Abstract

Previous research on stress and media use mainly concentrated on between-person effects. We add to this research field by additionally assessing within-person associations, assuming that experiencing more stress than usual goes along with more nomophobia (“no-mobile-phone phobia”) and more passive and active Facebook use than usual, cross-sectionally and over time, and by exploring potential age differences. We conducted a secondary analysis of three waves of a representative multi-wave survey of adult Dutch internet users (N = 861). Specifically, we used two subsamples: (1) smartphones users for the analyses on nomophobia (n = 600) and (2) Facebook users for the analyses on social media (n = 469). Employing random-intercept cross-lagged panel models, we found within-person correlations between nomophobia and stress at one time-point, but not over time. For the younger age group (18–39 years), more passive Facebook use than usual was associated with more stress than usual six months later, and more stress than usual was followed by less passive Facebook use six month later. There were no longitudinal relationships for active Facebook use across the different age groups. Methodological and theoretical implications are discussed.

Keywords: Smartphone use, Nomophobia, Facebook use, Stress coping, Within-person effects

Highlights

-

•

We study the relationships of nomophobia, Facebook use and stress over time.

-

•

Nomophobia and stress correlate on the within-person level at one time-point.

-

•

Passive Facebook use is associated with more stress over time for younger adults.

-

•

Stress relates to less passive Facebook use six months later for younger adults.

-

•

There are no longitudinal effects for nomophobia, active Facebook use, and stress.

1. Introduction

The relationship between smartphone use and experienced stress is now widely studied (Vahedi & Saiphoo, 2018). Most studies propose that smartphones cause stress, for example by leading to an extension of working hours and a constant communication pressure (Hsiao, Shu, & Huang, 2017; Hung, Chen, & Lin, 2014). However, first findings also point to the opposite direction of influence (Carolus et al., 2019): When people are exposed to a stressful situation, a smartphone can be the “first-aid-in-the-pocket” (Schneider, Rieger, Hopp, & Rothmund, 2018). Due to its multifunctionality and availability, the smartphone can be easily used to release emotions (Hoffner & Lee, 2015), to escape a stressful situation (Wang, Wang, Gaskin, & Wang, 2015), to find relevant information (van Ingen, Utz & Toepel, 2016) or to receive social support (Petrovčič, Fortunati, Vehovar, Kavčič, & Dolničar, 2015) whenever needed. Social network sites (SNS) such as Facebook are one of the most important services for these online coping mechanisms, since they provide access to friends, family and acquaintances who can offer different kinds of support as well as a feeling of connectedness (Braasch, 2018; Deters & Mehl, 2013; Frison & Eggermont, 2015; Meier, Meltzer, & Reinecke, 2018).

Smartphones and especially SNS seem to be coping tools which are often used, and people might rely on them when they are confronted with a stressful situation (Carolus et al., 2019). This reliance on the availability of smartphones, however, has also been associated with a problematic form of use: People were hypothesized to develop “nomophobia” (King et al., 2014). Nomophobia is an abbreviation for “no-mobile-phone-phobia” (Yildirim & Correia, 2015) and is defined as the “fear of being unable to use or being unreachable via one's mobile phone” (Argumosa-Villar, Boada-Grau, & Vigil-Colet, 2017, p. 128). Nomophobia is classified as a form of problematic smartphone usage behavior and, in recent years, interest in this phenomenon is growing (Argumosa-Villar et al., 2017). While other constructs of problematic usage behavior focus on compulsive use (e.g., Lee, Chang, Lin, & Cheng, 2014) or on negative social consequences of a high amount of phone use (e.g., Chen et al., 2017), nomophobia focuses on the dependence regarding the constant availability of resources provided through smartphones (e.g., access to information & communication applications, see Yildirim & Correia, 2015). Therefore, nomophobia provides a different resource-focused perspective on smartphone use, which is of particular interest from a coping perspective.

Albeit the omnipresence of media devices in everyday life, there are surprisingly few studies that have investigated the relationship of stress and media use from a coping perspective (Nabi, Torres, & Prestin, 2017). Additionally, one of the main current shortcomings of this research field is that most studies are cross-sectional and non-experimental (Elhai, Dvorak, Levine, & Hall, 2017; Vahedi & Saiphoo, 2018; Verduyn, Ybarra, Résibois, Jonides, & Kross, 2017). This results in two problems: First, cross-sectional data cannot address the direction of associations over time. Thus, it is not possible to say whether an increase in smartphone or SNS use precedes stress, whether it succeeds stress or both (Elhai et al., 2017; Vahedi & Saiphoo, 2018). To draw valid causal inferences, randomized experiments are mostly seen as the most appropriate design, because they ensure independence of predictor and outcome (Raudenbush, 2001). However, if one wants to study temporal dynamics over a longer time frame in a natural setting, randomized experiments are often difficult to implement and, if the treatment entails negative states, also ethically sensitive. Therefore, the assessment of predictors and outcomes at multiple time points is considered a way to approximate the direction of influence and to “improve the validity of causal inference in nonrandomized studies” (Raudenbush, 2001, p. 523). A second problem of cross-sectional research designs is that even at one time-point, this data cannot address any questions on the relative importance of within-person versus between-person associations. Between-person differences represent how people differ from each other, e.g. how the average stress level that person A usually reports differs from the average stress level that person B usually reports and how this difference relates to the usual media use of A and B. Within-person differences represent the differences in the reports of one person over time, e.g. the difference between the stress level of person A at one time-point and the stress level this person A usually reports and how this difference relates to deviances from usual media use of A. Regarding the research on stress and coping, the within-person associations are particularly important, since situational influences play a major role in coping processes (Lazarus, 1999). Until now, we still do not know whether people who generally report more stress also report more smartphone or SNS use and dependence or if people change their use of and dependence on media devices and applications, when they are exposed to more stress than they usually are.

In this paper, we aim at studying the relationships between stress and nomophobia (“no-mobile-phone phobia”), as well as stress and SNS use over time focusing on a coping perspective. We will address the current shortcomings of the literature with a secondary analysis of three-wave panel data from a Dutch representative, longitudinal survey. Our research focus will be two-fold: On the one hand, we will focus on the within-person associations between stress and nomophobia, assuming that experiencing more stress than usual goes along with more nomophobia than usual at the same time point and six months later. On the other hand, we will focus on SNS and analyze if passive and active SNS use changes, when experiencing more stress than usual at the same time-point and six months later. With the present study, we provide important insights into the research field of stress and media use by adding empirical findings that are based on longitudinal data and a broad sample (Frost & Rickwood, 2017; Vahedi & Saiphoo, 2018). This allows us to additionally examine and compare the effects between stress and media use across different age groups.

1.1. Stress, coping & media use

People experience stress when the demands of a situation exceed their resources (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). According to the transactional model of stress, in a primary appraisal people evaluate if the transaction between the demands of a situation and their resources is perceived as being stressful (Lazarus, 1990). In a second appraisal, the available coping options are assessed (Lazarus, 1999). Coping options include a wide range of different strategies or styles which can be categorized in different ways (Skinner, Edge, Altman, & Sherwood, 2003). Lazarus and Folkman (1984) differentiated between problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. While the first includes attempts to solve the stress-evoking problem, the latter describes persons’ attempts to manage the emotions that are provoked through stress. There has, however, been a wide range of other classifications of coping styles, for example, differentiating between escapism, the planning of actions, distraction, or social support (Skinner et al., 2003). Although research has often categorized some of these coping or regulation strategies as adaptive and some as maladaptive, recent reviews have concluded: “that the most efficacious use of self-regulatory strategies is likely to be one that is most flexible” (Bonanno & Burton, 2013, p. 593). Thus, regulatory flexibility is important, when it comes to stress coping (Bonanno & Burton, 2013).

