Abstract

The long-anticipated high-resolution structures of the human melatonin G protein-coupled receptors MT1 and MT2, involved in establishing and maintaining circadian rhythm, were obtained in complex with two melatonin analogs and two approved anti-insomnia and anti-depression drugs using X-ray free electron laser serial femtosecond crystallography. The structures shed light on the overall conformation and unusual structural features of melatonin receptors, as well as their ligand binding sites and the melatonergic pharmacophore, thereby providing insights into receptor subtype selectivity. The structures revealed an occluded orthosteric ligand binding site with a membrane-buried channel for ligand entry in both receptors, and an additional putative ligand entry path in MT2 from the extracellular side. This unexpected ligand entry mode contributes to facilitating the high specificity with which melatonin receptors bind their cognate ligand and exclude structurally similar molecules such as serotonin, the biosynthetic precursor of melatonin. Finally, the MT2 structure allowed accurate mapping of type 2 diabetes-related single-nucleotide polymorphisms, where a clustering of residues in helices I and II on the protein-membrane interface was observed which could potentially influence receptor oligomerization. The role of receptor oligomerization is further discussed in light of the differential interaction of MT1 and MT2 with GPR50, a regulatory melatonin co-receptor. The melatonin receptor structures will facilitate design of selective tool compounds to further dissect the specific physiological function of each receptor subtype as well as provide a structural basis for next generation sleeping aids and other drugs targeting these receptors with higher specificity and fewer side effects.

Keywords: Melatonin, serotonin, G protein-coupled receptors, X-ray free electron laser, serial femtosecond crystallography, chronobiology, sleeping aids, diabetes

Graphical Abstract

The two melatonin G protein-coupled receptors, MT1 and MT2, are involved in the implementation and maintenance of circadian rhythms and are implicated in sleeping disorders, depression, cancer, and diabetes. Recent crystallographic studies provided the structural basis of ligand recognition and subtype selectivity at these receptors, and revealed an occluded binding site with a highly unusual ligand access mode via a narrow membrane-buried channel.

Introduction

Due to the earth’s rotation and the axial tilt relative to its orbital plane, organisms are subject to cycles of day and night, and the annual alternation of the seasons. Adaptation to these environmental cycles has led to coordination of periods of rest and activity, foraging behavior, mating and migration, known as circadian (and circannual) rhythm [1]. Physiological and behavioral accommodation of these rhythms rely on concerted responses on cellular and organism level, which has been attained by the evolution of a hierarchical network of biological oscillators that is able to generate an endogenous rhythmic behavior and provide synchronization to environmental cues. On the molecular level, this is achieved by the so-called clock genes, Clock, Bmal1, Per, and Cry, or their non-mammalian orthologs, which form the core of a network of complex interconnected autoregulatory feedback loops [2], modulating the rhythmic expression of clock-controlled genes (CCGs) that determine the temporal molecular state of the cell [3, 4]. This process per se is self-contained, and the free-running clock has to be synchronized to the environment in order to generate the circadian rhythm with exact 24-hour periodicity in a process called entrainment [5, 6].

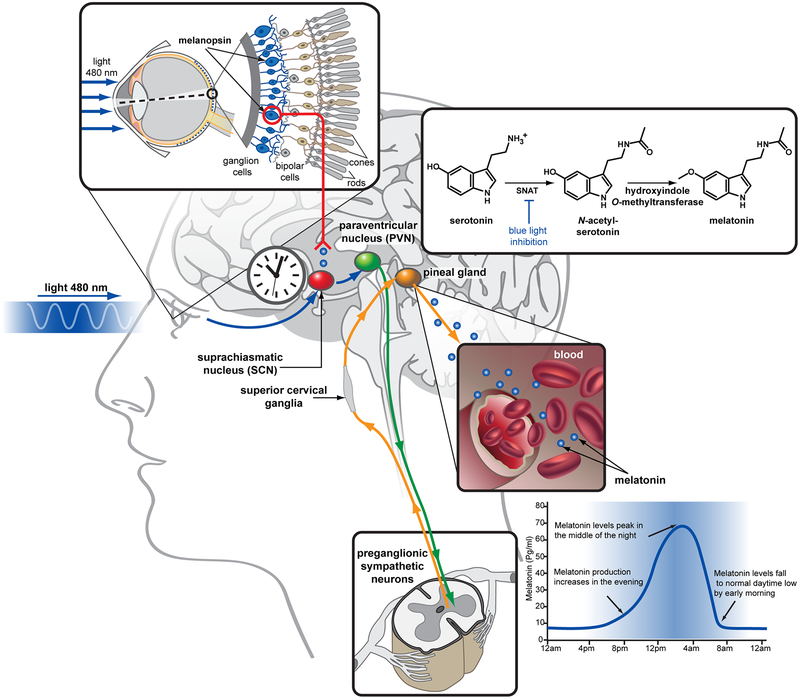

Synchronization is achieved by the light-dependent control of synthesis of the neurohormone melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine, MT) that acts as a diffusible “time messenger” [7] able to reset the molecular clock to provide coherence within central and peripheral oscillators [8, 9]. Melatonin is synthesized from serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) in the pineal gland of the animal brain by two enzymes, serotonin N-acetyl transferase (SNAT) and hydroxyindole O-methyltransferase [10] (Figure 1). It is then released into the third ventricle as well as into the blood stream, allowing it to control phase and/or amplitude of the expression of clock genes and CCGs in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the brain, and act on peripheral tissues [3, 11]. The synthesis of melatonin is tightly controlled by the SCN which integrates photoinformation from the retina and transmits it to the pineal gland through a multisynaptic pathway [12]. In humans, blue wavelength light (480 nm) detected by melanopsin leads to cessation of noradrenergic stimulation of SNAT phosphorylation, resulting in destabilization and proteolytic degradation of the enzyme, which, together with the short half-life of melatonin in blood, leads to high levels of melatonin at night and low levels of melatonin during the day. In diurnal species, high night-time levels of melatonin induce sleep, lower core body temperature and blood pressure, decreases glucose tolerance, and increase insulin resistance; in nocturnal species, the high night-time melatonin levels have an inverse effect, enabling increased activity levels during hours of darkness [3, 13].

Figure 1 |. Melatonin biosynthesis.

Serotonin is converted to melatonin in the pineal gland of the animal brain via two subsequent enzymatic reactions. The first step, N-acetylation, is catalyzed by serotonin N-acetyltransferase (SNAT), and inhibited by blue wavelength light signals transmitted from the retina via the suprachiasmic nucleus (SCN) resulting in a high level production of melatonin during the night and low level during the day. Melatonin is then released to the third ventricle and to the blood stream, allowing it to act on both brain and peripheral tissues where MT1 and MT2 are expressed. Among the diverse physiological functions of melatonin are regulation of body temperature and blood pressure, facilitating sleep.

Melatonin acts by activating two high-affinity melatonin receptors type 1A (MT1) and 1B (MT2) which are located in the SCN and expressed throughout different tissues of the body [14, 15], however, the differential role of each receptor subtype is not yet fully understood. A third, melatonin-related receptor (GPR50) has been identified in mammals that does not bind melatonin, but interacts with MT1 to negatively regulate its function [16]. A number of single nucleotide receptor variants exist – in particular of MT2, predominantly resulting in loss-of-function variants that have recently been implicated in type 2 diabetes (T2D) [17, 18]. MT1, MT2 and GPR50 belong to class A of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), a large family of cell-surface receptors that transduce extracellular messages into intracellular signals, thereby affecting gene expression and protein posttranslational modification which lead to cellular responses to external stimuli. In humans there are more than 800 distinct GPCRs that are able to respond to diverse ligands such as peptides, hormones, metabolites, proteins, ions and odorants [19]. Based on their sequence, GPCRs can be divided into five different classes: Rhodopsin or class A; Secretin or class B1; Adhesion or class B2; Glutamate or class C; and Frizzled/Taste2 or class F [20, 21].

MT receptors belong to the α-branch of class A GPCRs but they display some sequence features that distinguish them from other class A receptors [22–24]. For example, MT receptors contain the sequence NRY instead of E/D3.50RY, and NA7.50xxY instead of NPxxY (superscripts refer to Ballesteros-Weinstein residue numbering scheme [25]), which are both motifs involved in signal transduction [22–24].

