Abstract

The oxytocin-arginine vasopressin (OT-AVP) ligand-receptor family influences a variety of physiological, behavioral, and social behavioral processes in the brain and periphery. The OT-AVP family is highly conserved in mammals, but recent discoveries have revealed remarkable diversity in OT ligands and receptors in New World Monkeys (NWMs) providing a unique opportunity to assess the effects of genetic variation on pharmacological signatures of peptide ligands. The consensus mammalian OT sequence has leucine in the 8th position (Leu8-OT), whereas a number of NWMs, including the marmoset, have proline in the 8th position (Pro8-OT) resulting in a more rigid tail structure. OT and AVP bind to OT’s cognate G-protein coupled receptor (OTR), which couples to various G-proteins (Gi/o, Gq, Gs) to stimulate diverse signaling pathways. CHO cells expressing marmoset (mOTR), titi monkey (tOTR), macaque (qOTR), or human (hOTR) OT receptors were used to compare AVP and OT analog-induced signaling. Assessment of Gq-mediated increase in intracellular calcium (Ca2+) demonstrated that AVP was less potent than OT analogs at OTRs from species whose endogenous ligand is Leu8-OT (tOTR, qOTR, hOTR), relative to Pro8-OT. Likewise, AVP-induced membrane hyperpolarization was less potent at these same OTRs. Evaluation of (Ca2+)-activated potassium (K+) channels using the inhibitors apamin, paxilline, and TRAM-34 demonstrated that both intermediate and large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels contributed to membrane hyperpolarization, with different pharmacological profiles identified for distinct ligand-receptor combinations. Understanding more fully the contributions of structure activity relationships for these peptide ligands at vasopressin and OT receptors will help guide the development of OT-mediated therapeutics.

Keywords: Arginine vasopressin, Oxytocin, Oxytocin receptor, G-protein coupled receptor, Calcium-activated potassium channel

1. Introduction

AVP and OT are synthesized in the magnocellular neurons of the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei in the hypothalamus and stored in the posterior pituitary, where they are secreted in the bloodstream and affect a number of physiological functions including maintaining water homeostasis (AVP) and stimulating parturition and lactation (OT) [1,2]. In the CNS, AVP and OT are expressed in the social brain network [3] in distinct cell populations [4,5] and are associated with opposing roles in behavioral and physiological functions [6–9]. These central AVP and OT projections are involved in social perception, cognition and decision making, and perturbations are associated with psychopathologies including autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety, and depression [6].

Evolutionary analysis reveals extreme conservation of AVP and OT in eutherian mammals which differ at amino acids 3 and 8 [10]. Vasopressin and OT are believed to have arisen from a gene duplication event prior to vertebrate divergence, whereas invertebrates generally have only one homolog [7,11]. In New World Monkeys (NWMs) AVP is conserved; however, an unusual level of OT variability has been observed with six distinct ligand variants identified to date [12–15]. OT is highly sensitive to structural modifications; small changes can affect pharmacological profiles [16–18]. Coevolution is observed for both OT and AVP ligands and their receptors [12,13,19] and subtle differences in receptor sequences between human and rat result in important alterations in the selectivity profiles of some ligands [9].

The mammalian OT-vasopressin receptor family is comprised of four G-protein coupled receptors: one canonical OT receptor and three vasopressin receptors (V1a, V1b, V2) [20]. Both OT and V1a receptors are robustly expressed in the brain [21]. Notably, there is ~85 % structural homology between OT and V1a receptors resulting in significant cross-reactivity [2,13,22–24].

The promiscuous activation of multiple G-proteins by OT receptors demonstrates some cell-specific biases [25–30]. Evolutionary factors lead to changes in ligand-receptor structure, which then may have consequences for physiological function and social behavior. Here, we assess natural variation in AVP and OT peptide ligands and OT receptors to assess ligand-receptor signaling cascades in four primate species representing ‘natural experiments’ in genetic variation in the OT receptor that are associated with phenotypic consequences: marmoset (Callithrix jacchus, Pro8-OT, NWM, socially monogamous), titi monkey (Callicebus, Leu8-OT, NWM, socially monogamous), macaque (Macaca, Leu8-OT, OWM, nonmanogamous), and human (Homo sapiens, Leu8-OT, apes, socially monogamous) [12,13]. Interestingly, binding analysis at these four OTRs demonstrated that Pro8-OT bound at modestly higher affinities than AVP or Leu8-OT, suggesting that rather than binding properties, downstream signaling pathways are primarily responsible for differences in physiological function and social behaviors [31]. We stably transfected CHO cells expressing marmoset (mOTR), titi monkey (tOTR), macaque (qOTR), and human oxytocin receptor (hOTR) and characterized AVP- and OT-analog G-protein signaling pathways by monitoring Ca2+ mobilization and membrane hyperpolarization.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell cultures

Transcriptome profiling confirmed that neuronal cell lines ND7/23, F-11 and SH-SY5Y express OT receptor [32]. Likewise, RT-PCR showed neuroblastoma cell lines SK-N-SH, SH-SY5Y, IMR-32 and astrocytoma cell line MOG-G-UVW all express OT receptor [33]. We excluded cell lines that express OT receptors from our studies inasmuch as endogenous expression would contribute to observed ligand-induced signaling. Therefore, we selected CHO cells as a common transfection background since they do not express OT receptors [34] .Wild-type Chinese hamster ovarian-K1 (CHO-K1) cells were purchased from ATCC (CCL-61) and cultured in Ham’s F12 (Hyclone SH30026.01), 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals S11550), 1.5 % HEPES 1 M Solution (Hyclone SH30231.01), 1 % Penicillin-Streptomycin (10,000 U/mL; Life Technologies 15140-163). Human oxytocin receptor (hOTR) expressing CHO-K1 cell lines were purchased from Genscript (M00195). Marmoset oxytocin receptor (mOTR) plasmid was purchased from Genscript and stably-transfected into CHO-K1 cells as described [34] CHO-K1 cells stably transfected with tOTR and qOTR as described [31] and were received from Dr. Myron Toews lab (UNMC). mOTR, tOTR, qOTR and hOTR expressing cells were cultured in Ham’s F12 (Hyclone SH30026.01), 10 % FBS (Atlanta Biologicals S11550), 1.5 % HEPES 1 M Solution (Hyclone SH30231.01), 1 % Penicillin-Streptomycin (10,000 U/mL; Life Technologies 15140-163) and 400 mg/mL G418 (RPI Corp. G64000-5.0). Human Kappa-opioid (κO) receptor expressing CHO cells (κOR – CHO) were cultured in RMPI-1640 medium supplemented with 10 % FBS (Atlanta Biologicals S11550). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in 5 % CO2 and 90 % humidity.

2.2. Drugs

AVP, Leu8-OT, and Pro8-OT Anaspec 58863 were reconstituted in DMSO Sigma-Aldrich D4540. NS-1619 Sigma-Aldrich N170, Paxilline Sigma-Aldrich P2928, SKA-31 Sigma-Aldrich S5573, thapsigargin Sigma-Aldrich T9033, and TRAM-34 Sigma-Aldrich T6700 were reconstituted in DMSO. Pertussis toxin Sigma-Aldrich P7208 was reconstituted in ultrapure water with 5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin Fisher Scientific BP1600-100. Dynorphin A (1–13) amide (American Peptide 26-4-51A) was dissolved in 25 mM Tris at pH 7.4. Apamin (Sigma-Aldrich A1289) was reconstituted in 0.05 M acetic acid.

2.3. Ca2+ mobilization assay

The effects of AVP and OT analog addition on Ca2+ mobilization were examined using Fluo3-AM fluorescence (Molecular Probes F1241) monitored with a FLIPR2 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). FLIPR operates by illuminating the bottom of a 96-well microplate with an air-cooled laser and measuring the fluorescence emissions from cell-permeant dyes in all 96 wells simultaneously using a cooled CCD camera. This instrument is equipped with an automated 96-well pipettor, which can be programmed to deliver precise quantities of solutions simultaneously to all 96 culture wells from two separate 96-well source plates.