In addition to the different coping strategies, there are also different avenues for accomplishing these strategies (Nabi et al., 2017). For escaping a stressful situation, one could, for example, start daydreaming (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989) or play a video game (Reinecke, 2009). One avenue to cope with a stressful situation, therefore, might be using media (Nabi et al., 2017). Following the assumption that coping is most effective when it is flexible, media devices that can be used in a flexible way might be particularly suitable tools for coping.

1.2. Stress, smartphone use, and nomophobia

A smartphone might be one of these tools that provide flexible options for coping. According to a study of the Pew Research Center, 77% of the American population own a smartphone (Pew Research Center, 2018). In the European Union in 2017, 63% of a representative sample used smartphones to access the Internet. The highest percentage of smartphone users (85%) was reported for the Netherlands (Eurostat, 2018a). Smartphones are widely used in Western Societies and as result of their portability, they play an important role in the everyday life of their users (de Reuver, Nikou, & Bouwman, 2016; Fortunati & Taipale, 2014).

Smartphones are very flexible in their use (Humphreys, Von Pape, & Karnowski, 2013). Accordingly, research has shown that people use a wide range of contents that can be accessed via smartphones, when they experience stress: This includes the use of games (Reinecke, 2009; Snodgrass et al., 2014), blogs (Chung & Kim, 2008; Watson, 2018) and SNS (Braasch, 2018; Meier et al., 2018) for emotion-focused coping. In addition, media applications accessible through smartphones, especially blogs (Chung, Yang, & Chen, 2014; Watson, 2018) and SNS (Braasch, 2018), have also been found to be tools for problem-focused coping. Finally, there are many studies showing that SNS (Braasch, 2018; Chung et al., 2014; Cohen & Richards, 2015; Frison & Eggermont, 2015; Nabi, Prestin, & So, 2013) as well as message boards and support groups (Coursaris & Liu, 2009; Flickinger et al., 2017) are widely used to seek social support. When comparing the prevalence of media-based coping to other coping strategies, Nabi et al. (2017) found that media use was described frequently, when participants referred to steps they took to manage stress in both a student (15%, ranked 5th) and in a patient (32%, ranked 4th) sample. Similarly, van Ingen, Utz, and Toepoel (2016) found that 57% of their representative sample of Dutch internet users reported to use the Internet for coping. This confirms that people use the Internet and their smartphones when they experience stress.

Relying on smartphones for coping, however, is not only associated with benefits. The compensatory use of smartphones and other media has been associated with a problematic use of these technologies (Elhai et al., 2017; Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). Because of a heavy reliance on their phones, it has been argued that people could develop nomophobia, the “fear of being unable to use or being unreachable via one's mobile phone” (Argumosa-Villar et al., 2017, p. 128). In a first systematic assessment of the concept, Yildirim and Correia (2015) identified four dimensions of nomophobia: “(1) not being able to communicate, (2) losing connectedness, (3) not being able to access information and (4) giving up convenience.” (p. 133). Nomophobia has been described as a situational phobia (King et al., 2014) or has been classified as a form of problematic smartphone use (Argumosa-Villar et al., 2017). In the present paper, we consider nomophobia as part of problematic smartphone use that, however, also captures situational within-person differences in smartphone dependence. Different than other concepts that are discussed in relation with problematic phone use such as smartphone addiction including dimensions like compulsive usage or functional impairment (e.g., Chen et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2014), each of the dimensions of nomophobia relates to the high amount of resources that can be easily accessed via smartphones. Having access to resources is a key aspect of experiencing stress and is the basis of many coping behaviors (e.g., Lazarus, 1999). Thus, it seems plausible that nomophobia should be higher in times of high stress, in which access to the resources accessible through smartphones are of particular importance.

Studies have previously associated nomophobia with stress: Nomophobic persons are assumed to experience more stress than non-nomophobic persons in situations, in which they do not have their phone with them (Tams, Legoux, & Léger, 2018). Although we think that this assumption is valid, the focus of the present paper lies on the vice versa effect that smartphones are relied upon for stress coping. A meta-analysis on the association between stress and smartphone use has shown a positive correlation between both constructs. However, no longitudinal study was included in the meta-analysis (Vahedi & Saiphoo, 2018). A recent longitudinal two-wave study only supported an effect of excessive smartphone use on stress four months later, when the moderating effect for self-disclosure was considered (Karsay, Schmuck, Matthes, & Stevic, 2019). Testing within-person effects requires a longitudinal study design as well as a suitable analytical approach (Curran & Bauer, 2011; Hamaker, Kuiper, & Grasman, 2015). To our knowledge, up to now, there is no study that assessed within-person effects of nomophobia in general as well as in association with stress. Given the research findings presented above, showing that smartphones are often used for stress coping, we assume that experiencing stress might be related with a higher fear of not being able to use the smartphone at a specific time-point:

H1

People who experience more stress than usual show more nomophobia than usual.

We further assume that perceiving more stress than usual also results in a higher level of nomophobia over a longer period. A sustaining relationship could imply a learning effect, as assumed by Snodgrass et al. (2014) for games. They assumed that multiplayer online games are an effective tool for stress coping by providing an effective escape experience. However, due to this effectiveness, people might start relying on games too heavily and use other effective coping options less often. Consequently, their use could become problematic. Supporting this argumentation, regulatory flexibility was already shown to be negatively related to internet addiction (Cheng, Sun, & Mak, 2015). This might also be the case here: smartphones are flexible tools for coping and could, therefore, be very effective in reducing stress. This effectiveness could, however, result in a higher fear of having no phone to cope with stress, making the smartphone a tool that provides regulatory flexibility, but at the same time diminishes this flexibility by evoking a problematic dependency.

When assessing longitudinal relationships between two or more variables, the size of the time lag is very important, since a time lag that is too short or too long might mask effects. However, most theoretical conceptualizations lack precise specifications about suitable time lags between a probable cause and a probable effect (Mitchell & James, 2001). A look at prior studies on stress and smartphone use shows that there is a wide variation in the assessment of time frames, ranging from measurement without a specification (e.g., Harwood, Dooley, Scott, & Joiner, 2014; Jeong, Kim, Yum, & Hwang, 2016), times frames relating to a typical day (e.g., Haug et al., 2015), the last month (Coccia & Darling, 2014; Haug et al., 2015; Samaha & Hawi, 2016; Wang et al., 2015), the last six months (Murdock, Gorman, & Robbins, 2015), or the last year (Chiu, 2014, Thomée, Härenstam, & Hagberg, 2011). Positive associations between stress and smartphone use found for both, studies using time frames regarding the last month and the last year, indicate a positive relationship for different time frames. In our study, we referred to secondary data that used a time frame of six-months. We thus asked the following research question:

RQ1

: Does experiencing more stress than usual lead to more nomophobia than usual six months later?

1.3. Stress & SNS use

SNS are one of the media applications that are most widely studied in association with stress coping (e.g., Braasch, 2018). In the European Union, 54% percent indicated to participate in SNS. In the Netherlands, the user number amounts to 74% (Eurostat, 2018b). In the present study, we will explicitly focus on Facebook, since Facebook was at the time of data collection and still is the most popular SNS in the Dutch population (Statista, 2019).

Like smartphones, SNS can be used for the purpose of coping in a flexible way. In a study on online coping, the time spent on SNS was associated with all three assessed categories of coping: disengagement, problem-focused coping and socioemotional coping, with the first and third category showing higher associations than problem-focused coping (van Ingen et al., 2016). Similarly, other studies found that SNS are especially important tools in offering access to social support (Braasch, 2018; Frison & Eggermont, 2015; Nabi et al., 2013), but also were used for emotion-focused coping (Braasch, 2018; Meier et al., 2018) and problem-focused coping (Braasch, 2018). We, therefore, conclude that SNS are used for stress coping, while being especially suitable for obtaining social support and emotion-focused coping (see also Sriwilai & Charoensukmongkol, 2016).

