Abstract

Introduction:

Autologous fat grafting (AFG) is a popular and effective method of breast reconstruction following mastectomy; however, the oncological safety of AFG remains in question. The purpose of this study is to determine if AFG increases the risk of cancer recurrence in the reconstructed breast.

Methods:

A matched, case-control study was conducted from 2000 to 2017 at the senior author’s institution. Inclusion was limited to female patients who underwent mastectomy and breast reconstruction with or without AFG. Data were further subdivided at the breast level. Chi-square analyses were used to test the association between AFG status and oncologic recurrence. A Cox proportional-hazards model was constructed to assess for possible differences in time to oncologic recurrence. The probability of recurrence was determined by Kaplan-Meier analyses and confirmed with log-rank testing.

Results:

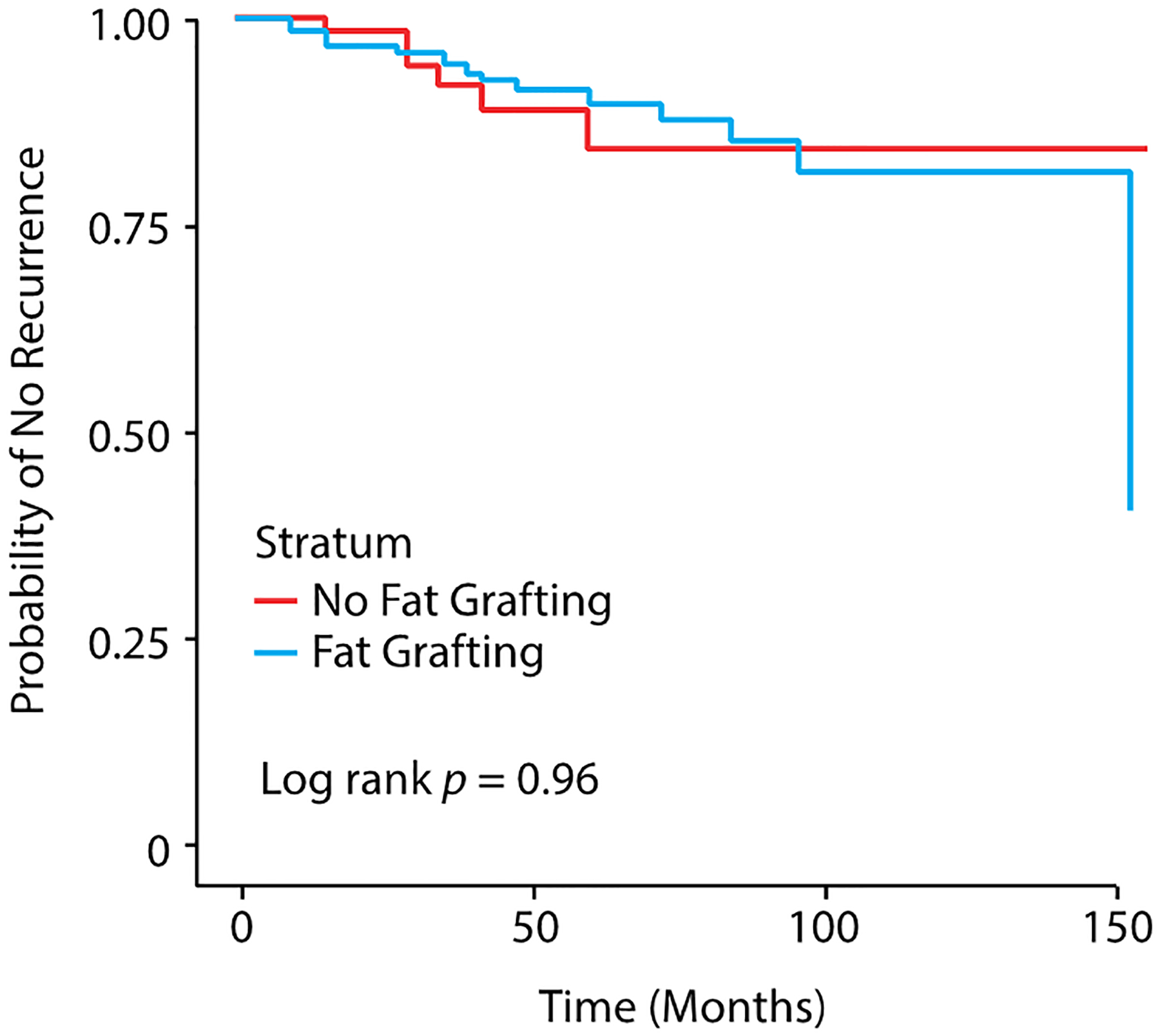

Overall, 428 breasts met study criteria. Of those, 116 breasts (27.1%) received AFG while 312 (72.9%) did not. No differences in the rates of oncologic recurrence were found between the groups (8.2% versus 9.0%; p < 1.000). Unadjusted (HR:1.03, CI: 0.41 – 2.60; p < 0.957) and adjusted hazard models showed no statistically significant increase in time to oncologic recurrence when comparing AFG to non-AFG. Additionally, no statistical differences in disease-free survival were found (p = 0.96 by log rank test).

