Abstract

Humans generally prefer gait patterns with a low metabolic cost, but it is unclear how such patterns are chosen. We have previously proposed that humans may use proprioceptive feedback to identify economical movement patterns. The purpose of the present experiments was to investigate the role of plantarflexor proprioception in the adaptation toward an economical gait pattern. To disrupt proprioception in some trials, we applied noisy vibration (randomly varying between 40–120 Hz) over the bilateral Achilles tendons while participants stood quietly or walked on a treadmill. For all 10 min walking trials, the treadmill surface was initially level before slowly increasing to a 2.5% incline midway through the trial without participant knowledge. During standing posture, noisy vibration increased sway, indicating decreased proprioception accuracy. While walking on a level surface, vibration did not significantly influence stride period or metabolic rate. However, vibration had clear effects for the first 2–3 min after the incline increase; vibration caused participants to walk with shorter stride periods, reduced medial gastrocnemius (MG) activity during mid-stance (30–65% stance), and increased MG activity during late-stance (65–100% stance). Over time, these metrics gradually converged toward the gait pattern without vibration. Likely as a result of this delayed adaptation to the new mechanical context, the metabolic rate when walking uphill was significantly higher in the presence of noisy vibration. These results may be explained by the disruption of proprioception preventing rapid identification of muscle activation patterns which allow the muscles to operate under favorable mechanical conditions with low metabolic demand.

Keywords: Gait adaptation, Metabolic cost, Muscle activity, Tendon vibration

1. Introduction

Minimization of metabolic energy expenditure is often cited as a primary goal of human walking (Alexander, 2002), but the mechanisms used to identify economical movement patterns are unclear. Prescribing non-preferred step lengths or widths causes an increase in metabolic rate (Donelan et al., 2001; Minetti et al., 1995; Umberger and Martin, 2007; Zarrugh and Radcliffe, 1978), indicating a preference for economical gait patterns. When humans self-select their gait characteristics, the preferred gait pattern is influenced by the mechanical context, such as gait speed or surface incline (Leroux et al., 2002; Minetti et al., 1995). However, the new preferred gait pattern does not arise immediately after a change in mechanical context. Instead, humans gradually adapt their gait pattern over tens of seconds, possibly driven by direct minimization of metabolic expenditure (O′Connor and Donelan, 2012; Pagliaraetal.,2014; Snaterse etal.,2011).

We recently proposed that adaptation toward an economical movement pattern may also involve proprioception (Dean, 2013). Proprioceptive feedback can provide information about muscle contraction characteristics (e.g. muscle velocity and force) which are closely linked to metabolic demand (Griffin et al., 2003; Ryschon et al., 1997). Integrating this mechanical information into an estimate of metabolic cost may allow faster identification of an economical movement pattern, as the time course of proprioceptive feedback is substantially faster than the known pathways for direct metabolic feedback (Ainslie and Duffin, 2009; Kaufman and Hayes, 2002; Starr et al., 1981).

During walking, proprioception may help humans effectively take advantage of body mechanics to produce economical propulsion. The plantarflexors, important contributors to gait propulsion, remain near-isometric for much of the stance phase while the Achilles tendon stores mechanical energy (Cronin et al., 2010; Farris and Sawicki, 2012; Ishikawa et al., 2005; Lichtwark and Wilson, 2006). The subsequent return of this stored energy allows strong push-off forces without requiring metabolically costly high-velocity muscle contractions (Farris and Sawicki, 2012; Lichtwark and Wilson, 2006). This musculotendon behavior persists when walking on moderate inclines or declines, despite large changes in plantarflexor activation (Lichtwark and Wilson, 2006). Humans could conceivably generate this behavior by monitoring muscle spindle feedback and adjusting plantarflexor activation to hold the muscle near-isometric.

The roles of proprioceptive feedback during functional tasks can be investigated using tendon vibration. Muscle spindles are particularly sensitive to vibration, which the nervous system interprets as muscle lengthening (Goodwin et al., 1972; Roll and Vedel, 1982). The onset of Achilles tendon vibration during standing posture causes posterior sway, a response to the illusion of anterior sway induced by increased plantarflexor spindle feedback (Eklund et al.,1972; Ivanenko et al., 2000; Kavounoudias et al., 1999). During walking, the effects of continuous Achilles tendon vibration are less apparent (Courtine et al., 2001; Ivanenko et al., 2000; Verschueren et al., 2002), possibly because humans ignore the constant vibratory background signal while monitoring the superimposed natural sensory signal (Courtine et al., 2001). Applying noisy, unpredictable vibration may more effectively reduce the accuracy of available proprioceptive feedback.

