Abstract

Since November 2018, Blood Advances has published American Society of Hematology (ASH) clinical practice guidelines on venous thromboembolism, immune thrombocytopenia, and sickle cell disease. More ASH guidelines on these and other topics are forthcoming. These guidelines have been developed using consistent processes, methods, terminology, and presentation formats. In this article, we describe how patients, clinicians, policymakers, researchers, and others may use ASH guidelines and the many related derivates by describing how to interpret information and how to apply it to clinical decision-making. Also, by exploring how these documents are developed, we aim to clarify their limitations and possible inappropriate usage.

Introduction

Since November 2018, Blood Advances has published American Society of Hematology (ASH) clinical practice guidelines on venous thromboembolism (VTE),1-8 immune thrombocytopenia,9 and sickle cell disease.10-12 More ASH guidelines on these and other topics are forthcoming. In this article, we describe why ASH guidelines are trustworthy, and how patients, clinicians, policymakers, researchers, and others may use them. Specifically, we describe where to find relevant information and provide guidance on how to interpret recommendations, and how to apply them to clinical decision-making.

These ASH guidelines have been developed using consistent processes, methods, terminology, and presentation formats that meet current guideline-development quality standards. These standards have been developed by key organizations like the Institute of Medicine (now integrated into the National Academy of Sciences), the Guideline International Network (GIN), the World Health Organization, and a few other influential organizations.13-18

We begin this article by defining what constitutes a trustworthy guideline and how ASH guidelines adhere to this standard. We then address the organization of ASH guidelines in 3 main sections: (1) “Making sense of the recommendations” explains how recommendations are presented, how they should be interpreted, and what they are based on; (2) “Making sense of the evidence and the judgments behind the recommendations” explains how supporting evidence is summarized quantitatively and qualitatively using an accepted methodological approach; and (3) “Using the guidelines” describes the ASH tools to support optimal use of the recommendations in clinical and other contexts.

What is a guideline?

Guidelines for clinical decision-making have been developed and promulgated by individuals, public health institutions, for-profit businesses such as insurance companies, and nonprofit organizations, including medical specialty societies such as ASH, for decades. Throughout this time, guidelines, in general, have been rightly criticized as untrustworthy or not useful because they are not based on best available evidence, offer vague advice, or reflect the values of the guideline developer rather than the values of patients. Furthermore, many organizations have labeled their guidelines as either evidence-, expert-, or consensus-based. This categorization is both misguided and misleading, as all 3 of these components are integral to guideline development. Truly evidence-based recommendation development requires evidence appraisal and interpretation, expert opinion (which is an interpretation of evidence and differs from expert evidence), and consensus building.19,20

The Institute of Medicine (IOM; now called the Health and Medicine Division [HMD] of the National Academy of Medicine) provides a suitable definition of clinical practice guidelines, describing them as “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.”14(p4) Core criteria for trustworthy guidelines include that they13,14,16,18,21-23:

be developed by a knowledgeable, multidisciplinary panel of experts and representatives from key affected groups;

be based on a systematic review of the existing evidence;

consider important patient subgroups and patient preferences as appropriate;

be developed through an explicit and transparent process that minimizes distortions, biases, and conflicts of interest24;

provide a clear explanation of the logical relationships between alternative care options and health outcomes, and provide ratings of both the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations25-28; and

be reconsidered and revised as appropriate when important new evidence warrants modifications of recommendations.

The current ASH guideline-development process adheres to the IOM’s criteria for trustworthy guidelines and can be summarized as follows:

ASH guideline panels are created to be diverse and balanced with respect to disease and methodological expertise, represent multiple perspectives, and include varied stakeholders including patient representatives.

The guideline-development process is wholly funded through the general operating budget of ASH or, for some guidelines, by ASH with collaborating nonprofit organizations. Direct funding from for-profit entities that could be affected by the guidelines is not accepted. Conflicts of interest of all participants in the development process are managed through panel composition, disclosure, and recusal from panel deliberations/voting.

The panel prioritizes clinical questions that drive decision-making and that specify the population, intervention(s), comparison(s), and patient-focused outcomes.

A research team systematically identifies and synthesizes the best available evidence, including evidence on baseline risks of a disease, health effects of interventions, patient values, resource utilization, impacts on health equity, and barriers to and facilitators of implementation.

The guideline panel uses the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to interpret the evidence and form recommendations using the GRADE Evidence-to-Decision (EtD) framework, which makes explicit all judgments about evidence and the rationale for a recommendation29,30 (some guidelines developed by ASH in collaboration with other organizations or endorsed by ASH have not used GRADE).

The draft recommendations and EtD frameworks are made available for external review by all stakeholders, including the general public.

The guidelines undergo peer review and are published along with the supporting evidence and EtD frameworks for each recommendation.

This formal approach reduces the risk of bias from unmanaged conflicts of interest and makes the underlying evidence, assumptions, values, and judgments transparent and trustworthy for end users, including clinicians and patients.

What is the purpose of guidelines?

The ASH guideline-development process aims to produce recommendations that assist clinicians and patients in making decisions about diagnostic and treatment alternatives. Recommendations may be particularly helpful when there is limited evidence, uncertainty about the effects of the interventions, controversy, or variation in practice. Other purposes of ASH guidelines are to inform policy, education, advocacy, and future research needs.

What is a guideline not for?

Despite their best intentions, users may misinterpret and thereby unintentionally misuse guidelines to narrowly define reimbursement, physician negligence, or malpractice. For example, there is often no clearly superior intervention for a clinical problem, thus patients and clinicians must weigh the desirable and undesirable consequences of management alternatives to arrive at a final decision. In such circumstances, guideline panels will still suggest a course of action, acknowledging that different decisions may be appropriate according to the circumstances. This is represented by a conditional (or “weak”) recommendation in the current guideline-development paradigm. If a conditional recommendation is used by payors to deny coverage of the disfavored alternative, this is clearly a misinterpretation of the panel recommendation, and potentially harmful. A more appropriate interpretation of a conditional recommendation by payors is a mechanism that captures shared or informed decision-making in situations in which the balance of desirable and undesirable consequences does not allow clear-cut conclusions.

A similar problem can arise if recommendations are used in legal context to establish a “standard of care.” Although guideline recommendations can be considered in the process of analyzing the appropriateness of health care providers’ actions, this should not occur in the absence of context. Guideline recommendations, whether strong or conditional, are not intended to dictate a rigid standard of practice. As emphasized herein, they should be used to inform decisions that depend on the patient’s unique circumstances and preferences. When viewed in this way, it is clear that for an individual patient, the best course of action may be opposite to what was recommended by the guideline, especially when recommendations are conditional.

Accurately defining the appropriateness of health care–related decisions is complex. Despite the mentioned limitations of using evidence-based recommendations to this end, well-developed strong recommendations are probably the best alternative available as they represent situations in which moderate or high certainty exists in which all or almost all patients will benefit from a certain course of action. Policymakers can develop quality and performance indicators using strong recommendations but should avoid using conditional recommendations for that purpose.

In an effort to address potential misuse of the guidelines, a section entitled “How to Use these Guidelines” is included with all recently published ASH guidelines. It cautions that “these guidelines are not intended to serve or be construed as a standard of care,” and that following the guidelines cannot guarantee a successful clinical outcome.

Finally, ASH guidelines will never address all of the potential questions pertaining to the diseases or conditions being discussed. Recommendation development requires careful consideration and deliberation; ASH prioritizes the conditions and clinical questions, perceived to be relevant by the clinical community and patients, that can be clearly answered by recommendations. For users needing more and other types of information (eg, how does a medication work), other sources of information should be used, including textbooks and reports of original research.

How is an ASH guideline organized?

Following the development process, ASH guidelines are published as a journal article, using standard organization and preferred language as well as online material. The article is authored by the guideline panel and members of the systematic review team and undergoes blind peer review. As the official, citable record of the guidelines, the published guideline documents describe in detail the development process and methods, the results of the process (ie, recommendations), and supporting evidence. Box 1 describes the main components of the article.

