Abstract

Purpose of review

Over-prescribing opioids contributes to the epidemic of drug overdoses and deaths in the United States. Opioids are commonly prescribed after childbirth especially after cesarean, the most common major surgery. This review summarizes recent literature on patterns of opioid over-prescribing and consumption after childbirth, the relationship between opioid prescribing and chronic opioid use, and interventions that can help reduce over-prescribing.

Recent findings

It is estimated that more than 80% of women fill opioid prescriptions after cesarean birth and about 54% of women after vaginal birth, although these figures vary greatly by geographical location and setting. After opioid prescriptions are filled, the median number of tablets used after cesarean is roughly 10 tablets and the majority of opioids dispensed (median 30 tablets) go unused. The quantity of opioid prescribed influences the quantity of opioid used. The risk of chronic opioid use related to opioid prescribing after birth may seem not high (annual risk: 0.12–0.65%) but the absolute number of women who are exposed to opioids after childbirth and become chronic opioid users every year is very large. Tobacco use, public insurance, and depression are associated with chronic opioid use after childbirth. The risk of chronic opioid use among women who underwent cesarean and received opioids after birth is not different from the risk of women who received opioids after vaginal delivery.

Summary

Women are commonly exposed to opioids after birth. This exposure leads to an increased risk of chronic opioid use. Physician and providers should judiciously reduce the amount of opioids prescribed after childbirth, although more research is needed to identify the optimal method to reduce opioid exposure without adversely affecting pain management.

Keywords: Childbirth, cesarean, opioid use, prescribing, postpartum

INTRODUCTION

Drug overdose is the leading cause of death for individuals younger than 50 years in the United States, and accounted for 13.1% of all deaths in 2016.1 Deaths due to opioid overdoses accounted for 66% of overdose deaths, and 40% of the opioids used in these deaths were legally prescribed.2 The social and economic ramifications are enormous. In 2015 alone, opioid overdose deaths and nonfatal expenses such as substance abuse treatment, criminal justice expenses, and lost productivity cost an estimated $504 billion.3 These estimates do not encompass other costs to society such as the rising need for foster placements due to substance use.4

Prescriptions for opioids in the United States have risen from 76 million in 1991 to 207 million in 2013.5 This dramatic rise in opioid prescriptions was paralleled with an increase in drug overdose deaths from prescription opioids and surpasses deaths related to heroin and other illegal drugs.5 The causes of this rise in prescribed opioids are multifactorial and likely include targeted marketing of specific opioids with lack of appreciation for their addictive potential, as well as widespread concern about the undertreatment of pain.6,7 In 2001, The Joint Commission published Pain Management Standards, which required organizations to establish policies regarding pain assessment and to conduct educational efforts to ensure compliance.8 Organizational attention shifted towards pain as the “fifth vital sign” and failure to treat pain as “an abrogation of a fundamental human right”.9 Some years later, we are experiencing a national opioid epidemic with enough prescriptions written annually for every adult in the United States to have a bottle of opioid tablets.10–12

Women are commonly exposed to opioids after birth. Cesarean birth is the most common major surgery in the United States, far exceeding other procedures such as knee arthroscopy or cholecystectomy.13 In 2016 alone, there were 1,258,581 cesareans performed, accounting for 32% of all births, and the majority of women received opioids at discharge from the hospital.14 Women also are prescribed opioids following vaginal birth although at a lower frequency that varies widely around the U.S. 15 Given that 86% percent of women will experience at least one birth by their mid-forties, opioid prescribing associated with childbirth potentially impacts a large proportion of American society.16 In this context, there are two major concerns: 1) excess opioid prescribing; and, 2) the risk of chronic opioid use after exposure to opioids due to childbirth.

Opioid Prescribing and Unused Opioids

Opioids are commonly prescribed after surgical procedures. While there is considerable variation in the amount of opioid prescribed by type of surgery, studies consistently document that the prescriptions are excessive as the majority of dispensed opioids remain unused.17,18,19 The frequency of patients reporting unused opioids ranges from 63% of adults undergoing outpatient upper extremity surgery20 to 86% of adults undergoing dermatologic surgery.21

Unused and accessible opioids represent a significant public health concern. In a random sampling of adults in the U.S., 20% admitted sharing opioid medications with another person, usually to help the other person manage pain.22 Similarly, of persons using prescription opioids non-medically, 55–70% obtained opioids from a family member or friend who had been prescribed opioids legitimately by a physician for a medical reason. 22–24 These data support the concern that legitimate but excessive prescribing is a major source of opioid exposure. As prescribing is a modifiable behavior, these data also imply that physicians can alter the course of this epidemic.

