposure, the cell suspension (103 cells/100 μL) was plated in each well of a 96-well flat microtiter culture plate containing various concentrations of a test compound. After incubation for 7 days, the number of viable cells in each well was measured using Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). The potency of HIV-1 inhibition by the compound was determined based on its inhibitory effect on virally-induced cytopathicity in MT-2 cells as 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values. Cytotoxicity of the compound in PXB cells was also determined. PXB cells were plated in a 96-well plate at a density of 7×104 in 200 μL/well and were continuously exposed to various concentrations of a test compound throughout the entire period of the culture. The number of viable cells in each well was determined using Cell Counting Kit-8 as 50% cytotoxicity concentration (CC50) values. More detailed procedures are given in Supplementary material.

2.3. HBV-DNA transfection and detection of core-associated HBV-DNA from transfected cells using Southern blot hybridization

Plasmids carrying the 1.24-fold HBV genomes of a wild-type genotype Ce strain (HBVWTCe), entecavir-resistant strain carrying L180M/S202G/M204V substitutions (HBVETVR), or adefovir-resistant strain carrying A181T/N236T substitutions (HBVADVR) were constructed for in vitro study as previously described (Hayashi et al., 2015). Five million HepG2 cells were plated onto a 6-well cell culture plate, and 24 hours later, cells were transfected with 2.5 μg of the plasmid using Fugene HD transfection reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The transfected cells were then added with different concentrations of each of test compounds in 5–6 hours after transfection, and then harvested after further 6 days. Briefly, capsid associated HBV-DNA was extracted and Southern hybridization performed as previously described (Hayashi et al., 2015). More detailed procedures are given in Supplementary material.

2.4. HBV infection of human-liver-chimeric mice

Severe combined immunodeficiency mice transgenic for the urokinase-type plasminogen activator gene (uPAwild/+/SCID+/+ mice) with the liver replaced with human hepatocytes (human-liver-chimeric mice) were purchased from Phoenix Bio Co., Ltd. (Hiroshima, Japan). The human serum albumin was measured with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using commercial kits (Eiken Chemical Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). HBV-DNA sequences spanning the S gene were amplified using real-time PCR employing the method by Abe et al (Abe A et al., 1999). Two recombinant infectious HBV clones, HBVWT and HBVETVR, were used in this study. Seven to 14 weeks after inoculation of HBV-infected mice were treated with saline or ETV or CdFA at a dose of 1 mg/kg, once a day over 14 days. More detailed procedures are given in Supplementary material.

2.5. Statistical analysis of the changes in the viral loads, body weights and serum human albumin levels of treated mice

The changes in the viral loads, body weights, and serum human albumin levels from the day 0 level of each mouse treated with saline, ETV or CdFA were compared using repeated measures analysis of variance with two-tailed P values not corrected for multiple comparisons.

2.6. Molecular modeling

To gain insights into the atomic details of the inhibitory mechanism of ETV and CdFA, we built initial molecular models of the ternary complexes of HBV-RTWT and RT containing three amino acid substitutions, with primer-templates and in complex with ETV-triphosphates (TP) using homology modeling, semi-empirical quantum chemical methods and molecular dynamics as previously described (Takamatsu et al., 2015). Structural manipulations to generate CdFA-TP as well as to generate different mutated RT residues were performed using Maestro version 10.7.015 (Schrödinger, LLC, New York). Correct bond orders of the residues, including zero-order bonds from the Mg2+ to the phosphate groups were assigned, and the termini were capped. Restrained minimization using OPLS3 force field was performed. A cut-off distance of 3.0 Å between a polar hydrogen and an oxygen or nitrogen atom, a minimum donor angle of 60° between D-H-A and a minimum acceptor angle of 90° between H-A-B was used to define the presence of hydrogen bonds (D, A, B are donor, acceptor, and atom connected to acceptor, respectively). Connolly molecular surfaces for the inhibitors and selected RT residues from the active site were generated using a water sphere with a radius of 1.4Å as a probe. Structural figures were generated using Maestro version 10.7.015 (Schrödinger, LLC, New York).

