Abstract

This study evaluated the feasibility and efficacy of the AgingPlus intervention program. AgingPlus is an 8-week multi-component motivational program which promotes increased physical activity by targeting adults’ negative views on aging (NVOA) and perceptions of control, two known psychological barriers to physical exercise. A total of 62 adults, ages 50–82 years, participated in this feasibility study. We assessed NVOA, perceptions of control, and physical activity level at baseline (Week 0), immediate posttest (Week 4), and delayed posttest (Week 12). High attendance rates, low attrition, and positive participant feedback indicated that the program had high acceptability. Repeated measures multivariate analyses of variance (RM-MANOVA) showed statistically significant and substantively meaningful improvements in NVOA, control beliefs, and physical activity from pretest to immediate and delayed posttest. The program effects did not differ between those younger or older than age 65. These findings provide promising support for the feasibility and efficacy of the AgingPlus program.

Keywords: intervention, views on aging, physical activity, healthy aging, control beliefs

Misperceptions about aging and older people are widely held in the general public, and are mostly negative and deterministic. Such views are in stark contrast from what is known from gerontological research and practice (Lindland, Fond, Haydon, & Kendall-Taylor, 2015). For example, aging is often thought to be synonymous with frailty, illness, and senility, and these negative outcomes are expected to be unavoidable and out of a person’s control (Ory, Hoffman, Hawkins, Sanner, & Mockenhaupt, 2003; Stewart, Chipperfield, Perry, & Weiner, 2012). Such attitudes about aging have been studied widely in the social gerontological literature and include terminology such as subjective age, age stereotypes, and expectations about aging, among others (see Diehl et al., 2014 for a review). For the present study, we use the term negative views on aging (NVOA), to refer broadly to the knowledge, beliefs, and expectations an individual holds about the process of aging and older people as a group. A large body of research shows that holding predominantly negative views on aging exerts long-term detrimental effects on adults’ health and well-being (Hummert, 2011; Levy, 2009; Westerhof et al., 2014). For instance, NVOA in midlife predict a greater risk of late-life vulnerabilities, such as falls and hospitalizations, and reduced longevity (Levy, Slade, Kunkel, & Kasl, 2002; Moser, Spagnoli, & Santos-Eggimann, 2011).

What is not yet known is whether NVOA can be altered through an intervention program, and whether doing so increases engagement in health-promoting behaviors. Therefore, we designed the AgingPlus program with a focus on changing adults’ perceptions and expectations about aging in order to motivate greater participation in physical activity. This study evaluated the feasibility and efficacy of the AgingPlus program.

The Relevance of Negative Views on Aging for Health in Adulthood

The connection between NVOA and health outcomes is unequivocal. Findings from past research consistently show that holding NVOA is associated with a host of detrimental effects, such as increased cardiovascular risk (Levy, Zonderman, Slade, & Ferrucci, 2009), lower likelihood of recovery from disability (Levy, Slade, Murphy, & Gill, 2012), and shorter life expectancy (Levy et al., 2002; Levy et al., 2016). One likely reason that NVOA influence health and functioning is that they represent a known barrier to health-promoting behaviors, including engagement in physical activity. Individuals holding NVOA in midlife are significantly less likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors as they grow older over the next 20 years (Levy & Myers, 2004) and are less likely to participate in physical activity altogether, regardless of health status (Wurm, Tomasik, & Tesch-Römer, 2010). In contrast, positive views on aging (PVOA) serve a protective role for health in middle age and later life. For example, PVOA have been shown to be associated with a higher rate of recovery from disability (Levy et al., 2012), and a longer life (Levy et al., 2002). Thus, it seems reasonable to conclude that PVOA may facilitate adults’ engagement in behaviors that promote healthy and successful aging.

Promoting Physical Activity in Later Life

One of the most effective strategies for promoting health in later life is engagement in physical activity. Contrary to beliefs held by the general public (Lindland et al., 2015), many steps can be taken to maintain healthy and independent living well into later life, including being physically active. Not only can physical activity help to prevent obesity and related chronic disease in midlife (Nejat, Polotsky, & Pal, 2010), it is also linked to preserved brain volume in later life (Tian, Studenski, Resnick, Davatzikos, & Ferrucci, 2016), stimulates neuronal regeneration in the hippocampus (Erickson et al., 2011), and reduces the risk of mobility-related disability in late life (Pahor et al., 2014). However, despite strong empirical evidence supporting the benefits of physical activity for individuals of all ages, only one in five adults meets the recommended physical activity guidelines for aerobic exercise (Healthy People 2020, 2014). Moreover, physical activity levels drop off in midlife (Schrack et al., 2014), making individuals age 50 and older the most sedentary segment of the population (Harvey, Chastin, & Skelton, 2013).

Given the pervasive evidence that most adults are not sufficiently physically active, how can engagement in physical activity be promoted? Although many attempts have been made to this effect with varying degrees of success (King, 2001; Powell, Paluch, & Blair, 2011), one approach that has so far been underutilized is to directly target the attitudes that keep people from engaging in physical exercise (King, 2001). Therefore, based on the extensive research evidence that NVOA are linked to poorer health, intervening to promote PVOA represents a promising approach to increasing physical activity.

Modifiability of Views on Aging

Although the detrimental effects of NVOA are well documented, NVOA appear to be modifiable (Kötter-Gruehn, 2015). Moreover, such a change is subsequently associated with improved behavioral performance such as improved grip strength (Stephan, Chalabaev, Kotter-Grühn, & Jaconelli, 2013), faster walking speed (Hausdorff, Levy, & Wei, 1999), improved memory (Eibach, Mock, & Courtney, 2010) and increased exercise behavior (Sarkisian, Prohaska, Davis, & Weiner, 2007; Wolff, Warner, Ziegelmann, & Wurm, 2014). Because NVOA exert a stronger effect on health than vice versa (Spuling, Miche, Wurm, & Wahl, 2013; Wurm, Tesch-Römer, & Tomasik, 2007), targeting adults’ NVOA should, therefore, result in favorable consequences for health and physical functioning. Taken together, the presented evidence provides the foundation upon which we have developed the AgingPlus program.

The AgingPlus Intervention: Theoretical Background and Curriculum

Theoretical Background.