The Food and Drug Administration recommends returning unused opioids to a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) authorized collector or a take-back event.23 When these options are not available, opioid medications can be flushed in the toilet, but they should not be disposed of in the household trash because they are designated potentially dangerous medicines.24 In practice however, awareness and compliance with these guidelines are low. Nearly half of adults who received opioid prescriptions do not recall receiving information on safe storage or proper disposal22 and most store unused opioids in their homes in unlocked locations.17,25 Furthermore, only a small proportion of patients (3–9%) report following FDA guidelines for proper disposal. 17

Over-prescribing is also common in the obstetric population. Recent studies have documented similar patterns of opioid use among women undergoing cesarean birth.25–27 Of 165 women at a single institution who filled a prescription after cesarean birth, 75% of participants had unused tablets. The median cumulative dose used was 90 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) corresponding to 12 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg.25 Similarly, in a multicenter study of 615 women who filled an opioid prescription after cesarean, the median number of tablets used was 20 (IQR 8–30), although this figure did not adjust for opioid strength.26 In addition, these studies consistently identified other factors associated with high opioid use after childbirth including public health insurance, a history of tobacco use, and depression.25,27,28

Opioid over-prescribing is also a concern after vaginal delivery. In national samples of insured women, approximately 30% fill opioid prescriptions after routine vaginal delivery.15,28 Significant variation exists by state and geographic region with lowest fill rates in the Middle Atlantic (9.5%) and highest in the East South Central regions (46.8%).15 While prescribing rates and opioid use differ by insurance status, studies among Medicaid-enrolled women after vaginal delivery have similar findings. In Pennsylvania, 12% of women enrolled in Medicaid filled an opioid prescription after vaginal delivery29 in contrast to 53% of women enrolled in Medicaid in Tennessee during a similar time period. 30 This degree of variation is unlikely to be driven by differences in pain. Komatsu et al documented daily analgesic use after cesarean and vaginal delivery and found that 31% of women with a vaginal delivery required opioids for a short period in the hospital (<1 day) and less than 10% used opioids after discharge in comparison to 91% of women who used opioids after cesarean.31 In a study of 12,000 postpartum women at a single institution, a wide range of opioid MMEs were prescribed, which were not associated with reported pain scores. 32

Promising interventions to address opioid over-prescribing

Importantly, findings from recent studies highlight potential opportunities for intervention. Bateman et al found an association between the amount of opioid dispensed and the amount of opioid used. Compared to women in the bottom tertile of opioid dispensed (<30 tablets), women in the middle and top tertiles used significantly more opioid even after accounting for potential confounders such as pain scores, history of smoking, and labor preceding delivery (RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.10–1.65; 2.01, 95% CI 1.48–2.76).33 Ryan et al recently reported that the quantity of opioid prescribed was strongly associated with opioid used, even more so than the patient-reported pain in the week after surgery.34 Similarly, Osmundson et al found that women used about 60% of prescribed opioids regardless of opioid quantity prescribed. Among women who used all prescribed opioid, 30% reported they did so not due to pain but because they were following package labeling.25 In summary, these studies suggest that excessive quantities of opioids are commonly prescribed after birth, and that this and other prescribing-related factors influence opioid consumption more than pain. Provider education on improved prescribing aiming to reduce excessive and unnecessary opioid quantities, anticipation and discussion of expectations about having leftover tablets, as well as patient education about proper opioid use may all play a role in addressing the opioid epidemic.

