Abstract

Background:

We sought to identify independent modifiable risk factors for delayed discharge after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) that have been previously underrepresented in the literature, particularly postoperative opioid use, postoperative laboratory abnormalities, and the frequency of hypotensive events.

Methods:

Data from 1033 patients undergoing TKA for primary osteoarthritis of the knee between June 2012 and August 2014 at an academic orthopedic specialty hospital were reviewed. Patient demographics, comorbidities, inpatient opioid medication, postoperative hypotensive events, and abnormalities in laboratory values, all occurring on postoperative day 0 or 1, were collected. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent risk factors for a prolonged length of stay (LOS) >3 days.

Results:

The average age of patients undergoing primary TKA in our cohort was 65.9 (standard deviation, 9.1) years, and 61.7% were women. The mean LOS for all patients was 2.64 days (standard deviation, 1.14; range, 1–9). And 15.3% of patients had a LOS >3 days. On multivariate logistic regression analysis, nonmodifiable risk factors associated with a prolonged LOS included nonwhite race (odds ratio [OR], 2.01), single marital status (OR, 1.53), and increasing age (OR, 1.47). Modifiable risk factors included every 5 postoperative hypotensive events (OR, 1.31), 10-mg increases in oral morphine equivalent consumption (OR, 1.04), and postoperative laboratory abnormalities (hypocalcemia: OR, 2.15; low hemoglobin: OR, 2.63).

Conclusion:

This study identifies potentially modifiable factors that are associated with increased LOS after TKA. Doubling down on efforts to control the narcotic use and to use opioid alternatives when possible will likely have efficacy in reducing LOS. Attempts should be made to correct laboratory abnormalities and to be cognizant of patient opioid use, age, and race when considering potential avenues to reduce LOS.

Keywords: total knee arthroplasty, opioid, hypotension, modifiable risk factors, length of stay, anemia

Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) is the most frequently performed inpatient medical procedure performed in the United States, with total knee arthroplasty (TKA) representing a majority of the cases with over 600,000 being performed in 2012 alone [1]. A recent analysis using the National Inpatient Sample estimated the growth in number of TKA performed in the United States to increase by 71% to 1.26 million annual procedures by the year 2030 [2]. Given this increasing demand, the annual national healthcare expenditure for TKA will increase with the rising incidence. In 2014 alone, the annual national healthcare expenditure for these operations was approximately 20 billion dollars, and this amount has been increasing annually [3].

One of the major drivers of the cost associated with TKA is the hospital length of stay (LOS) after the procedure. From 2002 to 2013, the hospital LOS after TKA decreased from a mean time of 4.06 to 2.97 days. Despite a 52.4% increase in mean costs of TKA in this same time period, the mean hospital costs would have increased a further 18.5% with hospital LOS kept at the 2002 level. Reducing the LOS appeared to be one successful approach to slowing the pace of ever-increasing hospital costs for TKA [4].

Despite recent reports of decreasing LOS for TKA in the United States, LOS remains high in other parts of the world. A recent study published in 2017 of a cohort of 1622 patients from Hong Kong receiving TKA was identified as having a mean LOS of 6.8 days after the procedure [5]. In a study using data from the National Health Institute in the United Kingdom, the mean hospital LOS remained high at 5.4 days [6]. While these reported numbers are higher than a previously reported mean LOS of 3.5 for TKA, LOS remains a variable of interest from a cost reduction standpoint. As the financial landscape of healthcare is set to undergo significant changes, efforts aimed at decreasing LOS after TKA is one potential target to help contain and potentially decrease healthcare costs associated with these procedures [7–10].

Much effort has been undertaken to analyze factors contributing to increased LOS in the hospital after orthopedic surgery [10–17]. Additionally, several articles have examined factors associated specifically with increased LOS for TKA [5,18–23]. Most investigate nonmodifiable patient characteristics, such as race, age, income, body mass index, various comorbidities, and insurance status. These factors, however, are not potential targets of modification from a cost and LOS reduction standpoint. Interestingly, less focus has been given to the study of potentially modifiable risk factors, such as opioid use, abnormal vital signs, or significantly altered postoperative laboratory values which may affect LOS. One factor particularly, postoperative hypotension, has been shown to increase LOS in other surgical fields, and in total hip arthroplasty [16,24,25]. There are clinical protocols that exist to facilitate fluid management after TJA, but the effect of postoperative hypotension specifically on LOS has been inadequately evaluated [26,27].

Therefore, this study used single-institution data from an academic orthopedic specialty hospital to identify individuals undergoing TKA and investigate potentially modifiable risk factors affecting LOS, with a focus on opioid use, postoperative laboratory abnormalities, and the frequency of hypotensive events. Our primary outcome measure was hospital LOS. We hypothesized that, similar to other surgical specialties, the number of acute postoperative hypotensive events after TKA would be correlated to an increase in the average patient LOS. We also hypothesized that increased narcotic consumption in the postoperative period would also be associated with an increased LOS. In seeking to determine whether an independent association existed between these modifiable risk factors and LOS, we also included other patient characteristics, such as demographic information, comorbidities, and insurance status in our analysis.

Patients and Methods

Upon acceptance from the institutional review board at our institution, all patients undergoing primary TKA between June 2012 and August 2014 were identified. All of these procedures were performed by 1 of the 4 fellowship-trained surgeons at our institution who all work and operate at an orthopedic specialty hospital. None of the 1033 patients were excluded from our analysis based on death resulting from their TKA procedure or the resulting hospital stay, given a mortality rate of 0.0%. Only patients receiving surgical TKA for primary knee osteoarthritis were included in final analyses.