Conclusion:

AFG for breast reconstruction is oncologically safe and does not increase the likelihood of oncologic recurrence. Larger studies (e.g. meta analyses) with longer follow-up are needed to further elucidate the long-term safety of AFG as a reconstructive adjunct.

Keywords: Autologous fat grafting, lipofilling, breast reconstruction, breast cancer recurrence

Introduction

Autologous fat grafting (AFG), commonly referred to as lipofilling, has become a popular and widely adopted surgical technique for restoration of volume and contour of the breast following oncologic resection.1–3 A 2013 survey of members of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons found that 62% of all respondents commonly used AFG for reconstructive breast surgery.4 The benefits of AFG are well documented and include the availability of multiple donor sites, low complication rates, improved aesthetic outcomes, and the ability to be performed in an ambulatory setting.5,6 AFG can be used to correct soft tissue deformities, mastectomy flap thinning, capsular contracture, and post-mastectomy pain syndrome. AFG has also been shown to improve skin quality in irradiated fields, which is important given the increasing use of breast conserving surgery and neoadjuvant radiation.7

Although popular, AFG has not always been viewed as an acceptable treatment option for breast reconstruction.8 This is due in part to preclinical studies demonstrating that adipose-derived stem cells can modulate the behavior of breast tumors in vitro and in animal models by cultivating a microenvironment favorable to proliferation of residual cancer cells through angiogenic factors, attenuation of the anti-tumor response, and the theoretical oncogenic potential of adipose-derived stem cells.9–14 Moreover, a single clinical study has demonstrated an increased risk of locoregional recurrence (LRR) with AFG following oncologic resection.15 While several studies have failed to demonstrate an increased risk of LRR,16,17 methodologic shortcomings and discordant basic science evidence has led many to continue to question the oncologic safety of AFG in breast reconstruction.

Scientifically speaking, the oncologic safety of AFG can only be determined through blinded, randomized controlled trials, but such trials would be fraught with challenges that would compromise the scientific rigor and may also be considered unethical. As such, pre-clinical investigations18–20 and well-designed observational studies may serve as the highest level of evidence for determining the oncologic risk of breast cancer recurrence. Moreover, the overwhelming majority of the scientific literature has focused on LRR at the patient, rather than the breast level. The breasts of a cancer patient can have quite different clinicopathologic characteristics with differing oncologic risk profiles. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine breast level oncologic outcomes of patients who have undergone AFG following mastectomy reconstruction. We hypothesize that there is no difference in rates of LRR or distant metastases (DM) when comparing reconstructed breasts that received AFG to those that did not.

Methods

In order to test our hypothesis, a retrospective, matched, case-control study was conducted from January 1, 2000 – August 21, 2017 at the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Kentucky. Waiver of informed consent was obtained.

Data Source

Inclusion was limited to female patients, ages 18 – 75 years who underwent mastectomy (prophylactic and/or therapeutic) and breast reconstruction with or without AFG that had at least 12 months of oncologic follow-up. Oncologic follow-up was defined as a clinical breast exam by either an oncologic surgeon or a reconstructive plastic surgeon. Patients receiving breast conserving surgery were excluded. Male patients account for less than 1% of all breast cancers and nearly 93% of men requiring mastectomy choose to forego breast reconstruction.21 Thus, they were excluded from the study.

Outcomes

Outcome variables of interest were abstracted from electronic medical records at the senior author’s institution. Data included patient age, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, asthma, anxiety, non-breast malignancy, depression, hypothyroid), smoking status (current, prior, none), American Joint Committee on Cancer pathologic stage (0 – 3), breast cancer histology type [invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC), intraductal carcinoma (IDC), ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS), mixed IDC and ILC, and unknown], mastectomy laterality (left, right, bilateral), prophylactic versus therapeutic resection type, hormone receptor positivity (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER-2NEU), BRCA gene mutation status (BRCA1, BRCA2, unspecified, unknown), radiation status (yes/no), receipt of chemotherapy, chemotherapy duration (days), receipt of hormone therapy (tamoxifen, anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane), receipt of immunotherapy (yes/no), locoregional recurrence of breast cancer (yes/no), time to locoregional recurrence (months), follow-up (months), distant metastasis of breast cancer recurrence (yes/no). Oncologic recurrence was defined as LRR or DM for therapeutic mastectomies and as a locoregional occurrence or a distant event for a prophylactic mastectomy. Prophylactic mastectomies included a combination of bilateral mastectomies for risk reduction and unilateral prophylactic mastectomy with contralateral therapeutic mastectomy. LRR was further defined as breast cancer recurrence on the ipsilateral chest wall or involving regional lymph nodes. The primary outcome of this study was LRR and secondary outcomes included DM.

