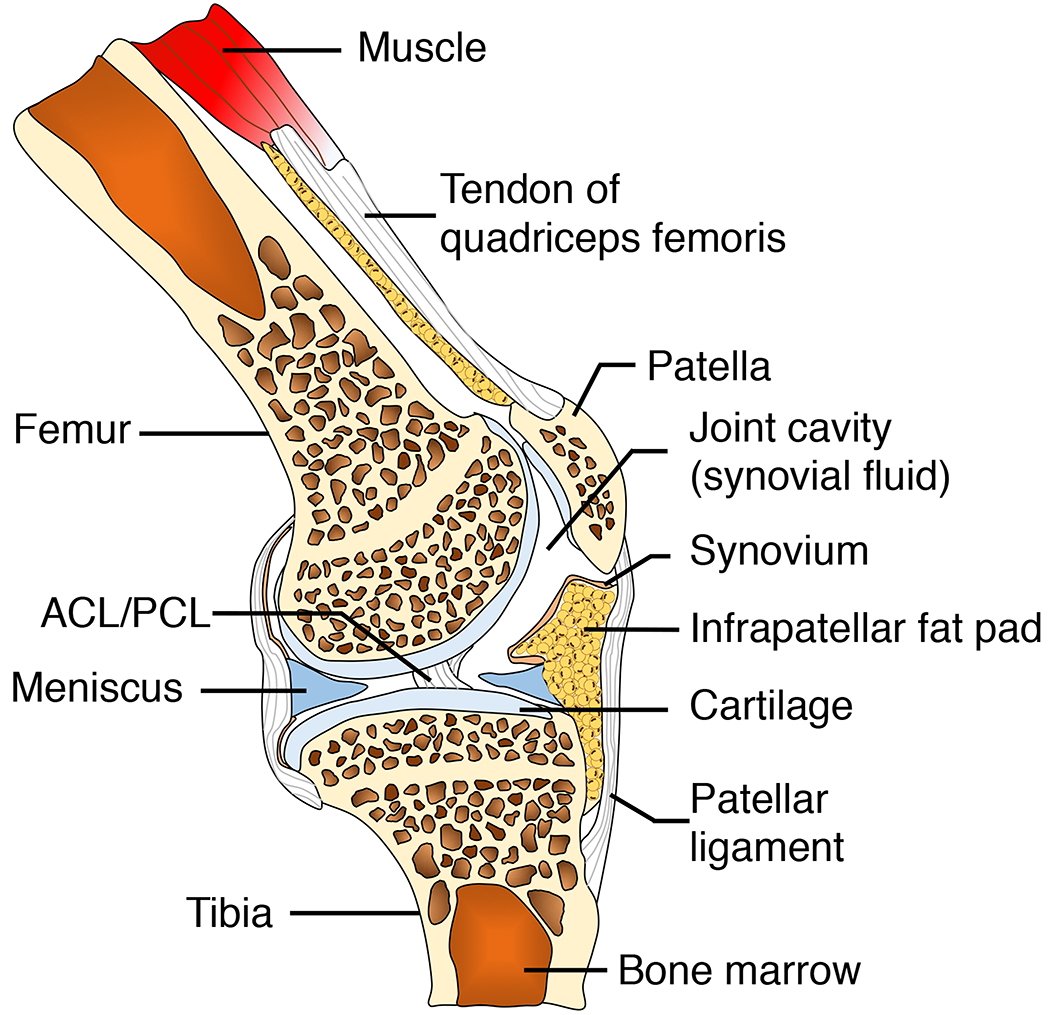

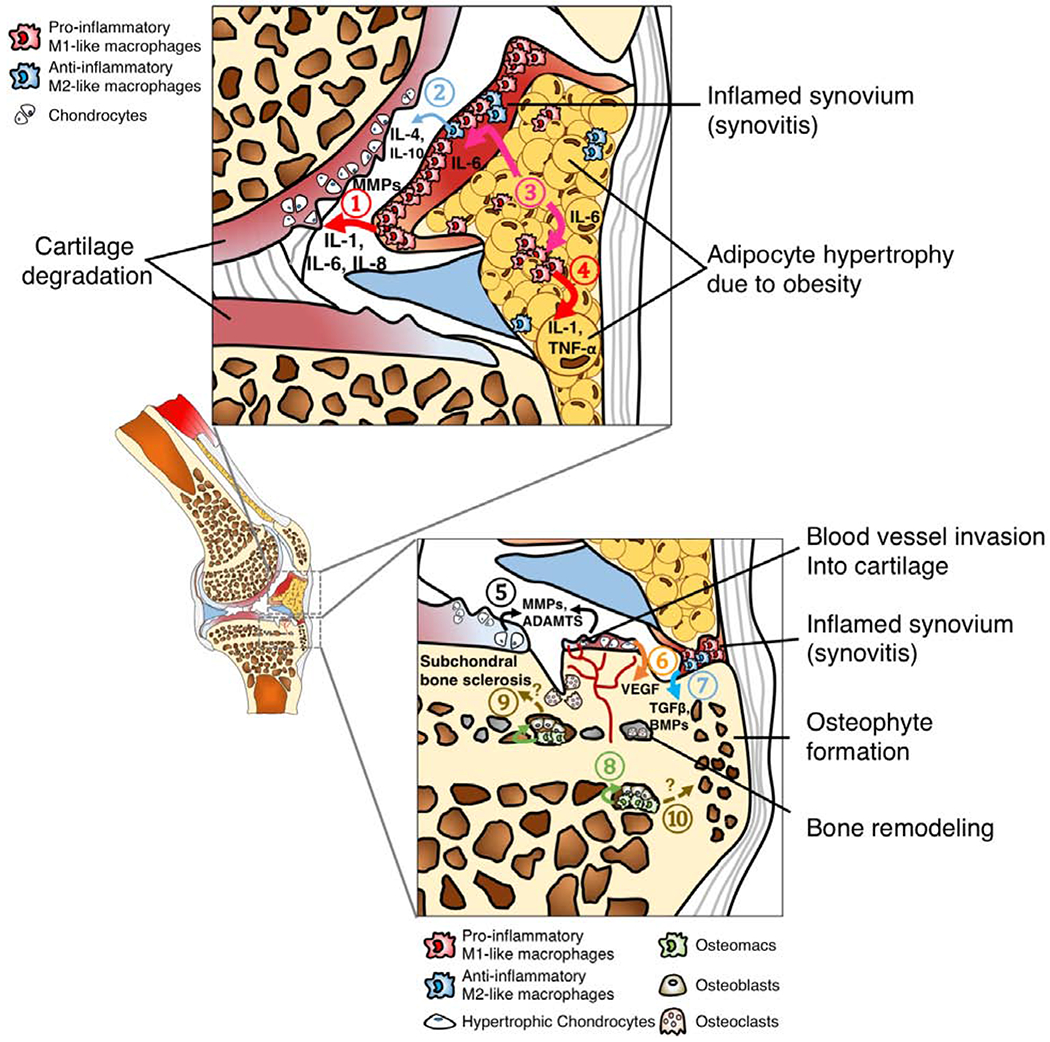

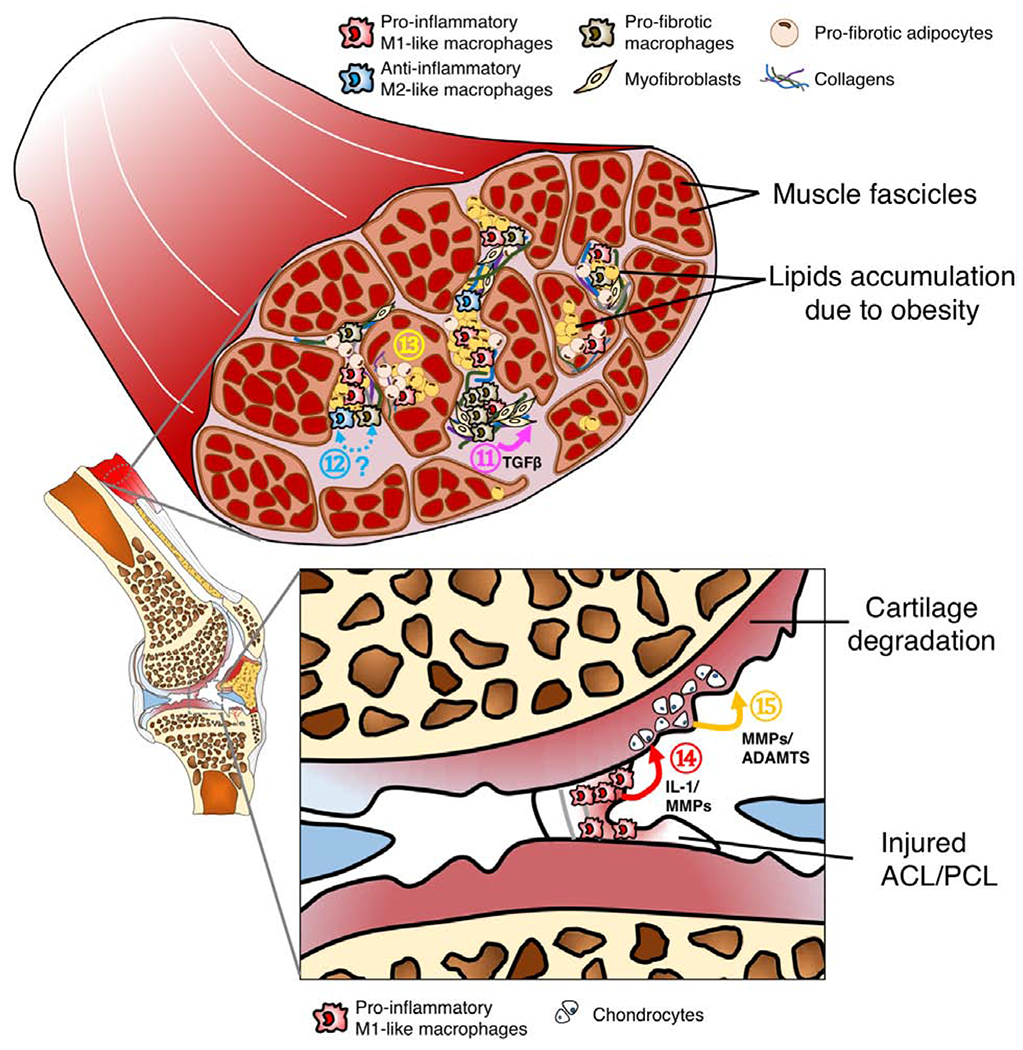

Figure 2.

A. Tissue compartments of a healthy knee joints. ACL: anterior cruciate ligament. PCL: posterior cruciate ligament.

B. Tissue compartments of an OA knee joints. ① Pro-inflammatory M1-like macrophages in the synovial lining layer secrete inflammatory cytokines such IL-1, IL-6 and IL-8, as well as cartilage matrix degradation enzymes including MMPs, leading to cartilage degeneration. Although ② Anti-inflammatory M2-like macrophages can release reparative mediators such as IL-4 and IL-10 into joint synovial fluid, these anti-inflammatory molecules are often not sufficient to encounter the catabolic inflammatory response, partially due to high ratio of M1-like to M2-like macrophages [31]. High-fat diet-induced obesity results in adipocyte hypertrophy in infrapatellar fat pad due to increased lipid storage.③ Hypertrophic adipocytes secrete IL-6, activating ④ macrophages in both synovium and joint fat pad to secrete IL-1 and TNF-α, leading to a vicious inflammatory cycle [103]. ⑤ Chondrocytes in OA cartilage also secrete MMPs and