The primary outcome measure of interest was hospital LOS. We chose to define this measure based categorically as number of days (0, 1, 2, 3, etc.). To determine hospital LOS, each night spent in the hospital after surgery was determined to be an increase in LOS of 1 day. To illustrate this, if a patient were to be discharged on the day following their procedure, they would have spent 1 night in the hospital and thus accrued a total LOS of 1 day. Despite potential value in determining hour-by-hour LOS after TKA, efforts were not made to distinguish exact timing of discharge due to lack of available, reliably accurate data of exact time of discharge. No patients were admitted to the hospital before the day of their TKA procedure.

After collection of data (patient demographics, comorbidities, inpatient opioid medication use, postoperative hypotension, and abnormal laboratory values) from retrospective chart review, a model was created to examine both modifiable and nonmodifiable predictors of LOS. In an effort to assess and account for patient comorbidities, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was computed for each patient using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) categories [28,29]. To effectively assess opioid use, total narcotic medication used was converted to oral morphine equivalents (OME) for each patient [30]. Postoperative hypotensive events were noted and were recorded as a continuous variable. These events were defined as a systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure less than 60 mmHg for any single reading [31,32].

The default threshold laboratory values coded within our institution’s electronic medical record system (Cerner Systems) as clinical support tools were used as threshold values to determine patient laboratory result aberrancy. We have listed the thresholds used in our study in Table 1. Abnormal high or abnormal low values (values deviating from threshold ranges) were then recorded categorically (either as “abnormal high” or “abnormal low”) for each postoperative day (POD) in a retrospective review of patient data during the hospital stay for TKA. Laboratory data were not recorded in a continuous fashion.

Table 1.

Laboratory Reference Ranges.

| Lab Variable | Lowa | Higha |

|---|---|---|

| Albumin | 3.5 | 5 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 38 | 126 |

| Anion gap | 2 | 12 |

| Osmolality, calculated | 261 | 280 |

| Bilirubin, total | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| Calcium, total | 8.4 | 10.5 |

| Chloride | 98 | 107 |

| Carbon dioxide | 22 | 30 |

| Creatinine | 0.66 | 1.25 |

| Glucose | 74 | 106 |

| Potassium | 3.5 | 5.1 |

| Protein, total | 6.3 | 8.2 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 15 | 46 |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 21 | 72 |

| Sodium | 137 | 145 |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 9 | 20 |

| Hemoglobin | 11.4 | 16.1 |

| Hematocrit | 33.3 | 46.5 |

To be classified as low or high, value must be below or above cutoff.

Abnormal laboratory variables that appeared infrequently (defined as appearing in less than 5% of the sample) were noted and such variables were excluded in an effort to preserve the reliability of our model. After removing infrequent variables, the presence of low calcium, high creatinine, high glucose, low hemoglobin, and low sodium the laboratory values occurring in at least 5% of our sample, and thus included in the final regression model. Baseline characteristics of all of the patients included in our sample can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Class | Mean ± SD (Min, Max) % (N) |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1033 | |

| Age (y) | 65.9 ± 9.11 (33.0, 89.0) | |

| OME (mg); first 2 d | 208.7 ± 137.1 (0, 1806) | |

| Sex | Female | 61.7% (637) |

| Male | 38.3% (396) | |

| Race | White | 72.2% (746) |

| Nonwhite | 27.8% (287) | |

| Marital status | Married | 68.9% (712) |

| Not married | 31.1% (321) | |

| CCI score | 0.60 ± 0.86 (0, 3) | |

| Insurance | HMO/managed care | 31.3% (323) |

| Medicaid | 1.6% (16) | |

| Medicare | 55.5% (572) | |

| Other | 11.6% (120) | |

| Lab abnormalities; first 2 d | Low calcium | 40.0% (413) |

| High creatinine | 66.55% (687) | |

| High glucose | 55.7% (575) | |

| Low hemoglobin | 73.7% (761) | |

| Low sodium | 37.6% (388) | |

| Days of IV narcotic use | 1.46 ± 0.90 (0, 6) | |

| Narcotic use on day 0/1 | 92.5% (955) |

OME, oral morphine equivalents; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; IV, intravenous; HMO, Health Maintenance Organization.

