Abstract

Objective

To discuss the high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients among different clinical types on initial and follow-up CT.

Methods

Seven COVID-19 patients admitted to the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical Collage were enrolled. All patients underwent initial and follow-up chest HRCT. The main CT features and semi-quantitative score which represent disease severity among different clinical types were evaluated.

Result

On initial CT, the main abnormalities observed in common and severe cases respectively were pure ground glass opacities (GGOs) and patchy consolidation surrounded by GGOs. Critical cases had multiple consolidation surrounded by wide range of GGOs distributed in the whole lung fields. The scope and density score in common (4.5 and 5), severe (9.5 and 9.5) and critical (19 and 12) cases were increased by gradient. On follow-up CT, common and severe types manifested as decreasing density of lesion, absorbed consolidation and GGOs. Critical cases showed progression of the disease. The extent and progression scores in common and severe patients were significantly decreased, while the range score of patients with critical disease reached the highest points, accompanied with an increase in the density score.

Conclusion

CT scanning can accurately assess the severity of COVID-19, and help to monitor disease transformation during follow-up among different clinical conditions.

Keywords: coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), Computed tomography, SARS-CoV-2, Follow-up

1. Introduction

In late December 2019, a pneumonia of unknown cause occurred as an outbreak in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China, with clinical symptoms similar to viral pneumonia including fever, cough, and dyspnea [1]. A previously unknown novel virus named as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) with a characteristic crown morphology at electron microscopy scanning was identified as the source of this disease [2]. Subsequently, the pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2 was official termed as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on 11 February 2020 [3]. As of March 13, 2020, a total of 81,003 patients with confirmed COVID-19, including 3181 deaths, have been reported in China [4]. From current knowledge of the cases, most patients with mild and common symptoms have a relatively good prognosis while cases of death are more frequently seen in severe and critical patients, which could progress to severe pneumonia, ARDS and multiple organ failures leading to higher mortality [[5], [6], [7]]. Early diagnosis and accurate staging, therefore, are essential in COVID-19 patients.

Viral nucleic acid detection remains the golden standard in diagnosis of COVID-19 regardless of clinical signs and symptoms, and is also the effective method to screening asymptomatic infection patients. Throat swabs tested by real-time reverse transcription polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) is the most commonly used method [8]. However, previous studies have shown that several defects may limit the clinical application of laboratory tests, including immaturity of the nucleic acid detection technology, variation in detection rate from different manufacturers, disagreements in interlaboratory consultation caused by low patient viral load or improper clinical sampling [8,9]. In addition, nucleic acid detection cannot accurately determine the severity of disease in COVID-19 patients.

As a promising method recommended by the diagnosis and treatment program (7th trial edition) of National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China [10], high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) plays an essential role in the diagnosis and monitoring prognosis in COVID-19 patients. The main CT appearances of COVID-19 include ground glass opacities (GGOs) and patchy consolidations, which have respectively been regarded as a marker of early and progression stage of disease [11]. Based on the above-mentioned image abnormalities, HRCT could provide supplementary information to improve the planning of treatment, and evaluate the variations of image. To the best of our knowledge, little literature focuses on the change of CT appearances among different clinical types during the course of medical treatment. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the discrepancy of series CT manifestations in COVID-19 among different clinical types within the short-term follow-up periods, aiming to help clinicians monitor and predict outcome and to make more accurate and effective clinical decisions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

From January 22 to March 5, 2020, 7 consecutive COVID-19 patients from the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical Collage, one of the designated hospitals in Nanchong, Sichuan Province, were enrolled into our study. All patients tested positive for 2019-nCov in the laboratory testing of respiratory secretions obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage, endotracheal aspirate, nasopharyngeal swab, or oropharyngeal swab. The patients were subsequently subdivided into common, severe and critical groups based on clinical criteria [10]. The baseline data are recorded in Table 1 . All patients underwent an initial and at least 2 follow-up thoracic CT during the study period (total 24 studies). The interval between onset of disease and initial CT scanning was 3 days (range, 1–9 days), and the mean time between initial CT and first follow-up CT, and between first and second follow-up was 3 days (range, 2–4 days) and 2.5 days (range, 1–4 days), respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics in COVID-19 patients.

