Abstract

Background

Although rituximab-based high-dose therapy is frequently used in DLBCL patients undergoing autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (auto-HCT), data supporting the benefit are not available. Herein, we report the impact of rituximab-based conditioning on auto-HCT outcomes in DLBCL.

Methods

Using the CIBMTR registry, 862 adult DLBCL patients undergoing auto-HCT between 2003–2017 using BEAM (BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) conditioning regimen were included. All patients received frontline rituximab (R)-containing chemoimmunotherapy and had chemosensitive disease pre-HCT. Early chemoimmunotherapy failure (ECitF) was defined as not achieving a complete remission (CR) post-frontline chemoimmunotherapy, or relapse within 1-year of initial diagnosis. Primary outcome was overall survival (OS).

Results

The study cohort was divided into 2 groups; BEAM (n=667) and R-BEAM (n=195). On multivariate analysis, no significant difference was seen in OS (P=0.83) or progression-free survival (PFS) (P=0.61) across the two cohorts. No significant association between the use of rituximab and risk of relapse (P=0.15) or non-relapse mortality (P=0.12) was observed. Variables independently associated with lower OS included older age at auto-HCT (P<0.001), absence of CR at auto-HCT (P<0.001) and ECitF (P<0.001). Older age (P<0.0002) and non-CR pre-HCT (P<0.0001) were also associated with inferior PFS. There was no significant difference in early infectious complications between the two cohorts.

Conclusion

In this large registry analysis of DLBCL patients undergoing auto-HCT, the addition of rituximab to the BEAM conditioning regimen had no impact on transplantation outcomes. Older age, absence of CR pre auto-HCT and ECitF were associated with inferior survival.

Keywords: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, autologous transplantation, rituximab, BEAM, chemoimmunotherapy

Condensed Abstract

Using CIBMTR registry data, we demonstrate that in DLBCL patients undergoing auto-HCT, the addition of rituximab to the BEAM conditioning regimen had no impact on survival outcomes after transplantation.

Introduction

Rituximab has revolutionized the treatment landscape of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL). Integrating rituximab into upfront and subsequent lines of treatment has improved response rates, progression-free and overall survival (OS) in B-cell NHL1–4. In randomized clinical trials, the addition of rituximab to CHOP (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine and prednisone) chemotherapy resulted in superior complete response (CR) rate, event-free survival (EFS) and OS compared to CHOP in both young (18–60 years) and elderly (60–80 years) patients with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)1, 5.

The benefit of combining rituximab with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (auto-HCT) conditioning regimens is not well defined and no randomized clinical trials have explored this issue. Retrospective studies evaluating the integration of rituximab with conditioning regimens for auto-HCT in B-cell NHL have produced conflicting results6–8. Flohr et al. reported encouraging response rates when rituximab was administered on days −10 and −3 with various conditioning regimens for auto-HCT6. Unfortunately, in this study there was no non-rituximab control arm and multiple B-cell NHL histologies were included. The BMT CTN 0410 phase III trial found comparable outcomes between rituximab + BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan) and B-BEAM (iodine I-131 tositumomab + BEAM) in relapsed chemosensitive DLBCL7. As there was no BEAM-alone arm, the study does not explicitly address whether rituximab-BEAM (R-BEAM) offered any benefit over BEAM.

No studies evaluating the benefit of combining rituximab with BEAM conditioning regimen in patients with DLBCL have been reported to our knowledge. As efforts to reduce health care cost are mounting, it is imperative to determine if addition of an anti CD20 monoclonal antibody could produce improved outcomes in DLBCL post auto transplantation. This is more relevant in the modern-era, as rituximab containing regimens are standard-of-care in both upfront and salvage setting and the benefit of brief exposure to rituximab (in a largely rituximab exposed patient population) during auto-HCT conditioning remains to be proven. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective study using the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) registry comparing the post auto-HCT outcomes between R-BEAM and BEAM in patients with DLBCL.

Methods

Data source

The CIBMTR is a collaborative research program managed by Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) and The National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) that collects data from more than 500-transplant centers worldwide. Participating sites are required to report detailed data on both autologous and allogeneic HCT with frequent updates gathered during the longitudinal follow-up of transplant patients and the compliance is monitored by on-site audits. Computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians’ review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers ensure data quality. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. The MCW and NMDP institutional review boards approved this study.

Patients

DLBCL patients age ≥18 years, who received an auto-HCT between 2003–2017 and reported to CIBMTR were included in this analysis. Conditioning for auto-HCT was limited to BEAM regimen, as rituximab was infrequently used with non-BEAM conditioning approaches. All patients received rituximab-containing chemoimmunotherapy in the first-line setting and had chemosensitive disease prior to auto-HCT. Patients who received a bone marrow graft (n= 36), underwent non-rituximab containing frontline therapy (n=134) and those with active central nervous system involvement prior to auto-HCT (n= 5) were excluded.