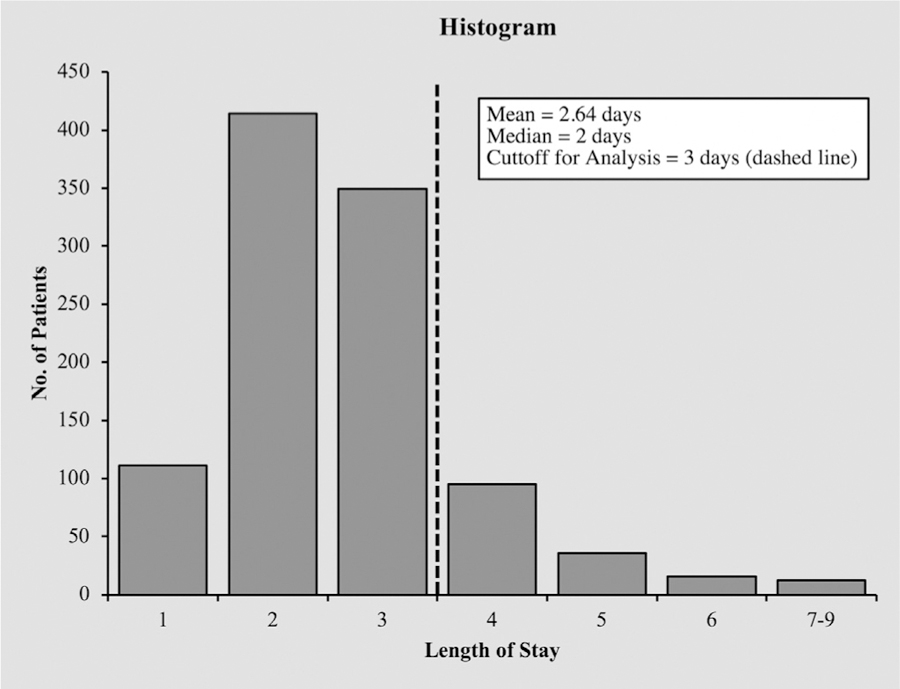

In grouping patients as having either increased or “normal” LOS, we chose to use a cutoff of LOS >3 days. As 84.7% (845/1033) of our cohort had a LOS ≤3 days, a sizable group of 188 patients were isolated and defined as having a prolonged LOS. See histogram (Figure 1) for LOS distribution.

Fig. 1.

Graph shows a histogram of length of stay after total knee arthroplasty. The dashed line is at 3 days and represents the cutoff used for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out by an institutional statistician using the R:A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.R-project.org). χ2 or Fisher exact tests were performed for categorical data, and Student t-tests were performed for parametric continuous data. After these initial tests, variables with a significance of P < .05 were then entered into a multivariate model. Specifically, a binary logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent risk factors for LOS >3 days. This model also serves to effectively control for confounding variables. Using this model, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for associations between each risk factor and outcomes of interest.

To indicate spread and reliability of the model, values are presented in this study as a mean with standard deviation (SD) or 95% CIs. Two-tailed P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. ORs for OME and age are presented per 10-unit increase (mg or years as applicable). ORs for hypotensive events on POD 0 or 1 are reported per 5 events. ORs for CCI is presented per 1-unit increase. Because laboratory abnormalities beyond POD 0 or 1 are unlikely to be related to potentially modifiable risk factors for increased LOS, only patients with laboratory abnormalities in POD 0 or 1 were considered to have laboratory aberrancy as a risk factor for prolonged LOS.

Results

One thousand and thirty-three patients underwent TKA for primary osteoarthritis of the knee between June 2012 and August 2014 at our academic orthopedic specialty hospital. The average age of patients undergoing primary TKA in our cohort was 65.9 (SD, 9.1) years; 61.7% were women, and 38.3% were men. The median for LOS was 2 days, and the mode for LOS was also 2 days. Also, 50.8% of patients were discharged before POD 3 (≤2 POD), 10.7% (111/1033) were discharged on POD 0 or 1, and 74.0% (764/1033) were discharged on POD 2 or 3. The remaining 15.3% (188/1033) made up the group of “high risk” patients and were discharged on or above POD 4 (Figure 1). The mean LOS for all patients was 2.64 days (SD, 1.14; range, 1, 9). Surgeon performing the procedure did not significantly affect LOS.

Univariate analysis comparing patients with a prolonged LOS >3 days (“high risk” patients) to those with a LOS ≤3 days demonstrated numerous preoperative and postoperative factors associated with an increased LOS (Table 3). The postoperative modifiable risk factors correlated with a prolonged LOS included any narcotic use at all, OME, the number of hypotensive events, postoperative anemia, hypocalcemia, hyponatremia, high glucose, and high creatinine. The nonmodifiable variables which yielded an increase in LOS included an increasing age, female gender, Medicare insurance payer type, CCI, single marital status, and non-Caucasian race.

Table 3.

Univariate Logistic Regression for Predictors of Delayed Discharge.

| Characteristic | Class | LOS 0–1 d (N = 111) | LOS 2–3 d (N = 764) | LOS >3 d (N = 158) | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotensive events (POD 0/1)a,b | 2.32 (2.69) | 3.15 (3.24) | 3.96 (3.98) | 1.545 (1.297–1.841) | <.0001 | |

| CCI score | 0.39 (0.62) | 0.57 (0.84) | 0.87 (1.0) | 1.469 (1.254–1.721) | <.0001 | |

| Sex | Male | 63/111 (56.7%) | 295/764 (38.6%) | 38/158 (24.1%) | — | <.0001 |

| Female | 48/111 (43.2%) | 469/764 (61.4%) | 120/158 (75.9%) | 2.252 (1.672–3.03) | ||

| Race | White | 94/111 (84.7%) | 556/764 (72.8%) | 96/158 (60.8%) | 1.988 (1.458–2.703) | <.0001 |

| Nonwhite | 17/111 (15.3%) | 208/764 (27.2%) | 62/158 (39.2%) | 1.988 (1.458–2.703) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 91/111 (82.0%) | 533/764 (69.8%) | 88/158 (55.7%) | — | <.0001 |

| Not married | 20/111 (18.0%) | 231/764 (30.2%) | 70/158 (44.3%) | 2.04 (1.511–2.755) | ||

| Agea,c | 63.9 (8.9) | 65.7 (9.2) | 68.5 (8.5) | 1.38 (1.190–1.612) | <.0001 | |

