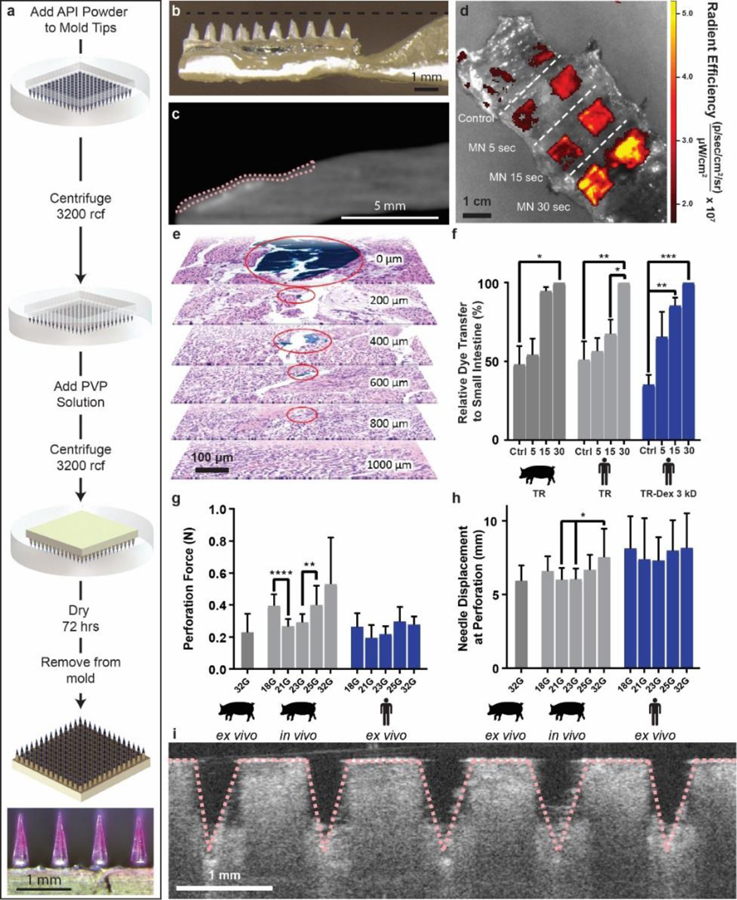

Fig. 3.

Polyvinylpyrrolidone microneedle (MN) characterization in the small intestine. (a) Microneedles were fabricated using solid API powder to increase their drug loading. A single patch 1 cm2 held up to 0.6 mg in the tips alone. The microneedle patch pictured contained Texas red dye. (b) LUMI arms contained an indentation to house insulin loaded microneedles during encapsulation. (c) MicroCT image of a barium sulfate loaded microneedle patch applied to a section of human small intestine using the LUMI. The tissue is outlined in pink. (d) Texas red microneedle dissolution in human tissue. In the control experiment, patches were not penetrated into tissue but were left on the tissue for 30 s. (e) Histology confirmed that needles applied to the small intestine ex vivo using the LUMI penetrated but did not perforate the tissue. Surgical dye used to coat the needle reached 800 μm below the surface of the tissue (f) Relative dye transfer over time (seconds) of microneedles to small intestine tissue (n=3 over 3 samples). (g) Force and (h) displacement required for needle perforation in the small intestine (n=15 over 3 samples). (i) Optical Coherence Tomography imaging confirmed that microneedles penetrated into the small intestine tissue. (Error Bars=SD; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001).