One hundred percent of primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cases are associated with Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). PEL cell lines, such as BCBL-1, are the workhorse for understanding this human oncovirus and the host pathways that KSHV dysregulates. Understanding their function is important for developing new therapies as well as identifying high-risk patient groups. The myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88)/interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK) pathway, which has progrowth functions in other B cell lymphomas, has not been fully explored in PEL. By performing CRISPR/Cas9 knockout (KO) studies targeting the IRAK pathway in PEL, we were able to determine that established PEL cell lines can circumvent the loss of IRAK1, IRAK4, and MYD88; however, the deletion clones are deficient in interleukin-10 (IL-10) production. Since IL-10 suppresses T cell function, this suggests that the IRAK pathway may serve a function in vivo and during early-stage development of PEL.

KEYWORDS: CRISPR, herpesvirus, IRAK, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, lymphoma, MYD88, PEL, Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia

ABSTRACT

Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is necessary but not sufficient for primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) development. Alterations in cellular signaling pathways are also a characteristic of PEL. Other B cell lymphomas have acquired an oncogenic mutation in the myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88) gene. The MYD88 L265P mutant results in the activation of interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK). To probe IRAK/MYD88 signaling in PEL, we employed CRISPR/Cas9 technology to generate stable deletion clones in BCBL-1Cas9 and BC-1Cas9 cells. To look for off-target effects, we determined the complete exome of the BCBL-1Cas9 and BC-1Cas9 cells. Deletion of either MYD88, IRAK4, or IRAK1 abolished interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) signaling; however, we were able to grow stable subclones from each population. Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of IRAK4 knockout cell lines (IRAK4 KOs) showed that the IRAK pathway induced cellular signals constitutively, independent of IL-1β stimulation, which was abrogated by deletion of IRAK4. Transient complementation with IRAK1 increased NF-κB activity in MYD88 KO, IRAK1 KO, and IRAK4 KO cells even in the absence of IL-1β. IL-10, a hallmark of PEL, was dependent on the IRAK pathway, as IRAK4 KOs showed reduced IL-10 levels. We surmise that, unlike B cell receptor (BCR) signaling, MYD88/IRAK signaling is constitutively active in PEL, but that under cell culture conditions, PEL rapidly became independent of this pathway.

IMPORTANCE One hundred percent of primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cases are associated with Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). PEL cell lines, such as BCBL-1, are the workhorse for understanding this human oncovirus and the host pathways that KSHV dysregulates. Understanding their function is important for developing new therapies as well as identifying high-risk patient groups. The myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88)/interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK) pathway, which has progrowth functions in other B cell lymphomas, has not been fully explored in PEL. By performing CRISPR/Cas9 knockout (KO) studies targeting the IRAK pathway in PEL, we were able to determine that established PEL cell lines can circumvent the loss of IRAK1, IRAK4, and MYD88; however, the deletion clones are deficient in interleukin-10 (IL-10) production. Since IL-10 suppresses T cell function, this suggests that the IRAK pathway may serve a function in vivo and during early-stage development of PEL.

INTRODUCTION

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is an incurable B cell lymphoma. The medium survival time is estimated at 6 months following diagnosis. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is the etiological agent of PEL. Unlike the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), KSHV infection of primary human cells in culture does not cause transformation. This suggests that host cell mutations are required to explain the PEL phenotype, in addition to virus infection (1). As with all other cancers, these host mutations can be inborn, existing prior to KSHV infection, or they can develop under selection during tumor evolution. Tumor suppressor genes, such as p53 and Rb, exemplify the former, and the latter are demonstrated by BCL6 and c-Myc, which become activated during germinal center passage of B cells and contribute to Burkitt lymphoma (2).

PEL is observed primarily in end-stage AIDS patients, although isolated cases of PEL have also been reported in HIV-negative patients (reviewed in reference 3). Most PEL cases arise in male patients. PEL manifests as effusions in body cavities such as the peritoneum. Several PEL effusions gave rise to culture-adopted cell lines, such as BC-1 (4) and BCBL-1 (5). During initial outgrowth, these cell lines depended heavily on autologous human serum but later adapted to growth in solely fetal bovine serum. PEL persists in a highly inflammatory environment, often with concurrent microbial infections. Markers of inflammation, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), precede lymphoma development in AIDS patients, and IL-1β is one of the cytokines that is elevated in Kaposi sarcoma (KS) lesions as well as in KSHV-associated multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD) (6–10). It remains unknown how this inflammatory microenvironment shapes PEL tumor initiation and growth. This represents a gap in our knowledge of KSHV biology. Understanding the impact of predisposing genome variants in inflammatory signaling pathways may uncover novel targets of intervention and/or prevention for PEL.

Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) functions in the myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88)/IRAK pathway, an immune signaling pathway that relays signals from Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and interleukin receptors (ILRs) (11–13). When one of these receptors recognizes a ligand, the receptors dimerize, resulting in the recruitment of the adapter protein MYD88. MYD88 then recruits interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4), which undergoes autophosphorylation and activation. IRAK4 recruits IRAK1 to form a large complex composed of multimerized MYD88, IRAK4, and IRAK1 proteins, termed the “myddosome” (14). There are two additional interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases: IRAK2 and IRAKM. IRAK2 has recently been shown to have limited kinase activity, and IRAKM is an inhibitory protein, which is not expressed in PEL (15–17). IRAK4 phosphorylates IRAK1, which induces IRAK1 autophosphorylation at T209 and release from the myddosome (13, 18). Phosphorylated IRAK1 activates TRAF6/TAK1, translocating p65/RELA into the nucleus and activating multiple NF-κB-responsive genes. IRAK1 is then either degraded or marked for nuclear transport through K48 or K63 ubiquitination, respectively (13, 19, 20). IRAK1 is necessary and sufficient for IL-1β signaling in most cells, including B cells (11, 21). There are, however, cell lineages that deviate from this rule, where IRAK2 can substitute for IRAK1 (22) or where the presence of the IRAK1 protein is required but not its kinase activity (13). Additionally, MYD88 can signal through other downstream adaptors in addition to IRAK1/4, depending on the nature of the trigger (18, 23, 24).

Pertinent to B cell lymphoma, MYD88 is found to harbor a mutation, L265P, which results in constitutive activation of the IRAK pathway in a fraction—44% to 75% subtype specific—of diffuse large B cell lymphoma cases, and over 85% of Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (WM) cases (25–30). WM is of postgerminal center lineage, like PEL, and has features of both plasma cells and lymphoid cells. Treating WM cells with an IRAK4 inhibitor or a MYD88 inhibitor was effective at reducing cellular proliferation, demonstrating that the IRAK pathway could potentially serve as a drug target for WM (31–34). In this study, we set out to understand the IRAK pathway in PEL and to test the hypothesis that this pathway could, as in WM, be exploited as a therapeutic target.

RESULTS

MYD88 is functional, but dispensable for PEL growth.

PEL has a unique B cell signaling pathway network consistent with its presumed cell of origin (35–37). Unlike other B cell lymphomas, PEL does not express an active B cell receptor, CD79 or CD20 (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, PEL does not express Burton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK). Rather, PEL expresses high levels of MYD88, TLR1, -3, -4, and -6 to -10, CCR5, and IL-10. TLR7/8 signaling is functional in PEL and results in KSHV reactivation (38). The MYD88 coding regions for the BCBL-1, BC-1, BC3, BCP1, JSC1, and VG1 PEL lines as well as seven primary PEL patient samples were sequenced to test whether PEL contains activating mutations in MYD88 (Fig. 1B). The MYD88 gene sequence was wild type (WT) in each instance, and no L265P activating mutation was observed (Fig. 1C and D).

FIG 1.

PEL cells do not contain the L265P mutation in MYD88. (A) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) analysis of mRNA levels in PEL and lymphoma for BTK, BCR, TLRs, and MYD88 (from PRJNA91407). Shown on the vertical axis is the relative expression on a log10 scale. Shown on the horizontal axis is classification as PEL or not. “Yes” means the cells are PEL and “No” represents non-PEL samples. Colors indicate the presence of EBV in the sample. (B) Genomic DNA from several KSHV-positive PEL cell lines, KSHV-negative B cell lymphoma cell lines, and HIV-positive patient samples (PEL and non-PEL) was PCR-amplified. The ∼400-bp amplicon flanking MYD88 exon 5 PCR product was run on an agarose gel. (C) The PCR products were subjected to Sanger sequencing to screen for the Leu265Phe (L265P) mutation in exon 5 of MYD88. Trace file of MYD88 exon 5 in BC-1 cell line. Exon 5 is highlighted in green, and the codon for L265 is in pink. (D) Table summarizing which MYD88 exons were examined from each cell line or patient sample. WT, wild type; #, number of clones sequenced; non-PEL, normal tissue; nd, not determined.