3. Results

3.1. CdFA suppresses the replication of HBV at subcytotoxic concentrations

Based on the structure-activity relationships learned from our previous study (Takamatsu et al., 2015), we designed and synthesized approximately 220 novel nucleoside analogs including 4’-cyano moiety-containing nucleosides. We examined those nucleoside analogs for their ability to block a wild type HBV genotype D (HBVWTD) production in HepG2.2.15 cells using real-time HBV-PCR as described in the Materials and Methods section. Among them, we identified 4’-C-cyano-2’-deoxyadenosine (CdA) and 4’-C-cyano-7-deaza-7-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine (CdFA), which were highly potent in reducing HBVWTD DNA levels in HepG2.2.15 cells. Structurally, CdA and CdFA contain 4’-cyano moiety, while the former has an adenine as its base but the latter has 7-deaza-7-fluoro-2-aminopurine (Fig. 1). We compared their anti-HBV activity with five FDA-approved NRTIs (3TC, ADV, ETV, TDF, and TAF), and CdG against the production of HBVWTD in HepG2.2.15 cells and infection of MT-2 cells by HIV-1LAI. As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2, all these eight NRTIs effectively reduced the production of HBVWTD DNA in HepG2.2.15 cells. The order of the magnitude of anti-HBV activity was: CdG>ETV>CdFA>3TC>TAF>CdA>TDF>ADV as compared with their half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50)(Table 1). CdG proved to be the most potent agent to block HBVWTD production in HepG2.2.15 cells (IC50=0.0005 μM) in line with our previous data (Takamatsu et al., 2015), followed by ETV and CdFA, both of which were also highly potent against HBV with IC50 values of 0.003 and 0.026 μM, respectively. Although CdFA turned out to be more potent against HBVWTD than TDF by 7.7-fold in HepG2.2.15 cells (Table 1), it should be noted that TDF is a prodrug that can be readily converted to TFV and activated in metabolically highly active hepatocytes such as primary human hepatocytes and has been shown to be highly active against various HBV. Of note, CdFA showed significantly less hepatocytotoxicity in PXB cells than CdA and CdG (CC50 values: 55.9, 5.4 and 0.37 μM, respectively), yielding more favorable selectivity index (S.I.) of approximately 2,150, compared to CdA and CdG with S.I. values of 82 and 740, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Structures of entecavir (ETV), 4’-C-cyano-2’-deoxyadenosine (CdA), and 4’-C-cyano-7-deaza-7-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine (CdFA).

Table 1.

Activity of various NRTIs against HBV and HIV-1 and their cytotoxicity

| IC50 (μM) against: | CC50 (μM) in: | S.I. with: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | HBVWTD | HIV-1LAI | PXB cells | Anti-HBV |

| 3TC | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.66 ± 0.15 | > 100 | >2,000 |

| ADV | 0.88 ± 0.15 | 0.66 ± 0.20 | 71.5 ± 19.3 | 81 |

| ETV | 0.003 ± 0.002 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 251.5 ± 37.5 | 83,833 |

| TDF | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 33.4 ± 10.9 | 167 |

| TAF | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.004 ± 0.002 | 5.7 ± 1.9 | 114 |

| CdG | 0.0005 ± 0.0001 | 0.0006 ± 0.0001 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 740 |

| CdA | 0.066 ± 0.003 | 0.094 ± 0.004 | 5.4 ± 1.5 | 82 |

| CdFA | 0.026 ± 0.003 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 55.9 ± 5.7 | 2,150 |

Anti-HBV activity of each compound was determined using HepG2.2.15 cells, while anti-HIV-1 activity was determined using HIV-1LAI cells. Each assay was conducted in duplicate or triplicate. The values represent mean values (± 1 S.D.) from two or three independent experiments. The selectivity index (S.I.) for anti-HBV activity was determined using the following formula: CC50 value of a compound in PXB cells/IC50 value of the compound to suppress the synthesis of HBV DNA in HepG2.2.15 cells.

Fig. 2. Anti-HBV activity of CdFA and various nucleos(t)ide analogs.

Suppression of the synthesis of HBV-DNA in HepG2.2.15 cells by 3TC, ADV, ETV, TDF, TAF, CdG, CdA and CdFA is illustrated. Intracellular HBV-DNA amounts were determined using real-time HBV-PCR and are shown as percent controls compared to that without test compound (control=100%). All the values are shown as the average values obtained from two or three independent experiments.

3.2. CdFA potently suppresses the replication of HBVWT but not that of HIV-1LAI

We then examined whether CdA, CdG and CdFA also exerted antiviral activity against HIV-1LAI (Table 1). When examined with the methyl-thiazol tetrazolium (MTT) assay using MT-2 cells, 2 of the 5 reference drugs, TDF and TAF, which are presently in clinical use for treating HIV-1LAI infection and AIDS, exerted potent activity against HIV-1LAI with IC50 values of 0.03 and 0.004 μM, respectively, while 3TC, ADV and ETV were much less active against HIV-1LAI (IC50 values of 0.66, 0.66 and 1.0 μM, respectively) (Table 1). Interestingly, while CdG and CdA were comparably potent against HBVWT and HIV-1LAI, CdFA was found to be potent against HBVWT, but only moderately active against HIV-1LAI (IC50 values: 0.026 and 0.88 μM, respectively) (Table 1). CdFA was also moderately active against HIV-1 (Table 1). In this regard, although we have not experimentally demonstrated that CdFA actually targets the RT of HBV, considering that both HIV-1 and HBV have RT that is targeted by certain NRTIs, the activity of CdFA against HIV-1 per se strongly suggests that CdFA is activated to its TP form and blocks the activity of HBV-RT.

