Abstract

Introduction

Medical pluralism, or concurrent utilisation of multiple therapeutic modalities, is common in various international contexts, and has been characterised as a factor contributing to poor health outcomes in low-resource settings. Traditional healers are ubiquitous providers in most regions, including the study site of southwestern Uganda. Where both informal and formal healthcare services are both available, patients do not engage with both options equally. It is not well understood why patients choose to engage with one healthcare modality over the other. The goal of this study was to explain therapeutic itineraries and create a conceptual framework of pluralistic health behaviour.

Methods

In-depth interviews were conducted from September 2017 to February 2018 with patients seeking care at traditional healers (n=30) and at an outpatient medicine clinic (n=30) in Mbarara, Uganda; the study is nested within a longitudinal project examining HIV testing engagement among traditional healer-using communities. Inclusion criteria included age ≥18 years, and ability to provide informed consent. Participants were recruited from practices representing the range of healer specialties. Following an inductive approach, interview transcripts were reviewed and coded to identify conceptual categories explaining healthcare utilisation.

Results

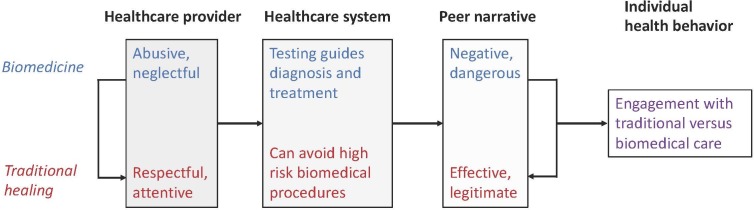

We identified three broad categories relevant to healthcare utilisation: (1) traditional healers treat patients with ‘care’; (2) biomedicine uses ‘modern’ technologies and (3) peer ‘testimony’ influences healthcare engagement. These categories describe variables at the healthcare provider, healthcare system and peer levels that interrelate to motivate individual engagement in pluralistic health resources.

Conclusions

Patients perceive clear advantages and disadvantages to biomedical and traditional care in medically pluralistic settings. We identified factors at the healthcare provider, healthcare system and peer levels which influence patients’ therapeutic itineraries. Our findings provide a basis to improve health outcomes in medically pluralistic settings, and underscore the importance of recognising traditional healers as important stakeholders in community health.

Keywords: complementary medicine, international health services, qualitative research, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study illuminates factors that motivate engagement with healthcare resources by using data from biomedical and traditional medicine utilisers.

This study employed qualitative methods to explore participants’ own experiences of healthcare modalities, and identify perceived advantages and disadvantages of each form of healing.

While the data gathered are highly contextual and specific to the study context, the conceptual model presented offers a broad application to other medically pluralistic communities.

This conceptual model could be used to guide healthcare initiatives, policies and research in pluralistic settings.

Introduction

Medical pluralism, or utilisation of multiple therapeutic modalities, is common where both biomedical and complementary or alternative treatments are available to patients. This pattern of healthcare engagement is observed in both high-resource1 2 and low-resource settings,3–6 and is well described for patients with both acute7–9 and chronic illness10–13 in various international contexts. In low-income and middle-income countries, complementary and alternative healthcare services are often provided by traditional healers, who practice outside of the formal biomedical system. Traditional healers are broadly defined by WHO as: (1) persons recognised by local community as healers; (2) having regular patient attendance and (3) having space to receive and treat patients.14 They ‘provide healthcare by using plant, animal and mineral substances, and other methods based on social, cultural and religious practices’.14 It is estimated that 80% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa visit traditional healers.5

As such, traditional healers are an initial point of contact for patients in medically pluralistic settings. Patients may prefer informal health services from traditional healers because of their increased accessibility: healers are present in higher numbers than physicians and biomedical facilities, particularly in low-resource settings.5 However, their popularity cannot be strictly explained by convenience. Research in urban regions having high density of biomedical institutions demonstrates similar reliance on traditional healers.1 3 Patients may also seek out traditional therapies to address symptoms attributed to ancestral curses or bewitching, believed incurable by biomedicine.15 Use of traditional medicine is also strongly tied to local religious and ethnic identities.16 Patients may pursue traditional healing in the setting of biomedicine treatment ‘failure’, when symptoms worsen or persist despite ongoing therapies.6 17 18

Prior research has shown that traditional healer use is a factor contributing to poor health outcomes among patients. For example, receiving care from a traditional healer has been shown to delay HIV testing and antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation,19 and interrupt HIV treatment18 for people living with HIV (PLHIV). In Mozambique, PLHIV initially seeking care from traditional healers experienced significantly longer delays to diagnosis compared with those who did not use healers; this delay exponentially grew with corresponding increases in the number of healers consulted prior to receiving HIV testing.19 In South Africa, medical pluralism was shown to be negatively associated with ART use in a cohort of PLHIV.20 Use of traditional healers was also identified as an important variable contributing to the recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa.21 Studies have demonstrated that medical pluralism similarly contributes to poor outcomes for non-infectious diseases, such as non-adherence to chemotherapy for cancer,4 22 or poor outpatient linkage to care for patients with hypertension.12

Because they are frequently consulted for most types of illness, traditional healers could be important allies for public health initiatives. Some programmes have attempted to engage with healers for these purposes, which have included trainings for healers to deliver counselling and facility referral for HIV,23 24 tuberculosis25 or malaria testing,7 or to increase uptake of prenatal care26 and mental health treatment.27 However, in most cases, programme effectiveness has been limited by the fact that patients may not complete referrals to facilities. These findings highlight the fact that where both informal and formal healthcare services are available, patients do not engage with both options equally.

There remains a critical lack of understanding about why patients choose to use one healthcare resource, but not another. It is clear that biomedicine and traditional healing offer distinctive forms of healthcare for patients. But there is a dearth of knowledge on perceived advantages and disadvantages of each modality from the perspective of the healthcare user. Without this information, healthcare initiatives in pluralistic settings cannot be truly ‘patient centred’, and are at risk for failure. The goal of this study was to identify factors that motivate engagement with healthcare resources in a sub-Saharan African context, using qualitative research methods. We sought to explain therapeutic itineraries by conducting interviews with users of biomedical and traditional healthcare resources. These data were used to develop a general, conceptual framework that can inform future work in similar medically pluralistic settings.