disintegrin metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTs) [104]. Additionally, ⑥ hypertrophic chondrocytes secrete vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) which leads blood vessel invasion into cartilage, an important of step of cartilage and bone remodeling [105]. Bone remodeling in OA can be driven by several factors. For example, ⑦ synovial macrophages, potentially M2-like phenotype, secrete TGFβ and BMPs, facilitating osteophyte formation. Furthermore, ⑧ osteomacs, a recently discovered phenotype of macrophages within bone marrow, form a canopy over osteoblasts, supporting the bone matrix deposition function of osteoblasts. However, whether osteomacs directly contribute ⑨ subchondral bone sclerosis or ⑩ osteophyte formation in OA remains unknown.

C. Tissue compartments of an OA knee joints. It has been suggested that loss of muscle integrity and associated functional deficits due to injury or obesity may alter joint loading, leading to onset of OA. Particularly, ⑪ Pro-fibrotic macrophages activate collagen-producing myofibroblast via the TGFβ signaling pathway. While this reparative process is essential in tissue healing, it may lead to tissue fibrosis if not modulated. ⑫ Currently, the origin and phenotypic plasticity of pro-fibrotic macrophages remains unclear, although some evidence suggests that pro-fibrotic macrophages are associated with anti-inflammatory M2-like macrophages. Interestingly, recent studies demonstrate that bone marrow-derived macrophages can also transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts [106]. Additionally, ⑬ pro-fibrotic adipocytes, a potential phenotypic switch of adipocyte progenitors due to obesity, can also significantly contribute to tissue fibrosis in muscle [107]. Ligament injury often leads to abnormal loading forces on cartilage, predisposing the injured joint to OA development. In addition to altered mechanical loading, macrophage-associated inflammation provides an alternative mechanism for OA pathogenesis post-ligament injury. Specifically, ⑭ Pro-inflammatory M1-like macrophages infiltrate into the injury site, releasing IL-1 and MMPs into joint synovial fluid. ⑮ These pro-inflammatory molecules can activate chondrocytes to secrete more ECM degradation enzymes including MMPs and ADAMTs, further accelerating cartilage degradation.