Abstract

Background:

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN) is a common complication in individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM) but often overlooked in clinical practice. The burden and correlates of CAN have not been extensively studied in low-income countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.

Objectives:

To determine the prevalence and correlates of CAN among adults in ambulatory diabetes care in southwestern Uganda.

Method:

We conducted a cross-sectional study among adults with diabetes from November 2018 to April 2019. CAN was assessed using the five autonomic function tests: deep breathing, Valsalva maneuver, postural index on standing, change in blood pressure during standing and diastolic blood pressure response to isometric exercise. We estimated the prevalence of CAN and fit regression models to identify its demographic and clinical correlates.

Results:

We enrolled 299 individuals. The mean age was 50.1 years (SD ± 9.8), mean HbA1c was 9.7 (SD ± 2.6) and 69.6% were female. CAN was detected in 156/299 (52.2%) of the participants on the basis of one or more abnormal cardiovascular autonomic reflex tests. Out of 299 participants, 88 (29.4%) were classified as early CAN while 61/299 (20.4%) and 7/299 (2.3%) were classified as definite and severe (advanced) CAN respectively. In multivariable regression models, age over 50 years (aOR 3.48, 95%CI 1.35 –8.99, p = 0.010), duration of diabetes over 10 years (aOR 4.09, 95%CI 1.78 –9.38, p = 0.001), and presence of diabetic retinopathy (aOR 2.25, 95%CI 1.16 –4.34, p = 0.016) were correlated with CAN.

Conclusions:

Our findings reveal a high prevalence of CAN among individuals in routine outpatient care for diabetes mellitus in Uganda. Older age, longer duration of diabetes and coexistence of retinopathy are associated with CAN. Future work should explore the clinical significance and long term outcomes associated with CAN in this region.

Keywords: Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, Prevalence, Diabetes, Uganda

Background

The global prevalence of diabetes is 8.5%, with an estimated 422 million people living with the disease [1]. As of 2014, the prevalence of diabetes was higher in low-income (7.4%) than in high-income (7.0%) countries [2]. Moreover, it is estimated that the disease burden will increase by approximately 70% in low income countries by 2030 [3,4]. Sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, is believed to have the highest proportion of undiagnosed diabetes with more than two-thirds of people with diabetes unaware of their status [5,6].

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN) is defined as an impairment of cardiovascular autonomic control in people with diabetes with other causes excluded [7,8]. Cardiovascular reflex tests that are based on provocative physiological maneuvers of the autonomic nervous system (Valsalva maneuver, supine to standing, deep breathing and sustained hand grip) are commonly used in the detection of CAN [9]. There is no particular algorithm for the diagnosis of CAN, though it is recommended that more than one test be carried out to increase the reliability and sensitivity for proper diagnosis of the condition [10]. The occurrence of CAN, on the basis of at two or more tests [7,11,12] ranges from approximately 20% to 65%, with older age and longer duration of disease [13,14]. CAN is associated with an increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias, silent myocardial ischemia and sudden death [10,15]. Hence, it may limit exercise capacity and is associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events during exercise [16]. Moreover CAN is associated with increased risk of mortality [17]. Previous longitudinal studies among diabetic individuals with CAN have reported five-year mortality rates of up to 50%, often due to sudden cardiac death [18]. Despite these complications, CAN remains largely undiagnosed among individuals with diabetes. Nonetheless, early detection and treatment of CAN may prevent cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients [19], since there is evidence to suggest that cardiovascular denervation can be reversed early in the course of the condition [9,20].

Despite the high prevalence of diabetes in low-resource settings, most studies on prevalence and correlates of CAN have been done in high-resource settings. There are particularly few data on the condition in Sub-Saharan Africa. In this clinic-based survey, we aimed to determine the prevalence and correlates of CAN among individuals with diabetes in ambulatory diabetes care in southwestern Uganda.

Methods

Study population

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the diabetes and endocrinology outpatient clinic of Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH), Western Uganda. MRRH is a government-operated referral centre and the teaching hospital of the Medical School of Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST), serving a population of over four million people in its catchment area. The diabetes and endocrinology ambulatory care clinic is operated once per week and attends to an average of 100 patients per week. A total of about 1,500 diabetic patients are registered at the clinic.

Study participants were individuals with diabetes attending MRRH diabetes and endocrinology ambulatory clinic. We included participants aged 18 to 65 years with a clinical diagnosis of diabetes. We defined diabetes in those with a fasting blood glucose concentration greater than 7.0 mmol/l, or in those actively taking medications for diabetes [21,22,23]. We excluded individuals with a self-reported history of cardiac, respiratory, renal, hepatic, cerebrovascular, thyroid or other endocrine abnormalities. We also excluded individuals with previous ECG abnormalities, an acute illness in the last 48 hours, and those who had consumed beverages containing caffeine or alcohol within the past 12 hours. Finally, we excluded individuals actively taking calcium channel blockers or beta-blockers, which can interfere with the CAN screening battery [24].

Study Procedures and Definitions

We administered a standardized questionnaire to capture data on socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, including their data on smoking, alcohol use and diabetes treatment history. The diabetes treatment history was self-reported and verified by clinic records for those participants who had a chat available for review. Height, weight, hip circumference, and waist circumference were collected. We computed body mass index (BMI) by dividing participants’ weight (in kilograms) by the height in metres squared (m2), and categorized BMI as normal, underweight, overweight and obese [25]. Abdominal obesity was defined as a waist circumference ≥102 cm in males and ≥88 cm in females [25]. Blood pressure was measured using an upper arm automated sphygmomanometer (Omron HEM 705 LP, Omron Healthcare, Inc., Bannockburn, IL, USA) in a seated position. Participants were considered to have arterial hypertension if their blood pressure values were ≥140/90 mmHg and/or taking medications for hypertension [26]. Intensity of physical activity was expressed in metabolic equivalent task (MET) as derived from the questionnaire using the WHO GPAQ analysis tool [27]. The presence of diabetic retinopathy was detected with direct ophthalmoscopy after pupillary dilation by an ophthalmologist. Diabetic retinopathy was classified or graded as non-proliferative (NPDR) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). We assessed for the presence of the following symptoms of distal peripheral neuropathy over the preceding 6 months: numbness or ‘dead feeling’ in the feet; a tingling sensation in the feet; deep, painful or burning aches in the lower limbs; and unusual failure in walking uphill or climbing staircases. The existence of one or more of the symptoms was classified as abnormal. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured according to the standard operating procedure of the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC) [28] using an automated high performance liquid chromatography analyzer (Cobas Integra 400, Roche diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) at the Lancet Laboratories.

