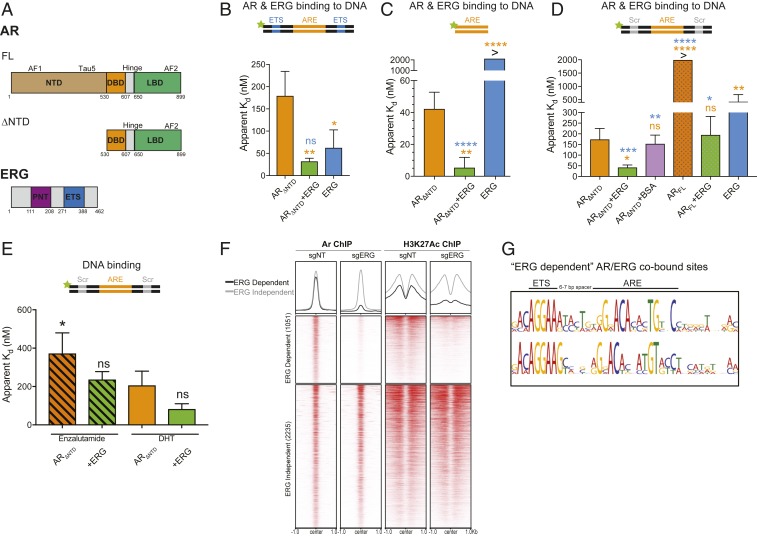

Fig. 1.

ERG directly stimulates AR independent of its DNA binding activity. (A) Domain structures of AR (FL and ∆NTD) and ERG. (B–E) AR binding to various 5′ fluorescein-labeled ARE dsDNA in the presence or absence of ERG was evaluated by fluorescence polarization. Data shown as mean ± SD (n = 3 technical replicates; one-way ANOVA, with orange and blue asterisks comparing to either AR and ERG, respectively). (B) ARΔNTD binding to ARE dsDNA containing an ETS consensus site. (C) ARΔNTD DNA binding on a minimal ARE sequence. (D) ARΔNTD and ARFL binding to ARE dsDNA bearing a scrambled (Scr) ETS site. (E) ARE/Scr DNA binding of antagonist (enzalutamide)- and agonist (DHT)-bound ARΔNTD. (F) ChIP-seq profile and heatmap derived from previously published Pten−/−;Rosa26-ERG mouse prostate organoids with ERG intact (sgNT) or depleted by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockdown (sgERG) (19). AR/ERG cobound peaks are separated into ERG dependent (AR binding is diminished by ERG knockout) and ERG independent (AR binding unchanged). (G) Top motif spacing of ERG/AR codependent peaks using SPAMO shows a 6- to 7-bp insertion is consistently observed between an ETS consensus motif and AREs. ****P ≤ 0.0001; ***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤0.01; *P ≤ 0.05; ns, not significant, P > 0.05.