Abstract

Background & Aims

Multiple gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, and abdominal pain, as well as liver enzyme abnormalities, have been variably reported in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This document provides best practice statements and recommendations for consultative management based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of international data on GI and liver manifestations of COVID-19.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature search to identify published and unpublished studies using OVID Medline and preprint servers (medRxiv, LitCovid, and SSRN) up until April 5, 2020; major journal sites were monitored for US publications until April 19, 2020. We pooled the prevalence of diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, as well as liver function tests abnormalities, using a fixed-effect model and assessed the certainty of evidence using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) framework.

Results

We identified 118 studies and used a hierarchal study selection process to identify unique cohorts. We performed a meta-analysis of 47 studies including 10,890 unique patients. Pooled prevalence estimates of GI symptoms were as follows: diarrhea 7.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.2%–8.2%), nausea/vomiting 7.8% (95% CI, 7.1%–8.5%), and abdominal pain 2.7% (95% CI, 2.0%–3.4%). Most studies reported on hospitalized patients. The pooled prevalence estimates of elevated liver abnormalities were as follows: aspartate transaminase 15.0% (95% CI, 13.6%–16.5%) and alanine transaminase 15.0% (95% CI, 13.6%–16.4%). When we compared studies from China to studies from other countries in subgroup analyses, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, and liver abnormalities were more prevalent outside of China, with diarrhea reported in 18.3% (95% CI, 16.6%–20.1%). Isolated GI symptoms were reported rarely. We also summarized the Gl and liver adverse effects of the most commonly utilized medications for COVID-19.

Conclusions

GI symptoms are associated with COVID-19 in <10% of patients. In studies outside of China, estimates are higher. Further studies are needed with standardized GI symptoms questionnaires and liver function test checks on admission to better quantify and qualify the association of these symptoms with COVID-19. Based on findings from our meta-analysis, we provide several Best Practice Statements for the consultative management of COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Gastrointestinal and Liver Manifestations

Abbreviations used in this paper: AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; GI, gastrointestinal; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LFT, liver function test; MERS, Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RT-PCR, real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; ULN, upper limit of normal

The coronavirus family has 4 common human coronaviruses (ie, 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1) associated with the common cold, and 3 strains that are associated with pneumonia, respiratory failure, and death, including SARS-CoV (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus), MERS-CoV (Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus), and SARS-CoV-2.1 The novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, was first described in December 2019 in patients in Wuhan, China who developed severe pneumonia, and was named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization on February 11, 2020.2 COVID-19 is estimated to have resulted in 2,896,633 cases in 185 countries with 202,832 deaths as of April 25, 2020.3 COVID-19 was first reported in the United States on January 20, 2020 and accounted for a total number of 938,154 cases and 53,755 deaths as of April 25, 2020. In the United States, an early analysis of the first 4226 cases from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as of March 16, 2020 revealed estimated rates of hospitalization of 20.7%–31.4%; intensive care unit admission of 4.9%–11.5%; and case fatality of 1.8%–3.4%.4 More recent data from a cohort of 5700 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 within a large health care system in New York City revealed common comorbidities, including hypertension (56.6%), obesity (41.7%), and diabetes (33.8%), and reported that 373 patients (14.2%) required treatment in the intensive care unit, and 320 patients (12.2%) received invasive mechanical ventilation, in whom the mortality rate was 88.1% (282 of 320)].5

Angiotensin converting enzyme II, believed to be the target entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2, is abundantly expressed in gastric, duodenal, and rectal epithelia, thereby implicating angiotensin converting enzyme II as a vehicle for possible fecal–oral transmission.6 In addition, angiotensin converting enzyme II receptors can be expressed in hepatic cholangiocytes7 and hepatocytes,8 potentially permitting direct infection of hepatic cells.

Nongastrointestinal symptoms for COVID-19 include fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, repeated shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, and new loss of taste or smell. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and/or diarrhea have been reported in patients with COVID-19. Additionally, abnormal liver enzymes are also observed.9 However, significant heterogeneity has been observed in the reporting of GI and liver symptoms across settings.10 The most commonly reported GI symptom in COVID-19 is diarrhea, which has been reported in 1%–36% of patients.10 An updated characterization of the GI and liver manifestations across global settings is needed to further inform clinical guidance in the management of patients with COVID-19.

Scope and Purpose

We seek to summarize international data on the Gl and liver manifestations of COVID-19 infection and treatment. Additionally, this document provides evidence-based clinical guidance on clinical questions that gastroenterologists may be consulted for. This rapid review document was commissioned and approved by the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee, AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee, and the AGA Governing Board to provide timely, methodologically rigorous guidance on a topic of high clinical importance to the AGA members and the public. Table 1 provides a summary of the recommendations and best practice statements.

Table 1.

Summary of Best Practice Statements: Consultative Management of Coronavirus Disease 2019

| Statement no. | Statement |

|---|---|

| 1 | In outpatients with new-onset diarrhea, ascertain information about high-risk contact exposure; obtain a detailed history of symptoms associated with COVID-19, including fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, or new loss of taste or smell; and obtain a thorough history for other Gl symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. |

| 2 | In outpatients with new-onset Gl symptoms (eg, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea), monitor for symptoms associated with COVID-19, as GI symptoms may precede COVID-related symptoms by a few days. In a high COVID-19 prevalence setting, COVID-19 testing should be considered. |

| 3 | In hospitalized patients with suspected or known COVID-19, obtain a thorough history of GI symptoms (ie, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea), including onset, characteristics, duration, and severity. |

| 4 | There is presently inadequate evidence to support stool testing for diagnosis or monitoring of COVID-19 as part of routine clinical practice. |

| 5 | In patients (outpatients or inpatients) with elevated LFTs in context of suspected or known COVID-19, evaluate for alternative etiologies. |

| 6 | In hospitalized patients with suspected or known COVID-19, obtain baseline LFTs at the time of admission and consider LFT monitoring throughout the hospitalization, particularly in the context of drug treatment for COVID-19 |

| 7 | In hospitalized patients undergoing drug treatment for COVID-19, evaluate for treatment-related Gl and hepatic adverse effects. |

Panel Composition and Conflict of Interest Management

This rapid review and guideline was developed by gastroenterologists and guideline methodologists from the 2 AGA committees. The guideline panel worked collaboratively with the AGA Governing Board to develop the clinical questions, review the evidence profiles, and develop the recommendations. Panel members disclosed all potential conflicts of interest according to AGA Institute policy.

Target Audience

The target audience of this guideline includes gastroenterologists, advanced practice providers, nurses, and other health care professionals. Patients as well as policy-makers can benefit from these guidelines. These guidelines are not intended to impose a standard of care for individual institutions, health care systems, or countries. They provide the basis for rational informed decisions for clinicians, patients, and other health care professionals in the setting of a pandemic.

Methods

Information Sources and Literature Search

We conducted a systematic literature search to identify all published and unpublished studies that could be considered eligible for our review, with no restrictions on languages. In the setting of a pandemic with exponential increases in published and unpublished studies, our search strategy was multifaceted. To capture relevant published articles, we electronically searched OVID Medline from inception to March 23, 2020 using the Medical Subject Heading term developed for COVID-19. We then searched the following platforms on April 5, 2020 for additional published and unpublished studies: medRxiv, LitCovid,11 and SSRN. An additional unpublished article under peer review was obtained through personal communication. For studies from the United States, we continued to monitor major journals for additional publications until April 19, 2020.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Independent screening of titles and abstracts was performed by independent reviewers (P.D., S.S., J.F.) to identify potential studies for inclusion. A second reviewer (O.A.) subsequently reviewed the full-text articles and identified articles for inclusion. Any disagreements about inclusion were resolved through discussion. We incorporated any studies (prospective or retrospective) that reported on patient characteristics and symptoms of interest. For studies published in Chinese, we used Google translate to assess for potential inclusion and for data extraction.

Due to concerns about inclusion of the same patients in different publications, we used a hierarchical model of data extraction to minimize double counting of patients across similar institutions with coinciding dates of study inclusion. We aimed to identify and include data from the largest possible cohort from each location or hospital.12 Data extraction was performed using a 2-step process. The initial data extraction focused on data elements for study and patient characteristics. Subsequently, we identified studies for full data extraction based on study location (unique hospitals) and total number of patients. Additionally, when a study from a specific hospital did not provide all of the necessary information for the diarrhea symptoms, the next largest study from the same hospital (when available) was selected for inclusion in our analysis.

Data extraction was performed using a standardized Microsoft Excel data extraction form. Data extraction was performed in pairs; one study author independently extracted data while a second reviewer checked for accuracy of the data extraction (S.S., O.A., S.M.S., P.D., J.D.F., J.K.L., Y.F.Y., H.B.E.). Because the reporting of the data in the primary studies was suboptimal, a third reviewer (O.A.) additionally verified the extracted data to confirm the numbers and to resolve any disagreements. Studies with discrepancies in the data were excluded.

The following data elements were extracted:

-

1.

Study: author, year, location (hospital name, city, province or state), dates of inclusion, and date of last follow-up

-

2.