The AgingPlus program is guided by two complementary theoretical frameworks. First, Stereotype Embodiment Theory (SEB; Levy, 2009) holds that NVOA become self-relevant in midlife, and subsequently lead to undesirable outcomes with regard to health and well-being. Therefore, AgingPlus aims to interrupt this sequence of events by teaching individuals how to recognize and counteract NVOA with the ultimate goal of preserving health and physical functioning in later life.

Second, the behavior change aspect of the AgingPlus intervention is informed by the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) model (Schwarzer et al., 2011), which integrates key elements of social cognitive theory (e.g., Bandura, 1997) to promote health behavior change. Concerned with understanding the intention-behavior gap (Schwarzer, 2008), HAPA distinguishes between the motivational phase, characterized by processes which lead to a behavioral intention, and the volitional phase, characterized by processes which ensure that the intention can be translated into actual behavior. Specific social-cognitive processes known to be important for the motivational phase include outcome and risk expectancies as well as self-efficacy (Schwarzer, 2008). The volitional phase involves known processes that individuals may employ in order to enact and maintain the desired behavior change, including self-regulatory strategies such as planning and self-monitoring (Sniehotta, Scholz, & Schwarzer, 2005).

Building upon these theoretical frameworks, the AgingPlus intervention identifies two additional processes relevant for behavior change: NVOA and control beliefs. We expect that both improved NVOA and higher control beliefs support the adoption and maintenance of physical activity as a new health behavior. Based on a solid body of social gerontological literature (e.g., Baltes & Baltes, 1986; Lachman, Neupert, & Agrigoroaei, 2011; Levy, 2009), both NVOA as well as perceived control over the environment represent barriers to physical activity in later adulthood. Furthermore, this is also consistent with social cognitive theory, as Bandura (1997) argued that behavior change is unlikely to occur unless an individual believes that he or she can enact the desired behavior, and also believes that the behaviors will in fact lead to the desired result. Therefore, the AgingPlus curriculum targets both NVOA and personal control beliefs to foster beliefs that: (1) an individual can implement a physical activity program into his or her daily life regardless of his or her chronological age; and that (2) becoming more physically active will help the individual to age in a healthier way.

Curriculum.

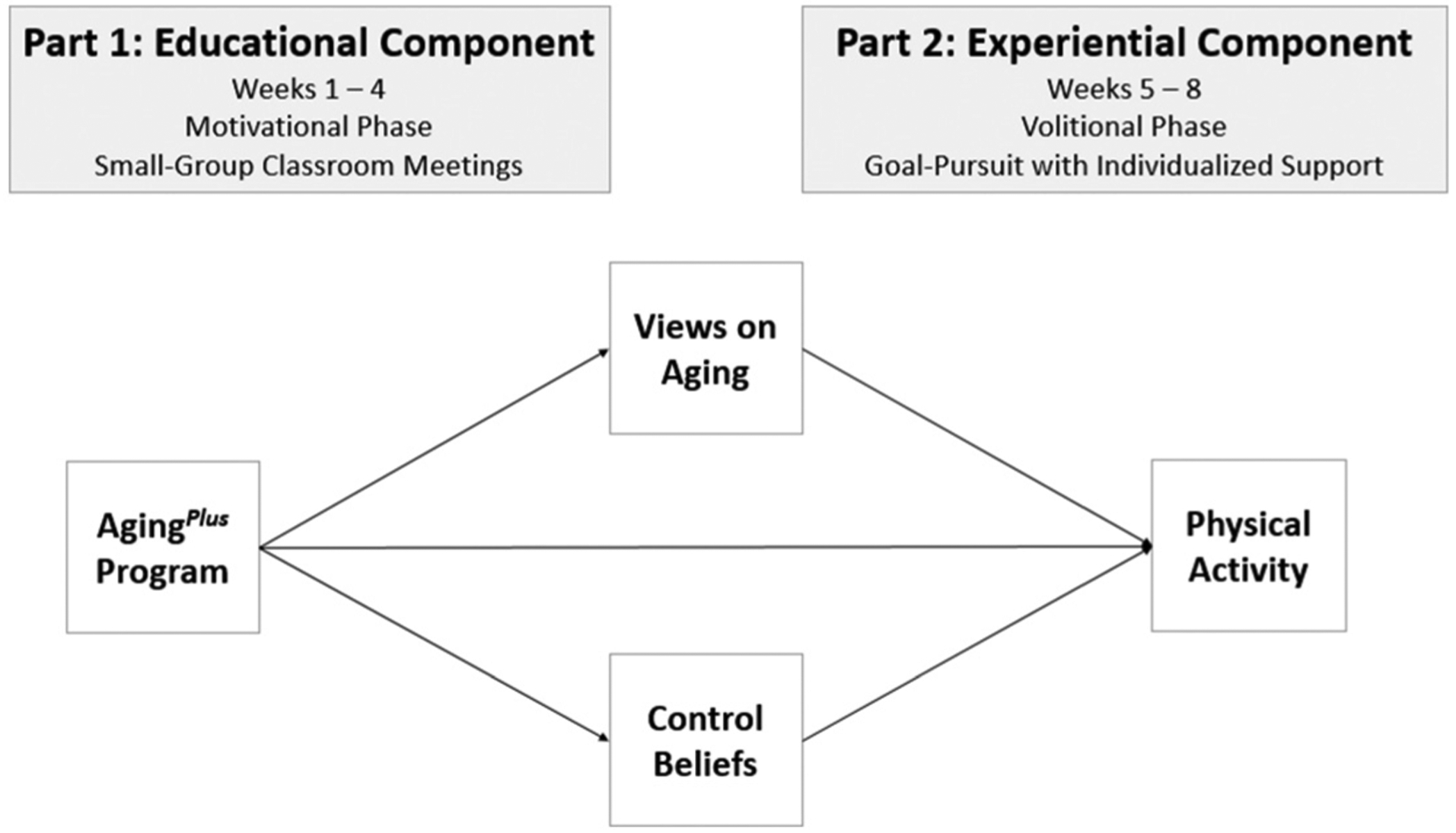

AgingPlus is a multi-component program that targets two distinct but interrelated mechanisms important for physical activity promotion: NVOA and personal control beliefs. The 8-week AgingPlus program is comprised of two components: an educational and experiential component. During the educational component (Weeks 1–4), participants attend four classroom sessions which focus on the attitudinal and motivational pieces for enacting behavior change. During the experiential component (Weeks 5–8) participants work toward their personalized physical activity goal with support from the research staff. These two components align theoretically with the HAPA model (e.g. Schwarzer, Lippke, & Luszczynska, 2011), which recognizes the importance of addressing key attitudinal processes to enact behavior change, and first-hand behavioral experiences. The conceptual model proposes NVOA and control beliefs as causal mechanisms by which the effect of the program leads to increased physical activity (Figure 1).