Recently, several small interventions have demonstrated promise to reduce the amount of opioid prescribed and leftover. Prabhu et al enrolled 50 women who underwent cesarean delivery in a shared computer-based decision aid study that allowed women to select the number of prescribed opioids from 0 to 40 tablets. The new shared-decision process reduced the median number of opioid tablets prescribed in half, to 20 tablets compared to 40 tablets, which was the standard at the institution.35 In another study, 172 women were randomized to a standard prescription (30 tablets oxycodone 5mg) versus an individualized prescription (predicted based on inpatient opioid use). Individualized prescriptions resulted in a 50% reduction in leftover opioids (14 vs 30 tablets, p<0.001) as well as a 50% reduction in opioid used (8 vs 14 tablets, p<0.001).36 No differences in patient-reported pain outcomes were found in either study.

Opioid Prescribing, type of delivery and the Risk of Chronic Opioid Use

Exposure to opioids after surgical procedures increases the risk of chronic opioid use. Sun et al studied the association between 11 surgical procedures and chronic opioid use, defined as ≥10 filled opioid prescriptions or ≥120-day supply in months three to twelve after surgery. Seven surgeries, including cesarean delivery, were associated with chronic opioid use compared to a population of nonsurgical patients. The absolute annual risk (0.12%) and adjusted odds for chronic opioid use (aOR 1.28, 95% CI 1.12–1.46) was small compared to other surgeries such as total knee arthroplasty, (1.41%, aOR 5.10, 95% CI 4.67–5.58).37 However, given that the number of cesareans performed annually far exceeds total knee arthroplasties (1,272,000 vs 718,000), the absolute number of women at risk for chronic opioid use related to cesarean birth is potentially considerable (1,526).13

Several reasons could explain the commonly reported association between surgical procedures and chronic opioid use: persistent pain generated by its underlying cause or the surgery, characteristics of patients who undergo surgery, or the actual exposure to opioids following surgery. Some procedures such as total knee arthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty appear to be more closely associated with chronic opioid use, however these procedures are indicated to relieve pain and the procedures themselves place patients at risk for long-term pain.37 In a population-based study of 36,177 patients undergoing a variety of surgeries, there were no differences in chronic opioid use by major (i.e. bariatric surgery) versus minor surgery (i.e. varicose vein removal). Only patient characteristics were associated with chronic opioid use, but the role of the initial opioid prescriptions was not clearly addressed.38 Across multiple studies, consistent patient characteristics that appear to increase the risk for chronic opioid use have been described: female sex, tobacco use, mood disorders, and perioperative pain conditions such as back or neck pain.33,37–39 In the largest study (n=80,127 women) of chronic opioid use after cesarean, the risk of chronic use in the first year after birth ranged between 0.23% to 0.36% depending on how chronic use was defined. Persistent users were younger, more likely to use tobacco, and more likely to use benzodiazepine and antidepressant medications.33

Although prescribers cannot control patient characteristics, they control the decision to prescribe opioids, and when prescribing is warranted they control the quantity, type, and duration of opioid prescriptions.40 Studies have repeatedly reported on the association between initial opioid exposure and the risk of chronic opioid use. A previous article reported on the probability of opioid discontinuation in a longitudinal study of 1,353,902 opioid-naïve, cancer free adults. After adjustment for conditions that require pain management, initial prescribing with 90 MMEs or greater, long-acting opioids, large opioid days-supply, or co-prescribing hypnotics and muscle relaxants were independently associated with a lower likelihood of opioid discontinuation.41 In another study, the number of prescriptions filled and cumulative opioid dose dispensed during the initiation month were strongly related to the probability of long-term use.42 It is possible that patients with more severe pain filled more prescriptions and received higher dose prescriptions, although the observed associations persisted after adjusting for those patient pain characteristics.