3.3. CdFA strongly suppresses the production of HBVWTCe, HBVETVR, and HBVADVR in vitro

We subsequently asked whether CdFA blocked the replication of wild type HBV genotype Ce (HBVWTCe), ETV-resistant HBV (HBVETVR), and ADV-resistant HBV (HBVADVR) using Southern blotting assay (Table 2 and Fig.3). HepG2 cells were first transfected with an HBVWTCe-encoding plasmid, the cells were cultured in the presence of each test compound, and the intensity of the signal for a single-stranded HBVCe-DNA (ssDNA) on the membrane was quantified (Fig. 3). The signal of ssDNA was clearly observed in the presence of 1 nM ETV (Fig. 3). However, the signal was weakened in a dose-dependent manner and was virtually completely lost in the cells exposed to 100 nM of ETV and beyond. As shown in Table 2, the IC50 values of ETV and ADV against HBVWTCe were 4.1±0.3 and 2043.5±858.6 nM from two independent assays, respectively. As examined under the same conditions, the activity of CdFA against HBVWTCe (IC50=153.7±15.1 nM) was lesser than that of ETV but greater than ADV. These Southern blotting assay data well corroborated the anti-HBV activity data obtained with the qPCR system (Table 1 and Fig.2).

Table 2.

In vitro susceptibility of HBVWT, HBVETVR, and HBVADVR to ETV, ADV and CdFA in HBV-plasmid-transfected HepG2 cells.

| IC50 (nM) against | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | HBVWTCe | HBVETVR | HBVADVR |

| ETV | 4.1 ± 0.3 | >1000 (>250) | 1.9± 2.6 (0.5) |

| ADV | 2043.5 ± 858.6 | 2867.7 ±3897.6 (1.4) | 4022.5 ± 923.7 (2.0) |

| CdFA | 153.7 ± 15.1 | 373.2 ± 63.7 (2.4) | 192.6 ± 13.7 (1.3) |

The IC50 values were obtained using Southern blotting assay. All IC50 values represent average values (±1 S.D.) from two independent experiments. The numbers in parentheses represent the fold change of the IC50 value of a compound compared to that against HBVWT.

Fig. 3. Reduction of HBV-DNA synthesis by various NRTIs in plasmid-transfected HepG2 cells as assessed using Southern blot analysis.

HepG2 cells were transfected with various HBV-encoding plasmids and cultured for 6 days in the presence of each compound, and DNA extracted from those cells was subjected to Southern blot analysis. For each compound, the relative amount of single-stranded replicative intermediate DNA (ssDNA) in the cells was determined using a chemiluminescence detection system (LAS 4000 mini biomolecular imager; GE Healthcare). Based on the density of signals observed, the IC50 values, at which 50% decrease of intracellular ssDNA was achieved and compared with those in the cells unexposed to test compound, were determined using the Forecast function of Microsoft Excel software. The location of ssDNA (1.5kb) is indicated with arrows. All cells were cultured in the presence of 0.1% DMSO, irrespective of exposure to test compound or the concentrations.

We also examined whether CdFA suppressed the production of ETV- and ADV-resistant HBV variants (HBVETVR and HBVADVR, respectively). ETV failed to block HBVETVR production even at the highest concentration (1,000 nM) and its IC50 value turned out to be >1,000 nM (Fig. 3 and Table 2). However, ETV effectively blocked the production of HBVADVR and its IC50 value was as low as 1.9 nM. The activity of ADV against HBVWTCe was moderate (IC50=2,043.5 nM) as compared to ETV and ADV also only moderately blocked the production of HBVETVR (IC50=2,867.7 nM). ADV was further less active against HBVADVR with an IC50 value of 4,022.5 nM. By contrast, CdFA effectively blocked both HBVETVR and HBVADVR with IC50 values of 373.2±63.7 and 192.6±13.7 nM, respectively (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Taken together, these results demonstrate that CdFA is effective in suppressing the production of not only HBVWT but also HBVETVR and HBVADVR.

3.4. CdFA blocks the production of HBV in WTCe- and HBVETVR-infected human-liver-chimeric mice

We then examined whether CdFA blocked the production of HBVWTCe and HBVETVR in uPAwild/+/SCID+/+ mice. In all nine mice inoculated with HBVWTCe, the number of HBVWTCe DNA copies in plasma continued to rise, plateauing at 5–24×108 copies/mL following the inoculation (Fig. 4–A). Based on the anti-HBV data obtained with the present qPCR assay (Table 1), the present Southern blot assay (Fig. 3), as well as the dose chosen in our previous studies (Takamatsu et al., 2015, Higashi-Kuwata et al., 2019), a 1mg/kg dose of CdFA was chosen for PXB mice in this study. The mice were orally gavaged with ETV or CdFA (both at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL in saline) or saline through oral sonde so that the dose administered resulted in 1 mg/kg/day for 14 days. In the ETV group, the viremia levels significantly went down by day 7 of ETV administration and further viremia reduction occurred to the lowest by the average of 2.2 log10 copies/mL by day 14) (Figure 4–A, upper middle panel). There was a significant reduction of HBVWTCe DNA amounts by the average of 0.5 log10 copies/mL by 3 days after CdFA treatment was begun and the amounts continued to decrease by the end of the treatment, reducing the amounts by an average of 0.7 log10 copies/mL as assessed on day 14 (Fig. 4–A, upper right panel). In the control “no agent” mice, no reduction of HBVWTCe was observed (Fig.4–A, upper left panel). By contrast, a significant reduction in the amounts of HBVWTCe DNA was seen in mice receiving ETV and CdFA compared to the no agent mice (p<0.0001 and p=0.0019, respectively); although the HBVWT viremia reduction in mice receiving CdFA was significantly less than in mice receiving ETV (p<0.0001).