Their exposed cell surface location and their broad involvement in all physiological processes make GPCRs privileged targets for therapeutic intervention, with over one third of FDA-approved drugs targeting GPCRs directly [26]. Due to the sleep-promoting properties of melatonin, MT1 and MT2 lend themselves as targets for sleeping aids [15, 27]. Insomnia and sleep disorders are highly prevalent in modern society and exacerbated by ubiquitous light pollution, shift work, and travel across time zones, all of which interfere with melatonin production and a “natural” circadian rhythm. Furthermore, melatonin production declines with age, contributing to a reduction in sleep quantity and quality that is detrimental to health [13, 28]. It therefore seems reasonable to supplement these declining endogenous melatonin levels, to supply a clock-resetting “timing pulse”, or for sleep-induction, by exogenous melatonin. Melatonin itself is non-sedating [13, 29], considered safe [30], and is readily available over-the-counter in the United States where it is one of the most popular supplements [31]. Melatonin, however, is rapidly cleared from the body, and its short half-life in blood (~45 mins) [32] has prompted the development of prolonged release formulations as well as synthetic melatonergics with improved properties such as the insomnia drug ramelteon [27, 33, 34]. Another approved drug acting on melatonin receptors is the atypical antidepressant agomelatine which in addition to its melatonergic agonism also displays 5-HT2C antagonism [35, 36]. This dual action of agomelatine is the exception (another rare example of ligands binding both MTR and 5-HTR being the psychedelic alkaloid 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine, 5-MeO-DMT) [37], and melatonin and serotonin receptors show high specificity for their cognate ligands despite their similar chemical structures (Figure 1), with melatonin and/or serotonin receptor binding affinity severely compromised by several orders of magnitude for all known dual ligands. There is a distinct lack of MT1/MT2 subtype-selective ligands, and most known MT receptor ligands are very similar to melatonin (i.e. possess indole or naphthalene-like scaffolds) and, generally, behave as agonists [15, 27, 38].

While the structures of serotonin receptors have been well studied [39–42], only recently have experimental structures of MT receptors been obtained [38, 43], providing the missing piece to understanding MT/5-HT polypharmacology and structural templates for rational design of tool compounds selective for melatonin-receptor subtypes, and more efficient drugs including safer sleeping aids.

Structure determination of MT receptors

Due to their low expression yields, high conformational flexibility, and instability outside their native membrane environment, GPCRs are notoriously difficult to crystallize [44]. The development of crystallization in lipidic cubic phase (LCP), a stabilizing membrane-mimetic environment, and microcrystallography techniques have facilitated considerable progress in membrane protein structure determination [45] – however, crystallizing GPCRs typically requires additional stabilization by protein engineering, i.e. truncations of flexible receptor parts, insertion of soluble protein domains (“fusion partners”) [46], and/or introduction of point mutations [47].

The structure determination of MT receptors was initially hampered by very low expression yields and strong propensity to aggregate upon extraction in detergent micelles, a necessary intermediate step in membrane protein crystallization. Initial receptor engineering included truncation of the N-terminus and the C-terminus, addition of N-terminal thermostabilized apocytochrome b562 (BRIL) fusion protein, and introduction of mutations D732.50N and F1163.41W to increase yield of MT1. Residue A7.50 was subsequently identified as important determinant of receptor stability. Restoring the canonical class A motif of NP7.50xxY by mutating A2927.50P greatly increased yield and monodispersity as determined by size exclusion chromatography, and allowed initial characterization by thermostability [48] and LCP-FRAP (Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching) assays that test receptor mobility in the lipid environment [49].

However, no crystals could be obtained, so additional stabilizing point mutations were identified by systematic comparison of sequence conservation profiles of MT receptors to other class A GPCRs using an automated method [38], and reverting identified MT receptor residues to class A consensus accordingly. After a further glycine-to-alanine scan and mutation of the tryptophan toggle switch [24], a stabilized MT1 construct (MT1-CC) was obtained carrying nine point mutations (D732.50N, L95ECL1F, G1043.29A, F1163.41W, N1243.49D, C1273.52L, W2516.48F, A2927.50P, N2998.47D) that were ultimately essential for high-resolution structure determination. While crystallization trials of this MT1 construct were still unsuccessful, the introduction of an additional rubredoxin fusion partner into the ICL3 of a correspondingly mutated MT2 construct (i.e. using a double fusion approach) (MT2-CC) resulted in initial crystals that could be optimized to diffract to 3.3 Å using a 10 μm minibeam at the GM/CA@APS beamline, Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory. Utilizing an ICL3 fusion of the catalytic domain of glycogen synthase of Pyrococcus abyssi (PGS) [50] instead of the N-terminal BRIL eventually facilitated crystallization of MT1, but even optimized crystals of up to 50 μm size in maximum dimension were insufficient to yield better than 5–6 Å diffraction at APS and other microfocus synchrotron sources.

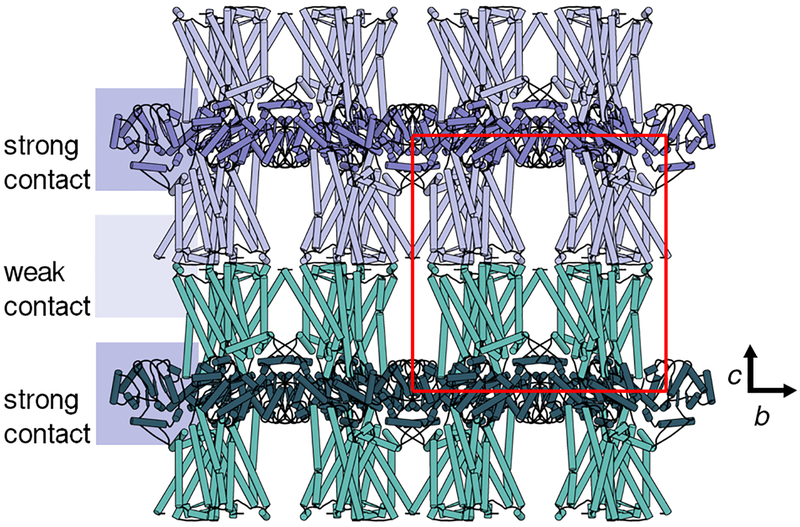

The superior brightness and extremely short duration of X-ray free electron laser (XFEL) pulses allows the collection of diffraction data at room temperature before the onset of radiation damage. This allows the use of smaller micrometre-sized crystals that have fewer imperfections, and the combination of factors results in improved resolution compared to using a synchrotron source [44, 51]. Since crystals are ultimately destroyed by the strong beam, XFEL data are collected in a one-crystal-per-shot approach (serial femtosecond crystallography, SFX [52]). In case of GPCRs, crystals are typically delivered to the intersection with the XFEL beam by injection within their growth medium using viscous media LCP injectors [53, 54]. During the last five years, about a dozen novel GPCR structures have been determined benefiting from XFEL data collection [51, 55, 56]. In the case of MT receptors, using the CXI beamline [57] at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) we were able to obtain structures of MT1 and MT2 bound to different agonists at resolutions between 2.8 and 3.3 Å [38, 43, 58] (Table 1) – we attribute the remarkable gain in resolution for MT1 at XFEL sources to the specific packing of the receptor in alternating layers with strong and weak contacts (Figure 2), as cryo-cooling causes contraction of the crystal lattice, introducing defects in the lattice hence limiting resolution. This hypothesis was recently supported by experiments at the 1 μm focus FMX beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source – II (NSLS-II), Brookhaven National Laboratory; worse diffraction was obtained from crystals identical to those used at the XFEL despite using a similar beam size and total exposure dose, probably because the crystals had to be cryo-cooled (unpublished results).

Table 1 |. Melatonin receptor crystal structures.

2-phenylmelatonin (2-pmt; CHEMBL [37] identifier CHEMBL15060); ramelteon (ram; CHEMBL1218); 2-iodomelatonin (2-iodo; CHEMBL289233); agomelatine (CHEMBL10878). CC, crystallization construct. Data collection time and protein amount used for structure determination are approximate.

| Receptor | Ligand | Construct | PDB | Resolution (Å) | Data collection (min) | Number of crystals | Protein amount (μg) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT1 |

ram |

MT1-CC | 6me2 | 2.8 | 95 | 46,679 | 370 | [38] |

| MT1 |

2-pmt |

MT1-CC | 6me3 | 2.9 | 200 | 99,897 | 290 | [38] |

| MT1 |

2-iodo |

MT1-CC | 6me4 | 3.2 | 70 | 21,038 | 260 | [38] |

| MT1 |

agomelatine |

MT1-CC | 6me5 | 3.2 | 65 | 42,423 | 240 | [38] |

| MT1 | agomelatine to 2-pmt | MT1-CC | 6ps8 | 3.3 | 136 | 87,453 | 440 | [58] |

| MT2 | 2-pmt | MT2-CC | 6me6 | 2.8 | 280 | 31,677 | 670 | [43] |

| MT2 | 2-pmt | MT2-CC-H208A | 6me7 | 3.2 | 55 | 28,130 | 540 | [43] |

| MT2 | 2-pmt | MT2-CC-(D86N)D | 6me8 | 3.1 | 40 | 20,704 | 410 | [43] |

| MT2 | ram | MT2-CC | 6me9 | 3.3 | 100 | 28,834 | 540 | [43] |

Figure 2 |. Crystallographic packing of MT1.