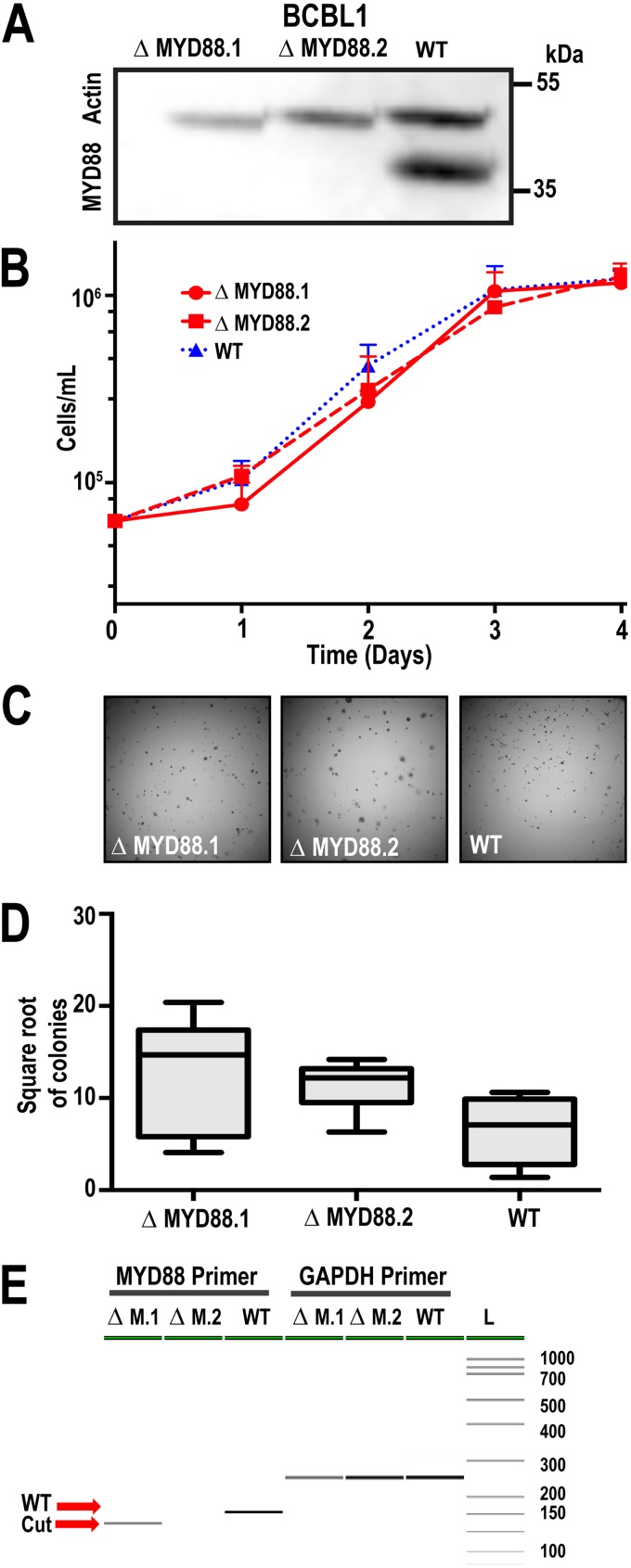

To test the hypothesis that MYD88 is essential for PEL survival, we utilized a two-part CRISPR system. First, we generated stable Cas9-expressing cells, BCBL-1-Cas9. Following selection for stable constitutively expressing Cas9-positive cells, we infected these cells with lentiviral vectors encoding MYD88-targeting guide RNAs (gRNAs). We generated two MYD88-deficient cell lines (ΔMYD88.1 and ΔMYD88.2) following two rounds of single-cell cloning. Western blot analysis showed that MYD88 protein was no longer expressed (Fig. 2A). The growth rates of the ΔMYD88 cells were the same as for empty vector-infected subclones that had undergone the same procedure or for wild-type BCBL-1Cas9 cells (Fig. 2B). There was no difference in the ability of the ΔMYD88 cells to form colonies in soft agar, a rigorous measure of single-cell viability (Fig. 2C and D). Flanking PCR was used to verify genomic DNA editing. The PCR product was run on a LabChip GX Touch HT (Perkin Elmer) instrument and showed that the MYD88 gene was edited in the ΔMYD88.1 and ΔMYD88.2 cells compared to that in nonedited WT cells (Fig. 2E). In summary, MYD88 was not mutated and is dispensable for growth of BCBL-1Cas9 cells in culture.

FIG 2.

MYD88 is not required for PEL survival. (A) MYD88 Western blot of BCBL-1Cas9 cell line (WT) and two independent sublines, ΔMYD88.1 and ΔMYD88.2, deleted for MYD88; loading control is β-actin. (B) Growth curves for parent and ΔMYD88 clones obtained via trypan blue cell counting. Two ΔMYD88 clones and an empty vector control were used in this experiment. (C) Representative images from colony formation assays of ΔMYD88 and WT BCBL-1Cas9 cells imaged at ×10 magnification. Cells were plated in 1% methylcellulose medium and grown for 3 weeks. (D) Quantification of colony formation. Colony counts were obtained using ImageJ and the square root of the number of colonies was plotted; n = 15. (E) PCR analysis using primers that flanking the CRISPR target site. Visualization using PerkinElmer LabChip GX-Touch.

IRAK signaling is functional in PEL but can be readily dispensed with upon selection.

We had previously shown that 95% of PEL cases have a nonsynonymous single nucleotide variant (SNV) (rs1059702) in the coding region of IRAK1 (15). Since the same SNV was present in primary PEL biopsy specimens, it is unlikely that this represents an adaptation to growth in culture. IRAK1 has multiple isoforms (13, 39). We determined that the three canonical splice variants of IRAK1 were transcribed in PEL. Additionally, we observed a previously unreported fourth IRAK1 isoform. A protein in size consistent with that of the full-length isoform was observed by Western blot analysis, but no smaller species (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

IRAK1 is not required for PEL survival. (A) IRAK1 Western blot of BCBL-1Cas9 cell lines showing complete knockout; loading control is β-actin. (B) Growth curves for BCBL-1Cas9 ΔIRAK1 clones obtained via trypan blue cell counting. Two ΔIRAK1 clones and an empty vector control were used in this experiment. (C) Representative images from colony formation assays of ΔIRAK1 BCBL-1Cas9 cells imaged at ×10 magnification. Cells were plated at a low cell density in 1% methylcellulose medium and grown for 3 weeks. (D) Quantification of colony formation in BCBL-1Cas9 ΔIRAK1 stable cell lines. Colony counts were obtained using ImageJ, and the square root of the number of colonies was plotted; n = 15. (E) Flanking cut-site PCR analysis using PerkinElmer LabChip GX-Touch. Primers were designed flanking the cut site. Image analysis revealed changes in band size of the KO versus that of WT cells.

To test the hypothesis that IRAK1 was essential for PEL survival, we again used CRISPR to generate IRAK1 knockout BCBL-1-Cas9 cell lines, ΔIRAK1.1 and ΔIRAK1.2 (Fig. 3). Western blotting verified the absence of IRAK1 protein (Fig. 3A). Proliferation rates for knockouts were not significantly different from that of the WT (Fig. 3B) nor was colony formation in semisolid medium (Fig. 3C and D). PCR with flanking primers confirmed that IRAK1 had been deleted and that the primer binding sites were removed (Fig. 3E). This was confirmed by whole-exome sequencing. The complete exome sequences of the parent and deletion cell lines were determined by next-generation sequencing (NGS) to explore possible off-target effects of CRISPR/Cas-9 mutagenesis. As expected, both private and common SNVs were observed, but none in regions of known clinical or biological significance (SRA PRJNA596731). The pattern repeated itself with IRAK4, the activating kinase for IRAK1. We were able to obtain stable deletion clones of BCBL-1Cas9 cells, ΔIRAK4.1 and ΔIRAK4.2, that had no discernible growth disadvantage. Western blots showed an effective knockout (Fig. 4A), and cellular growth was observed to be the same as for the WT (Fig. 4B). There was no difference for growth in semisolid medium for ΔIRAK4 cells compared to that for WT cells (Fig. 4C and D). Deletion of IRAK1 was verified by PCR (Fig. 4E). In conclusion, PEL can survive in culture in the absence of IRAK or MYD88 signaling. These experiments were repeated in a second PEL cell line, BC-1, to confirm that the results we obtained in BCBL-1 were not cell line specific (Fig. 5). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutation abrogated MYD88, IRAK1, and IRAK4 protein expression (Fig. 5A to C). Of note, in the case of the BC-1 IRAK4 deletion (Fig. 5C), we observed a shift toward higher protein mobility, implying that the mutagenesis generated a fusion protein rather than a clean deletion. None of the three gene deletions impacted the growth of BC-1 cells in culture or the ability of BC-1 cells to form colonies in a semisolid medium (Fig. 5G to I).

FIG 4.

IRAK4 is not required for PEL survival. (A) IRAK4 Western blot of BCBL-1Cas9 cell lines showing complete knockout; loading control is β-actin. (B) Growth curves for BCBL-1Cas9 ΔIRAK4 clones obtained via trypan blue cell counting. Two ΔIRAK4 clones and an empty vector control were used in this experiment. (C) Representative images from colony formation assays of ΔIRAK4 BCBL-1Cas9 cells imaged at ×10 magnification. Cells were plated at a low cell density in 1% methylcellulose medium and grown for 3 weeks. (D) Quantification of colony formation in BCBL-1Cas9 ΔIRAK4 stable cell lines. Colony counts were obtained using ImageJ, and the square root of the number of colonies was plotted; n = 15. (E) Flanking cut-site PCR analysis using PerkinElmer LabChip GX-Touch. Primers were designed flanking the cut site. Image analysis revealed changes in band size of the knockout versus that of WT cells.