Methods

Study setting and design

This qualitative study was conducted in Mbarara District, Uganda, a rural district of 418 000 residents located ~275 km southwest of the capital city of Kampala. Southwestern Uganda is a medically pluralistic context, where both traditional and biomedical modalities of healthcare coexist.28–30

WHO defines ‘traditional medicine practices’ to include both medication and procedure-based treatments, including use of herbal remedies, manual physical manipulation and spiritual therapies.5 14 The scope of treatments delivered by healers throughout the world varies by location. In Uganda, traditional healers practise herbalism and spiritual healing31; they also set broken bones32 and attend births in the community.33 Spiritual healers attribute their powers to the Bachwezi, which are believed to be ancestral spirits from an ancient kingdom that previously occupied this region of eastern Africa.34 35 For the purposes of this study, we excluded Christian or Muslim spiritual healers (ie, ‘Born Again’ or Pentecostal ministries), which have been extensively studied in sub-Saharan Africa as ‘faith healers’.18 36 In Uganda, traditional healing is not formally recognised by the Ministry of Health; there is no centralised oversight of traditional healing training programmes or services. This research was conducted as part of a multiyear, mixed methods study of HIV services engagement in a medically pluralistic community.

Sampling and recruitment

Following a purposive sampling strategy, 60 adults were identified to participate as key informants in this study, or ‘individuals that are especially knowledgeable about or experienced with a phenomenon of interest’.37 In our case, key informants were selected to represent variation in experiences of receiving modalities of healthcare: biomedical and traditional. That is, participants were patients representing two subgroups: (1) individuals receiving treatment from traditional healers (n=30), and (2) individuals receiving treatment from a biomedical general medicine outpatient clinic (n=30). Inclusion criteria for all participants were: (1) age ≥18 years; (2) ability to provide informed consent and (3) seeking healthcare at either a traditional healer or outpatient biomedical clinic in Mbarara District.

Both verbal and written informed consents were obtained by Ugandan research assistants (RAs) prior to enrolment. After verbally reviewing the consent form, research staff used a 5-item questionnaire to assess whether the potential participant understood the study and consent process. This questionnaire posed questions critical to demonstrating consent, such as ‘How much time will this take you?’; ‘What are the possible benefits for you?’. If a potential participant demonstrated errors in understanding, these were corrected, and potential participants asked if they needed further clarification. If, after further attempts to clarify misunderstandings, study staff determined that the potential participant did not comprehend the consent process, or critical aspects of the study, they were not enrolled.

Participants in the traditional medicine subgroup were recruited from 12 traditional healer practices which reflected the range of healer specialties present in the study region: herbalist, bone setter, traditional birth attendant and spiritual healer. All were located within 20 km of Mbarara town centre. It is well established that men tend to have low uptake of in-healthcare services in sub-Saharan Africa.38–40 In order to ensure that male perspectives were represented, we recruited two-thirds of participants at healer practices who were known to provide services for men. Therefore, more bonesetter and spiritual healer patients are included in the traditional healer group. Participants in the biomedical subgroup were recruited from Mbarara Municipality Clinic, a general outpatient government-run clinic in the town of Mbarara, which serves approximately 50 000 patients per year. Services at this clinic are provided free of charge.

At both traditional and biomedical facilities, RAs approached patients following completion of visits to assess eligibility and interest in participation. Potential participants were individually recruited by RAs, who visited recruitment sites once per week during business hours to screen for eligible patients. Recruitment visits were scheduled on random days of the week to maximise variation of participants included in this study. A maximum of two participants was enrolled during each site visit in order to allow ample time to review informed consent and conduct minimally structured interviews. This approach ensured interview quality, and was central to the inductive data analysis process by providing time to review interview content, provide feedback to RAs and identify preliminary codes (see the Data collection and Analysis of data sections for more details). Biomedical clinic leadership and traditional healers gave permission for study staff to recruit patients at their practices. Recruitment was carried out over a period of 6 months (September 2017–February 2018).

A target sample size of 30 participants per subgroup was guided by prior research suggesting that a range between 20 and 30 interviews is adequate to reach thematic saturation, the point at which no new concepts emerge from subsequent interviews.41–43 After 30 interviews per group were conducted, the study authors agreed that thematic saturation had been reached, and interview content no longer contained new or surprising content.

Data collection

Three Ugandan RAs, two women and one man, with prior experience in conducting qualitative interviews in southwestern Uganda collected data for this study. Prior to initiation of data collection, all RAs took part in a 3-day training session led by RS and JM-A, which focused on the principles of qualitative research, approaches to conducting high-quality interviews and establishing standard procedures for interview translation and transcription. In addition, the RAs underwent intensive training with interview guide questions to ensure consistency of delivery and use throughout the study.

Each study participant took part in a single, individual, in-depth interview with one of these RAs. Interviews were conducted following an interview guide that included the following topics: (1) details of the patient’s therapeutic itinerary for his/her current symptoms; (2) symptoms that motivated him/her to seek healthcare; (3) attitudes towards, and experiences with, traditional and biomedicine; and (4) details of concurrent or recent biomedical and traditional healer visits. The interview guide was created in English, translated to the local language (Runyankore) and back-translated into English to verify preservation of meaning. In addition, the interview guide was piloted with three traditional healers prior to initiation of data collection in August 2017; these responses were not included in our analysis.

Interviews lasted approximately 1 hour and were conducted in the local language (Runyankore), in private locations at either healer practices or at the participating biomedical clinic. Participants received the equivalent of 10 000 Ugandan Shillings (UGX, ~US$3) in household staples (cooking oil, sugar, salt, soap) in recognition of the time and effort required to participate in the interview.

Interviews were digitally recorded, then transcribed and translated into English by the same RA who had conducted the interview. All transcripts were produced within 72 hours of the interview being completed. The transcripts were reviewed line by line by the first author for quality, content and to provide feedback to the RAs regarding strategies to improve interviewing techniques. This monitoring process allowed for RAs to receive consistent feedback to improve interviewing skills to ensure that interviews were consistently high quality, explored participants unique experiences and focused on interview guide topics across interviewers. Though some variation is expected in qualitative interview data, we maximised the validity of our data by continuing enrolment until thematic saturation was reached in each participant group (see the Sampling and recruitment section). English transcripts were spot checked against audio recordings by an author (JM-A, who is fluent in Runyankore and English) to ensure validity and integrity of translations.

Analysis of data

A three-step, inductive approach was used to analyse the qualitative data, as follows: (1) development of codes; (2) coding and (3) category construction. We employed an interpretive phenomenological approach to data analysis,44 45 as the goal of this study was to explore participants’ own experiences and perspectives on healthcare engagement.