The evaluation of CAN was done according to standardized protocols described previously [12]. Briefly, we considered five measures to diagnosis CAN, including: 1) deep breathing; 2) Valsalva maneuver; 3) postural index on standing; 4) change in blood pressure during standing and 5) diastolic blood pressure response to isometric exercise. A resting 12-Lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was taken for all the participants using a portable ECG machine (Edan Instruments, Inc., Hessen, Germany).

Deep breathing

While lying down, participants were asked to perform a deep and slow inspiration up to the maximum total lung capacity for five seconds, which was followed by a forced expiration down to the residual volume for five seconds. The time to alternate the respiratory cycle was signaled directly to the patient by the attending research assistant. We calculated the maximum and minimum R-R interval during the respiratory cycle, and converted these results to beats per minute. We defined R-R interval as the duration between two successive R waves. We considered a variation of less than 15 beats per minute between the two measures as abnormal.

Valsalva maneuver

We asked participants to exhale into a mouthpiece with their nose closed and to perform a continuous expiratory effort. This was equivalent to an intraoral pressure of 40 mmHg, for 15 seconds. We then asked participants to release the strain, and to breathe regularly until the end of the test. We calculated the ratio of the longest RR interval to the shortest RR interval following the pressure release. We considered a ratio less than 1.2 as abnormal. The test was performed three times, and we used the mean value in our analyses. Participants with evidence of proliferative retinopathy were excluded from the valsalva maneuver, because it is associated with a minor risk of intraocular hemorrhage or lens dislocation [7].

Measurement of postural index on standing

We again asked participants to lie supine quietly. After about 5 minutes with continuous monitoring, the participant was made to stand. We calculated the postural index (PI) by measuring the heart rate response to the change of position from recumbent to standing over 180 seconds after getting up. We calculated this as the ‘30–15 ratio,’ defined as the longest RR interval of beats 20–40 divided by the shortest RR interval of beats 5–25, starting from the first beat during the process of standing up. The postural index of <1.00 was considered abnormal.

Change in blood pressure during standing

We measured blood pressure with participants in recumbent position, every minute for three minutes, and then while standing, every minute for five minutes. We considered a drop of ≥20 mmHg in systolic blood pressure or ≥10 mmHg in diastolic blood pressure as abnormal.

Diastolic blood pressure response to isometric exercise

We asked participants to squeeze a hydraulic hand dynamometer (Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN, USA) at 1/3 of the maximum effort for about 5 minutes. We considered an abnormal diastolic blood pressure in response to isometric exercise as an increase in diastolic blood pressure <15 mmHg.

Measurement of QT interval

We measured the QT interval from the beginning of the QRS complex to the end of the down-slope of the T wave (crossing of the isoelectric line); when a U wave was present, the QT interval was measured until the bottom of the angle between the T and U waves [29]. We used Bazette’s formula to calculate a heart rate–corrected QT (QTc) [30]. QTc was the mean of QTc from five consecutive cycles in lead V5. We consider a maximum value of the QTc interval >440 ms to be elevated [31]. For quality control, two independent observers (DCA and GK) measured intervals. Both were blinded to participants’ data, and an average measure taken. The Pearson’s correlation coefficients for the agreement between the two observers were 0.92 and 0.87 for QTc and RR Intervals respectively. We performed ECG on the same day as glycaemic testing.

Sample size

A sample size of 296 participants was required to enable a 5% precision with a 95% confidence interval around an estimated CAN prevalence of 20% [32]. We entered data into EpiData3. (EpiData, Odense, Denmark), and used Stata for all analyses (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Statistical Analyses

Our outcome of interest was CAN, defined by the results of each of the above five classification components. We categorized CAN based on severity, as described previously (Table 1 [33]). We summed the points from each test to arrive at an overall CAN score, categorized as absent (0 points), early (0.5–1.5 points), definite (2–3 points), and severe (≥3.5 points) [12,34].

Table 1.

Algorithm for classification of CAN (CAN score).

| Tests | Point 0 | Point 0.5 | Point 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting heart rate | <100 beats/min | 100–110 beats/min | >110 beats/min |

| Postural hypotension (fall in systolic blood pressure) | <20 mmHg | 20–30 mmHg | >30 mmHg |

| Valsalva ratio | >1.2 | 1.2–1.10 | <1.10 |

| Heart rate variability on deep breathing | >15 beats/min | 15–10 beats/min | <10 beats/min |

| Increase in diastolic blood pressure during sustained handgrip | >15 mmHg | 15–10 mmHg | <10 mmHg |

CAN: Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy.

We first described the participant characteristics. Next we estimated the prevalence of CAN as the proportion of patients meeting the definition of CAN. We then assessed for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics comparing those with and without CAN, using chi-square testing to compare categorical variables, student t-tests for continuous variables, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Finally, we fit logistic regression models to identify correlates of CAN. Covariates with a P-value ≤ 0.2 in univariable models were included in multivariable models through backward stepwise elimination method. QTc interval was deliberately not included in the final model because it predicted the outcome perfectly.