Cells were plated at 0.3 million cells/mL in 96-well plates (MidSci P9803) and cultured overnight in culture media at 37 °C in 5 % CO2 and 95 % humidity. On the day of assay, growth medium was aspirated and replaced with 100 μl dye-loading medium per well containing 4 μM Fluo-3 AM and 0.04 % pluronic acid (Molecular Probes P3000MP) in Locke’s buffer (8.6 mM HEPES, 5.6 mM KC1, 154 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM glucose, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 2.3 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM probenecid; pH 7.4). Cells were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in 5 % CO2 and 95 % humidity and then washed four times in 180 μl fresh Locke’s buffer using an automated microplate washer (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., VT). Baseline fluorescence was recorded for 60 s, prior to a 20 μl addition of various concentrations of Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT. Cells were excited at 488 nm and Ca2+-bound Fluo-3 emission was recorded at 538 nm at 2 s intervals for an additional 200 s.

To assess the role of intracellular Ca2+ in OT-mediated mobilization of Ca2+, the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) inhibitor thapsigargin was used to deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores. Cells were incubated in 100 μl dye-loading medium per well containing 4 μM Fluo-3 AM and 0.04 % pluronic acid in Locke’s buffer (8.6 mM HEPES, 5.6 mM KC1, 154 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM glucose, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 2.3 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM probenecid; pH 7.4). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 and 95 % humidity for 60 min prior to washing four times in 180 μl Locke’s buffer and 10 μl addition of thapsigargin (1 μM final concentration) and incubated for an additional five minutes. Ca2+ mobilization assays were performed as described above.

2.4. Membrane potential assay

To assess changes in membrane potential the FLIPR Membrane Potential Assay (FMP blue; Molecular Probes F1241) was used. Cells were plated at 0.3 million cells/ml in 96-well plates (MidSci P9803) and cultured overnight in culture media at 37 °C in 5 % CO2 and 95 % humidity. Growth medium was removed and replaced with 190 μl per well of FMP Blue in Locke’s buffer (8.6 mM HEPES, 5.6 mM KCl, 154 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM glucose, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 2.3 mM CaCl2 pH 7.4). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5 % CO2 and 95 % humidity for 45 min. Baseline fluorescence was recorded for 60 s, prior to a 10 μl addition of log concentrations of AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT. Cells were excited at 530 nm and emission was recorded at 565 nm at 2 s intervals for an additional 200 s.

To assess the role of Gi/o in the OT ligand-induced membrane hyperpolarization, cells were incubated overnight with pertussis toxin (PTX) to inactivate Gi/o [35]. Cells were plated at 125,000 cells/mL in 96-well plates. PTX (150 ng/ml) was added 24 h after plating and incubated for an additional 24 h. Membrane potential assay was performed as described above. To confirm the influence of PTX on a known Gi/o mediated response, the effect of PTX on kappa-opioid receptor (κOR) mediated hyperpolarization was used as a positive control [36]. κOR — CHO were used for these experiments. The PTX assays were performed as described above for mOTR- and hOTR-expressing CHO cells, except for stimulation with dynorphin A 1–13 (DynA 1–13) rather than OT analogs.

To assess potential OT ligand-induced membrane hyperpolarization through Ca2+-activated K+ channels, we tested three inhibitors targeting Ca2+-activated K+ channel subtypes. Gq-mediated activation of protein kinase-C (PKC) causes an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ [37] with attendant activation of Ca2+ sensitive K+ channels. Ca2+-activated K+ channels are separated into three subtypes of large (BKCa), intermediate (IKca), and small conductance (SKCa) channels [38]. Paxilline is a selective inhibitor of the BKCa channel [39]. TRAM-34 is a selective inhibitor of the IK channel, KCa3.1 [40,41]. Apamin is a selective inhibitor of SKCa channels [42,43]. Cells were incubated with FMP in Locke’s buffer at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 and 95 % humidity for 35 min prior to a 10 μl addition of paxilline, TRAM-34, and/or apamin. Cells were incubated for an additional 10 min after drug addition. Membrane potential assays were performed as described above.

NS-1619 is a BKCa channel activator [44,45]. If changes in Ca2+ are responsible for activation of the BKCa, the response should be NS-1619 sensitive. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 and 95 % humidity for 35 min prior to a 10 μl addition of paxilline. Cells were incubated for an additional 10 min after paxilline addition. Membrane potential assays were performed as described above, with the exception of stimulation with NS-1619 rather than OT analogs.

SKA-31 is an activator of IKCa channel KCa3.1 [46,47]. If changes in Ca2+ are responsible for the activation of KCa3.1, the response should be SKA-31 sensitive. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 and 95 % humidity for 35 min prior to a 10 μl addition of TRAM-34. Cells were incubated for an additional 10 min after TRAM-34 addition. Membrane potential assays were performed as described above, with the exception of stimulation with SKA-31 rather than OT analogs.

To assess the role of intracellular Ca2+ in AVP and OT ligand-induced changes in membrane potential, thapsigargin was used. Cells were incubated with FMP in Locke’s buffer at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 and 95 % humidity for 40 min prior to a 10 μl addition of thapsigargin. Cells were incubated for an additional 5 min after drug addition.

2.5. Data analysis

All concentration-response data were analyzed and graphs generated using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) software. Fluo-3 relative fluorescence changes were plotted as FMAX - F0. FMAX is the maximum fluorescence achieved by the ligand. F0 is the average of the baseline fluorescence reading for 30 images (60 s). Similarly, FMP relative fluorescence changes were plotted as FMIN - F0. FMIN is the minimum fluorescence achieved by the ligand (indicative of hyperpolarization) and F0 is the average of the baseline fluorescence reading for 30 images (60 s). EC50/IC50 and EMAX values for AVP- and OT peptide-stimulated increases in Fluo-3 fluorescence or decreases in FMP Blue fluorescence were determined by nonlinear least-squares fitting of a logistic equation to the peptide concentration versus fluorescence area under the curve data. The 95 % confidence intervals for all EC50/IC50 and EMAX were used to assess differences in potency/efficacy. R2 was used to assess goodness of fit. Standard error bars have been included for all graphs; however, if the error bar is smaller than the size of the symbol, GraphPad Prism does not draw it.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of marmoset, titi monkey and macaque OTR amino acid sequence to human OTR

Significant coevolution has been shown to exist between OT ligands and receptors in NWMs [12,13]. Marmoset, titi monkey, macaque and human OT receptor amino acid sequences were accessed from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [12]. Alignment using the NCBI basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) [48] indicates that human and macaque (Macaca mulatto) OT receptor are 98 % conserved; human and titi monkey (Calicebus cupreus) OT receptor 96 % conserved; and human and marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) 94 % conserved. Physiochemical changes to marmoset, titi monkey and macaque OT receptor sequences were classified as radical when the amino acid substitution differed by size, polarity and/or charge, and conservative if the substitution did not differ by these properties (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1). Radical amino acid substitutions were primarily observed in the in the N-terminus, extracellular regions, and transmembrane regions that may play a role in ligand binding. In intracellular regions and C-terminus region, radical substitutions may affect G-protein coupling and downstream signaling. Radical changes were more numerous for mOTR with Pro8-OT as its endogenous ligand, than for tOT or qOT receptors. Amino acids 14, 51, 69, 255, and 355, in mOT, tOT and qOT receptors all differed from hOT receptor. Together, the expression of these receptors in CHO cells using a common cellular background allowed us to examine how this natural variation in ligands and receptors impacts receptor activation and cellular signaling.

Fig. 1. Comparison of marmoset, titi monkey and macaque OTR amino acid sequence to human OTR.

Identification of amino acid substitutions in marmoset (red), titi monkey (yellow), marmoset and titi monkey (red/yellow striped), macaque (blue), or all three (orange) OTRs relative to human OTR. Numbers represent the location of the amino acid substitution. Radical physiochemical substitutions that differ in size, polarity and/or charge are indicated by diamonds and amino acid substitutions that do not differ by these properties are conservative changes indicated by circles (Supplementary Table 1).