Definitions and Endpoints:

Chemosensitive disease is defined as achieving either a CR or partial remission (PR) to treatment prior to transplant. Response to frontline chemoimmunotherapy and disease status prior to auto-HCT were determined using the International Working Group criteria8,9. Early chemoimmunotherapy failure was defined as not achieving a CR after first line of chemoimmunotherapy or relapse/progression within 1 year of initial diagnosis as previously reported10,11.

Primary endpoint was OS. Death from any cause was considered an event and surviving patients were censored at last follow-up. Secondary outcomes included NRM, relapse/progression, and progression-free survival (PFS). NRM was defined as death without evidence of prior lymphoma progression/relapse; relapse was considered a competing risk. Relapse/progression was defined as progressive lymphoma after auto-HCT or lymphoma recurrence after a CR; NRM was considered a competing risk. For PFS, a patient was considered a treatment failure at the time of progression/relapse or death from any cause. Patients alive without evidence of disease relapse or progression were censored at last follow-up. Neutrophil engraftment is time to achieve an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) >0.5 ×109/L that is sustained for three consecutive days post-transplant. Platelet engraftment is time to achieve a platelet count of >20 × 109/L post transplant without any platelet transfusions for 7 consecutive days. Death prior to engraftment was considered a competing risk. All outcomes will be calculated relative to the transplant date.

Statistical Analysis:

All the endpoints were compared between R-BEAM and BEAM cohorts. Patient-, disease- and transplant-related variables were compared between the two cohorts using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon two-sample test for continuous variables. The distribution of OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cumulative incidence method was used to estimate hematopoietic recovery, NRM, relapse/progression while accounting for competing events. Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to identify prognostic factors for relapse, NRM, PFS, and OS using forward stepwise variable selection. No covariates violated the proportional hazards assumption. No significant interactions between the main effect and significant covariates were found. No center effect was found based on the score test of homogeneity12. Results were reported as hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence interval (CI) for HR and p-value. Covariates with a p value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The variables considered in multivariate analysis are shown in Table 1S of supplemental appendix. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results:

Baseline Characteristics

The study population (n=862) was divided into 2 cohorts; BEAM (n=667) and R-BEAM (n=195). The baseline characteristics between the 2 groups were comparable (Table 1), with respect to patient age, gender, performance score, number of prior therapy lines, early chemoimmunotherapy failure and remission status prior to auto-HCT. Significantly more R-BEAM cohort patients had exposure to rituximab immediately before auto-HCT, either as part of last chemotherapy line before HCT or received rituximab with pre-transplant mobilization regiment (N=168; 86%) compared to the BEAM cohort subjects with similar pre-HCT rituximab exposure (n=504; 76%). The median follow up of survivors was 48 (range 1–171) months and 64 (range 3–142) months in the BEAM and the R-BEAM groups respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients receiving BEAM (with or without rituximab) conditioning regimen and autologous HCT for DLBCL during 2003–2017

| BEAM | R-BEAM | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 667 | 195 | |

| Number of centers | 93 | 35 | |

| Median patient age, years (range) | 61 (18–80) | 60 (20–77) | 0.83 |

| ≥ 65 years | 218 (33) | 60 (31) | |

| Male sex | 393 (59) | 115 (59) | 0.99 |

| Patient race1 | 0.38 | ||

| Caucasian | 520 (78) | 159 (82) | |

| African American | 82 (12) | 22 (11) | |

| Asian | 44 (7) | 6 (3) | |

| Other | 7 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Missing | 14 (2) | 6 (3) | |

| Karnofsky Performance Score ≥ 90 | 368 (55) | 100 (51) | 0.39 |

| Missing | 17 (3) | 8 (4) | |

| Stage III-IV at diagnosis | 155 (23) | 44 (23) | 0.65 |

| Missing | 61 (9) | 14 (7) | |

| LDH elevated at diagnosis | 89 (13) | 27 (14) | 0.98 |

| Missing | 398 (60) | 115 (59) | |

| Median number of lines of therapy prior to HCT | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–5) | 0.26 |