Statistical Analysis

Cases (AFG) and controls (non-AFG) were matched at the patient level in a 1:3 ratio according to age (5-year increments), surgical service, American Society of Anesthesiology class, and wound class. Breast level data were stratified by AFG status and/or mastectomy status (therapeutic or prophylactic) and comparisons were made. For categorical variables, frequencies and column percentages were reported and p-values were calculated using chi-square. Continuous variables were tested for normality using Shapiro-Wilk normality tests and histograms. For normally distributed continuous variables, means and standard deviations were reported and p-values were calculated using t-tests. Otherwise, medians along with first and third quartiles were reported, and p-values were calculated using Mann-Whitney U tests. A Cox proportional-hazards model was constructed to assess for possible differences in time to recurrence. Covariates include patient age (1-year increase), pathologic stage, and fat grafting status. Time to breast cancer recurrence was reported in hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The probability of no recurrence was determined via Kaplan-Meier analysis and verified with log-rank testing. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Missing observations were reported and were excluded on a case-by-case basis. All analyses were completed using R programming language, Version 3.5.1. Kaplan-Meier analyses were performed using the R package survival, Version 2.42–6. Plots of Kaplan-Meier curves were created using the R package survminer, Version 0.4.3.

Lipofilling Technique

All AFG procedures were performed under general anesthesia. Fat was harvested manually using 30-cc or 60-cc syringes and suction cannulas. After harvest from the abdomen or flanks, fat was centrifuged with the resulting oil and serous components decanted. Processed fat was transferred to 3-cc syringes and injected using blunt infiltration cannulas, placing a small aliquot of fat with each withdrawal of the cannula. All surgeons’ (n = 5) techniques remained consistent throughout the study timeframe.

Results

Overall, 253 consecutive patients representing 428 breasts met study criteria and were included in the final analysis. Of those patients, 72 (28.5%) patients received AFG and accounted for 116 (27.1%) breasts, while 181 patients (71.5%) accounting for 312 (72.9%) breasts did not receive AFG.

Fat Grafting Volumes and Procedures

The mean total volume of fat grafting per patient was 97.9cc ± 87.9cc. The majority (74.1%) of patients received one AFG procedure, while 16.6% received two AFG procedures, and 9.3% received three or more AFG procedures. For patients who underwent autologous flap reconstruction, fat necrosis was not present in the reconstructed breast prior to AFG.

Therapeutic Mastectomy Patient Demographics and Case Characteristics

Therapeutic mastectomies were performed on 273 (63.7%) breasts. Of those, 73 (26.4%) breasts received AFG while 200 (73.6%) breasts did not. Demographics for breasts that received therapeutic mastectomy with or without AFG are summarized in Table 1. When comparing AFG to non-AFG breasts, the cohorts differed only in comorbid hyperlipidemia (p = 0.020). No significant differences were observed when comparing age, BMI, diabetes, smoking status, or other comorbidities between the groups.

Table 1:

Patient demographics for therapeutic and prophylactic mastectomies.

| Characteristic | Therapeutic Mastectomies* | Prophylactic Mastectomies** | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Autologous Fat Grafting | p | Overall | Autologous Fat Grafting | p | |||

| No AFG | AFG | No AFG | AFG | |||||

| Number of Mastectomies | 273 | 200 | 73 | 155 | 112 | 43 | ||

| Age (in years), Mean (SD) | 49.8 (9.1) | 50.2 (9.2) | 48.6 (8.8) | 0.182 | 47.5 (9.2) | 48.3 (9.3) | 45.3 (8.7) | 0.065 |

| BMI, Mean (SD) | 29.9 (7.4) | 30.0 (8.0) | 29.5 (5.5) | 0.651 | 30.7 (7.7) | 31.1 (8.3) | 29.8 (6.1) | 0.343 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 0.471 | 0.620 | ||||||

| No Smoking | 162 (59.6) | 115 (57.8) | 47 (64.4) | 95 (61.3) | 68 (58.9) | 29 (67.4) | ||

| Past Smoker | 52 (19.1) | 38 (19.1) | 14 (19.2) | 22 (14,2) | 17 (15.2) | 5 (11.6) | ||

| Current Smoker | 58 (21.3) | 46 (23.1) | 12 (16.4) | 38 (24.5) | 30 (25.9) | 9 (20.9) | ||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 181 (66.3) | 138 (69.0) | 43 (58.9) | 0.156 | 102 (65.8) | 82 (70.5) | 23 (53.5) | 0.070 |

| Diabetes | 31 (11.4) | 27 (13.5) | 4 (5.5) | 0.102 | 17 (11.0) | 14 (12.5) | 3 (7.0) | 0.402 |

| Hypertension | 96 (35.2) | 76 (38.0) | 20 (27.4) | 0.139 | 51 (32.9) | 44 (37.5) | 9 (20.9) | 0.076 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 54 (19.8) | 47 (23.5) | 7 (9.6) | 0.017† | 25 (16.1) | 21 (18.8) | 4 (9.3) | 0.235 |

| Asthma | 18 (6.6) | 15 (7.5) | 3 (4.1) | 0.416 | 11 (7.1) | 8 (7.1) | 3 (7.0) | 1.000 |