3.2. AVP and OT analogs induce Gq-mediated intracellular Ca2+ mobilization

Gq activates the phospholipase Cβ and inositol 3-phosphate signaling pathway [27] resulting in an increase in intracellular Ca2+. To compare AVP and OT analog activation of OTR-coupled Gq, we performed functional assays using the Ca2+ indicator dye Fluo3-AM. At the mOT receptor, whose endogenous ligand is Pro8-OT, AVP demonstrated a similar potency (EC50) to Pro8- and Leu8-OT, with the 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) overlapping (Fig. 2A; Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1A–C). However, the endogenous Pro8-OT was more efficacious at 1742 relative fluorescence units (RFUs) (95 % CI 1573–1912), whereas AVP was 1124 RFUs (95 % CI 1000–1248) and Leu8-OT 1372 RFUs (95 % CI 1220–1523). In the three primate receptors whose endogenous ligand is Leu8-OT (tOT, qOT, and hOT receptors), AVP was less potent and efficacious than either OT analog (Fig. 2B–D; Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1D–L). In tOT receptor cell lines, AVP was 33X less potent than Leu8-OT and 13X less potent than Pro8-OT (Table 1). Leu8-OT 2710 RFUs (95 % CI 2424–2996) displayed equivalent efficacy with Pro8-OT 2779 RFUs (95 % CI 2485–3047), whereas AVP was less efficacious 2198 RFUs (95 % CI 2014–2382). In qOT receptor cell lines, AVP was 5X less potent than Leu8-OT and 8X less potent than Pro8-OT (Table 1). Likewise, Leu8-OT 4089 RFUs (95 % CI 3585–4594) displayed similar efficacy to Pro8-OT 3386 RFUs (95 % CI 2955–3816), but was more efficacious than AVP 2775 RFUs (95 % CI 2608 to 2942). In hOT receptor cell lines, AVP was 9X less potent than Leu8-OT and 16X less potent than Pro8-OT (Table 1). Leu8-OT 3867 RFUs (95 % CI 3473–4293) displayed similar effiicacy to Pro8-OT 3483 RFUs (95 % CI 3075–3890), but was more efficacious than AVP 3150 RFUs (95 % CI 2787–3441). AVP, Leu8-OT, and Pro8-OT did not elevate intracellular Ca2+ in non-transfected CHO-K1 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). These data demonstrate that the dose-dependent responses observed in OTR-expressing lines is attributable to OTR expression.

Fig. 2. AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT induced calcium mobilization in mOTR-, tOTR-, qOTR-, or hOTR-expressing CHO cells.

AVP, Leu8-OT, and Pro8-OT concentration-response relationships in mOTR cells (A), in tOTR cells (B), in qOTR cells (C), and in hOTR cells (D). AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT analogs were run in parallel on the same plates, at the same time, with the same split of cells. N = 3 experiments (3–4 replicates per dose per experiment). Time-response (Supplementary Fig. 1). Statistical analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

AVP and OT-analog induced intracellular calcium mobilization.

| Ligand (nM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Line | Parameter | AVP | Leu8-OT | Pro8-OT |

| mOTR | EC50 | 2.00 | 1.61 | 0.44 |

| 95 % CI | 0.63 to 6.32 | 0.61 to 5.13 | 0.14 to 1.40 | |

| R2 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.70 | |

| tOTR | EC50 | 63.26 | 1.87 | 4.68 |

| 95 % CI | 42.69 to 93.75 | 0.72 to 4.84 | 2.05 to 10.72 | |

| R2 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 0.91 | |

| qOTR | EC50 | 49.78 | 10.61 | 5.95 |

| 95 % CI | 36.78 to 67.38 | 4.57 to 24.19 | 2.41 to 14.67 | |

| R2 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.89 | |

| hOTR | EC50 | 98.63 | 11.02 | 5.58 |

| 95 % CI | 62.23 to 153.00 | 5.18 to 23.48 | 2.45 to 12.72 | |

| R2 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.91 | |

Potency of AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT at inducing calcium mobilization in mOTR, tOTR, qOTR and hOTR CHO cells. N = 3 experiments (3–4 replicates per dose per experiment). Sigmoidal curves (Fig. 2).

Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) maintains the Ca2+ gradient between the cytosol and endoplasmic reticulum, and therefore SERCA pump inhibition results in depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores [49,50]. To confirm the role of intracellular Ca2+ stores in AVP- and OT-analog mediated Ca2+ influx, cells were pretreated with thapsigargin, a potent SERCA inhibitor. We pretreated all four lines with thapsigargin and evaluated AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT induced Ca2+ influx. In control assays AVP and OT analogs produced concentration-dependent increases in Ca2+; however, pretreatment with thapsigargin blocked AVP and OT-analog evoked increases in Ca2+ (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. 3) [34] demonstrating the dependence on intracellular Ca2+ stores.

Fig. 3. Effects of pretreatment with thapsigargin (Tg) on AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT induced changes on intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in mOTR-, hOTR-, tOTR-, and qOTR-expressing CHO cells.

Control AVP and Tg-pretreated concentration response relationships in mOTR-expressing cells (A), in hOTR-expressing cells (B), in tOTR-expressing cells (C), in qOTR-expressing cells (D). Leu8-OT and Tg-pretreated concentration response relationships in tOTR-expressing cells (E) and qOTR-expressing cells (F). Pro8-OT and Tg-pretreated concentration response relationships in tOTR-expressing cells (G) and qOTR-expressing cells (H). Control and Tg-pretreated replicates were run in parallel on the same plates, at the same time and with the same split of cells. N = 3 experiments (five replicates per dose per experiment). Time response (Supplementary Fig. 3).