Results

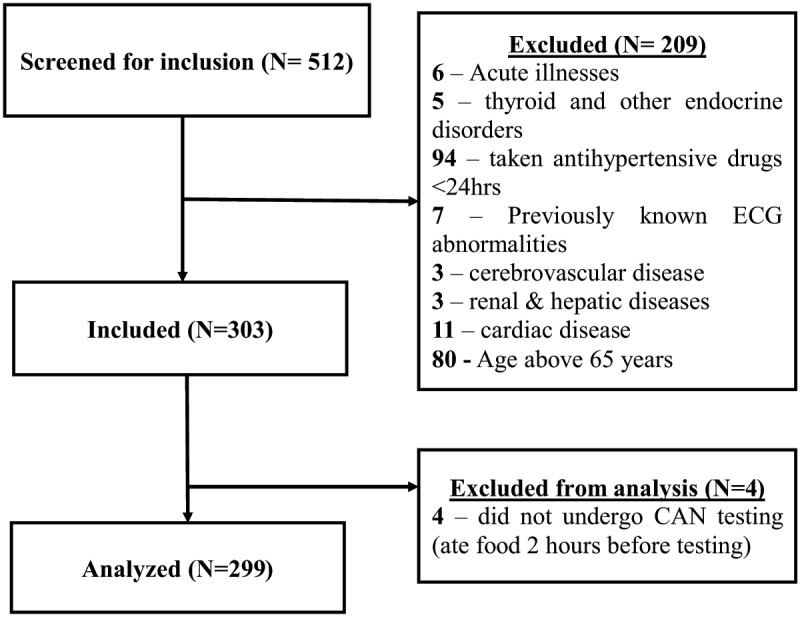

Out of the 512 diabetic patients screened for inclusion into the study between November 2018 and April 2019, we present results for 299 participants. The reasons for exclusion are described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study profile.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Social and demographic characteristics of study participants with and without CAN are presented in Table 2. Most participants were female (69.6%) and peasants by occupation (58.6%). More than half (69.9%) of the participants had never taken alcohol. The mean age of the participants was 50.1 (SD ± 9.8) years. Seventy participants (23.4%) had ever smoked. The clinical characteristics of the participants with and without CAN are presented in Table 2. The mean duration of diabetes was four years (IQR 1, 8). The mean fasting blood glucose and HbA1c were 11.2 mmol/l (SD ± 4.8) and 9.7% (SD ± 2.6), respectively. Out of the 299 participants, 68 (22.7%) had diabetic retinopathy.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by CAN status.

| Characteristic | Total cohort (N = 299) | Positive for CAN (N = 156) | No evidence of CAN (N = 143) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, in years, mean (SD) | 50.1 (±9.8) | 52.8 (±8.7) | 47.2 (±10.2) | <0.001 |

| Female sex (%) | 208 (69.6) | 122 (78.2) | 86 (60.1) | 0.001 |

| Ever attended school, yes (%) | 233 (77.9) | 115 (73.7) | 118 (82.5) | 0.067 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Peasant (%) | 175 (58.5) | 103 (66.0) | 72 (50.4) | 0.006 |

| Student (%) | 6 (2.0) | 2 (1.3) | 4 (2.8) | 0.351 |

| Businessman (woman) (%) | 64 (21.4) | 29 (18.6) | 35 (24.5) | 0.215 |

| Civil servant (%) | 51 (17.1) | 26 (16.7) | 25 (17.5) | 0.851 |

| Ever smoked, yes (%) | 70 (23.4) | 37 (23.7) | 32 (22.4) | 0.783 |

| Currently smoking, yes (%) | 18 (25.7) | 11 (29.0) | 7 (21.9) | 0.500 |

| Duration of diabetes in years, mean (SD) | 5.8 (±5.9) | 7.5 (±6.9) | 3.9 (±3.9) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.4 (±5.6) | 27.5 (±5.9) | 27.3 (±5.2) | 0.685 |

| Waist circumference in cm, mean (SD) | 98.2 (±13.6) | 99.9 (±14.3) | 96.4 (±12.7) | 0.025 |

| History of vigorous physical activity (≥600 METS/Week) (%) | 173 (57.9) | 89 (57.1) | 84 (58.7) | 0.087 |

| Fasting blood sugar in mmol/L, mean (SD) | 11.2 (±4.8) | 11.8 (±5.2) | 10.5 (±4.3) | 0.021 |

| HbA1c (%), mean(SD) | 9.7 (±6.7) | 9.7 (±2.5) | 9.6 (± 2.7) | 0.506 |

| Resting heart rate in beats/min, mean (SD) | 76.6 (±13.1) | 79.2 (±14.7) | 73.6 (±10.4) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure in mmHg, mean (SD) | 141.7 (±22.6) | 148.6 (±23.2) | 134.2 (±19.4) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure in mmHg, mean (SD) | 87.1 (±10.7) | 88.8 (±10.7) | 85.4 (±10.5) | 0.006 |

| Pulse pressure in mmHg, mean (SD) | 54.6 (±17.8) | 59.9 (±19.4) | 48.8 (±13.8) | <0.001 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 105.3 (±13.3) | 108.7 (±13.1) | 101.6 (±12.5) | <0.001 |

| Retinopathy | <0.001 | |||

| None (%) | 231 (77.3) | 106 (68.0) | 125 (87.4) | |

| Non-proliferative (%) | 53 (17.7) | 35 (22.4) | 18 (12.6) | |

| Proliferative (%) | 15 (5.0) | 15 (9.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| History of neuropathy symptoms in past 6 months | ||||

| Palpitations, yes (%) | 149 (49.8) | 93 (59.6) | 56 (39.2) | <0.001 |

| Fainting or blackouts, yes (%) | 114 (38.1) | 63 (40.4) | 51 (35.7) | 0.401 |

| ‘Dead feeling’, pricking or burning sensation in the feet, yes (%) | 183 (61.2) | 105 (67.3) | 78 (54.6) | 0.024 |

| QTc interval (ms), mean (SD) | 428.4 (±22.3) | 438.4 (±22.0) | 417.5 (±16.8) | <0.001 |

SD: Standard deviation; CAN: Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy; MET: Metabolic Equivalent Task.

