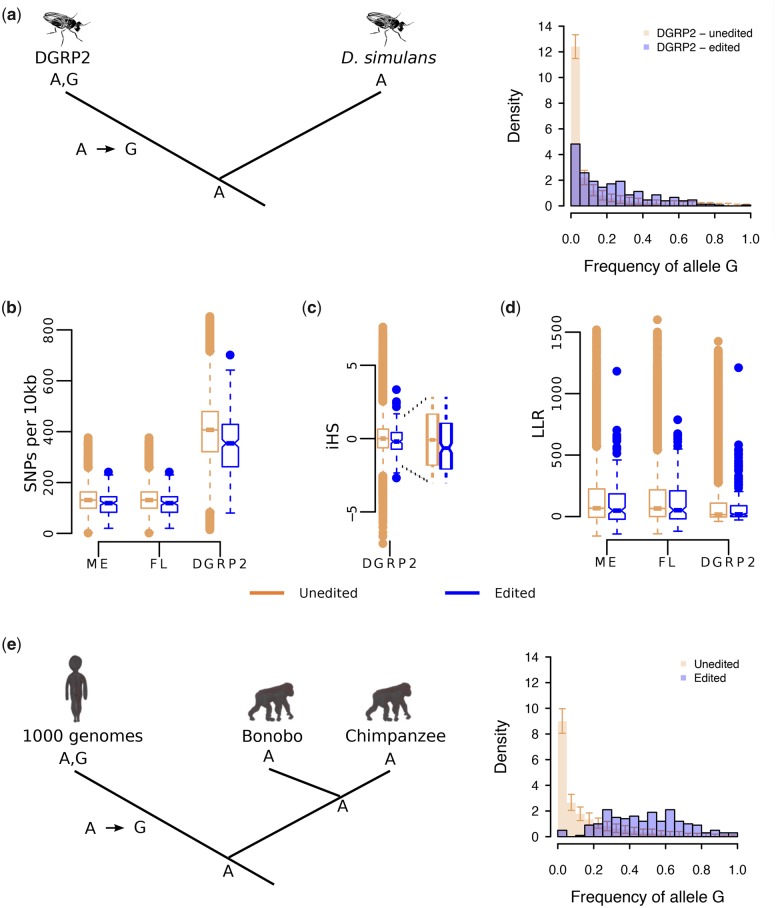

Fig. 1.—

Properties of the G alleles segregating at edited sites in Drosophila melanogaster and human. (a) We used D. simulans as an outgroup to infer the ancestral state of the A, G polymorphisms in D. melanogaster. The right panel shows the average frequency spectrum and 95% confidence interval of the derived G alleles at unedited sites (peach) and the frequency spectrum for the derived G alleles at edited sites (blue). The shift of the blue distribution toward higher G allele frequencies is a signal of positive selection for the derived G alleles at edited sites. The frequency shows an average increase of 0.12. (b) Windows centered on polarized A-to-G mutations have lower diversity (in SNPs per 10 kb) for edited SNPs than for unedited SNPs (P < 10−4 for each paired comparison; one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test). (c) At polarized edited sites, the extended homozygosity of the haplotype carrying the derived G allele is longer than that of the haplotypes carrying the ancestral A allele (average iHS score < 0). At unedited sites, the extended homozygosity is similar for both haplotypes (average iHS score ∼ 0). P = 0.004, one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test for the null hypothesis iHS (edited) ≥ iHS (unedited). (d) The LLR comparing a long-term balancing selection model versus a neutral model tend to be lower for edited sites than for unedited sites (expected to be higher if balancing selection were more prominent for edited sites). P ≫ 0.05 for each paired comparison; two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test. (e) We used Bonobo and Chimpanzee as an outgroup to infer the ancestral state of the genic A, G polymorphisms in the human genome. The right panel shows that G alleles segregate at higher frequencies in edited sites (blue) than in unedited sites (peach). The frequency shows an average increase of 0.34.