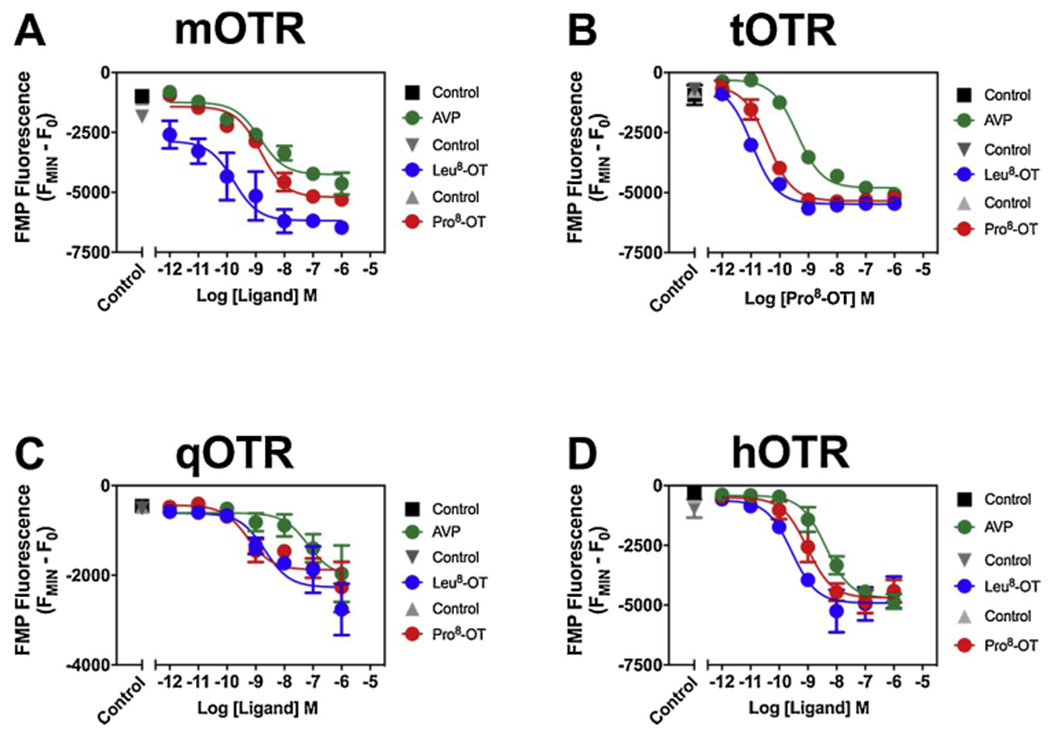

3.3. AVP and OT analog-induced changes in membrane potential are dependent on gq mediated Ca2+ mobilization

To assess the role of AVP and OT-induced membrane hyperpolarization, we performed functional assays using FMP blue, a membrane potential-sensitive dye that displays increased fluorescence in response to depolarization and decreased fluorescence in response to membrane hyperpolarization [51,52]. Membrane hyperpolarization can be influenced by numerous ion channels, including Gi/o activation of GIRK channels and Gq activation of calcium-activated potassium channels [34]. Thus, potential ligand bias [53], and the potential for activation of multiple pathways suggest these data may be different from the Fluo-3 assays. In cell lines for all four OT receptors, AVP and both OT-analogs produced concentration-dependent decreases in FMP blue fluorescence consistent with a hyperpolarizing response (Fig. 4; Table 2; Supplementary Fig. 4). In mOT receptor cell lines, the 95 % confidence intervals for potency for all three ligands overlapped (Fig. 4A; Table 2; Supplementary Fig. 4A–C) However, Leu8-OT 6185 (95 % CI 5479–6891) and Pro8-OT 5207 RFUs (95 % CI 4862–5553), were more efficacious than AVP 4264 RFUs (95 % CI 3869–1659). In tOT and hOT receptor cell lines, Leu8-OT was 4x more potent than Pro8-OT, and Pro8-OT was more potent than AVP by ~10X and ~4X, respectively (Fig. 4B,D; Table 2; Supplementary Fig. 4D–F, J–L). In tOT receptor expressing cells, Leu8-OT 5477 (95 % CI 5149–5805) and Pro8-OT 5347 RFUs (95 % CI 5094–5600), were more efficacious than AVP 4803 RFUs (95 % CI 4575–5031). In hOT receptor expressing cells, there was no substantial difference in efficacy with AVP 5049 RFU (95 % CI 4817–5281), Leu8-OT 5064 (95 % CI 4787–5341) and Pro8-OT 5303 RFUs (95 % CI 4970–5635). In qOT receptor cell lines, no significant difference was observed between Pro8-OT and Leu8-OT, but Leu8-OT was 30X more potent than AVP (Fig. 4C; Table 2; Supplementary Fig. 4G–I). However, the 95 % CI of efficacies for all three ligands overlapped, with AVP 2033 RFU (95 % CI 1310–2755), Leu8-OT 2268 (95 % CI 1827–2709) and Pro8-OT 1878 RFUs (95 % CI 1586–2170).The absence of effects on membrane potential in untransfected CHO-K1 cells demonstrated the requirement for OTR transfection in the observed hyperpolarizing response to AVP (Supplementary Fig. 5), Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT [34]. Together, AVP is more potent at OTRs from marmoset with Pro8-OT as its endogenous ligand, than species whose cognate ligand is Leu8-OT.

Fig. 4. AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT induced changes in membrane potential in mOTR-, tOTR-, qOTR-, or hOTR-expressing CHO cells.

AVP, Leu8-OT, and Pro8-OT concentration-response relationships in mOTR cells (A), in tOTR cells (B), in qOTR cells (C), in hOTR cells (D). AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT analogs were run in parallel on the same plates, at the same time, with the same split of cells. N = 3 experiments (3–1 replicates per dose per experiment). Time response (Supplementary Fig. 4). Statistical analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

AVP and OT-analog induced membrane hyperpolarization.

| Ligand | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Line | Parameter | AVP | Leu8-OT | Pro8-OT |

| mOTR | IC50 | 1.41 nM | 0.17 nM | 1.49 nM |

| 95 % CI | 0.57 to 3.50 | 0.03 to 1.03 | 0.79 to 2.81 | |

| R2 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 0.9 | |

| tOTR | IC50 | 0.4 nM | 10.83 pM | 38.60 pM |

| 95 % CI | 0.27 to 0.61 | 5.08 to 23.09 | 22.56 to 66.05 | |

| R2 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.91 | |

| qOTR | IC50 | 59.46 nM | 1.83 nM | 0.53 nM |

| 95 % CI | 8.17 to 432.60 | 0.36 to 9.27 | 0.14 to 2.09 | |

| R2 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 0.68 | |

| hOTR | IC50 | 4.20 nM | 0.27 nM | 0.95 nM |

| 95 % CI | 2.24 to 8.03 | 0.09 to 0.89 | 0.40 to 2.20 | |

| R2 | 0.90 | 0.70 | 0.82 | |

Potency of AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT at inducing membrane hyperpolarization in mOTR, tOTR, qOTR and hOTR CHO cells. N = 3 experiments (3–4 replicates per dose per experiment). Sigmoidal curves (Fig. 3).

Pertussis toxin catalyzes ADP-ribosylation of the Gαi/o subunit [54], locking Gi/o in its GDP-bound inactive state and preventing the pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein from interacting with a GPCR. To assess the role of Gi/o in AVP and OT-analog induced hyperpolarization, we pretreated cells with pertussis toxin. In mOT receptor CHO cells we previously demonstrated Leu8-OT mediated hyperpolarization was partially sensitive to pertussis toxin, suggesting both Gi-mediated and pertussis toxin-insensitive pathways contribute to the hyperpolarizing response [34]. Pertussis toxin treatment did not inhibit AVP induced hyperpolarization in any of the four cell lines (Fig. 5A–D; Supplementary Fig. 6A–H; Supplementary Table 2), Leu8-OT induced hyperpolarization in tOT or qOT receptor cell lines (Fig. 5E–F; Supplementary Fig. 6I–L, Supplementary Table 2), or Pro8-OT induced hyperpolarization in in tOT or qOT receptor cell lines (Fig. 5G–H; Supplementary Fig. 6M–P, Supplementary Table 2), suggesting that Gi/o does not contribute to the hyperpolarizing response for these ligand-receptor combinations [34]. Given that the kappa-opioid (κO) receptor couples to Gi, we used a κOR expressing CHO cell line (κOR – CHO) as a positive control to demonstrate pertussis toxin’s ability to disrupt Gi. DynorphinA1-13-NH2, a κO receptor agonist, produced a robust hyperpolarizing response in control κO receptor cell lines, that was abolished in cells pretreated with pertussis toxin (Supplementary Figure 7). These data support our conclusion that AVP and OT analog-induced hyperpolarization in OTR-expressing cells do not involve the pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins, Gi/o.

Fig. 5. Lack of effect for pretreatment with PTX on AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT induced changes in membrane potential in mOTR-, tOTR-, qOTR- and hOTR-expressing CHO cells.

Control AVP and PTX-pretreated concentration response relationships in mOTR-expressing cells (A), in hOTR-expressing cells (B), in tOTR-expressing cells (C), in qOTR-expressing cells (D). Leu8-OT and PTX-pretreated concentration response relationships in tOTRexpressing cells (E) and qOTR-expressing cells (F). Pro8-OT and PTX-pretreated concentration response relationships in tOTR-expressing cells (G) and qOTR-expressing cells (H). Control and PTX-pretreated replicates were run in parallel on the same plates, at the same time and with the same split of cells. N = 3 experiments (five replicates per dose per experiment). Time-response (Supplementary Fig. 6). Statistical analysis (Supplementary Table 2).

OT analog induced hyperpolarization involves mOT and hOT receptors coupling to Gq activating the Gq/phosphoinositide-phopsholipase C pathway and Ca2+-dependent K+ channel activation [34]. To explore the role of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in AVP-induced changes in membrane potential, as well as extending our data with OT analogs in tOT and qOT receptors, we used a pharmacological approach with inhibitors that discriminate between subtypes of Ca2+-activated K+ channels. There are three subtypes of Ca2+-activated K+ channels, including small conductance (SKCa), intermediate conductance (IKCa) and large conductance (BKCa) channels [38]. To assess the role of SKCa channels in AVP and OT-mediated membrane hyperpolarization cells were pretreated with the SKCa-selective blocker apamin, which blocks SKCa channels through an allosteric mechanism [43]. In mOT and hOT receptor CHO cells, we previously observed no major contribution (≤ 15 %) on Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT induced membrane hyperpolarization after pretreatment with apamin [34]. Similarly, in all four cell lines, apamin did not significantly affect AVP-induced changes in membrane potential (Fig. 6A–D; Supplementary Figures 8A–B, 9A, 10A; Supplementary Table 3). Likewise, in tOT and qOT receptor CHO cells, we observed no substantial effects (≤ 15 %) of pretreatment with apamin on Leu8-OT or Pro8-OT induced membrane hyperpolarization (Fig. 6E–H; Supplementary Figures 9B–C, 10B–C; Supplementary Table 3). Together, these data suggest that SKCa channels provide little or no contribution to AVP and OT mediated changes in membrane potential across these four primate OTRs.

Fig. 6. Effects of pretreatment with Ca2+-activated K+ inhibitors on AVP and/or Leu8-OT or Pro8-OT induced changes in membrane potential in mOTR-, hOTR-, tOTR-, and qOTR-expressing CHO cells.