FIG 5.

MYD88, IRAK1, and IRAK4 are dispensable in BC-1 cells. (A) MYD88 Western blot of BC-1Cas9 cell lines showing complete knockout; loading control is β-actin. (B) IRAK1 Western blot. (C) IRAK4 western blot. (D) Growth curves for BC-1Cas9 ΔMYD88 clones obtained via trypan blue cell counting. Two ΔMYD88 clones and an empty-vector WT control were used in this experiment. (E) Growth curves for BC-1Cas9 ΔIRAK1 clones. (F) Growth curves for BC-1Cas9 ΔIRAK4 clones. (G) Quantification of colony formation in BCBL-1Cas9 ΔMYD88 stable cell lines. Colony counts were obtained using ImageJ, and the square root of the number of colonies was plotted; n = 15. (H) Quantification of colony formation in BCBL-1Cas9 ΔIRAK1 stable cell lines. (I) Quantification of colony formation in BCBL-1Cas9 ΔIRAK4 stable cell lines.

To test the hypothesis that BCBL-1Cas9 cells were capable of MYD88/IRAK signaling, control and deletion clones were exposed to IL-1β. The phosphorylation status of NF-κB (p65) was probed using phospho (p)-NF-κB-specific antibodies. No NF-κB phosphorylation was observed in any of the deletion clones, whereas WT BCBL-1Cas9 had a strong p-NF-κB signal in response to IL-1β stimulation within 10 min of exposure to 1 ng/ml IL-1β (Fig. 6A, 7A, and 8A). Additionally, MYD88/IRAK activation was evaluated by NF-κB reporter assay. Wild-type BCBL-1Cas9 responded robustly to IL-1β (Fig. 6B and C, 7B and C, and 8B and C). By contrast, IRAK1-, IRAK-4, and MYD88-deleted clones did not respond. Levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-induced activation were similar across all cell lines, demonstrating that the luciferase plasmids were present and functional in these experiments, as TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB is independent of the MYD88/IRAK pathway (Fig. 6 to 8) (40). The IL-1β experiments demonstrated that each of the three components of the IL-1β pathway, MYD88, IRAK1, and IRAK4, are functional in PEL and are independently required to transmit IL-1β-initiated signals.

FIG 6.

NF-κB activation by IL-1β is not functional in ΔMYD88 clones. (A) A Western blot for phospho-NF-κB and the IRAK pathway proteins IRAK1, IRAK4 and MYD88 in WT and ΔMYD88 BCBL-1Cas9 cells 15 min post IL-1β stimulation (1 ng/μl IL-1β). (B) Quantification of luciferase production using an NF-κB reporter assays system. Two ΔMYD88 clones and WT BCBL-1Cas9 cells were stimulated with 1 ng/μl IL-1β, or mock PBS for 24 h h following transfection, and luciferase values measured 6 h h post stimulation. Results are fold change over mock. (C) Two ΔMYD88 clones and WT BCBL-1Cas9 cells were stimulated with TNF-α (1 ng/ml), and the response was compared to mock using the same procedure as in panel B.

FIG 7.

NF-κB activation by IL-1β is not functional in ΔIRAK1 cells. (A) Western blot for p-NF-κB and the IRAK pathway proteins in WT and ΔIRAK1 BCBL-1Cas9 cells 15 min post-IL-1β stimulation (1 ng/μl IL-1β). (B) Quantification of luciferase production using an NF-κB reporter assay system. Two ΔIRAK1 clones and WT BCBL-1Cas9 cells were stimulated with 1 ng/μl IL-1β or mock PBS. Cells were stimulated 24 h following transfection, and luciferase values were measured 6 h poststimulation. Results are fold change over mock. (C) Two ΔIRAK1 clones and WT BCBL-1Cas9 cells were stimulated with TNF-α, and the response was compared to that with mock using the same procedure as for panel B.

FIG 8.

NF-κB activation by IL-1β is not functional in ΔIRAK4 cells. (A) Western blot for p-NF-κB and the IRAK pathway proteins in WT and ΔIRAK4 BCBL-1Cas9 cells 15 min post-IL-1β stimulation (1 ng/μl IL-1β). (B) Quantification of luciferase production using an NF-κB reporter assay system. Two ΔIRAK4 clones and WT BCBL-1Cas9 cells were stimulated with 1 ng/μl IL-1β or mock PBS. Results are fold change over mock. Cells were stimulated 24 h following transfection, and luciferase values were measured 6 h poststimulation. (C) Two ΔIRAK4 clones and WT BCBL-1Cas9 cells were stimulated with TNF-α, and the response was compared to that with mock using the same procedure as for panel B.

To verify that only the intended gene in the pathway was deleted and that downstream responses remained fully functional in the deletion clones, we performed complementation experiments in all knockout cell lines with four different IRAK1 expression plasmids (Fig. 9). Each plasmid expressed full-length IRAK1. pDD1951 encodes the PEL genotype, pDD2149 encodes the D340N site mutation that was previously shown to abolish kinase activity (41), pDD2148 is the non-PEL genotype, and pDD2147 encodes the D340N mutation in the non-PEL background. Empty vector plasmid pDD1957 was used as the control. The kinase-dead IRAK1 isoforms were expressed at higher protein levels, presumably since autophosphorylation primes IRAK1 for ubiquitin-mediated degradation (Fig. 9A) (42). Upon nucleofection of any of the four IRAK isoforms into IRAK1 knockout (KO) cells, NF-κB signaling was restored and active independent of IL-1β (Fig. 9B). Figure 9B and C depict the results of NF-κB reporter assays. Shown are log10-transformed values of relative luciferase activity. The data were standardized by plate, by subtracting the background level and dividing by the maximal response to IL-1β stimulation, i.e., the positive control per plate. This was necessary, as the data represent multiple biological replicates, each at least 1 week apart, and as the magnitude of the response varies somewhat depending on culture conditions, such as cell density and overall time in culture. A post hoc comparison shows a statistically significant (adjusted P ≤ 0.0001) difference between wild-type BCBL-1 and IRAK1 KO cells. WT BCBL-1 cells responded to IL-1β stimulation, whereas IRAK1 KO cells did not. Introduction of any one of the IRAK1 expression plasmids was able to complement the IRAK1 deficiency, whereas the vector plasmid did not (adjusted P ≤ 0.0001 for each pairwise comparison) (Fig. 9B). The same phenotype was detected in IRAK4 and MYD88 KO cells (Fig. 9C). These experiments demonstrate that the downstream targets of IRAK1 were intact in IRAK1, IRAK4, and MYD88 KO cells. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that IRAK1 is downstream of MYD88 and IRAK4 in the signaling pathway, as expected, and that IRAK1 functions in one of the pathways that induce NF-κB in PEL. These results substantiate earlier observations that IRAK1 can induce NF-κB independently of its kinase activity under circumstances of ectopic expression (12, 41, 43–45).

FIG 9.

Complementation of IRAK1 restores signaling function in KO cells. (A) Western blot in WT BCBL-1Cas9 cells showing expression of Myc-tagged IRAK1 in BCBL-1Cas9 cells. (B) IRAK expression plasmids were conucleofected with an NF-κB reporter-driven luciferase plasmid into WT or ΔIRAK1 BCBL-1Cas9 cells. Cells were stimulated with IL-1β or PBS (mock), and luciferase values were measured 6 h poststimulation. Shown are relative activities adjusted across multiple biological replicates and scales as fraction of maximal response on a log10 scale. (C) IRAK expression plasmids were conucleofected with an NF-κB reporter-driven luciferase plasmid into WT, ΔIRAK1, ΔIRAK4, or ΔMYD88 BCBL-1Cas9 cells. Cells were stimulated with IL-1β, TNF-α, or PBS (mock), and luciferase values were measured 6 h poststimulation. Shown are relative activities adjusted across multiple biological replicates and scales as fraction of maximal response on a log10 scale.

Small-molecule tool compounds that target MYD88 and IRAK1/4 exhibit substantial off-target effects.

