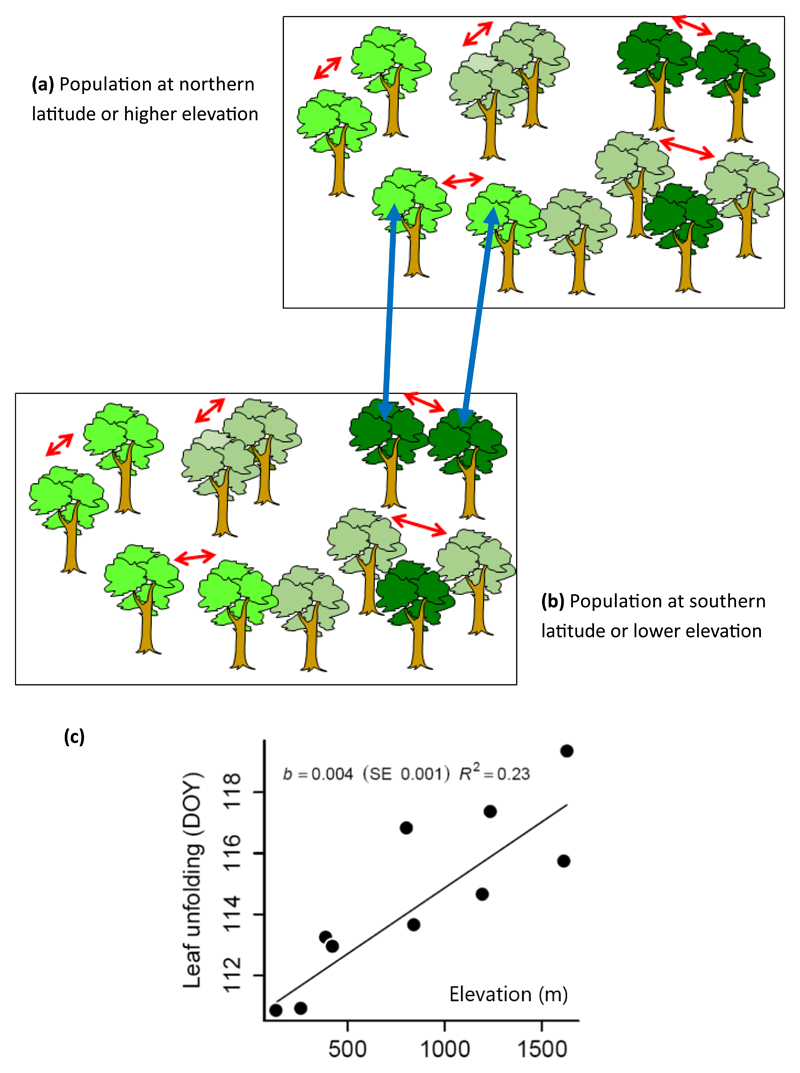

As bud phenology is correlated to the growth rhythm and to flowering in oaks, it

is intensively studied in microevolution. The discovery of very large within and

between population genetic variation has raised numerous questions about the

mechanisms maintaining its evolutionary potential and its contribution to local

adaptation. In addition to common evolutionary drivers as gene flow, and

selection, assortative mating has a significant contribution to phenological

responses of oak populations. This figure illustrates how gene flow and

assortative mating shape clinal genetic variation between populations of higher

latitude/elevation (a) and lower latitude/elevation (b).

-

a)

and b) Within natural populations early flushing trees tend to mate

with early flushing trees, resulting in positive assortative mating.

Trees with similar phenotypes regarding date of bud burst

preferentially mate within populations. Positive assortative mating

is shown by red arrows between trees sharing similar colours on

graph a) (colours indicate here the timing of bud burst). However

matings resulting from immigrant pollen flow are likely to result in

negative assortative mating especially if source populations are

farther away in latitude or elevation. Populations at northern

latitudes or higher altitude flush on average later than populations

from more southern latitudes or from lower elevations because of

temperature differences. Hence successful matings resulting from

pollen flow can only associate late flushing trees from the south

(or low elevation) to early flushing trees in the north (or at

higher elevation) (negative assortative mating shown by blue arrows

on b). As a result, assortative mating and gene flow contribute to a

directional filtering of late flushing genes to the northern (or

higher elevation) populations (

Soularue & Kremer, 2012;

Soularue & Kremer, 2014).

-

c)

Within population positive assortative mating generates higher within

population genetic variance, whereas negative assortative mating and

gene flow creates genetic clines along temperature gradients in the

landscape, as shown here by the genetic divergence of the time of

bud burst along an elevational gradient in sessile oak in the

Pyrénées (

Firmat

et al., 2017)