Development of codes

Two authors (RS and JM-A) reviewed transcripts within 72 hours of completion and corresponded weekly to identify and discuss emerging concepts. Guided by these discussions, the first author (RS) produced an initial set of codes, or labels that described key concepts in the dataset. Using an inductive strategy, this process was conducted while interviews were ongoing, providing overlap between qualitative interviewing and data analysis, allowing for iterative engagement with the dataset to identify concepts of interest. As additional transcripts were produced and reviewed, codes were reviewed and refined to fit the data. Using the ‘constant comparison’ method, newly coded text segments were compared with text segments previously marked with the same code to determine if they reflected the same concept.46 This process was repeated until all transcripts had been reviewed. A final list of codes was produced through discussion and consensus among three coauthors (RS, JM-A and RK).

Coding

All study transcripts were coded, and recoded when necessary, using the finalised list of codes. QSR NViVo V.11 (QRS International Pty) was used for coding and data organisation, but not in development of codes.

Category construction

Next, coded data were examined and grouped to form conceptual categories, where data are aggregated based on similarities of meaning. Categories are defined below using text examples. Quotes from participants are shown as italicised and indented. Inter-relationships between categories were identified to create a conceptual framework illustrating factors that influence health behaviour in a pluralistic context (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model showing key factors within various levels (healthcare provider, healthcare system, peer) influencing individual health behaviour within medically pluralistic contexts. Each factor differentially influences an individual’s therapeutic itinerary. Negative factors may motivate a switch to the other modality, and positive factors contribute towards continued use of a particular healthcare modality. This model is not inclusive of all variables that influence health engagement, but illustrates categories that were described by our participants in driving their healthcare decision-making, specifically regarding decisions to use traditional or biomedical care.

Patient and public involvement

Patients receiving healthcare from traditional healers and at a public biomedical facility were involved as participants in this study. Participants provided written and verbal informed consent in Runyankore.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Characteristics of study participants appear in table 1. Over half of the sample had clinical experience with both biomedical and traditional modalities of healthcare. However, pluralistic behaviours were much more commonly reported among patients of traditional healers. Only two participants recruited from the biomedical clinic reported prior experience receiving care from traditional healers (n=2/30, 7%); in contrast, all (n=30) traditional healer patients reported prior experience receiving biomedical treatment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | Traditional healer clients (n=30) | Biomedical clients (n=30) |

| Report previously receiving care from alternate modality | n=30 (100%) | n=2 (7%) |

| Age (in years) | 30 (median) IQR=20 |

28.5 (median) IQR=10.75 |

| Female gender (%) | n=16 (53%) | n=18 (60%) |

| Primary school education or less | n=14 (47%) | n=13 (43%) |

| Household size (in persons) | 5 (median) IQR=3 |

4.5 (median) IQR=3.5 |

| Marital status | Single (n=7) Married/cohabiting (n=21) Widowed (n=2) |

Single (n=11) Married/cohabiting (n=17) Widowed (n=2) |

| Christian religion | n=25 (83%) | n=23 (77%) |

| Monthly household income (in USD) | US$41 (median), IQR=76 |

US$22 (median) IQR=46 |

| Type of healer visited on day of enrolment | Spiritualist (n=12) Bonesetter (n=10) Traditional birth attendant (n=4) Herbalist (n=4) |

Not applicable |

Participants recruited from healer practice locations were slightly older, with a higher proportion being married, and with higher reported monthly incomes, compared with the biomedicine group. Biomedical participants were recruited from a government-run medical clinic, where they received health services at no cost. Therefore, we would expect lower household incomes, as they have preferentially sought to receive free medical care, rather than present to a fee-for-service facility. Other characteristics, including gender, household size, highest level of education and religious affiliation, were similar between the two groups.

Qualitative results

Overview

Our qualitative data indicate important perceived advantages and disadvantages to both healthcare modalities, which motivate patient engagement with available resources. We have developed three broad categories representing influences on therapeutic itineraries that were evident in the data. They are summarised as follows: (1) traditional healers treat patients with ‘care’; (2) biomedicine uses ‘modern’ technologies; and (3) peer ‘testimony’ influences healthcare engagement. Within each of these categories, we provide examples to illustrate how these factors drive pluralistic healthcare engagement. We consider each one separately, below, and then present a conceptual model for how these factors interrelate to create therapeutic itineraries in southwestern Uganda.

Traditional healers care about their patients

Patients recruited from traditional healers report positive experiences with their care, specifically describing that treatments effectively relieve their symptoms. Participants state that they prefer traditional therapies because traditional practitioners ‘heal faster’. This efficient healing is sometimes attributed to the fact that traditional practitioners spend more time personally treating and caring for their patients, compared with healthcare workers in biomedical settings:

Those [bonesetters] are super! They heal faster than biomedicals. When you take your patient to a bonesetter, he does not take long to get healed, compared to one in the hospital. In hospitals, the healing process is long because they do not do much more than hanging you there [in traction] and leave you. You can even become lame because they do not check to see whether you are healing or not. But for the healer, he does his reviews [checks your wound healing] constantly. (Bonesetter patient, female)

Patients receiving traditional care also state that they are treated with respect, and that healers are motivated to care for patients, rather than being strictly economically driven. Participants reported that healers attend to patients immediately, even if they did not have money; a few participants stated that healers allowed them to pay for services rendered in instalments, or in kind (through farm goods). A participant seeking care from a traditional birth attendant described her preference for traditional healing, emphasising the kindness of her practitioner:

[The healer] does everything for you. Her services are excellent. In fact, when you deliver [your children] from here, you do not even think of going elsewhere another time. She cares so much about her clients. In fact, for all my pregnancies, I received antenatal care from this healer. She is my neighbor, and instead of going to sit at the hospital the whole day waiting for checkup, I come here. She is my neighbor and her services are good. So, I come get my antenatal checkup, and go back home to do my chores. (Traditional birth attendant patient, female)

In contrast, patients describe experiences with biomedicine with narratives of disrespect, mistreatment, neglect or ‘abuse’. The central message of these biomedical testimonies is that healthcare workers do not care about their patients. In some cases, participants referred to these accounts while explaining why they tend to avoid biomedical facilities. A woman describes her experience receiving antenatal care at the local hospital:

I came to this hospital for antenatal care and found a nurse who treated me badly. She would tell you to lay on the bed and instead of telling you what to do, she would shout at you and say, “Don’t face me! Face the other side!” in a loud voice, and you wonder what the problem was. She embarrassed me and I felt ashamed. I promised myself never to return in this hospital …. She would only shout at us. She was horrible. (Biomedical patient, female)