| Anxiety | 53 (19.4) | 35 (16.5) | 20 (27.4) | 0.065 | 39 (25.2) | 28 (23.2) | 13 (30.2) | 0.487 |

| Non-Breast Malignancy | 27 (9.9) | 22 (11.0) | 5 (6.8) | 0.431 | 12 (7.7) | 11 (9.8) | 1 (2.3) | 0.181 |

| Depression | 52 (19.0) | 36 (18.0) | 16 (21.9) | 0.579 | 29 (18.7) | 21 (18.8) | 8 (18.6) | 1.000 |

| Hypothyroid | 36 (13.2) | 28 (14.0) | 8 (11.0) | 0.649 | 14 (9.0) | 15 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.011† |

Statistically significant; Missing observations:

BMI n=11, Smoking n=1;

BMI n=4

Case characteristics for breasts that received therapeutic mastectomy with or without AFG are described in Table 2. Differences (p < 0.003) in BRCA status were observed when comparing breasts that received AFG to those that did not. Similarities were observed between groups in estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 status. Differences were also found with respect to histologic subtype (p < 0.0001) and pathologic stage (p < 0.038) (Table 3). Not surprisingly, radiation was more common in AFG breasts (27.4%) than non-AFG breasts (14.0%; p < 0.017). No differences were found with respect to hormone therapy or immunotherapy status.

Table 2:

Therapeutic mastectomies: BRCA and hormone receptor status.

| Autologous Fat Grafting Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | No AFG | AFG | p | |

| Number of Mastectomies | 273 | 200 | 73 | |

| BRCA Status, n (%) | 0.003† | |||

| Negative | 209 (76.8) | 151 (75.9) | 58 (79.5) | |

| BRCA1 | 16 (5.9) | 9 (4.4) | 7 (9.6) | |

| BRCA2 | 7 (2.6) | 7 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| BRCA Positive, Unspecified | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.1) | |

| Unknown | 37 (13.6) | 32 (16.1) | 5 (6.8) | |

| Estrogen Receptor Status, n (%) | 0.279 | |||

| Negative | 59 (21.6) | 43 (21.5) | 16 (21.9) | |

| Positive | 195 (71.4) | 146 (73.0) | 49 (67.1) | |

| Unknown | 19 (7.0) | 11 (5.5) | 8 (11.0) | |

| Progesterone Receptor Status, n (%) | 0.262 | |||

| Negative | 80 (29.3) | 58 (29.0) | 22 (30.1) | |

| Positive | 174 (63.7) | 131 (65.5) | 43 (58.9) | |

| Unknown | 19 (7.0) | 11 (5.5) | 8 (11.0) | |

| HER Status, n (%) | 0.365 | |||

| Negative | 213 (78.0) | 159 (79.5) | 54 (74.0) | |

| Positive | 37 (13.6) | 27 (13.5) | 10 (13.7) | |

| Unknown | 23 (8.4) | 14 (7.0) | 9 (12.3) | |

| Disease Laterality, n (%) | 0.022† | |||

| Right | 147 (53.8) | 114 (57.0) | 33 (45.2) | |

| Left | 114 (41.8) | 813 (40.5) | 33 (45.2) | |

| Bilateral | 12 (4.4) | 5 (2.5) | 7 (9.6) | |

Statistically significant, AFG = Autologous Fat Grafting, HER = human epidermal growth factor receptor. BRCA Status had 1 missing observation.

Table 3:

Therapeutic mastectomies: Surgical indication and breast cancer stage.

| Autologous Fat Grafting Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | No AFG | AFG | p | |

| Number of Mastectomies | 277 | 204 | 73 | |

| Histology Type, n (%) | 0.001† | |||

| Mixed IDC and ILC | 8 (2.9) | 8 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| LCIS | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ILC | 18 (6.6) | 9 (4.5) | 9 (12.3) | |

| IDC | 177 (64.8) | 138 (69.0) | 39 (53.4) | |

| DCIS | 56 (20.5) | 40 (20.0) | 16 (21.9) | |

| Unknown | 13 (4.8) | 4 (2.0) | 9 (12.3) | |

| Pathologic Stage, n (%) | 0.038† | |||

| 0 | 45 (16.5) | 33 (16.5) | 12 (16.4) | |

| 1 | 88 (32.2) | 72 (36.0) | 16 (21.9) | |

| 2 | 98 (35.9) | 69 (24.5) | 29 (39.7) | |

| 3 | 18 (6.6) | 14 (7.0) | 4 (5.5) | |

| Unknown | 24 (8.8) | 12 (6.0) | 12 (16.4) | |

Statistically significant, DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ; IDC = invasive ductal carcinoma; ILC = invasive lobular carcinoma; LCIS = lobular carcinoma in situ.