As in the case of nomophobia, SNS use was found to be associated with stress by a few studies. In a survey study, Chen and Lee (2013) found positive associations between Facebook interaction and psychological distress. In a survey study by Frison and Eggermont (2015), daily stress was also positively associated with social support seeking on Facebook. Similarly, Brailovskaia, Rohmann, Bierhoff, Schillack, and Margraf (2019) and Brailovskaia, Velten, and Margaf (2019) found positive relationships between the intensity of Facebook use, a measure of “Facebook Addiction disorder” and daily stress in cross-sectional survey studies. In a two-wave longitudinal study, daily stress measured in the first wave predicted the measure of “Facebook Addiction Disorder” in the second wave (Brailskovskaia, Teismann, and Margraf, 2018) and These survey studies did not provide a differentiation between within- and between-person effects but confirm positive associations between different measures of Facebook use and stress cross-sectionally as well as over time.

Some studies studying SNS can also provide first insights about possible within-person relationships between SNS use and stress. In a qualitative study, Braasch (2018) assessed if Facebook usage changes, when high school pupils, university students and teachers experienced stress. She found very different usage patterns among these groups: high school pupils and most teachers reported to use Facebook less, when experiencing stress while university students, in contrast, reported a higher amount of usage. The longitudinal study of van der Schuur, Baumgartner, and Sumter (2018) examined between-person as well as within-person associations of social media use (including SNS), social media stress and sleep disturbances. Social media stress, however, was assessed as a combination of emotional responses to social media use and social media dependency; this construct thus measured stress directly elicited by social media and not perceived stress in general, which is the focus of the present study.

Hints on the within-person link between stress and Facebook use could also be derived from two experience sampling studies that did not measure stress but assessed (negative) affect and Facebook use (Kross et al., 2013; Verduyn et al., 2015). According to Lazarus (1999), negative affect and stress should be linked. Kross et al. (2013) found that Facebook use did predicted negative affect, whereas negative affect did not predict Facebook use, which would speak against the use of Facebook for coping. Using a similar research design, Verduyn et al. (2015) found the same effects pattern, however, when they differentiated between active and passive Facebook use, the negative effect only emerged for passive use.

A differentiation between active and passive use has also been shown to be insightful in other studies (Verduyn et al., 2017). Active SNS use involves “activities that facilitate direct exchanges with others (e.g., posting status updates, commenting on posts)”. Passive use on the contrary, refers to “consuming information without direct exchanges (e.g., scrolling through news feeds, viewing posts”, see Verduyn et al., 2015, p. 480). Regarding coping, active and passive use might reflect different coping styles: Active use could be associated with actively approaching the stressor by looking for social support, while passive use might reflect an attempt to cope with the negative emotions of stress. For other constructs of well-being, the passive consumption of news on SNS and the active, mostly communicative use have been found to show different associations: While direct communication on SNS was positively related to social capital and negatively to loneliness, the opposite was found for the passive consumption of Facebook content (Burke, Marlow, & Lento, 2010, pp. 1909–1912). In another survey study, passive but not active use of SNS was found to be associated with depression (Escobar-Viera et al., 2018). Because of these findings, we differentiated between active and passive Facebook use in our study (for an overview see Verduyn et al., 2017). Except for the qualitative research of Braasch (2018), none of the previous studies looked at within-person effects between perceived stress and SNS use. We address this gap by asking the following research question:

RQ2: When people experience more stress than usual, do they use Facebook more frequently than usual in an active or passive way?

Again, we also assessed, if a possible effect sustains over a longer period. As already argued for smartphones, Facebook could equally be a flexible and effective avenue for coping, so that people start to rely on Facebook for a longer period of time. Again, from a theoretical perspective the time frames of this effect are hard to determine. The longitudinal study of van der Schuur et al. (2018) used a six-month time interval. Frison and Eggermont (2015) did not ask about a specific time frame but assessed several stressful events and the intention to turn to Facebook when experiencing stress. Chen and Lee (2013) asked about the last 30 days for both distress and Facebook usage. The longitudinal study of Brailovskaia, Teismann, and Margraf (2018) used a one-year interval and the stress measure of this research group always assessed stress in the last twelve months, while Facebook measures assessed behavior on typical days (see also Brailovskaia, Rohmann et al., 2019; Brailovskaia, Velten et al., 2019). The two experience sampling studies of Kross et al. (2013) and Verduyn et al. (2015) used intervals of approximately two and a half hours on average. Again, looking at previous research, the used time frames broadly vary.

In our secondary analysis, we referred to a six-months interval and asked the following:

RQ3: Does experiencing more stress than usual lead to a change in the frequency of active and/or passive usage of Facebook six months later?

1.4. Stress, media use, and age groups

The differences in stress-related Facebook use between high school pupils and university students reported by Braasch (2018) could be due to the different age of these participants. Social media usage patterns as well as smartphone use are still very different between age groups with younger participants being usually more active and using more features (Fortunati & Taipale, 2014; Smith & Anderson, 2018). Additionally, it has been shown that the use of communication applications was associated with well-being differently and through different pathways for different age groups (Chan, 2018; Stevic, Schmuck, Matthes, & Karsay, 2019). While for the younger age group (18–34 years), civic engagement mediated the effect between multimodal connectedness and well-being, this relationship was mediated by individual social capital for the middle age group (35–54 years). For the older age group (55+ years), positive affect was additionally shown to be a relevant mediator (see Chan, 2018). In another recent study, Stevic et al. (2019) found that passive smartphone use negatively predicted life satisfaction four months later for participants regardless of age, while communicative smartphone use was positively related with life satisfaction four months later only for participants older than 63. This implies that different age groups seem to rely on their smartphones for different reasons, an observation which might also transfer to the context of coping. Thus, it is possible that nomophobia and stress are related differently in different age groups. There are, however, almost no studies that have analyzed nomophobia in samples other than students or adolescents. Also, in research on SNS use the focus remains on younger age groups (Frost & Rickwood, 2017; Verduyn et al., 2017). We, therefore, additionally explored whether the associations addressed in H1 and RQs 1–3 differ according to the participants’ age.

R4: Are the results on stress and nomophobia (H1, RQ1) and on stress and Facebook use (RQ2, RQ3) age-invariant?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

This is a secondary analysis of data from a larger panel study in which a representative sample of adult Dutch internet users was followed over a period of four years (2013–2017). Every six months, participants received a survey on their social media use and various indicators of social capital (the data are freely available, see www.redeftiedata.eu for the complete list of variables, the original Dutch items as well as an English translation; Utz, 2017a; 2017b; 2017c). The sample is largely representative for Dutch adults with regards to sex, age, education level and urban/rural place of living. Participants were informed, recruited and compensated by a professional market research institute (for further information see Utz, 2016). The study was approved by the local ethical committee of the Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien Tübingen (for more information about the study also see also www.redeftiedata.eu).