A number of participants describe experiences at biomedical facilities where they are never attended to by biomedical staff, despite waiting for many hours—sometimes spending the entire day without receiving medical attention. These hours spent waiting come at the expense of childcare, household duties and income-generating activities. One man describes his experience seeking biomedical care for a toothache as follows:

I went to the referral hospital and spent there the whole day without treatment. The following morning, when I went back, I was given only Panadol [Acetaminophen]. I felt so sad. (Biomedical patient, male)

Another patient states that he gave up after waiting all day for a voluntary circumcision procedure:

You reach there and sit for the whole day without treatment. Drugs are never there and health workers do not attend to patients as it should be. They arrive at work late and leave work early. They are really bad. I went [to the clinic] one time for circumcision and sat there for many hours until I got hungry and gave up. I left without seeing any doctor. (Bonesetter patient, male)

Biomedicine uses modern technologies to heal

Participants state that biomedical care is preferred in instances where modern technologies can be used to provide a diagnosis for one’s symptoms, and guide treatment. Through blood and radiological tests, healthcare providers can identify the specific cause of a patient’s illness, and provide appropriate care. Patients perceive that the information generated by biomedical technology validates the therapies administered to them:

They use machines to diagnose and test for conditions. The give the right medical information. (Biomedical patient, male).

Having received a specific diagnosis, participants also believe that the treatment recommended by healthcare workers will be effective in alleviating their symptoms. For example, one participant described how appropriate medicines have the capacity to heal, even if taken in small amounts:

When you come [to the clinic] you get diagnosed and they write for you a prescription and you get the medicine then their service is good … Even if you get very little medicine from them and take it, you get healed. (Biomedical patient, female)

Another patient explains why the capacity to intervene with modern biomedical technology is more effective in treating symptoms than traditional medicine:

Biomedical facilities are good … when you are, for instance, in a critical condition, they can put you on life support machines, or they can put you on a drip. They can also give you tablets and injections that can help you. Traditional healers can’t manage something like that. They don’t have modern equipment. They don’t have tablets, and they don’t have drips and injections. (Bonesetter patient, male)

Results from biomedical testing guide what some participants describe as ‘proper’, effective treatment, compared with traditional healing where therapies are provided in the absence of any diagnostic testing:

[Biomedical facilities] diagnose you and inform you of the ailment that you are suffering from, and at times inform you that your health is okay … When you visit biomedical health facilities they diagnose you and inform you of your results and in case you are HIV positive, you can start on medicine … [Traditional healers] don’t have equipment to diagnose, so how do they diagnose for conditions? … I don’t trust them. (Biomedical patient, Female)

While biomedicine is favoured for its use of diagnostic technologies, other participants describe preference for traditional healing specifically because these approaches could enable avoidance of biomedical procedures, which participants describe as ‘unnecessary’ and having high morbidity and mortality. Participants state that an advantage of traditional healing is that it supports the body to heal ‘naturally’, rather requiring modern, invasive interventions. Participants report seeking traditional care after having been told by biomedical providers that they would require an operation in order to recover. Those who ultimately healed after receiving traditional care declared that biomedical providers rush to use modern technologies, instead of allowing the body to heal on its own. One patient describes his experience receiving care from a bonesetter, after suffering severe extremity fractures after falling from a motorcycle:

[The hospital staff] told me that the doctors will cut off my leg because it was badly injured and that there was no way they could fix it … When we reached [this healer], they told me that the bone that joins the knee was broken but promised that since I was in that place, in two to three weeks, I will be able to walk again. They then aligned my leg and started the treatment … I am now getting better. If I had remained at the hospital, I know my leg would have been cut off by now. (Bonesetter patient, male)

Another patient describes how effective treatment from an herbalist allowed her sister to avoid a Caesarean section with her twin pregnancy:

These healers are very useful … my elder sister had a problem with her twin pregnancy. She was stuck with the pregnancy because the babies could not move. They took her to one of the traditional healers and was given medicine which helped her so much and she delivered her babies without difficulties. We thought she would be operated on while giving birth [via Caesarean section] because the doctors at referral hospital had told her that she will not manage to push and advised her to go for an operation, which did not happen because of the medicine the healer gave her. (Spiritual healer patient, female)

Participants described fear of using biomedical facilities to deliver their children, as they believed that physicians would perform unnecessary Caesarian sections, considered a high-risk procedure for both mothers and infants:

[Doctors] rush women to the operating theatre when it’s not necessary. Many women and babies have lost their lives due to the negligence of doctors. Women fear to deliver from hospital. (Spiritual healer patient, male)

Peer ‘testimony’ influences healthcare engagement

Our participants recount social narratives, or ‘testimonies’ which describe healthcare experiences among peers within their communities. These discursive events evaluate a provider’s competence and effectiveness in addressing ailments, and describe negative or positive outcomes of treatments. Participants indicate that peer testimonies strongly influence where they choose to seek care for their symptoms. We found that biomedical narratives frequently reinforced individual reports of mistreatment; in contrast, narratives about traditional healing were generally positive and affirmed the ‘real’ nature of this form of healthcare.

Numerous participants who received care from traditional healers describe negative peer narratives about biomedicine. A participant describes the testimony from his neighbour that influenced his decision to seek care from a traditional bonesetter:

My neighbor reached [the referral hospital after injuring his leg], but nothing much was done. They made him sit on the waiting bench and the doctor told the caretaker to go and buy a bandage and find an empty box. The doctor then dismantled the box and tied it on the leg using the bandage and left him there. He remained there until morning. …. He never got any treatment [for the leg injury] apart from the empty boxes they tied on the leg. I will never forget what he experienced from the referral hospital. It was so bad and so discouraging. Health workers do not care about patients. (Bonesetter patient, male)

A number of participants recalled community narratives indicating that healthcare workers would intentionally withhold treatment or harm their patients. One woman seeking care at a traditional birth attendant practice describes stories that made her fear that she would be harmed at the hands of healthcare workers:

There was a woman in labor who was supposed to be taken to the operating theatre but the nurses asked her for money, which she did not have. They refused to work on her until other patients contributed some money and gave it to the nurses … Those nurses do not mind whether you die from there or not … There is also one mother I heard about who took her child for immunization and got an argument with the nurse. Intentionally the nurse gave the child overdose and the child died. Some of these health workers are so wicked. (Traditional birth attendant patient, female)

Negative peer testimonies were not limited to patients of healers. For example, one woman seeking biomedical care told a story about her neighbour suffering mistreatment at the same facility.

My pregnant neighbor delivered her baby in the village compound. [When they arrived at this hospital for post-partum care], the nurse abused her, saying that she should take her stupidity back to her village. They do not care. (Biomedical patient, female).