| OME (mg)a,c | 101.1 (64.5) | 218.3 (138.6) | 237.1 (133.6) | 1.037 (1.026–1.049) | <.0001 | |

| Insurance | HMO/managed care | 49/111 (44.1%) | 235/762 (30.8%) | 39/158 (24.7%) | 1.171 (0.726–1.886) | <.0001 |

| Medicaid | 2/111 (1.8%) | 12/762 (1.6%) | 2/158 (1.3%) | 1.352 (0.409–4.470) | ||

| Medicare | 42/111 (37.8%) | 423/762 (55.5%) | 107/158 (67.7%) | 2.260 (1.436–3.558) | ||

| Other | 18/111 (16.2%) | 92/762 (12.1%) | 10/158 (6.3%) | — | ||

| Lab abnormalities | Low calcium | 20/111 (18.0%) | 306/764 (40.1%) | 87/158 (55.1%) | 2.413 (1.801–3.234) | <.0001 |

| High creatinine | 60/111 (54.1%) | 509/764 (66.6%) | 118/158 (74.7%) | 1.690 (1.255–2.275) | .0006 | |

| High glucose | 50/111 (45.1%) | 420/764 (55.0%) | 105/158 (66.5%) | 1.667 (1.257–2.211) | .0004 | |

| Low hemoglobin | 39/111 (35.1%) | 583/764 (76.3%) | 139/158 (88.0%) | 5.049 (3.546–7.190) | <.0001 | |

| Low sodium | 27/111 (24.3%) | 285/764 (37.3%) | 76/158 (48.1%) | 1.779 (1.334–2.372) | <.0001 | |

| Narcotic use on day 0/1 | 88/111 (79.3%) | 714/764 (93.5%) | 153/158 (96.8%) | 3.819 (2.307–6.320) | <.0001 |

LOS, length of stay; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; POD, postoperative day; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; OME, oral morphine equivalents; SD, standard deviation; HMO, Health Maintenance Organization.

Variables presented as mean ± SD.

OR reported per 5 events.

OR reported per 10 units (years or mg as applicable).

Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis effectively controlled for confounding factors and identified several independent risk factors for delayed discharge (Table 4). Nonmodifiable risk factors included single marital status (52.6% increased odds) and nonwhite race (101.2% increased odds). For every 10-year increase in age, there was a 46.5% increased odds of an increased LOS. Insurance status, sex, and CCI score were not independent predictors of an increased LOS.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis of Risk Factors Significantly Associated With Length of Stay >3 Days.

| Characteristic | Class | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotensive events on POD 0/1a,b | 1.305 (1.036–1.645) | .0239 | |

| Race | Nonwhite vs white | 2.012 (1.437–2.817) | <.0001 |

| Marital status | Not married vs married | 1.526 (1.101–2.119) | <.0001 |

| Agea,c | 1.465 (1.163–1.845) | <.0001 | |

| OME (mg)a,c | 1.044 (1.030–1.058) | <.0001 | |

| Lab abnormalities | Low calcium | 2.149 (1.463–3.157) | <.0001 |

| Low hemoglobin | 2.625 (1.760–3.914) | <.0001 | |

| Narcotic use on day 0/1 | 1.903 (1.090–3.323) | <.0001 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; POD, postoperative day; OME, oral morphine equivalents; SD, standard deviation.

Variables presented as mean ± SD.

OR reported per 5 additional events.

OR reported per 10 units (years or mg as applicable).

Additionally, and more importantly, we identified several modifiable risk factors for a prolonged LOS following TKA. For every 5 additional hypotensive events during POD 0 and 1, there was a 30.5% increased odds of a hospital LOS >3 days. Similarly, for every 10-mg increase in OME use during POD 0 and 1, there was a 4.4% increased odds of a LOS >2 days. Hypocalcemia occurring in POD 0 or 1 contributed to a 114.9% increased odds of a LOS past 3 days. The strongest association between any risk factor and LOS in our model was that of low hemoglobin; patients with low hemoglobin values on POD 0 or 1 had 2.625 increased odds of a LOS >3 days than those without abnormal hemoglobin values on those days. When controlling for the effect of other variables in our multivariate model, several potentially modifiable variables that were significant on univariate analysis were no longer significant predictors for delayed discharge, including high glucose, high creatinine, and low sodium.

Discussion

Hospital LOS is a modifiable risk factor in decreasing the rising hospital costs associated with TKA. As decreased LOS is not associated with an increased readmission rate or increased emergency room visits following TKA, identifying risk factors for an increased LOS after TKA can help constrain hospital costs while providing rapid discharge home [33].

Our patients had a mean LOS of 2.64 days—lower than published estimates, which have reported a mean LOS ranging from 3.17 days to 6.8 days for TKA [5,7,8,34]. This median LOS is also lower than published estimates in similar literature looking at risk factors associated with prolonged LOS [22,35]. The shorter LOS observed in our institution’s patients may be due partly to each surgeon’s fellowship training and that a majority of the surgeon’s surgical caseload was comprised of TKA. In addition, each surgeon worked in the same orthopedic-specific hospital that employs an early, aggressive physical therapy protocol and uniformly defined clinical pathways, which has been reported to reduce LOS in patients undergoing TJA [20,36–38].

Modifiable Risk Factors

Most importantly, our results confirm additional and modifiable risk factors for increased hospital LOS after TKA. Specifically, postoperative hypotensive events, OME, and opioid use during the day of surgery and POD 1 were independent and significant risk factors for increased hospital stay. These data thus support future research into initiatives aimed at reducing early postoperative hypotension and opioid use in patients undergoing TKA.