Prevalence and correlates of CAN

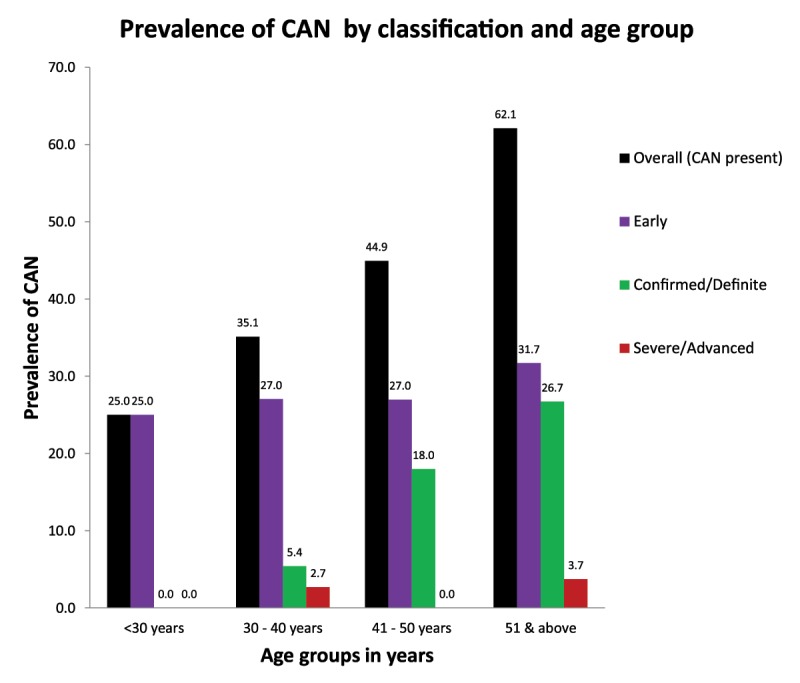

CAN was diagnosed in 156/299 participants for a prevalence of 52.2% (95% CI 46.3–58.0%) on the basis of one or more abnormal cardiovascular autonomic reflex tests. The classification of CAN on the basis of CAN score is presented in Table 4. Out of 299 participants, 88 (29.4%) were classified as early CAN while 61/299 (20.4%) and 7/299 (2.3%) were classified as definite and severe (advanced) CAN respectively on the basis of the CAN score. The prevalence of CAN as assessed by the various measures of autonomic neuropathy is presented in Table 3. The most common positive sub-scale of CAN was abnormal heart rate variability with deep breathing, which we detected in 125 individuals (42%). The prevalence and severity of CAN was highest in older age groups as shown in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Prevalence of CAN by severity (Classification of CAN).

| CAN category | Number of cases (n) | Percentage, n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| N = 299 | ||

| Absent | 143 | 47.8 |

| Early | 88 | 29.4 |

| Definite/Confirmed | 61 | 20.4 |

| Severe/Advanced | 7 | 2.3 |

| TOTAL | 299 | 100.0 |

Table 3.

Prevalence of CAN by the different assessment methods.

| Test/Method | Number of cases (n) | percentage, n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| N = 299 | ||

| Resting tachycardia (pulse rate ≥100 bpm) | 17 | 5.7 |

| Abnormal postural index (≤1.0) | 40 | 13.4 |

| HRV: Reduced E/I ratio with deep breathing (<15 bpm), | 125 | 41.8 |

| Valsalva ratio: (<1.2), (N = 284)* | 52 | 18.3 |

| Postural hypotension | 52 | 17.4 |

| Diastolic BP response to sustained hand grip (<15 mmHg) | 108 | 36.1 |

HRV: Heart rate variability; E/I: Expiration to inspiration ratio.

* Sample size is less by 15 participants who had proliferative retinopathy and were excluded from the valsalva maneuver.

Figure 2.

Graph showing variation of prevalence of CAN by severity with age.

Participants with CAN had a significantly longer duration of diabetes (p < 0.001), higher waist circumference (p = 0.025), higher systolic blood pressure (p < 0.001), higher diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.001) and higher resting pulse rate (p < 0.001) compared to those without CAN. The proportion of patients with history of palpitations (p < 0.001) and numbness in feet (p = 0.024) was significantly more among participants with CAN compared to others. The mean pulse pressure, mean arterial pressure and QTc interval were significantly higher in participants with CAN compared to those without CAN (p < 0.001).

In multivariable regression models, significant correlates of CAN were: age over 50 years (aOR 3.48, 95%CI 1.35–8.99, p = 0.010), duration of diabetes over 10 years (aOR 4.09, 95%CI 1.78-9.38, p = 0.001) and presence of diabetic retinopathy (aOR 2.25, 95%CI 1.16–4.34, p = 0.016), as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Demographic and clinical factors correlated with CAN.