Box 1. Components of published ASH guidelines

Background sections

Aims

Description of the health problem(s)

Description of the target populations

Methods

Guideline questions

Recommendations

Recommendation statements

Remarks

Summary of evidence

Discussion of health benefits, harms, and other factors considered by the guideline panel when forming each recommendation

Research needs

Conclusions

Limitations

What other guidelines are saying and what is new in these guidelines

Revision or adaptation of the guidelines

Supplements

Guideline panel membership

Disclosure-of-interest forms

GRADE EtD frameworks

GRADE evidence profiles

The article may also include official correspondence, corrections, or updates.

Complete documentation of the process and guidelines results in a lengthy document. Furthermore, some ASH guideline topics (eg, VTE, sickle cell disease) have been addressed by multiple guideline panels, each addressing a different aspect of the disease; these guidelines are published as multiple articles. Electronic versions facilitate online navigation and links across guidelines. Many users, especially in clinical contexts, may prefer accessing ASH guidelines through other tools such as the ASH guidelines app or pocket guides (see “Using the guidelines”).

Making sense of the recommendations

What is GRADE?

GRADE is a methodology used by over 100 health guideline developers summarizing the best available evidence, assessing its certainty (also known as quality), and moving from evidence to recommendations. GRADE has evolved over 2 decades and provides rigor, transparency, and consistency across all ASH guidelines.26,28,31,32 More information is available in the GRADE Handbook in the official GRADEpro app (www.gradepro.org) and in peer-reviewed publications.

Anatomy of a recommendation

For many users, the most important contents of ASH guidelines are the recommendations. Consistent with the GRADE approach, ASH guideline recommendations follow a structure and preferred language that is intended to be unambiguous with respect to:

whom the recommendation is for,

what is recommended and against what alternative,

the strength of the recommendation,

the certainty in evidence that supports the intervention effects,

complementary guidance included as remarks, and

who is making the recommendation

Example recommendations from ASH guidelines are presented in Box 2.

Box 2.

Example recommendation 1

For pregnant women with proven acute superficial vein thrombosis, the ASH guideline panel suggests using LMWH over not using any anticoagulant (conditional recommendation based on low certainty in the evidence of effects ⊕⊕◯◯).1

Example recommendation 2

For pregnant women with acute VTE, the ASH guideline panel recommends antithrombotic therapy compared with no antithrombotic therapy (strong recommendation based on high certainty in the evidence about effects ⊕⊕⊕⊕).1

Example recommendation 3

The ASH guideline panel recommends against using a positive D-dimer alone to diagnose PE (strong recommendation based on high certainty in the evidence of effects on clinical outcomes ⊕⊕⊕⊕ and moderate certainty in the evidence of diagnostic accuracy studies ⊕⊕⊕◯).3

Example recommendation 4

In adults with newly diagnosed immune thrombocytopenia, the ASH guideline panel suggests either prednisone (0.5-2.0 mg/kg per day) or dexamethasone (40 mg/d for 4 days) as the type of corticosteroid for initial therapy (conditional recommendation based on very low certainty in the evidence of effects ⊕◯◯◯).9

Remarks: If a high value is placed on rapidity of platelet count response over concerns for potential side effects of dexamethasone, then an initial course of dexamethasone over prednisone may be preferred.

Example recommendation 5

The ASH guideline panel suggests using a strategy starting with CTPA for assessing patients suspected of having PE in a population with high prevalence/pretest probability (≥50%) (conditional recommendation for CTPA based on very low certainty in the evidence of effects on clinical outcomes ⊕◯◯◯and moderate certainty in the evidence of diagnostic accuracy studies ⊕⊕⊕◯).

Remarks: Validated clinical decision rules were used to assess clinical probability of PE in studies evaluating different diagnostic strategies for patients suspected of having a first-episode PE. The Geneva score has been validated only in an outpatient population. If a 2-level clinical decision rule is used, this recommendation corresponds to the “likely PE” category.3

Example recommendation 6

For children and adults with sickle cell disease (SCD) and albuminuria, the ASH guideline panel suggests the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) (conditional recommendation based on low certainty in the evidence about effects ⊕⊕◯◯).12

Remarks: (1) The initiation of ACEi and ARB for patients with SCD requires adequate follow-up and monitoring of side effects (eg, hyperkalemia, cough, hypotension).

Whom is the recommendation for?

When making sense of a recommendation, primary attention and importance may be given to the patient population to whom the recommendation applies. Sometimes, the target population of a specific recommendation may be broad (eg, a recommendation for all individuals with VTE). Other recommendations may apply to a very specific population (eg, a recommendation about the use of thrombolysis in pregnant women with pulmonary embolism [PE] and hemodynamic failure).

Even within the intended population, there will be individuals with different characteristics that may have baseline risks for important health outcomes substantially different than the population average. For example, clinicians applying Example recommendation 1 in Box 2 for an individual patient may need to consider that among pregnant women with superficial vein thrombosis, some may have lower risk for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or PE (eg, patients with more distal superficial vein thrombosis). Remarks and discussion within ASH guidelines may help clinicians interpret and individualize the recommendations for specified populations (see “Complementary guidance included as remarks”); tools and strategies are also discussed in “Using the guidelines.” For example, in Example recommendation 1 in Box 2, the following statement was added to the recommendation’s justification, “The guideline panel determined that there is a low certainty of evidence for a net health benefit from using anticoagulant interventions for acute superficial vein thrombosis. For more distal or less symptomatic superficial vein thrombosis and for patients who are needle averse, the benefits of intervening may be less.”

What is recommended and against what alternative?

Every recommendation compares at least 2 options. The “direction” of the recommendation refers to which option is favored over the other. In Example recommendation 2 in Box 2, guideline users should interpret the direction as in favor of antithrombotic therapy, whereas Example recommendation 3 in Box 2 should be interpreted as against using D-dimer alone to diagnose PE.

Sometimes, a guideline panel cannot decide whether 1 of 2 active options is superior and the panel may suggest either option. Although recommendations like this may be considered as less useful, they are appropriate when the desirable and undesirable consequences of different active interventions are judged by the panel to be evenly balanced (Example recommendation 4 in Box 2).

Clear and actionable recommendations require both a description of the intervention that is being recommended as well as the intervention(s) with which it is compared. In most instances, both are mentioned in the recommendation statement (see Example recommendations 1, 2, and 4 in Box 2). Sometimes obvious comparators might be omitted to improve the readability of a recommendation (see Example recommendations 3, 5, and 6 in Box 2).

What is the certainty in evidence supporting the recommendation?

Every recommendation includes a statement about the certainty in the body of the evidence that supports that recommendation (certainty about the effect on health benefits and harms or in the test accuracy of the intervention being considered).

The certainty in the evidence expresses the results of a structured judgment about how confident the panel is in the effect estimates that inform a particular recommendation. In ASH guidelines, the certainty in the evidence is categorized according to GRADE as high, moderate, low, or very low. A high or moderate overall certainty in the evidence indicates that we can be confident in our knowledge on the effects of interventions. To reach this level of certainty, typically, the body of evidence needs to be grounded in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) without other reasons for concern (see “Criteria that determine the strength of a recommendation”), or be based on well-done nonrandomized studies with very large effects. In contrast, low- or very low–certainty evidence reflects important uncertainty regarding the effects of an intervention; guideline panelists must decide on the best course of action acknowledging that important evidence gaps exist.

The certainty in the evidence is determined for each relevant outcome for the whole body of evidence by a systematic assessment of the potential limitations in the study design and execution (risk of bias), inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias (see “Criteria that determine the strength of a recommendation”). For the certainty in the evidence of the intervention on health effects, the process involves a first step in which the certainty is assessed individually for every relevant outcome, and a second step in which the overall certainty across health outcomes is determined. For the latter, typically, the lowest certainty rating of the individual critical outcomes is adopted as the overall certainty associated with a recommendation.