The purpose of this experiment was to test whether adaptation toward an economical gait pattern is influenced by disruption of plantarflexor proprioceptive feedback. We disrupted proprioception by applying noisy vibration over the Achilles tendons, and quantified walking behavior in response to a small change in surface incline. We hypothesized that noisy vibration would delay or reduce the adaptation to the new mechanical context, increasing metabolic expenditure.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Ten young, healthy individuals (8 female, 2 male; age=2472 yr; mass=64±9 kg; height=1.68±0.07 m; mean±s.d.) participated in this experiment. All participants provided informed consent, using forms and protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina and consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Vibration characteristics

During some trials, noisy vibration was applied to the bilateral Achilles tendons using small, eccentrically weighted motors (35 g; 35 mm × 20 mm × 18 mm outer dimensions) strapped approximately 4 cm above the ankle joint (Floyd et al., 2014). The vibration characteristics varied randomly over time, between 40 Hz vibration (0.18 mm amplitude) and 120 Hz vibration (0.31 mm amplitude). Previously, the low end of this frequency range had no effect on an ankle movement matching task, with the effect of vibration increasing with higher frequencies across this range (Floyd et al., 2014). Therefore, the effects of the applied vibration varied over time, and were not predictable.

2.3. Standing posture trials

Participants completed three 90 s trials in which they stood on a force plate (Bertec; Columbus, OH) with their eyes closed, arms crossed, and feet positioned parallel and as close together as possible without touching. Noisy vibration was off for the first 30 s, turned on for the next 30 s, and turned off for the final 30 s. Trials were separated by 2 min of rest.

Ground reaction force and moment data were collected from the force plate at 1000 Hz, and low-pass filtered at 3 Hz. While previous studies have investigated whether constant frequency vibration influences average standing posture (Eklund et al., 1972; Ivanenko et al., 2000; Kavounoudias et al., 1999), our focus was on whether noisy vibration increased postural sway by reducing the accuracy of available proprioceptive feedback. Therefore, we calculated anteroposterior CoP speed, a measure of postural sway (Jeka et al., 2004), as the absolute value of the time derivative of anteroposterior CoP position. For each participant, the average CoP speed was calculated across all three trials for the 30 s periods before vibration, during vibration, and after vibration.

2.4. Walking trials

Participants performed a series of treadmill (Bertec; Columbus, OH) walking trials at 1.25 m/s. Participants wore a harness attached to an overhead rail which did not support body weight, but would have prevented a fall in case of a loss of balance. Participants first performed a 10 min trial in order to become accustomed to treadmill walking (Zeni and Higginson, 2010). Participants then completed four 10 min trials in which the treadmill incline slowly (over 7 s) increased to 2.5% at the 5 min mark. Incline changes were not visually apparent to participants, as they were instructed to keep their vision focused forward, the metabolic cart mask (see below) obstructed their vision of the treadmill belt, and this treadmill provides users with no visual feedback of their performance (e.g. speed, incline). After completion of the 10 min walking trial, the treadmill was returned to level before the treadmill belt was stopped. All walking trials were separated by 5 min of rest.

While the vibration device was worn for all trials, noisy vibration was continuously applied to the bilateral Achilles tendons in only two of the walking trials. To account for any effects of trial order, vibration was applied in the first and third trials for 5 participants, and in the second and fourth trials for the other 5 participants. Participants were assigned to these groups in alternating order. To determine whether participants were consciously aware of changes in treadmill incline, they were asked a series of questions in random order after the experiment (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant responses to questions asked at completion of the walking trials. The question regarding treadmill slope was of primary interest. All other questions were distractors.

| Did you notice | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| The motor on your left ankle vibrating in any trials? | 10 | 0 |