Inhibitor fluorescence was normalized to AVP (A-D), Leu8-OT (E-F), or Pro8-OT-induced (G-H) membrane hyperpolarization. Time response (Supplementary Figures 8–10). Area under the curve (negative peaks only) were assessed and a one-way Anova was performed with Sidek’s multiple comparisons to determine statistical significance. N = 3 experiments for each inhibitor/analog/cell line combination (10 replicates per dose per experiment). Adjusted p-values (Supplementary Table 3).’.

To assess the roles of BKCa channels in AVP and OT-analog mediated changes in membrane potential, cells were pretreated with the BKCa blocker paxilline, which stabilizes the channel in its closed conformation [55]. In mOT receptor CHO cells, paxilline produced a moderate inhibition of AVP induced hyperpolarization, resulting in a 20 % inhibition (Fig. 6A; Supplementary Figure 8C, Supplementary Table 3) and produced greater inhibition (52 %) in hOT receptor cells (Fig. 6B; Supplementary Figure 8D, Supplementary Table 3). In tOT receptor CHO cells, paxilline produced minimal inhibition in AVP and moderate inhibition in Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT induced changes in membrane potential, resulting in a 13 %, 38 % and 39 % reduction of the hyperpolarizing response, respectively (Fig. 6C,E,G; Supplementary Figure 9D–F; Supplementary Table 3). In qOT receptor CHO cells, paxilline produced a moderate inhibition in AVP and Pro8-OT induced changes in membrane potential and substantial inhibition in Leu8-OT, resulting in a 20 % 35 % and 46 % inhibition, respectively (Fig. 6D,F,H; Supplementary Figure 10D–F; Supplementary Table 3). Together, these data suggest that BKCa channels contribute to a fraction of the AVP and OT-analog induced changes in membrane potential. In mOT and hOT receptor CHO cells, the BKCa activator NS-1619 is inhibited with paxilline [34]. Here we challenged tOT and qOT receptor CHO cells with NS-1619, and the evoked hyperpolarization was blocked with 30 μM paxilline by 80 % and 72 %, respectively (Supplementary Figure 11 A–B,E–F; Supplementary Table 4) supporting a role for BKCa channels in the regulation of CHO cell membrane potential.

To assess the role of IKCa channels in AVP and OT-mediated membrane hyperpolarization, cells were pretreated with TRAM-34, an IKCa channel blocker that specifically blocks KCa3.1 by occupying the K+ binding site [40]. TRAM-34 produced the most effective inhibition in AVP and OT-analog mediated changes in membrane potential, with AVP less impacted than OT analogs in three OT receptor species (mOT, tOT, and hOT receptor). In mOT receptor CHO cells, TRAM-34 produced a moderate inhibition in AVP-induced membrane potential (33 %; Fig. 6A; Supplementary Figure 8E; Supplementary Table 3). In hOT receptor CHO cells, TRAM-34 produced a more robust inhibition of AVP-induced membrane potential (61 %; Fig. 6B; Supplementary Figure 8 F; Supplementary Table 3). In tOT receptor CHO cells, TRAM- 34 produced a moderate inhibition in AVP-induced membrane potential (25 %), whereas Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT were inhibited somewhat greater, 38 % and 37 %, respectively (Fig. 6C,E,G; Supplementary Figure 9G–I; Supplementary Table 3). In qOT receptor CHO cells, AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT were robustly inhibited, ~98 % each (Fig. 6D,F,H; Supplementary Figure 10G–I; Supplementary Table 3). Involvement of KCa3.1 in hyperpolarization can be tested with the activator SKA-31. We challenged tOT and qOT receptor CHO cells with SKA-31 and showed that the hyperpolarization was inhibited by 300 nM TRAM-34 pretreatment by 78 % and 92 %, respectively (Supplementary Figure 11C–D, G–H; Supplementary Table 4). These results support the role for the KCa3.1 channel in the regulation of membrane potential by AVP and OT-ligands.

To determine the combined contribution of BKCa and KCa3.1 channels in AVP and OT-mediated changes in membrane potential, cells were pretreated with both paxilline and TRAM-34. In mOT receptor CHO cells, the combined exposure of paxilline and TRAM-34 inhibited AVP-induced membrane hyperpolarization by 91 % (Fig. 6A; Supplementary Figure 8 G; Supplementary Table 3). In hOT receptor CHO cells, the combined exposure of paxilline and TRAM-34 inhibited AVP-induced hyperpolarization by 87 % (Fig. 6B; Supplementary Figure 8 H; Supplementary Table 3). In tOT receptor CHO cells, paxilline and TRAM-34 combined inhibited AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT by 57 %, 40 % and 60 % (Fig. 6C,E,G; Supplementary Figure 9J–L; Supplementary Table 3). In qOT receptor CHO cells, the combination completely inhibited AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT induced hyperpolarization (Fig. 6D,F,H; Supplemmentary Figure 10J–L; Supplementary Table 3). Together, these data indicated an additive effect of inhibition of BKCa and KCa3.1 channels demonstrating that they are primarily responsible for AVP and OT-analog induced membrane hyperpolarization in CHO cells expressing these OTRs.

To confirm the role of intracellular Ca2+ stores in AVP- and OT analog mediated membrane hyperpolarization, cells were pretreated with the SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin to [49,50]. As expected, pretreatment with thapsigargin eliminated the hyperpolarization produced by AVP, Leu8-OT, and Pro8-OT in at all four OT receptor cell lines (Supplementary Figure 12) [34]. Together, these data demonstrated that intracellular Ca2+ stores are the source of Ca2+ responsible for AVP and OT-analog engagement of K+ channels. Interestingly, in thapsigargin pretreated tOT and hO receptor CHO cells challenged with Leu8-OT, and in hOT receptor cells challenged with Pro8-OT a depolarizing response was observed (Supplemetary Figure 12E) [34] indicating a possible dual modulation of K+ channel currents by OT analogs through these OT receptors.

4. Discussion

The molecular structure of OT-AVP family peptides and receptors, as well as a facilitation of physiological responses and social behaviors related to stress and anxiety are highly conserved in evolution [2,7,8,11,13]. One mechanism to assess genetic conservation is quantification via the ratios of nonsynomous nucleotide substitutions relative to synonymous substitutions (dN/dS), where ratios less than 1.0 imply stabilizing selection and greater than 1.0 selection for diverse sequences. Analysis of dN/dS ratios for AVP is 0.005 and OT is 0.009, suggesting extreme conservation for both peptides [10]. Comparison of OT analogs across NWM suggests positions 2 and 8 are most variable [56], with a single amino acid substitution at the 8th position causing in a Leu > Pro change resulting in a rigid turn in the peptide backbone [12,15]. Moreover, genetic changes in ligand structure resulted in a significantly higher proportion of corresponding changes in the OT receptor sequences of NWMs, particularly at the N-terminus which is involved in ligand binding [12], as is evident in the greater number of mOT receptor substitutions (red) with Pro8-OT as its endogenous ligand as compared to tOT receptor (yellow) or qOT receptor (blue) substitutions that have the consensus mammalian Leu8-OT as their endogenous neuropeptide (Fig. 1). These changes likely affect the overall three dimensional architecture of the receptor, each of which may contribute to differences in cellular signaling.The natural variability within OT-AVP family in NWMs provides a unique opportunity to assess these signaling cascades in relation to ligand-receptor coevolution [12,57], particularly in relation to social behaviors. For example, social monogamy is exceptionally high in NWMs and phylogeny correlated statistical comparisons demonstrate it corresponds with ligand-receptor coevolution [12] , whereas social monogamy is rare among mammals in general [13]. Both OT analogs have been shown to modulate social behavior in marmosets, with the cognate ligand Pro8-OT more effective than Leu8-OT in relation to sexual fidelity and reduced prosocial behaviors towards strangers [58,59].