For questions about the use of tests (for example, diagnostic recommendations), judgments about the certainty in the evidence are based on the same concepts.33-37 However, information about the direct effects of diagnostic interventions on patient-important outcomes is seldom available. Hence, panels sometimes only label the certainty in the evidence for a test’s diagnostic accuracy (eg, true positives, true negatives, etc), which is a core component of such a recommendation but does not always consider the impact of the test on patient outcomes.34 In the ASH guidelines that address diagnostic tests or strategies, patient-important outcomes have been considered directly (when evidence was available) or indirectly by modeling on diagnostic accuracy information, that is, by modeling the expected clinical consequences of true-positive, true-negative, false-positive, and false-negative results of a diagnostic test or pathway. Consider, for instance, the situation in which different diagnostic strategies are compared for patients suspected of having a PE in the context of high prevalence/pretest probability (>50%) (Example recommendation 5 in Box 2). For the described scenario, the effects of different diagnostic strategies on clinical outcomes such as recurrent VTE, major bleeding, and mortality are unknown (very low certainty in the evidence). Therefore, the panel relied on evidence on the diagnostic accuracy of various strategies (moderate certainty) to suggest a diagnostic strategy starting with computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) over other alternatives. To reach this conclusion, the panel considered desirable effects as increasing the number of patients with true-positive and true-negative test results (ie, patients accurately diagnosed and treated) and undesirable effects as increasing the number of patients with false-positive and false-negative test results, which would lead to receiving unnecessary anticoagulation or morbidity/mortality from missed diagnosis. They also accounted for radiation exposure and other factors in making their recommendations (https://guidelines.gradepro.org/profile/6affa6fc-0c1c-44e0-a901-2558ee36032b).

Furthermore, it is evident that for other EtD criteria (eg, cost, values, and preferences), evidence also comes with various levels of certainty. For many ASH guidelines, this certainty was assessed, and it may have influenced recommendations, but the certainty in the evidence for these criteria is typically not labeled in the recommendation. Instead, the grading reflects the certainty in estimates of the health effects of the intervention and comparison.

What is the strength of the recommendation, and how should this be interpreted?

The strength of a recommendation reflects the extent to which the guideline panel is confident that the desirable consequences of an intervention outweigh the undesirable consequences. Desirable consequences of an intervention include benefits on health-related outcomes such as reduction in mortality and morbidity, improvement in quality of life, and reduction in the burden of treatment (such as having to take drugs or the inconvenience of blood tests). Undesirable consequences include adverse effects on health outcomes like a deleterious impact on morbidity, mortality, or quality of life, and increased use of resources.29,30 A strong recommendation reflects the conviction of the panel that the desirable consequences of an intervention clearly outweigh its undesirable consequences. A conditional recommendation, in contrast, expresses that the balance between the desirable and undesirable consequences is close or uncertain.

In the ASH guidelines, strong recommendations are framed as “the ASH guideline panel recommends...,” whereas conditional recommendations are expressed as “the ASH guideline panel suggests…” Table 1 offers interpretation of strong and conditional recommendations from different perspectives.5

Table 1.

Interpreting strong and conditional recommendations from different perspectives

| Implications for | Strong recommendation | Conditional recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Most individuals in this situation would want the recommended course of action, and only a small proportion would not. | The majority of individuals in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but many would not. Decision aids may be useful in helping patients to make decisions consistent with their individual risks, values, and preferences. |

| Clinicians | Most individuals should follow the recommended course of action. Formal decision aids are not likely to be needed to help individual patients make decisions consistent with their values and preferences. | Different choices will be appropriate for individual patients, and clinicians must help each patient arrive at a management decision consistent with the patient’s values and preferences. Decision aids may be useful in helping individual risks, values, and preferences. |

| Policy makers | The recommendation can be adopted as policy in most situations. Adherence to this recommendation according to the guideline could be used as a quality criterion or performance indicator. | Policy-making will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders. Performance measures should assess whether decision-making is appropriate. |

| Researchers | The recommendation is supported by credible research or other convincing judgments that make additional research unlikely to alter the recommendation. On occasion, a strong recommendation is based on low or very low certainty in the evidence. In such instances, further research may provide important information that alters the recommendations. | The recommendation is likely to be strengthened (for future updates or adaptation) by additional research. An evaluation of the conditions and criteria (and the related judgments, research evidence, and additional considerations) that determined the conditional (rather than strong) recommendation will help to identify possible research gaps. |

Schünemann et al.5

Criteria that determine the strength of a recommendation

The GRADE approach is followed to determine the strength of the recommendations included in the ASH guidelines (see GRADE handbook for further details: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html). To this aim, a guideline panel needs to account for the relevant criteria for every recommendation. The key criteria are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Criteria that influence the strength and direction in the GRADE EtD frameworks

| Criteria | How the criterion influences the direction and strength of a recommendation |

|---|---|

| 1. Problem | The judgment about the problem is determined by the importance and frequency of the health care issue that is addressed (burden of disease, prevalence, cost, or baseline risk). If the problem is of great importance an intervention is more likely to exert large effects and a strong recommendation may be more likely. However, this is a guiding principle and not universally applicable to all recommendations. |

| 2. Values and preferences or the importance of outcomes | This describes how important health outcomes are to those affected, how variable they are, and whether there is uncertainty about this. |

| 3. Certainty in the evidence about the health benefits and harm | The higher the certainty in the evidence, the more likely is a strong recommendation. |

| 4. Health benefits and harms and burden and their balance | This requires an evaluation of the absolute effects of both the benefits and harms and their importance including the judgment about criterion 2. The greater the net benefit or net harm, the more likely is a strong recommendation for or against the option. |

| 5. Resource implications | This describes how resource intense an option is, if it is cost-effective and if there is incremental benefit. The more advantageous or clearly disadvantageous these resource implications are, the more likely is a strong recommendation. |

| 6. Equity | The greater the likelihood to reduce inequities or increase equity and the more accessible an option is, the more likely is a strong recommendation. |

| 7. Acceptability | The greater the acceptability of an option to all or most stakeholders, the more likely is a strong recommendation. |

| 8. Feasibility | The greater the acceptability of an option to all or most stakeholders, the more likely is a strong recommendation. |

Balance between desirable and undesirable effects.

The first key determinant of the strength of a recommendation is the balance between the desirable and undesirable health effects of the alternative management strategies, on the basis of the best estimates of those consequences. Consider, for instance, the use of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis, with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin (UFH), for critically ill patients. Administration of LMWH or UFH in this context probably reduces mortality, PE, and DVT with minimal increase in the risk of bleeding, and negligible inconvenience and costs. Advantages of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis outweigh the disadvantages, indicating the appropriateness of a strong recommendation (https://guidelines.gradepro.org/profile/783DCF1B-50FC-72D0-A1E1-3C31011E9471). When advantages and disadvantages are closely balanced, a conditional recommendation will become more likely. Consider, for instance, the use of thrombolytic therapy compared with anticoagulation alone in pregnant women with acute lower-extremity DVT. Thrombolytics may reduce the risk of severe postthrombotic syndrome at the expense of a significant increase in the risk of major bleeding. The close balance between benefits and harms in this scenario warrants a conditional recommendation (https://guidelines.gradepro.org/profile/76DD6628-F96A-93C7-AB00-87B3AA8A4BA2). This balance is determined by issues around baseline risk and the relative effects of an intervention that together are summarized as absolute effects.

Certainty in the evidence.

The second determinant of the strength of a recommendation is the certainty in the evidence in the effect estimates. If we are uncertain about the magnitude of the desirable and undesirable health effects of an intervention, making a strong recommendation for or against a particular course of action becomes problematic.38-41 The certainty in the evidence is evaluated on an outcome-per-outcome basis (ie, there might be high certainty in the intervention’s effects on VTE risk but low certainty in the effects on bleeding outcomes). Considering all of the certainty judgments on individual outcomes, the guideline panel decides on the overall certainty in the evidence, which determines how confident they are in the effects of the intervention in general. This judgment is usually driven by the lowest of the certainty judgments of the individual outcomes.

For instance, thromboprophylaxis with LMWH has an apparent benefit in reducing symptomatic PE, symptomatic DVT, major bleeding, and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, compared with UFH, in acutely ill medical patients.5 The randomized trials from which the effect estimates came were, however, judged at serious risk of bias due to an unclear random-sequence-generation process and absence of blinding, and provided imprecise estimates. For both of these reasons, the body of evidence was rated down as low certainty (https://dbep.gradepro.org/profile/FA048403-345D-A41B-8147-6657D26C1399). In this scenario, use of LMWH over UFH warrants a conditional recommendation.