| % CAN positive | Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n/N (%) | OR 95%CI | p value | aOR 95%CI | |

| Age category(years) | |||||

| <35 | 7/29 (24.1) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 35–50 | 39/86 (45.4) | 2.61 (1.01–6.75) | 0.048 | 2.10 (0.77-5.74) | 0.147 |

| 51–65 | 110/184 (59.8) | 4.67 (1.90–11.49) | 0.001 | 3.48 (1.35–8.99) | 0.010 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 34/91 (37.4) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Female | 122/208 (58.7) | 2.38 (1.43–3.95) | 0.001 | 1.85 (0.94-3.66) | 0.076 |

| Duration of diabetes in years | |||||

| <5years | 74/170 (43.5) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 5–9 years | 38/76 (50.0) | 1.30 (0.75–2.23) | 0.347 | 1.04 (0.58–1.88) | 0.893 |

| 10 years and above | 44/53 (83.0) | 6.34 (2.91–13.81) | <0.001 | 4.09 (1.78–9.38) | 0.001 |

| Fasting blood sugar category | |||||

| ≤7.0 mmol/L | 24/60 (40.0) | Ref | Ref | ||

| >7.0 mmol/L | 132/239 (55.2) | 1.85 (1.04–3.29) | 0.036 | 1.62 (0.86–3.04) | 0.135 |

| Blood pressure category | |||||

| ≤130/80 mmHg | 18/60 (30.0) | Ref | |||

| >130/80 mmHg | 105/168 (62.5) | 3.89 (2.06–7.33) | <0.001 | ||

| Waist circumference | |||||

| Normal fat distribution | 26/62 (41.9) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Moderate central fat distribution | 19/48 (39.6) | 0.91 (0.42–1.95) | 0.804 | 0.66 (0.28–1.55) | 0.339 |

| High central fat accumulation | 111/189 (58.7) | 1.97 (1.10–3.53) | 0.022 | 1.16 (0.53–2.52) | 0.709 |

| Retinopathy | |||||

| Absent | 106/231 (45.9) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Present | 50/68 (73.5) | 3.28 (1.80–5.95) | <0.001 | 2.25 (1.16–4.34) | 0.016 |

| History of Palpitations in past 6 months | |||||

| No | 63/150 (42.0) | Ref | |||

| Yes | 93/149 (62.4) | 2.29 (1.44–3.65) | <0.001 | ||

| Symptoms of distal peripheral neuropathy | |||||

| No | 51/116 (44.0) | Ref | |||

| Yes | 105/183 (57.4) | 1.72 (1.07–2.74) | 0.024 | ||

| Resting heart rate | |||||

| ≤85 beats/min | 102/227(44.9) | Ref | |||

| >85 beats/min | 54/72 (75.0) | 3.68 (2.03–6.66) | <0.001 | ||

| QTc interval | |||||

| ≤440 ms | 74/213 (34.7) | Ref | |||

| >440 ms | 82/86 (95.4) | 38.51 (13.58–109.21) | <0.001 | ||

aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; Ref: Reference Category; CI: Confidence interval; QTc: Heart rate corrected QT.

Discussion

In the study of ambulatory diabetic patients in Uganda, we identified a prevalence of CAN of 52.2% (95% CI 46.3–58.0%), on the basis of at least one or more abnormal cardiovascular autonomic reflex tests. In adjusted regression models, CAN was more common in those over 50, people with diabetes for over 10 years and those with diabetic retinopathy. Our results, which as far as we know are the first from the region, demonstrate a remarkably high rate of autonomic neuropathy in the East African region, and motivate an important need to better explore this preventable and morbid condition in this population.

The prevalence of CAN (52.2%) in our study is comparable with findings from several studies elsewhere in lower and middle-income countries (LMICs) that have reported values between 45% and 60% [35,36,37,38,39]. Much lower prevalence estimates of CAN were reported elsewhere, particularly in higher-income countries. For instance, prevalence estimates between 15–34% have more recently been reported in Germany, Canada, United States and England [40,41,42,43]. We suspect that the high prevalence of CAN reported in our study and others in LMICs is likely attributable to later diagnosis and poorer glycemic control in these study populations. The mean HbA1c for the study participants in the present study was 9.7% which was above the recommended target of <7.5% [44]. The variation in the prevalence also might be attributed to the different methodologies employed in the diagnosis and classification of CAN. In this study, we used cardiovascular autonomic reflex tests which are extensively used in research, and have become a reference standard for measurement of autonomic function [45], with high reported validity [46].

Both the duration of diabetes and diabetic complications such as retinopathy have also been reported as major correlates for CAN in several prior studies [7,13,15,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. This is believed to be due to the central role of chronic hyperglycemia in the pathogenesis of CAN and other micro-vascular complications. Although the mechanisms by which hyperglycemia predisposes to CAN are not completely understood [54], increased oxidative stress, accumulation of advanced glycosylated end products, accumulation of sorbitol, disruption of hexosamine and protein C kinase pathways are the metabolic factors implicated [46,55,56]. In contrast, we did not note a correlation between glycemic control and the presence of CAN in our study. We believe this is due to the lack of a sufficient proportion of participants with adequate glycemic control in this study. However, this could also be due to reverse causality where patients become more proactive in controlling their blood sugars after developing CAN and other diabetes-related complications. This can only be detected through longitudinal studies. Moreover, because of variability in glucose control, a single point estimate of HbA1c may not correlate with the degree of autonomic neuropathy [53]. However, longitudinal studies have shown that mean HbA1c correlates with future risk of diabetic autonomic neuropathy [50,57]. Therefore, our study builds on the increasing body of evidence suggesting that other means of determining the severity of diabetes, such as the Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA), may be superior predictors of autonomic neuropathy [36,58].

Finally, older age is also a recognized risk factor for CAN [37,49,59]. Several changes can occur in autonomic nervous system with advanced age [60]. These changes include: selective activation of the sympathetic nervous system [61] with concomitant increase in basal plasma noradrenaline concentrations [62] and altered adrenoceptor function with reduced sensitivity to adrenergic antagonists and agonists [63]. Thus, it is well established that the autonomic nervous system function deteriorates with aging [64]. Our study hence underscores the need for targeted screening of elderly diabetic patients for CAN, so as to modulate diabetes therapeutic targets aimed at delaying the development and/or progression of CAN. The correlation with QTc interval prolongation demonstrated in our study, substantiates the recognized increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events such as cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death in patients with diabetic CAN [48,65,66].