In stark contrast to narratives surrounding biomedical care, peer testimony regarding traditional healing is largely positive. Healers are lauded for their effective care, and patients are guided by peer testimonials in selecting which healer to visit for their ailments. One participant seeking care at a traditional herbalist describes the impact of peer endorsements on her decision to seek care from this particular healer:

This healer is popular and well known, and wherever you go, people will recommend her to treat your sick child … I have seen so many different people come here to receive treatment … I am impressed. (Spiritual healer patient, male).

A central concept in many testimonies about traditional medicine is the genuineness of the healer, and how they should be set apart from traditional healers who may be ‘fake’ or ‘quacks’. One participant describes how testimonies from peers with similar injuries directed him to seek care from a specific bonesetter, and how testimonies generate more patients for particular healers:

Most traditional healers are quacks, and personally I don’t trust them.

[Interviewer: Then how do you know that you will heal from this treatment?]

I get the confidence from other people who have been treated here. There is a man from a nearby dairy. He bones were more severely broken than mine, but he healed from here, and is now doing his work. I have heard many people’s testimonies that they have been healed from here … When I come here and get healed, I will direct another one because he will be healed too and that person will also direct others… A healer who is real does not need to advertise on the radios because the people they heal create market for them. (Bonesetter patient, male)

Conceptual model

Figure 1 presents a conceptual model integrating our findings to show how influences at the healthcare provider, healthcare system and peer levels influence individual engagement with healthcare in pluralistic settings. These variables interact to shape an individual’s therapeutic itinerary, but not necessarily in a stepwise manner. For healthcare users, one or more characteristics of a healthcare system may be of paramount importance in determining use of this resource, but each modality comes with potential disadvantages. Negative experiences could prompt users to switch to the alternate modality. We heard this process described by participants who believed their ailments were initially mismanaged by biomedical providers, and were subsequently healed using traditional approaches. Similarly, positive experiences contribute towards continued use of a healthcare modality, and an individual may become reticent to engage with the alternative, in light of continued positive health outcomes.

Discussion

This study identified variables that drive engagement with healthcare resources in a medically pluralistic setting, and identified three central factors that contribute to therapeutic pluralism. These may be summarised as follows: (1) traditional healers care about their patients, while biomedical providers do not; (2) biomedical technologies can provide diagnosis and guide treatment, but these technologies are sometimes intentionally avoided; and (3) peer testimonies influence healthcare utilisation, largely in favour of traditional healing. These can be considered conceptually as factors operating at the healthcare provider, healthcare system and peer levels (figure 1).

Our work illustrates how healthcare provider characteristics are of central importance to patients. The quality of interpersonal interactions can either motivate or deter engagement with healthcare services. We found that patient–provider interactions with traditional healers are described as generally respectful and supportive, while patient–provider interactions in biomedical contexts included narratives of neglect and abuse. These findings align prior work showing that initial choice of therapeutic modality in pluralistic contexts is driven by perceived trustworthiness of a healthcare provider.18 47–50 Our participant accounts of negative interactions with biomedical staff are congruent with prior work linking negative interactions with disengagement with HIV care among PLHIV,51–53 decreased HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis utilisation among key populations54 and lack of healthcare facility use among pregnant women.55–57

We also describe how some characteristics of the available healthcare systems impact healthcare engagement. Our results speak to the hegemony of biomedicine in Uganda, and more broadly throughout postcolonial sub-Saharan Africa, where biomedicine is highly valued, and may be considered of superior quality and efficacy compared with traditional healing.58 59 Some participants report gaining reassurance through laboratory and radiological testing to guide diagnosis and therapy, describing this as “proper” treatment. We note that the desire for healthcare directed by modern test results is the central factor favouring biomedical healthcare utilisation among our participants. Interestingly, other data from high-resource contexts have shown that diagnostic test results do not increase patient reassurance or decrease health-related anxiety in outpatient biomedical settings.60 61 However, in our medically pluralistic study site, the capacity of biomedical facilities to perform diagnostic testing is distinctive in contrast to traditional medicine approaches, and therefore some patients consider access to testing as a benefit.

Traditional healthcare is sometimes preferred as a means to avoid invasive procedures, such as orthopaedic fixation, limb amputation or Caesarean section. Our findings are congruent with prior research demonstrating avoidance of facility-based obstetric services, preference for traditional home birth,30 57 62 and bonesetters to heal orthopaedic injuries in sub-Saharan Africa.32 63 Motivation to avoid invasive operative procedures is further explained by poor postoperative outcomes throughout sub-Saharan Africa.64 For example, maternal mortality after Caesarean section is 50 times higher in Africa compared with high-income countries.65 As such, patients consider invasive biomedical procedures high risk, and seek to avoid them through receipt of traditional therapies.

Additionally, we note that the content of peer testimonies strongly influences patients’ decisions to use traditional or biomedical care. Peer influences have been shown to have strong impact on individual healthcare engagement in the cases of HIV services utilisation,66–68 adolescent health,69 70 mental health71 and substance misuse,72 for example. Our study shows how peer testimonies serve as endorsements of traditional healing, legitimising its use through descriptions of clinical effectiveness. In contrast, largely negative narratives regarding biomedicine potentiate avoidance of these facilities and services.

Our findings provide insight on how patients decide to engage with particular healthcare resources, and can guide efforts to improve healthcare quality and interventions in medically pluralistic communities. Importantly, our conceptual model can direct strategies to engage those who may avoid biomedical resources, and have low uptake of conventional healthcare outreach programmes, which are frequently facility based, and/or delivered by biomedical providers. Our data suggest that healthcare users value the interpersonal interactions and trustworthiness of healers, but also may gain reassurance through receipt of biomedical testing and diagnostic technologies. An ideal health resource in a pluralistic context would potentially incorporate all of these valuable attributes. Traditional healers in Ghana have taken this approach, using components of biomedical knowledge through reference to medical textbooks and ‘Google’.73 Similarly, we know of healers in Mbarara District who use glucometers, blood pressure cuffs and performed commercially available rapid diagnostics tests for HIV and malaria. Our data suggest that decentralised healthcare services would be highly acceptable among pluralistic communities. An example of his approach at the national health policy level is demonstrated in the case of ‘differentiated care’ for PLHIV,74 where service delivery is tailored to the needs of PLHIV in their communities, and biomedical facility visits are minimised.