Figure 1 —

Conceptual model for the AgingPlus program.

Study Aims

In this study we evaluated the feasibility and efficacy of the AgingPlus program among community-residing adults and addressed three specific questions. First, we evaluated the feasibility of the program, as measured by attendance and completion rates as well as anonymous participant feedback. Second, we examined the changes in the key outcome variables throughout the program at three measurement occasions: Pretest, posttest, and delayed posttest. Specifically, we tested for change in NVOA and control beliefs, as well as in the health-promoting behavior of interest, physical activity. Third, we tested age as a moderator in order to examine whether middle-aged (< 65 years old) and older (> 65 years old) participants benefitted differentially from participating in the program.

Methods

Participants

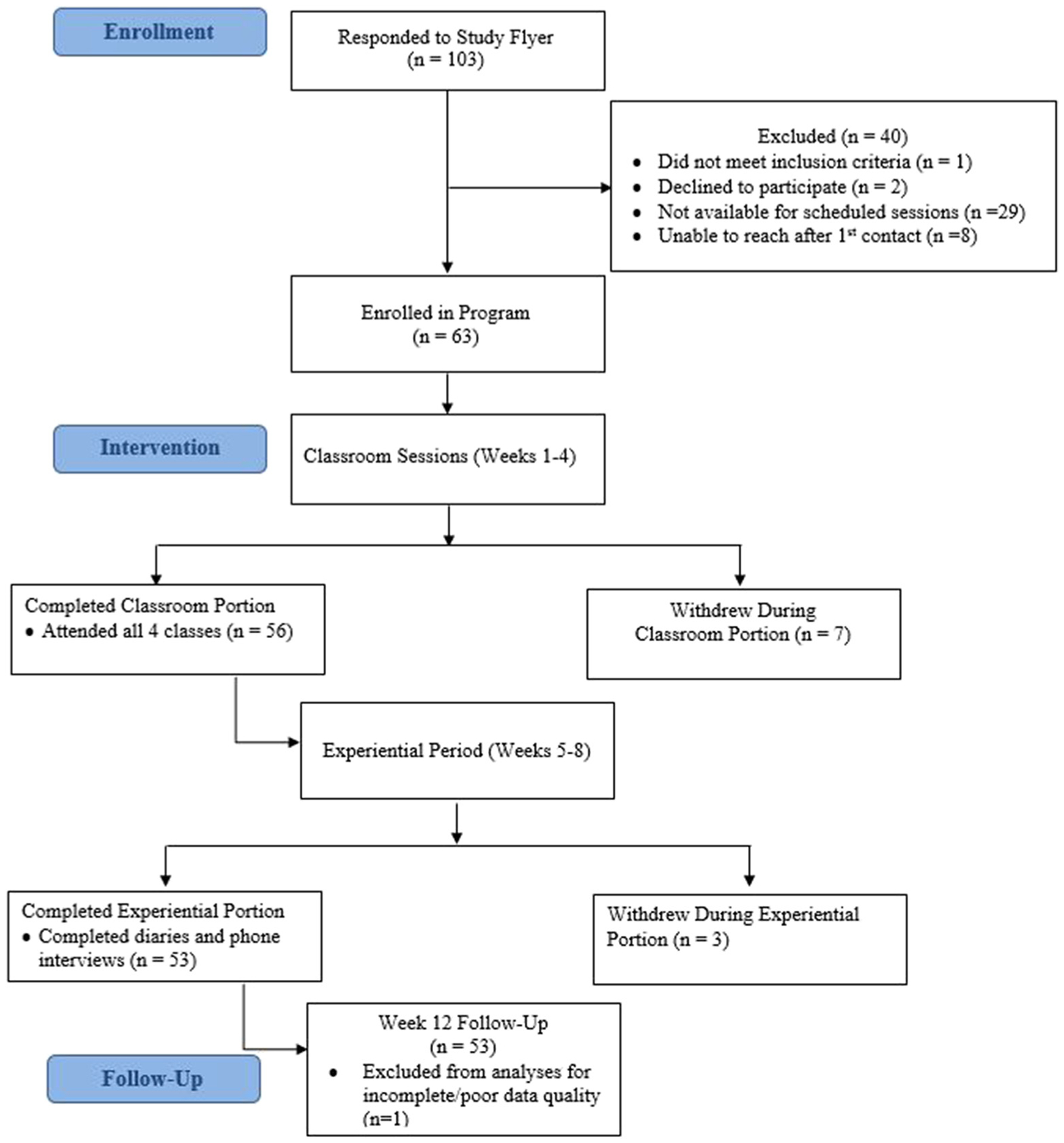

We used a single-group pretest–posttest design to assess the feasibility and efficacy of the AgingPlus program. Participants were recruited from the community via flyers and announcements circulated in partnership with local organizations. The sample was comprised of 62 community-residing adults age 50–82 years (M = 64.7 years, SD = 6.0 years; 83.9% women). Of the 62 participants, approximately half were younger than 65 (n = 32; 51.6%; range = 53.20–64.72 years), and half were age 65 or older (n = 30, 48.4%; range = 65.07–82.63 years). The majority of participants (67.7%) did not exercise regularly at baseline. Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Eligibility criteria included: (1) desire to increase current physical activity level; (2) willingness to complete the program in its entirety; and (3) English-speaking. Individuals were excluded if they reported major problems with memory that interfered with their daily activities, or if they had a severe physical condition that prevented them from being able to safely participate in physical activity of mild to moderate intensity. Participants earned up to three $20 gift certificates throughout the study as reimbursement for their time and effort. The CONSORT diagram is provided in Figure 2.