Values and the relative importance of the outcomes.

The third determinant of the strength of a recommendation is uncertainty about, or variability in, the relative importance patients assign to the outcomes.42,43 Given that alternative management strategies will always have advantages and disadvantages, how a guideline panel values benefits, risks, and inconvenience is critical to the strength of any recommendation. If significant variability in patients’ values is known or assumed, it is expected that patients’ preferences for 1 treatment option over another will also vary; hence a strong recommendation would be inappropriate. Consider for instance the situation in which a patient with sickle cell disease presents with advanced chronic kidney disease. The options in this scenario include referring or not referring for renal transplant. Based on low-certainty evidence, the panel considered that the balance between benefits vs harms probably favors renal transplant. However, the panel acknowledged that there may be important uncertainty or variability in how much people value the primary outcomes based on different opinions about the risks of surgery and long-term immunosuppression. A strong recommendation would be inappropriate both because of the low certainty in the evidence and because of the potential variability in patients’ values and preferences.12

Cost.

Cost is another determinant of the strength of a recommendation. Cost is much more variable over time and geographical area than other outcomes. Drug costs tend to drop when patents expire, and charges for the same drug differ widely across jurisdictions. In addition, resource implications vary widely. For instance, a year’s prescription of the same expensive drug may pay for a single nurse’s salary in the United States and 30 nurses’ salaries in Peru. Thus, although higher costs reduce the likelihood of a strong recommendation in favor of an intervention, the context of the recommendation will be critical. In considering resource allocation, guideline panels must therefore be specific about the setting to which a recommendation applies. ASH guidelines are generally focused on well-resourced settings; however, efforts to adapt guidelines to lower-resource settings are pursued when these considerations become more context dependent (see “ASH VTE guideline adaptations”).

Although the strength and direction of recommendations are mainly driven by the criteria described herein, other relevant aspects should be taken into account (Table 2). Consider, for example, a conditional recommendation for a longer (6-12 week) international normalized ratio (INR) recall interval over a shorter (4-week) INR recall interval, during periods of stable INR control, for patients taking a vitamin K antagonist. In constructing this recommendation, the panel considered that longer INR intervals would increase health equity (especially for those with transportation barriers) and reduce the burden of treatment, which might improve acceptability (https://guidelines.gradepro.org/profile/87B38659-8876-FBC5-97CC-195E03A1F1FE).6

Complementary guidance included as remarks

In situations in which the panel considers that further guidance is necessary to ensure the proper understanding or implementation of a recommendation, additional statements to accompany the recommendation are included as remarks. For instance, in Example recommendation 6, Box 2, the ASH guideline panel recommended angiotensin inhibition for patients with sickle cell disease and albuminuria. However, the panel considered that further clarification was necessary, so they added a remark that adequate follow-up and monitoring of side effects is necessary. The inclusion of remarks varies across ASH guidelines, as some recommendations are more complex than others. ASH guidelines explicitly use nondirective language in remarks to avoid introducing statements that may be misunderstood as additional informal recommendations.

Who is making the recommendation?

The ASH guideline-development process includes multiple participants who have different roles and responsibilities, including ASH oversight committees, ASH staff, systematic review and evidence synthesis teams, manuscript authors and editors, and, at the center of the process, the guideline panel. Guideline titles include “American Society of Hematology” because the society sponsors the work and defines the process. However, recommendations are phrased as “the ASH guideline panel recommends (or suggests)” and should be understood to represent the judgment of the voting members of the guideline panel only. Guideline panel members represent varied experts in clinical content as well as methodologists and patient representatives. Recommendations may not constitute the opinion of some of the voting or nonvoting panelists (eg, panelists recused for conflicts of interest), ASH leadership, or ASH members at large.44 Because guidelines typically address challenging or controversial questions, different panels composed of different individuals could draw different conclusions and issue different recommendations. Guideline users should keep this in mind, particularly when interpreting and using recommendations based on low-certainty evidence. The benefit of the approach we describe here is that when different guideline panels consistently and transparently use the EtD framework, it is clear how they arrived at their decisions.23,45

Other guidance in the guidelines: good practice statements

In accordance with recommendations of the GRADE Working Group,46 good practice statements represent recommendations that ASH guideline panels agree are necessary and important for clinical care, but are not based on a systematic review of available evidence. These statements typically address “common-sense practices.”

Ideally, all prioritized questions should be answered following a full evidence assessment. However, in some situations this may represent an enormous amount of work with small chances of obtaining relevant information, when the answer seems clear. In these instances, the guideline-development team may decide to proceed with a good practice statement if all of the following conditions are met46:

the statement is clear and actionable;

the message is really necessary in regard to actual health care practice;

after consideration of all relevant outcomes and potential downstream consequences, including equity, implementing the good practice statement will result in large net-positive consequences;

collecting and summarizing the evidence would be a poor use of a guideline panel’s limited time and energy (opportunity cost is large); and

there is a well-documented clear and explicit rationale connecting the indirect evidence.

For instance, in a patient with immune thrombocytopenia in whom splenectomy is indicated, the ASH guideline panel decided to issue a good practice statement in favor of usual immunization practice prior to surgery.9 The statement is clear, actionable, and necessary, as the benefits of immunization in the context of splenectomy are universally accepted because of the risk of overwhelming postsplenectomy infection and the favorable safety profile of the recommended vaccines.

Because good practice statements are not based on systematic reviews of evidence and are not developed using a structured process, they should be used with more caution than graded recommendations.

Making sense of the evidence and the judgments behind the recommendations

Finding background information

As described in Box 1, published ASH guidelines include as supplemental files substantial documentation of the evidence and judgments behind every recommendation. These supplemental files provide useful information for guideline users seeking to better understand the recommendations.

Disclosure-of-interest forms.

A recommendation may be more or less credible depending on who made the recommendation, including what their conflicts of interest were and how these conflicts were managed. Under ASH policy, individuals with conflicts are allowed to participate in guideline development if they offer crucial expertise, but allowed conflicts are managed through disclosure, panel composition, and recusal.

On appointment to an ASH guideline panel, all individuals complete a disclosure form describing their financial interests and relationships as well as nonfinancial interests relevant to the guideline topic. The form includes space for annotations (ie, for judgments) by ASH, a summary of the interests that ASH judged to be conflicts, and a description of any special management strategy applied, for example, recusal. The form is maintained during the guideline-development process and finalized before submission of the guidelines for journal publication.

On publication, the complete forms of both the guideline panel and the systematic review team are included as supplemental files to the article. This transparency is intended to allow users to make their own judgments about any conflicts and how they were managed.

Questions.

ASH guideline panels prioritize questions using a variety of techniques, including discussion, surveys, and voting.47 For every prioritized question, the panel also prioritizes clinical outcomes that are critical or important for decision-making.47,48 The prioritized questions, including outcomes, are reported in the guidelines and the EtD frameworks. Some ASH guidelines also include as supplemental files the results of any prioritization surveys. This information may guide future efforts by ASH or by other guideline developers to provide additional guidance on the same topic.

EtD frameworks.

EtD frameworks are developed to assist panels in using evidence in a structured and transparent manner. The EtD frameworks included in published ASH guidelines represent exactly, without editing, what the panels considered and what they chose to document about this process. Examples are available through the hyperlinks in this article. Consider, for example, the question on parenteral anticoagulants as thromboprophylaxis for acutely ill medical patients (https://guidelines.gradepro.org/profile/54B577E9-7F80-3A78-B3EA-3850E9A1D432). The panel considered the question as a priority, assumed the observed reduction in VTE events (between 0 and 4 fewer per 1000 treated patients) as a small benefit, and the increase in major bleeding (3 more per 1000 treated patients) as a small undesirable effect. They judged the overall certainty in the evidence as low due to risk of bias; most studies had significant methodological limitations (unclear allocation concealment or lack of blinding) and imprecision (95% confidence intervals [CIs] for estimates of effect included appreciable benefit and no benefit for some critical outcomes). Based on the results of multiple studies that addressed patients’ values, the panel assumed no significant variability as almost every patient would place higher value on avoiding VTE events. With respect to resources and cost-effectiveness, the panel decided that implementing the intervention would possibly not result in significant costs or savings and would probably be cost-effective. Finally, the members of the panel agreed that the intervention would not affect equity, would be acceptable to all stakeholders, and would be feasible to implement (https://guidelines.gradepro.org/profile/54B577E9-7F80-3A78-B3EA-3850E9A1D432).