Prophylactic Mastectomy Patient Demographics and Case Characteristics

Prophylactic mastectomies were performed on 155 breasts (36.2%). Of those, 43 breasts (27.7%) underwent AFG while 112 breasts (72.3%) did not. Breast demographics for those that received prophylactic mastectomy with or without AFG are described in Table 1. When comparing AFG breasts to non-AFG breasts, the groups differed only with respect to comorbid hypothyroidism (0.0% versus 12.5%; p < 0.011). Non-significant differences were noted when comparing age, BMI, smoking status, or other comorbidities between the groups.

Case characteristics for breasts that received prophylactic mastectomy with or without AFG are described in Table 4. The prophylactic mastectomy cohort was relatively homogeneous, and differences were non-significant when comparing chemotherapy, hormone therapy type, immunotherapy status, or radiation status between AFG and non-AFG cases.

Table 4:

Medical therapy for therapeutic and prophylactic mastectomies.

| Characteristic | Therapeutic Mastectomies | Prophylactic Mastectomies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autologous Fat Grafting | Autologous Fat Grafting | |||||||

| Overall | No AFG | AFG | p | Overall | No AFG | AFG | p | |

| Number of Mastectomies | 273 | 200 | 73 | 155 | 112 | 43 | ||

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | 0.036† | 0.578 | ||||||

| Adjuvant | 124 (45.4) | 89 (44.5) | 35 (47.9) | 58 (37.4) | 43 (38.4) | 15 (34.9) | ||

| Neoadjuvant | 20 (7.3) | 15 (7.5) | 5 (6.8) | 17 (11.0) | 14 (12.5) | 3 (7.0) | ||

| None | 118 (43.2) | 92 (4546.0) | 26 (35.6) | 73 (47.1) | 51 (45.5) | 22 (51.2) | ||

| Unknown | 11 (4.0) | 4 (2.0) | 7 (9.6) | 7 (4.5) | 4 (3.6) | 3 (7.0) | ||

| Hormone Therapy, n (%) | 167 (61.2) | 127 (63.5) | 40 (54.8) | 0.244 | 79 (51.0) | 62 (55.4 | 17 (39.5) | 0.113 |

| Tamoxifen | 117 (42.9) | 88 (44.0) | 29 (39.7) | 0.622 | 59 (38.1) | 47 (42.0) | 12 (27.9) | 0.153 |

| Anastrozole | 43 (15.8) | 36 (18.0) | 7 (9.6) | 0.133 | 13 (8.4) | 11 (9.8) | 2 (4.7) | 0.518 |

| Letrozole | 20 (7.3) | 13 (6.5) | 7 (9.6) | 0.545 | 12 (7.7) | 8 (7.1 | 4 (9.3) | 0.739 |

| Exemestane | 15 (5.5) | 10 (5.0) | 5 (6.8) | 0.555 | 6 (3.9) | 5 (4.5) | 1 (2.3) | 1.000 |

| Raloxifene | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | ||||

| Lupron | 2 (0.7) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | ||||

| Immunotherapy, n (%) | 30 (11.0) | 22 (11.0) | 8 (11.0) | 1.000 | 14 (9.0) | 11 (9.8) | 3 (7.0) | 0.759 |

| Radiation, n (%) | 48 (17.6) | 28 (14.0) | 20 (27.4) | 0.017† | 24 (15.5) | 16 (14.3) | 8 (18.6) | 0.676 |

AFG is Not Associated with Risk of Oncologic Recurrence

Rates of LRR and DM for therapeutic mastectomies according to AFG status are summarized in Table 5. The rates of LRR were similar between AFG and non-AFG groups (8.2% versus 8.5%; p < 1.000). Additionally, oncologic recurrence of any type (LRR and DM) did not reveal differences between the cohorts (8.2% versus 9.0%; p < 1.000). Median time to recurrence was also similar between to AFG and non-AFG [31.5 months (IQR = 29.0 – 40.0) versus 37.0 months (IQR = 15.3 – 57.0); p < 0.973].

Table 5:

Oncologic recurrence among therapeutic mastectomies.

| Fat Grafting Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | No AFG | AFG | p | |

| Number of Mastectomies | 273 | 200 | 73 | |

| Any recurrence, n (%) | 24 (8.8) | 18 (9.0) | 6 (8.2) | 1.000 |

| Local Recurrence, n (%) | 23 (8.4) | 17 (8.5) | 6 (8.2) | 1.000 |

| Time to Recurrence, Months, Median [Q1,Q3] | 34.50 [15.8, 51.0] | 37.00 [15.3, 57.0] | 31.50 [29.00, 40.00] | 0.973 |

Briefly, the mean follow-up period for the sample was 47.6 ± 34.9 months while the median follow-up was 42.5 months (range, 20.8 – 63.0 months). A Kaplan-Meier curve showing the probability of oncologic recurrence stratified by AFG status is shown in Figure 1. No statistical differences in disease-free survival were found between the groups (p = 0.96 by log rank tests).

Figure 1:

Kaplan-Meier curve for time to recurrence stratified by fat grafting status and therapeutic/prophylactic status (n = 428 breasts).