Patient characteristics: number of patients, age (mean, median, interquartile interval or range), number of females, severity of illness, inclusion criteria (hospitalized or outpatients), GI comorbidities (pre-existing conditions, such as chronic liver disease, hepatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease)

-

3.

Outcomes: diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and liver function test (LFT) abnormalities

-

4.

Additional information: severity, characteristics, duration, timing (before or concurrent with respiratory symptoms), relationship with clinical outcomes (need for ventilator, survival, discharge, and continued hospitalization), and viral stool shedding.

Assessment of Risk of Bias

We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains as suggested in the ROBINS-I tool for nonrandomized studies.13

-

1.

Bias due to selection of participants in the study

-

2.

Bias due to missing data

-

3.

Bias in the measurement of outcomes

-

4.

Bias in the selection of the reported result

We considered the domains for each study and then made a judgment of high or low risk of bias for the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Certainty of Evidence

Certainty of evidence was evaluated using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) framework. The certainty of evidence was categorized into 4 levels ranging from very low to high. Within the GRADE framework, evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) starts as high-certainty evidence and observational studies start out as low-certainty evidence, but can be rated down for the following reasons: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. Additionally, evidence from well-conducted observational studies start as low-certainty evidence, but can be rated up for large effects or dose–response.14

Data Synthesis and Analysis

A meta-analysis of prevalence of GI and liver abnormalities was performed using meta 4.11-0 package in R software, version 3.6.3.15 , 16 The prevalence was expressed as a proportion and 95% confidence interval (CI). We used the fixed-effects model using the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation method for proportions. This is the preferred method of transformation and avoids giving an undue larger weight to studies with very large or very small prevalence.17 , 18 The I 2 statistic was used to measure heterogeneity.19 To explore heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses based on the location (region) of the study and clinical settings (inpatient vs outpatient). To assess the robustness of our results, we performed sensitivity analyses by limiting the included studies to those that clearly reported the presence of symptoms at initial presentation.

Results

A total of 57 studies were ultimately selected for complete data extraction; 56 from our search and 1 additional manuscript (under review) was included to provide more data on a US cohort20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76 (see Supplementary Figure 1 for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram). Of the 57 selected studies, 47 reported on unique patients based on hospital name (with no duplication of cohorts from the same hospital). An additional 10 studies were identified with potentially overlapping cohorts based on hospital name, but these were included if they provided unique information about a specific symptom (eg, diarrhea at initial presentation when the larger cohort did not clearly state that it was at initial presentation). Based on our comprehensive selection process, we believe that the included 47 studies reported data on 10,890 unique COVID-19 patients. The majority of studies (70%) in our analysis were from China; these were selected from 118 reports published or prepublished from China (Supplementary Figure 2). The studies included mainly adults, although a few studies included a small proportion of pediatric patients. Two studies reported on outpatients only, whereas the remaining 55 studies reported on hospitalized patients or a combination of outpatients and hospitalized patients. Based on our inclusion strategy: 55 studies (96%) provided information on any GI symptom and 32 studies (56%) reported any data on liver abnormalities. Fewer studies, 21 (37%), provided information on underlying GI conditions. Table 2 provides a summary of the pooled prevalence estimates.

Supplement Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram

Supplementary Figure 2.

The matrix used in the selection of the Chinese studies. The X-axis represents the studies. The Y axis represent the hospitals included in the study. The size of the bubble reflects the number of patients in the study. Two studies by Guan et al101,102 were not included in the plot as they included patients from more than 500 hospitals from 30 or more provinces without providing the names of the hospitals.

Table 2.

Summary of the Pooled Prevalence Estimates of Gastrointestinal/Liver Manifestations

| GI and liver manifestations | All studies |

Studies from China |

Studies from countries other than China |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | Patients/ studies, n | % (95% CI) | Patients/ studies, n | % (95% CI) | Patients/ studies, n | |

| Diarrhea in all patientsa | 7.7 (7.2 to 8.2) | 43/10,676 | 5.8 (5.3 to 6.4) | 32/8612 | 18.3 (16.6 to 20.1) | 11/2064 |

| Nausea/vomiting in all patientsa | 7.8 (7.1 to 8.5) | 26/5955 | 5.2 (4.4 to 5.9) | 19/4054 | 14.9 (13.3 to –16.6) | 7/1901 |

| Abdominal pain in all patientsa | 3.6 (3.0 to 4.3) | 15/4031 | 2.7 (2.0 to 3.4) | 10/2447 | 5.3 (4.2 to 6.6) | 5/1584 |

| Patients with elevated AST | 15.0 (13.6 to 16.5) | 16/2514 | 14.9 (13.5 to 16.4) | 14/2398 | 20.0 (12.8 to 28.1) | 2/116 |

| Patients with elevated ALT | 15.0 (13.6 to 16.4) | 17/2711 | 14.9 (13.5 to 16.3) | 15/2595 | 19.0 (12.0 to 27.1) | 2/116 |

| Patients with elevated total bilirubin | 16.7 (15.0 to 18.5) | 10/1841 | 16.7 (15.0 to 18.5) | 10/1841 | — | — |

Regardless of hospitalization and timing of symptoms.

Overall Certainty of Evidence

The overall certainty in the body of evidence was low. Our confidence in the pooled estimates of prevalence was reduced because of concerns of risk of bias (ie, selection bias, detection bias, and attrition bias), heterogeneity of the tested patient populations (inconsistency), as well as issues of indirectness (the majority of studies included primarily symptomatic hospitalized patients instead of all patients with COVID-19). Additionally, most of the studies were retrospective cohort series and did not specify whether consecutive patients were included in the analysis. Other limitations included inconsistent assessment of symptoms and/or laboratory tests, missing data and/or inconsistent reporting of data, and insufficient follow-up of the patients. These factors may have contributed to the heterogeneity of findings across studies. The I 2 statistic ranged from 77% to 98% and was not completely explained by geographic location or by outpatient vs inpatient status.

What are the Gastrointestinal Manifestations of COVID-19?

Diarrhea

A total of 43 studies including 10,676 COVID-19 patients (confirmed by laboratory real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR] testing) were included in the overall analysis.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 , 37 , 38 , 41 , 42 , 45 , 47 , 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 , 58 , 59 , 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71 , 73 , 76 The pooled prevalence of diarrhea symptoms across these studies was 7.7% (95% CI, 7.2%–8.2%). When analyzing by country (studies from China vs studies from other countries), the pooled prevalence of diarrhea in studies from countries other than China was much higher at 18.3% (95% CI, 16.6%–20.1%). This is in comparison to studies from China, where the prevalence was much lower at 5.8% (95% CI, 5.3%–6.4%) (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of the prevalence of diarrhea in all patients.

In hospitalized patients, across 39 studies including 8,521 patients, the pooled prevalence was slightly higher at 10.4% (95% CI, 9.4%–10.7%) compared with outpatients.20, 21, 22, 23 , 25, 26, 27, 28 , 30 , 33, 34, 35 , 38 , 41 , 42 , 44, 45, 46 , 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 , 60 , 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68 , 70, 71, 72, 73, 74 , 76 In 3 studies including 1701 outpatients, the pooled prevalence was 4.0% (95% CI, 3.1%–5.1%).31 , 59 , 63 As part of the sensitivity analysis, we identified 35 studies including 9717 patients that described diarrhea, and explicitly reported that it was one of the initial presenting symptoms.20, 21, 22, 23 , 26, 27, 28 , 31 , 33, 34, 35 , 38 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 , 60 , 63, 64, 65, 66 , 68, 69, 70, 71 , 74 , 76 The pooled prevalence in these studies was 7.9% (95% CI, 7.4%–8.6%). A total of 33 studies including 8070 patients reported on hospitalized COVID-19 patients presenting with diarrhea as one of the initial symptoms of COVID-19.20, 21, 22, 23 , 26, 27, 28 , 33, 34, 35 , 38 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 45 , 48 , 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 , 60 , 63, 64, 65, 66 , 68 , 70, 71, 72, 73 , 76 The pooled prevalence was 9.3% (95% CI, 8.6%–9.9%) (Supplementary Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 4, Supplementary Figure 5, Supplementary Figure 6).

Supplementary Figure 3.

Forest plot of the prevalence of diarrhea in all admitted patients regardless of the timing of diarrhea.

Supplementary Figure 4.

Forest plot of the prevalence of diarrhea as one of the initial symptoms in all patients regardless of hospitalization status.

Supplementary Figure 5.

Forest plot of the prevalence of diarrhea as one of the initial symptoms in all admitted patients.

Supplementary Figure 6.

Forest plot of the prevalence of diarrhea in outpatients regardless of the timing of diarrhea.