MYD88, IRAK1, and IRAK4 have been the subject of intensive drug discovery efforts (17, 46–48). Several tool compounds have been developed, and Amgen Inc. has advanced an IRAK1/4 inhibitor into phase I clinical trials for non-cancer indications (49). To explore the phenotypes of inhibiting the MYD88/IRAK4 pathway pharmacologically, we tested the effectiveness of six IRAK, one MYD88, and three BTK inhibitors in PEL (Fig. 10). In vitro kinase assays for 480 human kinases (KINOMEscans) were evaluated on the six presumed IRAK inhibitors to validate target specificity. Most of these compounds showed extensive off-target activity. Three of the IRAK inhibitors were selected for detailed characterization in PEL (Fig. 10C). (i) The Amgen compound “IRAK inhibitor-1-4” had the greatest in vitro specificity. KINOMEscan identified that only four proteins were inhibited by greater than 80% at 250 nM concentration of inhibitor: IRAK1, CLK4, CLK1, and IRAK4. IRAK inhibitor-1-4 was the least effective at killing BCBL-1 cells. Despite having a high 50% effective concentration (EC50) value, IRAK inhibitor-1-4 reduced IL-1β signaling at concentrations that were far below the concentration that was cytotoxic (Fig. 9A). By contrast, the other compounds inhibited IL-1β signaling at roughly the same concentrations at which they showed generalized cytotoxicity (Fig. 10A and B). (ii) Compound “IRAK inhibitor-1” was less specific in vitro. In addition to IRAK4, 19 other kinases were inhibited by greater than 80% at 250 nM (Fig. 10C): FLT3, JAK3, MKNK2, GAK, MEK5, BIKE, RIOK3, PHKG2, RIOK, AAK1, PIP5K2B, PDGFRB, RSK4, PHKG1, KIT, ROCK1, PFCDPK1, RSK1, and SIK2. (iii) Compound “IRAK inhibitor-4,” had no strong hits on the KINOMEscan (Fig. 10C). IRAK1 and IRAK4 were inhibited to ∼20% at 250 nM. Both compounds reduced IL-1β-induced luciferase activity; however, it was not possible to separate the specific IRAK4 inhibition from effects on other targets or cell death caused by the inhibitors, as the EC50 for IL-1β signaling inhibition was equal or above the EC50 for nonspecific growth inhibition (Fig. 10A and B).

FIG 10.

Comparison of in vitro and in culture IRAK inhibitor activity. (A) EC50 curves (growth) for three commercially available IRAK inhibitors. Fraction of response is shown on the vertical axis and concentration (in μM) on the horizontal axis. Inh1 (CAS no. 1042224-63-4), Inh4 (CAS no. 1012104-68-5), and Inh1-4 (CAS no. 509093-47-4). The EC50 value on each plot is the average from four experiments. (B) Quantification of luciferase production in cells transfected with an NF-κB-driven luciferase plasmid, incubated with inhibitor, a nd stimulated with 1 ng/μl IL-1β. Luciferase values were measured 6 h poststimulation. All values are fold change over that with mock PBS stimulation on the vertical axis and inhibitor concentration (in μM) on the horizontal axis. (C) A DiscoverX KINOMEscan analysis for each IRAK inhibitor at 250 nM. Purple or blue dots and represent IRAK4 or IRAK1 kinase, respectively. Size of the circle is proportional to percent activity inhibited by the inhibitors.

Next, these compounds were evaluated in the IRAK and MYD88 KO cells. The MYD88 dimerization inhibitor, ST2825 (24, 31), was included as an additional control. ST2825 killed cells but displayed no change in EC50 values in the WT (8.42 ± 3.44 μM, n = 4) compared to that in the ΔMYD88 (5.16 ± 2.79 μM, n = 4), ΔIRAK1 (8.0 ± 7.6 μM, n = 4), or ΔIRAK4 (14.07 ± 16.6 μM, n = 4) cell lines (Table 1). Likewise, none of the IRAK inhibitors showed any significant change in EC50, comparing WT to ΔIRAK4 BCBL-1Cas9 cells as seen in Table 2. The EC50s for ΔIRAK4 BCBL-1 were 15.08 ± 16.1 μM for IRAK inhibitor-1 (Inh1) (n = 4), 5.1 ± 3.5 μM for Inh4 (n = 4), and 231 ± 236 μM for Inh1-4 (n = 4). This suggests that any antiproliferative activity for these compounds in PEL was independent of their inhibition of IRAK4 kinase activity.

TABLE 1.

Results from treating IRAK pathway knockout cells with the MYD88 ST2825 dimerization inhibitor

| Cell line | EC50 value (μM)a

|

SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replicate 1 | Replicate 2 | Replicate 3 | Avg | ||

| BCBL-1 WT | 4.3 | 7.1 | 8.8 | 6.7 | 2.2 |

| ΔIRAK4.1 | 9.3 | 3.3 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 3.1 |

| ΔIRAK4.2 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 18 | 9.3 | 7.3 |

| ΔIRAK1.1 | 29 | 2.3 | 5.1 | 12 | 14 |

| ΔIRAK2.2 | 16 | 2.6 | 5.4 | 8.0 | 7.0 |

| ΔMYD88.1 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 8.3 | 5.1 | 2.8 |

| ΔMYD88.2 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 7.9 | 4.7 | 2.8 |

Three biological replicates, each the average from 4 technical replicates.

TABLE 2.

EC50 values for three IRAK inhibitors conducted in WT and IRAK4 knockout BCBL-1 cell lines

| Cell line | EC50 value (μM)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IRAK inhibitor-1 | IRAK inhibitor-4 | IRAK inhibitor-1-4 | |

| BCBL-1 WT | 14.9 ± 15 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 275 ± 52 |

| ΔIRAK4.1 | 21.9 + 38 | 6.7 + 1.7 | 334 ± 170 |

| ΔIRAK4.2 | 15.0 ± 16 | 5.1 ± 3.5 | 231 ± 236 |

Represented are the averages and standard deviations from 4 biological replicates.

Baseline IRAK signaling is elevated in PEL, which contributes to PEL-specific paracrine phenotypes and limits viral replication.

To determine the consequences of MYD88/IRAK1/IRAK4 ablation genome wide, transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of ΔIRAK4 and WT BCBL-1Cas9 was conducted under several treatment conditions. Each RNA-seq experiment was conducted across multiple independent deletion clones. There was minimal change between biological replicates harvested 3 weeks apart from the same clone (pairwise Spearman correlation across all mRNAs, 0.9722, 0.9675, and 0.9671 for n = 3 biological replicates). The combined results are summarized in a heat map representation (Fig. 11D). First, we observed differences in baseline gene transcription between WT and ΔIRAK4 BCBL-1Cas9 cells. Two independently derived ΔIRAK4 cell lines were examined, and common transcriptional changes were quantitated using false-discovery rate-adjusted P values for individual genes. Changes are visualized in a Volcano plot (Fig. 11A), which verifies the functional inactivation of IRAK4-dependent immune signaling. When treated with IL-1β, WT cells responded with upregulation of canonical IL-1β-responsive transcripts (Fig. 11B); by contrast, ΔIRAK4 cells did not respond (Fig. 11C).

FIG 11.

RNA-seq analysis of IRAK4 CRISPR KO. (A) Volcano plots showing the genes that were differentially expressed in WT versus that in ΔIRAK4 cells. (B) WT with or without IL-1β. (C) ΔIRAK4 with or without IL-1β. The vertical axis shows negative log10 of the unadjusted P value, the horizontal axis shows log2 of the fold change for each RNA in a paired comparison. (D) Heat map of the top 20 most altered transcripts as obtained by unsupervised clustering of mRNA levels of ΔIRAK4 cells compared to that in WT BCBL-1Cas9 cells under the different conditions indicated at the top. Blue indicates that the gene was downregulated, and red is upregulated relative to the overall mean. IL-1β response genes are indicated on the right. (E) An IPA network map for RNA-seq data comparing WT versus ΔIRAK4. Proteins shaded red are upregulated in ΔIRAK4 versus that in WT, green-shaded proteins are downregulated, blue means it is predicted to be downregulated, and orange is predicted to be upregulated. (F) IL-10 ELISAs were run on IRAK pathway knockouts with data points collected at 48 h. (G) IL-10 ELISAs from 72-h time points, reflecting the same time points as the RNA-seq harvests.

The following genes were transcribed in BCBL-1Cas9 but not in ΔIRAK4 cells in the absence of exogenous IL-1β: ARHGAP30, B2M, BCL7A, ENG, EPB41L3, FTL, HSP90AA1, RPS12, SELPLG, SLC16A3, SULT1A1, and YWHAQ (Fig. 11A and D). Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) suggested that this gene pattern of upregulation in cells is linked to aberrant cellular growth and cancer. The transcription of these genes was abrogated by deletion of IRAK4 as seen in two different clones (Fig. 11D). Hence, we conclude (i) that IRAK signaling is constitutively active in PEL and (ii) that these transcripts mediate the constitutive phenotype of IRAK4 in PEL. Both clones also upregulated a number of transcripts that were not transcribed in WT cells (Fig. 11D). These would be expected to compensate for loss of constitutive IRAK signaling; however, we did not observe any transcripts that were common among both KO clones. Rather, each ΔIRAK4 clone compensated for loss of IRAK4 activity with a unique set of transcriptional adaptations. The significance of these adaptive transcriptional changes is unclear.

IL-10 was one of the transcripts differentially regulated between WT and IRAK4 KO cells. IL-10 is expressed at high levels in BCBL-1 cells and many other PEL cell lines (9, 50), and IL-10 is central to the biology of PEL and KSHV infection in vivo, e.g., in KSHV-associated inflammatory cytokine syndrome (KICS) (51). An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) verified the transcriptional phenotype for secreted IL-10 protein across all IRAK KO cell lines (Fig. 11F and G). IL-10 levels were lower in the IRAK1, IRAK4, and MYD88 knockout cell lines compared to that in wild-type BCBL-1Cas9 cells, demonstrating the robustness of the profiling results.