At the cellular level, ligand and receptor structure, as well as cellular context, appear to influence how GPCRs activate downstream signaling cascades. These signaling cascades result in changes in cell function, influencing physiological and behavioral effects at the organismal level [60]. A recent study assessed the binding properties for these ligands at the OTRs and found that the rank order affinity was Pro8-OT > Leu8-OT > AVP for receptors from all four species [31]. We recognize the importance of cellular context in GPCR signaling and understand that signaling profiles in the heterologous expression system (CHO cells) that we selected may differ from those of intact neurons. However, primary neuronal cultures from expressing the OT receptors from the species we are evaluating are not currently available. Established human neuroblastoma and glioma cell lines reportedly express the endogenous hOT receptor [33], although these cells do not successfully recapitulate the sensitivity of primary neurons in culture [61] and therefore signaling profiles may also differ from intact primary neuronal cultures. Thus, we believe that these initial in vitro experiments to define the signaling profiles of AVP and OT variants are a fundamental first step to understanding ligand-receptor function.

In this study we compared the pharmacological signatures of AVP, Leu8-OT, and Pro8-OT in CHO cells expressing marmoset, titi monkey, macaque, or human OT receptors. Our results confirm that all three ligands activated Gq signaling in concentration-dependent increases in intracellular Ca2+ through all four OT receptors. Interestingly, at OT receptors with Leu8-OT as their endogenous ligand (titi monkey, macaque, human) AVP was less potent and efficacious than OT analogs. In contrast, at the mOT receptor, with Pro8-OT is the cognate ligand, AVP potency comparable to OT analogs. Notably, Pro8-OT was more efficacious than AVP or Leu8-OT, suggesting evolutionary differences in receptor structure may play a role in ligand potency and efficacy at the OTR [12,13]. We confirmed the role of intracellular Ca2+ in AVP and OT analog-induced Ca2+ mobilization at all four OT receptors by depleting intracellular Ca2+ with thapsigargin, which inhibited the response to all three ligands [34].

Given the promiscuous coupling of OTRs to various G-proteins [28,29], we next assessed the ability of AVP, Leu8-OT, and Pro8-OT to trigger a hyperpolarizing response at the four OT receptors. AVP was less potent than either OT analog at the three OT receptors whose cognate ligand is Leu8-OT. However, at the mOT receptor, no significant differences were observed in the potency of AVP and Pro8-OT. Leu8-OT was more potent at the mOT, tOT and hOT receptors, whereas Pro8-OT was appeared slightly more potent at the qOT receptor. Notably, AVP was less efficacious at mOT and tOT receptors (both NWMs), whereas no differences in efficacy were observed for the three ligands at qOT receptor (an OWM) or hOT receptor, suggesting common nucleotide substitutions in the in mOT and tOT receptor may contribute to observed differences in ligand efficacy.

GPCR coupling to Gi/o stimulates G-protein-gated inward rectifying K+ channels via the Gβγ subunit [62]. Pertussis toxin inhibits Gi/o from coupling to the GPCR [63] thus blocking Gi/o protein mediated contribution to the hyperpolarizing response. Our previous data demonstrated that Gi/o is responsible for a minor portion of the Leu8-OT induced hyperpolarizing response at the mOT receptor, suggesting a dual modulation by a pertussis toxin-sensitive and pertussis toxin-insensitive G-proteins (Pierce et al. 2019). The Leu8-OT induced hyperpolarizing response was pertussis toxin-insensitive in OTRs from all three species whose cognate ligand is Leu8-OT. Both AVP and Pro8-OT are pertussis toxin-insensitive at all four OT receptors, suggesting Gi/o coupling does not contribute to their hyperpolarizing response. Since these in vitro analyses all utilize the same CHO-K1 cell line, cellular context is unlikely to be a contributing factor.

Since AVP and OT-ligand induced membrane hyperpolarization are largely pertussis toxin-insensitive, we assessed the contribution of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in AVP and OT-analog mediated hyperpolarization using channel blockers specific for SKCa, BKCa (KCa1.1), and IKCa (KCa3.1). Apamin selectively blocks SKCa channels, and pretreatment with this inhibitor resulted in minimal or no inhibition (≤ 15 %) of AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT at the mOT, tOT, qOT and hOT receptors. These data demonstrate that SKCa channels provide minimal contribution to AVP and OT-analog induced membrane hyperpolarization. Paxilline is a selective blocker of BKCa channels, which contributes to neuronal excitability [64]. Pretreatment with paxilline resulted in partial inhibition for AVP and OT analogs in cells expressing each of the four OT receptors. This is consistent with previous reports that Leu8-OT mediated hyperpolarization through OT receptor Gq/phosphoinositide-phopsholipase C pathway activation of BKCa channels [34,65]. Paxilline also inhibited the hyperpolarizing response to the BKCa channel opener NS-1619 in mOT, hOT [34], tOT and qOT receptor CHO cells, further supporting the role for BKCa channels in membrane hyperpolarization. TRAM-34 selectively inhibits a IKCa channel (KCa3.1) [40], and also regulates neuronal excitability [66]. Pretreatment with TRAM-34 produced the most robust inhibition of the hyperpolarizing response to all three ligands in cell lines expressing each of the four OT receptors. TRAM-34 also inhibited membrane the hyperpolarizing response to KCa3.1 channel opener SKA31 in mOT, hOT [34], tOT and qOT receptor CHO cells, demonstrating the involvement of KCa3.1 in membrane hyperpolarization. Combined pretreatment with paxilline and TRAM-34 suggested that OT receptor Gq/phosphoinositide-phopsholipase C pathway activation of BKCa and the IKCa channel KCa3.1 were additive. Depletion of intracellular Ca2+ with SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin confirmed the role of intracellular Ca2+ stores in AVP and OT-ligand induced membrane hyperpolarization in the OT receptor-Gq/phosphoinositide-phopsholipase C pathway activation of Ca2+ dependent K+ channels.

The OT-AVP family of neuropeptides and receptors plays a fundamental role in mediating physiological processes and social behaviors [67–70], with perturbations associated with various social and behavioral deficits [6]. These sociobehavioral functions prompt interest in OT as a potential therapeutic mediator in conditions such as autism spectrum disorder [71], depression and anxiety [6,72], schizophrenia [73,74], and post-traumatic stress disorder [75]. Clinically, OT is used peripherally to induce labor [76] and prevent postpartum hemorrhage [77], which provide further therapeutic potential for OT analogs. A major challenge is connecting ligand-induced receptor activation at the cellular level to changes in organismal physiological and behavioral functions [60]. The present results show that AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT display functionally distinct responses at the various OTRs examined. Some of these differences correspond to cognate ligand and receptor structure, such as OT-analogs increased potency at inducing membrane hyperpolarization and intracellular Ca2+ mobilization compared to AVP at the OTRs from species whose cognate ligand is Leu8-OT. The unique diversity of OT ligands and receptors in NWMs provide a natural experiment whereby we can begin to parse out how pharmacological profiles are affected by ligand and receptor structure, and how these correlate with specific behavioral outcomes, providing insight for the advancement of OT-mediated therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Aknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [Grant R01HD089147]. We thank Dr. Myron Toews, Nancy Schulte and Dr. Jack Taylor for providing the stably transfected qOTR and tOTR cell lines. We thank Dr. Jeffrey French and Dr. Aaryn Mustoe for providing the AVP, Leu8-OT and Pro8-OT peptides. We thank Dr. Aaryn Mustoe for helping with some of the experiments. We thank Dr. Suneet Mehrotra for his thoughtful discussions and Ms. Bridget Sefranek for her careful reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- AVP

arginine vasopressin

- BKCa

large conductance calcium-activated potassium channel

- BLAST

basic local alignment search tool

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- Ca2+

calcium

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- CI

confidence interval

- CNS

central nervous system

- EC50

half-maximal response

- EMAX

maximum response achievable

- FMP

FLIPR membrane potential

- GIRKs

G-protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- hOTR

hOT receptor human oxytocin receptor

- IC50

concentration producing 50 % inhibitory response

- IKCa

intermediate conductance calcium-activated potassium channel

- Leu8-OT

consensus mammalian oxytocin sequence

- mOTR

mOT receptor marmoset oxytocin receptor

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NWM

new world monkeys

- OT

oxytocin

- OTR

oxytocin receptor

- K+

potassium

- OWM

old world monkeys

- Pro8-OT

oxytocin sequence with proline in 8th position

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- qOTR

qOT receptor macaque oxytocin receptor

- SERCA

sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase

- SKCa

small conductance calcium-activated potassium channel

- Tg

thapsigargin

- tOTR

tOT receptor, titi monkey oxytocin receptor

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109832.