| 1–2 lines | 440 (66) | 137 (70) | |

| 3–5 lines | 227 (34) | 58 (30) | |

| No bone marrow involvement at diagnosis | 474 (71) | 149 (76) | 0.26 |

| Missing | 57 (9) | 11 (6) | |

| CNS involved at diagnosis | 5 (<1) | 3 (2) | 0.59 |

| Extranodal involvement at diagnosis | 393 (59) | 118 (61) | 0.42 |

| Missing | 57 (9) | 11 (6) | |

| Median Time from diagnosis to HCT (range) | 17 (2–313) | 17 (3–140) | 0.32 |

| Early chemoimmunotherapy failure2 | 0.48 | ||

| No | 313 (47) | 84 (43) | |

| Yes | 343 (51) | 109 (56) | |

| Missing | 11 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| Remission status | 0.07 | ||

| Complete remission | 418 (63) | 108 (55) | |

| Partial remission | 249 (37) | 87 (45) | |

| Primary refractory after first line of therapy | 0.85 | ||

| No | 402 (60) | 121 (62) | |

| Yes | 236 (35) | 67 (34) | |

| Missing | 29 (4) | 7 (4) | |

| Rituximab given with last therapy line prior to HCT and/or with mobilization | 504 (76) | 168 (86) | 0.002 |

| Median follow-up of survivors (range), months | 48 (1–171) | 64 (3–142) | |

Patient race -other: BEAM: 2 Pacific Islander; 5 Native American. R-BEAM: 2 Native American.

Early therapy failure defined as not achieving CR after first line R+chemo, or relapse/progression within 1-year of DLBCL diagnosis.

Abbreviations: BEAM: - carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan; R-BEAM: rituximab +BEAM; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; HCT: hematopoietic cell transplantation; CNS: central nervous system; DLBCL: diffuse large B cell lymphoma

Hematopoietic Recovery and Infectious Complications

The cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery at day 30 was comparable between both groups 99% (95%CI=98–100%) and 98% (95%CI=96–100%) in the BEAM and the R-BEAM, respectively (Table 2). No difference was observed in the platelet recovery during the first 100 days: 97% (95%CI=96–98%) in the BEAM and 97% (95%CI=94–99%) in the R-BEAM respectively. In comparison to BEAM, addition of rituximab did not increase the risk of bacterial, viral or fungal infections during the first 100-day after auto-HCT (for details see Supplement Materials Table S2).

Table 2.

Univariate outcomes of patients receiving BEAM conditioning regimen and autologous HCT for DLBCL during 2003–2017

| BEAM (N = 667) | R-BEAM (N = 195) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | p-value |

| Neutrophil recovery | 665 | 193 | 0.18 | ||

| 30-day | 99 (98–100)% | 98 (96–100)% | 0.50 | ||

| Platelet recovery | 663 | 192 | 0.72 | ||

| 100-day | 97 (96–98)% | 97 (94–99)% | 0.91 | ||

| Non-relapse mortality | 667 | 195 | 0.12 | ||

| 1-year | 5 (3–6)% | 6 (3–10)% | 0.44 | ||

| 4-year | 9 (7–11)% | 11 (7–16)% | 0.39 | ||

| Relapse/progression | 667 | 195 | 0.25 | ||

| 1-year | 31 (28–35)% | 28 (22–35)% | 0.41 | ||

| 4-year | 44 (40–48)% | 41 (33–48)% | 0.40 | ||

| Progression-free survival | 667 | 195 | 0.75 | ||

| 1-year | 64 (60–68)% | 65 (59–72)% | 0.69 | ||

| 4-year | 47 (43–51)% | 48 (41–56)% | 0.77 | ||

| Overall survival | 667 | 195 | 0.77 | ||

| 1-year | 78 (74–81)% | 81 (75–86)% | 0.33 | ||

| 4-year | 61 (57–65)% | 58 (51–65)% | 0.54 | ||

Abbreviations: BEAM: carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan; R-BEAM: rituximab +BEAM; N Eval: number evaluated; Prob: probability; HCT: hematopoietic cell transplantation; DLBCL: diffuse large B cell lymphoma