| Characteristics | Patient (n = 7) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 3 |

| Male | 4 |

| Age (y) | 53.86 ± 12.48 |

| Clinical type | |

| Common | 2 |

| Severe | 4 |

| Critical | 1 |

| Signs and symptoms | |

| Fever | 6 |

| Cough | 4 |

| Fatigue | 3 |

| Headache and dizziness | 1 |

| Dyspnea | 1 |

| Nausea | 2 |

| Asymptomatic | 1 |

| Exposure history | |

| Exposure to Wuhan | 2 |

| No exposure to Wuhan | 4 |

| Unknown exposure | 1 |

2.2. Image acquisition

All CT examinations were performed with a 128-row multidetector CT system (SOMATOM Definition Flash, Siemens Healthcare systems, Germany). Scanning coverage was from the thoracic inlet to the level of middle of the left kidney. The CT scanning protocol was as follows: tube voltage of 120 KV, tube current of 250 mA (automatic exposure control employed), rotation time of 0.35 s, pitch of 1.5 mm, detector collimation of 0.6 mm, slice thickness/reconstruction thickness of 5 mm/1 mm. All scans were performed in the supine position during end-inspiration. Data were transferred to the image processing workstation (SOMATOM Definition Flash, Siemens Healthcare systems, Germany).

2.3. Imaging analysis

All CT images were reviewed on the above-mentioned workstation at lung window (width of 1000 HU and window level of −700 HU). In order to ensure accuracy of analysis, all images were independently evaluated by an experienced radiologist (the first author with three years of experience in thoracic radiology), and an experienced radiological professor (the corresponding author with 12 years of experience in thoracic radiology) blinded to clinical information. In case of discrepancy between the 2 observations, final adjudication was made by a third radiologist (co-corresponding author with 22 years of experience in radiology).

According to expert consensus [11], the initial and follow-up CT abnormalities among groups were assessed mainly based on the following features: ① presence of ground-glass opacities (GGO) or consolidation; ② presence of other abnormalities (e.g. air-bronchogram, reticulation, interlobular septal thickening, and bronchiectasis); ③ lesion shape (e.g. patchy, nodular, etc.); Additional, we devised a semi-quantitative scoring system to evaluate the extent and progression of disease in order to assess the severity of the disease more accurately. As illustrated in Table 2, Table 3 , the CT lesion extent and density scores were determined based on the anatomic distribution and density of lung lesions with reference to the reported semi-quantitative score system [12,13]. The extent score was assessed according to the extent of lesion distributed on the five lung lobes, and the density score was evaluated based on the percentages of GGO and consolidation in each COVID-19 lesion. Thus, the score range for both lungs in each patient is from 0 (no detectable abnormality) to 20 (more than 75% of each lung lobe involved by COVID-19 lesion and 100% of consolidation in each lesion).

Table 2.

Scope scoring system of COVID-19 on computed tomography.

| Extent of lobe involved | Percentage (%) | Score |

|---|---|---|

| None | 0 | 0 |

| Minimal | 1–25 | 1 |

| Mild | 26–50 | 2 |

| Moderate | 51–75 | 3 |

| Severe | 76–100 | 4 |

Table 3.

Density scoring system of the COVID-19 on computed tomography.

| Category of lesions in a lobe based on the density | Score |

|---|---|

| No abnormal findings | 0 |

| Pure GGO | 1 |

| GGO with <50% consolidation and/or other abnormalities | 2 |

| GGO with ≥50% consolidation and/or other abnormalities | 3 |

| Consolidation with other abnormalities without GGO | 4 |

GGO, Ground glass opacity.

To assess the intra-observer variability of the above semi-quantitative measurements, the first author repeated the image data analysis three days later. The intra-observer variability was obtained through comparison of the two sets of measurements by the first author. The inter-observer variability was accessed by comparison of the respective measurements of the first and corresponding authors.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics software (version 25.0). Both intra-observer and inter-observer variability were tested for CT scores using the inter-class correlation coefficient (ICC). The semi-quantitative extent and density scores of COVID-19 lesions on initial CT were considered to be reproducible when the ICC was greater than 0.75 [14]. Statistical difference was defined as P < 0.05 for all tests.

3. Results

3.1. CT manifestations

On initial CT, the common type mainly appeared as single or scattered focal GGOs and nodules located in central lobule, separated by a grid-like thickening of interlobular septa which was dominant in the middle and lower pleura (Fig. 1 A). Severe patients had focal consolidation or patchy opacity in middle and lower lobules of bilateral pulmonary surrounded by GGOs (Fig. 2 A). In critical cases, meanwhile, HRCT showed multiple patchy consolidation surrounded by a wide range of GGO with air-bronchogram inside distributing bilateral lungs from hila regions to the whole lung fields (Fig. 3 A). In general, GGO was the main finding in common type whereas consolidation was the most common pattern observed in severe and critical cases, all abovementioned lesions were distributed in peripheral and subpleural areas of bilateral lung tissue.