The receptor was crystallized in tetragonal space group P4 21 2 with unit cell (red) dimensions of a=b=122.3 Å and c=122.8 Å (PDB identifier 6me2). Symmetry mates were found to pack in alternating layers mediated by head-to-head receptor (light blue, teal) weak contacts and strong contacts mediated by intracellular fusion proteins (dark blue, green). This figure has been generated using PyMOL.

The SFX mode of data collection results in acquisition of a large number of still diffraction images of randomly oriented crystals, requiring tailored data processing methods for indexing, merging, and scaling [59, 60]. In case of MT1, correct indexing and merging were greatly complicated by the fact that for the observed tetragonal symmetry in space group P 4 21 2 the length of the unique unit cell axis (c) was very close to the length of the redundant unit cell axes (c≈a=b) (Figure 2), leading to an indexing ambiguity that manifests as apparent pseudomerohedral crystal twinning and that had to be resolved by at least two consecutive iterations of the ambigator tool in CrystFEL with the indexing ambiguity operator (k, l, h) [38].

Structures of human MT receptors and their implications for cognate ligand specificity

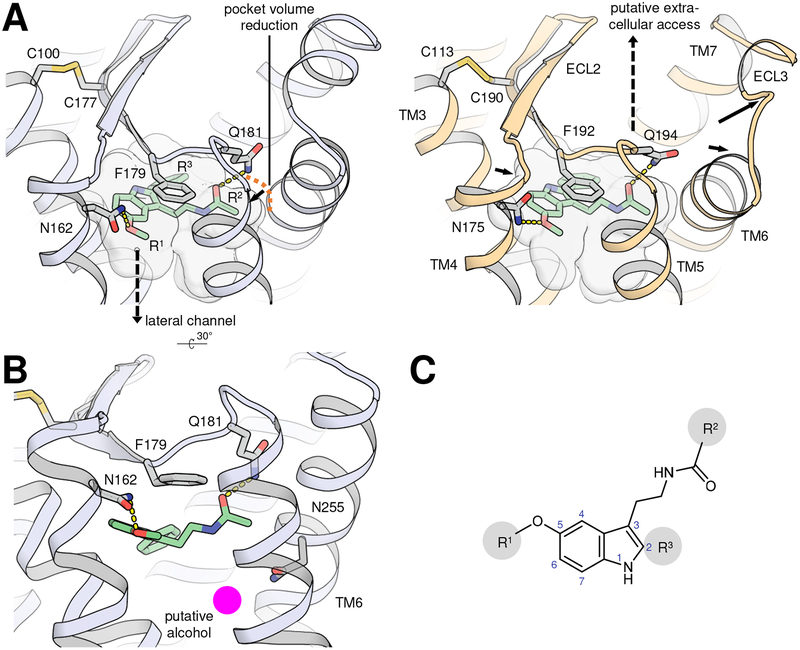

MT receptors display the canonical 7TM fold of class A GPCRs with a transmembrane heptahelical bundle flanked by N- and C-termini and a short amphiphilic helix 8, and interspersed by three intracellular (ICL) and three extracellular loops (ECL) [38, 43]. The MT receptors bound to four different agonists (2-phenylmelatonin (2-pmt), 2-iodomelatonin, ramelteon, and agomelatine) were crystallized in an inactive conformation, which is not uncommon in absence of their downstream interaction partners, especially in cases where the ligand binding site and activation-related conformational changes on the intracellular site are only loosely coupled, such as observed for β2AR [51]. Furthermore, the receptors were rendered functionally inactive by the inclusion of thermostabilizing point mutations essential for crystallizing them, presumably contributing to their observed inactive conformation [38, 43, 44], potentially by further uncoupling ligand binding site from intracellular receptor region. Although the overall receptor conformation is inactive, we do believe the binding site is accurately captured, and the agonist-binding mode is correct and relevant. When comparing agonist-bound inactive and fully active receptor conformations of other GPCRs, no drastic changes in ligand binding mode surpassing activation-induced binding site compaction accompanied by ligand-receptor hydrogen bond shortening have been observed [61]. The MT receptor binding pockets observed in the structures are very compact and occluded, complementing the low molecular weight of melatonergic ligands. Receptor-ligand interactions are anchored by two hydrogen bonds with residues (MT1/MT2) N162/N1754.62 and Q181/Q194ECL2 and a stacking interaction with F179/F192ECL2 (Figure 3A). The rest of the pocket is mostly hydrophobic including a side-pocket that can accommodate ligand substituents at the indole 2-position (Figure 3C).

Figure 3 |. Differences and similarities of MT receptor binding sites.

A, Ligand-binding sites of 2-pmt-bound MT1 (light blue, left; PDB identifier 6me3) and MT2 (light orange, right; PDB 6me6) receptors are shown as closed surfaces with receptors in cartoon representation. 2-pmt (green) as well as the three key ligand-coordinating residues and the disulfide bridge are shown as sticks with blue nitrogens, red oxygens, and yellow sulfurs. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by yellow dashed lines. Amino-acid sequence and conformations within the binding site are remarkably conserved between receptor subtypes; the most apparent differences include the smaller volume in MT1 (710 Å3) compared to MT2 (766 Å3), mostly due to a small compaction around the R2 tail of the ligand (orange dash curve with a black arrow), as well as narrowing of the lateral channel (dashed black arrow) and expansion of the ECL access in MT2 (solid black arrows). B, position of putative alcohol (magenta) close to residue N255 in binding site of MT1. See Figure 3C for definition of melatonin substituents R1, R2, and R3. C, chemical structure of melatonin. Heteroatom numbering based on the indole numbering-scheme are indicated as blue digits, and positions with variable substituents in melatonin derivatives are indicated by R1, R2, and R3. This figure has been generated using PyMOL.

The observation of a small unmodeled electron density near the ligand in MT1, close to N2556.52 and absent in MT2, correlates with the different role of this residue in the activation of the respective receptor subtype [38, 43] (Figure 3B). We tentatively proposed that in MT1 this position is occupied by propan-2-ol which was used as an essential crystallization additive – the ability of the receptor to accommodate alcohols with potential implications on ligand binding and receptor function warrants further investigation.

MT receptors possess a unique [38] YPYP motif that induces a bulged kink in TM2 and appears to be important for receptor stability. Involvement of a histidine residue (H3.24) in a hydrogen bond with YPYP would facilitate a pH dependent mechanism of inter-helical packing between TM2 and TM3, but this hydrogen bond was not found to be of importance in functional assays carried out under physiological conditions [38].