Table 1.

AgingPlus Feasibility Study Summary of Demographic Variables (N = 62)

| M (SD) or Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.26 (6.62); range: 53.2–82.6 |

| Gender | |

| Women | 52 (83.9%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 2 (3.2%) |

| Married/partnership | 35 (56.4%) |

| Separated/divorced | 19 (30.6%) |

| Widowed | 6 (9.7%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 58 (93.5%) |

| Hispanic | 3 (4.8%) |

| Other | 1 (1.6%) |

| Education (years) | 16.2 (2.45) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time | 11 (18.0%) |

| Part-time | 9 (14.8%) |

| Second career | 4 (6.5%) |

| Retired | 35 (56.5%) |

| Unemployed | 2 (3.2%) |

| Highest degree completed | |

| High school diploma/GED | 18 (29.0%) |

| Associate’s | 3 (4.8%) |

| Bachelor’s | 24 (38.7%) |

| Master’s or doctorate | 14 (22.6%) |

| Household income | |

| <$50K | 25 (40.3%) |

| $50K-100K | 19 (30.6%) |

| $100K-150K | 10 (16.2%) |

| >$150K | 4 (6.5%) |

| Self-rated health(possible range: 1 = very poor to 6 = very good) | 4.89 (.87) |

| Baseline physical activity status | |

| Thinking about it | 14 (22.6%) |

| Plan to start | 28 (45.2%) |

| Started in the past 6 months | 8 (12.9%) |

| Active for longer than 6 months | 12 (19.4%) |

Figure 2 —

Consort diagram prepared in accordance to Schulz, Altman, Moher, and CONSORT Group, (2010).

Procedures

The 12-week study period for each participant included the 8-week program plus a 1-month delayed follow-up assessment. Assessments were administered on standardized forms, and were collected at Week 0 (baseline), Week 4 (immediate posttest), and Week 12 (delayed posttest). During the educational component, participants attended four weekly meetings in small groups of 8–12 participants each. There were a total of six small groups. Classroom meetings lasted approximately 2 hr each and were taught by the same trained facilitator who was not involved in the data collection procedures. Details about the classroom curriculum are summarized in Table 2. During the experiential component, participants worked toward a self-defined physical activity goal for 4 weeks. Participants formulated their goal in terms of the number of weekly minutes of physical activity they would strive to accumulate, in accordance with the structure of the national guidelines (e.g., that 150 min of moderate physical activity are associated with substantial health benefits; Healthy People 2020, 2014). During this component, participants completed daily logs of their physical activity and also completed four weekly phone contacts with a trained research staff member. The phone contacts lasted 10–15 min, on average, and were conducted in accordance with a semi-structured interview approach using a standardized script.

Table 2.

Summary of Classroom Curriculum for the AgingPlus Program

| Primary Component | Presentation Content | Workbook & Discussion Activities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Negative Views on Aging |

|

|

| Week 2 | Negative Views on Aging; Control Beliefs |

|

|

| Week 3 | Control Beliefs (via goal planning and self-monitoring) |

|

|

| Week 4 | Control Beliefs (via goal planning and self-monitoring) |

|

|

Measures

Demographic and health characteristics.

At baseline (Week 0), an established personal data form was used to assess participants’ age, sex, education, marital status, ethnicity, employment status, and household income. Health status was assessed with a single rating of self-rated health (1 = very poor, 6 = very good).

Views on aging.

Multiple facets of NVOA were measured at Weeks 0, 4, and 12. Awareness of age-related change (AARC) assessed individuals’ positive (AARC-Gains) and negative (AARC-Losses) experiences of growing older (Diehl & Wahl, 2010). Reliability and validity have been established (Brothers, Gabrian, Diehl, & Wahl, 2016). Scale reliabilities for the present sample were acceptable at Week 0 and Week 12 (range: .67–.83), but were somewhat lower at Week 4 (.51 and .63 for gains and losses, respectively). Age stereotypes were measured with the Views of Aging scale (Kornadt & Rothermund, 2011) which assesses general opinions about “older people” in eight life domains. Cronbach’s alpha for the summary score ranged from .84 to .93. Expectations regarding aging (ERA) assessed the extent to which individuals expected to experience positive or negative age-related changes as they grow older (Sarkisian, Steers, Hays, & Mangione, 2005). Cronbach’s alpha was .88 and .91 at the two measurement occasions. Subjective age (Kastenbaum, Derbin, Sabatini, & Artt, 1972) was assessed with a 1-item measure asking how old a person tends to feel. A proportion score was calculated [(subjective age –chronological age)/chronological age] such that a negative score indicated feeling younger than one’s chronological age (e.g.,an individual scoring –.10 felt 10% younger than his or her age; Rubin & Berntsen, 2006).

Control beliefs.

We assessed both general self-efficacy and exercise-specific self-efficacy. At Weeks 0 and 12, participants’ control beliefs were assessed in terms of dispositional self-efficacy using the General Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995). This measure was not administered at Week 4 as it assesses more trait-like tendencies not expected to change after 1 month. The psychometric properties of this scale are well-established; scale reliabilities in the current study at Week 0 and 12 respectively were α = .90 and .92. The Motivational Self-Efficacy scale was used to assess domain-specific self-efficacy regarding one’s perceived ability to enact a physical activity program (Schwarzer et al., 2011). This measure was administered at Week 2 (when exercise was first discussed), Week 3 (when individuals entered the practice week of goal pursuit), and at Week 12. The motivational self-efficacy scale includes 3 items beginning with the stem “I am certain that I can be physically active on a regular basis …,” followed by statements such as, “ … when it is difficult.” Items were rated from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). The scale showed good reliability at all measurement occasions (range: α = .84–.87).

Physical activity.

Average physical activity levels were measured at Week 0 and 12 using an established self-report measure (Fleig, Lippke, Pomp, & Schwarzer, 2011), in which participants reported the number of times they engaged in mild, moderate, or vigorous physical activity per week in the last month, and the average number of minutes per session. Total weekly active minutes were calculated for Weeks 5–8 based on participants’ daily activity logs on which participants recorded the number of minutes, the type of activity, and the intensity (mild, moderate, or vigorous). The mean number of weekly minutes was calculated for Weeks 5–8.