Fig. 1.

Initial and follow-up HRCT in a common case. A 49-year old male, who was asymptomatic and had no exposure history to Wuhan City. A, Initial CT illustrated multiple patchy GGOs distributed mainly in the peripheral and posterior of the lungs. The CT scope and density score was 4 and 5, respectively. B, On first follow-up CT, the GGOs were in slighter density and smaller range, with the respective CT scope and density scores being 4 and 3. C, Second follow-up CT 7 days after admission demonstrated an improvement in absorption with fewer GGOs. Second follow-up CT extent and density scores were 2 and 2 respectively.

Fig. 2.

Initial and follow-up HRCT of severe case. A 55-year old female with fever and cough symptoms A, Initial CT showed bilateral GGOs and consolidations, with the extent and density score of 7 and 10, respectively. B, First follow-up CT illustrated decreasing size of consolidation surround by slight GGOs. The extent and density scores were 6 and 9 respectively. C, Second follow-up CT 8 days after admission showed previous opacifications being dissipated into irregular linear opacities. Respective second follow-up CT extent and density scores were 5 and 7.

Fig. 3.

Initial and follow-up HRCT of critical case. A 60-year old man with a history of long-term residence in Wuhan presented with fever and dyspnea, ultimately requiring intensive care unit admission. A, Initial CT showed multiple patchy consolidation surrounded by a wide range of GGO in bilateral pulmonary, initial CT scope and density scores were 19 and 12 respectively. B, First follow-up CT illustrated the density and the volume of consolidation were significantly increased. Respective first follow-up CT extent and density scores were 20 and 16. C, Second follow-up CT showed a progression with enlargement of GGOs, and increasing volume and attenuation of consolidation. Second follow-up CT extent and density scores were 20 and 19 respectively.

During follow up, most common and severe cases saw improvements in their lesions, manifested as the decreasing of GGO density, partial absorbing of consolidation and changing into strand-like opacity, reducing lesion volume, and the thickened interlobular septum returned to normal (Fig. 1B and C, Fig. 2B–C). However, aggravation of the lesion was noted in critical patients, as the consolidations and GGOs progressed to the increased density and enlargement volume (Fig. 3B and C).

3.2. Quantification of CT appearance

The mean intra-observer and inter-observer intraclass correlation coefficients were 0.92 (95% CI: 0.83–0.96) and 0.91 (95% CI: 0.81–0.96) for extent score, and 0.95 (95% CI: 0.88–0.98) and 0.92 (95% CI: 0.81–0.97) for density score, respectively. Therefore, the average of the extent score and density score from the two set of measurements was used for the subsequent statistical analysis.