| The motor on your right ankle vibrating in any trials? | 10 | 0 |

| Changes in the speed of the treadmill in any trials? | 1 | 9 |

| Changes in the slope of the treadmill in any trials? | 0 | 10 |

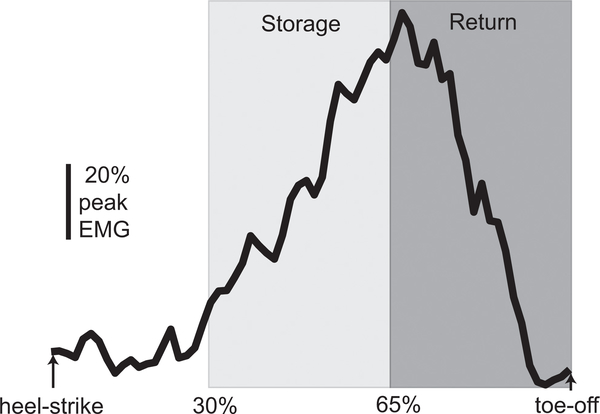

The locations of active LED markers (Phase Space; San Leandro, CA) placed on the left and right heels were sampled at 120 Hz, with their calculated anteroposterior velocities used to identify heel-strike and toe-off events (Zeni et al., 2008). Stride period was calculated as the time between consecutive right heel-strike events. Breath-by-breath oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production were measured using a metabolic cart (Cosmed; Rome, Italy), and metabolic rate was calculated using a standard equation (Brockway, 1987). Metabolic rate was normalized by body mass, and the metabolic rate during a 6 min quiet standing trial was subtracted. Surface electromyographic (EMG) electrodes (Motion Lab Systems; Baton Rouge, LA) over the bilateral medial gastrocnemius (MG) muscles were sampled at 1000 Hz. Our focus on the MG was based on our previous finding that this muscle exhibits clear adaptation in its activity following changes in surface incline, unlike the soleus (Wellinghoff et al., 2014). EMG data were band-pass filtered (20–500 Hz), rectified, low-pass filtered (50 Hz), and divided into strides based on heel-strike timing. For each muscle, EMG data were normalized by the peak EMG value of an average stride while walking on level ground. Within each stance phase, MG EMG traces were divided into storage and return phases (Fig. 1) (Wellinghoff et al., 2014). The selection of the storage phase (30–65% of stance) was conservatively chosen to include only a time range in which the Achilles tendon lengthens, storing mechanical energy (Cronin et al., 2010; Farris and Sawicki, 2012; Ishikawa et al., 2005; Lichtwark and Wilson, 2006). The defined return phase (65–100% of stance) includes the period in which the Achilles tendon recoils, returning mechanical energy. For each stride, the average level of MG activity was calculated during the storage and return phases.

Fig. 1.

Typical average trace of MG muscle activity pattern during the stance phase, from heel-strike to toe-off. The mean EMG level was calculated during a storage phase (30–65% of stance) and a return phase (65–100% of stance).

For each participant, we calculated the mean stride period and muscle activity values within 5 s bins, with bin assignment defined by when a stride began. We averaged data from the two trials with noisy vibration and data from the two trials without vibration, reducing variability not attributable to vibration condition. This approach resulted in one data point per participant for each of the 60 bins during the initial 5 min period of level walking. For uphill walking, we did not analyze data during the 7 s change in incline, resulting in 58 bins. Due to high variability in breath-bybreath metabolic gas values, we combined metabolic rate data into 10 30 s bins at each incline. Again, we ignored the period in which incline was changing, so the first bin when walking uphill contained 23 s. Data were again averaged for the two trials with and without vibration. For plotting purposes, we normalized each of the gait metrics described above by its mean value for that individual across all walking trials, and converted these normalized values back into the more familiar units by multiplying by the average value of this metric across individuals. This allows the figures to more clearly illustrate the effects of vibration, which may otherwise be obscured due to large variations in gait characteristics across individuals.

2.5. Statistics

For standing posture trials, we used a repeated measures one-way ANOVA to identify significant effects of time period (before vibration, during vibration, after vibration) on average CoP speed.

In the case of a significant main effect (p <0.05), we performed post-hoc paired t-tests to make comparisons between each time period. To account for multiple comparisons, the required alpha value of these post-hoc tests was adjusted using a Bonferroni correction (to 0.017).

For walking trials, we tested the effects of vibration and time on stride period, metabolic rate, and MG activity. As the effects of incline on these metrics are well known (Leroux et al., 2002; Lichtwark and Wilson, 2006; Margaria, 1968) and our primary interest was on the adaptation following a change in mechanical context, we performed separate analyzes at each incline level. For each metric, we performed a repeated measures two-way ANOVA with interactions using vibration condition (2 levels; control vs. vibration) and time period (5 levels; each 1 min period of walking) as independent variables. A significant interaction between vibration condition and time period (p <0.05) was interpreted as vibration influencing the changes in gait performance over time (i.e. adaptation). In this case, we performed subsequent post-hoc paired t-tests in which we tested whether vibration had a significant effect during each minute-long period of walking. The required alpha value of these post-hoc tests was adjusted using a Bonferroni correction (to 0.01).