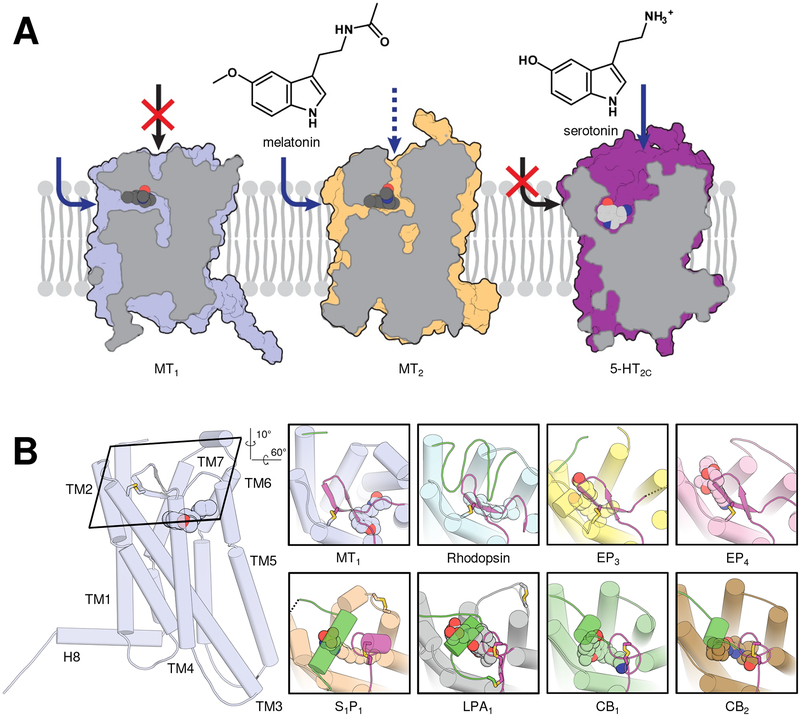

The most surprising feature of the MT receptor structures is the presence of a lateral channel between TM4 and TM5 which allows ligand access to the orthosteric site with ECL2 forming a tight lid anchored by the conserved disulfide bridge of class A receptors (C100/C1133.25 to C177/C190ECL2), and a number of stabilizing interactions between ECL2 and TM1, TM2 and TM7 (Figure 4). This channel is slightly wider and more pronounced in MT1 compared to MT2. However, in MT2 the ECL2-lid appears less tight, mainly resulting from a slight outward movement of the MT2 backbone around the tip of TM6 and ECL3 (Figure 3B), leading to fewer van-der-Waals interactions of this region with ECL2, thereby providing an additional potential route of ligand access, as also supported by kinetic ligand disassociation experiments [43].

Figure 4 |. Extracellular occlusion in class A GPCRs.

A, surface section of melatonin receptors MT1 (left) and MT2 (middle) compared to serotonin receptor 5-HT2C (right, PDB identifier 6bqg). Lipid bilayer indicated as light grey schematic. Ligand access routes to respective receptors are indicated by blue arrows. B, conformation of extracellular parts of MT1 (left and first insert; PDB 6me2) compared to rhodopsin (PDB 1u19) and lipid receptors (prostaglandin receptors EP3 and EP4, PDB identifiers 6m9t and 5ywy; sphingosine-1-phospate receptor S1P1, PDB 3v2w; lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA1, PDB 4z35; cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2, PDBs 5xr8 and 5zty) shown as inserts (N-terminus, green; ECL2, magenta; disulfides, sticks with yellow sulfurs). Ligands are shown as spheres with blue nitrogens and red oxygens, unresolved non-terminal extracellular residues as dashed lines, and helices as cylinders. Rotation angles are approximate. This figure has been generated using PyMOL.

GPCRs have evolved different ways to control access to the binding site involving combinations of extracellular loops and/or receptor N-terminus [62]. A similarly closed-off binding site and/or lateral channel has not previously been observed in GPCRs other than rhodopsin and lipid receptors. Lipid receptors are devoid of unifying sequential and structural features because they bind very different ligands and are therefore scattered across the GPCR phylogenic tree [56]. For example, cannabinoid, lysosphingolipid, and prostaglandin receptors belong to the α-branch of class A GPCRs; leukotriene receptors to branches γ and δ; and free fatty acid receptors to the δ-branch). Even within the α-branch of class A, lysophosphatidic acid, sphingosine-1-phosphate and cannabinoid receptors [63–66], which lack the canonical class A disulfide bridge between TM3 and ECL2, close off their binding sites mostly using their N-terminus with minor ECL2 contributions. In contrast, prostaglandin receptors [55, 67] and rhodopsin [68] display a tight lid formed from ECL2 with a β-hairpin constrained to TM3 by the canonical class A disulfide bridge. The ECL2 backbone and disulfide location of MT receptors overlap remarkably well with that of solved prostaglandin and rhodopsin structures (Figure 4B).

It should be noted that while published homology models of MT receptors failed to capture important structural features of the receptors, accurate ligand binding modes and ligand interacting residues, the earliest, rhodopsin-based homology models [34, 69, 70] would have been preferred templates for modeling the MT1 ECL2-lid. The importance of ECL2 for the binding of ligands to the melatonin receptor has only recently been fully appreciated [71]. The MT receptor lateral channel is lined by hydrophobic residues and opens up to the membrane interior close to a conserved histidine residue (H195/H2085.46) that previously, based on mutagenesis data, had been hypothesized to directly interact with ligand [15, 72, 73], although observed effects on binding affinity had been minor. We find that this residue does not interact with ligands in our structures, even though in a docking model with a bitopic ligand it does make an interaction which could point to the existence of a transient interaction during binding of monotopic ligands or their transition through the channel [38, 43]. It appears that the indirect involvement of this histidine residue in ligand binding as well as the underestimation of ligand contacts with ECL2 has misguided MT receptor homology models until recently [71, 74], illustrating the value of experimental structure determination over the reliance on receptor models based on distant templates.

Comparison of the entrances to the orthosteric binding site in MT receptors and serotonin receptors suggests how the lipid bilayer itself acts as a “selectivity filter” that precludes charged or polar ligands (such as serotonin) from entering the melatonin binding site (Figure 4A). This could be an important mechanism to ensure orthogonal receptor function in presence of both ligands, or when MT and 5-HT receptors are co-expressed. Furthermore, the orientation of the ligand core in melatonin and serotonin receptors is perpendicular to one another, and the ligand engages unrelated residues in the two binding sites that share a very low level of sequence conservation (e.g. only 1 out of 19 residues are conserved between MT1 and 5-HT2C receptor binding sites), correspondingly missing the key interactions made with the MT receptors by the methoxy and alkylamide moieties of melatonin [38].

MT receptor subtype selectivity

The MT receptors are targeted by multiple non-selective therapeutic drugs including ramelteon, agomelatine and tasimelteon [15, 37]. However, obtaining subtype specific compounds has been incredibly challenging, given the high degree of conservation in the binding pocket (20 out of 21 between MT1 and MT2 are conserved) [38, 43]. To date, the majority of subtype-selective compounds prefer MT2, with a few exceptions, mainly for bitopic ligands, which show slight selectivity (<10 fold) towards MT1 [37, 43, 75, 76]. Our recent MT1 and MT2 structures provide a structural basis of subtype selectivity where it becomes evident that selectivity is obtained through mainly three routes. Firstly, the slightly larger binding pocket of MT2 serves to accommodate bulkier substituents in the R2 and R3 positions as opposed to MT1 (Figure 3). Secondly, longer ligand alkyl chains in the R2 position are better accommodated in MT2, where they dock in the more energetically favorable “tail up” position (towards Q194ECL) rather than the more suboptimal “tail down” mode as they would in MT1. Thirdly, compounds with substituents in the R1 position are more easily accommodated in the MT1 receptor due to the slightly wider ligand entry channel, which is also in line with our experimental findings for bitopic ligands [38, 43]. Indeed, bitopic melatonergic compounds have long been studied as a means to achieve subtype selectivity, and in the context of melatonin receptor dimers (see below) [75, 77]. Selectivity may also be achieved through exploiting the additional ligand entry pathway in the extracellular domain of MT2, where potentially more hydrophilic compounds can enter (Figure 4A). The availability of MT1 and MT2 crystal structures could facilitate identification of novel ligand scaffolds with new properties such as an increased subtype selectivity.

The channel and its entrance represent potential allosteric sites with particular promise for the design of MT1 specific compounds and antagonists which are currently lacking [15, 27]. The structures will also enable the design of tool compounds such as fluorescently-labeled bitopic ligands, with the fluorescent moiety engineered to pass out through the channel so it does not significantly affect ligand affinity. In any case, rational drug design should take the presence of the lateral access channel and the resulting non-trivial ligand entry mechanism into account – rather than merely improving ligand complementarity to the binding site through maximizing docking scores. The ligand needs to penetrate the membrane surface and then pass through the entrance channel before binding in the orthosteric binding pocket. Optimizing the physicochemical properties and dimensions of potential lead compounds could enhance the chances of success of a rational drug design campaign.

MT receptor variants in type 2 diabetes and relevance of GPCR dimerization

The importance of MT receptors in the regulation of circadian rhythm and sleep patterns has long been appreciated. However, recent research has suggested a more direct involvement of MT2 in T2D [17, 18]. Several non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been described that impair receptor function and are associated with an increased risk of T2D [17, 18]. Mapping these SNPs on to the MT2 structure broadly groups most of these variants into three categories: (i) variants within or close to the ligand binding site, or canonical class A motifs; (ii) variants located on the solvent exposed intracellular receptor surface; and (iii) variants located on the lipid exposed intramembrane receptor surface (Figure 5).