Non-relapse Mortality and Relapse/Progression

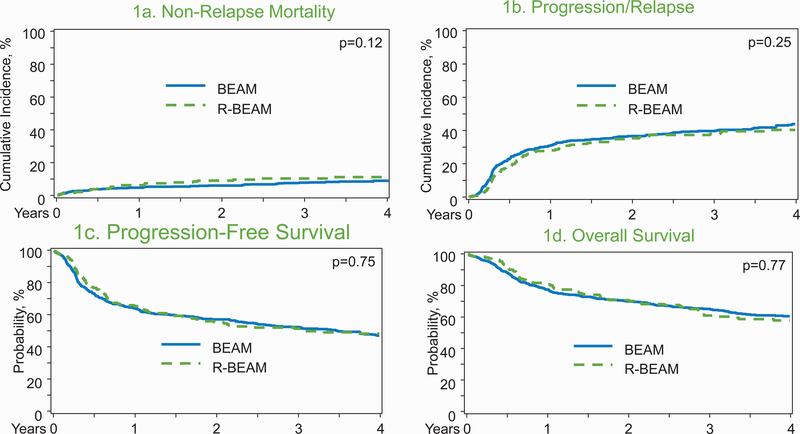

On univariate analysis, there was no significant difference in the 1-year cumulative incidence of NRM in the BEAM 5% (95%CI 3–6%) versus R-BEAM 6% (95%CI 3–10%) groups (p=0.44; Table 2; Figure 1A). On multivariate analysis (MVA), age; ≥65 years was associated with a higher NRM risk (HR: 6.72; 95%CI=1.63–27.78; p=0.01) (Table 3). The NRM risk was not significantly different between the BEAM and R-BEAM cohorts (HR: 1.43; 95%CI=0.91–2.26; p=0.12).

Figure 1:

Transplant outcomes in BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan) and R-BEAM (rituximab +BEAM) group. (A) Non relapse mortality in BEAM and R-BEAM cohort. (B) Progression/relapse in the BEAM and R-BEAM cohort. (C) Progression free survival in the BEAM and R-BEAM cohort. (D) Overall survival in the in the BEAM and R-BEAM cohort.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis

| N | HR | 95% CI Lower Limit | 95% CI Upper Limit | Overall p-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse | ||||||

| Rituximab use in conditioning | ||||||

| BEAM | 667 | 1 | 0.15 | |||

| R-BEAM | 195 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 1.07 | 0.15 | |

| Remission status | ||||||

| Complete remission | 526 | 1 | <.0001 | |||

| Partial remission | 336 | 1.81 | 1.47 | 2.23 | <.0001 | |

| Non-relapse mortality (NRM) | ||||||

| Rituximab use in conditioning | ||||||

| BEAM | 667 | 1 | 0.12 | |||

| R-BEAM | 195 | 1.43 | 0.909 | 2.26 | 0.12 | |

| Age Group | ||||||

| 18–39 | 72 | 1 | 0.001 | |||

| 40–49 | 113 | 2 | 0.40 | 9.92 | 0.40 | |

| 50–59 | 229 | 3.25 | 0.76 | 13.89 | 0.11 | |

| 60–64 | 170 | 3.98 | 0.92 | 17.16 | 0.06 | |

| ≥65 | 278 | 6.72 | 1.63 | 27.78 | 0.01 | |

| Progress-free survival (PFS) | ||||||

| Rituximab use in conditioning | ||||||

| BEAM | 667 | 1 | 0.61 | |||

| R-BEAM | 195 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 1.18 | 0.61 | |

| Age Group | ||||||

| 18–39 | 72 | 1 | 0.0002 | |||

| 40–49 | 113 | 1.42 | 0.87 | 2.30 | 0.16 | |

| 50–59 | 229 | 1.6 | 1.04 | 2.49 | 0.03 | |

| 60–64 | 170 | 1.70 | 1.09 | 2.65 | 0.02 | |

| ≥65 | 278 | 2.26 | 1.48 | 3.45 | 0.0002 | |

| Remission status | ||||||

| Complete remission | 526 | 1 | <.0001 | |||

| Partial remission | 336 | 1.78 | 1.47 | 2.14 | <.0001 | |

| Overall Survival (OS) | ||||||

| Rituximab use in conditioning | ||||||

| BEAM | 667 | 1 | 0.83 | |||

| R-BEAM | 195 | 1.03 | 0.81 | 1.31 | 0.83 | |

| Age Group | ||||||

| 18–39 | 72 | 1 | <.0001 | |||

| 40–49 | 113 | 1.30 | 0.71 | 2.38 | 0.40 | |

| 50–59 | 229 | 2.09 | 1.23 | 3.57 | 0.007 | |

| 60–64 | 170 | 2.19 | 1.27 | 3.78 | 0.005 | |

| ≥65 | 278 | 3.05 | 1.81 | 5.13 | <.0001 | |

| Remission status | ||||||

| Complete remission | 526 | 1 | <.0001 | |||

| Partial remission | 336 | 1.67 | 1.39 | 2.07 | <.0001 | |

|

Early chemoimmunotherapy failure |

||||||

| No | 397 | 1 | 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 452 | 1.52 | 1.22 | 1.91 | 0.0002 | |

| Missing | 13 | 1.32 | 0.54 | 3.26 | 0.54 |

Abbreviations: BEAM: carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan; R-BEAM: rituximab +BEAM; HR: hazard ratio; CI=: confidence interval; N: number of patients

The 4-year cumulative incidence of relapse/progression was 44% (95%CI=40–48%) in the BEAM and 41% (95%CI=33–48%) in the R-BEAM cohort (p=0.40; Table 2, Figure 1B). On MVA, R-BEAM did not significantly reduce the risk of relapse (HR: 0.83; 95%CI=0.65–1.07; p=0.15) (Table 3). Relative to patients in CR, patients in PR prior to transplant were at significantly higher risk of relapse/progression (HR1.81; 95%CI=1.47–2.23; p=<0.0001).