3. Results

3.1. Standing posture

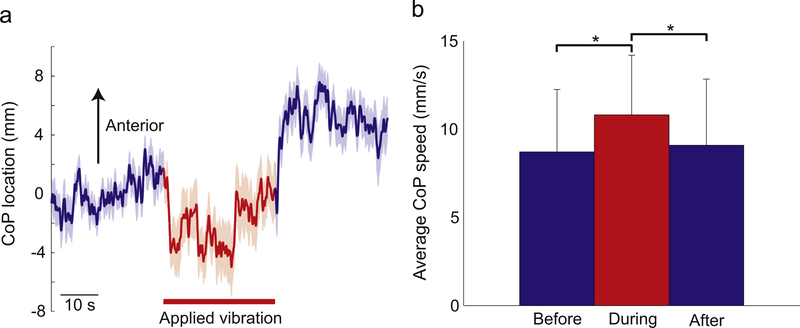

Noisy vibration had clear effects on standing posture, as participants swayed posteriorly when vibration was applied and anteriorly when vibration was terminated (Fig. 2a). Vibration also increased ongoing sway, as average CoP speed was highest while vibration was applied (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Effects of Achilles tendon vibration on posture. (a) The group average CoP trace illustrates the vibration-driven shifts in CoP location over time. To account for the initial location on the force plate, all changes in CoP position over time are illustrated relative to the average position during the first 30 s of standing. The shaded area indicates standard error. (b) Time period significantly (p=0.0004) influenced average anteroposterior CoP speed, which was highest during vibration. Error bars indicate standard deviation and asterisks (*) indicate a significant difference between the indicated time periods (post-hoc tests; p <0.017).

3.2. Perception of treadmill incline

Participants were not consciously aware of the small changes in treadmill incline while walking. Following completion of the experiment, no participant reported noticing an incline change (Table 1).

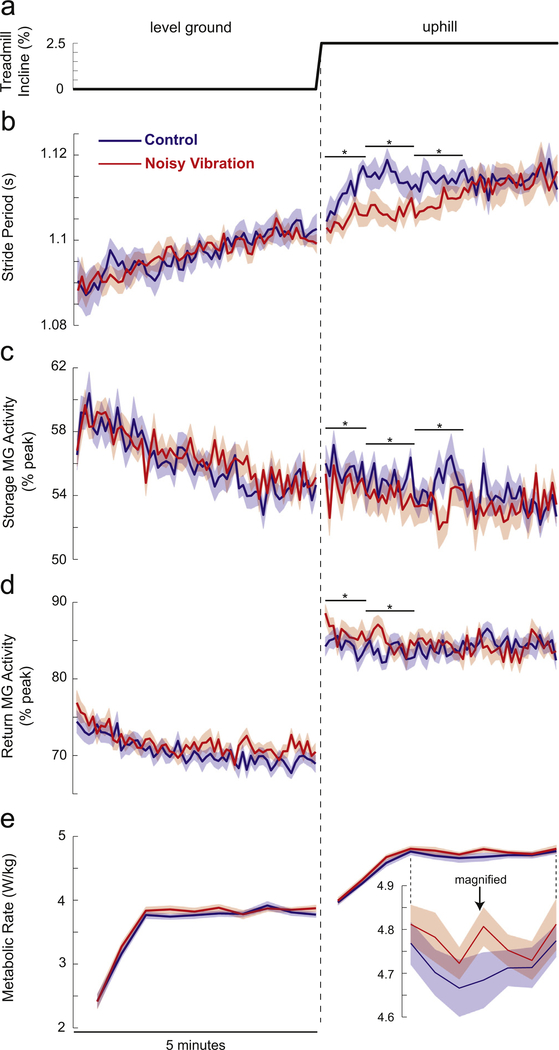

3.3. Level surface walking

While walking on a level surface, noisy vibration did not influence the observed gait adaptation (statistics presented in Table 2). Stride period gradually increased over time, independent of the presence of vibration (Fig. 3b). MG activity was slightly higher during trials with vibration than control trials (by an average of 0.7% in the storage phase and 1.6% in the return phase), but underwent similar gradual decreases over time with or without vibration (Fig. 3c and d). Metabolic rate rapidly increased over the first few minutes of walking before reaching a plateau (Fig. 3e). Vibration did not affect the average metabolic rate or its change over time, either for the entire 5 min walking period or when analysis was restricted to the final 3 min in which metabolic rate reached a plateau.

Table 2.

Summarized results of the statistical tests for walking trials. Bold text indicates a significant (p<0.05) effect. Vibration had more extensive effects on gait performance when walking uphill. The significant interactions between time and vibration during uphill walking indicate that vibration influenced the changes in gait performance over time (adaptation). More detailed interpretation of these results is found in the main text.

| Level ground walking |

Uphill walking |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time p | Vibration p | Interaction p | Time p | Vibration p | Interaction p | |

| Stride period | <0.0001 | 0.82 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Storage MG activity | <0.0001 | 0.007 | 0.09 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.013 |

| Return MG activity | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.26 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.0001 |

| Metabolic rate | <0.0001 | 0.18 | 0.88 | <0.0001 | 0.015 | 0.94 |

| Metabolic rate (last 3 min) | 0.77 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.47 | 0.024 | 0.67 |

Fig. 3.