Results

Program Feasibility

We assessed program feasibility in three ways. First, we examined attendance rates for classroom meetings. On average, the attendance rate was 93.64%, taking into consideration all four classroom meetings across all six small groups. Second, we examined the rate of attrition, which we defined as the percentage of participants who attended at least one classroom session but did not remain in the program up to the end of program at Week 8. The average attrition rate was 11.11% between Weeks 0 and 4 (n = 7), and 5.36% (n = 3) between Weeks 4 and 8. Reasons given for not returning to classes included: changed mind/program was not as expected (n = 2), scheduling conflict (n = 1), and something unexpected occurred that interfered with program attendance (n = 4). Reasons for not continuing in the daily diary portion of the study included: too busy (n = 2) and no longer interested (n = 1). One participant was lost to follow-up at Week 12. Third, we solicited structured voluntary participant feedback about the program using an online survey. The program satisfaction assessment was comprised of eight questions and included both forced response and open-ended questions. Thirty-one participants (50.0%) provided feedback, indicating a high level of satisfaction with the program. For instance, in response to the following questions, a large percentage of participants endorsed either the options “Strongly Agree” or “Agree”: The program taught me new information (100%); The program was a good use of my time (96%); and Overall the program was beneficial for me (100%).

Program Efficacy

In order to assess the efficacy of the program, we used repeated measures multivariate analyses of variance (RM-MANOVA) to examine mean differences on the key outcome variables at three measurement occasions: Pretest (Week 0), posttest (Week 4), and delayed posttest (Week 12). For general self-efficacy, which was administered only at two time points, the univariate F-test is reported. In the presence of a positive multivariate effect, pairwise comparisons were examined to determine which measurement occasions differed and in which direction.

Negative Views on Aging.

Significant multivariate effects were found for all NVOA measures, indicating an overall decrease in NVOA and a corresponding increase in PVOA throughout the program (Table 3). Specifically, participants’ perceived age-related gains increased significantly over the course of the program, F(2, 102) = 24.32, p < .001, = .32, whereas perceived age-related losses significantly decreased, F(2, 102) = 3.73, p = .03, = .07. Similarly, age stereotypes became significantly more positive, F(2, 102) = 22.70, p < .001, = .31, as did expectations regarding aging, F(2, 102) = 26.15, p < .001, = .34. Finally, participants reported a younger subjective age after taking part in the program, F(2, 102) = 5.47, p = .01, = .10. For all NVOA variables, effect sizes were in the medium ( = .06 − .14) to large ( > .14) range (Cohen, 1988). Upon examination of pairwise comparisons, there was significant improvement from Week 0 to Week 4 on AARC-Gains, Age Stereotypes, Expectations Regarding Aging, and Subjective Age (p’s < .05), but not for AARC-Losses. Similarly, pairwise comparisons showed significant improvement from Week 0 to Week 12 on all NVOA measures, including AARC-Losses (p’s < .05). However, there was a significant decline between Week 4 and Week 12 for AARC-Gains and age stereotypes (p’s < .05), suggesting a slight decay effect after the program ended.

Table 3.

Change in Mean Values of Primary Outcome Variables throughout the Study (N = 52, Unless Otherwise Specified)

| Measure | Week 0,M (SD) | Week 4,M (SD) | Week 12,M (SD) | Statistical Test (df) | Significance (p value) | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Views on aging | ||||||

| Age stereotypes | 40.85 (7.14) | 47.40 (7.64)a | 43.50 (7.30)a | F (2, 102) = 22.70 | < .001 | .31 (large) |

| AARC - Gains | 17.67 (2.83) | 20.58 (2.46)a | 19.21 (3.47)a | F (2, 102) = 24.32 | < .001 | .32 (large) |

| AARC - Losses | 11.08 (3.45) | 10.83 (2.46) | 10.02 (3.76)a | F (2, 102) = 3.73 | .028 | .07 (medium) |

| Expectations regarding aging | 50.18 (16.58) | 64.05 (16.39)a | 60.04 (18.20)a | F (2, 102) = 26.15 | < .001 | .34 (large) |

| Subjective age | −.16 (.12) | −.20 (.11)a | −.22 (.13)a | F (2, 102) = 5.47 | .01 | .10 (medium) |

| Control beliefs | ||||||

| General self-efficacy | 26.37 (4.23) | – | 28.13 (3.98)a | F (1, 51) = 14.48 | < .001 | .22 (large) |

| Motivational self-efficacy | 5.07 (.82) (Week 2) | 5.50 (.67)a (Week 3) | 5.04 (.93) | F (2, 102) = 6.89 | .002 | .22 (large) |

| Physical activity | ||||||

| Total weekly physical activity (# moderate + vigorous min) N = 50 | 84.95 (91.17) | 176.25 (89.92)a (Week 5–8 avg) | 171.55 (97.26)a | F (2, 98) 24.70 | < .001 | .34 (large) |

Abbreviations: AARC = awareness of age-related change; df = degrees of freedom.

Indicates a statistically significant improvement compared to baseline (p < .01).

Control Beliefs.

General self-efficacy, which was measured at Weeks 0 and 12, showed significant improvement after participation in the program, F(1, 51) = 14.48, p < .001, = .22. A significant multivariate effect was found for motivational self-efficacy, F(2, 102) = 6.89, p < .01, = .22, and pairwise comparisons indicated a significant improvement from Week 2 to Week 3 (p = .006). However, the Week 12 levels were not significantly different from baseline (p = .997). Means and standard deviations are displayed in Table 3.

Physical Activity.

Physical activity increased significantly throughout the program, F(2, 98) = 24.70, p < .001, = .34. As can be seen in Table 3, the average reported number of minutes spent in moderate and vigorous physical activity was significantly higher during Weeks 5–8 (M = 176.25; SD = 89.92) than at baseline (M = 84.95; SD = 91.17; p < .001). The average physical activity level remained significantly higher at Week 12 (M = 171.55; SD = 97.26; p < .001) compared to baseline. Furthermore, there was no evidence of decay between weeks 5–8 and Week 12 (p = .97). Activities reported by participants in their daily activity logs reflected a great deal of variability and individual preference. The most common activities were walking/hiking, biking, and yard-work/gardening. Other types of activities reported less commonly included going to the gym, yoga, formal exercise classes, and swimming.