References

- [1].Ludwig M, Leng G, Dendritic peptide release and peptide-dependent behaviours, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 7 (2) (2006) 126–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jurek B, Neumann ID, The oxytocin receptor: from intracellular signaling to behavior, Physiol. Rev 98 (3) (2018) 1805–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Newman SW, The medial extended amygdala in male reproductive behavior. A node in the mammalian social behavior network, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 877 (1999) 242–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Huber D, Veinante P, Stoop R, Vasopressin and oxytocin excite distinct neuronal populations in the central amygdala, Science 308 (5719) (2005) 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gainer H, Cell-type specific expression of oxytocin and vasopressin genes: an experimental odyssey, J. Neuroendocrinol 24 (4) (2012) 528–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Neumann ID, Landgraf R, Balance of brain oxytocin and vasopressin: implications for anxiety, depression, and social behaviors, Trends Neurosci. 35 (11) (2012) 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Stoop R, Neuromodulation by oxytocin and vasopressin, Neuron 76 (1) (2012) 142–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stoop R, Neuromodulation by oxytocin and vasopressin in the central nervous system as a basis for their rapid behavioral effects, Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 29 (2014) 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chini B, Manning M, Agonist selectivity in the oxytocin/vasopressin receptor family: new insights and challenges, Biochem. Soc. Trans 35 (Pt 4) (2007) 737–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wallis M, Molecular evolution of the neurohypophysial hormone precursors in mammals: comparative genomics reveals novel mammalian oxytocin and vasopressin analogues, Gen. Comp. Endocrinol 179 (2) (2012) 313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Donaldson ZR, Young LJ, Oxytocin, vasopressin, and the neurogenetics of sociality, Science 322 (5903) (2008) 900–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ren D, Lu G, Moriyama H, Mustoe AC, Harrison ER, French JA, Genetic diversity in oxytocin ligands and receptors in New World monkeys, PLoS One 10 (5) (2015) e0125775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].French JA, Taylor JH, Mustoe AC, Cavanaugh J, Neuropeptide diversity and the regulation of social behavior in New World primates, Front. Neuroendocrinol 42 (2016) 18–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vargas-Pinilla P, Paixao-Cortes VR, Pare P, Tovo-Rodrigues L, Vieira CM, Xavier A, Comas D, Pissinatti A, Sinigaglia M, Rigo MM, Vieira GF, Lucion AB, Salzano FM, Bortolini MC, Evolutionary pattern in the OXT-OXTR system in primates: coevolution and positive selection footprints, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112 (1) (2015) 88–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee AG, Cool DR, Grunwald WC Jr., Neal DE, Buckmaster CL, Cheng MY, Hyde SA, Lyons DM, Parker KJ, A novel form of oxytocin in New World monkeys. Biol. Lett 7 (4) (2011) 584–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Beard R, Stucki A, Schmitt M, Py G, Grundschober C, Gee AD, Tate EW, Building bridges for highly selective, potent and stable oxytocin and vasopressin analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem 26 (11) (2018) 3039–3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sciabola S, Goetz GH, Rai G, Rogers BN, Gray DL, Duplantier A, Fonseca KR, Vanase-Frawley MA, Kablaoui NM, Systematic N-methylation of oxytocin: Impact on pharmacology and intramolecular hydrogen bonding network, Bioorg. Med. Chem 24 (16) (2016) 3513–3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Muttenthaler M, Andersson A, de Araujo AD, Dekan Z, Lewis RJ, Alewood PF, Modulating oxytocin activity and plasma stability by disulfide bond engineering, J. Med. Chem 53 (24) (2010) 8585–8596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Koehbach J, Gruber CW, From ethnopharmacology to drug design, Commun. Integr. Biol 6 (6) (2013) e27583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zingg HH, Laporte SA, The oxytocin receptor, Trends Endocrinol. Metab 14 (5) (2003) 222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pittman QJ, Spencer SJ, Neurohypophysial peptides: gatekeepers in the amygdala, Trends Endocrinol. Metab 16 (8) (2005) 343–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Song Z, Albers HE, Cross-talk among oxytocin and arginine-vasopressin receptors: relevance for basic and clinical studies of the brain and periphery, Front. Neuroendocrinol (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gimpl G, Fahrenholz F, The oxytocin receptor system: structure, function, and regulation, Physiol. Rev 81 (2) (2001) 629–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Manning M, Misicka A, Olma A, Bankowski K, Stoev S, Chini B, Durroux T, Mouillac B, Corbani M, Guillon G, Oxytocin and vasopressin agonists and antagonists as research tools and potential therapeutics, J. Neuroendocrinol 24 (4) (2012) 609–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Raggenbass M, Overview of cellular electrophysiological actions of vasopressin, Eur. J. Pharmacol 583 (2–3) (2008) 243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Reversi A, Rimoldi V, Marrocco T, Cassoni P, Bussolati G, Parenti M, Chini B, The oxytocin receptor antagonist atosiban inhibits cell growth via a “biased agonist” mechanism, J. Biol. Chem 280 (16) (2005) 16311–16318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Reversi A, Cassoni P, Chini B, Oxytocin receptor signaling in myoepithelial and cancer cells, J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 10 (3) (2005) 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Busnelli M, Sauliere A, Manning M, Bouvier M, Gales C, Chini B, Functional selective oxytocin-derived agonists discriminate between individual G protein family subtypes, J. Biol. Chem 287 (6) (2012) 3617–3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gravati M, Busnelli M, Bulgheroni E, Reversi A, Spaiardi P, Parenti M, Toselli M, Chini B, Dual modulation of inward rectifier potassium currents in olfactory neuronal cells by promiscuous G protein coupling of the oxytocin receptor, J. Neurochem 114 (5) (2010) 1424–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kolaj M, Renaud LP, Vasopressin acting at Vl-type receptors produces membrane depolarization in neonatal rat spinal lateral column neurons, Prog. Brain Res 119 (1998) 275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Taylor JH, Schulte NA, French JA, Toews ML, Binding characteristics of two oxytocin variants and vasopressin at oxytocin receptors from four primate species with different social behavior patterns, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yin K, Baillie GJ, Vetter I, Neuronal cell lines as model dorsal root ganglion neurons: a transcriptomic comparison, Mol. Pain 12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cassoni P, Sapino A, Stella A, Fortunati N, Bussolati G, Presence and significance of oxytocin receptors in human neuroblastomas and glial tumors, Int. J. Cancer 77 (5) (1998) 695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pierce ML, Mehrotra S, Mustoe AC, French JA, Murray TF, A comparison of the ability of leu(8)- and pro(8)-Oxytocin to regulate intracellular Ca(2+) and Ca (2+)-Activated K(+) channels at human and marmoset oxytocin receptors, Mol. Pharmacol 95 (4) (2019) 376–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhou XB, Lutz S, Steffens F, Korth M, Wieland T, Oxytocin receptors differentially signal via Gq and Gi proteins in pregnant and nonpregnant rat uterine myocytes: implications for myometrial contractility, Mol. Endocrinol 21 (3) (2007) 740–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Murthy KS, Makhlouf GM, Opioid mu, delta, and kappa receptor-induced activation of phospholipase C-beta 3 and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase is mediated by Gi2 and G(o) in smooth muscle, Mol. Pharmacol 50 (4) (1996) 870–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ritter SL, Hall RA, Fine-tuning of GPCR activity by receptor-interacting proteins, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 10 (12) (2009) 819–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Vergara C, Latorre R, Marrion NV, Adelman JP, Calcium-activated potassium channels, Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 8 (3) (1998) 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sanchez M, McManus OB, Paxilline inhibition of the alpha-subunit of the high-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel, Neuropharmacology 35 (7) (1996) 963–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Nguyen HM, Singh V, Pressly B, Jenkins DP, Wulff H, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Structural insights into the atomistic mechanisms of action of small molecule inhibitors targeting the KCa3.1 channel pore, Mol. Pharmacol 91 (4) (2017) 