The panel issued a conditional recommendation in favor of the intervention. The decision was based on the judgment that the desirable consequences of the intervention were greater than the undesirable ones, but the certainty in the evidence was low.

The EtD frameworks also document by name which panel members participated on each guideline question and who was recused for a conflict of interest. Under ASH policy, any panelist with a current, direct financial interest in a commercial entity that marketed any product that could be affected by a recommendation addressing the question was permitted to participate in discussion about the evidence and clinical context, but was recused from making judgments or voting about individual GRADE domains or the direction and strength of the recommendation. Panelists also sometimes recused themselves for other reasons, for example, an intellectual conflict. In combination with the disclosure-of-interest forms, the EtD frameworks thus provide additional transparency around how conflicts of interest were managed.

Understanding the evidence summaries

Evidence behind the judgments.

Using the GRADE approach, every decision and judgment reached by the panel members is intended to be supported by the best available evidence. For this purpose, the evidence synthesis team develops evidence summaries that are included in the EtD and reviewed by the panel to reach every decision. For example, for the VTE guidelines, evidence acquisition and summarization was conducted by the McMaster GRADE Centre. Researchers followed the general methods outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (https://training.cochrane.org/handbook) for conducting updated or new systematic reviews of intervention effects. When the methodological team identified existing reviews, they implemented critical appraisal tools to decide whether those could be used and if they needed updates. The same team checked original authors’ judgments on risk of bias for accuracy. They decided to accept those judgments or conduct their own assessment if the original authors’ judgments were not available, not reproducible, or inaccurate. For new reviews, risk for bias was assessed at the health-outcome level using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk-for-bias tool for randomized trials or nonrandomized studies. In addition to conducting systematic reviews of intervention effects, the researchers searched for evidence related to baseline risks, values, and preferences, resource use and cost-effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability, then summarized findings within the EtD frameworks.

Summary-of-findings tables.

The balance between benefits and harms is 1 of the key determinants of the direction and strength of recommendations. Guideline users can find a description of the benefits, harms, and certainty in the evidence associated with every intervention in the main section of the guidelines. Additionally, for most recommendations, this information is available in table format (interactive summary-of-findings [SoF; iSoF] table) in the linked EtD frameworks. These tables provide a concise summary of the key information that is needed by someone making a decision and, in the context of a guideline, provide a summary of the key information underlying a recommendation. Tables 3 and 4 provide a SoF example and explanations of the individual components included in the table, respectively.

Table 3.

Example of an SoF table

| AAP compared with no AAP for pregnant women with prior VTE* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty in the evidence (GRADE)† | Relative effect, RR (95% CI)‡ | Anticipated absolute effects | |

| Risk with no AAP | Risk difference with AAP | ||||

| Recurrent major VTE (PE or proximal DVT) | 1519 (11 observational studies)53§|| | ⊕⊕◯◯ Low | 0.39 (0.21-0.72) | 42 per 1000 | 26 fewer per 1000 (33 fewer to 12 fewer) |

| Major bleeding, antepartum | 943 (6 RCTs)54¶ | ⊕⊕◯◯ Low# | 0.34 (0.04-3.21) | 6 per 1000 | 4 fewer per 1000 (6 fewer to 14 more) |

| Major peripartum bleed | 799 (8 RCTs)54¶ | ⊕⊕◯◯ Low# | 0.82 (0.36-1.86) | 30 per 1000 | 5 fewer per 1000 (19 fewer to 26 more) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 945 (8 RCTs)54 | ⊕◯◯◯ Very low#** | 2.37 (0.92-6.11) | 13 per 1000 | 17 more per 1000 (1 fewer to 64 more) |

Bates et al.1 Click here for interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_01618857-BE05-A8CA-8C89-E76E69C5FDD3-1582467465073?_k=w7ov9s.

AAP, antepartum anticoagulant prophylaxis; RR, risk ratio; SoF, summary of findings.

Patient or population: pregnant women with prior VTE. Setting: inpatient or outpatient setting. Intervention: antepartum anticoagulant prophylaxis. Comparison: no antepartum anticoagulant prophylaxis.

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence: high certainty, we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect; moderate certainty, we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different; low certainty, our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect; very low certainty, we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

Total of 11 studies; 8 had a group that received antepartum prophylaxis; 9 had a group with no antepartum prophylaxis. Of the 11, 7 were retrospective, 4 were prospective (3 were randomized comparisons).

Provoked, unprovoked, or estrogen associated in LMWH.

Most women had a history of placenta-mediated pregnancy complications; none had a history of prior VTE.

The very low event rate leads to uncertainty.

Not a direct outcome of interest, which leads to uncertainty.

Table 4.

Understanding of SoF tables

| Examples for tables | Explanations |

|---|---|

| Outcomes | The tables provide the findings for the main outcomes for someone making a decision, which were prioritized by the panel. These include potential benefits and harms, which are listed whether the included studies provide data for these outcomes or not. |

| No. of participants (studies): 1519 (11 observational studies) (recurrent major VTE outcome) | The table provides the total number of participants across studies (1519 in this example) and the number of studies11 that provided data for that outcome. This indicates how much evidence there is for the outcome. The references for the included studies are listed below the table. |

| Certainty in the evidence (GRADE) | The quality of the evidence is a judgment about the extent to which we can be confident that the estimates of effect are correct. These judgments are made following the GRADE approach and are provided for each outcome. The judgments are based on the type of study design (randomized trials vs observational studies), the risk of bias, the consistency of the results across studies, the directness of the evidence, and the precision of the overall estimate across studies. For each outcome, the quality of the evidence is rated as high, moderate, low, or very low. |

| Relative effect (95% CI): RR 0.39 (0.21-0.72) (recurrent major VTE outcome) | Relative effects are ratios. Here, the relative effect is expressed as an RR. Risk is the probability of an outcome occurring. An RR is the ratio between the risk in the intervention group and the risk in the control group. If the risk in the intervention group is 1% (10 per 1000) and the risk in the control group is 10% (100 per 1000), the relative effect is 10/100 or 0.10. If the RR is exactly 1.0, this means that there is no difference between the occurrence of the outcome in the intervention and the control group. If the RR is >1.0, the intervention increases the risk of the outcome. If it is a good outcome (for example, the birth of a healthy baby), an RR >1.0 indicates a desirable effect for the intervention; whereas, if the outcome is bad (for example, VTE), an RR >1.0 would indicate an undesirable effect. In the example in Table 3, the RR of 0.39 informs us that the risk of VTE was decreased with the intervention, which represents a desirable effect. |

| Confidence interval | A CI is a range around an estimate that conveys how precise the estimate is; in this example, the result is the estimate of the intervention risk. The CI is a guide to how sure we can be about the quantity we are interested in (here the anticipated absolute effect). The narrower the range between the 2 numbers, the more confident we can be about what the true value is; the wider the range, the less sure we can be. The width of the CI reflects the extent to which we are uncertain in the observed estimate (with a wider interval reflecting more uncertainty). |

| 95% CI | As explained previously, the CI indicates the extent to which chance may be responsible for the observed numbers. In the simplest terms, a 95% CI means that, if we repeat the same study infinite times, the true size of effect will be included between the lower and upper confidence limit (eg, 0.21 and 0.72 in the example of a relative effect recurrent major VTE in Table 3) in 95% of those studies. Conversely, 5% of the studies will provide 95% CIs that do not include the true size of effect. |

| Anticipated absolute effects | Absolute risks Risk is the probability of an outcome occurring. The estimated risks columns in the SoF table present the best estimate of the risk in the control group (risk with no antepartum anticoagulant prophylaxis in the Table 3 example) and the reduction risk in the intervention group (risk with antepartum anticoagulant prophylaxis in the Table 3 example), expressed as a value per 1000 patients, with a CI around the risk in the intervention group. Some versions of SoF tables include the risk in the intervention group without the risk difference. This can be chosen by the creator. |

