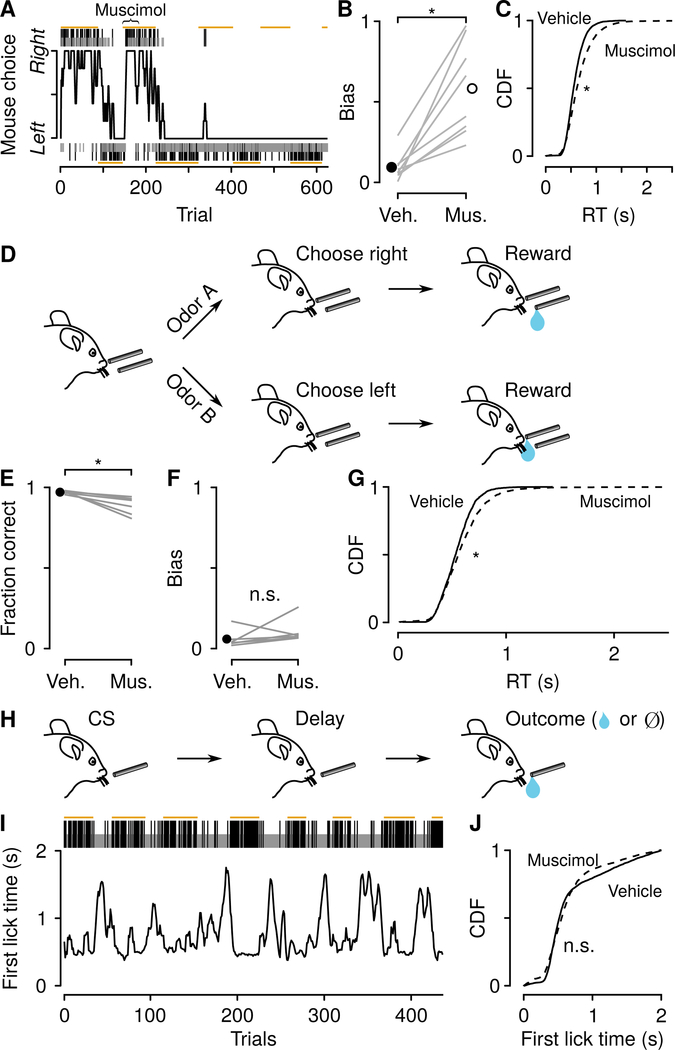

Figure 2: mPFC drives choice bias and response time.

(A) Example mPFC inactivation (muscimol injected during trials under curly brace). (B) Choice bias after vehicle and muscimol injections within and across mice (Wilcoxon signed rank test, P< 0.01). (C) Cumulative distributions of response times (RT) after vehicle (solid) and muscimol (dashed) injections (vehicle mean, 581±2 ms, median, 553 ms, muscimol mean, 672±4 ms, median, 618 ms, Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < 0.0001 ). (D) Two-alternative forced choice (2AFC) task, in which two odors signaled leftward or rightward choice. (E) Mean fraction correct in the 2AFC task, with vehicle or muscimol injections, within and across mice. Inactivation produced a small reduction in fraction of correct choices (Wilcoxon signed rank test, P < 0.05). (F) Inactivation did not bias choices in this task (Wilcoxon signed rank test, P > 0.3). (G) Inactivation increased RT (vehicle mean, 542±3 ms, median, 533 ms, muscimol mean, 586±5 ms, median, 556 ms, Wilcoxon rank sum, P< 0.0001). (H) Dynamic classical conditioning task, in which a single odor was followed by a delayed reward with a nonstationary probability. (I) Example session, in which latency to first lick following the odor varied with the probability of reward. Gold lines correspond to high-probability blocks. (J) Inactivation did not slow the latency to first lick (4 mice; vehicle mean, 691±6 ms, median, 517 ms, muscimol mean, 647±7 ms, median, 550 ms, Wilcoxon rank sum, P > 0.7 ). See also Figure S2.