Fig. 4. Antiviral activity of NRTIs against HBVWT and HBVETVR in human liver-chimeric mice.

(A) Following the inoculation of human liver-chimeric mice with HBVWT (upper panels) or HBVETVR (lower panels), saline (as no agent), ETV or CdFA was intragastrically administered for 14 days (1 mg/kg/day). Serum HBV-DNA levels following indicated treatments were determined with real-time PCR (n=2–4 per group). Each line illustrates the changes in HBV-DNA levels in an individual mouse. Note that CdFA significantly reduced HBVWT viremia compared to no agent controls (p=0.0019), while its reduction levels were lesser than those in ETV-receiving mice (p<0.0001). CdFA also significantly reduced HBVETVR viremia more than in the no agent control mice (p=0.0044). (B) Serum human albumin levels and body weights of each mouse were monitored. Each line denotes an individual mouse. There are no significant differences in albumin levels between saline-, ETV- and CdFA-receiving groups, while the ETV group lost slightly more weight than the other two groups (p=0.032 vs. no agent, p=0.017 vs. CdFA).

Next, we examined whether CdFA suppressed the production of HBVETVR in mice. In those mice, the amounts of HBVETVR DNA reached 4.9×105-2.4×108 copies/mL and the administration of 1 mg/kg/day of ETV, CdFA or saline was implemented. As shown in Fig. 4–A, a rather slight increase in viremia was observed in the no agent mice (lower left panel). ETV, at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day, caused a significant reduction in HBVETVR viremia levels (by the average of 0.5 log10 copies/mL by 14 days, p=0.03). However, CdFA much more potently reduced the HBVETVR viremia by the average of 0.6 log10 copies/mL by 3 days after CdFA treatment was begun. The reduction was further deepened by the average of 1.2 log10 copies/mL by day 14 of treatment (p=0.0044; lower right panel). CdFA more potently suppressed the HBVETVR viremia as compared to ETV (p=0.032).

3.5. CdFA caused no significant changes in body weights or serum human albumin levels in human-liver-chimeric mice

Serum human albumin (h-albumin) levels and body weights of three mouse groups were monitored throughout the treatment (Fig. 4–B). In the HBVWTCe-inoculated mice, one mouse in the no agent group had stable weight and one mouse in the CdFA group experienced weight increase, but the other seven mice had decreases in their weights compared to those on day 0. The ETV group had slightly greater decreases than the no agent (p=0.032) and CdFA groups (p=0.017). The ETV-receiving mice showed no apparent changes in weight, albeit fewer mice were analyzed. Overall, there were no significant differences in body weights among the three groups. No changes in h-albumin levels were observed in HBVWT- or HBVETVR-infected mice regardless of treatment (Fig. 4–B).