We have preregistered the selection of waves, operationalization of our variables and planned analyses (see https://aspredicted.org/ax5j3.pdf). We used the data from waves 6 to 8, because only these waves included a nomophobia measure. In wave 6, 1330 respondents participated in the survey. Of these, 1019 also answered the questionnaire in wave 7, and 861 respondents again participated in wave 8. The panel respondents participating in all three focused waves were slightly more often males (53%) and more represented in higher age groups: 20% younger adults between 18 and 39 years, 47% middle-aged adults between 40 and 64 years, and 33% older adults over 65. For the current analyses, we used two subsamples: Respondents who owned a smartphone in waves 6, 7 and 8 (“smartphone users”; n = 600) and respondents who used Facebook as their favorite SNS for private purposes in all three waves (“Facebook users”; n = 469). There was a large overlap between both subsamples, since 80% of the Facebook users were also smartphone users. Looking at the smartphone subsample, there were slightly more males (56%), more users from the younger (26%) and middle age group (52%) and less users from the older age group (22%). In the Facebook subsample, there were slightly less males (49%) and again more users from the younger (24%) and middle age group (51%; compared to 25% older users). In the following sections, we will refer to the three waves as wave 1, 2 and 3 for more convenient reading.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Stress

Stress was measured with four items from the Perceived Stress Scale (see Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). Answer options ranged from 1 = never to 5 = very often. An example item is “How often have you felt nervous and stressed”. Respondents were asked to answer these questions for the last six months. As in another paper using data from waves 1 to 6, the fourth reverse-coded item showed low fit and needed to be excluded (Utz & Breuer, 2017). For both subsamples, confirmatory factor analyses confirmed measurement invariance over time, since constraining factor loadings of the items across time points did not significantly decrease the model fit (as suggested by Chen, 2007). The scale further showed an acceptable internal consistency in both subsamples across time (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Invariance & Indices of the Measures Across Time.

| Fit of the Constrained Modela |

Changes in Model Fitb |

Mean (SD) |

α |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Χ2 (p) | CFI | RMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| Smartphone users (n = 600) | |||||||||||

| Stress | 27.62 (.091) | .996 | .027 | .000 | .004 | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.4 (0.9) | .83 | .83 | .81 |

| Nomophobia | 607.36 (.000) | .967 | .051 | .001 | .001 | 2.0 (0.9) | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.0 (0.9) | .94 | .94 | .94 |

| Facebook users (n = 469) | |||||||||||

| Stress | 39.39 (.004) | .989 | .048 | .000 | .005 | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.4 (0.9) | .83 | .81 | .80 |

| Active FB use | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.1) | ||||||||

| Passive FB use | 3.8 (1.3) | 3.8 (1.3) | 3.9 (1.3) | ||||||||

Note: FB = Facebook; CFA = confirmatory factor analysis; CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; a = CFA model where item loadings were constrained to be equal across time; b = compared to CFA model where items loadings freely varied across time; according to Chen (2007), invariance can be assumed, when ΔCFI ≤ −0.010 & ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015.

2.2.2. Nomophobia

Nomophobia was exclusively measured among the subsample of smartphone users with eight items adopted from the scale by Yildirim and Correia (2015). The items included in the survey covered all four dimensions of the original scale with “losing connectedness” as most represented subscale. Answer options ranged from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree. Confirmatory factor analysis again confirmed measurement invariance over time, since we did not observe a significant decrease in model fit, when constraining the item loadings across time (see Table 1). The scale showed a high internal consistency (α = 0.94) across all three panel waves.

2.2.3. Facebook use

Respondents were asked whether they used Facebook or another SNS mainly for private purposes. Those who agreed (68%, 67%, 70% for the three waves, respectively) were asked to indicate which SNS they preferred. In the respective analyses, we only included participants who chose Facebook as favorite SNS for all three waves (n = 469).

To assess passive and active Facebook use, these respondents were asked to indicate how often they read/viewed posts of others and how often they posted themselves, respectively. Answer options were 1 = rarely, 2 = a few times a month, 3 = a few times a week, 4 = once a day and 5 = multiple times a day. Respondents of the Facebook subsample indicated to read posts almost daily (M (SD) = 3.8 (1.3) at T1), but to post only a few times a month (M (SD) = 1.9 (1.1) at T1). These numbers remained stable across time (see Table 1). The means and standard deviations for each of the three age groups separately for all three measures can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptives of Nomophobia & Facebook use among the Different Age Groups.

| T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-39 y. |

40-64 y. |

65+ y. |

18-39 y. |

40-64 y. |

65+ y. |

18-39 y. |

40-64 y. |

65+ y. |

|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Nomophobiaa | 2.3 (1.0)∗ | 1.9 (0.9)∗ | 1.7 (0.8)∗ | 2.4 (1.0)∗ | 2.0 (0.9)∗ | 1.7 (0.8)∗ | 2.3 (1.0)∗ | 2.0 (0.9)∗ | 1.7 (0.8)∗ |

| Active Facebook useb | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.0) |

| Passive Facebook useb | 4.2 (1.0)∗ | 3.8 (1.3)∗ | 3.3 (1.5)∗ | 4.2 (1.0)∗ | 3.9 (1.3)∗ | 3.4 (1.5)∗ | 4.3 (1.0)∗ | 3.9 (1.3)∗ | 3.5 (1.4)∗ |

Note:

∗ indicates a significant posthoc comparison with the other two age groups (p < .05).

refers to the subsample of smartphone users (n = 600).

refers to the subsample of Facebook users (n = 469).

2.2.4. Age

Age was not assessed as a continuous variable, but in categories. We classified participants as younger adults (18–39), middle-aged adults (40–64), and older adults (older than 64). As most of previous studies focus on adolescents, students and younger adults (see e.g., the mean ages of the studies in the meta-analysis of Vahedi & Saiphoo, 2018 or the frequency of student samples in the review of Elhai et al. (2017), this study adds to the literature in providing results about older individuals.

2.3. Data analysis

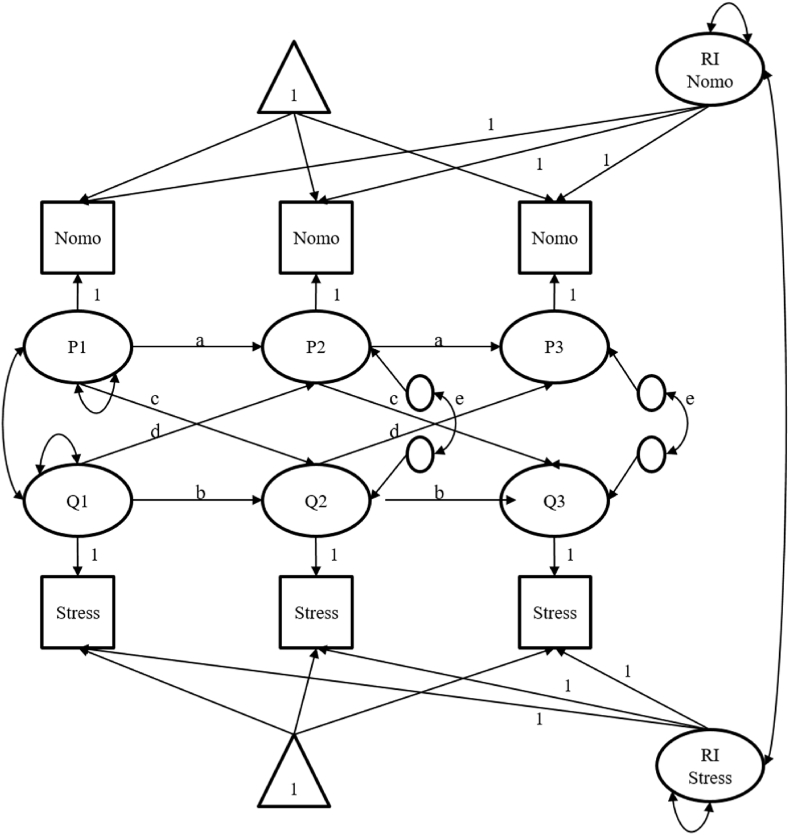

To analyze the dynamics between perceived stress and nomophobia as well as regular Facebook use, between-person and within-person variance needs to be differentiated, in order to clearly separate between time-invariant traits (between-person) and within-person dynamics (within-level). This can be achieved by using Random Intercept-Cross-Lagged Panel Models (RI-CLPMs) as suggested by Hamaker et al. (2015). In these models, time-invariant traits are extracted by adding a Random Intercept for each measure that represents the stability at the between-person level. Consequently, the remaining cross-lagged paths reflect the within-person dynamics that are not confounded by time-invariant traits (Hamaker et al., 2015). In the present study, we modelled three RI-CLPMs (stress-nomophobia; stress-active Facebook use; stress-passive Facebook use) as exemplified in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Exemplary illustrating the RI-CLPM for the variables of stress & nomophobia (Nomo) across the three panel waves. Note: Observed variables are represented by squares; latent variables at both, the between and the within-level, are constructed out of the observed variables (see ovals); 2 random intercepts (Stress & Nomo) indicate the between-person variances; 6 latent within-person variables (P1-P3; Q1-Q3) indicate the within-person variances; the within-person paths are indicated by the correlation between stress and nomo at T1, the residual correlations of stress and nomo at T2 & T3; 2 autoregressive paths for stress, 2 autoregressive paths for nomo and 4 cross-lagged paths between stress & nomo (each T1-T2 & T2-T3).