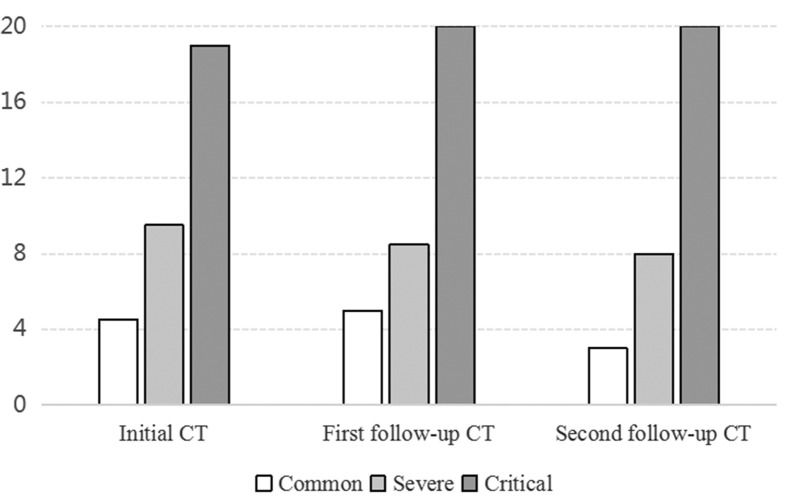

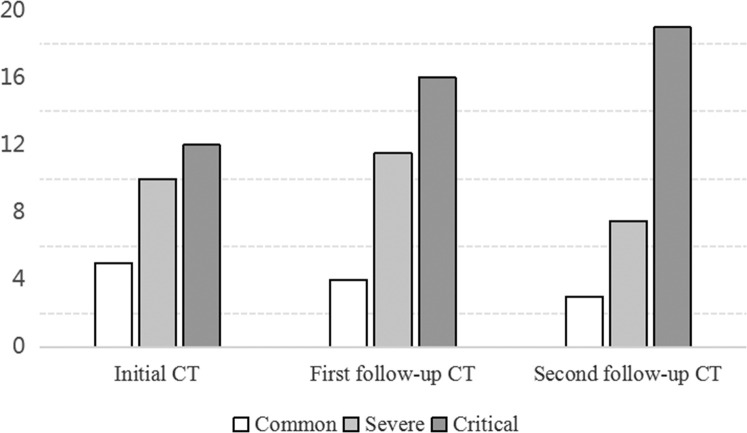

As shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5 , the scope and density score in common (4.5 and 5, respectively), severe (9.5 and 9.5, respectively) and critical (19 and 12, respectively) cases were increased, which was consistent with clinical manifestations. During follow-up, the extent and progression score in common and severe patients was significantly decreased. However, the scope score of critical case reached the highest point on follow-up CT, accompanied with gradually increased density score, indicated patient undergoing progressed disease course.

Fig. 4.

The extent scores among common, severe and critical cases. On initial CT, the critical type exhibited a greater scope score and showed slight elevation during follow-up CT scanning. In common and severe cases, the lesion extent significant decreased after treatment.

Fig. 5.

Density scores among common, severe and critical cases. On series CT scanning, critical/common cases had gradient increased/decreased density scores in series CT scanning. Severe cases reached the maximum density scores at the first follow-up while decreased significantly on second follow-up.

4. Discussion

The emergence and spread of COVID-19 have caused the large global outbreak to become a major public health issue [15]. As of March 13, 2020, 81,003 laboratory-confirmed cases were reported in 31 provinces in China [4]. Of these, 3181 were deaths which mainly progressed from severe and critical patients, and who tended to develop to serious complications including ARDS and multiple organ failures leading to insufficient curative efforts. Therefore, it is important to accurately assess the clinical type of patient and the effect of treatment for each type.

According to the guideline of diagnosis and treatment program on COVID-19 (trial version 7) issued by China's National Health Commission [10], patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 can be divided into common, severe and critical clinic types based on symptoms, laboratory examination and imaging. As one of the reference standards for clinical staging, the abnormal thoracic CT appearance could help in early diagnosis of disease and efficiently evaluate the extent and progress of COVID-19.

Our study found that the initial CT appearances vary according to the clinical type; this is consistent with previous reports [[16], [17], [18]]. The discrepancies of CT finding among different clinical types could be explained as the CT abnormalities might respectively reflect the potential pathological abnormalities in different stages of the disease. Seen mainly in the early and decaying stages of the disease, GGOs might be associated with the pathological small amount of exudation of fluid in alveolar cavity and interlobular interstitial edema [19]. As a marker of more severe phase, consolidation could reflect the pathological features of a large amount of cell-rich or fibrous exudation accumulated in the alveolar cavity and pulmonary interstitium [20]. Additionally, the extent of GGO and consolidation in severe and critical were greater than that of common cases. Similarly, severe and critical cases tend to have higher extent and density scores compared with common type patients by semi-quantitative score system. Therefore, CT findings could accurately evaluate the severity of disease with different clinical types, and provide evidence for the further management.

Moreover, CT could also monitor lesion status among different clinical types of COVID-19 during the same treatment periods. We found that the variation of extent and progression obtained on the follow-up CT could exist among patients with different clinical conditions. In detail, the improvement of disease could be observed in common and severe type, exhibited as total or partial resolution of GGO or consolidation, result in decreasing of scope and density scores. These changes may relate to the underlying pathological features of fibrous exudation of the alveolar cavity and the disappearance of capillary congestion in the alveolar wall, which may represent a dissipation phase of COVID-19 pneumonia [[21], [22], [23]]. In contrast, critical case could progress to the more severe phase of disease during the same period of follow-up CT, represented by enlargement of GGOs, and increasing volume and attenuation of consolidation [[24], [25], [26]]. Numerous GGOs might be associated with the invasion of adjacent lung tissues and spread in lung [20]. As the pathologic feature mainly including infiltration of alveolar by inflammatory cells and deposition of exudation in the airway wall accompanied by destroyed and incomplete alveolar structures, change in consolidation could indicate the continuous progress of the disease, which has been reported by previously studies [27,28].

This study had several limitations. Firstly, the sample size was very small especially in the critical type. A larger sample size of COVID-19 patients is thus required for further investigation to compared imaging feature among different groups of different clinical types. Secondly, the semi-quantitative scoring system of disease severity in our study was based on the typical CT manifestations applied in the expert consensus [11], other abnormal findings such as reticulation and interlobular septal thickening were not particularly evaluated, further modification is required. Finally, the follow up CT had a short time interval, it would be still inconclusive with CT follow up findings to evaluate treatment efficacy.