Progression-free and Overall Survival

The 4-year PFS was 47% (95%CI=43–51%) in the BEAM cohort compared to 48% (95%CI=41–56%) in the R-BEAM group (p=0.77; Table 2, Figure 1C). On MVA, R-BEAM regimen was not associated with a significantly improved PFS (HR=0.94; 95%CI=0.76–1.18; p=0.61). Variables independently predictive of PFS are shown in Table 3.

The 4-year OS was 61% (95%CI=57–65%) in the BEAM cohort compared to 58% (95%CI=51–65%) in the R-BEAM group (p=0.77; Table 2, Figure 1D). On MVA, R-BEAM did not reduce mortality risk relative to BEAM conditioning (HR=1.03; 95%CI=0.81–1.31; p=0.83). On MVA, irrespective of the conditioning approach, older age (≥50years), PR before auto-HCT and history of early chemoimmunotherapy failure were independently associated with higher mortality risk after auto-HCT (Table 3).

Impact of Rituximab Dose

In patients who received R-BEAM in conditioning, the median rituximab dose during conditioning was 375mg/m2 (range: 375–2012 mg/m2). One hundred and eight patients received a dose of 375mg/m2; while 85 patients received a dose of >375mg/m2; (dose missing N=2). During conditioning, the most common start date of rituximab was day −6 (n=38; 19.5%), followed by day −8 (n=34; 17.4%) and day +1 (n=29; 14.8%). We also evaluated the effect of rituximab dose intensity in conditioning (375 mg/m2 vs >375 mg/m2) on transplant outcomes and noted no difference in NRM, relapse/progression, PFS or OS (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis results of patients receiving BEAM conditioning regimen and autologous HCT for DLBCL during 2003–2017 by dose group

| 375 mg/m2 (N = 104) | > 375 mg/m2 (N = 89) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | p-value |

| Non-relapse mortality | 104 | 89 | 0.96 | ||

| 1-year | 6 (2–11)% | 6 (2–11)% | 0.96 | ||

| 4-year | 12 (6–19)% | 9 (4–16)% | 0.58 | ||

| Progression/relapse | 104 | 89 | 0.45 | ||

| 1-year | 22 (15–31)% | 35 (25–45)% | 0.05 | ||

| 4-year | 40 (30–51)% | 42 (32–53)% | 0.82 | ||

| Progression-free survival | 104 | 89 | 0.46 | ||

| 1-year | 72 (63–80)% | 59 (49–69)% | 0.07 | ||

| 4-year | 48 (37–59)% | 49 (38–59)% | 0.91 | ||

| Overall survival | 104 | 89 | 0.47 | ||

| 1-year | 83 (76–90)% | 80 (71–87)% | 0.49 | ||

| 4-year | 61 (50–71)% | 57 (46–67)% | 0.59 | ||

Abbreviations: BEAM: carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan; R-BEAM: rituximab +BEAM; HR: hazard ratio; CI=: confidence interval; N: number of patients; N Eval: number evaluated; Prob: probability; auto-HCT: autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation; DLBCL: diffuse large B cell lymphoma

Causes of Death

The leading cause of death was disease relapse in both groups – 68% (n=179) in the BEAM versus 55% (n=48) in the R-BEAM cohort (Table 5). Infection was the primary cause of death in 15 (6%) BEAM cases and 6 (7%) R-BEAM cases. In addition, infection was a contributing (secondary) cause of death in 13 (5%) BEAM and 5 (6%) R-BEAM deaths.

Table 5.

Causes of death of patients receiving BEAM conditioning regimen and autologous HCT for DLBCL during 2003–2017

| BEAM | R-BEAM | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 265 | 87 |

| Primary disease | 179 (68) | 48 (55) |

| Organ failure | 19 (7) | 4 (5) |

| Infection | 15 (6) | 6 (7) |

| Second malignancy | 12 (5) | 13 (15) |

| Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome/Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 5 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Hemorrhage | 4 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Graft-versus-host disease1 | 3 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Vascular | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) |

| Other2 | 2 (<1) | 2 (2) |

| Missing | 25 (9) | 10 (11) |

4 cases had subsequent allogeneic transplantation.