Age as a Moderator of the Training Effects

In order to examine whether pretest–posttest scores differed as a function of age, we performed a series of 2 × 3 (Age Group × Time of Measurement) RM-MANOVAs. The age group interaction term was not statistically significant for any of the views on aging measures, nor for physical activity (p > .05). Therefore, middle-aged adults and older adults did not differ with regard to the pattern of change they exhibited over the course of the study. Regardless of age, participants showed a similar pattern of change by which views on aging became more positive and physical activity increased significantly after taking part in the program.

Discussion

Rapid population aging poses a number of societal challenges, such as how to motivate middle-aged (age 40–64) and older adults (age 65+) to engage in behaviors that promote healthy and successful aging (Nielsen & Reiss, 2012). Based on extensive evidence that NVOA and low control beliefs represent barriers to physical activity, we developed AgingPlus, a multi-component program that targets views on aging and control beliefs to promote engagement in physical activity in middle-aged and older adults.

The present study provides promising evidence of both the feasibility and efficacy of the AgingPlus program. With regard to the feasibility of the program, results showed that participants attended the program regularly with a fairly low drop-out rate. Furthermore, anonymous voluntary feedback was quite positive. This pattern of findings suggests that the program contains information and content that was useful to those who attended, and warrants the continued refinement and evaluation of the program. With regard to program efficacy, we found significant improvement on the key variables of interest, including views on aging, control beliefs, and physical activity at both the posttest and the delayed posttest occasions. Furthermore, effect sizes were in the medium and large ranges, signifying not only statistically significant improvements, but also substantively meaningful changes.

The results showed a consistent pattern of findings in which negative views on aging improved after participation in the program. Specifically, after the program, participants perceived more positive and less negative age-related changes; had more positive attitudes about older people in general; more positive expectations for their own aging; and even felt significantly younger than they did at the beginning of the program. That all five facets of NVOA showed statistically significant and substantively meaningful improvements throughout the program is encouraging. There have been two previous interventions that we are aware of which target views on aging as a way to increase physical activity. First, Sarkisian et al. (2007) designed an intervention in which adults living in a retirement community learned through attribution retraining that the typical decrease in physical activity that comes with age is not inevitable. Participants’ expectations regarding aging became significantly more positive, and they also walked significantly more steps per day compared to baseline. Second, Wolff et al. (2014) included a brief segment about the importance of views on aging into an existing physical activity program and were able to show that one of four assessed facets of NVOA improved. These two studies, in combination with the results from the AgingPlus program, provide encouraging support for increasing physical activity among older adults by targeting negative attitudes about aging.

Previous research has shown support for the opposite pathway as well: That interventions promoting engagement in physical activity may also be able to exert an effect on adults’ NVOA (Klusmann, Evers, Schwarzer, & Heuser, 2012). This finding suggests that the experiential period in Weeks 5–8, in which participants engage in physical activity, may contribute to a feedback loop to further promote more positive views on aging. In sum, the emergence of behavioral interventions targeting views on aging is quite promising because they represent a cost-effective avenue to promote health and functioning in later life. Behavioral interventions have the potential to prevent or even reverse mobility limitations (Pahor et al., 2014) which are directly associated with the clinical phenotype of frailty (Fried et al., 2001). Thus, preventing or delaying mobility-related disability has a great overall impact in terms of functioning and quality of life. Although NVOA interventions such as AgingPlus are in the early stages of development, they nonetheless have a solid theoretical and empirical foundation (Miche, Brothers, Diehl, & Wahl, 2015).

In addition to NVOA, we also found improvements in perceptions of both global and physical-activity-specific control beliefs, which are known to function quite differently from one another (Lachman, 1986). With regard to global control beliefs, common misperceptions of aging tend to reflect a low and decreasing sense of control: Many people believe that negative aging-related declines such as forgetfulness and frailty are unavoidable (Lindland et al., 2015). The finding that global control beliefs improved after the program is encouraging, as it suggests that the curriculum effectively empowered community-residing adults to enact change. This aim of the program to promote a greater sense of control over the aging process builds upon decades of research showing that a general sense of control over the environment is a valuable resource for adaptation, resilience and well-being in later life (Diehl & Hay, 2010; Rodin, 1986), as well as for promoting and preserving health and physical functioning (Gerstorf, Röcke, & Lachman, 2011; Lachman & Agrigoroaei, 2010).

In addition to global control beliefs, domain-specific control beliefs (e.g., motivational self-efficacy) improved during the educational component, albeit with some deterioration by the delayed posttest. An extensive body of exercise literature indicates the importance of exercise self-efficacy for initiating a physical activity program (Bandura, 1997; King, 2001). Low domain-specific control beliefs are reflected in the common attitude that one is not capable of initiating and maintaining a physical activity program. The deterioration effect suggests that a greater number of successful behavioral experiences may be necessary to enact durable improvements in domain-specific control beliefs. This finding is not entirely surprising, as unanticipated obstacles and challenges likely arose after the supportive phone calls ended. Future iterations of the program will address this issue in a systematic fashion.

From a cautionary standpoint, emphasizing the controllability of aging in an intervention for the general public must be done in a sensitive and realistic manner. The positive and empowering message that daily lifestyle habits contribute a substantial amount of the variance in later health and functioning is based on solid research evidence (e.g., Aldwin, Spiro, & Park, 2006; Ip et al., 2013) and is important information to convey. However, not all aging-related declines are preventable. Therefore, the AgingPlus curriculum tempers this message by conveying that health in later life is also shaped by environmental, social, and genetic influences which may be out of a person’s control. Nonetheless, we regard an improved general sense of control over the environment, as well as over one’s ability to become more physically active, as essential components for improving physical activity levels.

Finally, the finding that physical activity levels significantly increased throughout the study was also quite promising. Participants were largely successful in implementing their individualized physical activity plan during the experiential component and they exceeded, on average, the national guideline of 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous intensity per week. We were further encouraged to find that physical activity levels at the delayed follow-up continued to exceed the recommended levels.