In conclusion, the initial and short-term follow-up chest CT findings of COVID-19 pneumonia vary according to the clinical type. The common and severe types tend to have relatively less severe disease courses which improve after treatment while the CT manifestations were serious in critical patient, and the condition had aggravated during follow-up. CT scanning could accurately assess the severity of COVID-19 pneumonia, and help to monitor diseases transformation during follow-up among different clinical condition.

Ethic statement

The Ethic Committee in our hospital approved this research (approval number, 2020ER007-1). All enrolled subjects agreed to participate in this research and written informed consent was obtained from the enrolled subjects prior to investigation.

Funding

This study was supported by the Nanchong City-Level Science and Technology Plan Project for the Novel Coronavirus Epidemic Prevention and Control Category (Grant No. 20YFZJ0103) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.81801674).

Authors' contributions

Yuting Jiang contributed to data analysis and interpretation, performed statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Dandan Guo carried out data acquisition, and performed data analysis and interpretation. Chunping Li contributed to study design as well as the preparation, editing and review of the manuscript. Tianwu Chen participated in the study design, data analysis and interpretation. Rui Li participated in the study design, contributed to quality control of data and algorithms, and editing and review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Beijing You'an Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University.

References

- 1.WHO. Novel coronaviruses (COVID-2019) situation report 1. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) and the virus that causes it. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. WHO Director-General's remarks at the media briefing on 2019-CoV on 11 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health Emergency Office of National Health Commission of the PRC . 2020-03-13. Update on the epidemic of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia as at 24:00 on 13 March. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassetti M., Vena A., Giacobbe D.R. The novel Chinese coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections: challenges for fighting the storm. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;50(3) doi: 10.1111/eci.13209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renshaw A.A., Gould E.W. Reducing false-negative and false-positive diagnoses in anatomic pathology consultation material. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137(12):1770–1773. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0012-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu X., Chen P., Wang J., Feng J., Zhou H., Li X. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63(3):457–460. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China . 2020. Diagnosis and treatment scheme for coronavirus disease 2019 (Trial Version 7). 3.5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chinese Society of Radiology Radiological diagnosis of new coronavirus infected pneumonitis: expert recommendation from the Chinese Society of Radiology (First edition) Chin J Radiol. 2020;54:E001-E001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie X., Zhong Z., Zhao W., Zheng C., Wang F., Liu J. Chest CT for typical 2019-nCoV pneumonia: relationship to negative RT-PCR testing. Radiology. 2020:200343. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung M., Bernheim A., Mei X., Zhang N., Huang M., Zeng X. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020;295(1):202–207. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shrout P.E., Fleiss J.L. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hui D.S., Azhar I.E., Madani T.A., Ntoumi F., Kock R., Dar O. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health-the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y., Xia L. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): role of chest CT in diagnosis and management. Am J Roentgenol. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiong Y., Sun D., Liu Y., Fan Y., Zhao L., Li X. Clinical and high-resolution CT features of the COVID-19 infection: comparison of the initial and follow-up changes. Invest Radiol. 2020;55(6):332–339. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei J., Li J., Li X., Qi X. CT imaging of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295(1):18. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholls J., Poon L., Lee K., Ng W., Lai S., Leung C. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1773–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin Y., Cai L., Cheng Z., Cheng H., Deng T., Fan Y. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan J., Yuan S., Kok K., To K., Chu H., Yang J. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X., Chen P., Wang J., Feng J., Zhou H., Li X. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63(3):457–460. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang D., Lin M., Wei L., Xie L., Zhu G., Dela Cruz C.S. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus infections involving 13 patients outside Wuhan, China. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323(11):1092–1093. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin C., Ding Y., Xie B., Sun Z., Li X., Chen Z. Asymptomatic novel coronavirus pneumonia patient outside Wuhan: the value of CT images in the course of the disease. Clin Imag. 2020;63:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ooi G., Khong P., Müller N., Yiu W., Zhou L., Ho J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: temporal lung changes at thin-section CT in 30 patients. Radiology. 2004;230(3):836–844. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303030853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song F., Shi N., Shan F., Zhang Z., Shen J., Lu H. Emerging coronavirus 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295(1):210–217. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong K., Antonio G., Hui D., Lee N., Yuen E., Wu A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: radiographic appearances and pattern of progression in 138 patients. Radiology. 2003;228(2):401–406. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2282030593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]