Other cause: BEAM: 1 progressive multifocal encephalopathy; 1 sudden death. R-BEAM: 2 accidental death.

Infection as secondary cause of death: BEAM: 13 (5); R-BEAM: 5 (6).

Abbreviations: BEAM: carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan; R-BEAM: rituximab +BEAM; auto-HCT: autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation; DLBCL: diffuse large B cell lymphoma

Impact of Remission Status and Peri-transplant Rituximab Exposure

A higher proportion (albeit not statistically significant) of BEAM patients were in CR at auto-HCT compared to R-BEAM subjects (63% vs. 55%; p=0.07; Table 1). A subgroup analysis limited to patients in CR at auto-HCT did not show any significant differences between the BEAM and R-BEAM groups in terms of NRM, relapse/progression, PFS and OS (4-year OS 68% vs. 62%; p=0.27; for details see Supplemental Materials Table S3). In addition, a subgroup analysis limited to patients who did not receive rituximab either in the last line of therapy before HCT or during mobilization, also did not show any significant difference between BEAM and R-BEAM cohorts (Table S4).

Discussion

In this large CIBMTR analysis we evaluated the impact of adding rituximab to BEAM conditioning in DLBCL patients undergoing auto-HCT and make several important observations; R-BEAM conditioning (a) did not delay engraftment, or (b) increase the risk of early or fatal infections and that (c) there was no improvement in the relapse rate, NRM or survival compared to BEAM conditioning regimen.

In the contemporary era, the benefit of combining an anti CD20 monoclonal antibody with auto-HCT conditioning regimens is yet to be determined. Prospective data published to date incorporating rituximab with conditioning regimens are either non-randomized studies or lack a BEAM-only comparative arm. Although, the BMT CTN 0410 trial was a randomized study, the comparison was between 2 novel conditioning regimens R-BEAM and B-BEAM, with no comparative arm with standard conditioning regimens, thus not addressing our research question7. Also, BMT CTN 0410 results may have minimal clinical impact as radioimmunoconjugates are not widely used in practice due to several logistical barriers. A report by Flohr et al. suggested encouraging response rates with incorporation of rituximab in the conditioning regimen6. This study was done when the use of rituximab was not highly prevalent and the first exposure to an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody likely resulted in the observed response rates in a predominantly rituximab-naïve patient population. Similarly, a few earlier studies that primarily enrolled immunotherapy naïve patients revealed improved outcomes with incorporation of monoclonal antibody with mobilization approaches or during post-transplant period, but these findings may not be relevant in the current era of rituximab13–16.

In contrast to our study, a recent retrospective CIBMTR analysis demonstrated improved PFS in both aggressive and low-grade B cell NHL with addition of rituximab to reduc-intensity conditioning (R-RIC) regimens for allogeneic HCT17. The 3-year PFS was 56% in R-RIC versus 47% in non R-RIC group (p=0.005). However, this did not translate into better NRM or OS. Moreover, observations from the above mentioned analysis cannot be extrapolated to a clinically very different DLBCL patient population undergoing auto-HCT (as in our current analysis). Finding from our present registry analysis demonstrate that administration of rituximab with auto-HCT conditioning regimens may not yield significant benefit in the modern era, especially in patients with previous exposure to anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. Given the long half-life of rituximab, we did a subgroup analysis of patients who did not receive rituximab during the last line of therapy or mobilization and again observed no significant difference in the outcomes of the 2 conditioning regimens (BEAM vs. R-BEAM) (Table S4).

Consistent with previously published data, our analysis identified early chemoimmunotherapy failure as a poor prognostic factor for survival in both groups. In the CORAL (Collaborative Trial in Relapsed Aggressive Lymphoma) study evaluating the outcomes of 2 different pre-transplant salvage regimens, patients with early relapse (<12 months from initial diagnosis) experienced lower response rate (46% vs 88%; p=<0.001) and inferior 3-year EFS (20% vs 45%)10. This was further corroborated in the CIBMTR study that also demonstrated higher risk of relapse (relative risk 2.08; p=<0.001) and mortality post auto-HCT in DLBCL with early chemoimmunotherapy failure compared to late rituximab failure11. Additional multicenter and single institution retrospective studies have validated early rituximab-based regimen failure as a negative predictor for transplant outcomes18–20.