392–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Staal RG, Khayrullina T, Zhang H, Davis S, Fallon SM, Cajina M, Nattini ME, Hu A, Zhou H, Poda SB, Zorn S, Chandrasena G, Dale E, Cambpell B, Biilmann Ronn LC, Munro G, Mller T, Inhibition of the potassium channel KCa3.1 by senicapoc reverses tactile allodynia in rats with peripheral nerve injury, Eur. J. Pharmacol 795 (2017) 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Blatz AL, Magleby KL, Single apamin-blocked Ca-activated K+ channels of small conductance in cultured rat skeletal muscle, Nature 323 (6090) (1986) 718–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lamy C, Goodchild SJ, Weatherall KL, Jane DE, Liegeois JF, Seutin V, Marrion NV, Allosteric block of KCa2 channels by apamin, J. Biol. Chem 285 (35) (2010) 27067–27077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lee K, Rowe IC, Ashford ML, NS 1619 activates BKCa channel activity in rat cortical neurones, Eur. J. Pharmacol 280 (2) (1995) 215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Edwards G, Niederste-Hollenberg A, Schneider J, Noack T, Weston AH, Ion channel modulation by NS 1619, the putative BKCa channel opener, in vascular smooth muscle, Br. J. Pharmacol 113 (4) (1994) 1538–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sankaranarayanan A, Raman G, Busch C, Schultz T, Zimin PI, Hoyer J, Kohler R, Wulff H, Naphtho[l,2-d]thiazol-2-ylamine (SKA-31), a new activator of KCa2 and KCa3.1 potassium channels, potentiates the endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor response and lowers blood pressure, Mol. Pharmacol 75 (2) (2009) 281–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Christophersen P, Wulff H, Pharmacological gating modulation of small- and intermediate-conductance Ca(2 + )-activated K( + ) channels (KCa2.x and KCa3.1), Channels Austin (Austin) 9 (6) (2015) 336–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Boratyn GM, Schaffer AA, Agarwala R, Altschul SF, Lipman DJ, Madden TL, Domain enhanced lookup time accelerated BLAST, Biol. Direct 7 (2012) 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Dravid SM, Murray TF, Spontaneous synchronized calcium oscillations in neocortical neurons in the presence of physiological [Mg(2+)]: involvement of AMPA/kainate and metabotropic glutamate receptors, Brain Res. 1006 (1) (2004) 8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Quynh Doan NT, Christensen SB, Thapsigargin, origin, chemistry, structure-activity relationships and prodrug development, Curr. Pharm. Des 21 (38) (2015) 5501–5517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Baxter DF. Kirk M, Garcia AF, Raimondi A, Holmqvist MH, Flint KK, Bojanic D, Distefano PS, Curtis R, Xie Y, A novel membrane potential-sensitive fluorescent dye improves cell-based assays for ion channels, J. Biomol. Screen 7 (1) (2002) 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Whiteaker KL, Gopalakrishnan SM, Groebe D, Shieh CC, Warrior U, Burns DJ, Coghlan MJ, Scott VE, Gopalakrishnan M, Validation of FLIPR membrane potential dye for high throughput screening of potassium channel modulators, J. Biomol. Screen 6 (5) (2001) 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Luttrell LM, Maudsley S, Bohn LM, Fulfilling the promise of “Biased” g protein-coupled receptor agonism, Mol. Pharmacol 88 (3) (2015) 579–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Murray TF, Siebenaller JF, Differential susceptibility of guanine nucleotidebinding proteins to pertussis toxin-catalyzed ADP-ribosylation in brain membranes of two congeneric marine fishes, Biol. Bull 185 (3) (1993) 346–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zhou Y, Lingle CJ, Paxilline inhibits BK channels by an almost exclusively closed-channel block mechanism, J. Gen. Physiol 144 (5) (2014) 415–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Mustoe A, Taylor JH, French JA, Oxytocin structure and function in new world monkeys: from pharmacology to behavior, Integr. Zool (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ren D, Chin KR, French JA, Molecular variation in AVP and AVPRla in New World monkeys (Primates, platyrrhini): evolution and implications for social monogamy, PLoS One 9 (10) (2014) el 11638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Cavanaugh J, Mustoe AC, Taylor JH, French JA, Oxytocin facilitates fidelity in well-established marmoset pairs by reducing sociosexual behavior toward opposite-sex strangers, Psychoneuroendocrinology 49 (2014) 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mustoe AC, Cavanaugh J, Harnisch AM, Thompson BE, French JA, Do marmosets care to share? Oxytocin treatment reduces prosocial behavior toward strangers, Horm. Behav 71 (2015) 83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Luttrell LM, Maudsley S, Gesty-Palmer D, Translating in vitro ligand bias into in vivo efficacy, Cell. Signal 41 (2018) 46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].LePage KT, Dickey RW, Gerwick WH, Jester EL, Murray TF, On the use of neuro-2a neuroblastoma cells versus intact neurons in primary culture for neurotoxicity studies, Crit. Rev. Neurobiol 17 (1) (2005) 27–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Rifkin RA, Moss SJ, Slesinger PA, G protein-gated potassium channels: a link to drug addiction, Trends Pharmacol. Sci 38 (4) (2017) 378–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Murray TFS, Siebenaller JF, Differential Susceptibility of Guanine Nucleotidebinding Proteins to Pertussis Toxin-catalyzed ADP-ribosylation in Brain Membranes of Two Congeneric Marine Fishes, Bio. Bull 185 (1993) 346–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kang J, Huguenard JR, Prince DA, Development of BK channels in neocortical pyramidal neurons, J. Neurophysiol 76 (1) (1996) 188–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Che T, Sun H. Li J, Yu X, Zhu D, Xue B, Liu K, Zhang M, Kunze W, Liu C, Oxytocin hyperpolarizes cultured duodenum myenteric intrinsic primary afferent neurons by opening BK(Ca) channels through IP(3) pathway, J. Neurochem 121 (4) (2012) 516–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Turner RW, Kruskic M, Teves M, Scheidl-Yee T, Hameed S, Zamponi GW, Neuronal expression of the intermediate conductance calcium-activated potassium channel KCa3.1 in the mammalian central nervous system, Pflugers Arch. 467 (2) (2015) 311–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Crespi BJ, Oxytocin, testosterone, and human social cognition, Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc 91 (2) (2016) 390–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Missig G, Ayers LW, Schulkin J, Rosen JB, Oxytocin reduces background anxiety in a fear-potentiated startle paradigm, Neuropsychopharmacology 35 (13) (2010) 2607–2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Baumgartner T, Heinrichs M, Vonlanthen A, Fischbacher U, Fehr E, Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans, Neuron 58 (4) (2008) 639–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Cavanaugh J, Carp SB, Rock CM, French JA, Oxytocin modulates behavioral and physiological responses to a stressor in marmoset monkeys, Psychoneuroendocrinology 66 (2016) 22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Anagnostou E, Soorya L, Chaplin W, Bartz J, Halpern D, Wasserman S, Wang AT, Pepa L, Tanel N, Kushki A, Hollander E, Intranasal oxytocin versus placebo in the treatment of adults with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial, Mol. Autism 3 (1) (2012) 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Ji H, Su W, Zhou R, Feng J, Lin Y, Zhang Y, Wang X, Chen X, Li J, Intranasal oxytocin administration improves depression-like behaviors in adult rats that experienced neonatal maternal deprivation, Behav. Pharmacol 27 (8) (2016) 689–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Brambilla M, Cotelli M, Manenti R, Dagani J, Sisti D, Rocchi M, Balestrieri M, Pini S, Raimondi S, Saviotti FM, Scocco P, de Girolamo G , Oxytocin to modulate emotional processing in schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, cross-over clinical trial, Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 26 (10) (2016) 1619–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Pedersen CA, Gibson CM, Rau SW, Salimi K, Smedley KL, Casey RL, Leserman J, Jarskog LF, Penn DL, Intranasal oxytocin reduces psychotic symptoms and improves Theory of Mind and social perception in schizophrenia, Schizophr. Res 132 (1) (2011) 50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Frijling JL, Preventing PTSD with oxytocin: effects of oxytocin administration on fear neurocircuitry and PTSD symptom development in recently trauma-exposed individuals, Eur. J. Psychotraumatol 8 (1) (2017) 1302652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Viteri OA, Sibai BM, Challenges and limitations of clinical trials on labor induction: a review of the literature, AJP Rep. 8 (4) (2018) e365–e378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Theunissen FJ, Chinery L, Pujar YV, Current research on carbetocin and implications for prevention of postpartum haemorrhage, Reprod. Health 15 (Suppl 1) (2018) 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.