Effects of Achilles tendon vibration on gait adaptation. (a) Treadmill incline changed from 0% to 2.5% midway through the 10 min trial. For all panels, the column to the left of the dashed line illustrates behavior while walking on level ground, and the right column illustrates behavior while walking uphill. (b) Noisy vibration had minimal effects on stride period while walking on level ground, but slowed the gradual increase in stride period after the incline transition. (c) While walking on level ground, vibration slightly increased storage phase MG activity. In contrast, vibration caused reductions in storage phase MG activity during the first few minutes of walking after the incline transition. (d) Vibration increased return phase MG activity while walking on level ground, and for the first few minutes of walking uphill. (e) On level ground, vibration did not influence metabolic rate. After the incline transition, metabolic rate was significantly higher during trials in which vibration was applied. For clarity, this is magnified for the final 3 min of uphill walking. For panels (b)–(e), shaded areas indicate standard errors, while asterisks (*) indicate a significant effect of vibration (post-hoc tests; p <0.01) during the indicated time period.

3.4. Uphill walking

Unlike when walking on a level surface, noisy vibration had clear effects on gait adaptation following the increase in treadmill incline (statistics in Table 2). From the last minute of level walking to the last minute of uphill walking, stride period increased by an average of 13 ms, whether or not vibration was applied. However, this adaptation toward the longer, slower strides typically used when walking uphill was substantially slowed by vibration

(Fig. 3b). Under control conditions, average stride period first reached the final plateau level after 40 s of walking. In contrast, this stride period plateau was only reached after 180 s when vibration was applied.

Vibration also influenced MG activity and metabolic rate while walking uphill. The effects of vibration on MG activity were only present for the first few minutes after the incline transition before converging to the control condition. Storage phase MG activity was initially lower in the presence of noisy vibration compared to the control condition, by an average of 2.0% for the first 3 min of walking uphill (Fig. 3c). In contrast, return phase MG activity was initially higher during vibration trials than control trials, by an average of 1.8% over the first 2 min (Fig. 3d). As during level ground walking, metabolic rate increased over the first few minutes before reaching a plateau (Fig. 3e). Metabolic rate was higher during vibration trials than control trials, by an average of 1.2% over the entire 5 min period and by 1.3% over the final 3 min period in which metabolic rate plateaued.

4. Discussion

Noisy Achilles tendon vibration delayed gait adaptation after a change in mechanical context, providing direct evidence for the use of proprioceptive feedback in adaptation toward an economical movement pattern. While vibration had minimal effects during an initial period of level ground walking, stride period adaptation was slowed and metabolic rate was higher following an increase in treadmill incline, supporting our hypothesis.

Noisy vibration caused increased sway during standing posture, likely due to decreased accuracy of available afferent feedback. The vibration pattern was unpredictable, randomly changing frequencies in order to vary its effects on sensation (Floyd et al., 2014; Roll and Vedel, 1982). In contrast, most previous work has focused on the shift in body position caused by the onset of constant-frequency vibration (Eklund et al., 1972; Ivanenko et al., 2000; Kavounoudias et al., 1999). In addition to the posterior shift when vibration began, participants also shifted farther anteriorly than their initial position once vibration was terminated. Such after-effects have been noted previously, and attributed to sustained changes in perception evoked by vibration (Rogers et al., 1985; Wierzbicka et al., 1998). However, the observed increase in CoP speed did not exhibit after-effects, indicating that the intended effects of our noisy vibration were restricted to the vibration period.

Noisy vibration did not appear to influence the identification of an economical gait pattern while walking on level ground. Vibration caused a slight increase in MG activity, possibly from increased excitation through muscle spindle reflex pathways (Burke and Schiller, 1976). However, the higher muscle activity did not influence the gradual increase in stride period, and was not sufficient to cause a significant increase in metabolic rate. The gradual changes in stride period and MG activity during this period of putatively “steady-state” walking may be surprising, but have been reported previously (Wellinghoff et al., 2014). Speculatively, these slow changes may be attributable to increasing confidence during the treadmill walking task, as a more relaxed gait pattern can be accompanied by longer stride periods and decreased muscle activity (Hunter et al., 2010; Monsch et al., 2012). Whatever the cause of this initial adaptation, it is apparently not dependent on accurate plantarflexor proprioception. Perhaps these gradual changes in gait behavior at the start of a treadmill walking bout were sufficient to mask any underlying effects of vibration.