Center practice varies in terms of rituximab dose intensity and administration schedule in auto-HCT conditioning. While it is plausible that higher rituximab doses intensity may improve auto-HCT outcomes, in our current analysis patients who received higher dose level of rituximab (>375 mg/m2) had similar relapse rate, and survival compared to patients receiving the standard 375 mg/m2 dose (Table 4). Variations in rituximab dose applied with BEAM conditioning in our analysis (although reflective of practice variations), is a limitation we acknowledge. While the date of start of rituximab administration relative to HCT conditioning is captured in registry, the full administration schedule is not available. As a known inherent limitation with most retrospective studies, our analysis could not adjust for unknown clinical factors that could have prompted a center to add (or not to add) rituximab to BEAM conditioning (e.g. center practice, remission status at auto-HCT, history of rituximab intolerance and/or resistance etc.).

Disease relapse remains the main challenge and the primary cause for mortality post auto-HCT in DLBCL. In our cohort, progressive disease was the major cause of death in 68% and 55% of patients in the BEAM and R-BEAM group respectively. Post transplant maintenance is another treatment modality of interest in the ongoing efforts to curtail post-HCT relapse. The CORAL study that randomized patients post auto-HCT to rituximab maintenance for 1-year versus observation failed to demonstrate improvement in the CR and relapse rate, EFS and OS with maintenance therapy10. Due to lack of evidence, the ASBMT (American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation), CIBMTR, and EBMT joint consensus statement does not endorse post auto-HCT maintenance treatment in patients with DLBCL21. Results from the ongoing BMT CTN phase III randomized trial will address if maintenance ibrutinib post auto-HCT can impact outcomes in non-germinal center DLBCL (ClinicalTrials.gov # NCT02443077).

In this large CIBMTR study, addition of rituximab to BEAM conditioning regimen did not improve auto-HCT relapse rate or survival outcomes in patients with DLBCL. There was no delay in hematopoietic recovery or increased risk of early infections post auto-HCT. In the modern-era, where rituximab is an integral part of DLBCL therapy, both in the upfront and relapsed setting, additional rituximab exposure with the conditioning chemotherapy does not appear to impact transplant outcomes. Older age at transplantation and evidence of residual disease pre-transplant were associated with inferior PFS and OS. Failure of frontline chemoimmunotherapy within 1-year of diagnosis conferred higher risk of mortality. Based on our results, routine use of rituximab with BEAM conditioning prior to auto-HCT for DLBCL is not recommended.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

CIBMTR Support List

The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service grant/cooperative agreement U24CA076518 with the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); grant/cooperative agreement U24HL138660 with NHLBI and NCI; grant U24CA233032 from the NCI; grants OT3HL147741, R21HL140314 and U01HL128568 from the NHLBI; contract HHSH250201700006C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); grants N00014-18-1-2888 and N00014-17-1-2850 from the Office of Naval Research; subaward from prime contract award SC1MC31881-01-00 with HRSA; subawards from prime grant awards R01HL131731 and R01HL126589 from NHLBI; subawards from prime grant awards 5P01CA111412, 5R01HL129472, R01CA152108, 1R01HL131731, 1U01AI126612 and 1R01CA231141 from the NIH; and commercial funds from Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Adaptive Biotechnologies; Allovir, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Anthem, Inc.; Astellas Pharma US; Atara Biotherapeutics, Inc.; BARDA; Be the Match Foundation; bluebird bio, Inc.; Boston Children’s Hospital; Bristol Myers Squibb Co.; Celgene Corp.; Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles; Chimerix, Inc.; City of Hope Medical Center; CSL Behring; CytoSen Therapeutics, Inc.; Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.; Dana Farber Cancer Institute; Enterprise Science and Computing, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Gamida-Cell, Ltd.; Genzyme; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline (GSK); HistoGenetics, Inc.; Immucor; Incyte Corporation; Janssen Biotech, Inc.; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Janssen Research & Development, LLC; Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; Japan Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Data Center; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Karius, Inc.; Karyopharm Therapeutics, Inc.; Kite, a Gilead Company; Kyowa Kirin; Magenta Therapeutics; Mayo Clinic and Foundation Rochester; Medac GmbH; Mediware; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; Merck & Company, Inc.; Mesoblast; MesoScale Diagnostics, Inc.; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; Mundipharma EDO; National Marrow Donor Program; Novartis Oncology; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Omeros Corporation; Oncoimmune, Inc.; OptumHealth; Orca Biosystems, Inc.; PCORI; Pfizer, Inc.; Phamacyclics, LLC; PIRCHE AG; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; REGiMMUNE Corp.; Sanofi Genzyme; Seattle Genetics; Shire; Sobi, Inc.; Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; St. Baldrick’s Foundation; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Inc.; Takeda Oncology; The Medical College of Wisconsin; University of Minnesota; University of Pittsburgh; University of Texas-MD Anderson; University of Wisconsin - Madison; Viracor Eurofins and Xenikos BV. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Jan Cerny reports: Jazz Pharmaceuticals; Daichi-Sankyo; Incyte Inc.