Our analysis revealed a strong correlation between increasing use of OME and odds of LOS being greater than 3 days. Average OME for patients who had a LOS >3 days was 237.1 as compared to 101.1 OME in the cohort of patients with LOS between 0 and 1 days. Other studies have revealed similar findings across other fields of medicine, where opioid use is associated with increased LOS and readmission rate [39]. Additionally, opioid-related adverse events (constipation, nausea, confusion) have been determined to directly impact LOS in patients receiving orthopedic surgery [40]. Doubling down on efforts to control the narcotic epidemic and to use opioid alternatives when possible will likely have profound efficacy in reducing LOS. These replacements could include intraoperative dexamethasone, which has been supported as an effective conduit for reducing pain, nausea, and LOS (by up to 1.5 days) after TJA and was recently put in place at our institution after the study period of this article was completed [41]. There are certain deleterious side effects to be aware of when using any glucocorticoid, including infection, surgical site healing, or osteonecrosis. However, to our knowledge, no studies have found arthroplasty patients to be at increased risk of these complications and can be safely given to arthroplasty candidates in low-to-moderate doses [42–46]. One potential complication with intraoperative dexamethasone is fluctuations in blood glucose levels, which have been found to be higher at 24 hours [46].

Additionally, other opioid alternatives may play a role in reducing LOS via reducing opioid use. Consistent use of nonopioid analgesia, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories and acetaminophen, but also gabapentin and selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors, has been shown to reduce postoperative opioid requirements [47–49]. Cryotherapy has been shown to reduce postoperative pain and opioid requirements, with no to minimal side effects, which can include discomfort, local skin reactions, or coldrelated injuries, including case reports of frostbite that required debridement [50–53]. Furthermore, multimodal pain control strategies with a peripheral nerve block as the emphasis of pain control decreased opioid use and LOS [54]. Preoperative and postoperative opioid education has also been shown to be effective in reducing postoperative opioid use for a number of orthopedic procedures [55–57], in addition to the implementation of a hospital-wide opioid prescription protocol [58].

Our results also confirm that several laboratory values are independently associated with increased LOS, and protocols to correct these aberrant laboratory values could also prove valuable to reduce hospital stay after TKA. Specifically, as low postoperative hemoglobin had the highest correlation with increased LOS of any risk factor (OR, 2.63), research to determine an appropriate postoperative hemoglobin threshold for transfusion and a subsequent postoperative TKA transfusion protocol to optimize patient outcomes and LOS may substantially reduce average hospital stay for patients undergoing TKA. Tranexamic acid has been found to decrease blood loss and control postoperative drops in hemoglobin and should be used to control intraoperative blood loss [59–61]; however, its role in reducing LOS remains undetermined. We do not use tourniquets for bleeding control because of a potential increased risk of thromboembolic events with no differences in postoperative blood loss [62,63]. Furthermore, TXA has been found to be superior to tourniquets in a randomized, controlled trial, with decreased blood loss and postoperative pain [64].

For the vast majority of our patients, a preoperative complete blood count is available from an outside provider or within the network. If this shows an anemia with a hemoglobin less than 12, the patient undergoes an anemic work-up before scheduling surgery. If they have a history of anemia symptomology, and they do not have a preoperative hemoglobin, a complete blood count is performed. We currently do not assess preoperative hemoglobin in asymptomatic without a laboratory value from an outside provider. Furthermore, to control hypotension, our routine practice is clear liquids up to 2 hours before surgery. Antihypertensives as a general rule are not resumed until the systolic blood pressure is above 160 mmHg or until they are discharged home.

In addition, our analysis confirmed other laboratory aberrancies are associated with a prolonged LOS. Hypocalcemia was the second single highest risk factor of prolonged LOS after a low postoperative hemoglobin (OR, 2.15). To this research team’s knowledge, this has yet to be reported as a risk factor for prolonged LOS after TKA. We hypothesize that hypocalcemia indicates a state of patient frailty or of improper nutrition which may contribute to an increased LOS after TKA. Ensuring adequate control and treatment of both preoperative and postoperative hypocalcemia could further decrease LOS for patients undergoing TKA.

Nonmodifiable Risk Factors

In addition, our results confirm several previously identified nonmodifiable risk factors for increased hospital LOS after TKA. Specifically, non-Caucasian race, single marital status, and increasing age were all independently associated with increased hospital LOS in our model (Table 4). Of note, when studied in isolation, Medicare insurance holders had an increased LOS compared to private insurance holders; however, when adjusted for all other variables, these associations regarding insurance status were no longer statistically significant (Tables 3 and 4). This is in opposition to previously reported literature in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database, which found Medicaid payer status to be a risk factor for prolonged LOS [65]. However, this study had a higher median LOS compared to our average of 2 days, and the multivariate analysis used in this study was looking for risk factors for increased LOS of over 4 days, a full day longer than our cutoff.

The CCI was associated with a prolonged LOS when studied in isolation; however, an increase in CCI had no statistically significant value in predicting an increased LOS when controlling for other variables. This may be in part laboratory abnormalities being included in our model, and these abnormality derangements may be a more concerning indicator of patient health than the CCI.