To put the individual changes in gene transcription into context, we conducted gene network analyses using Qiagen IPA software. IRAK4 KO cells exhibited a decrease in TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β networks compared to that in the WT. Knockout of IRAK4 translated into an overall downregulation of the proinflammatory milieu, which is a classic hallmark of PEL (Fig. 11E).

DISCUSSION

All PEL cases require KSHV for survival. Dual-infected PEL cases require both KSHV and EBV, presumably because EBV stabilizes the KSHV episome (52–54). In addition, PEL also acquired multiple genetic changes in the host genome, analogous to EBV-transformed B cell lymphoma (BL) (55, 56). PEL’s rarity has provided a challenge to developing definitive genomic analyses. Within these limitations, however, several SNVs in the protein-coding regions of genes were identified, present across multiple PEL cases and cell lines at a higher frequency than in the general population (15). One of these SNVs occurred on the IRAK1 gene, which is located on the X chromosome and transcribed in PEL. IRAK1, IRAK4, and MYD88 constitute the myddosome, which mediates IL-1β and TLR signaling. MYD88 is mutationally activated in a large proportion of diffuse large B cell lymphomas, such as WM, resulting in constitutive activation of the MYD88/IRAK pathway and driving the proliferation of these cancers (29, 57, 58). This phenomenon prompted us to explore the biological function of MYD88/IRAK signaling in PEL.

MYD88 was not mutated in any of the PEL cases analyzed, and upon CRISPR/Cas9-facilitated deletion of MYD88, the BCBL-1Cas9 PEL cell line rapidly acquired MYD88/IRAK independence (Fig. 1 and 4). The same phenotype of IRAK independence was observed in BC-1 cells (Fig. 5). Furthermore, MYD88-deleted cells were deficient in IL-1β signaling (Fig. 6). The same held true for IRAK1- and IRAK4-deleted BCBL-1Cas9 cells (Fig. 7 and 8). Interestingly, IRAK4-deleted BCBL-1Cas9 cells lost the expression of several genes that were highly transcribed at steady state, i.e., prior to IL-1β stimulation and in the presence of an IRAK1/4 kinase inhibitor. One of these target genes was IL-10. IL-10 secretion was downregulated in every MYD88, IRAK1, or IRAK4 deletion clone (Fig. 11F and G). This suggests that IRAK signaling was constitutively active in PEL, at least the part of the IRAK signaling cascade that is independent of kinase activities, as has been previously observed (13, 43, 44). Another result of these experiments demonstrated that current tool compounds that target IRAK1/4 or MYD88 derived their antiproliferative efficacy in PEL largely from off-target effects (Fig. 10). This does not invalidate the utility of these inhibitors but suggests a different mechanism of action. Since, in PEL, IRAK4 induced both kinase-independent as well as kinase-dependent targets, it remains unclear what the direct benefit of targeting IRAK kinase activity in PEL would be.

Another important piece of information to consider when examining this data is the differences in experimental designs. Small-molecule inhibitor, small interfering RNA (siRNA), and short hairpin RNA (shRNA) screens measure acute phenotypes, often within hours after addition. These agents act effectively on dividing as well as nondividing cells, since they target mRNA or protein and do not depend on homologous recombination. CRISPR/Cas9 requires each cell to traverse multiple replication/division cycles. Our approach of evaluating single-cell clones differed from bulk CRISPR/Cas9 studies that were designed to measure a relative enrichment within the total population. Consistent with our results, Manzano et al. (59) reported a CRISPR/Cas9 screen in which PEL cells survived after deletion of NF-κB, which is a downstream target of IRAK1 as well as a multitude of other signaling pathways. NF-κB is also a target of the KSHV vFLIP protein and, based on pharmacological studies, was believed to be a driver for PEL growth (60–62). Yet, within a few generations, PEL clones that were independent of NF-κB emerged.

Whole-exome sequencing data showed that, like most transformed cell lines, PEL is mutable when exposed to drug selection or CRISPR/Cas9 selection (SRA PRJNA596731) (63). This plasticity is even more evident at the mRNA level, e.g., in response to rapamycin (63). In this study, RNA-seq analysis of the ΔIRAK4 clones demonstrated that the cells adapted other means to support survival, which was the phenotype that the CRISPR/Cas9 experiments selected for (Fig. 11), but they did not adapt a means to transmit the IL-1β signal, since IL-1β responses were not selected for during the CRISPR/Cas9 process (Fig. 4).

It is important to remember that BCBL-1, like all cancer cell lines, has been selected for continuous growth in culture. Therefore, vulnerabilities that exist in patients may not manifest themselves under ideal growth conditions. For example, one would expect direct xenograft models (64) to be more susceptible to agents that modulate autocrine and/or paracrine signaling pathways or that augment the host immune response. IL-1β is present at high levels in KS lesions (65), precedes non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) development in AIDS patients, and likely has its most important role in modulating the PEL microenvironment in vivo (66). One would expect PEL (or KSHV-infected precursors to PEL) to respond to some proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, by releasing IL-10, dampening T cell activity, and counteracting viral clearance. If this is the case, it may explain the prevalence of the IRAK1 SNV seen in PEL patients, as this SNV results in higher levels of NF-κB signaling (67, 68).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Suspension cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco), and adherent cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco). Both media were supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco), and 10% Fetalgro bovine serum (VWR). Stable Cas9-transduced BCBL-1 cells were maintained in 10 μg/ml blasticidin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 and passaged for no more than 3 months at a time. All cell lines were obtained from the ATCC. For short tandem repeat (STR) typing, cell pellets were submitted to Genetica DNA Laboratories, Burlington, NC, using the PowerPlex 16HS assay (Promega) to provide results for 16 genetic test sites. Results were compared to reference data from ATCC. All cells underwent periodical mycoplasma testing (Lonza, LT07-701).

Lentivirus production.

Lentivirus particles were produced in 293T cells using ViraPower (Thermo Fisher, K497500) or purchased from Millipore Sigma Sanger clone library. All plasmids used in the lab are assigned a unique identification number known as a pDD number. CRISPR plasmids were either obtained from Millipore Sigma (pDD2160-61 [IRAK1, HS5000019451-2 and pDD2162-63 [MYD88, HS5000001249-50]) or from Addgene (pDD2125 [cas9, 52962], pDD2126 [EV, 52963], and pDD2127-29 [IRAK4 guides 75664-6]). Packaging mix and transfer plasmid were cotransfected into 293T cells using ViraPower (Thermo Fisher, Inc.), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Virus particles were harvested 48 to 72 h posttransfection, filtered, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until use.

Stable Cas9 cell line generation.

A Cas9 expression plasmid was obtained from Addgene (52962). This Cas9 is under constitutive expression in mammalian systems. 293T cells were transfected with the Cas9 plasmid and ViraPower mix as described in the previous section. Cas9 lentiviruses were harvested, and BCBL-1, BC-1, and BJAB cells were inoculated with the Cas9 lentivirus. Following spinfection, positive Cas9 stable cells were selected using 10 μg/ml blasticidin. Stable blasticidin-resistant cells were probed by Western blotting for Cas9 expression and used in all CRISPR experiments.

Spinfection procedure.

For purchased particles, 50,000 cells were plated in 24-well plates with 100 μl of serum-free medium; 200 μl of particles, multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 (particle titers determined by manufacturer using a p24 assay), were added with 10 μg/ml Polybrene. The plates were centrifuged for 90 min at 1,500 rpm (1,000 × g). Medium was changed 18 h following centrifugation. Selection medium, containing 2.5 μg/ml of puromycin, was added 24 h postcentrifugation. One-half of the cells were plated into three 1-ml colony formation assays for single-cell clone selection (see “Colony formation assay”). Trypan blue (Millipore Sigma, T8154) cell counting was used for all growth proliferation assays and live/dead cell counting.

CRISPR knockout.

For CRISPR KO, we used the same spinfection protocol as mentioned previously and performed a second spinfection with a second guide on the same target cell population. Following the second spinfection, 5,000 cells were plated in a 1% methylcellulose medium with 2 μg/ml puromycin to select for single cell clones. After 3 weeks of growth, clonal colonies were selected and grown in 5 μg/ml puromycin medium. Flanking PCR and gel analysis on a Perkin Elmer LabChip GX Touch HT instrument validated CRISPR cutting. PCR primer sequences for CRISPR validation were as follows: IRAK1-F, 5′-CCTCTGGCCTCACCTGGA; IRAK1-R, 5′-CAGAACGCTGACCTGGAGTG; IRAK1-FB, 5′-TGGTGTGCGGTCTGAAGC; IRAK1-RB, 5′-CTTCGCTTCGAGAGCCTCA; MYD88-F, 5′-GCTGAACTAAGTTGCCACAGGA; MYD88-R, 5′-GAGCTTACCTGGAGAGAGGC; IRAK4-F, 5′-ACTGGAAAAAGTCCCACTTCTGA; IRAK4R, 5′-ACTTTCTTACAGCCTAAGCCAGA; IRAK4-FB, 5′-ACTGGCTGAAAAGAGAAGTATTTGC; and IRAK4-RB, 5′-GGCAACCCAGTTGTTGACAT.

Western blotting.