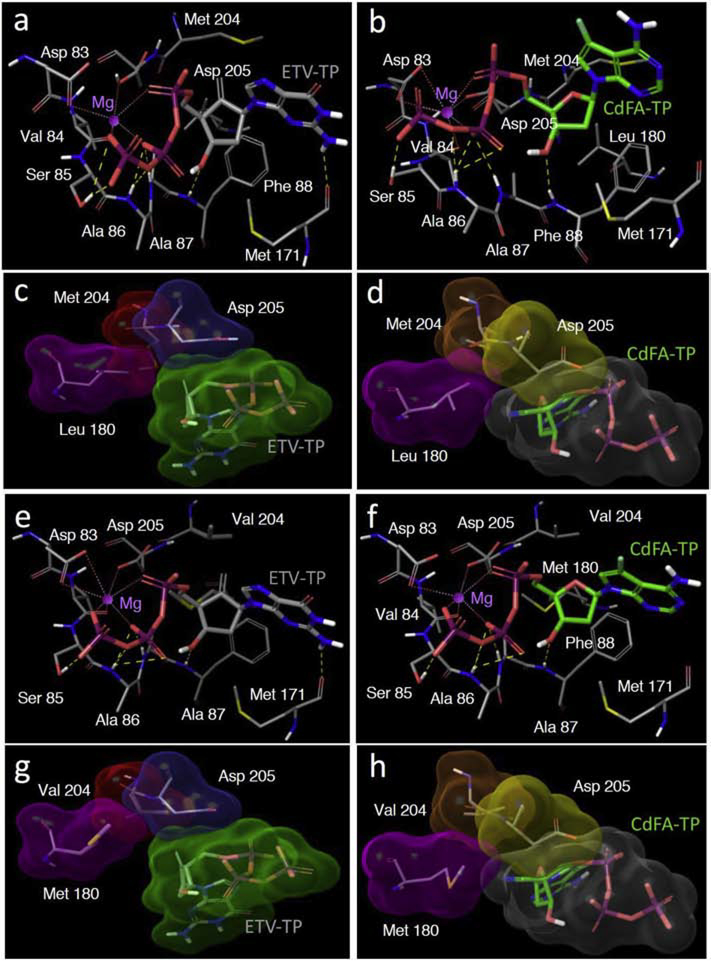

3.6. Structural analysis of CdFA-TP interactions with HBV-RTWT and HBV-RTETV-R

Finally, we built and analyzed molecular models of CdFA-TP and ETV-TP’s interactions with HBV-RTWT and HBV-RTETVR (Fig. 5). As described in the Materials and Methods section, the sequence similarity of HBV-RT with HIV-RT was used, and homology model building techniques followed by structural optimizations were used to build the models. ETV-TP is projected to form multiple polar interactions with HBV-RTWT. The hydroxyl group of its sugar moiety is projected to form hydrogen bond interactions with the backbone NH of Phe88 (Fig. 5–a). The triphosphate group of CdFA-TP coordinates with the magnesium ion and together forms polar interactions with Asp83, Val84, Ser85, Ala86, and Ala87 (Fig. 5–b). The base of ETV-TP also forms a hydrogen bond with Met171. CdFA-TP has all these polar interactions with RTWT except for Met171 (Fig. 5–b). We also analyzed the nonpolar interactions by looking at the Connolly surface interactions of the two inhibitors with the key residues in the active site (Fig. 5–c, d). ETV-TP is projected to have good Connolly surface interactions with Met204 and Asp205 (Fig. 5–c). CdFA-TP also has good Connolly surface contacts with Asp205 but doesn’t have as tight interactions with Met204 as does ETV-TP (Fig. 5–d). This difference in non-polar interactions along with the additional hydrogen bond with Met171 appears to be partly responsible for the relatively greater anti-HBV potency against HBVWTD and HBVWTCe of ETV-TP over CdFA-TP.

Fig. 5. Molecular models of the polar and nonpolar interactions between HBV-RTs and ETV-TP or CdFA-TP.

The polar (yellow dotted lines) and nonpolar (Connolly surface) interactions of ETV-TP (gray carbons) with RTWT are shown in Panels a and c, respectively, while those with RTETV-R are shown in Panels e and g, respectively. The polar and nonpolar interactions of CdFA-TP (green carbons) with RTWT are shown in Panels b and d, respectively, while those with RTETV-R are shown in Panels f and h, respectively. The Connolly surfaces for ETV-TP and CdFA-TP are shown in green and gray, respectively. The surfaces for residues 180, 204 and 205 for ETV-TP interactions are shown in magenta, red, and cyan, respectively, while those for residues 180, 204 and 205 for CdFA-TP interactions are shown in magenta, orange, and yellow, respectively. Nitrogen, oxygen, phosphor, fluorine and polar hydrogen atoms are shown in blue, red, purple, light blue and white, respectively. Non-polar hydrogens are not shown for clarity. The magnesium ion is shown as a magenta sphere. The figures were generated with Maestro (version 10.7.015, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY).

We then analyzed the interactions of ETV-TP and CdFA-TP with HBV-RT, in which three amino acid substitutions associated with HBV’s resistance to ETV (L180M/S202G/M204V) have been introduced (RTETV-R). The polar interactions of both ETV-TP and CdFA-TP with RTETV-R are similar to those observed for RTWT (Fig. 5–e and -f). The most striking difference in nonpolar interactions arises from the interactions of residue 180 with the two inhibitors. The 4′-cyano group of CdFA-TP makes effective contact with Leu180 of RTWT (Fig. 5–d), and this contact is maintained with its substitution to Met180 for RTETV-R (Fig. 5–h). However, the lack of the 4′-cyano in ETV-TP results in a drastic loss of interactions with Met180 of RTETV-R (Fig. 5–g) compared to its interactions with Leu180 of RTWT (Fig. 5–c). The difference in these interactions with residue 180 may explain why CdFA exhibits only a modest decrease in anti-HBV potency (2.4-fold) compared to the profound loss of potency (>250-fold) that ETV experiences against HBVETV-R, relative to HBVWTCe (Fig. 3; Table 2).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that two novel 4’-modified nucleoside analogs, 4’-C-cyano-2’-deoxyadenosine (CdA) and 4’-C-cyano-7-deaza-7-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine (CdFA) are active against HBVWT (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Since CdA was found to be rather toxic, we further focused anti-HBV profiles of CdFA. CdFA is also active against entecavir (ETV)-resistant HBV (HBVETVR) and adefovir dipivoxil (ADV)-resistant HBV (HBVADVR) in vitro (Fig. 3 and Table 2), and efficiently suppressed HBV-DNA titer of HBVETVR in human-liver-chimeric mice (Fig. 4A).

CdFA is structurally related not only to CdA (Fig. 1), but also to CAdA and CdG (Takamatsu et al., 2015). All these four nucleoside analogues contain 4’-cyano moiety and retain the 3’-hydroxyl moiety in the ribose moiety. CAdA and CdG were identified through the synthetic development of the congeners of 4’-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine (EFdA) that is a potent anti-HIV-1 drug currently undergoing phase 2b clinical trials in the US and other countries (Nakata et al., 2007; Michailidis et al., 2014; Salie et al., 2016). Because multiple antiviral mechanisms of RT inhibition by EFdA seem to be unique presumably for the 4’-modifed NRTIs (Michailidis et al., 2009; Maeda et al., 2014), we hypothesized that CdFA also retains some or all of these mechanisms to exert its anti-HBV activity, which should be different from the NRTIs currently approved for HBV treatment. Indeed, the present and previously published data of ours (Takamatsu et al., 2015) show that the 4’-modified NRTIs active against HBVWT are also active against HBVETVR and HBVADVR.