While more work needs to be done to determine appropriate protocols for reducing the impact of modifiable risk factors and potentially decreasing postoperative LOS, properly identifying modifiable targets as a first step is imperative. In attempting to do so, this study has several strengths. This study has a large sample size of 1033 patients giving it considerable power to detect the relative impact of various risk factors. Other single-institution studies investigating risk factors for prolonged LOS did not have the same sample size as this study [19,22]. Additionally, unlike national health databases with data aggregated from numerous facilities with varied protocols and orthopedic surgeons with heterogeneous caseloads, our patients were all treated by surgeons performing greater than 200 TKA procedures each year, at the same institution with the same protocols. Thus, more standardized data such as vital signs, laboratory values, and medication use can be gleaned and examined across our sample. This may explain why our data did not show low sodium, glucose, or high creatinine as a risk factor for prolonged LOS. Additionally, the different cut offs for statistical analysis may also explain the differing results in these studies.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study also has some limitations. These include the retrospective nature of the study and the fact that all patient information was derived from medical charts and records and not recorded prospectively at the time of operation. As such, not all variables of interest, such as the presence of orthostatic hypotension or time of first postoperative physical therapy session, were recorded uniformly and thus could not be included in our model unfortunately. Our study also employs a conservative threshold to define hypotension as any reading with a systolic pressure of 90 mmHg or less or a diastolic pressure of 60 mmHg or less. These thresholds have been defined previously in the literature [31,32]. Certainly, the possibility that blood pressure values that are greater than a systolic pressure of 90 mmHg or a diastolic pressure of 60 mmHg may still be considered an abnormality on the continuum of postoperative blood pressure. Many of the patients in our cohort have baseline hypertension, and so even values significantly higher than the aforementioned thresholds may still constitute a hypotensive event. Future research, therefore, could aim to control for preoperative hypertension in accounting for all possible events of postoperative hypotension. In this way, the survey could be adequately sampled, and patients who may not meet the threshold values for hypotension due to baseline hypertension would still be recorded correctly as having had a hypotensive event in the postoperative period. Other factors such as anesthesia type (general or spinal) and tranexamic acid (TXA) are other modifiable, physician-driven factors that have been shown to decrease LOS and reduce postoperative hemoglobin loss, respectively [60,66–68]. However, the use of spinal anesthesia or the use of TXA was implemented after the study period at our institution, so their effect on LOS could not be determined for the present study.

Lastly, laboratory values were coded as abnormal low, normal, or abnormal high as described above in a categorical fashion. Continuous laboratory data were not included in our model. Therefore, the magnitude of laboratory derangements remains unexplored in our multivariate model. Further investigation could aim to quantify the effect on hospital LOS of specific magnitudes of laboratory variable aberrance. Additionally, our estimations for abnormal values (based on default threshold laboratory values coded within our institution’s electronic medical record system) could be considered conservative in some cases, especially a hemoglobin cutoff of 11.4. Furthermore, there have been increases in outpatient TKA because the study period ended in 2014, so it is possible that some of the factors that we have found do not have meaning for the much shorter LOS in 2019. However, predictive models suggest that until the year 2026, over 50% of TJAs will take place in the inpatient setting; thus, the data presented here remains relevant [69].

We intend our study to serve as an initial examination of potentially modifiable risk factors for increased hospital LOS after TKA. We hope that further investigation will explore each variable documented in this study that was found to be correlated with hospital LOS in an effort to define specific contribution to LOS of various magnitudes of aberrancy. Such research could then be used to direct protocols and policies aimed at reducing hospital LOS and overall system burden of one of the most commonly performed procedures in the United States.

Conclusion

As TKA continues to grow in incidence throughout the United States, great import has been placed on attempting to reduce hospital LOS after this procedure and therefore restrain expenditures. This study demonstrates that increased opioid use, hypotensive events, and abnormal calcium and hemoglobin are all independently associated with a longer hospital LOS after TKA. It is important to identify these and other potentially modifiable factors that may improve patient safety while reducing potential burdens.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors of this paper have disclosed potential or pertinent conflicts of interest, which may include receipt of payment, either direct or indirect, institutional support, or association with an entity in the biomedical field which may be perceived to have potential conflict of interest with this work. For full disclosure statements refer to https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2019.07.047.