Narendranath Epperla reports Speaker’s Bureau: Verastem

Timothy Fenske reports Research Support/Funding: Millennium; Kyowa, TG Therapeutics; Portola; Curtis. Consultancy: Genentech; Adaptive Biotechnologies; AbbVie; Verastem. Speaking: Genentech; Sanofi; Seattle Genetics; AstraZeneca; Celgene; Adaptive Biotechnologies.

Robert Peter Gale reports: Celgene Corporation

Mehdi Hamadani reports Research Support/Funding: Spectrum Pharmaceuticals; Astellas Pharma. Consultancy: MedImmune LLC; Janssen R &D; Incyte Corporation; ADC Therapeutics; Celgene Corporation; Pharmacyclics, Verastem. Speaker’s Bureau: Sanofi Genzyme, AstraZeneca.

Deepa Jagadeesh reports Research Support/Funding: Seattle Genetics; Regeneron pharmaceuticals; MEI Pharma; Debiopharm. Advisory board: Seattle Genetics; Atara Biotherapeutics; Kyowa Kirin.

Alberto Mussetti reports Research Support/Funding: Gilead

Richard F. Olsson reports: AstraZeneca

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All others do not have not reported any conflicts.

References:

- 1.Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trumper L, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12: 1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feugier P, Hoof AV, Sebban C, et al. Long-Term Results of the R-CHOP Study in the Treatment of Elderly Patients With Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Study by the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23: 4117–4126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfreundschuh M, Schubert J, Ziepert M, et al. Six versus eight cycles of bi-weekly CHOP-14 with or without rituximab in elderly patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphomas: a randomised controlled trial (RICOVER-60). Lancet Oncol. 2008;9: 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vellenga E, van Putten WLJ, van ‘t Veer MB, et al. Rituximab improves the treatment results of DHAP-VIM-DHAP and ASCT in relapsed/progressive aggressive CD20+ NHL: a prospective randomized HOVON trial. Blood. 2008;111: 537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346: 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flohr T, Hess G, Kolbe K, et al. Rituximab in vivo purging is safe and effective in combination with CD34-positive selected autologous stem cell transplantation for salvage therapy in B-NHL. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2002;29: 769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vose JM, Carter S, Burns LJ, et al. Phase III Randomized Study of Rituximab/Carmustine, Etoposide, Cytarabine, and Melphalan (BEAM) Compared With Iodine-131 Tositumomab/BEAM With Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Relapsed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Results From the BMT CTN 0401 Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31: 1662–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32: 3059–3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, et al. Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28: 4184–4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamadani M, Hari PN, Zhang Y, et al. Early failure of frontline rituximab-containing chemoimmunotherapy in diffuse large B cell lymphoma does not predict futility of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20: 1729–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Commenges D, Andersen PK. Score test of homogeneity for survival data. Lifetime Data Anal. 1995;1: 145–156; discussion 157–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flinn IW, O’Donnell PV, Goodrich A, et al. Immunotherapy with rituximab during peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2000;6: 628–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarella C, Zanni M, Magni M, et al. Rituximab improves the efficacy of high-dose chemotherapy with autograft for high-risk follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a multicenter Gruppo Italiano Terapie Innnovative nei linfomi survey. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26: 3166–3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khouri IF, McLaughlin P, Saliba RM. Eight-year experience with allogeneic stem cell transplantation for relapsed follicular lymphoma after nonmyeloablative conditioning with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab. Blood. 2008;111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Nishihori T, Otrock ZK, Haidar N, Mohty M, Hamadani M. Monoclonal antibodies in conditioning regimens for hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19: 1288–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epperla N, Ahn KW, Ahmed S, et al. Rituximab-containing reduced-intensity conditioning improves progression-free survival following allogeneic transplantation in B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2017;10: 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costa LJ, Maddocks K, Epperla N, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with primary treatment failure: Ultra-high risk features and benchmarking for experimental therapies. Am J Hematol. 2017;92: 161–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vardhana SA, Sauter CS, Matasar MJ, et al. Outcomes of primary refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) treated with salvage chemotherapy and intention to transplant in the rituximab era. British Journal of Haematology. 2017;176: 591–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casulo C, Friedberg JW, Ahn KW, et al. Autologous Transplantation in Follicular Lymphoma with Early Therapy Failure: A National LymphoCare Study and Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24: 1163–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanate AS, Kumar A, Dreger P, et al. Maintenance Therapies for Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas After Autologous Transplantation: A Consensus Project of ASBMT, CIBMTR, and the Lymphoma Working Party of EBMT. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5: 715–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.