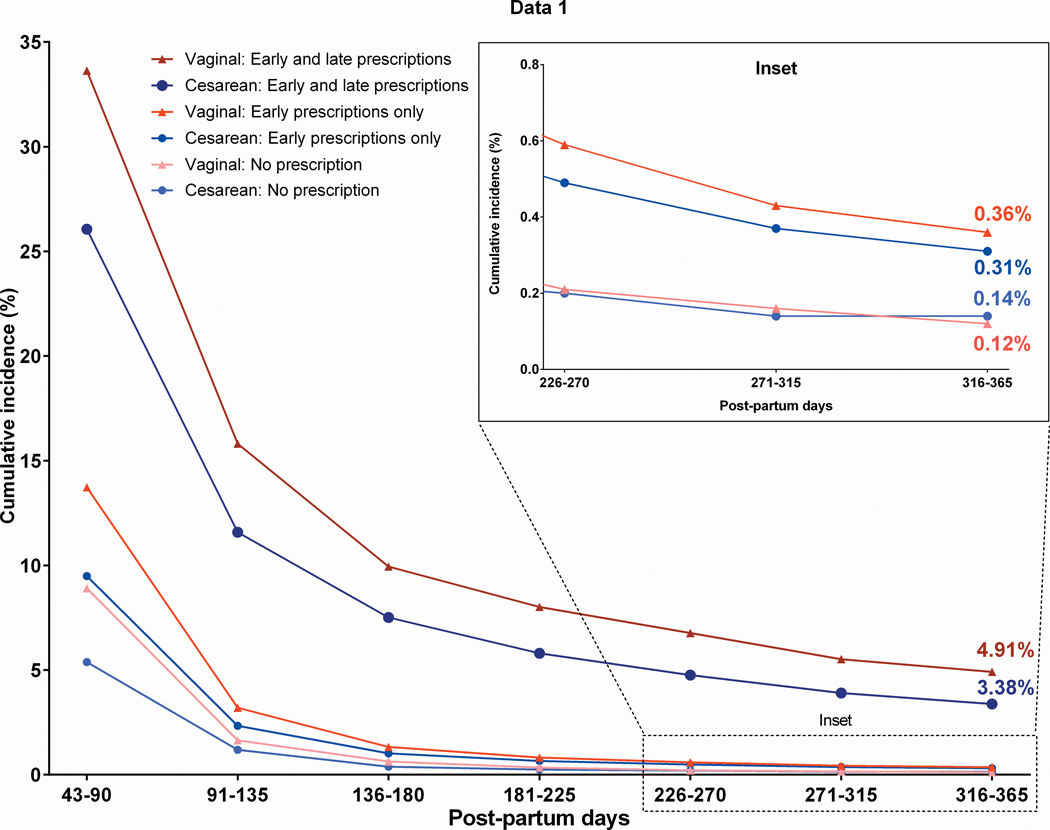

The limited studies of chronic opioid use after childbirth provide an interesting lens to examine these questions because of the intrinsic control group of women who experience the same outcome (childbirth) through different procedures (vaginal versus cesarean) and may or may not have similar exposures (opioids). While significant variability exists, time to pain and opioid free functional recovery is significant less after vaginal versus cesarean birth31 and, depending on geographical location, up to 92% of women do not receive an opioid prescription after vaginal birth.15 In a study of Tennessee Medicaid patients, the annual risk of chronic opioid use was similar among exposed women who had undergone either cesarean or vaginal delivery. Interestingly, women who required additional prescriptions in days 8–42 after delivery had the highest annual risk of chronic opioid use, but this risk was lower among women with a cesarean versus vaginal delivery (3.38% vs 4.91%, aRR 0.66, 95% CI 0.54–0.81). 30 These findings indicate that opioid exposure is associated with an increased risk for chronic opioid use, irrespective of the procedure (Figure).

Figure: Persistent opioid use at one year following delivery by postpartum prescription exposure and delivery type.

No prescription = 0 fills delivery-day 42 (n=3450 cesarean, n=33722 vaginal); Early only = ≥1 fill from delivery-day 7 and none from day 8–42 (n=21,980 cesarean, n=30,564 vaginal); Early and Late = ≥1 fill from delivery-day 7 and day 8–42 (n=5349 cesarean, n=4482 vaginal); Late only (not displayed) = 0 fill from delivery-day 7 and ≥1 fill day 8–42 (n=548 cesarean, n=2446 vaginal).