One significant disadvantage of some 4’-modified NRTIs including CAdA and CdG is their cytotoxicity (Kohgo et al., 2004; Takamatsu et al., 2015). In the present study we showed that CdA also turned out to be significantly cytotoxic; while CdFA was found to be much less toxic than CdA (Table 1). We do not know the mechanistic basis for the reduced toxicity of CdFA at this time; however, it is noteworthy that EFdA was generated by adding a fluorine atom at the 2-position in the purine moiety of 4’-ethynyl-2’-deoxy-adenosine (EdA) that was highly potent against HIV but overly cytotoxic (Maag et al., 1992; Kohgo et al., 1999). The addition of a fluorine atom at the 2-posision of 2’-deoxyadenosine converted EdA to virtually non-toxic compound with extremely potent activity against wild-type and various drug-resistant HIV-1 strains (Nakata et al., 2007). In fact, EFdA showed little inhibition of the activity of human DNA polymerases, α, β, and γ (Nakata et al., 2007). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that the reduced toxicity of CdFA was due to the introduction of a fluorine atom at the 7-position of adenine of CdA. Although fluorine substitution at the 2- or 3-position of a sugar is known to increase the chemical and metabolic stability of nucleoside analogues (Lee et al., 2002), the impact of fluorine substitution at the 7-position of a purine moiety is less understood at this time.

The present structural analyses, derived from sequence homology-based molecular models, revealed that the base of ETV-TP is projected to form a hydrogen bond with Met171, while CdFA-TP has all these polar interactions with RTWT except for Met171 (Fig. 5–a, b). Although ETV-TP has good Connolly surface interactions with Met204 and Asp205 (Fig. 5–c), CdFA-TP has good Connolly surface only contacts with Asp205 (Fig. 5–d). This difference in non-polar interactions along with Met171 may be partly responsible for the relatively greater anti-HBV potency against HBVWT of ETV-TP over CdFA-TP. It was also found that the projected polar interactions of both ETV-TP and CdFA-TP with HBV-RTETV-R are similar to those observed for HBV-RTWT. The most striking difference in nonpolar interactions arises from the interactions of residue 180 with the two inhibitors. The 4′-cyano group of CdFA-TP makes effective contacts with both Leu180 of RTWT and Met180 of RTETV-R (Fig. 5–d, and -h). However, the lack of the 4′-cyano in ETV-TP results in a drastic loss of interactions with Met180 of RTETV-R compared with Leu180 of RTWT (Fig. 5–c, and -g). The difference in these interactions with residue 180 probably results in CdFA-TP having a less drastic loss of anti-HBV potency (2.4-fold) compared to a more profound loss of potency (>250-fold) for ETV-TP for RTETV-R (Fig. 3; Table 2). It should be noted that the crystal structure of HBV-RT has not been solved due to the intractability of producing soluble recombinant HBV-RT. Thus, we have generated HBV-RT-mimicking HIV-1 RT species by incorporating one or more key HBV-RT’s active site amino acids into HIV-1 RT and have solved such “chimeric” HIV-1 RT/DNA/NRTI structures as surrogates (Yasutake et al., 2019). It is hoped that such studies help shed light on our understanding of interactions of anti-HBV therapeutic ligand and HBV-RT.

Nucleoside analogs with the 7-deaza-7-fluoro configuration might be of clinical utility, particularly because CdFA with such configuration much more than ADV and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (Table 1), and also more highly active against HBVADVR and HBVETVR than ADV and ETV, respectively (Fig. 3 and Table 2). The clinical practice guidelines for chronic hepatitis B virus infection (cHBV) treatment recommend using the most potent NRTIs with optimal resistance profiles (European Association for the Study of the Liver, 2017). ETV has high genetic barrier to resistance in treatment naïve patients (Tenney DJ et al., 2009), but not patients harboring LAM-resistant HBV (HBVLAMR) (Locarnini and Mason, 2006). Therefore, cHBV patients harboring HBVLAMR are recommended to receive TDF or ADV. However, TDF and ADV are known to cause severe long-term complications (Tanji et al., 2001; Parsonage MJ et al., 2005; Hoofnagle et al., 2007; Fontana, 2009). Because the IC50 value of CdFA is much lower than that of ADV and TDF in vitro (Table 1), lower dosage of CdFA would presumably suppress HBV viremia in cHBV patients, reducing the likelihood to cause severe complications. Recently, tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), a phosphonate prodrug of TDV, has been approved for the treatment of chronic HBV infection. Due to TAF suppresses HBV viremia with lower dosage (25 mg/day) than TDF, improving the bone and renal safety. Although the CC50 value of CdFA is much lower than that of TAF (Table 1), CdFA should be more closely compared to TAF to evaluate its clinical impact.