| Estimated risk control: 42 per 1000 (recurrent major VTE outcome) | Estimated control risks (without the intervention; risk with no antepartum anticoagulant prophylaxis in the example in Table 3) are typical rates of an outcome occurring without the intervention. They will ideally be based on observational studies of incidence in representative populations. Alternatively, if such studies are not available, they can be based on the control group risks in comparative studies. When only 1 control group risk is provided, it is normally the median control group risk across the studies that provided data for that outcome. In this example (recurrent major VTE), the risk of 42 events occurring in every 1000 people indicates what would happen in a typical control group population. When relevant, the tables will provide information for >1 population, for instance differentiating between people at low and high risk when there are potentially important differences. |

| Intervention risk: 26 fewer per 1000 (33 fewer to 12 fewer) (recurrent major VTE outcome) | In this example, the estimated risk in the control group was 42 events in every 1000 persons. Implementing the intervention in this population would result in an intervention group risk of 16 events in every 1000 people, given the pooled RR across studies. The intervention results in 26 fewer patients with VTE events in every 1000 with a corresponding CI. If the table provides >1 control risk for an outcome, for instance, differentiating between people at low and high risk, then an intervention risk is provided for each population. Determining the effect of the intervention requires subtraction. |

| Difference between relative and absolute effects | The effect of an intervention can be described by comparing the risk of the control group with the risk of the intervention group. Such a comparison can be made in different ways. One way to compare 2 risks is to calculate the difference between the risks. This is the absolute effect. The absolute effect can be found in the SoF table by calculating the difference between the numbers in the control risk in the control group on the left and the intervention risk in the intervention group on the right. Here is an example: consider the risk for blindness in a patient with diabetes over a 5-y period. If the risk for blindness is found to be 20 in 1000 (2%) in a group of patients treated conventionally and 10 in 1000 (1%) for patients treated with a new drug, the absolute effect is derived by subtracting the intervention group risk from the control group risk: 2% − 1% = 1%. Expressed in this way, it can be said that the new drug reduces the 5-y risk for blindness by 1% (absolute effect is 10 fewer per 1000). Another way to compare risks is to calculate the ratio of the 2 risks. Given the data in the blindness example, the relative effect is derived by dividing 2 risks, with the intervention risk being divided by the control risk: 1%/2% = 1/2 (0.50). Expressed in this way, as the ‘‘relative effect,’’ the 5-y risk for blindness with the new drug is one-half the risk with the conventional drug. Here, the table presents risks as times per 1000 instead of as a percentage, as this tends to be easier to understand. Whenever possible, the table presents the relative effect as the RR. Usually the absolute effect is different for groups that are at high and low risk, whereas the relative effect often is the same. Therefore, when it is relevant, GRADE tables report risks for groups at different levels of risk. |

| Explanations | Explanatory notes are provided below the table and include explanations of the judgments for rating down the certainty in the evidence, as well as any additional clarifications for users. |

Schünemann.40

Evidence summaries on other key aspects.

In addition to SoF tables about the effects of the interventions on critical and important outcomes, summaries prepared for evidence on patients’ values, resource utilization, impact on equity, acceptability, and feasibility are provided in the EtD frameworks. These are provided in different formats depending on the criteria being considered. For example, evidence summaries on values and the importance of outcomes include estimates of the relative importance of the outcomes, in the form of utilities (utility values range from 0 to 1; death is anchored at 0, whereas 1 represents perfect health) as well as narrative summaries.49 Resource-utilization and cost-effectiveness evidence can include direct costs of the interventions and outcomes from different settings and perspectives (eg, individual patient or health system perspective, inpatient and outpatient costs), as well as narrative summaries of relevant economic analyses (eg, cost-benefit, cost-effectiveness analyses). Evidence about impact on health equity, acceptability, and feasibility of the interventions is typically described using narrative statements. When no such evidence is identified by the evidence synthesis team, a statement is included in the EtD fields or they are left blank.

Using the guidelines

Where to find the guidelines

The ASH Web site (hematology.org/guidelines) provides direct access to the clinical practice guidelines and other products that are derived from the guideline recommendations, including patient versions and, in the future, decision aids.

From recommendations to decisions

To improve usability and implementation, ASH guidelines are provided in different formats, and recommendations can be accessed through different interfaces. Guideline users can choose to access ASH guidelines in different ways, depending on the context. For example, a busy clinician at the point of care aiming to make a straightforward treatment decision may look for the corresponding guideline recommendation without attempting to gain further insight into the evidence and judgments supporting that recommendation. He or she may reach the recommendation in the summary-of-recommendations section of the guideline document or through the mobile app. In a different context, a medical center director defining an institutional policy may assess the recommendation as well as the supporting information before reaching a decision. He or she may find the required information in the main section of the guideline document as well as the linked EtD frameworks.

When should guideline users drill into the supporting evidence for a recommendation? Although using the guideline by looking at the recommendations without gaining further insight into the supporting information might seem attractive, especially for the busy clinician, it is not an advisable way of implementing these documents in many situations, in particular in the context of conditional recommendations. Thus, guideline users should account both for the direction and the strength of the recommendations. When the required conditions are met and a strong recommendation is issued, guideline users can be confident that following the proposed course of action is the appropriate decision in most instances. Hence, they should place the focus on defining whether the proposed recommendation applies to the clinical scenario they are facing. On the other hand, in situations in which those conditions are not met and a conditional recommendation is issued, understanding the evidence and judgments behind the recommendation becomes essential to define the best course of action. Appropriately implementing a conditional recommendation may require patient involvement in a shared decision-making process (see next paragraph) or it may demand a thorough analysis of the clinical scenario, as the direction of the recommendation may change in some specific subgroups or contexts. Guideline users can find the necessary information to appropriately implement the recommendations in the following sections of the linked EtD frameworks: “Justification,” “Subgroup considerations,” “Implementation considerations,” and “Monitoring and evaluation.” A summary is also available in the main sections of the guideline documents under “Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation” and as a part of the recommendations in the remarks.

Consider a healthy male adult, without VTE risk factors, who asks his physician about using compression stockings to prevent VTE during a long airplane trip. In the course of the consultation, the physician could access the online version of the ASH clinical practice guideline on VTE prophylaxis for medical patients and reach for Recommendation 18 in the summary-of-recommendations section: “In long-distance (>4 hours) travelers without risk factors for VTE, the ASH guideline panel suggests not using graduated compression stockings, LMWH, or aspirin for VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, very low certainty in the evidence of effects)”. Considering that the strength of the recommendation is conditional, the physician decides to gain further insight by accessing the EtD (https://guidelines.gradepro.org/profile/916AAFBA-F72C-2CBE-BD33-8EA86A031824) provided in the guideline’s main section under question 18.5 After realizing that the panel judged both benefits and harms as trivial, the physician decides to explore the evidence behind those judgments and accesses the iSoF by clicking on the corresponding tab. The physician notes that the undesirable effects of the intervention are mainly related to the burden of wearing the stockings and the magnitude of the benefits are on the order of 1 less proximal DVT episode per 2000 to 5000 persons using stockings during a long flight. As the physician is not sure what her patient would decide, she opts to use a tool to facilitate decision-making. She provides the patient with a patient version of the recommendation (see “Patient versions of the recommendations”), available at https://www.hematology.org/Clinicians/Guidelines-Quality/8743.aspx, and discusses the information included with him. In line with the recommendation, the patient considers that the potential benefits are too small to justify the burden of using the stockings during the flight and decides not to use them.

Implementation tools

The ASH guidelines on VTE include a series of tools to facilitate implementation of recommendations. Some tools aim to improve patients’ involvement in decision-making by empowering them with information presented in a way that they can understand, and others are focused on facilitating access to the recommendations for decision-making and teaching. Similar tools for other ASH guidelines are planned.

iSoF tables

iSoF tables present the same underlying information as standard SoF tables, but allow for several formats that vary in content and graphical layout generated by the GRADEpro app.50 The objective of iSoF tables is to improve understanding and use of evidence of the effects of health care interventions by allowing producers of iSoF tables to tailor a presentation to a target audience and users to interact with the presentation by viewing more or fewer outcomes; more or less information about each outcome; information about the absolute effects as numbers, words, or graphs; and explanations and links to more detailed explanations of basic concepts (eg, “95% CI”) and specific content (eg, a specific outcome such as a pain scale). Main features of iSoF tables include:

layers of information for drilling down from simple to complex;

choice of viewing evidence as text, numbers, or graphics;

step-by-step visualizations that help explain results, including CIs;

interactive explanation of terms;

interactive explanatory footnotes;

responsive design (will automatically adapt to small screens or device displays); and

availability in different languages.