In each model, the two random intercepts across the three waves indicate the between-person variance, whereas the six within-person variables (variable 1 at T1-T3; variable 2 at T1-T3) indicate the within-person variance. The within-person paths are indicated by the correlation of the two variables at T11, the two autoregressive paths for variable 1, the two autoregressive paths for variable 2 and the four cross-lagged paths between variable 1 and 2 (each T1-T2 & T2-T3). We constrained the stability and the cross-lagged paths to be equal over time (from T1-T2 & from T2-T3). Due to the complexity of our models, using latent variables was not feasible for the variables stress and nomophobia. We thus decided to use mean indices for these measures following previous studies applying RI-CPLMs (see van der Schuur et al., 2018). For all three models, we used complete datasets based on a listwise deletion for the two subsamples (smartphone users only for stress and nomophobia & Facebook users only for stress and active respectively passive Facebook use).

We additionally investigated the moderating role of age applying multiple group comparisons between the three age groups for each RI-CLPMs. In order to proof measurement invariance between age groups, we followed a two-step procedure. First, we checked for configural invariance of the RI-CLPMs by ensuring acceptable fit values for the multigroup models (see Results). Since all factor loadings in RI-CLPMs are equally set to 1 anyway, constraining factor loadings between groups is not an appropriate way of testing measurement invariance for this type of models. We thus chose a different approach and tested equal loadings between age groups within the previous mentioned CFAs (see Measures) for our multi-item constructs stress and nomophobia. For the smartphone subsample, we did not observe a significant decrease in CFA model fit regarding stress and nomophobia, when constraining the factor loadings between age groups (stress: ΔCFI = −0.003; ΔRMSEA = 0.003; nomophobia: ΔCFI = −0.002; ΔRMSEA = −0.001). Similarly, there was no significant decrease regarding the constrained model fit, when looking at stress in the Facebook subsample (ΔCFI = −0.001; ΔRMSEA = −0.004; see Chen, 2007). We thus assume weak invariance between the three age groups for our central measures in both subsamples.

For all models, we used maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and Satorra-Bentler scaled test statistic (MLM). Global and specific fit indexes were indicated following the recommendations of Hu and Bentler (1999). All analyses were conducted using R and the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012). The syntax of our study, the dataset as well as a pdf including our R output can be found here: https://osf.io/cjqfu/?view_only=a7d6a9e4e920490fbd565d270dd26c69.

3. Results

3.1. Stress & nomophobia

To answer H1 and RQ1, we calculated a RI-CLPM focusing on individuals’ experienced stress and their level of nomophobia among the subsample of smartphone users (n = 600). This model showed good fit values: Χ2(5) = 2.87, p = .720, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.000. At the between-person level, we found a significant correlation between the random intercept factors of stress and nomophobia (r = 0.27, p < .001), implying that persons who reported higher levels of stress also indicated more nomophobia across the three waves. In line with our hypothesis H1, the findings moreover confirmed that people who experienced more stress than usual also showed more nomophobia than usual at T1 (r = 0.15, p = .044). Regarding the within-person levels over time, we did not find any significant cross-lagged path of stress on subsequent nomophobia or vice versa (see Table 2). Thus, answering our first research question, experiencing more stress than usual did not lead to more nomophobia than usual six months later.

3.2. Age differences

In RQ4, we argued that the relationship between stress and nomophobia might differ according to the respondents’ age. Since previous research mainly looked at adolescent and student samples, we were particularly interested in the relationship between stress and media use among adults. We therefore again ran the model with multigroup comparisons for three different age groups: Younger adults (18–39 y), middle-aged adults (40–64 y) and older adults (65+ y.). The constrained stability and cross-lagged paths over time were free to vary between the different age groups.

The multigroup model showed good fit values: Χ2 (15) = 15.58, p = .410, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.014. For the younger (r = 0.26, p = .006) and middle-aged adults (r = 0.26, p < .001), we could confirm an effect on the between-person level, indicating that those adults who reported higher levels of stress also reported experiencing more nomophobia across the three waves. This finding could not be confirmed for the older adults over 64 years (r = 0.11, p = .396). Post-hoc analyses (via confidence intervals) showed that the parameters did not significantly differ between the three age groups. This means that the association found in the two younger groups is significantly higher than zero, however we cannot say if this might also be true for the older age group. Looking at the within-person level, we did not find any effects of stress and nomophobia for the different age groups, neither cross-sectional nor over time (see Table 3).

Table 3.

The standardized relationships of stress and nomophobia within and between persons over time.

| Stress & Nomophobia |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

18-39 y. |

40-64 y. |

65+ y. |

|

| n = 600 | n = 158 | n = 313 | n = 129 | |

| Correlations | ||||

| Stress T1 ↔ Nomo T1 | .15∗ | .27 | .14 | .01 |

| RI-Stress ↔ RI-Nomo | .27∗∗ | .26∗∗ | .30∗∗ | .11 |

| Stability Paths | ||||

| Stress T1 → T2 | .10 | -.08 | .11 | .21 |

| Stress T2 → T3 | .09 | -.07 | .11 | .17 |

| Nomo T1 → T2 | .10 | -.01 | .09 | .16 |

| Nomo T2 → T3 | .13 | -.01 | .10 | .21 |

| Cross-Lagged Paths | ||||

| Stress T1 → Nomo T2 | .04 | -.16 | .09 | .15 |

| Stress T2 → Nomo T3 | .05 | -.18 | .09 | .17 |

| Nomo T1 → Stress T2 | .02 | -.19 | .14 | -.11 |

| Nomo T2 → Stress T3 | .02 | -.15 | .16 | -.11 |

Note: Base = subsample of smartphone users (n = 600); ∗∗ = p < .01, ∗ = p < .05; Nomo = Nomophobia; significant effects are marked bold.

3.3. Stress & facebook use

In a second step, to answer our second and third research question, we further analyzed the relationship of stress and Facebook use. For these analyses, we used the subsample of persons who indicated Facebook as their preferred SNS through all three waves (n = 469). Regarding Facebook use, we differentiated between posting as active use and reading posts as passive use. Regarding an active use, the RI-CLPM again showed good fit values: Χ2 (5) = 4.09, p = .537, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.000. The findings again confirmed a significant correlation of the random intercepts of stress and posting on Facebook (r = 0.19, p = .002), implying that persons who reported higher levels of stress also more actively used Facebook across the three waves. However, looking at the within-person level, we did not find any effects of stress and active Facebook use cross-sectionally and over time (see Table 4). The RI-CLPM for stress and passive Facebook use also showed good fit values: Χ2 (5) = 1.46, p = .918, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.000. However, the findings did not reveal any significant results, neither between persons (rRIs = 0.12, p = .058), nor at the within-person level. Thus, answering RQ2 and RQ3, for the total sample experiencing more stress than usual was not related to more active or passive Facebook use than usual cross-sectionally and over time (see Table 4).

Table 4.