In conclusion, we identified novel 7-deaza-7-fluoro-nucleoside analog, CdFA, targeting HBV-RT against HBVWT, HBVETVR and HBVADVR. It is noteworthy that CdFA serves as a unique lead compound in further optimizing to strengthen activity to block HBV’s RT activity and to mitigate cytotoxicity to obtain more promising agents for cHBV treatment.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We designed, synthesized and identified a novel 4’-modified nucleoside, 4’-C-cyano-7-deaza-7-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine (CdFA).

CdFA strongly suppresses the production of wild-type and drug-resistant HBVs without significant cytotoxicity.

Molecular modeling suggested that the 4’-cyano of CdFA-TP forms good nonpolar contacts with RTWT’s Leu180 and RTETVR’s Met180.

CdFA serves as a unique lead compound in further optimizing drug development for infection with drug-resistant HBV variants.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

The present work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (R01AI121315 for HM); a grant for Development of Novel Drugs for Treating HBV infection and HIV-1 Infection/AIDS from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED)(JP19fk0310113 and JP18fk041001, respectively, for HM, JP19fk0310113 for YT); grants from Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences; and a grant from National Center for Global Health and Medicine Research Institute (HM). This study utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (https://hpc.nih.gov).

Conflict of interest

YT receives research support from FUJIFILM Corporation and Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University, and honoraria from Fujirebio Inc. and Gilead Sciences Inc.

List of Abbreviations

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- CdFA

4’-C-cyano-7-deaza-7-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine

- HBVWT

wild-type HBV

- ETV

entecavir

- HBVETVR

ETV-resistant HBV carrying L180M/S202G/M204V substitutions

- ADV

adefovir dipivoxil

- HBVADVR

ADV-resistant HBV carrying A181T/N236T substitutions

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- RTWT

HBVwt reverse transcriptase

- NRTIs

nucleoside/nucleotide RT inhibitors

- TDF

tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

- TAF

tenofovir alafenamide

- CdG

4’-C-cyano-2’-deoxyguanosine

- CAdA

4’-C-cyano-2-amino-2’-deoxyadenosine

- CdA

4’-C-cyano-2’-deoxyadenosine

- S.I.

selectivity index

- MTT

methyl-thiazol tetrazolium

- HBVWTCe

wild type HBV genotype Ce

- ssDNA

single-stranded DNA

- h-albumin

Serum human albumin

- EFdA

4’-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine

- EdA

4’-ethynyl-2’-deoxyadenosine

- cHBV

chronic hepatitis B virus infection

- HBVL180M/M204V

LAM-resistant mutations such as M204V and L180M

- HBVWTD

wild type HBV genotype D

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- TCID50

50% tissue culture infectious dose

- IC50

50% inhibitory concentration

- CC50

50% cytotoxicity concentration

- SEAP

secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase

- DIG

digoxigenin

- uPA

urokinase-type plasminogen activator

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficiency

- pt

primer-templates

- TP

triphosphate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- World Health Organization, 2017. Global Hepatitis Report, 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255016.