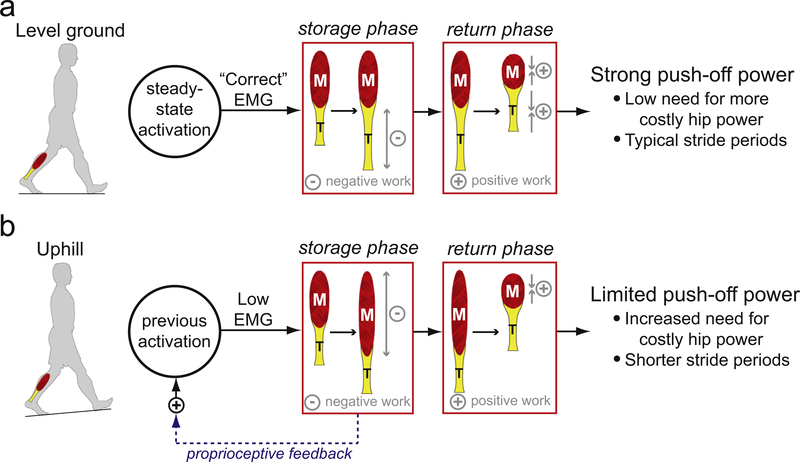

The effects of noisy vibration became apparent following a change in mechanical demand. Vibration slowed the gradual increase in stride period after the incline transition, as participants required three minutes to reach the same plateau which was reached within less than one minute without vibration. The higher metabolic rate observed for the vibration condition can likely be attributed to this delayed adaptation, as simply applying vibration did not increase metabolic rate during level walking. The combination of our stride period, MG activity, and metabolic rate results can potentially be explained by iterative adaptation of the preferred gait pattern based on proprioceptive feedback (Fig. 4). Prior to the incline transition, an appropriately chosen plantarflexor activation pattern would allow the Achilles tendon to effectively store and return mechanical energy while the muscle operates under favorable mechanical conditions, remaining near-isometric during the storage phase and shortening at a moderate velocity during the return phase (Fig. 4a) (Cronin et al., 2010; Farris and Sawicki, 2012; Ishikawa et al., 2005; Lichtwark and Wilson, 2006; Rubenson et al., 2012). Such mechanical behavior would allow strong, economical propulsion. Following a change in incline, plantarflexor activation must be adjusted in order to effectively store and return mechanical energy using the Achilles tendon (Lichtwark and Wilson, 2006). By sensing changes in MG velocity using muscle spindle feedback, humans could iteratively adjust their muscle activation patterns to match the new mechanical context, allowing appropriate increases in push-off power and producing the longer stride periods typical when walking uphill. Disrupting proprioception with noisy tendon vibration may prevent accurate sensation of MG velocity, thus slowing the identification of an appropriate level of storage phase activity to hold the muscle near-isometric (Fig. 4b). In turn, the muscle would experience less favorable contractile conditions during the return phase, requiring greater MG activity to produce similar levels of push-off power. Any reductions in push-off power would likely require more hip power and cause shorter than typical stride periods (Lewis and Ferris, 2008). While this proposed mechanism is consistent with the present results, it should be directly tested using ultrasound imaging to measure muscle fascicle mechanics during the adaptation process (Cronin and Lichtwark, 2013).

Fig. 4.

Schematic illustration of the proposed relationship between proprioceptive feedback and gait behavior. (a) During steady-state walking, a “correctly” chosen activation pattern will allow the muscle (M) to operate under favorable contractile conditions while the tendon (T) stores and returns mechanical energy, producing strong push-off power. (b) Following an incline transition, the previous plantarflexor activation pattern may no longer be appropriate. The resultant less favorable muscle contractile conditions and reduced tendon energy return would decrease push-off power. Proprioceptive feedback could contribute to the adjustment of plantarflexor activation, in order to return to mechanically advantageous musculotendon behavior.

The observed effects of vibration, while significant, were small and short-lasting. For example, the average increase in metabolic rate caused by noisy vibration was only 0.06 W/kg (1.2%). The effects of vibration were likely so small because the sensory perturbation itself was quite small. The average vibration-induced posterior sway was only ~2 mm, and participants never reported any perception of imbalance during either standing or walking. Additionally, the changes in mechanical demand (below perceptual threshold) were small, likely limiting the observable magnitude of the adaptation. An alternative approach of applying larger sensory perturbations or larger changes in mechanical demand may have increased the observed effects of vibration, but may have also caused the use of a more conservative gait pattern (Monsch et al., 2012) or large jumps in behavior based on pre-programmed motor plans rather than gradual adaptation (O′Connor and Donelan, 2012; Pagliara et al., 2014; Snaterse et al., 2011). Finally, noisy vibration slowed but did not prevent stride period adaptation when walking uphill. The lengthened time course may be the result of basing adaptation on slower sources of metabolic feedback instead the disrupted fast proprioceptive feedback.