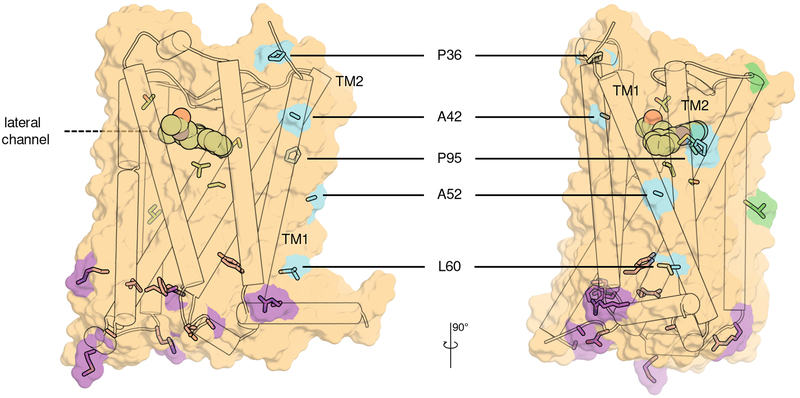

Figure 5 |. Location of T2D-related single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on the MT2 structure.

Receptor shown in cartoon representation with solvent-accessible surface (PDB identifier 6me6). Ligand 2-pmt shown as spheres, and SNPs shown as sticks with blue nitrogens and red oxygens. SNPs located in the TM1-TM2 region of the receptor (P36, A42, A52, L60, and P95) and potentially involved in receptor oligomerization or interactions with other membrane partners are colored cyan, while SNPs clustered in the intracellular region responsible for binding transducers are colored magenta, or green otherwise. This figure has been generated using PyMOL.

While variants in categories (i) and (ii) most likely impair receptor function by interfering with ligand binding, coupling of the binding site to the intracellular region, or interaction with G proteins and/or β-arrestins, those in category (iii) can be presumed to have a more indirect effect than just impairing the minimal functional signaling complex (agonist-receptor-transducer). Strikingly, a cluster of variants is found in TM1 (P36S, A42P, A52T, and L60R) and TM2 (P95L, of the YPYP motif) (Figure 5), one of the proposed interfaces for the formation of dimers in other receptors [78]. Recently, GPCR dimerization interfaces have been proposed to contain multiple epitopes and dynamically interconvert between different dimer conformations (“rolling dimer” model) [78], indicating that the existence of one relevant interface does not preclude the existence of another (see below). An alternative effect of diverging lipid-exposed receptor residues could be to affect receptor thermostability due to entropic effects [79] that ultimately influence receptor surface dwell-time or signaling ability.

Indeed, MT receptors have long been known to form homo- and heterodimers [16, 80]. Recently, symmetrical bitopic ligands with long spacers (16–24 atoms) have been described to bind MT receptor dimers [81], consistent with a symmetrical receptor dimerization interface across TM4/TM5 that brings the lateral channels into mutual proximity. While dimerization of different class A GPCRs has been extensively studied in vitro, its relevance in vivo is still a matter of debate [82]. In the case of MT receptors, fluorescence in situ hybridization data in murine retinas, where MT1 and MT2 are co-expressed, suggests in vivo functional relevance for receptor dimerization [83]. Modulation of receptor activity via oligomerization represents an additional layer of physiological regulation, and the distinct signaling properties of GPCR oligomeric complexes constitute a novel target for therapeutic intervention [82]. Impairment of interaction with other GPCRs, and non-GPCR transmembrane proteins, through the disruption of the TM1/TM2 interface therefore represents a plausible mechanism of impairment of MT2 by these T2D-associated genetic variants. A more detailed characterization of MT2-interacting proteins subject to this impairment could therefore be an important step towards a complementary therapeutic intervention targeting T2D.

GPR50 and allosteric modulation of ligand binding and signaling of MT receptors

MT1 and MT2 are not only known to homo- and heterodimerize with one another, but they have also been found to interact with other GPCRs. The melatonin-related receptor GPR50 shares about 50% amino acid sequence identity with MT1 and MT2. It does not, however, bind melatonin, and no endogenous or synthetic ligands for this receptor have been found.

GPR50 has been shown to heterodimerize with both MT1 and MT2, however, this interaction was reported to prevent melatonin binding and downstream signaling only of MT1, but not MT2 [16]. The large ~300 residue C-terminus of GPR50 (GPR50-Cter) is essential for this inhibition, perhaps through sterically blocking the MT1 G protein and β-arrestin binding sites [16], but receptor heterodimerization still occurs in absence of GPR50-Cter, indicating an extended interaction interface most likely involving transmembrane helices.

Interestingly, GPR50 ligand binding and activation can be restored by transplanting ECL2 and parts of TM6 from MT1 [71], suggesting that GPR50 has only recently lost the ability to bind melatonin while still being subject to evolutionary pressure to maintain its ligand-independent regulatory role as a melatonin co-receptor [84]. The inability of GPR50 to inhibit MT2 is remarkable given the high extent of structural similarity between MT1 and MT2, and that MT2/GPR50 heterodimerization still occurs [16]. This points to a different mode of interaction between MT1/GPR50 and MT2/GPR50. GPR50 could inhibit ligand binding of MT1 in an allosteric GPR50-Cter dependent way by inducing a conformational change in the ligand binding site of MT1, or by preventing ligand access to the binding site. The MT1 and MT2 crystal structures will inspire additional experiments to unravel the differential effect of GPR50 on the two receptor subtypes.

The non-trivial access mode of ligands to MT receptors through the lateral access channel makes the interface between TM4 and TM5 a possible allosteric site for the regulation of MT1 function by interacting proteins, or even lipids; MT2 could be affected differently because of the additional extracellular ligand entry mode.

Concluding remarks and future outlook

The atomic structures of the two human melatonin receptors MT1 and MT2 obtained in complex with several agonists revealed a membrane-buried ligand entry channel as well as an additional narrow opening in the ECL part of MT2. Furthermore, comparison to serotonin receptors reveals that, despite their endogenous ligand similarities, the binding site residues engaged in ligand binding are completely unrelated to those of the MT receptors. Further investigations of the dynamics of ECLs by NMR or fluorescence approaches could shed additional light on the ligand entry mechanism and along with genomics analysis provide insights into the order of evolutionary events that led to ECL closure and binding site changes.

Due to the inherent flexibility of the MT receptors, several stabilizing point mutations had to be engineered for crystallization purposes, resulting in structures that captured receptors in an agonist-bound inactive state. In order to fully understand the activation mechanism of these receptors, both the inactive antagonist-bound and the fully active G protein- or β-arrestin-bound active state structures would be highly desirable. While crystallization of GPCR signaling complexes have been extremely challenging [22, 85], recent advancements in single-particle cryo-EM have paved the way to their structure determination in a more routine way using more native-like receptors [86]. Fully active and inactive state structures might also help to answer the question why so disproportionally few antagonists have been identified for MT receptors. A structure in complex with a bitopic ligand would validate the functional relevance of the lateral ligand access channel [38]. Further worthwhile targets for structure determination that could be attempted by crystallography or cryo-EM are homo- and heterodimers of MT receptors, in particular those for MT1/MT2 (potentially aided by the recently described class of bitopic ligands with long spacers that target MT receptor dimers [81]), MT1/GPR50, and MT2/GPR50, as well as heteromers of MT/5-HT receptors relevant for the pharmacological mode of action of the antidepressant agomelatine and which have been found to display signaling bias [87].

The identification of the unique ligand access in MT receptors, mediated predominantly by the membrane-buried lateral channel, presents an opportunity for the design of selective compounds, and development of improved fluorescent tool compounds to decipher the relative contribution of receptor subtypes to their biological function. In the future, the structures of MT receptors will prove their worth by facilitating the structure-based discovery of new ligand chemotypes with improved subtype selectivity and new efficacy profiles. Mirroring the pleiotropic nature of melatonin, and the involvement of its receptors in a large number of distinct physiological processes, this new generation of melatonergic ligands has the potential to be transformative beyond chronobiology, and have a large positive impact on human health and wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

We thank Y. Kadyshevskaya for help with preparing illustrations. This work has been funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R35 GM127086, the National Science Foundation (NSF) BioXFEL Science and Technology Center 1231306 (B.S., V.C.), EMBO ALTF 677-2014 (B.S.), HFSP long-term fellowship LT000046/2014-L (L.C.J.), and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Swedish Research Council (L.C.J.). Crystallographic data were collected at the LCLS, a National User Facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the US Department of Energy and supported by the US Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515.