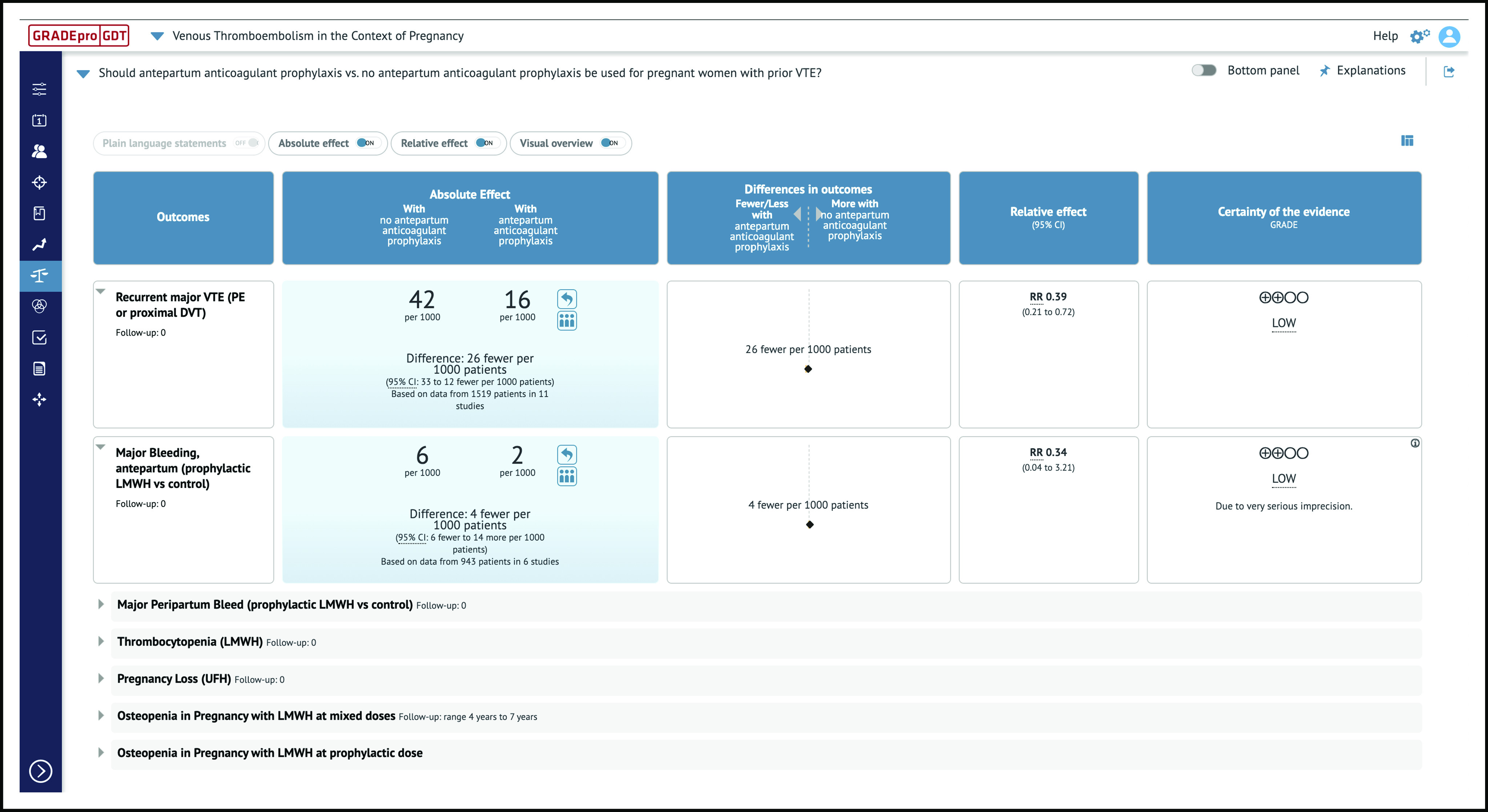

iSoF tables are available in the linked EtDs for all recommendations. Figure 1 provides an example of an iSoF table for a question about antepartum anticoagulant prophylaxis vs no antepartum anticoagulant prophylaxis in pregnant women with prior VTE. In this example, the user decided to focus on 2 of the available outcomes, recurrent major VTE and major bleeding, and chose to present the absolute effects as well as a visual overview of those effects.

Figure 1.

iSoF table. An example of an iSoF table1 that can be used to explore an intervention’s effect on health outcomes in alternative ways. It includes the question, outcomes, relative and absolute effects, and interpretations (https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_01618857-BE05-A8CA-8C89-E76E69C5FDD3-1582467465073?_k=w7ov9s).

Patient versions of the recommendations

Patient versions include information about key recommendations and their supporting elements presented in a patient-friendly format. The main purpose of this tool is to empower patients with the necessary information so that they can confidently be involved in the decision-making process. Patient versions of the recommendations are available on the ASH Web site for selected recommendations (https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/premium/premium_presentation:p_tjcranford_c527c3c8-ee25-4c71-8b29-89898ea71f49_A468DACE-5F08-C446-8485-3589A5C0CCBF?_k=qdwm36).

Pocket guides and teaching slide sets

These tools, available on ASH’s Web site (hematology.org/vteguidelines), provide a summarized version of guideline content presented in a way that facilitates point-of-care usage and teaching.

ASH guideline app

The ASH Clinical Practice Guidelines App (https://www.hematology.org/Apps/) provides easy access to every recommendation from all guidelines published by ASH, including the rationale for each recommendation, benefits and harms associated with each recommended course of action, and links to the complete EtD frameworks used to develop the recommendations.

The ASH guideline app contains the complete ASH VTE guidelines presented in a multilayered, user-friendly format. Users can choose between 3 different approaches. (1) In recommendations, they can select the relevant recommendation by exploring the questions by clinical scenario and gain access to information on panel judgments, benefits and harms, and certainty in the evidence. Users can also explore the SoF table supporting every particular recommendation. (2) In executive summary, all of the recommendations in the selected guideline are presented in a short, easy-to-read article that contains only the recommendations, certainty in the evidence statements, and remarks. (3) In full guideline, the complete guidelines are available as published.