Given the negative effects of disrupting proprioceptive feedback, a logical next question is whether gait adaptation can be improved in either healthy controls or clinical populations by enhancing proprioception. Among healthy controls, proprioceptive sensitivity can be increased through white noise tendon vibration at amplitudes below the threshold for conscious detection (Ribot-Ciscar et al., 2013), likely due to the phenomenon of stochastic resonance (Chow et al., 1998). Using such methods to enhance proprioception could have even greater value for clinical populations with impaired proprioception due to peripheral neuropathies (van Deursen and Simoneau, 1999) or stroke (Connell et al., 2008). The present work suggests that enhanced proprioception could allow increased gait economy in addition to the commonly cited effects on balance (Stephen et al., 2012; Tyson et al., 2013).

In conclusion, the present experiments provide direct evidence that proprioceptive feedback contributes to adaptation toward an economical gait pattern. The observed gait adaptation after a change in mechanical demand may be due to adjustment of muscle activation patterns to allow the muscle to operate under favorable mechanical conditions, although this should be directly tested using ultrasound. The relationship between proprioception and metabolic cost suggests that enhancing proprioceptive feedback in clinical populations could have the potential to improve gait economy and increase functional mobility.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a Career Development Award (1 IK2 RX000750) from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service. Study sponsors had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Ainslie PN, Duffin J, 2009. Integration of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and chemoreflex control of breathing: mechanisms of regulation, measurement, and interpretation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 296, R1473–R1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RM, 2002. Energetics and optimization of human walking and running: the 2000 Raymond Pearl memorial lecture. Am. J. Hum. Biol 14, 641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockway JM, 1987. Derivation of formulae used to calculate energy expenditure in man. Hum. Nutr. Clin. Nutr 41, 463–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke D, Schiller HH, 1976. Discharge pattern of single motor units in the tonic vibration reflex of the human triceps surae. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 39, 729–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow CC, Imhoff TT, Collins JJ, 1998. Enhancing aperiodic stochastic resonance through noise modulation. Chaos 8, 616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell LA, Lincoln NB, Radford KA, 2008. Somatosensory impairment after stroke: frequency of different deficits and their recovery. Clin. Rehabil. 22, 758–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtine G, Pozzo T, Lucas B, Schieppati M, 2001. Continuous, bilateral Achilles’ tendon vibration is not detrimental to human walk. Brain Res. Bull. 55, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin NJ, Lichtwark G, 2013. The use of ultrasound to study muscle-tendon function in human posture and locomotion. Gait Posture 37, 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin NJ, Peltonen J, Ishikawa M, Komi PV, Avela J, Sinkjaer T, Voigt M, 2010. Achilles tendon length changes during walking in long-term diabetes patients. Clin. Biomech. 25, 476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean JC, 2013. Proprioceptive feedback and preferred patterns of human movement. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev 41, 36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelan JM, Kram R, Kuo AD, 2001. Mechanical and metabolic determinants of the preferred step width in human walking. Proc. Biol. Sci 268, 1985–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund G, 1972. General features of vibration-induced effects on balance. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 77, 112–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris DJ, Sawicki GS, 2012. Human medial gastrocnemius force–velocity behavior shifts with locomotion speed and gait. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 977–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd LM, Holmes TC, Dean JC, 2014. Reduced effects of tendon vibration with increased task demand during active, cyclical ankle movements. Exp. Brain Res. 232, 283–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin GM, McCloskey DI, Matthews PBC, 1972. The contribution of muscle afferents to kinaesthesia shown by vibration induced illusions of movement and by the effects of paralysing joint afferents. Brain 95, 705–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin TM, Roberts TJ, Kram R, 2003. Metabolic cost of generating muscular force in human walking: insights from load-carrying and speed experiments. J. Appl. Physiol 95, 172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter LC, Hendrix EC, Dean JC, 2010. The cost of walking downhill: is the preferred gait energetically optimal? J. Biomech. 43, 1910–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M, Komi PV, Grey MJ, Lepola V, Bruggemann GP, 2005. Muscle– tendon interaction and elastic energy usage in human walking. J. Appl. Physiol 99, 603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanenko YP, Grasso R, Lacquaniti F, 2000. Influence of leg muscle vibration on human walking. J. Neurophysiol. 84, 1737–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeka J, Kiemel T, Creath R, Horak F, Peterka R, 2004. Controlling human upright posture: velocity information is more accurate than position or acceleration. J. Neurophysiol. 