Description of diarrhea

Only a handful of studies provided any details on the type and severity of diarrhea symptoms.55 , 60 , 74 In the study by Lin et al,55 23 of 95 patients (24%) reported having diarrhea (described as loose or watery stools, ranging from 2–10 bowel movements per day); however, only a small number of patients actually had diarrhea on admission (5.2%). Most patients developed diarrhea during the hospitalization, which may have been attributable to other treatments or medications. In the study by Jin et al60 of 651 hospitalized patients, 8.6% of patients had diarrhea on admission before receiving any treatments. The diarrhea symptoms were described as more than 3 loose stools per day. Stool cultures were negative (including Clostridium difficile) in all patients. There was no mention of fecal leukocytes. Median duration of symptoms was 4 days (range, 1–9 days) and most patients had self-limited diarrheal symptoms.60 One additional study on 175 hospitalized patients reported that 19.4% of patients had diarrhea, with an average of 6 episodes per day, with symptom duration ranging from 1 to 4 days.74

Diarrhea as the only presenting symptom in the absence of upper respiratory symptoms

In the 43 studies that informed our analysis on the prevalence of diarrhea, we extracted information on whether diarrhea was reported as the only presenting symptom.50 , 60 In only 2 studies, there was explicit reporting of diarrhea in the absence of upper respiratory infection symptoms. In a study by Luo et al50 of 1141 patients, 183 patients (16%) presented with GI symptoms only in the absence of respiratory symptoms. Of 1141 patients, loss of appetite (15.8%) and nausea or vomiting (11.7%) were the most common symptoms, but diarrhea was reported in 6.0% and abdominal pain in 3.9% of patients. Notably, the majority of patients (96%) had lung infiltrates on chest computed tomography. In the study by Jin et al60 of 651 hospitalized patients, 21 patients (3.2%) presented with GI symptoms only (and no respiratory symptoms of coughing or sputum production).60 GI symptoms were defined as at least 1 of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Conversely, in the US study of 116 patients with COVID-19, Cholankeril et al70 reported that 31.9% of patients had GI symptoms on admission (median duration, 1 day); diarrhea was reported in 10.3% (12 of 116), nausea and/or vomiting in 10.3% (12 of 116), and abdominal pain in 8.8% (10 of 116). The authors explicitly reported that none of the 116 patients had isolated GI symptoms as the only manifestation of COVID-19.

Diarrhea as the initial presenting symptom preceding other COVID-19 symptoms

Of the studies included in our review, based on our selection framework, we identified only 1 study that reported on timing of diarrhea in relation to other COVID-19–related symptoms. In a study by Ai et al76 of 102 hospitalized patients, 15 patients reported diarrhea symptoms on hospital admission, and diarrhea was the first symptom in 2 patients. In a study by Wang et al77 of 138 consecutive hospitalized patients, not included in our pooled analysis, a total of 14 patients presented with diarrhea and nausea 1–2 days before the development of fever and dyspnea.

Nausea/vomiting

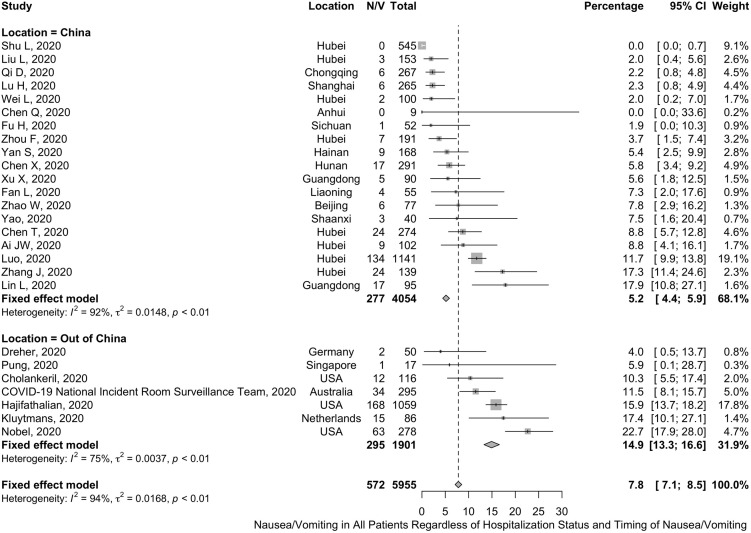

A total of 26 studies including 5955 patients with COVID-19 (confirmed by laboratory RT-PCR testing), were included in the overall analysis for nausea and/or vomiting.20 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 34 , 37 , 41 , 45, 46, 47 , 50 , 51 , 54 , 55 , 59 , 63 , 65 , 67 , 68 , 70, 71, 72, 73 , 76 The pooled prevalence of nausea/vomiting was 7.8% (95% CI, 7.1%–8.5%). A subgroup analysis of 1901 patients from 7 studies (including patients from Germany, Singapore, United States, Australia, and The Netherlands) demonstrated a higher pooled prevalence of 14.9% (95% CI, 13.3%–16.6%).37 , 46 , 47 , 59 , 63 , 68 , 70 This is in comparison to the prevalence of symptoms in studies from China, which was 5.2% (95% CI, 4.4%–5.9%) (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 7).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the prevalence of nausea/vomiting in all patients.

Supplementary Figure 7.

Forest plot of the prevalence of nausea/vomiting as one of the initial symptoms in all patients regardless of hospitalization status.

Abdominal pain

A total of 15 studies including 4031 COVID-19 patients (confirmed by laboratory RT-PCR testing) were included in the overall analysis for abdominal pain.21 , 23 , 27 , 37 , 50 , 54 , 55 , 59 , 63 , 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 , 76 The pooled prevalence of abdominal pain was 3.6% (95% CI, 3.0%–4.3%). A subgroup analysis of 1584 patients from the United States, Australia, South Korea, and The Netherlands, demonstrated a slightly higher pooled prevalence of 5.3% (95% CI, 4.2%–6.6)% compared with studies from China 2.7% (95% CI, 2.0%–3.4%), which included 10 studies of 2447 patients.37 , 59 , 63 , 69 , 70 The symptoms were variably described as stomachache, epigastric pain, and abdominal discomfort, without further details regarding the quality or nature of pain (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure 8).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the prevalence of abdominal pain in all patients.

Supplementary Figure 8.

Forest plot of the prevalence of abdominal pain as one of the initial symptoms in all patients regardless of hospitalization status.

Stool shedding

Our study selection criteria prioritized including studies with diarrhea as a GI manifestation and avoiding overlap in populations and, therefore, did not include a comprehensive set of studies reporting on stool shedding. A recently published systematic review by Cheung et al10 found a 48.1% (95% CI, 38.3%–59.7%) pooled prevalence of stool samples positive for virus RNA in 12 studies. Stool RNA was positive in 70.3% of samples taken from patients after respiratory specimens were no longer positive for the virus.

From the 57 studies included in our analysis, 4 studies reported on presence of viral RNA in stool.24 , 32 , 57 , 68 Of these, 3 studies were published after the systematic review by Cheung et al.10 First, Dreher et al68 conducted a retrospective cohort study in Germany, stratifying patients by presence of acute respiratory distress syndrome. In this study, 8 of 50 patients had diarrhea, and stool PCR was positive in 15 of 50 patients. In a US study by Kujawski et al,57 stool PCR was positive in 7 of 10 patients. Finally, in a case series from Germany by Wolfel et al,32 the authors not only examined stool RNA but also tried to isolate virus from laboratory specimens. In this study, 2 of 9 patients had diarrhea as an initial symptom and stool PCR remained positive for up to 11 days, but notably, the authors were unable to isolate infectious virus, despite a high stool viral RNA load, even though the virus was successfully isolated from respiratory specimens. The authors concluded that stool is not a primary source of spread of infection.32 Conversely, in a letter published by Wang et al,78 the authors collected 1070 specimens from 205 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and 44 of 153 stool specimens (29%) were positive for viral RNA. Four specimens with high copy numbers were cultured and electron microscopy was performed to detect live virus, which was observed in the stool from 2 patients who did not have diarrhea. The authors concluded that although this does not confer infectivity, it raised the possibility of fecal–oral transmission.78 The small sample size of the reports that assessed the presence of live virus in stool combined with the conflicting findings limit our certainty in the evidence and thus the question of fecal–oral transmission remains unsettled.

What Are the Liver Manifestations of COVID-19?

Based on our inclusion strategy, 34 of the 57 studies (60%) reported any data on liver abnormalities.20, 21, 22 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 34, 35, 36 , 38 , 41, 42, 43 , 45 , 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 , 55 , 57 , 60 , 61 , 63 , 65, 66, 67 , 70, 71, 72 , 75 , 76 The majority of the studies that reported data on LFTs only reported continuous summary statistics (median and interquartile range) without reporting the number of patients with abnormal levels. Abnormal aspartate transaminase (AST), defined as any value above the upper limit of normal (ULN), was reported in 15.0% (95% CI, 13.6%– 16.5) of patients across 16 studies, including 2514 COVID-19 patients. Abnormal alanine transaminase (ALT), defined as any value above the ULN, was reported in 15.0% (95% CI, 13.6%–16.4%) of patients across 17 studies including 2711 COVID-19 patients. Abnormal bilirubin, defined as any value above the ULN, was reported in 16.7% (95% CI, 15.0%–18.5%) of patients across 10 studies including 1841 COVID-19 patients. All patients had confirmed COVID-19 by laboratory RT-PCR testing.