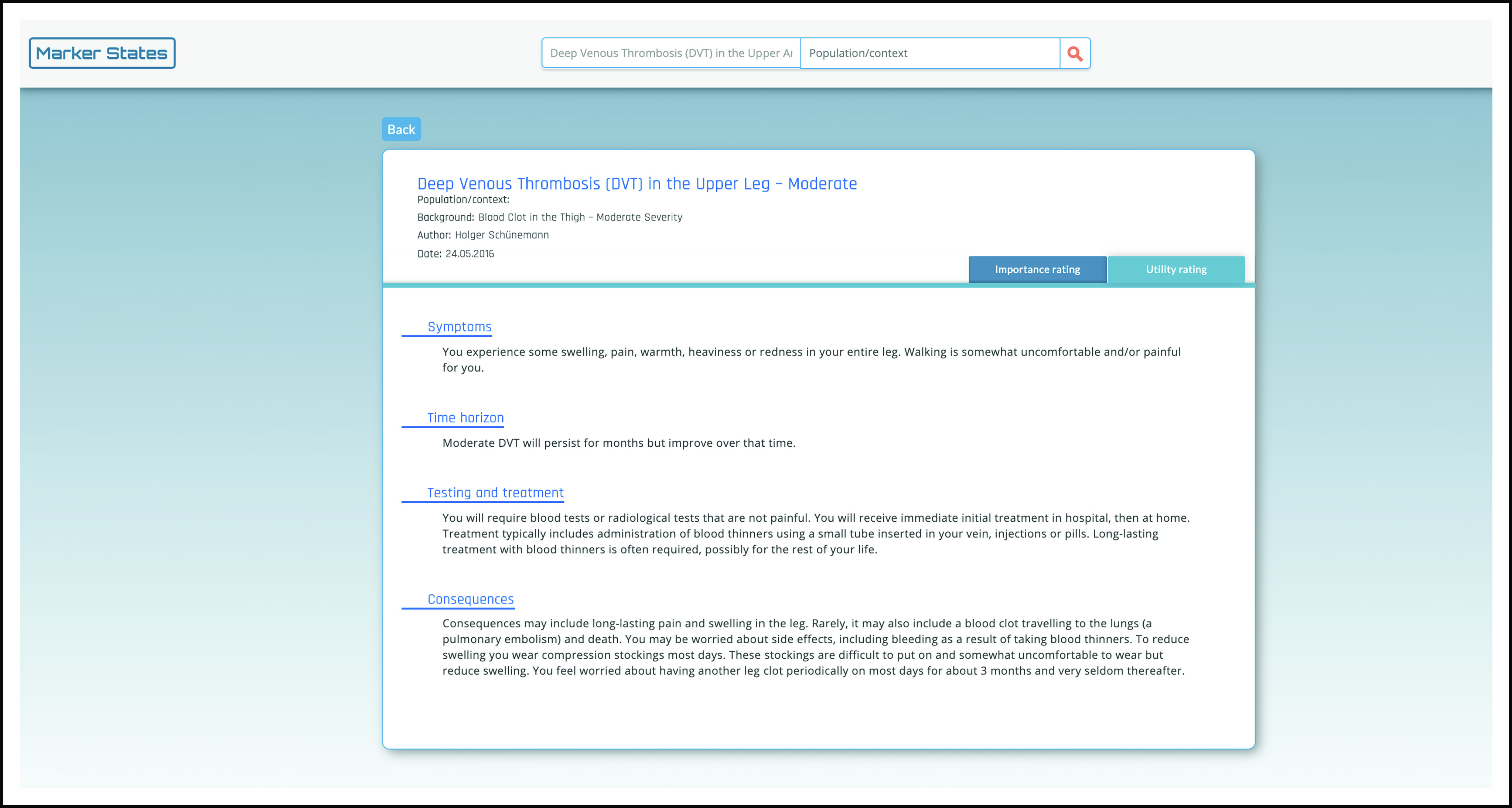

Health-outcome descriptors or marker states

A new feature of some ASH guidelines is the use of marker states that describe health outcomes in lay terms for patients and practitioners.51 The purpose of these marker states, or health-outcome descriptors (HODs), is to establish common definitions of patient-important outcomes to better inform the guideline panel’s decision-making. Health outcomes reported in trials and those encountered in clinical practice may have varying definitions with varying consequences for patients (eg, screening-detected asymptomatic DVT vs symptomatic proximal DVT, or a mild distal DVT vs a severe proximal DVT). HODs describe patient-important outcomes with respect to symptoms, time horizon, implications for testing and treatment, and consequences for an individual patient (Figure 2). They help to ensure that panel members share a common understanding during the prioritization of critical and important outcomes. The evidence synthesis team then abstracts outcome data from intervention studies that match, or are most direct, to those outcomes prioritized by the panel. When weighing desirable and undesirable consequences of interventions to formulate a recommendation, the HODs also serve as a reference point to help panel members conceptualize the same outcomes and consequences for a patient. Moreover, for outcomes that may not be well defined in research studies but are critical or important for decision-making during guideline development (eg, use of antileukemic therapy at the end of life), developing a marker state allows the panel to construct a working definition to inform their deliberations, as well as to inform future research. Marker states developed for outcome prioritization and utility rating by clinical experts and methodologists are available on the Marker States database at https://ms.gradepro.org.

Figure 2.

Example HOD. The purpose of these marker states, or HODs, is to establish common definitions of patient-important outcomes to better inform the guideline panel’s decision-making by including definitions of the consequences for people in terms of symptoms, time horizon, testing and treatment, and consequences (eg, moderate symptomatic proximal DVT) (https://ms.gradepro.org/marker-states/ce16bfaf-cd4d-4138-9c06-1784e3a5413f).

Decision aids

ASH will be developing decision aids and has begun production. Decision aids will allow for shared decision-making with patients. They will present all key information in an interactive format.

ASH VTE guideline adaptations

As the relevant aspects that determine the direction and strength of recommendations may significantly differ in different contexts, recommendations developed within a specific set of circumstances may need adjustments to be implemented in a different setting. Effects of interventions seldom differ from 1 jurisdiction to another. However, other relevant aspects such as patients’ values and preferences, resource availability, and implementation issues often do. The ASH VTE adaptation project aims to adapt the original ASH VTE guideline recommendations to different contexts by assembling local expert panels that will make their own judgments based on the same evidence used in the original guidelines, as well as additional evidence that may be considered relevant to the local context (eg, a study on patients’ values and preferences performed in Latin America). ASH is currently undertaking an adaptation of its VTE guidelines with a panel of experts from Latin American countries. This project uses the GRADE Adolopment approach: a combination of adoption, adaptation, and de novo recommendations focused on the use of existing EtDs.52 The resultant adapted recommendations, which may differ in direction and/or strength from the original ones, will be published and available on the ASH Web site.

Conclusions

This user-guide document provides insight into the ASH guidelines-development process and how it adheres to the IOM standard of trustworthy guidelines. The user guide also provides a detailed description of the structure and content presentation of ASH guidelines. Readers are encouraged to use this document as a companion to the original ASH guidelines to facilitate appropriate interpretation and implementation of recommendations.

Acknowledgments

ASH funded development of the ASH guidelines and systematic evidence reviews discussed in this article. This funding indirectly supported the writing of this article by providing salary support to some of the authors, including ASH staff and researchers employed by or contracted to the McMaster University GRADE Centre. D.T. was supported by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number 1K01HL135466. J.P. has received funding from the National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases) and the Health Resources and Services Administration.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute did not have any involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

For original data, please contact ariel.izcovich@gmail.com.

Authorship

Contribution: H.J.S., A.I., R.K., A.C., M.S., R.P., W.W., and R.N. conceptualized the guide; H.J.S. and R.P. acquired funding; H.J.S., A.I., R.K., A.C., W.W., and R.N. developed the methodology; H.J.S. and A.I. were project administrators who visualized and supervised the project; H.J.S. provided software; H.J.S., A.I., R.K., and A.C. wrote the original draft of the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.C. has served as a consultant for Synergy CRO, and has received institutional research support from Alexion, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi, Spark, and Takeda. M.S. has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Jazz, AbbVie, and Roche, and has received research funds from Teva. M.B. has received research funding from Karyopharm. R.K. is employed by ASH, which has funded and disseminated the guidelines discussed in this article. M.P. has served as a consultant for Pfizer (advisory board) and has received speaker honorarium from Novartis. H.J.S. has received funding for this project from ASH and for multiple other projects on guideline development from various organizations, and consultant fees for supporting guideline development; is an author of the Marker State database and GRADEpro, which is programmed by EvidencePrime, a company partially owned by his employer McMaster University; has not received personal payments for the use of GRADEpro; and is cochair of the GRADE Working Group. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ariel Izcovich, Department of Internal Medicine, German Hospital, Pueyrredón 1640, C1118 AAT, Buenos Aires, Argentina; e-mail: ariel.izcovich@gmail.com; or Holger J. Schünemann, McMaster University, HSC-2C, 1280 Main St West, Hamilton, ON L8N 3Z5, Canada; e-mail: schuneh@mcmaster.ca.

References

- 1.Bates SM, Rajasekhar A, Middeldorp S, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: venous thromboembolism in the context of pregnancy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3317-3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuker A, Arepally GM, Chong BH, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3360-3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim W, Le Gal G, Bates SM, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3226-3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monagle P, Cuello CA, Augustine C, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 Guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of pediatric venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3292-3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198-3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witt DM, Nieuwlaat R, Clark NP, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3257-3291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson DR, Morgano GP, Bennett C, et al. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients. Blood Adv. 2019;3(23):3898-3944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortel TL, Neumann I, Ageno W, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Manuscript submitted March 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]