- Menéndez-Arias L, Álvarez M, Pacheco B, 2014. Nucleoside/nucleotide analog inhibitors of hepatitis B virus polymerase: mechanism of action and resistance. Curr Opin Virol. 8, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HL., Fung S, Seto WK., Chuang WL., Chen CY, Kim HJ, Hui AJ, Janssen HL, Chowdhury A, Tsang TY, Mehta R, Gane E, Flaherty JF, Massetto B, Gaggar A, Kitrinos KM, Lin L, Subramanian GM, McHutchison JG, Lim YS, Acharya SK, Agarwal K; GS-US-320–0110 Investigators., 2016. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the treatment of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 1, 185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orito E, Mizokami M, Ina Y, Moriyama EN., Kameshima N, Yamamoto M, Gojobori T, 1989. Host-independent evolution and a genetic classification of the hepadnavirus family based on nucleotide sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 7059–7062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak MA., Bonhoeffer S, Hill AM, Boehme R, Thomas HC, McDade H, 1996. Viral dynamics in hepatitis B virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93, 4398–4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamatsu Y, Tanaka Y, Kohgo S, Murakami S, Singh K, Das D, Venzon DJ, Amano M, Higashi-Kuwata N, Aoki M, Delino NS, Hayashi S, Takahashi S, Sukenaga Y, Haraguchi K, Sarafianos SG, Maeda K, Mitsuya H, 2015. 4’-modified nucleoside analogs: potent inhibitors active against entecavir-resistant hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 62, 1024–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi-Kuwata N, Hayashi S, Das D, Kohgo S, Murakami S, Hattori S, Imoto S, Venzon D, Singh K, Sarafianos S, Tanaka Y, Mitsuya H, 2019. CMCdG, a novel nucleoside analog with favorable safety features, exerts potent activity against wild-type and entecavir-resistant hepatitis B virus. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 63, e02143–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Murakami S, Omagari K, Matsui T, Iio E, Isogawa M, Watanabe T, Karino Y, Tanaka Y, 2015Characterization of novel entecavir resistance mutations. J Hepatol. 63, 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohgo S, Yamada K, Kitano K, Iwai Y, Sakata S, Ashida N, Hayakawa H, Nameki D, Kodama E, Matsuoka M, Mitsuya H, Ohrui H, 2004. Design, efficient synthesis, and anti-HIV activity of 4’-C-cyano- and 4’-C-ethynyl-2’-deoxy purine nucleosides. Nucleosides, nucleotides & nucleic acids. 23, 671–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama EI.,Kohgo S, Kitano K, Machida H, Gatanaga H, Shigeta S, Matsuoka M, Ohrui H, Mitsuya H, 2001. 4’-Ethynyl nucleoside analogs: potent inhibitors of multidrug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus variants in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 45, 1539–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki M, Chang SB, Das D, Martyr C, Delino NS, Takamatsu Y, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H, 2019. A novel HIV-1 protease inhibitor, GRL-044, has potent activity against various HIV-1s with an extremely high genetic barrier to the emergence of HIV-1 drug resistance. Global Health & Medicine. 1, 36–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe A, Inoue K, Tanaka T, Kato J, Kajiyama N, Kawaguchi R, Tanaka S, Yoshiba M, Kohara M,1999. Quantitation of hepatitis B virus genomic DNA by real-time detection PCR. Journal of clinical microbiology. 37, 2899–2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata H, Amano M, Koh Y, Kodama E, Yang G, Bailey CM, Kohgo S, Hayakawa H, Matsuoka M, Anderson KS, Cheng YC, Mitsuya H, 2007Activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1, intracellular metabolism, and effects on human DNA polymerases of 4’-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine.Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 51, 2701–2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michailidis E, Huber AD, Ryan EM, Ong YT, Leslie MD, Matzek KB, Singh K, Marchand B, Hagedorn AN, Kirby KA, Rohan LC, Kodama EN, Mitsuya H, Parniak MA, Sarafianos SG, 2014. 4’-Ethynyl-2-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine (EFdA) inhibits HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with multiple mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 289, 24533–24548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salie ZL., Kirby KA, Michailidis E, Marchand B, Singh K, Rohan LC, Kodama EN, Mitsuya H, Parniak MA, Sarafianos SG, 2016. Structural basis of HIV inhibition by translocation-defective RT inhibitor 4’-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine (EFdA). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113, 9274–9279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michailidis E, Marchand B, Kodama EN, Singh K, Matsuoka M, Kirby KA, Ryan EM, Sawani AM, Nagy E, Ashida N, Mitsuya H, Parniak MA, Sarafianos SG, 2009Mechanism of inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by 4’-Ethynyl-2-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine triphosphate, a translocation-defective reverse transcriptase inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 284, 35681–35691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Desai DV, Aoki M, Nakata H, Kodama EN, Mitsuya H, 2014. Delayed emergence of HIV-1 variants resistant to 4’-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine: comparative sequential passage study with lamivudine, tenofovir, emtricitabine and BMS-986001. Antivir Ther. 19, 179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maag H, Rydzewski RM, McRoberts MJ, Crawford-Ruth D, Verheyden JP, Prisbe EJ, 1992. Synthesis and anti-HIV activity of 4’-azido- and 4’-methoxynucleosides. J Med Chem. 35, 1440–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohgo S, Kodama E, Shigeta S, Saneyoshi M, Machida H, Ohrui H, 1999Synthesis of 4’-substituted nucleosides and their biological evaluation. Nucleic acids symposium series. 127–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Choi Y, Gumina G, Zhou W, Schinazi RF., Chu CK, 2002. Structure-activity relationships of 2’-fluoro-2’,3’-unsaturated D-nucleosides as anti-HIV-1 agents. J Med Chem. 45, 1313–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasutake Y, Hattori SI., Tamura N, Matsuda K, Kohgo S, Maeda K, Mitsuya H, 2019. Active-site deformation in the structure of HIV-1 RT with HBV-associated septuple amino acid substitutions rationalizes the differential susceptibility of HIV-1 and HBV against 4’-modified nucleoside RT inhibitors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 509, 943–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver., 2017. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 67, 370–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenney DJ., Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Pokornowski KA, Eggers BJ, Fang J, Wichroski MJ, Xu D, Yang J, Wilber RB, Colonno RJ, 2009. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naive patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 49, 1503–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locarnini S, Mason WS, 2006. Cellular and virological mechanisms of HBV drug resistance. J Hepatol. 44, 422–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanji N, Tanji K, Kambham N, Markowitz GS, Bell A, D’Agati VD., 2001. Adefovir nephrotoxicity: possible role of mitochondrial DNA depletion. Hum Pathol. 32, 734–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsonage MJ., Wilkins EG, Snowden N, Issa BG, Savage MH, 2005. The development of hypophosphataemic osteomalacia with myopathy in two patients with HIV infection receiving tenofovir therapy. HIV Med. 6, 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoofnagle JH, Doo E, Liang TJ, Fleischer R, Lok AS, 2007. Management of hepatitis B: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology. 45, 1056–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana RJ, 2009. Side effects of long-term oral antiviral therapy for hepatitis B. Hepatology. 49, S185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.