Overall, our findings have important clinical and public health implications. We observed that most participants with diabetic CAN (88/156: 56%) had early CAN. There is emerging epidemiological evidence suggesting that there is a possibility of reversal of cardiovascular denervation in the early stages of the disease [9,67]. Therefore, improving glycemic control, life style modifications and cardiovascular disease risk factors management could slow the progression of CAN or even reverse it in this population. The high burden of CAN detected in this study also confirms the importance for early and systematic screening for this complication among patients with diabetes.

Study Limitations

This study has some notable limitations. The study was conducted in one hospital and findings from the study may not be generalizable beyond the population of individuals in outpatient diabetes care in peri-urban Uganda. Additionally, the study was done in a regional referral hospital, and thus a referral bias may overestimate the prevalence seen in the community-based setting. That said, we excluded individuals with multi-morbidity, including known cardiovascular disease, and those >65 years old, to investigate the epidemiology of CAN in otherwise healthy individuals with diabetes. Many of our measures, including clinical history, alcohol and smoking use are self-reported, and susceptible to recall bias and social desirability bias. Another important limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study, limiting our ability to assign the time directionality of association between CAN risk correlates (e.g. retinopathy) and CAN itself. Finally, we also are unable to assess the clinical impact of CAN without longitudinal observation of those with and without CAN, which we hope to explore in future studies. Finally, our estimates of relationships between CAN and correlates are susceptible to residual confounding of additional factors which we might not have measured or included in our regression models.

Conclusion

We detected CAN in over half of individuals with diabetes attending an outpatient diabetes clinic in Uganda. Older age, longer duration of diabetes, and co-existence of retinopathy were key correlates of the condition. Generally, our data highlight the need for better recognition of CAN as a common complication in diabetes. We therefore recommend that screening for CAN should be considered as part of routine evaluation of diabetic individuals in ambulatory care given the high prevalence of CAN in this study population and the rising burden of diabetes. This study also emphasizes the need for better management of diabetes including improved glycemic control and regular screening for other micro-vascular complications of diabetes such as retinopathy in diabetic individuals with CAN.

Data Accessibility Statements

The datasets generated and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in the study, the staff and management of Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital who contributed in various ways towards the success of the study. We are very grateful to members of the Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) of Mbarara University Research Training Initiative (MURTI) for their technical input into the study. We also acknowledge Dr. Sam Ruvuma of the Ophthalmology Department of Mbarara University of Science and Technology for his technical support.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the Fogarty International Center and co-founding partners (NIH Common Fund, Office of Strategic Coordination, Office of the Director (OD/OSC/CF/NIH); Office of AIDS Research, Office of the Director (OAR/NIH); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH/NIH); and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS/NIH)) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43TW010128. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio, BMI: Body mass index, BP: Blood pressure, CAN: Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, CI: Confidence interval, ECG: Electrocardiogram, HbA1c: Glycosylated hemoglobin, HOMA: Homeostatic model assessment, HRV: Heart rate variability, IQR: Inter-quartile range, MET: Metabolic equivalent task, MRRH: Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, MUST: Mbarara University of Science and Technology, NPDR: Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, PDR: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy, PI: Postural Index, QTc: Heart rate corrected QT interval, SD: Standard deviation, TIDM: Type 1 diabetes mellitus, T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Ethics and Consent

The study was approved by the institutional ethics review board of Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST-REC). We also received clearance for the study from the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (UNCST) and from the Research Secretariat in the Office of the President of Uganda, in accordance with the national guidelines. All study participants provided written informed consent before recruitment and participation. Participants who could not write gave consent with a thumbprint.

Funding Information

This research was supported by the Fogarty International Center and co-founding partners (NIH Common Fund, Office of Strategic Coordination, Office of the Director (OD/OSC/CF/NIH); Office of AIDS Research, Office of the Director (OAR/NIH); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH/NIH); and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS/NIH)) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43TW010128. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