One million cells were harvested, lysed with 100 μl RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X, 0.1% SDS, 1% Na-deoxycholate, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], H2O) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Millipore Sigma, P8340), 30 mM beta-glycerol phosphate, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and Benzonase nuclease (Millipore Sigma, 712053) and incubated for 30 min on ice, with 15 s of vortexing every 10 min. Depending on the assay, 10 to 15 μl of cell lysate, normalized by cell counts or Bradford assays, was loaded onto 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, separated by electrophoresis, and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore Sigma, GE10600023). Membranes were blocked using 10% milk or OneBlock (Genesee 20-313). Anti-actin rabbit and mouse (4970 and 3700), MYC tag (2272), IRAK1 (4504), MYD88 (4283), NF-κB p65 (8242), and NF-κB Pp65 (3022) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling. Anti-IRAK4 antibody (AF3919) was purchased from R&D systems. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit and mouse secondary antibodies (Vector Labs, PI-1000 and PI-2000) were used to detect Western signals and developed using Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate (Thermo Fisher, 32106) on film (Genesee, 30-810L) or with Clarity ECL (Bio-Rad, 1705061) on a ChemiDoc (Bio-Rad) or iBright (Thermo Fisher) imaging device. For the p-NF-κB (p65) Western blots, samples were harvested 10 min after stimulation with 1 ng/ml of TNF-α or IL-1β.

Colony formation assay.

Cells were plated in 6-well dishes in triplicate using 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), complete RPMI medium, 1% methylcellulose, and 2 μg/ml of puromycin to select for stable knockouts. Light images of wells were obtained 3 weeks after plating, using ×10 magnification. The number of colonies was quantified using ImageJ software.

NF-κB reporter assay.

Three micrograms of Pglo44 NF-κB-driven luciferase reporter plasmid (Promega), pDD3209, was nucleofected into 1 million cells using 100 μl Ingenio electroporation solution (Mirus, MIR50117) and the Lonza 4D nucleofector. Cells were stimulated with 1 ng/ml TNF-α, IL-1β, or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 24 h posttransfection. The luciferase values were measured after 6 h. ONE-Glo (Promega, E6120) firefly reagent was used, and activity was measured using a FLUOstar Optima plate reader (BMG Labtech). We used the same setup as described above to test the effects of inhibitors on luciferase production. Fifteen minutes before stimulation with IL-1β, IRAK inhibitors were added to the plate at 100, 50, and 25 μM. The NF-κB reporter assay was performed at 6 h post-IL-1β stimulation.

IRAK1 complementation.

We obtained three IRAK1 expression plasmids from OriGene, namely, pDD1951 (RC221544, PEL phenotype full-length IRAK1), pDD1952 (RC224107, IRAK1 isoform B), pDD1953 (RC204869, IRAK1 isoform C), and the empty vector control pDD1957 (EV, pCMV6-entry). Blue Heron Biotech synthesized three additional IRAK expression plasmids based on the same pCMV6 vector: pDD2147 (kinase dead non-PEL IRAK1), pDD2148 (IRAK1 non-PEL), and pDD2149 (PEL IRAK1 kinase dead). Each plasmid (3 μg/μl) was nucleofected into 1 million cells using 100 μl Ingenio solution (Mirus) and the Lonza 4D nucleofector. Western blotting was performed 48 h posttransfection. For the complementation experiment to test NF-κB signaling, we cotransfected the expression plasmid pDD3209 with Pglo44 NF-κB plasmid (Promega), stimulated the cells 24 h after nucleofection, and viewed them as described in “NF-κB reporter assay.” WT, ΔIRAK1, ΔIRAK4, and ΔMYD88 cell lines were all tested in this manner. All plasmids were sequence verified by complete plasmid sequencing on the Ion Torrent S5 platform at the UNC Lineberger Vironomics Core (https://www.med.unc.edu/vironomics/).

Inhibitor EC50 assays.

For generating IRAK, NF-κB, BTK, and MYD88 inhibitor EC50 values, serial dilutions of the inhibitors were added to 96-well plates containing 5,000 cells per well and incubated for 48 h. After 48 h, cell viability assays were carried out using CellTiter-Glo 2.0 luminescent cell viability assay (Promega, G9242) per manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was measured at 560 nm using the FLUOstar Optima (BMG Lab Tech). EC50 values were calculated using the R package DRC (version 3.5.3). Inhibitors used in this study were as follows: Inh1 (CAS number [no.] 1042224-63-4), Inh2 (CAS no. 928333-30-6), Inh3 (CAS no. 1012343-93-9), Inh4 (CAS no. 1012104-68-5), Inh6 (CAS no. 1042672-97-8), Inh1-4 (CAS no. 509093-47-4), BAY11 (CAS no. 19542-67-7), ST2825 (CAS no. 894787-30-5), acalabrutinib (CAS no. 1420477-60-6), AVL-292 (CAS no. 1202757-89-8), and ibrutinib (CAS no.936563-96-1).

Inhibitor KINOMEscan.

We obtained KINOMEscan profiles from DiscoverX-Eurofins for each of the six IRAK inhibitors used in this study, which screened each inhibitor at 50 and 250 nM concentrations against 480 human kinases. From this profiling, we were able to generate specific kinase profiles for each inhibitor.

RNA-sequencing analysis.

One million cells were harvested, flash frozen in TRIzol (Invitrogen, 15596026), and shipped on dry ice to Novogene for Illumina-based RNA-sequencing. Raw sequence data fastq files were imported into CLC genomics workbench (Qiagen, version 12). Read alignment was performed using default parameters, where reads were annotated by their genes as well as transcripts from annotations on Homo sapiens (hg38) sequence mRNA. The resultant gene expression (GE) tracks were used as input for further analysis and to generate figures in R (version 3.5.3 [2019-03-11]) and Bioconductor v3.10 using DESeq2 (69). Heat maps illustrating the gene expression for the WT and clones treated with IL-1β and IL-1β plus inhibitors were generated on CLC genomics, using the GE tracks as input. The hierarchical clustering was performed by measuring the Euclidean distance between clusters, which were defined by their average linkage. Filtering was performed based on a fixed number of features, with a minimum of 10 and a maximum of 100 genes. All reads were submitted to SRA under accession number PRJNA590509.

Exome sequencing and mutation calling analysis.

DNA was extracted from 1 million cells using a MagNA Pure Compact nucleic acid isolation I large-volume kit (Roche 3730972001) and quantitated by Qubit 3.0 double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) high-sensitivity (HS) assay (Life Technologies). Barcoded exome sequencing libraries were prepared from 100 ng DNA according to the Life Technologies protocol MAN00009808 rev. A.0. with an Ion AmpliSeq Exome RDY library preparation kit (Life Technologies, A38262) (63). Samples were sequenced on the Ion S5 system using methods as previously reported (63). The SRA accession number is PRJNA596731.

Statistics.

Colony formation count data were transformed to the square root of the total number of colonies. The square root transformation is a variance-stabilizing transformation for Poisson-distributed random samples. A Tukey’s posttest was run on count data to obtain significance and confidence intervals for the data and to adjust for multiple comparisons. All calculations were performed using R version 3.5.3 (2019-03-11). Data and code are available at https://bitbucket.org/ddittmer/r_irak2019/src/master/.

Data availability.

RNA-seq data for WT and IRAK4 knockout cells are available in the BioProject database under accession number PRJNA590509. The Exome-seq data of the IRAK pathway knockout cells are available in BioProject under accession number PRJNA596731. R was used for RNA-seq analysis and the volcano plots. All of the code used in this study was deposited at https://bitbucket.org/ddittmer/r_irak2019/src/master/.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by Public Health Service grants CA239583 and CA019014 to D.P.D.

