To the Editor:

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) usually presents as a febrile illness with lower respiratory tract symptoms.1, 2, 3 However, atypical presentations, such as syncope, may occur. Annually in the United States, syncope triggers an estimated 1.2 million visits to emergency departments and 440,000 hospital admissions at a cost of $2.4 billion.4 Furthermore, there is wide variation among practitioners’ approaches to the evaluation of syncope, and in greater than half of the cases, the cause remains undetermined.4 The emergence of SARS-COV-2 may further complicate the evaluation of syncope. A missed or delayed diagnosis of COVID-19 because of an unusual presentation would lead to preventable exposures and increased transmission.

We sought to minimize missed or delayed diagnosis of COVID-19 by maintaining vigilance for atypical presentations of the disease.

Rochester Regional Health System is a 5-hospital health care system comprising 1,056 licensed beds, with an 11-county service area in upstate New York. For public health, infection control, and exposure determinations, the medical record of every patient who tests positive for SARS-CoV-2 by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction is prospectively reviewed. Statistical analysis was performed with ANOVA and χ2 tests.

As of March 31, 2020, of 1,950 patients tested, 163 have been confirmed as having a positive test result. After review of the first 102 consecutive patients, we observed that the main reason 24 (24%) initially sought care was syncope, near syncope, or a nonmechanical fall. Fever or the typical respiratory symptoms were secondarily or incidentally found. Compared with the group of patients who did not present with syncope, near syncope, or nonmechanical fall, a higher proportion of the syncope patients required oxygen, had gastrointestinal symptoms, or had elevated troponin levels. However, these differences were not significant (Table ). Furthermore, intravascular volume status, as reflected by mean blood urea nitrogen levels, was not significantly different (Figure ).

Table.

Characteristics of COVID-19 patients with and without syncope.

| COVID-19 Patients With Syncope, Presyncope, and Nonmechanical Falls, 24/102 (23.5%) (Mean Age 61 Years) | COVID-19 Patients Without Syncope, Presyncope, and Nonmechanical Falls, 78/102 (76.5%) (Mean Age 57 Years) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease history (%) | 7 (29) | 22 (28) | .93 |

| Required supplemental oxygen (%) | 15 (62.5) | 32 (41) | .06 |

| Reported GI symptoms (%) | 13 (54) | 28 (36) | .11 |

| Mean BUN | 20.21 | 21.29 | .76 |

| Mean troponin level | 0.40 | 0.74 | .69 |

| Patients with elevated troponin level (%) | 6 (25) | 9 (11.5) | .10 |

GI, Gastrointestinal; BUN, blood urea nitrogen.

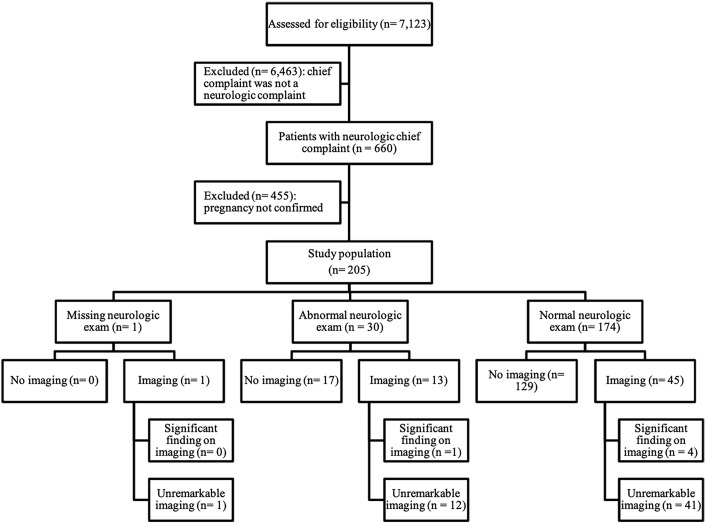

Figure.

One-way ANOVA comparing mean blood urea nitrogen values. CI, Confidence interval.

Numerous underlying conditions, both cardiogenic and noncardiogenic, can cause syncope or near syncope. Similarly, the reasons for syncope in COVID-19 patients are likely multifactorial. COVID-19 patients with underlying cardiovascular disease have increased mortality, and whether syncope is a manifestation of COVID-19–related cardiovascular disease is unknown. Cardiovascular disease is accompanied by dysregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, and SARS-Co-V2 uses the same enzyme to initiate infection.5

Studies to date have not specifically noted syncope as a presenting symptom.1, 2, 3 However, in 3 reports from China, 7.3% of COVID-19 patients complained of heart palpitations, 2% complained of chest pain, and 9.4% complained of dizziness.1, 2, 3 However, those data may not be fully generalizable to US populations because of differences in the prevalence of tobacco use and cardiovascular disease, and because of dietary patterns.

We present this to alert clinicians that syncope may be a presenting feature of COVID-19 in the United States. Vigilance for syncope as a presenting symptom can potentially allow earlier identification and isolation of infected patients.

Footnotes

Funding and support: By Annals policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist.

References

- 1.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lui K., Fang Y., Deng Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J (Engl) https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen W.K., Sheldon R.S., Benditt D.G., et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:e39–e110. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanff T.C., Harhay M.O., Brown T.S., et al. Is there an association between COVID-19 mortality and the renin-angiotensin system? a call for epidemiologic investigations. Clin Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]