Risks of Under-Prescribing

About twenty years ago, concerns about under-treated pain initiated, in part, substantial changes in opioid prescribing practices. Today we are experiencing an epidemic of over-prescribed opioid pain relievers and its serious consequences. The proper balance for pain management likely lies somewhere in between, but finding this balance requires a comprehensive and objective re-assessment of evidence, practices and preferences. While much attention is given to the 75% of women with unused opioids after cesarean, almost one quarter of women use all prescribed opioids and are more likely to state that they receive too few opioids. 25 Under-treating pain after childbirth has significant implications for both women and their family unit. Unlike other surgeries where patients have self-paced return to activity, most women undergoing cesarean must immediately care for their newborn and other members of their family. Addressing these pain management needs requires a scrupulous assessment of the potential benefits and harms related to opioid exposure. Furthermore, whether opioids are the only pain management option requires an objective and transparent reevaluation. Several recent comparative efficacy randomized trials are building a body of evidence that challenges the dogma that opioids are better and safer than other available pain management alternatives. 43,44,45

Changing regulations and recommendations on opioid prescribing

In response to the current opioid epidemic, several regulations and laws have been issued. Thirty-four states now require that a “physical exam” be performed as the basis for prescribing an opioid.46 Twenty-three states require use of a tamper-resistant prescription form with a (non-electronic) signature from the provider.47 Furthermore, obtaining a refill for opioid prescriptions may be challenging due to laws enacted in response to the epidemic. While well-intended, these laws effectively require everyone to obtain an appointment and see a provider in order to obtain an opioid refill. This can be a substantial hardship for post-delivery convalescent women lacking access to transportation and for women caring for multiple children who might need to accompany them to such visits.

In light of increasing scrutiny over opioid prescribing, major professional medical societies and organizations have published guidelines for managing pain with opioids.24–26 These guidelines address prescribing opioids for chronic pain and managing inpatient postoperative pain, but provide little guidance for how to prescribe opioids after hospital discharge. The 2016 CDC Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, the American Pain Society Guidelines for Postoperative Pain, and the Interagency Guidelines on Prescribing Opioids for Pain provide general guidance such as not prescribing additional opioids “just in case”,11 providing discharge teaching with a plan to reduce opioids,48 and not prescribing more than a 2-week supply.49 However, none of these guidelines provide concrete recommendations for opioid prescribing after discharge. Concurrently, state legislatures have issued restrictions that may fill that gap. For example, Tennessee recently enacted legislation limiting opioid prescribing to a 3-day supply and less than 180 MME. Amounts greater than this require patients to sign an informed consent and fulfillment of certain requirements.50

CONCLUSION

Over-prescribing opioids is common and has clearly contributed to the present opioid epidemic either through excess opioids available for unwarranted use or by directly contributing to chronic opioid use. The available literature indicates that providers can prescribe less opioids without negatively impacting their patients’ pain management. Over-prescribing is common among women who undergo cesarean delivery and also among women who have vaginal deliveries. Although no formal evidence-based recommendations exist for postpartum pain management, judicious prescribing of opioids balancing potential benefits with well-known risks is strongly encouraged. Future recommendations will need to take into account not only scientific evidence on safety and efficacy of pain management alternatives, but also consider lessons from the current epidemic, such as the patients’ preference to use opioids as prescribed (e.g. use less opioids when prescribed less), the sizable fraction of women who will use all prescribed opioids and report unmet pain needs, and also factor in emerging opioid prescribing laws that may complicate prescribing for women who live far from their location of care or have limited access to healthcare due to socioeconomic factors or family demands.

The response to women with higher pain requirements or those living at a distance from birth facilities does not need to be prescribing more opioids. Interventions that individualize opioid prescribing, target women at risk for higher immediate opioid use and chronic opioid use with multimodal non-opioid therapy, or allow patients to participate in shared decision-making around the quantity of opioid dispensed demonstrate promise to reduce opioid use, opioids unused after discharge, and provide effective pain management.

KEY POINTS.

Women are commonly over-prescribed opioids after birth, and this exposure increases the risk of chronic opioid use

Over-prescribing of opioids is a modifiable target for interventions

Evidence-based recommendations/guidelines for prescribing and use of opioids after birth are urgently needed

Acknowledgements:

2. Financial Support and Sponsorship: C.G.G was supported by the National Institutes of Health - National Institute on Aging through grant R01AG043471. The funder of the study had no role in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. S.S.O was supported by K12HD04348317 from the National Institutes of Health. J.Y.M. was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations.

3. Conflicts of Interest: C.G.G has received consulting fees from Pfizer, Sanofi and Merck, and received research support from Sanofi-Pasteur, Campbell Alliance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, The Food and Drug Administration, and the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. S.S.O. has received consulting fees from Apple.