Finally, our data contribute to a body of work that emphasises the important role of traditional healers within the communities they serve. We hope our findings explain the persistent appeal of traditional medicine, and demonstrate that pluralistic behaviour should be considered more than ‘an inconvenient truth’ for biomedical providers, researchers and policy-makers. Low biomedical engagement in pluralistic settings should not simply be attributed to lack of access to formal resources, but should be considered an individual’s informed healthcare choice. We recommend that researchers and policy-makers involve traditional healers when designing and implementing community-based health initiatives because healers are well-positioned allies for healthcare programmes. Community members may consider healers more trustworthy than biomedical providers.50 Biomedicine could learn a great deal from healers regarding the power of interpersonal relationships as part of the healthcare process.75 76 For example, Moshabela et al77 considered the roles of traditional healers in the context of a community-wide HIV testing and treatment intervention. They found that healers boosted impact and acceptability of the intervention through educating clients on HIV-related stigma and supporting linkage to HIV care.77

Many studies have shown that healers are interested in working with biomedical providers to improve health outcomes for their patients.23 78 79 However, the converse is not typically the case. Biomedical objections to traditional healing largely focus on use of alternatively explanatory mechanisms (such as belief that evil spirits or bad luck may cause physical symptoms), lack of standardised training and oversight of practices, and delivery of varying concentrations or mixtures of herbal therapies.80 In fact, negative attitudes towards traditional medicine have been described as the primary barrier to true collaboration between traditional and biomedicine, as biomedical providers repeatedly downplay the skills and contributions of traditional healers.81 82 Biomedical providers may express distrust and disapproval of traditional medicine in interactions with their patients.81–83 Related to this lack of trust is the observation that our participant groups reported markedly different experiences with pluralistic healthcare utilisation. Most biomedical participants denied prior use of traditional medicine, while most traditional medicine users reported having previously sought biomedical care. This difference in self-reporting is likely an example of a well-described phenomenon, where patients are reticent to disclose traditional medicine use in the context of receiving biomedical care.6 83 84 Therefore, we suspect that participants seeking care in the biomedical context under-reported traditional medicine use due to fear of social judgement.

There are a few limitations of this study. We acknowledge that baseline characteristics of participants recruited from traditional healer practices are different than those recruited from an outpatient biomedical practice. Qualitative samples are intended to be relevant to the research question, and may not be representative, as would be prioritised in a quantitative study. We did not record medical histories for our participants, and cannot speak to how particular diagnoses may motivate to healthcare itinerary, beyond the symptoms prompting the current visit. This study includes only people seeking healthcare from traditional healers, and similar work is needed for those seeking care from faith healers. Further, we acknowledge the potential impact of social judgement and recognise that some biomedical participants may have been reticent to share positive feelings about traditional medicine during their interviews. Last, our qualitative data indicate multiple directions for future research. For example, what are strategies to facilitate bidirectional cooperation between traditional and biomedical systems? How would one design and implement a decentralised healthcare initiative in cooperation with traditional healers?

Conclusions

Patients perceive clear advantages and disadvantages to biomedical and traditional care in medically pluralistic settings. We identified factors at the healthcare provider, healthcare system and peer levels which can influence patients’ therapeutic itineraries, and illustrate why traditional medicine is sometimes preferred. Our findings can inform community-based, public health interventions in medically pluralistic contexts, and underscore the importance of recognising and engaging with traditional healers as important stakeholders in community health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of our research assistants, Patricia Tushemereirwe, Donny Ndazima and Doreen Nabukalu. They also appreciate the thoughtful comments provided by three manuscript reviewers. Finally, they are grateful to the traditional healers and patients in Mbarara District for sharing their experiences with them.

Footnotes

Twitter: @dr_radhikalu

Contributors: RS conceived of the study. RK and JM-A provided input on study design and study procedures. RS and JM-A oversaw data collection. RS was primarily responsible for data analysis, with input from JM-A, RK and NCW. RS composed the first draft of the manuscript. All authors provided input and approve of the final submission.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K23 MH111409), PI: Sundararajan. RK is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 MH109337). All authors are independent from the funders, and had full access to all of the data. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This research was approved by the Human Research Protections Program Institutional Research Board at the University of California, San Diego (#170672), Weill Cornell Medical College (#1803019105), Mbarara University of Science and Technology Research Ethics Committee (#16/01-17) and the Ugandan National Council for Science and Technology (#SS4338).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Deidentified data may be shared upon reasonable request by emailing the first author.

References

- 1.Shih C-C, Su Y-C, Liao C-C, et al. . Patterns of medical pluralism among adults: results from the 2001 National health interview survey in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:191. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wade C, Chao M, Kronenberg F, et al. . Medical pluralism among American women: results of a national survey. J Womens Health 2008;17:829–40. 10.1089/jwh.2007.0579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes GD, Puoane TR, Clark BL, et al. . Prevalence and predictors of traditional medicine utilization among persons living with AIDS (PLWA) on antiretroviral (ARV) and prophylaxis treatment in both rural and urban areas in South Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 2012;9:470–84. 10.4314/ajtcam.v9i4.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broom A, Wijewardena K, Sibbritt D, et al. . The use of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine in Sri Lankan cancer care: results from a survey of 500 cancer patients. Public Health 2010;124:232–7. 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014 - 2023, 20131–74 Available: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s2297e/s2297e.pdf [Accessed 30 Dec 2015].