The standardized relationships of stress and Facebook use within and between persons over time.

| Stress & Active FB Use |

Stress & Passive FB Use |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

18-39 y. |

40-64 y. |

65+ y. |

All |

18-39 y. |

40-64 y. |

65+ y. |

|

| n = 469 | n = 113 | n = 241 | n = 115 | n = 469 | n = 113 | n = 241 | n = 115 | |

| Correlations | ||||||||

| Stress T1 ↔ FB Use T1 | .09 | -.38 | .07 | .17 | -.05 | -.09 | .07 | -.18 |

| RI-Stress ↔ RI-FB Use | .19∗∗ | .38 | .25∗∗ | .02 | .12 | -.03 | -.01 | .24∗ |

| Stability Paths | ||||||||

| Stress T1 → T2 | .03 | .06 | .01 | .06 | .03 | -.03 | .04 | -.05 |

| Stress T2 → T3 | .02 | .13 | .01 | .04 | .03 | -.08 | .04 | -.02 |

| FB Use T1 → T2 | .12 | .44 | .18 | -.02 | .05 | .29 | .07 | .06 |

| FB Use T2 → T3 | .12 | .28 | .19 | -.02 | .05 | .28 | .08 | .07 |

| Cross-Lagged Paths | ||||||||

| Stress T1 → FB Use T2 | .01 | -.13 | -.02 | .10 | .04 | -.16∗ | .09 | .09 |

| Stress T2 → FB Use T3 | .01 | -.16 | -.02 | .08 | .04 | -.29∗ | .08 | .08 |

| FB Use T1 → Stress T2 | .11 | .10 | .07 | .18 | .11 | .37∗ | .16 | .02 |

| FB Use T2 → Stress T3 | .11 | .11 | .08 | .14 | .10 | .52∗ | .17 | .01 |

Note: Base = subsample of persons whose preferred SNS was Facebook (n = 469); FB = Facebook; ∗∗p < .01, ∗p < .05; significant effects are marked bold

3.4. Age differences

For both indicators, active and passive Facebook use, we also calculated models with multigroup comparisons regarding the three different age groups. Again, the constrained stability and cross-lagged paths over time were free to vary between the different age groups. The fit values for both models were good: active use Χ2 (15) = 10.12, p = .812, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.000; passive use Χ2 (15) = 14.86, p = .462, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.000. Regarding active Facebook use, we could confirm a significant correlation of the random intercepts only for the middle-aged adults between 40 and 64 years (r = 0.25, p = .002; see Table 4). Post-hoc analyses however again revealed that the parameters of the three groups did not significantly differ from each other.

Although there were no significant relationships between stress and passive Facebook use in the overall sample, we indeed found some relevant relationships in the age-separated models. First, we found a significant between-person effect for the oldest age group (r = 0.24, p = .028), implying that older adults who reported higher levels of stress also more intensively read Facebook posts across the three waves. Second, we detected significant within-dynamics of stress and passive Facebook use for the group of younger adults. The results showed that experiencing more stress than usual resulted in less reading of Facebook posts six months later (βT1-T2 = −0.16, p = .041; βT2-T3 = −0.29, p = .041). In contrast, more situational use of Facebook in a passive manner was associated with more stress than usual six months later (βT1-T2 = 0.37, p = .015; βT2-T3 = 0.52, p = .015). Again, the effects reported in this section did not significantly differ from the parameters of the other age groups.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that analyzes within-person relationships between stress and nomophobia as well as stress and active and passive Facebook use for different age groups from a coping perspective. We conducted a secondary analysis of a three-wave panel study with a representative Dutch sample. Our results revealed support for our first hypothesis that more nomophobia than usual is associated with more stress than usual at a specific time-point. We also found that individuals who generally reported more nomophobia across the three waves generally reported more stress than others. For nomophobia, the data showed no longitudinal associations over time. The effects regarding passive and active Facebook use revealed a complex picture, showing between-person effects only for some age groups and revealing interesting, albeit not predicted longitudinal within-effects between stress and passive Facebook use for the younger participants. We will now discuss the found effect patterns in more detail.

For nomophobia, supporting our hypothesis H1, the results showed that more stress than usual was associated with more nomophobia than usual at T1 (correlations at T2 & T3 represent error-correlations and should not be interpreted, see van der Schuur et al., 2018). Thus, when people are stressed their fear of not being able to use their smartphone at the same time seems to be high. We did not find such an effect for active or passive SNS use. There are two possible explanations for this pattern. First, smartphones offer access to a diverse range of coping possibilities and could therefore be a tool that provides regulatory flexibility. SNS are less flexible, since smartphones offer access to SNS as well as to numerous other possibilities. Thus, participants may rely on smartphones more heavily than on SNS for stress coping. A second explanation could be that measures of problematic use like nomophobia in general relate more to stress measures than measures of non-problematic use do. This was also confirmed by the meta-analysis of Vahedi and Saiphoo (2018): associations for stress and problematic phone use were generally larger than for stress and non-problematic phone use. It should be considered, though, that the within-person effect between nomophobia and stress was rather small and not robust across the different age groups.

Answering RQ1, we did not find any temporal dynamics between stress and nomophobia over time. Thus, we could not find a learning effect such that stress might also lead to a longer-lasting dependence on smartphones as suggested for games (see Snodgrass et al., 2014). On the other hand, the results did also not reveal stress-evoking effects of nomophobia for a time frame of six months.

On the between-person level, we found positive relationships between nomophobia and stress for the overall sample and for the younger and middle-aged adults when analyzed separately. Between-person correlations are associations that are relatively stable. This could imply that there are traits or other relatively stable variables that influence both, a higher perception of stress and a higher level of nomophobia. One of these variables could be a general tendency to cope ineffectively, since ineffective copers might use coping tools ineffectively and should experience a higher stress level (see LaRose, Lin, & Eastin, 2003, for a related consideration). Thus, ineffective copers may overuse some form of coping and, due to their omnipresence in everyday life, smartphones could be a popular form of such overuse. This explanation would not imply that smartphone use reduces coping flexibility for all users, but only for those who use it in a problematic way and report nomophobia. An alternative explanation might be that the effects are driven by lifestyle differences. Some people might be more mobile, which might expose them to more stressful situations and make it at the same time more necessary to depend on their smartphones.

For active and passive Facebook use, between-person effects revealed a more complex picture. Generally reporting more active Facebook use was only associated with a generally higher stress level for the middle-aged adults and generally reporting more passive Facebook use was only associated with a generally higher stress level for the older participants. This might not be in line with the explanation of unsuccessful copers as active use was found to be beneficial for well-being by previous studies (e.g., Verduyn et al., 2017). In contrast, the lifestyle explanation fits these results as well. Passive Facebook use is high among nearly all participants younger than 64 (see Table 2). Thus, we might have ceiling effects here and do not find effects for the younger respondents. Older participants who use Facebook at least passively, however, might also be older adults with a mobile lifestyle, which also includes more stress. Similarly for the middle-aged participants, using Facebook actively could be a sign of a mobile lifestyle. All in all, when considering the mobile lifestyle explanation it is important to keep in mind that SNS use might also be accessed via non-mobile devices and therefore might also be used in non-mobile situations, for example at home or at work.

An additional explanation for the found association between stress and active use for the middle-aged, but not for the younger adults could be that the two age groups differ in their support networks: Middle-aged adults might have a smaller offline support network. This explanation would fit with the results of Brailovskaia, Rohmann, et al. (2019) who found offline support to be a moderator of the association between stress and intensity of Facebook use.