Funding

No funding was received for this work

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC Wonder. Underlying Cause of Death 1999–2016 on CDC WONDER Online Database. Underlying Cause of Death 1999–2016 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released December, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC Wonder. National Overdose Deaths from Select Prescription and Illicit Drugs. National Center on Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Council of Economic Advisers. The Underestimated Cost of the Opioid Crisis. Whitehouse. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/The%20Underestimated%20Cost%20of%20the%20Opioid%20Crisis.pdf. Published November 2017. Accessed October 2018.

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services. The Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) Report. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport24.pdf. Published November 14, 2017. Accessed 2018.

- 5.National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s Addiction to Opioids: Heroin and Prescription Drug Abuse | National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse#_ftnref4. Published July 7, 2017. Accessed July 7, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker DW. History of The Joint Commission’s Pain Standards. JAMA. 2017;317(11):1117–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porter J, Jick H. Addiction rare in patients treated with narcotics. N Engl J Med. 1980;302(2):123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanser P, Gesell S. Pain Management: The Fifth Vital Sign. Healthc Benchmarks. June 2001:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker DW. History of The Joint Commission“s Pain Standards: Lessons for Today”s Prescription Opioid Epidemic. The Joint Commission. 2017;317(11):1117–1118. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths--United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50–51):1378–1382. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in Opioid Analgesic-Prescribing Rates by Specialty, U.S., 2007–2012. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49(3):409–413. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Andrews RM. Characteristics of Operating Room Procedures in U.S. Hospitals, 2011: Statistical Brief #170. February 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(287):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.**Becker NV, Gibbins KJ, Perrone J, Maughan BC. Geographic variation in postpartum prescription opioid use: Opportunities to improve maternal safety. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2018;188:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.011.This study evaluated regional differences in opioid prescribing after uncomplicated vaginal delivery among privately-insured women. They demonstrate a 7-fold variation in prescribing rates (7.6 to 53.4%) in different regions of the U.S.

- 16.Pew Research Center. They’re Waiting Longer, but U.S. Women Today More LIkley to Have Children Than a Decade Ago. Pew Social Trends. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/01/18/theyre-waiting-longer-but-u-s-women-today-more-likely-to-have-children-than-a-decade-ago/. Published January 18, 2018. Accessed November 5, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartels K, Mayes LM, Dingmann C, Bullard KJ, Hopfer CJ, Binswanger IA. Opioid Use and Storage Patterns by Patients after Hospital Discharge following Surgery. Costigan M, ed. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0147972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim N, Matzon JL, Abboudi J, et al. A Prospective Evaluation of Opioid Utilization After Upper-Extremity Surgical Procedures. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2016;98(20):e89–e89. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel HD, Srivastava A, Patel ND, et al. A Prospective Cohort Study of Postdischarge Opioid Practices After Radical Prostatectomy: The ORIOLES Initiative. Eur Urol. October 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodgers J, Cunningham K, Fitzgerald K, Finnerty E. Opioid consumption following outpatient upper extremity surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(4):645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris K, Curtis J, Larsen B, et al. Opioid pain medication use after dermatologic surgery: a prospective observational study of 212 dermatologic surgery patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(3):317–321. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy-Hendricks A, Gielen A, McDonald E, McGinty EE, Shields W, Barry CL. Medication Sharing, Storage, and Disposal Practices for Opioid Medications Among US Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):1027–1029. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drug Enforcement Agency. Controlled Substance Public Disposal Locations. DEA Diversion Control. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Food and Drug Administration. Disposal of Unused Medicines: What You Should Know. FDA. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, Zuckerwise LC, Young JL, Richardson MG. Postdischarge Opioid Use After Cesarean Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):36–41. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.*Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of Opioid Prescription and Use After Cesarean Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):29–35. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002093.This study surveyed 720 women around the country who had undergone a cesarean delivery and found that on average half of opioids go unused. An interesting additional finding was that women dispensed higher number of opioids used more opioids.