- 6.James PB, Wardle J, Steel A, et al. . Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000895. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makundi EA, Malebo HM, Mhame P, et al. . Role of traditional healers in the management of severe malaria among children below five years of age: the case of Kilosa and Handeni districts, Tanzania. Malar J 2006;5:58. 10.1186/1475-2875-5-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saifodine A, Gudo PS, Sidat M, et al. . Patient and health system delay among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Beira City, Mozambique. BMC Public Health 2013;13:559. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beiersmann C, Sanou A, Wladarsch E, et al. . Malaria in rural Burkina Faso: local illness concepts, patterns of traditional treatment and influence on health-seeking behaviour. Malar J 2007;6:106. 10.1186/1475-2875-6-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor TN, Dolezal C, Tross S, et al. . Comparison of HIV/AIDS-specific quality of life change in Zimbabwean patients at Western medicine versus traditional African medicine care sites. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;49:552–6. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5be0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wanyama JN, Tsui S, Kwok C, et al. . Persons living with HIV infection on antiretroviral therapy also consulting traditional healers: a study in three African countries. Int J STD AIDS 2017;28:1018–27. 10.1177/0956462416685890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liwa A, Roediger R, Jaka H, et al. . Herbal and alternative medicine use in Tanzanian adults admitted with Hypertension-Related diseases: a mixed-methods study. Int J Hypertens 2017;2017:1–9. 10.1155/2017/5692572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes GD, Aboyade OM, Beauclair R, et al. . Characterizing herbal medicine use for noncommunicable diseases in urban South Africa. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015;2015:1–10. 10.1155/2015/736074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization The promotion and development of traditional medicine. Geneva: World Health Organization Technical Report Series, 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green EC, Jurg A, Dgedge A, et al. . Sexually-Transmitted diseases, AIDS and traditional healers in Mozambique. Med Anthropol 1993;15:261–81. 10.1080/01459740.1993.9966094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broom A, Doron A, Tovey P. The inequalities of medical pluralism: hierarchies of health, the politics of tradition and the economies of care in Indian oncology. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:698–706. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moshabela M, Pronyk P, Williams N, et al. . Patterns and implications of medical pluralism among HIV/AIDS patients in rural South Africa. AIDS Behav 2011;15:842–52. 10.1007/s10461-010-9747-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moshabela M, Bukenya D, Darong G, et al. . Traditional healers, faith healers and medical practitioners: the contribution of medical pluralism to bottlenecks along the cascade of care for HIV/AIDS in eastern and southern Africa. Sex Transm Infect 2017;93:e052974. 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Audet CM, Blevins M, Rosenberg C, et al. . Symptomatic HIV-positive persons in rural Mozambique who first consult a traditional healer have delays in HIV testing: a cross-sectional study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66:e80–6. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pantelic M, Cluver L, Boyes M, et al. . Medical pluralism predicts non-ART use among parents in need of art: a community survey in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Behav 2015;19:137–44. 10.1007/s10461-014-0852-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manguvo A, Mafuvadze B. The impact of traditional and religious practices on the spread of Ebola in West Africa: time for a strategic shift. Pan Afr Med J 2015;22 Suppl 1:9. 10.11694/pamj.supp.2015.22.1.6190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iskandarsyah A, de Klerk C, Suardi DR, et al. . Consulting a traditional healer and negative illness perceptions are associated with non-adherence to treatment in Indonesian women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2014;23:1118–24. 10.1002/pon.3534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King R, Homsy J. Involving traditional healers in AIDS education and counselling in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. AIDS 1997;11 Suppl A:S217–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homsy J, King R. The role of traditional healers in HIV / AIDS counselling in Kampala, Uganda. key issues and debates: traditional healers. Soc Afr SIDA 1996:2–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peltzer K, Mngqundaniso N, Petros G. A controlled study of an HIV/AIDS/STI/TB intervention with traditional healers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Behav 2006;10:683–90. 10.1007/s10461-006-9110-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Audet CM, Hamilton E, Hughart L, et al. . Engagement of traditional healers and birth attendants as a controversial proposal to extend the HIV health workforce. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2015;12:238–45. 10.1007/s11904-015-0258-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akol A, Moland KM, Babirye JN, et al. . "We are like co-wives": Traditional healers' views on collaborating with the formal Child and Adolescent Mental Health System in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:258–9. 10.1186/s12913-018-3063-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horwitz RH, Tsai AC, Maling S, et al. . No association found between traditional healer use and delayed antiretroviral initiation in rural Uganda. AIDS Behav 2013;17:260–5. 10.1007/s10461-011-0132-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sundararajan R, Mwanga-Amumpaire J, Adrama H, et al. . Sociocultural and structural factors contributing to delays in treatment for children with severe malaria: a qualitative study in southwestern Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;92:933–40. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyomuhendo GB. Low use of rural maternity services in Uganda: impact of women's status, traditional beliefs and limited resources. Reprod Health Matters 2003;11:16–26. 10.1016/S0968-8080(03)02176-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konde-Lule J, Gitta SN, Lindfors A, et al. . Private and public health care in rural areas of Uganda. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2010;10:29. 10.1186/1472-698X-10-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kisitu DK, Eyler LE, Kajja I, et al. . A pilot orthopedic trauma registry in Ugandan district hospitals. J Surg Res 2016;202:481–8. 10.1016/j.jss.2015.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ndyomugyenyi R, Neema S, Magnussen P. The use of formal and informal services for antenatal care and malaria treatment in rural Uganda. Health Policy Plan 1998;13:94–102. 10.1093/heapol/13.1.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Duijl M, Kleijn W, de Jong J. Unravelling the spirits' message: a study of help-seeking steps and explanatory models among patients suffering from spirit possession in Uganda. Int J Ment Health Syst 2014;8:24. 10.1186/1752-4458-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berger I, Buchanan C. The Cwezi cults and the history of western Uganda : Gallagher JT. Syracuse: East African Culture History, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Downs JA, Mwakisole AH, Chandika AB, et al. . Educating religious leaders to promote uptake of male circumcision in Tanzania: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2017;389:1124–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32055-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. . Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health 2015;42:533–44. 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Camlin CS, Ssemmondo E, Chamie G, et al. . Men "missing" from population-based HIV testing: insights from qualitative research. AIDS Care 2016;28 Suppl 3:67–73. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1164806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boum Y, Atwine D, Orikiriza P, et al. . Male gender is independently associated with pulmonary tuberculosis among sputum and non-sputum producers people with presumptive tuberculosis in southwestern Uganda. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:638. 10.1186/s12879-014-0638-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chikovore J, Gillespie N, McGrath N, et al. . Men, masculinity, and engagement with treatment as prevention in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care 2016;28 Suppl 3:74–82. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1178953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. SAGE Publications, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morse JM. Determining sample size. Qual Health Res 2000;10:3–5. 10.1177/104973200129118183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretive phenomenological analysis. Sage Publications, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith J, Osborn M. Interpretive phenomenological analysis In: Smith JA, ed Qualitative Psychology, 2015: 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glaser BG, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Littlewood RA, Vanable PA. A global perspective on complementary and alternative medicine use among people living with HIV/AIDS in the era of antiretroviral treatment. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2011;8:257–68. 10.1007/s11904-011-0090-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Finkler K, Healing S, Compared B. Sacred healing and biomedicine compared. Med Anthropol Q 1994;8:178–97. 10.1525/maq.1994.8.2.02a00030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sundararajan R, Kalkonde Y, Gokhale C, et al. . Barriers to malaria control among marginalized tribal communities: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2013;8:e81966. 10.1371/journal.pone.0081966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hampshire K, Hamill H, Mariwah S, et al. . The application of signalling theory to health-related trust problems: the example of herbal clinics in Ghana and Tanzania. Soc Sci Med 2017;188:109–18. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Geng EH, et al. . Toward an understanding of disengagement from HIV treatment and care in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001369. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mwamba C, Sharma A, Mukamba N, et al. . 'They care rudely!': resourcing and relational health system factors that influence retention in care for people living with HIV in Zambia. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e001007. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Layer EH, Brahmbhatt H, Beckham SW, et al. . "I pray that they accept me without scolding:" experiences with disengagement and re-engagement in HIV care and treatment services in Tanzania. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014;28:483–8. 10.1089/apc.2014.0077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J, Zarwell M, et al. . "A Gay Man and a Doctor are Just like, a Recipe for Destruction": How Racism and Homonegativity in Healthcare Settings Influence PrEP Uptake Among Young Black MSM. AIDS Behav 2019;23:1951–63. 10.1007/s10461-018-2375-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bradley S, McCourt C, Rayment J, et al. . Disrespectful intrapartum care during facility-based delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis of women's perceptions and experiences. Soc Sci Med 2016;169:157–70. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Asefa A, Bekele D, Morgan A, et al. . Service providers' experiences of disrespectful and abusive behavior towards women during facility based childbirth in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reprod Health 2018;15:4. 10.1186/s12978-017-0449-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sipsma H, Thompson J, Maurer L, et al. . Preferences for home delivery in Ethiopia: provider perspectives. Glob Public Health 2013;8:1014–26. 10.1080/17441692.2013.835434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abdullahi AA. Trends and challenges of traditional medicine in Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 2011;8:115–23. 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i5S.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Busia K. Medical provision in Africa -- past and present. Phytother Res 2005;19:919–23. 10.1002/ptr.1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rolfe A, Burton C. Reassurance after diagnostic testing with a low pretest probability of serious disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:407–16. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Ravesteijn H, van Dijk I, Darmon D, et al. . The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2012;86:3–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Geleto A, Chojenta C, Mussa A, et al. . Barriers to access and utilization of emergency obstetric care at health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa-a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 2018;7:60. 10.1186/s13643-018-0720-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Onyemaechi NO, Lasebikan OA, Elachi IC, et al. . Patronage of traditional bonesetters in Makurdi, north-central Nigeria. Patient Prefer Adherence 2015;9:275–9. 10.2147/PPA.S76877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Uribe-Leitz T, Jaramillo J, Maurer L, et al. . Variability in mortality following caesarean delivery, appendectomy, and groin hernia repair in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and analysis of published data. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e165–74. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00320-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bishop D, Dyer RA, Maswime S, et al. . Maternal and neonatal outcomes after caesarean delivery in the African surgical outcomes study: a 7-day prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e513–22. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30036-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang LW, Kagaayi J, Nakigozi G, et al. . Effect of peer health workers on AIDS care in Rakai, Uganda: a cluster-randomized trial. PLoS One 2010;5:e10923. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simoni JM, Nelson KM, Franks JC, et al. . Are peer interventions for HIV efficacious? A systematic review. AIDS Behav 2011;15:1589–95. 10.1007/s10461-011-9963-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Semitala FC, Camlin CS, Wallenta J, et al. . Understanding uptake of an intervention to accelerate antiretroviral therapy initiation in Uganda via qualitative inquiry. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20:e25033. 10.1002/jia2.25033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kågesten A, Gibbs S, Blum RW, et al. . Understanding factors that shape gender attitudes in early adolescence globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0157805. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rock A, Barrington C, Abdoulayi S, et al. . Social networks, social participation, and health among youth living in extreme poverty in rural Malawi. Soc Sci Med 2016;170:55–62. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Coatsworth-Puspoky R, Forchuk C, Ward-Griffin C. Peer support relationships: an unexplored interpersonal process in mental health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2006;13:490–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alberta AJ, Ploski RR, Carlson SL. Addressing challenges to providing peer-based recovery support. J Behav Health Serv Res 2012;39:481–91. 10.1007/s11414-012-9286-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hampshire KR, Owusu SA, Grandfathers OSA. Grandfathers, Google, and dreams: medical pluralism, globalization, and new healing encounters in Ghana. Med Anthropol 2013;32:247–65. 10.1080/01459740.2012.692740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Long L, Kuchukhidze S, Pascoe S, et al. . Differentiated models of service delivery for antiretroviral treatment of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a rapid review protocol. Syst Rev 2019;8:314–6. 10.1186/s13643-019-1210-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blasini M, Peiris N, Wright T, et al. . The role of Patient-Practitioner relationships in placebo and nocebo phenomena. Int Rev Neurobiol 2018;139:211–31. 10.1016/bs.irn.2018.07.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kleinman A, Sung LH. Why do Indigenous practitioners successfully heal? Soc Sci Med Med Anthropol 1979;13 B:7–26. 10.1016/0160-7987(79)90014-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moshabela M, Zuma T, Orne-Gliemann J, et al. . "It is better to die": experiences of traditional health practitioners within the HIV treatment as prevention trial communities in rural South Africa (ANRS 12249 TasP trial). AIDS Care 2016;28 Suppl 3:24–32. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1181296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kayombo EJ, Uiso FC, Mbwambo ZH, et al. . Experience of initiating collaboration of traditional healers in managing HIV and AIDS in Tanzania. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2007;3:6. 10.1186/1746-4269-3-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Green EC. The participation of African traditional healers in AIDS/STD prevention programmes. Trop Doct 1997;27 Suppl 1:56–9. 10.1177/00494755970270S117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.King R. Collaboration with traditional healers in HIV/AIDS prevention and care in sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review, 2000. Joint United nations program on HIV/AIDS. Available: http://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub01/jc299-tradheal_en.pdf [Accessed April 8, 2020].

- 81.Audet CM, Salato J, Blevins M, et al. . Educational intervention increased referrals to allopathic care by traditional healers in three high HIV-prevalence rural districts in Mozambique. PLoS One 2013;8:e70326–8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gall A, Anderson K, Adams J, et al. . An exploration of healthcare providers' experiences and perspectives of traditional and complementary medicine usage and disclosure by Indigenous cancer patients. BMC Complement Altern Med 2019;19:259–9. 10.1186/s12906-019-2665-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Puoane TR, Hughes GD, Uwimana J, et al. . Why HIV positive patients on antiretroviral treatment and/or cotrimoxazole prophylaxis use traditional medicine: perceptions of health workers, traditional healers and patients: a study in two provinces of South Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 2012;9:495–502. 10.4314/ajtcam.v9i4.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kelak JA, Cheah WL, Safii R. Patient's decision to disclose the use of traditional and complementary medicine to medical doctor: a descriptive phenomenology study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2018;2018:1–11. 10.1155/2018/4735234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.