AFG Does Not Interfere with Tumor Surveillance

The proportional hazards for time to LRR and DM for AFG and non-AFG patients are summarized in Table 6. Our unadjusted model failed to show a statistically significant increase in time to oncologic recurrence of any type for breasts undergoing therapeutic mastectomies when comparing those that received AFG to those that did not (HR: 1.03, CI: 0.41 – 2.60; p < 0.957). The adjusted model showed similar results.

Table 6:

Unadjusted and adjusted Cox-proportional hazards models assessing time to recurrence.

| Hazards Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Model | |||

| AFG (vs. none) | 1.026 | (0.41, 2.60) | 0.957 |

| Adjusted Model | |||

| Age (1-year increase) | 0.82 | (0.91,1.00) | 0.064 |

| Pathologic stage | |||

| Stage 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Stage 1 | 0.482 | (0.13, 1.81) | 0.279 |

| Stage 2 | 0.708 | (0.21, 2.40) | 0.574 |

| Stage 3 | 1.14 | (0.27, 4.90) | 0.861 |

| Unknown | 1.65 | (0.36, 7.52) | 0.517 |

| AFG (vs. none) | 0.807 | (0.31, 2.1) | 0.66 |

Discussion

AFG has become a widely adopted and effective method for reconstructive breast surgery.22 Despite its widespread adoption among reconstructive surgeons, AFG has not always been considered an acceptable treatment option for breast reconstruction. In 1987, the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons (ASPRS) advised against AFG due to concerns of potential adverse effects on breast imaging, specifically in screening for breast cancer and recurrence.23 In 2007, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (previously ASPRS) established a task force to assess indications, safety, and efficacy of AFG. They concluded that no reports existed to support an increased risk of malignancy and that AFG had the potential to interfere with breast cancer detection.24 The task force also determined that more research on the safety, efficacy, and the potential of fat grafting to interfere with breast cancer detection was needed. Since then, only one study has demonstrated an increased risk of tumor recurrence following oncologic resection.25 While several studies have shown that AFG is a safe option for breast reconstruction, concerns remain regarding the oncologic safety of the procedure. Additionally, the scientific literature has mainly focused on oncologic recurrence at the patient level while ignoring the clinicopathologic variance that may occur between two breasts in the same patient.

The present study sought to determine if AFG to the reconstructed breast increased the risk of oncologic recurrence. Consistent with the stated hypothesis, we found that AFG does not increase the risk of oncologic recurrence in the setting of breast reconstruction. The oncologic recurrence rates in our study coincide with the recurrence rates described in other clinical studies showing no difference in LRR rates between AFG and non-AFG groups.26–35 Additionally, the LRR rates for both groups fall within the reported range (5–10%) of breast cancer recurrence in the general population. These data also fall in line with recent in vitro work showing no increase in breast cancer cell growth in the presence of fat grafting.18

A recent Italian study is partly responsible for the continued debate regarding the oncologic safety of AFG. Petit et al. evaluated LRR and DM among 312 consecutive breast reconstruction patients receiving AFG matched to 612 controls that did not receive AFG. Subgroup analysis of 37 patients with intraepithelial neoplasia revealed an increased risk of local oncologic events (p < 0.001). However, these findings were not replicated in our study nor have they been reproduced in the literature. A likely explanation is that their observation is a result of random sampling error during the matching process. Nevertheless, these data strongly suggest that AFG does increase the risk of local oncologic events associated with AFG and breast reconstruction following extirpative therapy.

Myckatyn et al. conducted a multicenter, case-cohort study to investigate possible associations between AFG and time to breast cancer recurrence.26 Adjusting for covariates, their comprehensive review of 1,197 patients showed no difference in breast cancer recurrence. These data are consistent with our findings showing no statistically significant differences in the odds of LRR and DM between these cohorts. However, their patient level sample excluded patients with IDC breast cancer. While this aided in homogeneity of the sample, it limited the extrapolation of study results to other histologic subtypes. Our study includes all breast cancer histologic subtypes at the breast level, which strengthens the external validity of our results. A recent study by Kronowitz et al. found that LRR and systemic recurrence rates were not statistically significantly different when comparing patients who underwent AFG to those that did not.36 However, subgroup analysis revealed that patients receiving hormonal therapy had three times higher rates of LRR in those receiving AFG compared to controls. These findings were not replicated in our study.

Cohen et al. wisely considered breast level, rather than patient level characteristics when examining oncologic events associated with AFG and breast reconstruction.27 Their retrospective review of 829 breasts provided additional evidence that the rates of LRR and DM are similar between those receiving AFG and those that do not. However, Cohen and colleagues presented cohorts differing in terms of age, breast cancer histology type, and pathologic stage, with the therapeutic mastectomy plus AFG group being significantly younger than therapeutic mastectomy group alone.27 To account for these differences, they utilized a multivariate regression model and ultimately showed no differences when controlling for these variables. Our Cox regression model controlled for age and pathologic stage and also found no difference in time to oncologic recurrence between the AFG and non-AFG breasts. Cohen et al. also found that oncologic recurrence occurred later in the AFG group. This raises concerns about the ability of AFG to interfere with tumor surveillance. However, our adjusted and unadjusted proportional hazards models showed no difference in time to recurrence between the two groups. Importantly, these data provide additional scientific evidence and support the clinical opinion held by many reconstructive surgeons and scientists that AFG does not hinder tumor surveillance.