Abbreviations

- 2-pmt

2-phenylmelatonin

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin)

- APS

Advanced Photon Source

- BRIL

thermostabilized apocytochrome b562

- CC

crystallization construct

- CCG

clock-controlled genes

- Cter

C terminus

- CXI

coherent X-ray imaging beamline

- ECL

extracellular loop

- FMX

Frontier Microfocusing Macromolecular Crystallography beamline

- FRAP

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GPR50

melatonin-related receptor

- LCLS

Linac Coherent Light Source

- LCP

lipidic cubic phase

- MT

melatonin

- MT1

melatonin receptor type 1A

- MT2

melatonin receptor type 1B

- NSLS-II

National Synchrotron Light Source II

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- PGS

catalytic domain of glycogen synthase of Pyrococcus abyssi

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- SFX

serial femtosecond crystallography

- SNAT

serotonin N-acetyl transferase

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- TM

transmembrane helix

- XFEL

X-ray free electron laser

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Aschoff J (1965) Circadian Rhythms in Man. Science 148, 1427–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi JS (2004) Finding new clock components: past and future. J Biol Rhythms 19, 339–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cipolla-Neto J & Amaral FGD (2018) Melatonin as a Hormone: New Physiological and Clinical Insights. Endocr Rev 39, 990–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ueda HR, Hayashi S, Chen W, Sano M, Machida M, Shigeyoshi Y, Iino M & Hashimoto S (2005) System-level identification of transcriptional circuits underlying mammalian circadian clocks, Nat Genet 37, 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aschoff J (1981) Freerunning and Entrained Circadian Rhythms in Biological Rhythms (Aschoff J, ed) pp. 81–93, Springer US, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sack RL, Brandes RW, Kendall AR & Lewy AJ (2000) Entrainment of free-running circadian rhythms by melatonin in blind people. N Engl J Med 343, 1070–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erren TC & Reiter RJ (2015) Melatonin: a universal time messenger. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 36, 187–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arendt J & Skene DJ (2005) Melatonin as a chronobiotic. Sleep Med Rev 9, 25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardeland R, Cardinali DP, Srinivasan V, Spence DW, Brown GM & Pandi-Perumal SR (2011) Melatonin--a pleiotropic, orchestrating regulator molecule. Progr Neurobiol 93, 350–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardeland R, Pandi-Perumal SR & Cardinali DP (2006) Melatonin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 38, 313–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagy AD, Iwamoto A, Kawai M, Goda R, Matsuo H, Otsuka T, Nagasawa M, Furuse M & Yasuo S (2015) Melatonin adjusts the expression pattern of clock genes in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and induces antidepressant-like effect in a mouse model of seasonal affective disorder. Chronobiol Int 32, 447–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perreau-Lenz S, Kalsbeek A, Garidou ML, Wortel J, van der Vliet J, van Heijningen C, Simonneaux V, Pevet P & Buijs RM (2003) Suprachiasmatic control of melatonin synthesis in rats: inhibitory and stimulatory mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci 17, 221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zisapel N (2018) New perspectives on the role of melatonin in human sleep, circadian rhythms and their regulation, Br J Pharmacol 175, 3190–3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubocovich ML & Markowska M (2005) Functional MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors in mammals. Endocrine. 27, 101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jockers R, Delagrange P, Dubocovich ML, Markus RP, Renault N, Tosini G, Cecon E & Zlotos DP (2016) Update on melatonin receptors: IUPHAR Review 20, Brit J Pharmacol 173, 2702–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levoye A, Dam J, Ayoub MA, Guillaume JL, Couturier C, Delagrange P & Jockers R (2006) The orphan GPR50 receptor specifically inhibits MT1 melatonin receptor function through heterodimerization. EMBO J 25, 3012–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karamitri A, Plouffe B, Bonnefond A, Chen M, Gallion J, Guillaume JL, Hegron A, Boissel M, Canouil M, Langenberg C, Wareham NJ, Le Gouill C, Lukasheva V, Lichtarge O, Froguel P, Bouvier M & Jockers R (2018) Type 2 diabetes-associated variants of the MT2 melatonin receptor affect distinct modes of signaling. Sci Signal 11, eaan6622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnefond A, Clement N, Fawcett K, Yengo L, Vaillant E, Guillaume JL, Dechaume A, Payne F, Roussel R, Czernichow S, Hercberg S, Hadjadj S, Balkau B, Marre M, Lantieri O, Langenberg C, Bouatia-Naji N, Charpentier G, Vaxillaire M, Rocheleau G, Wareham NJ, Sladek R, McCarthy MI, Dina C, Barroso I, Jockers R & Froguel P (2012) Rare MTNR1B variants impairing melatonin receptor 1B function contribute to type 2 diabetes, Nat Genet 44, 297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroeze WK, Sheffler DJ & Roth BL (2003) G-protein-coupled receptors at a glance, J Cell Sci 116, 4867–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fredriksson R, Lagerstrom MC, Lundin LG & Schioth HB (2003) The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families. Phylogenetic analysis, paralogon groups, and fingerprints. Mol Pharmacol 63, 1256–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Attwood TK & Findlay JB (1994) Fingerprinting G-protein-coupled receptors. Protein Eng 7, 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SG & Kobilka BK (2009) The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors, Nature 459, 356–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rovati GE, Capra V & Neubig RR (2007) The highly conserved DRY motif of class A G protein-coupled receptors: beyond the ground state. Mol Pharmacol 71, 959–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trzaskowski B, Latek D, Yuan S, Ghoshdastider U, Debinski A & Filipek S (2012) Action of molecular switches in GPCRs--theoretical and experimental studies. Curr Med Chem 19, 1090–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballesteros JA & Weinstein H (1995) Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors in Methods in Neurosciences (Stuart CS, ed) pp. 366–428, Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos R, Ursu O, Gaulton A, Bento AP, Donadi RS, Bologa CG, Karlsson A, Al-Lazikani B, Hersey A, Oprea TI & Overington JP (2017) A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 16, 19–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zlotos DP (2012) Recent progress in the development of agonists and antagonists for melatonin receptors. Curr Med Chem 19, 3532–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hood S & Amir S (2017) The aging clock: circadian rhythms and later life. J Clin Invest 127, 437–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zisapel N (2007) Sleep and sleep disturbances: biological basis and clinical implications. Cell Mol Life Sci 64, 1174–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seabra ML, Bignotto M, Pinto LR Jr. & Tufik S (2000) Randomized, double-blind clinical trial, controlled with placebo, of the toxicology of chronic melatonin treatment. J Pineal Res 29, 193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM & Nahin RL (2015) Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Report (79), 1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harpsoe NG, Andersen LP, Gogenur I & Rosenberg J (2015) Clinical pharmacokinetics of melatonin: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 71, 901–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owen RT (2006) Ramelteon: profile of a new sleep-promoting medication. Drugs Today 42, 255–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uchikawa O, Fukatsu K, Tokunoh R, Kawada M, Matsumoto K, Imai Y, Hinuma S, Kato K, Nishikawa H, Hirai K, Miyamoto M & Ohkawa S (2002) Synthesis of a novel series of tricyclic indan derivatives