R.M., A.M., D.C.A., S.L.M., and M.S. conceived the study, contributed to discussion, and reviewed, edited and wrote the manuscript. R.T. and R.M. collected the data. G.K. and D.C.A. reviewed ECG recordings. R.M. and M.S. analyzed the data. T.K. performed direct ophthalmoscopy on study participants. R.M. is the guarantor of this research work and, as such, had full access to all the data for the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Organization WH. Global Report on Diabetes: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roglic G. WHO Global report on diabetes: A summary. International Journal of Noncommunicable Diseases. 2016; 1(1): 3 DOI: 10.4103/2468-8827.184853 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2010; 87(1): 4–14. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J. IDF diabetes atlas: Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2011; 94(3): 311–21. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herman WH. The Global Burden of Diabetes: An Overview. Diabetes Mellitus in Developing Countries and Underserved Communities Springer; 2017; 1–5. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-41559-8_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assah F, Mbanya JC. Diabetes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Diabetes Mellitus in Developing Countries and Underserved Communities Springer; 2017; 33–48. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-41559-8_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spallone V, Ziegler D, Freeman R, Bernardi L, Frontoni S, Pop-Busui R, et al. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: Clinical impact, assessment, diagnosis, and management. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2011; 27(7): 639–53. DOI: 10.1002/dmrr.1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tesfaye S, Boulton AJ, Dyck PJ, Freeman R, Horowitz M, Kempler P, et al. Diabetic neuropathies:Uupdate on definitions, diagnostic criteria, estimation of severity, and treatments. Diabetes Care. 2010; 33(10): 2285–93. DOI: 10.2337/dc10-1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balcıoğlu AS, Müderrisoğlu H. Diabetes and cardiac autonomic neuropathy: Clinical manifestations, cardiovascular consequences, diagnosis and treatment. World Journal of Diabetes. 2015; 6(1): 80. DOI: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i1.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pop-Busui R. What do we know and we do not know about cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in diabetes. Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research. 2012; 5(4): 463–78. DOI: 10.1007/s12265-012-9367-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewing DJ, Clarke BF. Autonomic neuropathy: its diagnosis and prognosis. Clinics in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1986; 15(4): 855–88. DOI: 10.1016/S0300-595X(86)80078-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewing DJ, Martyn CN, Young RJ, Clarke BF. The value of cardiovascular autonomic function tests: 10 years experience in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1985; 8(5): 491–8. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.8.5.491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valensi P, Paries J, Attali J, for Research FG. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in diabetic patients: influence of diabetes duration, obesity, and microangiopathic complications—the French multicenter study. Metabolism. 2003; 52(7): 815–20. DOI: 10.1016/S0026-0495(03)00095-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziegler D, Gries F, Mühlen H, Rathmann W, Spüler M, Lessmann F. Prevalence and clinical correlates of cardiovascular autonomic and peripheral diabetic neuropathy in patients attending diabetes centers. The Diacan Multicenter Study Group C. Diabete & Metabolisme. 1993; 19(1 Pt 2): 143–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vinik AI, Maser RE, Mitchell BD, Freeman R. Diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes are. 2003; 26(5): 1553–79. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Association AD. Physical activity/exercise and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004; 27(suppl 1): s58–s62. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.S58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maser RE, Mitchell BD, Vinik AI, Freeman R. The association between cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and mortality in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003; 26(6): 1895–901. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maser RE, Mitchell BD, Vinik AI, Freeman R. The association between cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and mortality in individuals with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2003; 26(6): 1895–901. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin J, Wang W, Zhu L, Gu T, Niu Q, Li P, et al. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is an independent risk factor for left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes. BioMed Research International. 2017; 2017 DOI: 10.1155/2017/3270617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howorka K, Pumprla J, Haber P, Koller-Strametz J, Mondrzyk J, Schabmann A. Effects of physical training on heart rate variability in diabetic patients with various degrees of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. Cardiovascular Research. 1997; 34(1): 206–14. DOI: 10.1016/S0008-6363(97)00040-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Organization WH. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia. Report of a WHO/IDF consultation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Association AD. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2012. Diabetes Care. 2012; 35: S11 DOI: 10.2337/dc12-s011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chamberlain JJ, Rhinehart AS, Shaefer CF, Neuman A. Diagnosis and management of diabetes: Synopsis of the 2016 American diabetes association standards of medical care in diabetes. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2016; 164(8): 542–52. DOI: 10.7326/M15-3016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003; 42(6): 1206–52. DOI: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Health NIo. Classification of overweight and obesity by BMI, waist circumference, and associated disease risks; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National CEPN. Third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002; 106(25): 3143 DOI: 10.1161/circ.106.25.3143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armstrong T, Bull F. Development of the world health organization global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ). Journal of Public Health. 2006; 14(2): 66–70. DOI: 10.1007/s10389-006-0024-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeppsson J-O, Kobold U, Barr J, Finke A, Hoelzel W, Hoshino T, et al. Approved IFCC reference method for the measurement of HbA1c in human blood. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory emdicine. 2002; 40(1): 78–89. DOI: 10.1515/CCLM.2002.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward D. Prolongation of the QT interval as an indicator of risk of a cardiac event. European Heart Journal. 1988; 9: 139–44. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/9.suppl_G.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahnve S. Correction of the QT interval for heart rate: Review of different formulas and the use of Bazett’s formula in myocardial infarction. American Heart Journal. 1985; 109(3): 568–74. DOI: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90564-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulton AJ, Vinik AI, Arezzo JC, Bril V, Feldman EL, Freeman R, et al. Diabetic neuropathies: A statement by the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 2005; 28(4): 956–62. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuehl M, Stevens MJ. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathies as complications of diabetes mellitus. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2012; 8(7): 405 DOI: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bellavere F, Bosello G, Fedele D, Cardone C, Ferri M. Diagnosis and management of diabetic autonomic neuropathy. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed). 1983; 287(6384): 61 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.287.6384.61-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jung C-H, Kim B-Y, Kim C-H, Kang S-K, Jung S-H, Mok J-O. Association of serum adipocytokine levels with cardiac autonomic neuropathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2012; 11(1): 24 DOI: 10.1186/1475-2840-11-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jyotsna VP, Singh AK, Deepak K, Sreenivas V. Progression of cardiac autonomic dysfunction in newly detected type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2010; 90(1): e5–e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khandelwal E, Jaryal AK, Deepak KK. Pattern and prevalence of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in diabetics visiting a tertiary care referral center in India. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011; 55(2): 119–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pappachan J, Sebastian J, Bino B, Jayaprakash K, Vijayakumar K, Sujathan P, et al. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in diabetes mellitus: prevalence, risk factors and utility of corrected QT interval in the ECG for its diagnosis. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2008; 84(990): 205–10. DOI: 10.1136/pgmj.2007.064048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gandhi AU, Patel HP, Patel SV, Kadam AY, Parmar VM. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in relation to cardiovascular reflex tests and QTc prolongation in diabetes mellitus. National Journal of Integrated Research in Medicine. 2017; 8(4). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eze C, Onwuekwe I, Ogunniyi A. The frequency and pattern of cardiac autonomic neuropathy (CAN) in type 2 DM patients in a diabetic clinic in Enugu south-east Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2013; 22(1): 24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaiswal M, Divers J, Urbina EM, Dabelea D, Bell RA, Pettitt DJ, et al. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in adolescents and young adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: The SEARCH for diabetes in youth cohort study. Pediatric Diabetes. 2018; 19(4): 680–9. DOI: 10.1111/pedi.12633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ratzmann KP, Raschke M, Gander I, Schimke E. Prevalence of peripheral and autonomic neuropathy in newly diagnosed type II (noninsulin-dependent) diabetes. Journal of Diabetic Complications. 1991; 5(1): 1–5. DOI: 10.1016/0891-6632(91)90002-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zoppini G, Cacciatori V, Raimondo D, Gemma M, Trombetta M, Dauriz M, et al. The prevalence of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in a cohort of patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: the Verona newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes study (VNDS). Diabetes Care. 2015: dc150081 DOI: 10.2337/dc15-0081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ziegler D, Dannehl K, Mühlen H, Spüler M, Gries F. Prevalence of cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction assessed by spectral analysis, vector analysis, and standard tests of heart rate variation and blood pressure responses at various stages of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetic Medicine. 1992; 9(9): 806–14. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1992.tb01898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Diabetes Association. Standards of edical care in diabetes—2016. Diabetes Care. 2016; 39: 39–46. DOI: 10.2337/dc16-S003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vinik AI, Erbas T, Casellini CM. Diabetic cardiac autonomic neuropathy, inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Journal of Diabetes Investigation. 2013; 4(1): 4–18. DOI: 10.1111/jdi.12042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rolim LCdSP, Sá JRd, Chacra AR, Dib SA. Diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy: risk factors, clinical impact and early diagnosis. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 2008; 90(4): e24–e32. DOI: 10.1590/S0066-782X2008000400014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fisher VL, Tahrani AA. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus: current perspectives. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Ttherapy. 2017; 10: 419 DOI: 10.2147/DMSO.S129797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vinik AI, Ziegler D. Diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. Circulation. 2007; 115(3): 387–97. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.634949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Refaie W. Assessment of cardiac autonomic neuropathy in long standing type 2 diabetic women. The Egyptian Heart Journal. 2014; 66(1): 63–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.ehj.2013.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ko S-H, Park S-A, Cho J-H, Song K-H, Yoon K-H, Cha B-Y, et al. Progression of cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes: A 7-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2008; 31(9): 1832–6. DOI: 10.2337/dc08-0682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang C-C, Lee J-J, Lin T-K, Tsai N-W, Huang C-R, Chen S-F, et al. Diabetic retinopathy is strongly predictive of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in type 2 diabetes. Journal of diabetes research. 2016; 2016 DOI: 10.1155/2016/6090749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krolewski AS, Barzilay J, Warram JH, Martin BC, Pfeifer M, Rand LI. Risk of early-onset proliferative retinopathy in IDDM is closely related to cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes. 1992; 41(4): 430–7. DOI: 10.2337/diab.41.4.430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pavy-Le Traon A, Fontaine S, Tap G, Guidolin B, Senard J-M, Hanaire H. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and other complications in type 1 diabetes. Clinical Autonomic Research. 2010; 20(3): 153–60. DOI: 10.1007/s10286-010-0062-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dimitropoulos G, Tahrani AA, Stevens MJ. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus. World Journal of Diabetes. 2014; 5(1): 17 DOI: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i1.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feldman EL, Nave K-A, Jensen TS, Bennett DL. New horizons in diabetic neuropathy: mechanisms, bioenergetics, and pain. Neuron. 2017; 93(6): 1296–313. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sugimoto K, Yasujima M, Yagihashi S. Role of advanced glycation end products in diabetic neuropathy. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2008; 14(10): 953–61. DOI: 10.2174/138161208784139774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larsen JR, Sjøholm H, Berg TJ, Sandvik L, Brekke M, Hanssen KF, et al. Eighteen years of fair glycemic control preserves cardiac autonomic function in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004; 27(4): 963–6. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.27.4.963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bonora E, Formentini G, Calcaterra F, Lombardi S, Marini F, Zenari L, et al. HOMA-estimated insulin resistance is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetic subjects: prospective data from the Verona Diabetes Complications Study. Diabetes Care. 2002; 25(7): 1135–41. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Witte D, Tesfaye S, Chaturvedi N, Eaton S, Kempler P, Fuller J, et al. Risk factors for cardiac autonomic neuropathy in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2005; 48(1): 164–71. DOI: 10.1007/s00125-004-1617-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Brien I, O’Hare P, Corrall R. Heart rate variability in healthy subjects: Effect of age and the derivation of normal ranges for tests of autonomic function. Heart. 1986; 55(4): 348–54. DOI: 10.1136/hrt.55.4.348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Esler M, Hastings J, Lambert G, Kaye D, Jennings G, Seals DR. The influence of aging on the human sympathetic nervous system and brain norepinephrine turnover. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2002; 282(3): R909–R16. DOI: 10.1152/ajpregu.00335.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ewing D, Campbell I, Murray A, Neilson J, Clarke B. Immediate heart-rate response to standing: simple test for autonomic neuropathy in diabetes. Br Med J. 1978; 1(6106): 145–7. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.1.6106.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rowe JW, Troen BR. Sympathetic nervous system and aging in man. Endocrine Reviews. 1980; 1(2): 167–79. DOI: 10.1210/edrv-1-2-167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bonnemeier H, Wiegand UK, Brandes A, Kluge N, Katus HA, Richardt G, et al. Circadian profile of cardiac autonomic nervous modulation in healthy subjects: differing effects of aging and gender on heart rate variability. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2003; 14(8): 791–9. DOI: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03078.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Valensi PE, Johnson NB, Maison-Blanche P, Extramania F, Motte G, Coumel P. Influence of cardiac autonomic neuropathy on heart rate dependence of ventricular repolarization in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2002; 25(5): 918–23. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ninkovic VM, Ninkovic SM, Miloradovic V, Stanojevic D, Babic M, Giga V, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for prolonged QT interval and QT dispersion in patients with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetologica. 2016; 53(5): 737–44. DOI: 10.1007/s00592-016-0864-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vinik AI, Casellini C, Parson HK, Colberg SR, Nevoret M-L. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: A predictor of cardiometabolic events. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2018; 12 DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on request.