References

- [1].Inacio MCS, Paxton EW, Graves SE, Namba RS, Nemes S. Projected increase in total knee arthroplasty in the United States - an alternative projection model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017;25:1797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the U.S., 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2018;100:1455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Walenkamp MM, de Muinck Keizer RJ, Goslings JC, Vos LM, Rosenwasser MP, Schep NW. The minimum clinically important difference of the patient-rated wrist evaluation score for patients with distal radius fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015;473:3235–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Molloy IB, Martin BI, Moschetti WE, Jevsevar DS. Effects of the length of stay on the cost of total knee and total hip arthroplasty from 2002 to 2013. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99:402–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lo CK, Lee QJ, Wong YC. Predictive factors for length of hospital stay following primary total knee replacement in a total joint replacement centre in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2017;23:435–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Burn E, Edwards CJ, Murray DW, Silman A, Cooper C, Arden NK, et al. Trends and determinants of length of stay and hospital reimbursement following knee and hip replacement: evidence from linked primary care and NHS hospital records from 1997 to 2014. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cram P, Lu X, Kaboli PJ, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Cai X, Wolf BR, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of Medicare patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty, 1991–2008. JAMA 2011;305:1560–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991–2010. JAMA 2012;308:1227–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Iorio R, Clair AJ, Inneh IA, Slover JD, Bosco JA, Zuckerman JD. Early results of medicare’s bundled payment Initiative for a 90-day total joint arthroplasty episode of care. J Arthroplasty 2015;31:343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hart A, Bergeron SG, Epure L, Huk O, Zukor D, Antoniou J. Comparison of US and Canadian perioperative outcomes and hospital efficiency after total hip and knee arthroplasty. JAMA Surg 2015;150:990–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dall GF, Ohly NE, Ballantyne JA, Brenkel IJ. The influence of pre-operative factors on the length of in-patient stay following primary total hip replacement for osteoarthritis: a multivariate analysis of 2302 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009;91:434–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rissman CM, Keeney BJ, Ercolano EM, Koenig KM. Predictors of facility discharge, range of motion, and patient-reported physical function improvement after primary total knee arthroplasty: a prospective cohort analysis. J Arthroplasty 2015;31:36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Styron JF, Koroukian SM, Klika AK, Barsoum WK. Patient vs provider characteristics impacting hospital lengths of stay after total knee or hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011;26:1418–14126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Winemaker M, Petruccelli D, Kabali C, de Beer J. Not all total joint replacement patients are created equal: preoperative factors and length of stay in hospital. Can J Surg 2015;58:160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Halawi MJ, Vovos TJ, Green CL, Wellman SS, Attarian DE, Bolognesi MP. Preoperative predictors of extended hospital length of stay following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:361–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Farley KX, Anastasio AT, Premkumar A, Boden SD, Gottschalk MB, Bradbury TL. The influence of modifiable, postoperative patient variables on the length of stay after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2019;34:901–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Aizpuru M, Staley C, Reisman W, Gottschalk MB, Schenker ML. Determinants of length of stay after operative treatment for femur fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2018;32:161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Carter EM, Potts HW. Predicting length of stay from an electronic patient record system: a primary total knee replacement example. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2014;14:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jonas SC, Smith HK, Blair PS, Dacombe P, Weale AE. Factors influencing length of stay following primary total knee replacement in a UK specialist orthopaedic centre. Knee 2013;20:310–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mears SC, Edwards PK, Barnes CL. How to decrease length of hospital stay after total knee replacement. J Surg Orthop Adv 2016;25:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ong PH, Pua YH. A prediction model for length of stay after total and unicompartmental knee replacement. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:1490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Raut S, Mertes SC, Muniz-Terrera G, Khanduja V. Factors associated with prolonged length of stay following a total knee replacement in patients aged over 75. Int Orthop 2012;36:1601–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Smith ID, Elton R, Ballantyne JA, Brenkel IJ. Pre-operative predictors of the length of hospital stay in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90: 1435–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tassoudis V, Vretzakis G, Petsiti A, Stamatiou G, Bouzia K, Melekos M, et al. Impact of intraoperative hypotension on hospital stay in major abdominal surgery. J Anesth 2011;25:492–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Jorgensen CC, Jorgensen TB, Ruhnau B, Secher NH, Kehlet H. Orthostatic intolerance and the cardiovascular response to early postoperative mobilization. Br J Anaesth 2009;102:756–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Husted H, Lunn TH, Troelsen A, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen BB, Kehlet H. Why still in hospital after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 2011;82:679–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Berger RA, Sanders SA, Thill ES, Sporer SM, Della Valle C. Newer anesthesia and rehabilitation protocols enable outpatient hip replacement in selected patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:1424–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Selker HP, Beshansky JR, Pauker SG, Kassirer JP. The epidemiology of delays in a teaching hospital. The development and use of a tool that detects unnecessary hospital days. Med Care 1989;27:112–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tomei KL, Doe C, Prestigiacomo CJ, Gandhi CD. Comparative analysis of state-level concussion legislation and review of current practices in concussion. Neurosurg Focus 2002;33:E11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ben-David B, Frankel R, Arzumonov T, Marchevsky Y, Volpin G. Minidose bupivacaine-fentanyl spinal anesthesia for surgical repair of hip fracture in the aged. Anesthesiology 2000;92:6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Guichard JL, Desai RV, Ahmed MI, Mujib M, Fonarow GC, Feller MA, et al. Isolated diastolic hypotension and incident heart failure in older adults. Hypertension 2011;58:895–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Stone AH, Dunn L, MacDonald JH, King PJ. Reducing length of stay does not increase emergency room visits or readmissions in patients undergoing primary hip and knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty 2018;33:2381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Basques BA, Tetreault MW, Della Valle CJ. Same-day discharge compared with inpatient hospitalization following hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99:1969–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Guerra ML, Singh PJ, Taylor NF. Early mobilization of patients who have had a hip or knee joint replacement reduces length of stay in hospital: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil 2015;29:844–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Maempel JF, Walmsley PJ. Enhanced recovery programmes can reduce length of stay after total knee replacement without sacrificing functional outcome at one year. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2015;97:563–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Maidment ZL, Hordacre BG, Barr CJ. Effect of weekend physiotherapy provision on physiotherapy and hospital length of stay after total knee and total hip replacement. Aust Health Rev 2014;38:265–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Weingarten SR, Conner L, Riedinger M, Alter A, Brien W, Ellrodt AG. Total knee replacement. A guideline to reduce postoperative length of stay. West J Med 1995;163:26–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gulur P, Williams L, Chaudhary S, Koury K, Jaff M. Opioid tolerance–a predictor of increased length of stay and higher readmission rates. Pain Physician 2014;17:E503–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pizzi LT, Toner R, Foley K, Thomson E, Chow W, Kim M, et al. Relationship between potential opioid-related adverse effects and hospital length of stay in patients receiving opioids after orthopedic surgery. Pharmacotherapy 2012;32:502–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Backes JR, Bentley JC, Politi JR, Chambers BT. Dexamethasone reduces length of hospitalization and improves postoperative pain and nausea after total joint arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2013;28(8 Suppl):11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Salerno A, Hermann R. Efficacy and safety of steroid use for postoperative pain relief. Update and review of the medical literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:1361–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sauerland S, Nagelschmidt M, Mallmann P, Neugebauer EA. Risks and benefits of preoperative high dose methylprednisolone in surgical patients: a systematic review. Drug Saf 2000;23:449–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Henzi I, Walder B, Tramer MR. Dexamethasone for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a quantitative systematic review. Anesth Analg 2000;90:186–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bergeron SG, Kardash KJ, Huk OL, Zukor DJ, Antoniou J. Perioperative dexamethasone does not affect functional outcome in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:1463–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Waldron NH, Jones CA, Gan TJ, Allen TK, Habib AS. Impact of perioperative dexamethasone on postoperative analgesia and side-effects: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2013;110:191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Eckhard L, Jones T, Collins JE, Shrestha S, Fitz W. Increased postoperative dexamethasone and gabapentin reduces opioid consumption after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2019;27:2167–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ho KY, Tay W, Yeo MC, Liu H, Yeo SJ, Chia SL, et al. Duloxetine reduces morphine requirements after knee replacement surgery. Br J Anaesth 2010;105:371–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lunn TH, Frokjaer VG, Hansen TB, Kristensen PW, Lind T, Kehlet H. Analgesic effect of perioperative escitalopram in high pain catastrophizing patients after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2015;122:884–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chughtai M, Sodhi N, Jawad M, Newman JM, Khlopas A, Bhave A, et al. Cryotherapy treatment after unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty: a review. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:3822–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Adie S, Kwan A, Naylor JM, Harris IA, Mittal R. Cryotherapy following total knee replacement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:CD007911. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [52].Ni SH, Jiang WT, Guo L, Jin YH, Jiang TL, Zhao Y, et al. Cryotherapy on postoperative rehabilitation of joint arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:3354–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Dundon JM, Rymer MC, Johnson RM. Total patellar skin loss from cryotherapy after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2013;28:376 e5-e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ellis TA 2nd, Hammoud H, Dela Merced P, Nooli NP, Ghoddoussi F, Kong J, et al. Multimodal clinical pathway with adductor canal block decreases hospital length of stay, improves pain control, and reduces opioid consumption in total knee arthroplasty patients: a retrospective review. J Arthroplasty 2018;33:2440–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Farley KX, Anastasio AT, Kumar A, Premkumar A, Gottschalk MB, Xerogeanes J, et al. Association between quantity of opioids prescribed after surgery or preoperative opioid use education with opioid consumption. JAMA 2019;321: 2465–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Syed UAM, Aleem AW, Wowkanech C, Weekes D, Freedman M, Tjoumakaris F, et al. Neer Award 2018: the effect of preoperative education on opioid consumption in patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2018;27:962–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Yajnik M, Hill JN, Hunter OO, Howard SK, Kim TE, Harrison TK, et al. Patient education and engagement in postoperative pain management decreases opioid use following knee replacement surgery. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102: 383–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Earp BE, Silver JA, Mora AN, Blazar PE. Implementing a postoperative opioid-prescribing protocol significantly reduces the total morphine milligram equivalents prescribed. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2018;100:1698–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Holt JB, Miller BJ, Callaghan JJ, Clark CR, Willenborg MD, Noiseux NO. Minimizing blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty through a multimodal approach. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Perreault RE, Fournier CA, Mattingly DA, Junghans RP, Talmo CT. Oral tranexamic acid reduces transfusions in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:2990–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Li JF, Li H, Zhao H, Wang J, Liu S, Song Y, et al. Combined use of intravenous and topical versus intravenous tranexamic acid in primary total knee and hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res 2017;12:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Yin D, Delisle J, Banica A, Senay A, Ranger P, Laflamme GY, et al. Tourniquet and closed-suction drains in total knee arthroplasty. No beneficial effects on bleeding management and knee function at a higher cost. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2017;103:583–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zhang W, Li N, Chen S, Tan Y, Al-Aidaros M, Chen L. The effects of a tourniquet used in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2014;9:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Huang Z, Xie X, Li L, Huang Q, Ma J, Shen B, et al. Intravenous and topical tranexamic acid alone are superior to tourniquet use for primary total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99:2053–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].El Bitar YF, Illingworth KD, Scaife SL, Horberg JV, Saleh KJ. Hospital length of stay following primary total knee arthroplasty: data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:1710–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Wilson JM, Farley KX, Erens GA, Guild GN 3rd. General vs spinal anesthesia for revision total knee arthroplasty: do complication rates differ? J Arthroplasty 2019;34:1417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Gao Y, Mendoza-Lattes S, Callaghan JJ. Differences in short-term complications between spinal and general anesthesia for primary total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:193–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lee QJ, Ching WY, Wong YC. Blood sparing efficacy of oral tranexamic acid in primary total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Relat Res 2017;29:57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bert JM, Hooper J, Moen S. Outpatient total joint arthroplasty. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2017;10:567–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]