as melatonin receptor agonists. J Med Chem 45, 4222–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guardiola-Lemaitre B, De Bodinat C, Delagrange P, Millan MJ, Munoz C & Mocaër E (2014) Agomelatine: mechanism of action and pharmacological profile in relation to antidepressant properties. Brit J Pharmacol 171, 3604–3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millan MJ, Gobert A, Lejeune F, Dekeyne A, Newman-Tancredi A, Pasteau V, Rivet JM & Cussac D (2003) The novel melatonin agonist agomelatine (S20098) is an antagonist at 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptors, blockade of which enhances the activity of frontocortical dopaminergic and adrenergic pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306, 954–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bento AP, Gaulton A, Hersey A, Bellis LJ, Chambers J, Davies M, Kruger FA, Light Y, Mak L, McGlinchey S, Nowotka M, Papadatos G, Santos R & Overington JP (2014) The ChEMBL bioactivity database: an update. Nucleic Acids Res 42, D1083–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stauch B, Johansson LC, McCorvy JD, Patel N, Han GW, Huang XP, Gati C, Batyuk A, Slocum ST, Ishchenko A, Brehm W, White TA, Michaelian N, Madsen C, Zhu L, Grant TD, Grandner JM, Shiriaeva A, Olsen RHJ, Tribo AR, Yous S, Stevens RC, Weierstall U, Katritch V, Roth BL, Liu W & Cherezov V (2019) Structural basis of ligand recognition at the human MT1 melatonin receptor. Nature 569, 284–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang C, Jiang Y, Ma J, Wu H, Wacker D, Katritch V, Han GW, Liu W, Huang XP, Vardy E, McCorvy JD, Gao X, Zhou XE, Melcher K, Zhang C, Bai F, Yang H, Yang L, Jiang H, Roth BL, Cherezov V, Stevens RC & Xu HE (2013) Structural basis for molecular recognition at serotonin receptors. Science 340, 610–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wacker D, Wang C, Katritch V, Han GW, Huang XP, Vardy E, McCorvy JD, Jiang Y, Chu M, Siu FY, Liu W, Xu HE, Cherezov V, Roth BL & Stevens RC (2013) Structural features for functional selectivity at serotonin receptors. Science 340, 615–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng Y, McCorvy JD, Harpsoe K, Lansu K, Yuan S, Popov P, Qu L, Pu M, Che T, Nikolajsen LF, Huang XP, Wu Y, Shen L, Bjorn-Yoshimoto WE, Ding K, Wacker D, Han GW, Cheng J, Katritch V, Jensen AA, Hanson MA, Zhao S, Gloriam DE, Roth BL, Stevens RC & Liu ZJ (2018) 5-HT2C Receptor Structures Reveal the Structural Basis of GPCR Polypharmacology. Cell 172, 719–730.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kimura KT, Asada H, Inoue A, Kadji FMN, Im D, Mori C, Arakawa T, Hirata K, Nomura Y, Nomura N, Aoki J, Iwata S & Shimamura T (2019) Structures of the 5-HT2A receptor in complex with the antipsychotics risperidone and zotepine. Nat Struct Mol Biol 26, 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johansson LC, Stauch B, McCorvy JD, Han GW, Patel N, Huang XP, Batyuk A, Gati C, Slocum ST, Li C, Grandner JM, Hao S, Olsen RHJ, Tribo AR, Zaare S, Zhu L, Zatsepin NA, Weierstall U, Yous S, Stevens RC, Liu W, Roth BL, Katritch V & Cherezov V (2019) XFEL structures of the human MT2 melatonin receptor reveal the basis of subtype selectivity. Nature 569, 289–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stauch B, Johansson L, Ishchenko A, Han GW, Batyuk A & Cherezov V (2018) Advances in Structure Determination of G Protein-Coupled Receptors by SFX in X-ray Free Electron Lasers: A Revolution in Structural Biology (Boutet S, Fromme P & Hunter MS, eds) pp. 301–329, Springer International Publishing, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cherezov V (2011) Lipidic cubic phase technologies for membrane protein structural studies. Curr Opin Struct Biol 21, 559–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chun E, Thompson AA, Liu W, Roth CB, Griffith MT, Katritch V, Kunken J, Xu F, Cherezov V, Hanson MA & Stevens RC (2012) Fusion partner toolchest for the stabilization and crystallization of G protein-coupled receptors. Structure 20, 967–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heydenreich FM, Vuckovic Z, Matkovic M & Veprintsev DB (2015) Stabilization of G protein-coupled receptors by point mutations. Front Pharmacol 6, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alexandrov AI, Mileni M, Chien EY, Hanson MA & Stevens RC (2008) Microscale fluorescent thermal stability assay for membrane proteins. Structure 16, 351–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cherezov V, Liu J, Griffith M, Hanson MA & Stevens RC (2008) LCP-FRAP Assay for Pre-Screening Membrane Proteins for in Meso Crystallization. Cryst Growth Des 8, 4307–4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin J, Mobarec JC, Kolb P & Rosenbaum DM (2015) Crystal structure of the human OX2 orexin receptor bound to the insomnia drug suvorexant. Nature 519, 247–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stauch B & Cherezov V (2018) Serial Femtosecond Crystallography of G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Ann Rev Biophys 47, 377–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boutet S, Lomb L, Williams GJ, Barends TR, Aquila A, Doak RB, Weierstall U, DePonte DP, Steinbrener J, Shoeman RL, Messerschmidt M, Barty A, White TA, Kassemeyer S, Kirian RA, Seibert MM, Montanez PA, Kenney C, Herbst R, Hart P, Pines J, Haller G, Gruner SM, Philipp HT, Tate MW, Hromalik M, Koerner LJ, van Bakel N, Morse J, Ghonsalves W, Arnlund D, Bogan MJ, Caleman C, Fromme R, Hampton CY, Hunter MS, Johansson LC, Katona G, Kupitz C, Liang M, Martin AV, Nass K, Redecke L, Stellato F, Timneanu N, Wang D, Zatsepin NA, Schafer D, Defever J, Neutze R, Fromme P, Spence JC, Chapman HN & Schlichting I (2012) High-resolution protein structure determination by serial femtosecond crystallography. Science 337, 362–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weierstall U, James D, Wang C, White TA, Wang D, Liu W, Spence JC, Bruce Doak R, Nelson G, Fromme P, Fromme R, Grotjohann I, Kupitz C, Zatsepin NA, Liu H, Basu S, Wacker D, Han GW, Katritch V, Boutet S, Messerschmidt M, Williams GJ, Koglin JE, Marvin Seibert M, Klinker M, Gati C, Shoeman RL, Barty A, Chapman HN, Kirian RA, Beyerlein KR, Stevens RC, Li D, Shah ST, Howe N, Caffrey M & Cherezov V (2014) Lipidic cubic phase injector facilitates membrane protein serial femtosecond crystallography. Nat Commun 5, 3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu W, Wacker D, Gati C, Han GW, James D, Wang D, Nelson G, Weierstall U, Katritch V, Barty A, Zatsepin NA, Li D, Messerschmidt M, Boutet S, Williams GJ, Koglin JE, Seibert MM, Wang C, Shah ST, Basu S, Fromme R, Kupitz C, Rendek KN, Grotjohann I, Fromme P, Kirian RA, Beyerlein KR, White TA, Chapman HN, Caffrey M, Spence JC, Stevens RC & Cherezov V (2013) Serial femtosecond crystallography of G protein-coupled receptors. Science 342, 1521–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Audet M, White KL, Breton B, Zarzycka B, Han GW, Lu Y, Gati C, Batyuk A, Popov P, Velasquez J, Manahan D, Hu H, Weierstall U, Liu W, Shui W, Katritch V, Cherezov V, Hanson MA & Stevens RC (2019) Crystal structure of misoprostol bound to the labor inducer prostaglandin E2 receptor. Nat Chem Biol 15, 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luginina A, Gusach A, Marin E, A. M, Brouillette R, Popov P, Shiriaeva A, Besserer-Offroy É, Longpré JM, Lyapina E, Ishchenko A, Patel N, Polovinkin V, Safronova N, Bogorodskiy A, Edelweiss E, Hu H, Weierstall U, Liu W, Batyuk A, Gordeliy V, Han GW, Sarret P, Katritch V, Borshchevskiy V & Cherezov V (2019) Structure-Based Mechanism of Cysteinyl Leukotriene Receptor Inhibition by Antiasthmatic Drugs. Sci Adv 5, eaax2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boutet S & Williams GJ (2010) The Coherent X-ray Imaging (CXI) instrument at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). New J Phys 12, 035024. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ishchenko A, Stauch B, Han GW, Batyuk A, Shiriaeva A, Li C, Zatsepin N, Weierstall U, Liu W, Nango E, Nakane T, Tanaka R, Tono K, Joti Y, Iwata S, Moraes I, Gati C & Cherezov V (2019) Toward G protein-coupled receptor structure-based drug design using X-ray lasers, IUCrJ. 