Limitations

Although this study has provided important evidence supporting the oncologic safety of AFG, several things should be taken into consideration when interpreting our single-center study. First, the study is retrospective in nature, the limitations of which have been previously described.37 This inherently limited the breadth of variables that could be explored, including Oncotype score and Ki-67 expression, which are both predictive of breast cancer recurrence. Secondly, differences in histologic subtype and pathologic stage existed between the cohorts, which could have affected our primary and secondary outcome data. The sample size in the present study limited the degrees of freedom and thus the inclusion of other important covariates (e.g. radiation status) into our proportional hazards model. Yet, it is important to note that Cohen et al. found that pathologic stage was not associated with an increase in breast cancer recurrence rates and that our hazards model controlled for some of these differences. Additionally, the median follow-up in our sample is less than 60 months. While the majority of breast cancer recurrence occurs within the first five years,38 it is possible that the rate of LRR or DM may have been higher if a longer follow-up period was achieved. This is currently being investigated by our group. Interestingly, Krastev et al. recently showed no difference in LRR at long-term follow-up.39 A large meta-analysis of nearly 4300 patients demonstrated a non-significant incidence rate difference in LRR of −0.15% per year between AFG and control groups, further justifying the safety profile of AFG in breast reconstructive surgery. However, the mean follow-up from AFG procedure was only 2.7 years for the included studies. There is certainly a risk of under-estimation in cumulative event incidence.

Lastly, patients receiving breast conserving surgery were not included in this study. As such, the results from our study cannot be extrapolated to this cohort; future work in this area is needed.

Conclusion

AFG is an oncologically safe method of breast reconstruction that does not increase the risk of oncologic recurrence and does not interfere with tumor surveillance. This study adds to the growing body of literature demonstrating the oncologic safety of AFG for patients considering this modality as a part of their breast cancer care. Larger studies (e.g. meta analyses) with longer follow-up periods are needed to further elucidate the long-term safety of this reconstructive procedure.9,40

Acknowledgements:

Dr. DeCoster is supported by a National Cancer Institute Surgeon-Scientist training grant (T32CA160003). This research was partially supported by the William S. Farish Endowed Chair in Plastic Surgery. The authors would like to thank the Markey Cancer Center’s Research Communications Office for assisting with the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no associations or financial disclosures to report that create a conflict of interest with the information presented in this article.