The study by Cholankeril et al70 reported that 26 of 65 patients (40%) had abnormal liver enzymes and 22 of them had normal baseline liver enzymes. None of the remaining studies provided any information regarding the status of LFTs before the infection. One study by Fu et al65 reported summary statistics (median and interquartile range) of LFTs for 23 patients on admission and discharge with no clinically important changes. However, they did not provide the number of patients who presented with normal or abnormal LFTs and how many of them improved or worsened. None of the included studies reported the workup of LFTs in the settings of COVID-19 or assessed whether they were related to alternative etiologies, especially medications. Thirteen studies reported on the association between the presence of liver injury at presentation and severity of disease or outcomes. Most of them reported the results of univariate analyses.20 , 22 , 27 , 38 , 45 , 48 , 51 , 53 , 55 , 63 , 67 , 71 , 72 The study by Hajifathalian et al63 reported the results of multivariate analyses that included multiple variables and showed liver injury at presentation was associated with high risk for admission, as well as higher risk of intensive care unit admission and/or death as a composite outcome63 (Supplementary Figure 10, Supplementary Figure 11, Supplementary Figure 9).

Supplementary Figure 10.

Forest plot of the prevalence of elevated ALT.

Supplementary Figure 11.

Forest plot of the prevalence of elevated total bilirubin.

Supplementary Figure 9.

Forest plot of the prevalence of elevated AST.

Rationale for Best Practice Statements

-

1.

In outpatients with new-onset diarrhea, ascertain information about high-risk contact exposure; obtain a detailed history of symptoms associated with COVID-19, including fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, or new loss of taste or smell; and obtain a thorough history for other Gl symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

-

2.

In outpatients with new-onset Gl symptoms (eg, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea), monitor for symptoms associated with COVID-19, as GI symptoms may precede COVID-related symptoms by a few days. In a high COVID-19 prevalence setting, COVID-19 testing should be considered.

-

3.

In hospitalized patients with suspected or known COVID-19, obtain a thorough history of GI symptoms (ie, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea), including onset, characteristics, duration, and severity.

The overall prevalence of GI symptoms in context of COVID-19, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, is lower than estimated previously.10 It is important to note that the majority of studies were focused on hospitalized patients with COVID-19, and the prevalence of diarrhea in patients with mild symptoms who were not hospitalized is not known. Therefore, the reported prevalence rates may represent either an overestimate or underestimate. Information about the frequency and severity of diarrhea symptoms was inadequately reported in the majority of studies.

Based on our analysis, among hospitalized patients, the prevalence of diarrhea as the only presenting symptom in the absence of other COVID-related symptoms was very low. The majority of patients with diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting also presented with accompanying symptoms typically associated with COVID-19. In a handful of studies, diarrhea and nausea preceded the development of other COVID-19–related symptoms. In a US case–control study of 278 COVID-19 patients, patients with GI symptoms were more likely to have illness duration of 1 week or longer (33%) compared to patients without GI symptoms (22%). This may have been attributable to a delay in testing.47 Therefore, in high prevalence settings, among patients presenting with new-onset diarrhea, monitoring for the development of COVID-19 symptoms and considering referring patients for COVID-testing is reasonable, especially if testing capacity is not limited.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recently expanded the criteria for COVID-19 testing to include presence of olfactory and gustatory symptoms as triggers for testing, as these symptoms have been demonstrated to occur in up to 80% of patients.79 As of April 19, 2020, diarrhea as an initial preceding symptom of COVID-19 has not been included on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention symptom checklist.

To more accurately inform our understanding of the true prevalence of diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting as a manifestation of COVID-19, it is critical to systematically collect information about onset of diarrhea; duration of symptoms; and documentation of whether and how long symptoms of diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting precede upper respiratory infection symptoms. Therefore, we advise health care professionals and researchers to obtain a thorough review of systems, systematically inquire about respiratory and GI symptoms, and ascertain information about exposure.

-

4.

There is presently inadequate evidence to support stool testing for diagnosis or monitoring of COVID-19 as part of routine clinical practice.

While stool shedding has been reported in a prior meta-analysis in 48.1% of specimens, 2 small case series showed conflicting findings about the presence of living virus in stool.10 , 32 , 78 Therefore, stool infectivity and transmission have not been confirmed. Further studies are needed to determine whether isolated virus from stool specimens confers infectivity and determine the role of stool testing is in patients with COVID-19.

-

5.

In patients (outpatients or inpatients) with elevated LFTs in context of suspected or known COVID-19, evaluate for alternative etiologies.

-

6.

In hospitalized patients with suspected or known COVID-19, obtain baseline LFTs at the time of admission and consider LFT monitoring throughout the hospitalization, particularly in the context of drug treatment for COVID-19.

-

7.

In hospitalized patients undergoing drug treatment for COVID-19, evaluate for treatment-related Gl and hepatic adverse effects.

Abnormal LFTs were reported in approximately 15% of patients across the pooled studies, but with variable reporting of mean or median values for the whole sample of patients. While the studies used in this analysis helped us to better understand the prevalence of abnormal LFTs among hospitalized patients, LFT abnormalities were not consistently reported across studies. Also, many of the studies in this analysis did not report on how many patients had underlying liver disease and whether these patients were at an elevated risk of having increased LFTs in the setting of COVID-19 infection. Furthermore, diagnostic evaluation of abnormal LFTs on admission was not performed routinely, such as testing for viral hepatitis or other etiologies. The available studies suggest that abnormal LFTs are more commonly attributable to secondary effects (eg, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, cytokine storm, ischemic hepatitis/shock, sepsis, and drug hepatotoxicity) than primary virus-mediated hepatocellular injury.7 , 9 , 80 However, liver histopathology from patients with COVID-19 have revealed mild lobular and portal inflammation and microvesicular steatosis suggestive of either virally mediated or drug-induced liver injury.81 In addition, some studies have revealed that abnormal LFTs at hospital admission may be associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 (odds ratio, 2.73; 95% CI, 1.19–6.3).9 Therefore, we advise checking baseline LFTs in all patients on admission and monitoring of LFTs throughout the hospitalization, particularly in patients undergoing drug therapy for COVID-19 associated with potential hepatotoxicity. We additionally advise that all patients with abnormal LFTs undergo an evaluation to investigate non–COVID-19 causes of liver disease.

What Are Common Gastrointestinal/Liver Adverse Effects of COVID-19 Treatments?

`There are currently no US Food and Drug Administration–approved routine treatments for COVID-19. The FDA has issued an emergency use authorization for 3 therapies: choloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, and convalescent plasma.82 In China and Japan, favipiravir has been approved for the treatment of COVID-19. Numerous medications are under investigation; the World Health Organization is spearheading a multinational, multicenter trial for the 5 treatments highlighted below.83 We aim to provide a summary of the Gl and liver adverse effects of the most commonly utilized medications for COVID-19 at this time, irrespective of their efficacy. Medication GI-related adverse events are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 (direct evidence sources and indirect evidence sources).

Antimalarial Medications

Although efficacy and subsequent optimal dosing in COVID-19 is still under investigation, both chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are currently FDA-approved in the United States for other indications (ie, malaria and systemic lupus erythematosus) and now have an emergency use authorization for use in COVID-19.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine

Both chloroquines have reported infrequent Gl adverse effects (ie, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea).84 , 85 The National Institute of Health LiverTox resource rates both drugs with a likelihood score of D (possible rare cause of clinically apparent liver injury).86 Chloroquine is rarely linked to aminotransferase elevations or clinically apparent liver injury. In patients with acute intermittent porphyria or porphyria cutanea tarda, it can trigger a hypersensitivity attack with fever and serum aminotransferase elevations, sometimes resulting in jaundice. This is seen less commonly with hydroxychloroquine. Such reactions are thought to be hypersensitivity reactions and there is no known cross-reactivity in liver injury between hydroxychloroquine and choloroquine. Hydroxychloroquine is known to concentrate in the liver, thus patients with hepatitis or other hepatic diseases, or patients taking other known hepatotoxic drugs, should exercise caution. In addition, cardiac conduction defects leading to clinically relevant arrhythmias are an important adverse effect of these medications.

Antiviral Medications

Remdesivir

Limited data regarding GI adverse events are available, as phase 3 trials are still underway. Based on studies regarding Ebola, there have been reports of elevated transaminases, although the severity and incidence have not been quantified.87 There is 1 published case series (n = 53) on compassionate use of remdesivir in COVID-19.88 In this study, the most common adverse effects were notably Gl and hepatotoxicity. Five of 53 patients (9%) experienced diarrhea and 12 of 53 patients (23%) had reported elevations in hepatic enzymes associated with remdesivir. Of 4 patients (8%) who discontinued treatment prematurely, 2 were due to elevated aminotransferases.