There were no age-group differences between middle-aged and older adults with regard to the pattern or magnitude of change on the key outcome variables. On one hand, middle-aged adults may have been expected to benefit more from the program given that they tend to have a longer time horizon to reap the benefits from enacting positive lifestyle changes. Furthermore, midlife presents a developmentally-sensitive period because there is a heightened sense of awareness of age-related changes (Levy, 2009) and a greater likelihood of internalizing negative beliefs about aging (Eibach et al., 2010; Lachman, 2015; Levy, 2009). On the other hand, the fact that older adults benefitted equally from the program suggests that an intervention program such as AgingPlus can be advantageous at any age. This finding supports the idea of developmental plasticity and provides evidence that it is never too late to support individuals to take a more active role in promoting their own healthy aging.

This initial feasibility study has several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. First and foremost, the present study did not employ a randomized-controlled design. However, a single-group design was an important first step in the initial program evaluation. Clearly, it is not possible to know whether changes in NVOA and physical activity which occurred throughout the study period were, perhaps to some extent, attributable to other circumstances, such as the social contact received throughout the program. However, in a follow-up study with randomization, we will statistically test causal models in order to draw definitive conclusions about the program effects and path-ways specified in the conceptual model (Figure 1). Second, we had a highly motivated study sample of individuals who were already considering a behavior change. However, to put this caveat into perspective, the intentional stage of behavior change is necessary for individuals to commit to participate in a behavior change intervention (Schwarzer et al., 2011). Third, the majority of participants were women, limiting the generalizability of our findings to both sexes. In follow-up studies, we will oversample men to achieve a more balanced sex distribution. Fourth, the present study relied on self-report measures for physical activity, which are only moderately correlated with objective measures. Because experts recommend using subjective measures in conjunction with objective ones to further bolster reliability and validity (Murphy, 2009), future evaluation efforts will add an objective measure such as a triaxial pedometer or an accelerometer. Finally, the present study included uneven spacing between measurement occasions. Although uneven spacing is not ideal for general linear model approaches, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction in RM-MANOVA can test and account for any violations of the sphericity assumption (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Therefore, the use of RM-MANOVA was appropriate, especially given its statistical advantages of controlling the type I error rate.

In summary, the AgingPlus program was designed to equip middle-aged and older adults with effective ways of countering negative misperceptions of aging that would otherwise undermine their health. This feasibility study represents the first step in the development, evaluation, and refinement of the AgingPlus program. The promising findings of this study warrant continued efforts toward establishing AgingPlus as an evidence-based program.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by pilot grants from the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR025780), the Colorado School of Public Health and funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging, F31 AG051291 to Allyson Brothers and R21 AG041379 to Manfred Diehl. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Aldwin CM, Spiro A, & Park CL (2006). Health, behavior, and optimal aging: A life span developmental perspective In Birren JE, and Schaie KW (Eds.), Handbook of the Psychology of Aging (6th ed., pp. 85–104). New York, NY: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes MM, & Baltes PB (Eds.). (1986). The psychology of control and aging. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Brothers A, Gabrian M, Diehl M, Wahl H-W (2016). Measuring awareness of age-related change (AARC): a new multidimensional questionnaire to assess positive and negative subjective aging in adulthood. Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Colorado State University; Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, & Hay EL (2010). Risk and resilience factors in coping with daily stress in adulthood: the role of age, self-concept incoherence, and personal control. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1132–1146. doi: 10.1037/a0019937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, & Wahl H (2010). Awareness of age-related change: examination of a (mostly) unexplored concept. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B, 340–350. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Wahl HW, Barrett AE, Brothers AF, Miche M, Montepare JM, … Wurm S (2014). Awareness of aging: Theoretical considerations on an emerging concept. Developmental Review, 34, 93–113. doi: 10.1016/J.Dr.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eibach RP, Mock SE, & Courtney EA (2010). Having a “senior moment”: induced aging phenomenology, subjective age, and susceptibility to ageist stereotypes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 643–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, … Kramer AF (2011). Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 3017–3022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015950108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig L, Lippke S, Pomp S, & Schwarzer R (2011). Intervention effects of exercise self-regulation on physical exercise and eating fruits and vegetables: a longitudinal study in orthopedic and cardiac rehabilitation. Preventive Medicine, 53, 182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, … McBurnie MA (2001). Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Medical Sciences, 56, M146–M157. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Röcke C, & Lachman ME (2011). Antecedent-consequent relations of perceived control to health and social support: longitudinal evidence for between-domain associations across adulthood. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 61–71. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey JA, Chastin SF, & Skelton DA (2013). Prevalence of sedentary behavior in older adults: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10, 6645–6661. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10126645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausdorff JM, Levy BR, & Wei JY (1999). The power of ageism on physical function of older persons: reversibility of age-related gait changes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 47, 1346–1349. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb07437.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthy People 2020. (2014). Physical activity. Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=33

- Hummert ML (2011). Age stereotypes and aging In Schaie KW, and Willis SL (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (7th ed pp. 249–262). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ip EH, Church T, Marshall SA, Zhang Q, Marsh AP, Guralnik J, … Rejeski WJ (2013). Physical activity increases gains in and prevents loss of physical function: results from the Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders Pilot Study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 68(4), 426–432. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastenbaum R, Derbin V, Sabatini P, & Artt S (1972). The ages of me: toward personal and interpersonal definitions of functional aging. Aging and Human Development, 3, 197–211. doi: 10.2190/TUJR-WTXK-866Q-8QU7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King AC (2001). Interventions to promote physical activity by older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56, 36–46. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.suppl_2.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klusmann V, Evers A, Schwarzer R, & Heuser I (2012). Views on aging and emotional benefits of physical activity: effects of an exercise intervention in older women. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13, 236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kornadt AE, & Rothermund K (2011). Contexts of aging: assessing evaluative age stereotypes in different life domains. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 547–556. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kötter-Gruehn D (2015). Changing negative views of aging: Implications for intervention and translational research In Diehl M, and Wahl H-W (Eds.), Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics: Vol. 35. Research on Subjective Aging: New Developments and Future Directions. New York, NY: Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME (1986). Locus of control in aging research: a case for multidimensional and domain-specific assessment. Psychology and Aging, 1, 34–40. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.1.1.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME (2015). Mind the gap in the middle: a call to study midlife. Research in Human Development, 12, 327–334. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2015.1068048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, & Agrigoroaei S (2010). Promoting functional health in midlife and old age: long-term protective effects of control beliefs, social support, and physical exercise. Plos One, 5, e13297–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Neupert SD, & Agrigoroaei S (2011). The relevance of control beliefs for health and aging In Schaie KW, and Willis SL (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (7th ed, pp. 175–190). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR (2009). Stereotype embodiment: a psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB, Slade MD, Troncoso J, & Resnick SM (2016). A culture-brain link: negative age stereotypes predict alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Psychology and Aging, 31, 82–88. doi: 10.1037/pag0000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, & Myers LM (2004). Preventive health behaviors influenced by self-perceptions of aging. Preventive Medicine, 39, 625–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Slade MD, Kunkel SR, & Kasl SV (2002). Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 261–270. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Slade MD, Murphy TE, & Gill TM (2012). Association between positive age stereotypes and recovery from disability in older persons. JAMA: The Journal of The American Medical Association, 308, 1972–1973. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Zonderman AB, Slade MD, & Ferrucci L (2009). Age stereotypes held earlier in life predict cardiovascular events in later life. Psychological Science, 20, 296–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02298.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindland E, Fond M, Haydon A, & Kendall-Taylor N (2015). Gauging aging: Mapping the gaps between expert and public understandings of aging in America. Retrieved from Frame-WorksInstitute.org

