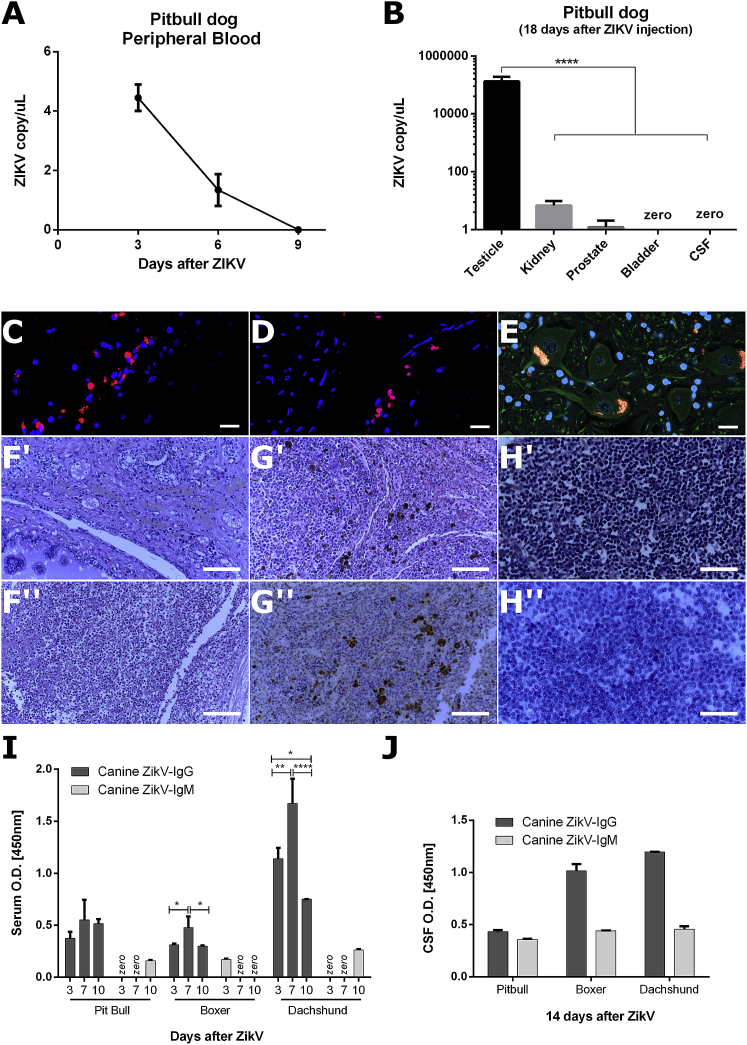

Figure 1.

Safety of ZIKVBR Intrathecal Injection in Dogs

(A) Viral RNA copies of peripheral blood serum at 3, 6, and 9 days after ZIKVBR intrathecal injection in Pitbull immunosuppressed dog. (B) Viral titer in testicle, kidney, prostate bladder, and CSF samples at euthanasia in Pitbull dog, 18 days after ZIKVBR injection (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). (C and D) Representative images of frontal lobe (C) and medulla (D) CNS tissues IF immunolabeling for ZIKVBR (red), and nuclei DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm. (E) Representative images of neurons from CNS tissues IF immunolabeling for ZIKVBR (red), β3-tubulin cytoplasmatic (green) protein, and nuclei DAPI (blue). Yellow staining in neuron image (E) shows unspecific staining for lipofuscin accumulation. Scale bar, 20 μm. (F) H&E representative images of urologic tissues: prostate (Fʹ) and testicle (Fʹʹ). Scale bar, 100 μm. (G) Representative spleen tissue of H&E (Gʹ) and IHC immunolabeling for ZIKVBR (brown) and hematoxylin (blue) (Gʹʹ). Scale bar, 100 μm. (H) Representative lymph node tissue of H&E (Hʹ) and IHC immunolabeling for ZIKVBR (brown) and hematoxylin (blue) (Hʹʹ). Scale bar, 500 μm. The brown areas in H&E preparation of spleen (Gʹ) and lymph node tissue (Hʹ) suggests a hemosiderin accumulation. Canine ZIKV-IgG and ZIKV-IgM quantification by ELISA in peripheral blood serum (I) and CSF (J) dog samples. (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Three technical replicas for each sample).