Lopinavir/ritonavir

The combination lopinavir/ritonavir is FDA-approved for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). More recently, it was utilized to treat MERS and SARS. There is 1 trial by Cao et al89 that randomized 199 hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 to receive treatment to lopinavir/ritonavir (n = 99) or placebo (n = 100) for 14 days. GI adverse events were most common among those in the treatment group, and were the primary reason for medication discontinuation; of patients receiving lopinavir/ritonavir, there were 9.5% (9 of 99) with nausea, 6.3% (6 of 99) with vomiting, 4.2% (4 of 99) with diarrhea, 4.2% (4 of 99) with abdominal discomfort, 4.2% (4 of 99) with reported stomach ache, and 4.2% (4 of 99) with diarrhea. Additionally, there were 2 serious adverse events of acute gastritis, which both led to drug discontinuation. When lopinavir/ritonavir is used in patients with HIV, diarrhea is the most common GI adverse events (10%–30%), with greater prevalence among those receiving higher doses. Other GI adverse events in HIV are similar to Cao et al’s RCT, with nausea in 5%–15% and vomiting in 5%–10% of patients90 (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Gastrointestinal Treatment Adverse Effects of Currently Utilized COVID-19 Therapies

| Medication type | Medication name | Adverse effects |

Major drug–drug interactions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | Hepatic | |||

| Antimalarial | Chloroquine Hydroxychloroquine |

Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea reported; frequency not defined | Likelihood score: D (possible rare cause of clinically apparent liver injury). Description: Rare elevations in aminotransferases. Most reactions are hypersensitivity with no known cross reactivity to hepatic injury. If this occurs, reasonable to switch between chloroquine therapies. |

Substrate for CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 substrate Same as above; also substrate for CYP3A5 and CYP2C8 |

| Antiviral | Remdesivir | Not reported (limited data available) | Likelihood score: Not scored. Description: Hepatotoxicity reported; frequency not yet known. |

Not a significant inducer/inhibitor of CYP enzymes |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | Nausea and vomiting: 5%–10% (higher in children: 20%) Abdominal pain: 1%–10% Diarrhea: 10%–30% + dose-dependent Other: dysguesia in adults <2%, children: 25%, increased serum amylase, lipase: 3%–8%. |

Likelihood score: D (possible, rare cause of clinically apparent liver injury). Description: Hepatotoxicity ranges from mild elevations in aminotransferases to acute liver failure. Recovery takes 1–2 mo. Re-challenging may lead to recurrence and should be avoided if possible. |

Substrate for: CYP3A4, CYP2D6 P-gp Inducer for: CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, UGT1A1 Inhibitor for: CYP3A4 |

|

| Favipiravir | Nausea/vomiting: 5%–15% Diarrhea: 5% Limited data available |

Likelihood score: Not scored Description: 3% prevalence, but few data available. |

Inhibitor for: CYP2C8 and aldehyde oxidase Metabolized by xanthine oxidase and aldehyde oxidase |

|

The Cao et al89 RCT did not show a significant increase in hepatotoxicity in the treatment compared to the control group. However, in patients with HIV, there is a well-documented known risk of hepatotoxicity, with liver injury severity ranging from mild enzyme elevations to acute liver failure.91 Moderate-to-severe elevations in serum aminotransferases, defined as more than 5 times the ULN, are found in 3%–10%.91 Rates may be higher in patients with concurrent HIV and hepatitis C virus co-infection. In some cases, mild asymptomatic elevations are self-limited and can resolve with continuation of the medication, but re-challenging the medication can also lead to recurrence and, therefore, should be avoided when possible. Acute liver failure, although reported, is rare. Ritonavir has potent effects on cytochrome P450 and therefore affects drug levels of a large number of medications typically given in GI practices.

Favipiravir

There are 2 published studies on favipiravir in COVID-19. The first is an open-label RCT for favipiravir vs arbidol conducted in Wuhan, China by Chen et al.92 This study reported digestive tract reactions, including nausea, “anti-acid,” or flatulence in 13.79% (16 of 116) of the favipiravir group. Hepatotoxicity characterized by any elevation in AST or ALT was reported in 7.76% (9 of 116). The second is an open-label control study of favipiravir or lopinavir/ritonavir, both used in conjunction with interferon alfa, for COVID-19 by Cai et al,93 which reported diarrhea in 5.7% (2 of 35) and liver injury in 2.9% (1 of 35) (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Limitations of the Evidence on Gastrointestinal and Liver Manifestations in Patients With COVID-19 Infection

The individual studies in our analysis were at high risk of bias. The majority of studies reported on cohorts of patients based on inclusion dates and did not specify whether these were consecutive patients. There was an inconsistent assessment of symptoms and/or laboratory tests with missing data, and none of the studies reported whether patients were systematically evaluated for GI symptoms on admission. Most studies did not report on the duration of the GI symptoms preceding the presentation. When GI symptoms were reported, it was difficult to discern whether these were isolated symptoms or whether patients also had concurrent typical COVID-19 symptoms (eg, fever cough or shortness of breath). LFTs were mostly reported as the mean/median value of the entire cohort and without cutoff values for the institution. Many of the studies did not report on underlying chronic GI or liver diseases. There was a lot of heterogeneity in our pooled estimates that could not be explained by our subgroup analysis based on geographic location. Lastly, the data on prognosis were especially difficult to analyze due to insufficient follow-up of the patients (the majority of the patients were still hospitalized at the time of publication). Finally, there was no stratification of GI-related symptoms and severity of COVID-19 or patient important outcomes, such as need for intensive care unit or survival.

There may be additional limitations of our findings based on our analysis. Due to concerns about overlapping cohorts, we used a hierarchical framework to identify unique cohorts based on the number of patients and the hospitals to analyze the prevalence of GI and liver symptoms. It is possible that we excluded relevant studies that provided more granularity regarding the GI and liver manifestations, or had more systematic assessment of outcomes. As a result, this may have led to an over- or underestimation of the pooled effect estimates. However, we have high confidence that we were able to eliminate the counting of some patients in more than 1 report by using our selection framework, unless they were transferred from one hospital to another. An important strength of this study is the appropriate statistical analysis used to pool proportions. We also reviewed gray literature from prepublication repositories, which allowed us to include a large number of studies that have not been published yet, with data from a total of 10,890 unique COVID-19 patients being included in this work. Lastly, we tried to narratively describe studies that informed us on the type of diarrhea symptoms; whether diarrhea was reported as the only presenting symptom; or diarrhea as the initial symptom that preceded other symptoms. Based on our study selection process, we may have missed studies, including smaller case series that reported on this information, and studies that were published after our inclusion period, in light of the exponential number of studies in press, under review, and on preprint servers.

Limitations of Current Evidence on Treatment-Related Adverse Effects

Most of the information regarding Gl adverse events come from indirect evidence from medications that are FDA-approved for other indications, such as the chloroquines and lopinavir/ritonavir. In particular, Gl adverse events are poorly understood for both favipiravir and remdesivir, including the frequency and severity of aminotransferase elevations and incidence of Gl manifestations. As ongoing clinical trials are completed regarding efficacy of therapy, additional data regarding Gl adverse events will emerge.

Evidence Gaps and Guidance for Research

There is insufficient evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on subgroups of patients, such as patients with inflammatory bowel disease, chronic liver disease, or liver transplant recipients on chronic immunosuppression. Early data do not indicate excess risk among patients with inflammatory bowel disease.94, 95, 96, 97, 98 A number of international registries have been established that will provide extremely valuable information about COVID-19 in these potentially vulnerable populations (www.covidibd.org; covidcirrhosis.web.unc.edu; www.gi-covid19.org). Other clinical decisions, including optimal medication management and treatment decisions, are still under investigation. We encourage clinicians to contribute to these registries to further enhance understanding in these subpopulations. Table 4 provides guidance for future studies of GI manifestations in patients with COVID-19 or other similar pathogens.

Table 4.

Guidance and Research Considerations for Future Studies of COVID-19a

| Study design | A prospective inception cohort study is a favorable study design. Another study design that is informative especially when there is a need for rapid data evaluation is a retrospective inception cohort study. |

| Participants | Enrollment of consecutive patients beginning at pandemic onset. Specific set of symptoms that are predictive of COVID-19 infection, all symptoms should be systematically collected on presentation and before COVID-19 diagnosis is established.

Investigators should consider stratification by outpatients vs inpatients |

| Laboratory | Standardized laboratory confirmation should be based on nucleic acid amplification testing for SARS-CoV-2 on respiratory specimen rather than relying on radiologic suspicion on imaging studies, which are less specific LFTs should be obtained on admission and followed throughout the hospitalization. Changes in LFTs should be reported as normal/abnormal and the cutoff for abnormal should be specified, rather than mean and median at the individual patient level Pattern of LFTs abnormalities, hepatocellular vs cholestatic, should be reported as well as the evaluation performed to work up the abnormalities Baseline LFTs (prior to developing COVID-19), changes during the duration of the disease, and after resolution should be reported. Report stool RNA testing, when available, and presence of GI symptoms at the time of testing |

| Disease severity | Use of standardized disease severity definitions, for example, as per World Health Organization–China Joint Mission100:

|

| Outcomes | Outcomes should focus on patient-important outcomes, such as death, clinical improvement or disease worsening/progression, hospital discharge; include clinical definitions (eg, threshold reached for intubation); select sufficient follow-up time to ensure outcome is obtainable. |

| Analysis | Analysis should attempt to control for confounding variables; analysis of risk factors should include univariate followed by multivariate analyses to identify independent risk factors predicting more severe disease and poor outcomes |

aIn the table, we specifically refer to COVID-19, but this guidance applies to any future pathogen similar to COVID-19 that presents as a viral illness with potential GI and liver manifestations.

