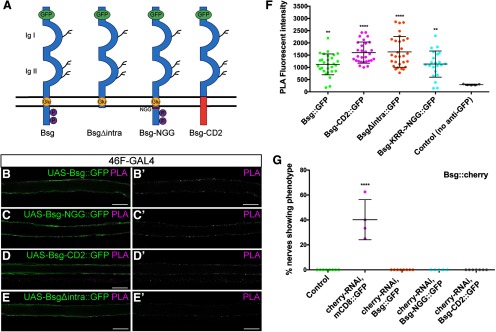

Figure 8.

The extracellular domain of Bsg is sufficient for close proximity to integrins. A, Control and mutant Bsg constructs used in rescue experiments. Each transgene is labeled with extracellular GFP. Adapted with permission from Besse et al. (2007). B-D, PLAs testing the association of the different Bsg transgenes and the βPS integrin (mys) subunit using the perineurial glial 46F-GAL4 driver. Scale bars, 15 μm. Positive PLA (magenta) was observed between Bsg::GFP and integrin in nerves expressing: UAS-Bsg::GFP (B); UAS-Bsg-NGG::GFP where conserved transmembrane residues KRR have been mutated to NGG (C); UAS-Bsg-CD2::GFP where the transmembrane and intracellular domains of Bsg have been replaced by those of rat CD2 (D); and UAS-BsgΔintra::GFP construct where Bsg is lacking its intracellular domain (E). F, Fluorescence of PLA reactions in all UAS-Bsg::GFP constructs was significantly higher than in control lacking anti-GFP antibody, indicating that mutations to transmembrane and intracellular domains of Bsg do not affect the Bsg-integrin interaction in the perineurial glia (**p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001). G, Rescue of the Bsg knockdown phenotype using Bsg constructs. Knockdown of Bsg::cherry in the perineurial glia using 46F-GAL4 driving expression of cherry-RNAi and UAS-mCD8::GFP resulted in glial compression in 40.2% of nerves. This phenotype was completely rescued by coexpression of normal and mutant UAS-Bsg::GFP constructs (****p < 0.0001). **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.