On the within-person level, we found no effects for active and passive Facebook use among the two older age groups. However, regarding passive use we found interesting effects for the younger age group, albeit in the other direction than a coping perspective might imply: More passive Facebook use than usual was followed by more stress six months later and experiencing more stress than usual was followed by less passive Facebook use than usual. A possible explanation for both effects might be a successful self-regulation: Younger adults get stressed by passive Facebook use and, in a consequence, reduce their Facebook use. The effect of passive Facebook use on stress fits well with previous research supporting negative effects of passive SNS use on well-being among younger adults (e.g., Verduyn et al., 2017), also on the within-person level (Verduyn, Ybarra, Résbios, Jonides & Kross, 2015). A possible self-regulation implied by a reduction of passive Facebook use in response to higher stress is an interesting finding that adds to this research. This view is also supported by data collected by the Pew Research Center in 2018, suggesting that 42% of the participants said they have taken a break from checking Facebook in the last twelve months, which was also more likely among younger participants (Perrin, 2018).

Finally, our results need to be interpreted in the light of the limitations of the used data set. Secondary analyses have the advantage that data from longitudinal, representative studies can be used without the need to spend financial resources and without any further effort and data exposure for participants. However, they also entail the disadvantage that the operationalization might not always be fully suitable for the proposed research question (Greenhoot & Dowsett, 2012).

First, we want to emphasize that we only could test effects for a time-lag of six months. Considering the found relationship between nomophobia and stress at T1, effects of smartphones may be more situation-based and need shorter time lags. Passive Facebook use, on the other hand, may only have effects over the long run, since it might not cause stress to see the presumed perfect life of friends once, while it might cause stress to see the presumed perfect life of hundred friends repeatedly over a longer time (see Verduyn et al., 2017). It is important for future research to also look at other time lags in order to contribute to a more detailed and accurate picture of effects over time. This also is true for the time frames participants are asked to report upon. Previous studies used very different time frames to study the association of stress and media use. In our study, people were asked to report their stress level in general for the last six months. This might not be ideal for assessing within-person effects at one time-point. To shed light on the use of smartphones and SNS for coping, future studies especially need to assess shorter time lags as well as reports on shorter time frames.

Second, while our results shed light on temporal within-person dynamics between nomophobia, SNS use and stress, randomized experiments are needed to further test and understand the causal effects between smartphone and SNS use and stress. It might also be of value to add non-self-report data such as observations or physiological measures to assess stress as well as media use without the bias of self-reports.

Third, our findings did not show any significant differences between the age groups although we found that some effects were only significant for some of the age groups. Thus, we can support that the effect found in one group is significantly different from zero, however we cannot say if this might also be true for the other age groups. The reason for this might be the large range of our age groups, leading to heterogeneous groups of participants. Although it is important to look at representative and heterogeneous samples in order to detect population-wide effects, it is also of high importance to look at more homogenous samples to estimate more reliable relationships for specific (e.g., more vulnerable) persons.

5. Conclusion and practical implications

In the current paper, we aimed to examine the relationships between stress and nomophobia and SNS use from a stress coping perspective. All in all, our results revealed effects on different levels for different age groups and different media use types. Although we cannot give a clear answer to the question whether smartphones and SNS are good or bad for coping with stress, our findings show that it is important to compare different age groups as well as specific types of use and different time frames. This differentiated view on the uses and effects of digital media is also important when deriving practical implications. Our results suggest that results for certain groups, media types and types of use cannot be easily transferred to other groups or media types. In our study, more nomophobia, for example, was associated with a higher stress level at the same time point, while passive Facebook use was associated with more stress six months later for younger adults. These complex patterns imply very different effect mechanisms for the two different media use variables. Building on our findings, interventions that focus on the treatment of problematic media use should therefore be adapted to a specific target group and include a differentiated view that is not simply directed at reducing media use time regarding digital media or “the Internet” as a whole but addresses the way digital media is used.

Our results can open new avenues for further research on the conditions of a successful use of media devices. Particularly, our findings suggest that it is important to further assess within-person correlations of stress coping using shorter time frames, experimental studies and a situational measurement of media use and stress. Regarding between-person effects, personality traits and lifestyle differences that could influence both, stress and media use, need to be considered. For studying stress-evoking media use patterns like the passive use of Facebook, the implementation of self-regulation strategies might be an interesting area for future research.

Credit author statement

Lara N. Wolfers: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Project administration, Ruth Festl: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Sonja Utz: Methodology, Resources, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition

Data accessibility statement

All data are accessible at: https://www.redeftiedata.eu/.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors confirm that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007e2013)/ERC grant agreement no 312420.

Footnotes

To investigate the cross-sectional associations (see H1 & RQ2), we exclusively used the correlations of the latent variables at T1, since correlations at T2 and T3 represent residual correlations and might not be estimated reliably (see also van der Schuur et al., 2018)

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106339.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Argumosa-Villar L., Boada-Grau J., Vigil-Colet A. Exploratory investigation of theoretical predictors of nomophobia using the Mobile Phone Involvement Questionnaire (MPIQ) Journal of Adolescence. 2017;56:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno G.A., Burton C.L. Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science : A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science. 2013;8:591–612. doi: 10.1177/1745691613504116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braasch M. Springer; Wiesbaden, D: 2018. Stressbewältigung und social support in facebook: Der einfluss sozialer online-netzwerke auf die wahrnehmung und Bewältigung von Stress [stress coping and social support on facebook: The influence of social network sites on the perception of and the coping with stress. [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Rohmann E., Bierhoff H.-W., Schillack H., Margraf J. The relationship between daily stress, social support and Facebook Addiction Disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2019;276:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Teismann T., Margraf J. Physical activity mediates the association between daily stress and Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) – a longitudinal approach among German students. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;86:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Velten J., Margaf J. Relationship between daily stress, depression symptoms, and facebook addiction disorder in Germany and in the United States. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2019;22(9):610–614. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke M., Marlow C., Lento T. ystems. CHI ’10 Proceedings of the 28th international conference on Human factors in computing s. ACM; New York, NY: 2010. Social network activity and social well-being. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carolus A., Binder J.F., Muench R., Schmidt C., Schneider F., Buglass S.L. Smartphones as digital companions: Characterizing the relationship between users and their phones. New Media & Society. 2019;21:914–938. doi: 10.1177/1461444818817074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C.S., Scheier M.F., Weintraub J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan M. Digital communications and psychological well-being across the life span: Examining the intervening roles of social capital and civic engagement. Telematics and Informatics. 2018;35:1744–1754. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2018.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14(3):464–504. doi: 10.1080/10705510701301834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C., Sun P., Mak K.-K. Internet addiction and psychosocial maladjustment: Avoidant coping and coping inflexibility as psychological mechanisms. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2015;18:539–546. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Lee K.-H. Sharing, liking, commenting, and distressed? The pathway between facebook interaction and psychological distress. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16:728–734. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Zhang K.Z.K., Gong X., Zhao S.J., Lee M.K.O., Liang L. Examining the effects of motives and gender differences on smartphone addiction. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;75:891–902. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu S.-I. The relationship between life stress and smartphone addiction on Taiwanese university student: A mediation model of learning self-efficacy and social self-efficacy. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;34:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung D.S., Kim S. Blogging activity among cancer patients and their companions: Uses, gratifications, and predictors of outcomes. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2008;59:297–306. doi: 10.1002/asi.20751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T.-Y., Yang C.-Y., Chen M.-C. Online social support perceived by Facebook users and its effects on stress coping. European Journal of Economics Management. 2014;1:196–216. [Google Scholar]

- Coccia C., Darling C.A. Having the time of their life: College student stress, dating and satisfaction with life. Stress and Health. 2014;32(1):28–35. doi: 10.1002/smi.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Kamarck T., Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N., Richards J. ‘I didn't feel like I was alone anymore’: Evaluating self-organised employee coping practices conducted via Facebook. New Technology, Work and Employment. 2015;30:222–236. doi: 10.1111/ntwe.12051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coursaris C.K., Liu M. An analysis of social support exchanges in online HIV/AIDS self-help groups. Computers in Human Behavior. 2009;25:911–918. doi: 10.1016/J.CHB.2009.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curran P.J., Bauer D.J. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:583–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deters F.G., Mehl M.R. Does posting facebook status updates increase or decrease loneliness? An online social networking experiment. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2013;4:579–586. doi: 10.1177/1948550612469233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai J.D., Dvorak R.D., Levine J.C., Hall B.J. Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2017;207:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Viera C.G., Shensa A., Bowman N.D., Sidani J.E., Knight J., James A.E. Passive and active social media use and depressive symptoms among United States adults. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2018;21:437–443. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat Eurostat - data Explorer: Individuals - mobile internet access [statistic] 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-datasets/-/ISOC_CI_IM_I Retrieved from.