- 27.Schmidt P, Berger MB, Day L, Swenson CW. Home opioid use following cesarean delivery: How many opioid tablets should obstetricians prescribe? J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018;44(4):723–729. doi: 10.1111/jog.13579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prabhu M, Garry EM, Hernandez-Diaz S, MacDonald SC, Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT. Frequency of Opioid Dispensing After Vaginal Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(2):459–465. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.*Jarlenski M, Bodnar LM, Kim JY, Donohue J, Krans EE, Bogen DL. Filled Prescriptions for Opioids After Vaginal Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):431–437. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001868.This retrospective cohort study of Medicaid-enrolled women found that 12% of women after vaginal delivery in Pennsylvania are prescribe an opioid. Tobacco use and a mental health condition were the only factors associated with filling a prescription

- 30.Osmundson SS, Wiese AD, Min JY, et al. Delivery Type, Opioid Prescribing, and the Risk of Persistent Opioid Use After Delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. October 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komatsu R, Carvalho B, Flood PD. Recovery after Nulliparous Birth: A Detailed Analysis of Pain Analgesia and Recovery of Function. Anesthesiology. 2017;127(4):684–694. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badreldin N, Grobman WA, Chang KT, Yee LM. Opioid prescribing patterns among postpartum women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(1):103.e1–103.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.**Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naïve women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):353.e1–353.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.016.This study used claims data from commercially insured women to examine persistent opioid use after cesarean delivery. This is one of the only studies examining specifically cesarean delivery as opposed to other surgical procedures.

- 34.Ryan H, Fry B, Gunaseelan V. Association of Opioid Prescribing With Opioid Consumption After Surgery in Michigan. JAMA Surg. October 2018:1–8. doi:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A Shared Decision-Making Intervention to Guide Opioid Prescribing After Cesarean Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):42–46. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.*Osmundson SS, Raymond BL, Kook BT, et al. Individualized Compared With Standard Postdischarge Oxycodone Prescribing After Cesarean Birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(3):624–630. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002782.This clinical trial randomized women to a standard opioid prescription (30 tablets) versus a prescription customized to a woman’s inpatient opioid use. They found that women in the customized group were not only prescribed less opioid but also used less opioid.

- 37.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286–1293. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New Persistent Opioid Use After Minor and Major Surgical Procedures in US Adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quinn PD, Hur K, Chang Z, et al. Association of Mental Health Conditions and Treatments With Long-term Opioid Analgesic Receipt Among Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(5):423–430. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.**Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of Initial Prescription Episodes and Likelihood of Long-Term Opioid Use - United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(10):265–269. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6610a1.This is a sentinel study of opioid naïve, cancer-free adults who received an opioid for pain, which found that chronic opioid use increased with increasing initial opioid prescription and use of long-acting opioids

- 41.Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Factors Influencing Long-Term Opioid Use Among Opioid Naive Patients: An Examination of Initial Prescription Characteristics and Pain Etiologies. J Pain. 2017;18(11):1374–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deyo RA, Hallvik SE, Hildebran C, et al. Association Between Initial Opioid Prescribing Patterns and Subsequent Long-Term Use Among Opioid-Naïve Patients: A Statewide Retrospective Cohort Study. J GEN INTERN MED. 2016;32(1):21–27. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3810-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of Opioid vs Nonopioid Medications on Pain-Related Function in Patients With Chronic Back Pain or Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis Pain. JAMA. 2018;319(9):872–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a Single Dose of Oral Opioid and Nonopioid Analgesics on Acute Extremity Pain in the Emergency Department. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661–1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahman NM, Pepperell J, Rehal S, et al. Effect of Opioids vs NSAIDs and Larger vs Smaller Chest Tube Size on Pain Control and Pleurodesis Efficacy Among Patients With Malignant Pleural Effusion. JAMA. 2015;314(24):2641–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.CDC. Prescription Drug Physical Examination Requirements. January 2015:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 47.CDC. Tamper-Resistant Prescription Form Requirements. May 2014:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of Postoperative Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. Journal of Pain. 2016;17(2):131–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Washington State Agency Medical Directors Group. Interagency Guideline on Prescribing Opioids for Pain. June 2015:1–105. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Together TN. Ending the Opioid Crisis. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/governorsoffice-documents/governorsoffice-documents/OpioidsPublicChapter1039.pdf. Accessed 2019.