We thank Tischan Seltzer and Kaitlin Porter for proofreading the manuscript, Carolina Caro-Vegas and Tiphaine Calabre for expertise in ELISAs, all of the members of the UNC Vironomics Core (https://www.med.unc.edu/vironomics/) and Femi Villamor for sequencing and KSHV viral load assays, and all members of the Dittmer and Damania labs for comments and suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang LW, Shen H, Nobre L, Ersing I, Paulo JA, Trudeau S, Wang Z, Smith NA, Ma Y, Reinstadler B, Nomburg J, Sommermann T, Cahir-McFarland E, Gygi SP, Mootha VK, Weekes MP, Gewurz BE. 2019. Epstein-Barr-virus-induced one-carbon metabolism drives B cell transformation. Cell Metab 30:539.e11–555.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panea RI, Love CL, Shingleton JR, Reddy A, Bailey JA, Moormann AM, Otieno JA, Ong'echa JM, Oduor CI, Schroeder KMS, Masalu N, Chao NJ, Agajanian M, Major MB, Fedoriw Y, Richards KL, Rymkiewicz G, Miles RR, Alobeid B, Bhagat G, Flowers CR, Ondrejka SL, Hsi ED, Choi WWL, Au-Yeung RKH, Hartmann W, Lenz G, Meyerson H, Lin Y-Y, Zhuang Y, Luftig MA, Waldrop A, Dave T, Thakkar D, Sahay H, Li G, Palus BC, Seshadri V, Kim SY, Gascoyne RD, Levy S, Mukhopadyay M, Dunson DB, Dave SS. 2019. The whole-genome landscape of Burkitt lymphoma subtypes. Blood 134:1598–1607. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019001880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dittmer DP, Damania B. 2016. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: immunobiology, oncogenesis, and therapy. J Clin Invest 126:3165–3175. doi: 10.1172/JCI84418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. 1995. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med 332:1186–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renne R, Zhong W, Herndier B, McGrath M, Abbey N, Kedes D, Ganem D. 1996. Lytic growth of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat Med 2:342–346. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makgoeng SB, Bolanos RS, Jeon CY, Weiss RE, Arah OA, Breen EC, Martinez-Maza O, Hussain SK. 2018. Markers of immune activation and inflammation, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2:pky082. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pky082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epeldegui M, Lee JY, Martinez AC, Widney DP, Magpantay LI, Regidor D, Mitsuyasu R, Sparano JA, Ambinder RF, Martinez-Maza O. 2016. Predictive value of cytokines and immune activation biomarkers in AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with rituximab plus infusional EPOCH (AMC-034 trial). Clin Cancer Res 22:328–336. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polizzotto MN, Uldrick TS, Wang V, Aleman K, Wyvill KM, Marshall V, Pittaluga S, O'Mahony D, Whitby D, Tosato G, Steinberg SM, Little RF, Yarchoan R. 2013. Human and viral interleukin-6 and other cytokines in Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Blood 122:4189–4198. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-519959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brockmeyer NH, Willers CP, Anders S, Mertins L, Rockstroh JK, Sturzl M. 1999. Cytokine profile of HIV-positive Kaposi’s sarcoma derived cells in vitro. Eur J Med Res 4:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ensoli B, Nakamura S, Salahuddin SZ, Biberfeld P, Larsson L, Beaver B, Wong-Staal F, Gallo RC. 1989. AIDS-Kaposi’s sarcoma-derived cells express cytokines with autocrine and paracrine growth effects. Science 243:223–226. doi: 10.1126/science.2643161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssens S, Beyaert R. 2002. A universal role for MyD88 in TLR/IL-1R-mediated signaling. Trends Biochem Sci 27:474–482. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janssens S, Beyaert R. 2003. Functional diversity and regulation of different interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family members. Mol Cell 11:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottipati S, Rao NL, Fung-Leung WP. 2008. IRAK1: a critical signaling mediator of innate immunity. Cell Signal 20:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motshwene PG, Moncrieffe MC, Grossmann JG, Kao C, Ayaluru M, Sandercock AM, Robinson CV, Latz E, Gay NJ. 2009. An oligomeric signaling platform formed by the Toll-like receptor signal transducers MyD88 and IRAK-4. J Biol Chem 284:25404–25411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang D, Chen W, Xiong J, Sherrod CJ, Henry DH, Dittmer DP. 2014. Interleukin 1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) mutation is a common, essential driver for Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E4762–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405423111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawagoe T, Sato S, Matsushita K, Kato H, Matsui K, Kumagai Y, Saitoh T, Kawai T, Takeuchi O, Akira S. 2008. Sequential control of Toll-like receptor-dependent responses by IRAK1 and IRAK2. Nat Immunol 9:684–691. doi: 10.1038/ni.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singer JW, Fleischman A, Al-Fayoumi S, Mascarenhas JO, Yu Q, Agarwal A. 2018. Inhibition of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) as a therapeutic strategy. Oncotarget 9:33416–33439. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deguine J, Barton GM. 2014. MyD88: a central player in innate immune signaling. F1000Prime Rep 6:97. doi: 10.12703/P6-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui W, Xiao N, Xiao H, Zhou H, Yu M, Gu J, Li X. 2012. Beta-TrCP-mediated IRAK1 degradation releases TAK1-TRAF6 from the membrane to the cytosol for TAK1-dependent NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cell Biol 32:3990–4000. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00722-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang YS, Misior A, Li LW. 2005. Novel role and regulation of the interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK) family proteins. Cell Mol Immunol 2:36–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhyasen GW, Bolanos L, Fang J, Jerez A, Wunderlich M, Rigolino C, Mathews L, Ferrer M, Southall N, Guha R, Keller J, Thomas C, Beverly LJ, Cortelezzi A, Oliva EN, Cuzzola M, Maciejewski JP, Mulloy JC, Starczynowski DT. 2013. Targeting IRAK1 as a therapeutic approach for myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer Cell 24:90–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jain A, Kaczanowska S, Davila E. 2014. IL-1 receptor-associated kinase signaling and its role in inflammation, cancer progression, and therapy resistance. Front Immunol 5:553. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honda K, Yanai H, Mizutani T, Negishi H, Shimada N, Suzuki N, Ohba Y, Takaoka A, Yeh WC, Taniguchi T. 2004. Role of a transductional-transcriptional processor complex involving MyD88 and IRF-7 in Toll-like receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:15416–15421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406933101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Tassell BW, Seropian IM, Toldo S, Salloum FN, Smithson L, Varma A, Hoke NN, Gelwix C, Chau V, Abbate A. 2010. Pharmacologic inhibition of myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) prevents left ventricular dilation and hypertrophy after experimental acute myocardial infarction in the mouse. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 55:385–390. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181d3da24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ngo VN, Young RM, Schmitz R, Jhavar S, Xiao W, Lim KH, Kohlhammer H, Xu W, Yang Y, Zhao H, Shaffer AL, Romesser P, Wright G, Powell J, Rosenwald A, Muller-Hermelink HK, Ott G, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM, Rimsza LM, Campo E, Jaffe ES, Delabie J, Smeland EB, Fisher RI, Braziel RM, Tubbs RR, Cook JR, Weisenburger DD, Chan WC, Staudt LM. 2011. Oncogenically active MYD88 mutations in human lymphoma. Nature 470:115–119. doi: 10.1038/nature09671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruno A, Boisselier B, Labreche K, Marie Y, Polivka M, Jouvet A, Adam C, Figarella-Branger D, Miquel C, Eimer S, Houillier C, Soussain C, Mokhtari K, Daveau R, Hoang-Xuan K. 2014. Mutational analysis of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Oncotarget 5:5065–5075. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez-Aguilar A, Idbaih A, Boisselier B, Habbita N, Rossetto M, Laurenge A, Bruno A, Jouvet A, Polivka M, Adam C, Figarella-Branger D, Miquel C, Vital A, Ghesquieres H, Gressin R, Delwail V, Taillandier L, Chinot O, Soubeyran P, Gyan E, Choquet S, Houillier C, Soussain C, Tanguy ML, Marie Y, Mokhtari K, Hoang-Xuan K. 2012. Recurrent mutations of MYD88 and TBL1XR1 in primary central nervous system lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res 18:5203–5211. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G, Zhou Y, Liu X, Cao Y, Sheehy P, Manning RJ, Patterson CJ, Tripsas C, Arcaini L, Pinkus GS, Rodig SJ, Sohani AR, Harris NL, Laramie JM, Skifter DA, Lincoln SE, Hunter ZR. 2012. MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med 367:826–833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonzheim I, Giese S, Deuter C, Susskind D, Zierhut M, Waizel M, Szurman P, Federmann B, Schmidt J, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Coupland SE, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Fend F. 2015. High frequency of MYD88 mutations in vitreoretinal B-cell lymphoma: a valuable tool to improve diagnostic yield of vitreous aspirates. Blood 126:76–79. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-620518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubois S, Viailly PJ, Bohers E, Bertrand P, Ruminy P, Marchand V, Maingonnat C, Mareschal S, Picquenot JM, Penther D, Jais JP, Tesson B, Peyrouze P, Figeac M, Desmots F, Fest T, Haioun C, Lamy T, Copie-Bergman C, Fabiani B, Delarue R, Peyrade F, Andre M, Ketterer N, Leroy K, Salles G, Molina TJ, Tilly H, Jardin F. 2017. Biological and clinical relevance of associated genomic alterations in MYD88 L265P and non-L265P-mutated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: analysis of 361 cases. Clin Cancer Res 23:2232–2244. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loiarro M, Capolunghi F, Fanto N, Gallo G, Campo S, Arseni B, Carsetti R, Carminati P, De Santis R, Ruggiero V, Sette C. 2007. Pivotal advance: inhibition of MyD88 dimerization and recruitment of IRAK1 and IRAK4 by a novel peptidomimetic compound. J Leukoc Biol 82:801–810. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1206746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fanto N, Gallo G, Ciacci A, Semproni M, Vignola D, Quaglia M, Bombardi V, Mastroianni D, Zibella MP, Basile G, Sassano M, Ruggiero V, De Santis R, Carminati P. 2008. Design, synthesis, and in vitro activity of peptidomimetic inhibitors of myeloid differentiation factor 88. J Med Chem 51:1189–1202. doi: 10.1021/jm070723u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang N, Han X, Liu H, Zhao T, Li J, Feng Y, Mi X, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Wang X. 2017. Myeloid differentiation factor 88 is up-regulated in epileptic brain and contributes to experimental seizures in rats. Exp Neurol 295:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelly PN, Romero DL, Yang Y, Shaffer AL, Chaudhary D, Robinson S, Miao W, Rui L, Westlin WF, Kapeller R, Staudt LM. 2015. Selective interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 inhibitors for the treatment of autoimmune disorders and lymphoid malignancy. J Exp Med 212:2189–2201. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan W, Bubman D, Chadburn A, Harrington WJ Jr, Cesarman E, Knowles DM. 2005. Distinct subsets of primary effusion lymphoma can be identified based on their cellular gene expression profile and viral association. J Virol 79:1244–1251. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1244-1251.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu P, Yang C, Guasparri I, Harrington W, Wang YL, Cesarman E. 2009. Early events of B-cell receptor signaling are not essential for the proliferation and viability of AIDS-related lymphoma. Leukemia 23:807–810. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klein U, Gloghini A, Gaidano G, Chadburn A, Cesarman E, Dalla-Favera R, Carbone A. 2003. Gene expression profile analysis of AIDS-related primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) suggests a plasmablastic derivation and identifies PEL-specific transcripts. Blood 101:4115–4121. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gregory SM, West JA, Dillon PJ, Hilscher C, Dittmer DP, Damania B. 2009. Toll-like receptor signaling controls reactivation of KSHV from latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:11725–11730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905316106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen LE, Whitehead AS. 2001. IRAK1b, a novel alternative splice variant of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK), mediates interleukin-1 signaling and has prolonged stability. J Biol Chem 276:29037–29044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akdis M, Aab A, Altunbulakli C, Azkur K, Costa RA, Crameri R, Duan S, Eiwegger T, Eljaszewicz A, Ferstl R, Frei R, Garbani M, Globinska A, Hess L, Huitema C, Kubo T, Komlosi Z, Konieczna P, Kovacs N, Kucuksezer UC, Meyer N, Morita H, Olzhausen J, O'Mahony L, Pezer M, Prati M, Rebane A, Rhyner C, Rinaldi A, Sokolowska M, Stanic B, Sugita K, Treis A, van de Veen W, Wanke K, Wawrzyniak M, Wawrzyniak P, Wirz OF, Zakzuk JS, Akdis CA. 2016. Interleukins (from IL-1 to IL-38), interferons, transforming growth factor beta, and TNF-alpha: receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 138:984–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knop J, Martin MU. 1999. Effects of IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) expression on IL-1 signaling are independent of its kinase activity. FEBS Lett 448:81–85. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamin TT, Miller DK. 1997. The interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase is degraded by proteasomes following its phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 272:21540–21547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ntoufa S, Vilia MG, Stamatopoulos K, Ghia P, Muzio M. 2016. Toll-like receptors signaling: a complex network for NF-kappaB activation in B-cell lymphoid malignancies. Semin Cancer Biol 39:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao N, Nguyen S, Ngo K, Fung-Leung WP. 2005. A novel splice variant of interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R)-associated kinase 1 plays a negative regulatory role in Toll/IL-1R-induced inflammatory signaling. Mol Cell Biol 25:6521–6532. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6521-6532.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maschera B, Ray K, Burns K, Volpe F. 1999. Overexpression of an enzymically inactive interleukin-1-receptor-associated kinase activates nuclear factor-kappaB. Biochem J 339:227–231. doi: 10.1042/bj3390227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shiratori E, Itoh M, Tohda S. 2017. MYD88 inhibitor ST2825 suppresses the growth of lymphoma and leukaemia cells. Anticancer Res 37:6203–6209. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weber ANR, Cardona Gloria Y, Cinar O, Reinhardt HC, Pezzutto A, Wolz OO. 2018. Oncogenic MYD88 mutations in lymphoma: novel insights and therapeutic possibilities. Cancer Immunol Immunother 67:1797–1807. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2242-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feng Y, Duan W, Cu X, Liang C, Xin M. 2019. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors in treating cancer: a patent review (2010–2018). Expert Opin Ther Pat 29:217–241. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2019.1594777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Powers JP, Li S, Jaen JC, Liu J, Walker NP, Wang Z, Wesche H. 2006. Discovery and initial SAR of inhibitors of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-4. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 16:2842–2845. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sin SH, Roy D, Wang L, Staudt MR, Fakhari FD, Patel DD, Henry D, Harrington WJ Jr, Damania BA, Dittmer DP. 2007. Rapamycin is efficacious against primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cell lines in vivo by inhibiting autocrine signaling. Blood 109:2165–2173. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caro-Vegas C, Sellers S, Host KM, Seltzer J, Landis J, Fischer WA 2nd, Damania B, Dittmer DP. 2020. Runaway Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus replication correlates with systemic IL-10 levels. Virology 539:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Godfrey A, Anderson J, Papanastasiou A, Takeuchi Y, Boshoff C. 2005. Inhibiting primary effusion lymphoma by lentiviral vectors encoding short hairpin RNA. Blood 105:2510–2518. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faure A, Hayes M, Sugden B. 2019. How Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus stably transforms peripheral B cells towards lymphomagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:16519–16528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905025116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bigi R, Landis JT, An H, Caro-Vegas C, Raab-Traub N, Dittmer DP. 2018. Epstein-Barr virus enhances genome maintenance of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E11379–E11387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1810128115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roy D, Sin SH, Damania B, Dittmer DP. 2011. Tumor suppressor genes FHIT and WWOX are deleted in primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cell lines. Blood 118:e32–e39. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-323659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luan SL, Boulanger E, Ye H, Chanudet E, Johnson N, Hamoudi RA, Bacon CM, Liu H, Huang Y, Said J, Chu P, Clemen CS, Cesarman E, Chadburn A, Isaacson PG, Du MQ. 2010. Primary effusion lymphoma: genomic profiling revealed amplification of SELPLG and CORO1C encoding for proteins important for cell migration. J Pathol 222:166–179. doi: 10.1002/path.2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abeykoon JP, Paludo J, King RL, Ansell SM, Gertz MA, LaPlant BR, Halvorson AE, Gonsalves WI, Dingli D, Fang H, Rajkumar SV, Lacy MQ, He R, Kourelis T, Reeder CB, Novak AJ, McPhail E, Viswanatha D, Witzig TE, Go RS, Habermann T, Buadi FK, Dispenzieri A, Leung N, Lin Y, Thompson C, Hayman S, Kyle RA, Kumar S, Kapoor P. 2017. Impact of MYD88 mutation status in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Am J Hematol 93:187–194. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alegria V, Prieto-Torres L, Santonja C, Cordoba R, Manso R, Requena L, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM. 2017. MYD88 L265P mutation in cutaneous involvement by Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. J Cutan Pathol 44:625–631. doi: 10.1111/cup.12944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manzano M, Patil A, Waldrop A, Dave SS, Behdad A, Gottwein E. 2018. Gene essentiality landscape and druggable oncogenic dependencies in herpesviral primary effusion lymphoma. Nat Commun 9:3263. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05506-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matta H, Chaudhary PM. 2004. Activation of alternative NF-kappa B pathway by human herpes virus 8-encoded Fas-associated death domain-like IL-1 beta-converting enzyme inhibitory protein (vFLIP). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:9399–9404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308016101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grossmann C, Podgrabinska S, Skobe M, Ganem D. 2006. Activation of NF-kappaB by the latent vFLIP gene of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is required for the spindle shape of virus-infected endothelial cells and contributes to their proinflammatory phenotype. J Virol 80:7179–7185. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01603-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ballon G, Chen K, Perez R, Tam W, Cesarman E. 2011. Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) vFLIP oncoprotein induces B cell transdifferentiation and tumorigenesis in mice. J Clin Invest 121:1141–1153. doi: 10.1172/JCI44417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caro-Vegas C, Bailey A, Bigi R, Damania B, Dittmer DP. 2019. Targeting mTOR with MLN0128 overcomes rapamycin and chemoresistant primary effusion lymphoma. mBio 10:e02871-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02871-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sarosiek KA, Cavallin LE, Bhatt S, Toomey NL, Natkunam Y, Blasini W, Gentles AJ, Ramos JC, Mesri EA, Lossos IS. 2010. Efficacy of bortezomib in a direct xenograft model of primary effusion lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:13069–13074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002985107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cornali E, Zietz C, Benelli R, Weninger W, Masiello L, Breier G, Tschachler E, Albini A, Stürzl M. 1996. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates angiogenesis and vascular permeability in Kaposi’s sarcoma. Am J Pathol 149:1851–1869. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang J, Renne R, Dittmer D, Ganem D. 2000. Inflammatory cytokines and the reactivation of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic replication. Virology 266:17–25. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu G, Tsuruta Y, Gao Z, Park YJ, Abraham E. 2007. Variant IL-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 mediates increased NF-kappa B activity. J Immunol 179:4125–4134. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Han TU, Cho SK, Kim T, Joo YB, Bae SC, Kang C. 2013. Association of an activity-enhancing variant of IRAK1 and an MECP2-IRAK1 haplotype with increased susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 65:590–598. doi: 10.1002/art.37804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq data for WT and IRAK4 knockout cells are available in the BioProject database under accession number PRJNA590509. The Exome-seq data of the IRAK pathway knockout cells are available in BioProject under accession number PRJNA596731. R was used for RNA-seq analysis and the volcano plots. All of the code used in this study was deposited at https://bitbucket.org/ddittmer/r_irak2019/src/master/.