- Eurostat Eurostat - data explorer: Individuals - internet activities [statistic] 2018. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do Retrieved from.

- Flickinger T.E., DeBolt C., Waldman A.L., Reynolds G., Cohn W.F., Beach M.C. Social support in a virtual community: Analysis of a clinic-affiliated online support group for persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2017;21:3087–3099. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1587-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortunati L., Taipale S. The advanced use of mobile phones in five European countries. British Journal of Sociology. 2014;65:317–337. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frison E., Eggermont S. The impact of daily stress on adolescents' depressed mood: The role of social support seeking through Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;44:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R.L., Rickwood D.J. A systematic review of the mental health outcomes associated with Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;76:576–600. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhoot A.F., Dowsett C.J. Secondary data analysis: An important tool for addressing developmental questions. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2012;13:2–18. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2012.646613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaker E.L., Kuiper R.M., Grasman R.P.P.P. A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods. 2015;20:102–116. doi: 10.1037/a0038889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood J., Dooley J.J., Scott A.J., Joiner R. Constantly connected – the effects of smart-devices on mental health. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;34:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haug S., Castro R.P., Kwon M., Filler A., Kowatsch T., Schaub M.P. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2015;4:299–307. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffner C.A., Lee S. Mobile phone use, emotion regulation, and well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2015;18:411–416. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K.L., Shu Y., Huang T.C. Exploring the effect of compulsive social app usage on technostress and academic performance: Perspectives from personality traits. Telematics and Informatics. 2017;34:679–690. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.T., Bentler P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys L., Von Pape T., Karnowski V. Evolving mobile media: Uses and conceptualizations of the mobile internet. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2013;18:491–507. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hung W.H., Chen K., Lin C.P. Does the proactive personality mitigate the adverse effect of technostress on productivity in the mobile environment? Telematics and Informatics. 2014;32:143–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2014.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Ingen E., Utz S., Toepoel V. Online coping after negative life events: Measurement, prevalence, and relation with internet activities and well-being. Social Science Computer Review. 2016;34:511–529. doi: 10.1177/0894439315600322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S.-H., Kim H., Yum J.-Y., Hwang Y. What type of content are smartphone users addicted to?: SNS vs. games. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;54:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kardefelt-Winther D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;31:351–354. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karsay K., Schmuck D., Matthes J., Stevic A. Longitudinal effects of excessive smartphone use on stress and loneliness: The moderating role of self-disclosure. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2019;22:706–713. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A.L.S., Valença A.M., Silva A.C., Sancassiani F., Machado S., Nardi A.E. “Nomophobia”: Impact of cell phone use interfering with symptoms and emotions of individuals with panic disorder compared with a control group. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2014;10:28–35. doi: 10.2174/1745017901410010028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kross E., Verduyn P., Demiralp E., Park J., Lee D.S., Lin N.…Ybarra O. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PloS One. 2013;8(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRose R., Lin C.A., Eastin M.S. Unregulated Internet usage: Addiction, habit, or deficient self-regulation? Media Psychology. 2003;5:225–253. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0503_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S. Theory-based stress measurement. Psychological Inquiry. 1990;1:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S. Springer; New York, NY: 1999. Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S., Folkman S. Springer; New York, NY: 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.-K., Chang C.-T., Lin Y., Cheng Z.-H. The dark side of smartphone usage: Psychological traits, compulsive behavior and technostress. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;31:373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.-H., Chang L.-R., Lee Y.-H., Tseng H.-W., Kuo T.B.J., Chen S.-H. Development and validation of the smartphone addiction inventory (SPAI) PloS One. 2014;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier A., Meltzer C.E., Reinecke L. Coping with stress or losing control? Facebook-induced strains among emerging adults as a consequence of escapism versus procrastination. In: Kühne R., Baumgartner S.E., Koch T., Hofer M., editors. Youth and media. 2018. pp. 167–186. Baden-Baden, D: Nomos. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell T.R., James L.R. Building better theory: Time and the specification of when things happen. Academy of Management Review. 2001;26:530–547. doi: 10.5465/amr.2001.5393889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock K.K., Gorman S., Robbins M. Co-rumination via cellphone moderates the association of perceived interpersonal stress and psychosocial well-being in emerging adults. Journal of Adolescence. 2015;38:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabi R.L., Prestin A., So J. Facebook friends with (health) benefits? Exploring social network site use and perceptions of social support, stress, and well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16:721–727. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabi R.L., Torres D.P., Prestin A. Guilty pleasure no more: The relative importance of media use for coping with stress. Journal of Media Psychology. 2017;29:126–136. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin A. Pew Research Center; 2018. Americans are changing their relationship with Facebook.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/05/americans-are-changing-their-relationship-with-facebook/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovčič A., Fortunati L., Vehovar V., Kavčič M., Dolničar V. Mobile phone communication in social support networks of older adults in Slovenia. Telematics and Informatics. 2015;32:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2015.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center Demographics of mobile device ownership and adoption in the United States. 2018. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/ Retrieved on 13.08.19. Available from:

- Raudenbush S.W. Comparing personal trajectories and drawing causal inferences from longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:501–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke L. Games and recovery: The use of video and computer games to recuperate from stress and strain. Journal of Media Psychology. 2009;21:126–142. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105.21.3.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Reuver M., Nikou S., Bouwman H. Domestication of smartphones and mobile applications: A quantitative mixed-method study. Mobile Media & Communication. 2016;4:347–370. doi: 10.1177/2050157916649989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. [R package version 0.5-15] Journal of Statistical Software. 2012;48:1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samaha M., Hawi N.S. Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;57:321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F.M., Rieger D., Hopp F.A., Rothmund T. Paper presented at the 68th annual conference of the international communication association (ICA). Prague, Czech republic. 2018. First aid in the pocket—the psychosocial benefits of smartphones in self-threatening situations. [Google Scholar]

- van der Schuur W.A., Baumgartner S.E., Sumter S.R. Social media use, social media stress, and sleep: Examining cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships in adolescents. Health Communication. 2018;34(5):552–559. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1422101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner E.A., Edge K., Altman J., Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:216–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B.Y.A., Anderson M. Social media use in 2018. 2018. http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/ Retrieved from.

- Snodgrass J.G., Lacy M.G., Dengah F., Eisenhauer S., Batchelder G., Cookson R.J. A vacation from your mind: Problematic online gaming is a stress response. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;38:248–260. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sriwilai, Charoensukmongkol P. Face it, don't Facebook it: Impacts of social media addiction on mindfulness, coping strategies and the consequence on emotional exhaustion. Stress and Health. 2016;32:427–434. doi: 10.1002/smi.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statista Share of respondents using Facebook in The Netherlands from 2016 to 2018. 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/828836/facebook-penetration-rate-in-the-netherlands-by-age-group/ by age group [statistic]. Retrieved from.

- Stevic A., Schmuck D., Matthes J., Karsay K. ‘Age matters’: A panel study investigating the influence of communicative and passive smartphone use on well-being. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2019;12:1–15. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2019.1680732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tams S., Legoux R., Léger P.M. Smartphone withdrawal creates stress: A moderated mediation model of nomophobia, social threat, and phone withdrawal context. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;81:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]