- Miche M, Brothers A, Diehl M, & Wahl H-W (2015). The role of subjective aging within the changing ecologies of aging In Diehl M, and Wahl HW (Eds.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics: Research on Subjective Aging: New Developments and Future Directions (Vol. 35, pp. 211–245). New York, NY: Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Moser C, Spagnoli J, & Santos-Eggimann B (2011). Self-perception of aging and vulnerability to adverse outcomes at the age of 65–70 years. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66B, 675–680. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SL (2009). Review of physical activity measurement using accelerometers in older adults: considerations for research design and conduct. Preventive Medicine, 48, 108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejat EJ, Polotsky AJ, & Pal L (2010). Predictors of chronic disease at midlife and beyond: the health risks of obesity. Maturitas, 65, 106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen L, & Reiss D (2012). Motivation and aging: Toward the next generation of behavioral interventions. (Background Paper: NIA-BBCSS Expert Meeting). Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Ory M, Hoffman MK, Hawkins M, Sanner B, & Mockenhaupt R (2003). Challenging aging stereotypes: strategies for creating a more active society. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25, 164–171. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00181-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ambrosius WT, Blair S, Bonds DE, Church TS, … LIFE Study Investigators. (2014). Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults The LIFE study randomized clinical trial. JAMA: The Journal Of The American Medical Association, 311, 2387–2396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KE, Paluch AE, & Blair SN (2011). Physical activity for health: What kind? How much? How intense? On top of what? Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 349–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J (1986). Aging and health: effects of the sense of control. Science, 233, 1271–1276. doi: 10.1126/science.3749877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, & Berntsen D (2006). People over forty feel 20% younger than their age: subjective age across the lifespan. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 13, 776–780. doi: 10.3758/BF03193996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian CA, Prohaska TR, Davis C, & Weiner B (2007). Pilot test of an attribution retraining intervention to raise walking levels in sedentary older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55, 1842–1846. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian CA, Steers WN, Hays RD, & Mangione CM (2005). Development of the 12-item expectations regarding aging survey. The Gerontologist, 45, 240–248. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrack JA, Zipunnikov V, Goldsmith J, Bai J, Simonsick EM, Crainiceanu C, & Ferrucci L (2014). Assessing the “physical cliff”: detailed quantification of age-related differences in daily patterns of physical activity. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 69, 973–979. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, & CONSORT Group. (2010). CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63, 834–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, (2008). Models of health behaviour change: Intention as mediator or stage as moderator? Psychology & Health, 23(3), 259–262. doi: 10.1080/08870440801889476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, & Jerusalem M (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale In Weinman J, Wright S, & Johnston M (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Lippke S, & Luszczynska A (2011). Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA). Rehabilitation Psychology, 56(3), 161–170. doi: 10.1037/a0024509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sniehotta FF, Scholz U, & Schwarzer R (2005). Bridging the intention-behaviour gap: planning, self-efficacy, and action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical exercise. Psychology and Health, 20, 143–160. doi: 10.1080/08870440512331317670 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spuling SM, Miche M, Wurm S, & Wahl H-W (2013). Exploring the causal interplay of subjective age and health dimensions in the second half of life: a cross-lagged panel analysis. Zeitschrift Fur Gesund-heitspsychologie, 21, 5–15. doi: 10.1026/0943-8149/a000084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan Y, Chalabaev A, Kotter-Grühn D, & Jaconelli A (2013). “Feeling younger, being stronger”: an experimental study of subjective age and physical functioning among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68, 1–7. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart TL, Chipperfield JG, Perry RP, & Weiner B (2012). Attributing illness to ‘old age:’ consequences of a self-directed stereotype for health and mortality. Psychology and Health, 27(8), 881–897. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.630735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS (2007). Multivariate analysis of variance and covariance (5th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Tian Q, Studenski SA, Resnick SM, Davatzikos C, & Ferrucci L (2016). Midlife and late-life cardiorespiratory fitness and brain volume changes in late adulthood: results from the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 71, 124–130. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof GJ, Miche M, Brothers AF, Barrett AE, Diehl M, Montepare JM, … Wurm S (2014). The influence of subjective aging on health and longevity: a meta-analysis of longitudinal data. Psychology and Aging, 29, 793–802. doi: 10.1037/a0038016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JK, Warner LM, Ziegelmann JP, & Wurm S (2014). What do targeting positive views on ageing add to a physical activity intervention in older adults? Results from a randomised controlled trial. Psychology and Health, 29, 915–932. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.896464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurm S, Tesch-Römer C, & Tomasik MJ (2007). Longitudinal findings on aging-related cognitions, control beliefs, and health in later life. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, P156–P164. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.3.P156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurm S, Tomasik MJ, & Tesch-Römer C (2010). On the importance of a positive view on ageing for physical exercise among middle-aged and older adults: cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Psychology and Health, 25, 25–42. doi: 10.1080/08870440802311314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]