Finally, peer-review remains critical to the process of disseminating information. Journals should add resources to expedite reviews by increasing the number of editors and reviewers to shorten the review process; maintain accuracy, high quality, and details of the data reported; as well as to avoid overlap in patients between studies or multiple studies being published on the same cohort.99

Update

Recommendations in this document may not be valid in the near future. We will conduct periodic reviews of the literature and monitor the evidence to determine whether recommendations require modification. Based on the rapidly evolving nature of this pandemic, this guideline will likely need to be updated within the next few months.

Conclusions

The global COVID-19 pandemic due to SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with significant morbidity and mortality due to severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiorgan failure. Although fever, cough, and shortness of breath remain the most common presenting symptoms in affected individuals, emerging data suggest that nonpulmonary symptoms affecting the GI tract and liver may be observed. Based on systematic review and meta-analysis of 47 studies and 10,890 unique patients, gastrointestinal symptoms (ie, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea) are observed in <10% of patients with COVID-19, and abnormal liver enzymes and tests (AST, ALT, and bilirubin) are observed in approximately 15%–20% of patients with COVID-19. These findings inform time-sensitive clinical guidance in the context of this pandemic to pursue careful evaluation of patients with new-onset gastrointestinal symptoms for classic and atypical symptoms of COVID-19. All hospitalized patients with COVID-19 may benefit from liver enzyme monitoring, particularly in the context of drug treatment with known hepatotoxic potential. Further research is needed to clarify the implications of SARS-CoV-2 in stool and potential impact on transmission and clinical management.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest All members were required to complete the disclosure statement. These statements are maintained at the AGA headquarters in Bethesda, Maryland, and pertinent disclosures are published with this report. None of the panel members had any conflict relevant to this guideline.

Funding This document represents the official recommendations of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and was developed by members of the AGA Clinical Guideline Committee and Clinical Practice Update Committee and approved by the AGA Governing Board. No internal or external funding was provided for the development of this guideline. Expiration date: 3 months.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.001.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies

| Study characteristics | Patient characteristics | Gastrointestinal manifestations | Liver Manifestationsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hubei Province, China | |||

| Luo, 202050 Zhongnan Hospital (Wuhan) Dates: 01/01/2020-02/20/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 1141 Survival: 3.8% (7/183) death, 96.2% recovered Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 (throat swab RT-PCR). All patients received chest CT. Details only provided for the 183 patients with GI symptoms. Age: m 53.8 y (183 patients) Sex: 44.3% (81/183) females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: NR |

Diarrhea: 6.0% (n = 68) Present on admission Abdominal pain: 3.9% (n = 45) Present on admission Nausea: 11.7% (n = 134) Present on admission Vomiting: 10.4% (119) Present on admission Nausea and vomiting: 3.2% (n = 37) Present on admission 183 patients presented with GI symptoms only (diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and/or loss of appetite). 96% of them had lung lesions on chest CT |

AST (183 patients) m 65.8 ± 12.7 ALT (183 patients) m 66.4 ± 13.2 |

| Zhou, 202020 Jinyintan Hospital (Wuhan) Dates: 12/29/2019-01/31/2020 Last follow-up: 01/31/2020 |

n = 191 Survival: 28.3% death, 71.8% discharged Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 (confirmed with RT-PCR) who died or were discharged. Patients without key information excluded (9). Age: M 56 y (IQR, 46–67 y) Sex: 37.7% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: General 28%, severe: 35%, critical 28% |

Diarrhea: 4.7% (9/191) Present on admission 2 died and 7 discharged Nausea/vomiting: 3.7% (7/191) Present on admission 3 died and 4 discharged Abdominal pain: NR |

AST: NR ALT >40: 31.2% (59/189) 26 died and 33 discharged Total bilirubin: NR |

| Zhang, 202023 Wuhan No. 7 Hospital (Wuhan) Dates: 1/16/2020-02/03/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 140 Survival: NR Inclusion: Inpatient with COVID-19 (pharyngeal swab PCR) based on symptoms and chest x-ray. Age: 57 y (range, 25–87 y) Sex: 49.3% females GI/liver comorbidities: 5.7% fatty liver and abnormal liver function, 5.0% chronic gastritis and gastric ulcer, 4.3% cholelithiasis, 6.4% cholecystectomy 5.0% appendectomy, 0.7% hemorrhoidectomy, 4.3% tumor surgery Disease severity: severe 41.4% and nonsevere 58.6% |

Diarrhea: 12.9% (18/139) Present on admission 9/82 nonsevere cases and 9/57 severe cases Nausea: 17.3% (24/139) Present on admission 19/82 nonsevere cases and 5/57 severe cases Vomiting: 5.0% (7/139) Present on admission 5/82 nonsevere cases and 2/57 severe cases Belching 5.0% (7/139) Present on admission 4/82 nonsevere cases and 3/57 severe cases Abdominal pain: 5.8% (8/139) Present on admission 2/82 nonsevere cases and 6/57 severe cases Other pathogens were detected including Mycoplasma pneumoniae in 5, respiratory syncytial virus in 1, Epstein-Barr virus in 1. |

AST, ALT, and bilirubin: NR |

| Chen, 202072 Tongji Hospital (Wuhan) Dates: 01/13/2020-02/12/2020 Last follow-up: 02/28/2020 |

n = 274 Survival: 52.2% death, 47.8% recovered Inclusion: Moderate severity, severe or critically ill COVID-19 patients (throat swab or bronchoalveolar lavage RT-PCR) who were deceased or discharged. Age: M 62.0 y (IQR, 44–70 y) sex: 37.6% female GI/liver comorbidities: 4% hepatitis B surface antigen positivity, 1% GI diseases Disease severity: moderate severity, severe or critically ill. |

Diarrhea: 28.1% (n = 77) Present on admission 27/113 deceased and 50/161 discharged Nausea: 8.8% (n = 24) Present on admission 8/113 deceased and 16/161 discharged Vomiting: 5.8% (n = 16) Present on admission 6/113 deceased and 10/161 discharged Abdominal pain: 6.9% (n = 19) Present on admission 6/113 deceased and 13/161 discharged |

AST >40: 30.7% (84) 59/113 deceased and 25/161 discharged M 30 (IQR, 22–46). Deceased M 45 (IQR, 31–67) and discharged M 25 (IQR, 20–33) ALT >41: 21.9% (60) 30/113 deceased and 30/161 discharged M 23 (IQR, 15–38). Deceased M 28 (IQR, 18–47) and discharged M 20 (IQR, 15–32) Bilirubin M 0.6 (IQR, 0.4–0.8). Deceased M 0.7 (IQR, 0.6–1.0) and discharged M 0.5 (IQR, 0.3–0.7) |

| Xu, 202031 Tongji Hospital (Wuhan) Dates: 1/15/2020-2/19/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 1324 Survival: NR Inclusion: Outpatient COVID-19 patients presenting to fever clinic, based on PCR. Age: m 48 ± 15.3 y Sex: 50.8% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: 95.9% light condition, 3.8% severe, 0.3% critical |

Diarrhea: 2.1% (28) Present on admission Loss of appetite: 4.2% Present on admission Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain: NR |

NR |

| Shi, 202042 Renmin Hospital (Wuhan) Dates: 1/1/2020-2/10/2020 Last follow-up: 2/15/2020 |

n = 645 Survival: 7.3% death, 5.1% discharged (416 patients) Inclusion: Inpatient laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, consecutive. Detailed results reported for 416 patients with complete results. Age: M 45–64 y (range, 21–95 y) Sex: 52.9% female GI/liver comorbidities: 1% hepatitis B infection (of 416 patients) Severity: NR |

Diarrhea: 4.5% (29) Present on admission Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting: NR |

AST (416 patients) M 30 (IQR, 22–43). ALT (416 patients) M 28 (IQR, 18–46). Bilirubin: NR |

| Han, 202062 Wuhan No.1 Hospital Dates: 1/4/2020-2/3/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 108 Survival: NR death, NR recovered Inclusion: Inpatients COVID-19 (confirmed by RT-PCR) with mild pneumonia, no history of other lung infection, initial CT performed. Exclusion: CT scans performed as follow-up for COVID-19 pneumonia, or chest CT image quality insufficient for image analysis Age: mean 45 y (range, 21–90 y) Sex: 64.8% females GI/liver comorbidities: Not specified Disease severity: NR |

Diarrhea: 14% (15/108) Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting: NR |

No laboratory data reported |

| Xu, 202030 Union Hospital (Wuhan) Dates: 1/25/2020-2/20/2020 Last follow-up: 2/20/2020 |

n = 355 Survival: NR Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19, confirmed based on RT-PCR. Age: 45.1% aged <50 y, 41.7% aged 50–69 y, 13.2% aged ≥70 y Sex: 45.6% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: 63.1% mild, 16.9% severe, 20% critical |

Diarrhea: 36.6% (130/355) Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting NR |