References

- 1.Khouri R, Del Vecchio D. Breast reconstruction and augmentation using pre-expansion and autologous fat transplantation. Clin Plast Surg. 2009;36(2):269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanchwala SK, Glatt BS, Conant EF, Bucky LP. Autologous fat grafting to the reconstructed breast: the management of acquired contour deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Losken A, Pinell XA, Sikoro K, Yezhelyev MV, Anderson E, Carlson GW. Autologous fat grafting in secondary breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66(5):518–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kling RE, Mehrara BJ, Pusic AL, et al. Trends in autologous fat grafting to the breast: a national survey of the american society of plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(1):35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groen JW, Negenborn VL, Twisk DJ, et al. Autologous fat grafting in onco-plastic breast reconstruction: A systematic review on oncological and radiological safety, complications, volume retention and patient/surgeon satisfaction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petit JY, Maisonneuve P, Rotmensz N, et al. Safety of Lipofilling in Patients with Breast Cancer. Clin Plast Surg. 2015;42(3):339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phulpin B, Gangloff P, Tran N, Bravetti P, Merlin JL, Dolivet G. Rehabilitation of irradiated head and neck tissues by autologous fat transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(4):1187–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vyas K. The Role of Fat Grafting and Adipose-Derived Stem Cells in Breast Reconstruction. Theses and Dissertations--Clinical and Translational Science 5 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lohsiriwat V, Curigliano G, Rietjens M, Goldhirsch A, Petit JY. Autologous fat transplantation in patients with breast cancer: “silencing” or “fueling” cancer recurrence? Breast. 2011;20(4):351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orbay H, Hinchcliff KM, Charvet HJ, Sahar DE. Fat Graft Safety after Oncologic Surgery: Addressing the Contradiction between In Vitro and Clinical Studies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142(6):1489–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manabe Y, Toda S, Miyazaki K, Sugihara H. Mature adipocytes, but not preadipocytes, promote the growth of breast carcinoma cells in collagen gel matrix culture through cancer-stromal cell interactions. J Pathol. 2003;201(2):221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaffler A, Scholmerich J, Buechler C. Mechanisms of disease: adipokines and breast cancer - endocrine and paracrine mechanisms that connect adiposity and breast cancer. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3(4):345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmerlin L, Donnenberg AD, Rubin JP, Basse P, Landreneau RJ, Donnenberg VS. Regenerative therapy and cancer: in vitro and in vivo studies of the interaction between adipose-derived stem cells and breast cancer cells from clinical isolates. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17(1–2):93–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearl RA, Leedham SJ, Pacifico MD. The safety of autologous fat transfer in breast cancer: lessons from stem cell biology. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(3):283–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petit JY, Rietjens M, Botteri E, et al. Evaluation of fat grafting safety in patients with intraepithelial neoplasia: a matched-cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(6):1479–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser JK, Hedrick MH, Cohen SR. Oncologic risks of autologous fat grafting to the breast. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31(1):68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaoutzanis C, Xin M, Ballard TN, et al. Autologous Fat Grafting After Breast Reconstruction in Postmastectomy Patients: Complications, Biopsy Rates, and Locoregional Cancer Recurrence Rates. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76(3):270–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva MMA, Kokai LE, Donnenberg VS, et al. Oncologic Safety of Fat Grafting for Autologous Breast Reconstruction in an Animal Model of Residual Breast Cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(1):103–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khouri RK Jr. Discussion: Oncologic Safety of Fat Graft for Autologous Breast Reconstruction in an Animal Model of Residual Breast Cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(1):113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuji W, Valentin JE, Marra KG, Donnenberg AD, Donnenberg VS, Rubin JP. An Animal Model of Local Breast Cancer Recurrence in the Setting of Autologous Fat Grafting for Breast Reconstruction. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2018;7(1):125–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Kalla T, Komorowska-Timek E. Breast total male breast reconstruction with fat grafting. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;2(11):e257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khouri K, Khouri JR, Khouri R. The Third Postmastectomy Reconstruction Option—Autologous Fat Transfer. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(1):63–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Report on autologous fat transplantation. ASPRS Ad-Hoc Committee on New Procedures, September 30, 1987. Plast Surg Nurs. 1987;7(4):140–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutowski KA, Force AFGT. Current applications and safety of autologous fat grafts: a report of the ASPS fat graft task force. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(1):272–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petit JY, Botteri E, Lohsiriwat V, et al. Locoregional recurrence risk after lipofilling in breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(3):582–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myckatyn TM, Wagner IJ, Mehrara BJ, et al. Cancer Risk after Fat Transfer: A Multicenter Case-Cohort Study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(1):11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen O, Lam G, Karp N, Choi M. Determining the Oncologic Safety of Autologous Fat Grafting as a Reconstructive Modality: An Institutional Review of Breast Cancer Recurrence Rates and Surgical Outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(3):382e–392e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krastev TK, Beugels J, Hommes J, Piatkowski A, Mathijssen I, van der Hulst R. Efficacy and Safety of Autologous Fat Transfer in Facial Reconstructive Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(5):351–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petit JY, Maisonneuve P, Rotmensz N, Bertolini F, Rietjens M. Fat Grafting after Invasive Breast Cancer: A Matched Case-Control Study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(6):1292–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva-Vergara C, Fontdevila J, Descarrega J, Burdio F, Yoon TS, Grande L. Oncological outcomes of lipofilling breast reconstruction: 195 consecutive cases and literature review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69(4):475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masia J, Bordoni D, Pons G, Liuzza C, Castagnetti F, Falco G. Oncological safety of breast cancer patients undergoing free-flap reconstruction and lipofilling. European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO). 2015;41(5):612–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rigotti G, Marchi A, Stringhini P, et al. Determining the oncological risk of autologous lipoaspirate grafting for post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34(4):475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krastev TK, Schop SJ, Hommes J, Piatkowski AA, Heuts EM, van der Hulst R. Meta-analysis of the oncological safety of autologous fat transfer after breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2018;105(9):1082–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gale KL, Rakha EA, Ball G, Tan VK, McCulley SJ, Macmillan RD. A case-controlled study of the oncologic safety of fat grafting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(5):1263–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva-Vergara C, Fontdevila J, Weshahy O, Yuste M, Descarrega J, Grande L. Breast Cancer Recurrence Is not Increased With Lipofilling Reconstruction: A Case-Controlled Study. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;79(3):243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kronowitz SJ, Mandujano CC, Liu J, et al. Lipofilling of the Breast Does Not Increase the Risk of Recurrence of Breast Cancer: A Matched Controlled Study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(2):385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song JW, Chung KC. Observational studies: cohort and case-control studies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(6):2234–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wangchinda P, Ithimakin S. Factors that predict recurrence later than 5 years after initial treatment in operable breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14(1):223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krastev T, van Turnhout A, Vriens E, Smits L, van der Hulst R. Long-term Follow-up of Autologous Fat Transfer vs Conventional Breast Reconstruction and Association With Cancer Relapse in Patients With Breast Cancer. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(1):56–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petit JY, Lohsiriwat V, Clough KB, et al. The oncologic outcome and immediate surgical complications of lipofilling in breast cancer patients: a multicenter study--Milan-Paris-Lyon experience of 646 lipofilling procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(2):341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]