92, 2368–2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MP, Hayes SG, 2002. The exercise pressor reflex. Clin. Auton. Res 12, 429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavounoudias A, Gilhodes JC, Roll R, Roll JP, 1999. From balance regulation to body orientation: two goals for muscle proprioceptive information processing. Exp. Brain Res. 124, 80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroux A, Fung J, Barbeau H, 2002. Postural adaptation to walking on inclined surfaces: I. normal strategies. Gait Posture 15, 64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CL, Ferris DP, 2008. Walking with increased ankle pushoff decreases hip muscle moments. J. Biomech. 41, 2082–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtwark GA, Wilson AM, 2006. Interactions between the human gastrocnemius muscle and the Achilles tendon during incline, level, and decline locomotion. J. Exp. Biol 209, 4379–4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margaria R, 1968. Positive and negative work performances and their efficiencies in human locomotion. Int. Z. Angew. Physiol. Einschl. Arbeitsphysiol 25, 339–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minetti AE, Capelli C, Zamparo P, di Pramero PE, Saibene F, 1995. Effects of stride frequency on mechanical power and energy expenditure of walking. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc 27, 1194–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsch ED, Franz CO, Dean JC, 2012. The effects of gait strategy on metabolic rate and indicators of stability during downhill walking. J. Biomech. 45, 1928–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor SM, Donelan JM, 2012. Fast visual prediction and slow optimization of preferred walking speed. J. Neurophysiol. 107, 2549–2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliara R, Snaterse M, Donelan JM, 2014. Fast and slow processes underlie the selection of both step frequency and walking speed. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 2939–2946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribot-Ciscar E, Hospod V, Aimonetti JM, 2013. Noise-enhanced kinaesthesia: a psychophysical and microneurographic study. Exp. Brain Res. 228, 503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers DK, Bendrups AP, Lewis MM, 1985. Disrupted proprioception following a period of muscle vibration in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 57, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JP, Vedel JP, 1982. Kinaesthetic role of muscle afferents in man, studied by tendon vibration and microneurography. Exp. Brain Res. 47, 177–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenson J, Pires NJ, Loi HO, Pinniger GJ, Shannon DG, 2012. On the ascent: the soleus operating length is conserved to the ascending limb of the forcelength curve across gait mechanics in humans. J. Exp. Biol 215, 3539–3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryschon TW, Fowler MD, Wysong RE, Anthony AR, Balaban RS, 1997. Efficiency of human skeletal muscle in vivo: comparison of isometric, concentric, and eccentric muscle action. J. Appl. Physiol 83, 867–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaterse M, Ton R, Kuo AD, Donelan JM, 2011. Distinct fast and slow processes contribute to the selection of preferred step frequency during human walking. J. Appl. Physiol 110, 1682–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr A, McKeon B, Skuse N, Burke D, 1981. Cerebral potentials evoked by muscle stretch in man. Brain 104, 149–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen DG, Wilcox BJ, Niemi JB, Franz J, Kerrigan DC, D’Andrea SE, 2012. Baseline-dependent effect of noise-enhanced insoles on gait variability in healthy elderly walkers. Gait Posture 36, 537–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson SF, Sadeghi-Demneh E, Nester CJ, 2013. The effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on strength, proprioception, balance and mobility in people with stroke: a randomized controlled cross-over trial. Clin. Rehabil. 27, 785–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberger BR, Martin PE, 2007. Mechanical power and efficiency of level walking with different stride rates. J. Exp. Biol 210, 3255–3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deursen RW, Simoneau GG, 1999. Foot and ankle sensory neuropathy, proprioception, and postural stability. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther 29, 718–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschueren SM, Swinnen SP, Desloovere K, Duysens J, 2002. Effects of tendon vibration on the spatiotemporal characteristics of human locomotion. Exp. Brain Res. 143, 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellinghoff MA, Bunchman AM, Dean JC, 2014. Gradual mechanics-dependent adaptation of medial gastrocnemius activity during human walking. J. Neurophysiol. 111, 1120–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicka MM, Gilhodes JC, Roll JP, 1998. Vibration-induced postural post effects. J. Neurophysiol. 79, 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrugh MY, Radcliffe CW, 1978. Predicting metabolic cost of level walking. Eur. J. Appl. Phys 38, 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeni JA, Higginson JS, 2010. Gait parameters and stride-to-stride variability during familiarization to walking on a split-belt treadmill. Clin. Biomech. 25, 383–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeni JA, Richards JG, Higginson JS, 2008. Two simple methods for determining gait events during treadmill and overground walking using kinematic data. Gait Posture 27, 710–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]