AST: 28.7% (102/355) m 40.8 (range, 10–475) ALT: 25.6% (91/355) m 35.0 (range, 1–414) Total bilirubin: 18.6% (66/355) m 0.83 (range, 0.1–29.9) |

| Ma, 202049 Wuhan Leishenshan Hospital (Wuhan) Dates: 3/5/2020-3/18/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 81 Survival: NR Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 (RT-PCR on nasal and pharyngeal swabs) Age: M 38 y (IQR, 34.5–42.5 y) Sex: 0% female GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: 2.5% mild, 86.4% moderate, 8.6% severe, 2.5% critical. |

Diarrhea: 7.41% (6/81) Nausea/vomiting: NR Abdominal pain: NR |

AST/ALT - composite report 31/81 abnormal but no threshold AST M 23 (IQR, 12–453) ALT M 43 (IQR, 13–799) Bilirubin: NR |

| Liu, 202054 General Hospital of Central Theater Command of PLA (Wuhan) Dates: 2/6/2020 - 2/14/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 153 (85 tested negative but had symptoms, we did not include those patients) Survival: NR Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 (RT-PCR on pharyngeal swabs) Age: M 55 y (IQR, 38.3–65 y) Sex:39.2% female GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: NR |

Diarrhea: 9.2% (14/153) Present on admission Nausea: 1.3% (2/153) Present on admission Vomiting: 2% (3/153) Present on admission Abdominal pain: 0.4% (1/153) Present on admission |

AST, ALT, and bilirubin: NR |

| Huang, 202061 The Fifth Hospital of Wuhan (Wuhan) Dates: 1/21/2020-2/10/2020 Last follow-up: 2/14/2020 |

n = 36 Survival: 100% death Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 (RT-PCR) Age: mean 69.22 y (SD 9.64 y; range, 50–90 y) Sex:30.56% female GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: NR |

Diarrhea: 8.33% (3/36) Present on admission Nausea: NR Vomiting: NR Abdominal pain: NR |

AST: >40 58.1% (18/31) M 43 (IQR, 30–51) ALT: >50 13.3% (4/30) M 26 (IQR, 18–38) Bilirubin: >25 12.9% (4/31) M 11.2 (IQR, 7.5–19.2) |

| Mao, 202048 Union Hospital (Wuhan) Dates: 1/16/2020-2/19/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 214 Survival: 1 died but not fully reported. Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 (RT-PCR from throat) Age: m 52.7 ± 15.5 y Sex: 59.3% female GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: 58.9% nonsevere, 41.1% severe |

Diarrhea: 19.2% (41/214) Present on admission Severe disease 14.8% (13/88), nonsevere disease 22.2% (28/126) Abdominal pain: 4.7% (10/214), not included in the analysis Present on admission Severe disease 6.8% (6/88), nonsevere disease 3.2% (4/126) Nausea and vomiting: NR |

AST 26 (8–8191) Severe 34 (8–8191), non-severe 23 (9–244) ALT 26 (5–1933) Severe 32.5 (5–1933), non-severe 23 (6–261) |

| Ai, 202076 Xiangyang No.1 People’s Hospital Dates: Cross-sectional study 2/9/2020 |

n = 102 Survival: 2.9% died, 6.9% survived, 90.2% still hospitalized Inclusion: Inpatients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 Age: m 50.4 ± 16.9 y Sex: 49.1% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: NR |

Diarrhea: 14.3% (15) Present on admission Diarrhea was the first symptom in 2 patients Nausea: 8.8% (9) Present on admission Vomiting: 2.0% (2) Present on admission Abdominal pain: 2.9% (3) Present on admission |

AST >40: 25.5% (26/102) Mean 30.59 (SD 15.03) ALT >50: 19.6% (20/102) Mean 27.77 (SD 21.13) Total bilirubin NR |

| Liu, 202052 Central Hospital of Wuhan (Wuhan) Dates: 1/2/2020-2/1/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 109 Survival: 28.4% died, NR otherwise Inclusion: Inpatient with COVID-19 confirmed based on RT-PCR on throat swab Age: M 62.5 y (IQR, 47.25–65 y) Sex: 33.3% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: NR |

Diarrhea: 11% (12) Present on admission 6/12 with ARDS and 6/12 with no ARDS Nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain: NR |

AST: M 30 (IQR, 21–40) No ARDS 29 (19–38); ARDS 31 (25–44) ALT: M 23 (IQR, 15–36) No ARDS 23 (14–41); ARDS 24 (16–31) Total bilirubin: NR |

| Shu, 202041 Cabin Hospital of Wuhan Stadium (Wuhan) Dates: 2/13/2020-2/29/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 545 Survival: 85.9% discharged, 14.1% still hospitalized, 0% died Inclusion: Inpatient with COVID-19 confirmed based on RT-PCR. Severe cases requiring transfer were excluded. Age: M 50 y (IQR, 38–58 y) Sex: 51.2% females GI/liver comorbidities: 0 chronic liver disease Disease severity: 2.9% mild, 97.1% moderate, 0 severe (excluded). |

Diarrhea: 8.9% (49) Present on admission Nausea or vomiting: 0% (0) Present on admission |

AST >45: 6.4% (35) M 32.1 (IQR, 24.5–36.4) ALT >50: 7.5% (41) M 34.6 (IQR, 26.2–42.3) Bilirubin >1.2: 34.7% (189) M 1.1 (IQR, 0.8–1.3) |

| Wei, 202034 Wuhan Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine Hospital (Wuhan) Dates: 2/1/2020-2/28/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 100 Survival: 3% died, 1% discharged, 96% still hospitalized. Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 confirmed based on RT-PCR. Only mild cases. Age: m 49.1 ± 17.2 y Sex: 60% females GI/liver comorbidities: 9% digestive system diseases, 6% chronic gastritis Disease severity: 100% mild. |

Diarrhea: 2% (2) Present on admission Vomiting: 2% (2) Present on admission |

AST elevated: 5 (5%) ALT elevated: 17 (17%) Total bilirubin abnormal: 0 (0%) |

| Other Chinese Provinces | |||

| Chen, 202073 The First Affiliated Hospital of Wanan Medical College (Wuhu) Anhui Dates: NA (Case series) |

n = 9 Survival: 100% discharged Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 confirmed on RT-PCR via swab Age: range, 25–56 y Sex: 44.4% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: 55.6% moderately ill and 44.4% severely ill |

Diarrhea: 22.2% (2) Nausea/vomiting: 0% (0) Abdominal pain: 0% (0) |

AST, ALT, and bilirubin: NR |

| Zhao, 202021 First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China (Hefei) Anhui Dates: 1/21/2020-2/16/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 75 Survival: NR Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 based on RT-PCR. Age: M 47 y (IQR, 34–55 y) Sex: 44% females GI/liver comorbidities: chronic liver disease 5.3% Disease severity: NR |

Diarrhea: 9.3% (7) Present on admission Abdominal pain: 1.3% (1) Present on admission Nausea/vomiting: NR |

AST > 40: 18.7% (14) M 27 (IQR, 21–37) ALT >40: 20% (15) M 23 (IQR, 14–43) Bilirubin >1.2: 16% (12) M 0.85 (IQR, 0.65–1.06) ALT, ALT, and total bilirubin were not associated with elevated interleukin-6 (a study outcome) |

| Zhao, 202022 Beijing YouAn Hospital Beijing Dates: 1/21/2020-2/8/2020 Last follow-up: 2/29/2020 |

n = 77 Survival: 6.5% died, 83.1% discharged, 10.4% still hospitalized Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 based on RT-PCR. Age: m 52 ± 2 y Sex: 55.8% females GI/liver comorbidities: 10.4% digestive diseases Disease severity: 74% non-severe, 26% severe |

Diarrhea: 1.3% (1) Present on admission 1/57 nonsevere and 0/20 severe Nausea or vomiting: 7.8% (6) Present on admission 3/57 nonsevere and 3/20 severe Abdominal pain: NR |

AST > 40: 26.0% (20) 11/57 non-severe and 9/20 severe M 19 (IQR, 21–42) ALT >40: 33.8% (26) 17/57 non-severe and 9/20 severe M 28 (IQR, 20–46) Bilirubin NR |

| Yang, 202026 Chinese PLA General Hospital Beijing Dates: 12/272019-2/18/2020 Last follow-up: 2/18/2020 |

n = 55 Survival: 3.6% died Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19, confirmed with RT-PCR. Age: M 44 y (IQR, 34–54 y, range, 3–85 y) Sex: 40% females GI/liver comorbidities: 1.8% chronic liver disease Disease severity: 38.2% mild, 36.4% common, 23.6% severe, and 1.8% extremely severe. |

Diarrhea: 3.6% (2) Present on admission 0/21 of the patients without pneumonia on admission and 2/34 of the patients with pneumonia Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain: NR |

AST, ALT, and bilirubin: NR |

| Li, 202056 The Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing Dates: 1/2020-2/2020 Last follow-up: |

n = 83 Survival: NR Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 and at least one abnormal CT scan. Patients with normal CT were excluded (8). Age: m 45 ± 12.3 y Sex: 47% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: 69.9% ordinary, and 30.1% severe/critical |

Diarrhea and abdominal pain: 8.4% (7) Present on admission Nausea or vomiting: NR |