6, 1106–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.White TA, Mariani V, Brehm W, Yefanov O, Barty A, Beyerlein KR, Chervinskii F, Galli L, Gati C, Nakane T, Tolstikova A, Yamashita K, Yoon CH, Diederichs K & Chapman HN (2016) Recent developments in CrystFEL. J Appl Crystallogr 49, 680–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barty A, Kirian RA, Maia FR, Hantke M, Yoon CH, White TA & Chapman H (2014) Cheetah: software for high-throughput reduction and analysis of serial femtosecond X-ray diffraction data. J Appl Crystallogr 47, 1118–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Warne T, Edwards PC, Dore AS, Leslie AGW & Tate CG (2019) Molecular basis for high-affinity agonist binding in GPCRs. Science 364, 775–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Audet M & Stevens RC (2019) Emerging structural biology of lipid G protein-coupled receptors. Protein Sci 28, 292–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chrencik JE, Roth CB, Terakado M, Kurata H, Omi R, Kihara Y, Warshaviak D, Nakade S, Asmar-Rovira G, Mileni M, Mizuno H, Griffith MT, Rodgers C, Han GW, Velasquez J, Chun J, Stevens RC & Hanson MA (2015) Crystal Structure of Antagonist Bound Human Lysophosphatidic Acid Receptor 1. Cell 161, 1633–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanson MA, Roth CB, Jo E, Griffith MT, Scott FL, Reinhart G, Desale H, Clemons B, Cahalan SM, Schuerer SC, Sanna MG, Han GW, Kuhn P, Rosen H & Stevens RC (2012) Crystal structure of a lipid G protein-coupled receptor. Science 335, 851–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hua T, Vemuri K, Nikas SP, Laprairie RB, Wu Y, Qu L, Pu M, Korde A, Jiang S, Ho JH, Han GW, Ding K, Li X, Liu H, Hanson MA, Zhao S, Bohn LM, Makriyannis A, Stevens RC & Liu ZJ (2017) Crystal structures of agonist-bound human cannabinoid receptor CB1. Nature 547, 468–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 66.Li X, Hua T, Vemuri K, Ho JH, Wu Y, Wu L, Popov P, Benchama O, Zvonok N, Locke K, Qu L, Han GW, Iyer MR, Cinar R, Coffey NJ, Wang J, Wu M, Katritch V, Zhao S, Kunos G, Bohn LM, Makriyannis A, Stevens RC & Liu ZJ (2019) Crystal Structure of the Human Cannabinoid Receptor CB2. Cell 176, 459–467.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toyoda Y, Morimoto K, Suno R, Horita S, Yamashita K, Hirata K, Sekiguchi Y, Yasuda S, Shiroishi M, Shimizu T, Urushibata Y, Kajiwara Y, Inazumi T, Hotta Y, Asada H, Nakane T, Shiimura Y, Nakagita T, Tsuge K, Yoshida S, Kuribara T, Hosoya T, Sugimoto Y, Nomura N, Sato M, Hirokawa T, Kinoshita M, Murata T, Takayama K, Yamamoto M, Narumiya S, Iwata S & Kobayashi T (2019) Ligand binding to human prostaglandin E receptor EP4 at the lipid-bilayer interface. Nat Chem Biol 15, 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Okada T, Sugihara M, Bondar AN, Elstner M, Entel P & Buss V (2004) The retinal conformation and its environment in rhodopsin in light of a new 2.2 A crystal structure. J Mol Biol 342, 571–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ivanov AA, Voronkov AE, Baskin II, Palyulin VA & Zefirov NS (2004) The study of the mechanism of binding of human ML1A melatonin receptor ligands using molecular modeling. Dokl Biochem Biophys 394, 49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Farce A, Chugunov AO, Loge C, Sabaouni A, Yous S, Dilly S, Renault N, Vergoten G, Efremov RG, Lesieur D & Chavatte P (2008) Homology modeling of MT1 and MT2 receptors. Eur J Med Chem 43, 1926–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Clement N, Renault N, Guillaume JL, Cecon E, Journe AS, Laurent X, Tadagaki K, Coge F, Gohier A, Delagrange P, Chavatte P & Jockers R (2017) Importance of the second extracellular loop for melatonin MT1 receptor function and absence of melatonin binding in GPR50. Br J Pharmacol 175, 3281–3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kokkola T, Foord SM, Watson MA, Vakkuri O & Laitinen JT (2003) Important amino acids for the function of the human MT1 melatonin receptor. Biochem Pharmacol 65, 1463–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gerdin MJ, Mseeh F & Dubocovich ML (2003) Mutagenesis studies of the human MT2 melatonin receptor. Biochem Pharmacol 66, 315–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pala D, Lodola A, Bedini A, Spadoni G & Rivara S (2013) Homology models of melatonin receptors: challenges and recent advances. Int J Mol Sci 14, 8093–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zlotos DP, Jockers R, Cecon E, Rivara S & Witt-Enderby PA (2014) MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors: ligands, models, oligomers, and therapeutic potential. J Med Chem 57, 3161–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rivara S, Mor M, Bedini A, Spadoni G & Tarzia G (2008) Melatonin Receptor Agonists: SAR and Applications to the Treatment of Sleep-Wake Disorders. Curr Top Med Chem 8, 954–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Descamps-Francois C, Yous S, Chavatte P, Audinot V, Bonnaud A, Boutin JA, Delagrange P, Bennejean C, Renard P & Lesieur D (2003) Design and synthesis of naphthalenic dimers as selective MT1 melatoninergic ligands. J Med Chem 46, 1127–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dijkman PM, Castell OK, Goddard AD, Munoz-Garcia JC, de Graaf C, Wallace MI & Watts A (2018) Dynamic tuneable G protein-coupled receptor monomer-dimer populations. Nat Commun 9, 1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vaidehi N, Grisshammer R & Tate CG (2016) How Can Mutations Thermostabilize G-Protein-Coupled Receptors? Trends Pharmacol Sci 37, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jockers R, Maurice P, Boutin JA & Delagrange P (2008) Melatonin receptors, heterodimerization, signal transduction and binding sites: what’s new? Br J Pharmacol 154, 1182–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Karamitri A, Sadek MS, Journe AS, Gbahou F, Gerbier R, Osman MB, Habib SAM, Jockers R & Zlotos DP (2019) O-linked melatonin dimers as bivalent ligands targeting dimeric melatonin receptors. Bioorg Chem 85, 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ferre S, Casado V, Devi LA, Filizola M, Jockers R, Lohse MJ, Milligan G, Pin JP & Guitart X (2014) G protein-coupled receptor oligomerization revisited: functional and pharmacological perspectives. Pharmacol Rev 66, 413–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baba K, Benleulmi-Chaachoua A, Journe AS, Kamal M, Guillaume JL, Dussaud S, Gbahou F, Yettou K, Liu C, Contreras-Alcantara S, Jockers R & Tosini G (2013) Heteromeric MT1/MT2 melatonin receptors modulate photoreceptor function. Sci Signal 6, ra89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dufourny L, Levasseur A, Migaud M, Callebaut I, Pontarotti P, Malpaux B & Monget P (2008) GPR50 is the mammalian ortholog of Mel1c: evidence of rapid evolution in mammals. BMC Evol Biol 8, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kang Y, Zhou XE, Gao X, He Y, Liu W, Ishchenko A, Barty A, White TA, Yefanov O, Han GW, Xu Q, de Waal PW, Ke J, Tan MH, Zhang C, Moeller A, West GM, Pascal BD, Van Eps N, Caro LN, Vishnivetskiy SA, Lee RJ, Suino-Powell KM, Gu X, Pal K, Ma J, Zhi X, Boutet S, Williams GJ, Messerschmidt M, Gati C, Zatsepin NA, Wang D, James D, Basu S, Roy-Chowdhury S, Conrad CE, Coe J, Liu H, Lisova S, Kupitz C, Grotjohann I, Fromme R, Jiang Y, Tan M, Yang H, Li J, Wang M, Zheng Z, Li D, Howe N, Zhao Y, Standfuss J, Diederichs K, Dong Y, Potter CS, Carragher B, Caffrey M, Jiang H, Chapman HN, Spence JC, Fromme P, Weierstall U, Ernst OP, Katritch V, Gurevich VV, Griffin PR, Hubbell WL, Stevens RC, Cherezov V, Melcher K & Xu HE (2015) Crystal structure of rhodopsin bound to arrestin by femtosecond X-ray laser. Nature 523, 561–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ishchenko A, Gati C & Cherezov V (2018) Structural biology of G protein-coupled receptors: new opportunities from XFELs and cryoEM. Curr Opin Struct Biol 51, 44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kamal M, Gbahou F, Guillaume JL, Daulat AM, Benleulmi-Chaachoua A, Luka M, Chen P, Kalbasi Anaraki D, Baroncini M, Mannoury la Cour C, Millan MJ, Prevot V, Delagrange P & Jockers R (2015) Convergence of melatonin and serotonin (5-HT) signaling at MT2/5-HT2C receptor heteromers. J Biol Chem 290, 11537–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]