AST, ALT, and bilirubin: NR |

| Qi, 202045 Chongqing Public Health Medical Center, Chongqing Three Georges Central Hospital, and Qianjiang Central Hospital of Chongqing Chongqing Dates: 1/19/2020-2/16/2020 Last follow-up: 2/16/2020 |

n = 267 Survival: 1.5% died, 38.6% discharged, 59.9% still hospitalized. Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 based on RT-PCR. Excluded patients with missing data (42). Age: M 48 y (IQR, 25–65 y) Sex: 44.2% females GI/liver comorbidities: GI diseases 4.5% Disease severity: 81.3% non-severe and 18.7% severe |

Diarrhea: 3.7% (10) Present on admission 7/217 nonsevere and 3/50 severe Nausea or vomiting: 2.2% (6) Present on admission 5/217 nonsevere and 1/50 severe Anorexia: 17.2% (46) Present on admission 33/217 nonsevere and 13/50 severe Abdominal pain: NR |

AST >35: 7.2% (19) 9/217 non-severe and 10/50 severe ALT >40: 7.5% (20) 10/217 non-severe and 10/50 severe Bilirubin >1.5: 2.2% (6) 3/217 non-severe and 3/50 severe |

| Xu, 202029 Guangzhou Eighth People’s Hospital (Guangzhou) Guangdong Dates: 1/23/2020-2/4/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 90 Survival: NR Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 based on RT-PCR who had baseline chest CT. Age: M 50 y (range, 18–86 y) Sex: 56.7% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: NR |

Diarrhea: 5.6% (5) Vomiting: 5.6% (5) Nausea: 2.2% (2) |

NR |

| Lin, 202055 The Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (Zhuhai) Guangdong Dates: 1/17/2020-2/15/2020 Last follow-up: 2/15/2020 |

n = 95 Survival: 0% died, 38.9% discharged, 61.1% still hospitalized Inclusion: Inpatients with confirmed COVID-19. Age: 45.3 ± 18.3 y Sex: 52.6% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: 78.9% non-severe, 21.1% severe |

Diarrhea: 24.2% (23) 5.2% (5) present on admission. Loose or watery stool, 2-10 bowel movements daily. Vomiting: 4.2% (4) 0% (0) present on admission. Nausea: 17.9% (17) 3.2% (3) present on admission. Abdominal pain: 2.1% (2) 0% (0) present on admission. Epigastric discomfort. 11 patients with GI symptoms did not have pneumonia. Viral RNA detected in 31/65 patients including 22/42 who had GI symptoms and 9/23 who did not have GI symptoms. |

AST >35 for females and >40 for males: 4.2% (4) ALT >40 for females and >50 for males: 5.3% (5) Bilirubin >1.5: 23.2% (22) |

| Wen, 202033 All Shenzhen City Guangdong Dates: 1/1/2020-2/28/2020 Last follow-up: 2/28/2020 |

n = 417 Survival: 0.7% died, 71.7% discharged, 27.6% still hospitalized. Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 based on RT-PCR. Age: m 45.4 y Sex: 52.8% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: 8.9% mild, 82.5% moderate, 8.6% severe/critical |

Diarrhea: 7.0% (29) Present on admission. 23/381 of mild/moderates and 6/36 of severe/critical Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain: NR |

ALT, AST, and bilirubin: NR |

| Xu, 202028 First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou), Dongguan People's Hospital (Dongguan), Foshan First People's Hospital (Foshan), Huizhou Municipal Central Hospital (Huizhou), First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College (Shantou), Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University (Zhanijiang), Zhongshan City People's Hospital (Zhongshan) Guangdong Dates: ?-2/28/2020 Last follow-up: 2/28/2020 |

n = 45 Survival: death 0.2%, 24.4% discharged, 73.3% still hospitalized. Inclusion: Critically ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Age: m 56.7 ± 15.4 y Sex: 35.6% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: 100% critical |

Diarrhea: 0% (0) Present on admission |

AST or ALT >40: 37.8% (17) AST (n = 44) M 27 (IQR, 22.0–39.5) ALT (n = 44) M 29 (IQR, 20.1–50.0) Bilirubin (n = 44) M 0.91 (IQR, 0.61–1.3) |

| Yan, 202027 All Hainan Province Hainan Dates: 1/22/2020-3/13/2020 Last follow-up: 3/13/2020 |

n = 168 Survival: 3.6%, 1.2% still hospitalized, 95.2% discharged. Inclusion: Inpatient with COVID-19 based on RT-PCR. Age: M 51 y (IQR, 36–62 y) Sex: 51.8% females GI/liver comorbidities: 3.6% chronic liver disease Severity: 78.6% nonsevere, 21.4% severe |

Diarrhea: 7.1% (12) Present on admission 8/132 nonsevere, 4/36 severe Vomiting: 4.2% (7) Present on admission 5/132 nonsevere, 2/36 severe Nausea: 5.4% (9) Present on admission 6/132 nonsevere, 3/36 severe Abdominal pain: 4.2% (7) Present on admission 5/132 nonsevere, 2/36 severe |

AST >40: 17.3% (18/104) 7/75 non-severe, 11/29 severe ALT >40: 8.0% (9/112) 5/81 non-severe, 4/31 severe Bilirubin >1.5: 0 M 0.51 (IQR, 0.37–0.78) |

| Wang, 202035 First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (Zhengzhou) Henan Dates: 1/21/2020-2/7/2020 Last follow-up: 2/7/2020 |

n = 18 Survival: 0 died, 33.3% discharged, 66.7% still hospitalized Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 Age: M 39 y (IQR, 29–55 y) Sex: 50% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: NR |

Diarrhea: 16.7% (3) Present on admission Vomiting, nausea, abdominal pain: NR |

AST or ALT elevated: 25% (4) Bilirubin: NR |

| Chen, 202071 First Hospital of Changsha (Changsha) and Loudi Central Hospital (Loudi) Hunan Dates: 1/23/2020-2/14/2020 Last follow-up: 2/202/2020 |

n = 291 Survival: 0.7% died, 54.6% discharged, 44.7% still hospitalized Inclusion: Inpatients with COVID-19 based on RT-PCR Age: M 46 y (IQR, 34–59 y, range, 1–84 y) Sex: 50.2% females GI/liver comorbidities: 5.2% chronic liver disease Disease severity: 10% mild, 72.8% moderate, 17.2% severe/critical |

Diarrhea: 8.6% (25) Present on admission 3/29 mild, 17/212 moderate, 5/50 severe/critical Nausea or vomiting: 5.8% (17) Present on admission 6/29 mild, 9/212 moderate, 2/50 severe/critical Abdominal pain: 0.3% (1) Present on admission 0/29 mild, 0/212 moderate, 1/50 severe/critical |

AST >37: 15.1% (44) 5/29 mild, 23/212 moderate, 16/50 severe/critical M 24.7 (IQR, 19.9–31.4) ALT >42: 10.3% (30) 4/29 mild, 16/212 moderate, 10/50 severe/critical M 20.7 (IQR, 14.9-28.9) Bilirubin >1.2: 9.3% (27) 4/29 mild, 17/212 moderate, 6/50 severe/critical M 0.6 (IQR, 0.5–0.9) |

| Liu, 202053 All Jiangsu Province Jiangsu Dates: 1/10/2020-2/18/2020 Last follow-up: 2/18/2020 |

n = 620 Survival: 0 died, 3.2% in ICU, 56.1% still hospitalized, 40.6% discharged Inclusion: Inpatient with COVID-10 based on RT-PCR. Patients without records excluded. Age: m 44.5 ± 17.2 y Sex: 47.4% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: 15.6% asymptomatic/mild, 75.8% moderate, 8.5% severe/critical |

Diarrhea: 8.5% (53) Present on admission 4/97 asymptomatic/mild, 43/469 moderate, 6/53 severe/critically ill Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain: NR |

AST (387) m 23.3 ± 18.5 m 27.3 ± 14.9 in mild/asymptomatic, 32.3 ± 17.5 in moderate, 42.9 ± 28.6 in severe/critically ill ALT (420) m 31.0 ± 22.4 m 26.8 ± 21.6 in asymptomatic/mild, m 31.2 ± 21.1 in moderate, m 39.3 ± 32.5 in severe/critically ill Bilirubin (460) m 0.6 ± 0.4 m 0.7 ± 0.5 mild/asymptomatic, m 0.6 ± 0.4 moderate, m 0.7 ± 0.4 severe/critically |

| Fan, 202067 Shenyang Chest Hospital (Shenyang) Liaoning Dates: 1/20/2020-3/15/2020 Last follow-up: NR |

n = 55 Survival: 100% recovered Inclusion: Recovered hospitalized COVID-19 patients, based on RT-PCR. Age: m 46.8 y Sex: 45.5% females GI/liver comorbidities: NR Disease severity: 85.4% mild, 14.5% severe |

Diarrhea: 10.9% (6) 4/47 mild/moderate, 2/8 severe/critical Vomiting: 7.3% (4) 2/47 mild/moderate, 2/8 severe/critical Abdominal pain: NR |

ALT m 40.6 m 27.8 in mild/moderate and m 57.1 in severe/critical Bilirubin m 19.5 m 19.0 in mild/moderate and m 22.4 in severe/critical AST: NR |