Antiviral drugs have traditionally been developed by directly targeting essential viral components. However, this strategy often fails due to the rapid generation of drug-resistant viruses. Recent genome-wide approaches, such as those employing small interfering RNA (siRNA) or clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) or those using small molecule chemical inhibitors targeting the cellular “kinome,” have been used successfully to identify cellular factors that can support virus replication.

KEYWORDS: antiviral agents, host factors, drug resistance, epigenetic regulation, precision medicine

SUMMARY

Antiviral drugs have traditionally been developed by directly targeting essential viral components. However, this strategy often fails due to the rapid generation of drug-resistant viruses. Recent genome-wide approaches, such as those employing small interfering RNA (siRNA) or clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) or those using small molecule chemical inhibitors targeting the cellular “kinome,” have been used successfully to identify cellular factors that can support virus replication. Since some of these cellular factors are critical for virus replication, but are dispensable for the host, they can serve as novel targets for antiviral drug development. In addition, potentiation of immune responses, regulation of cytokine storms, and modulation of epigenetic changes upon virus infections are also feasible approaches to control infections. Because it is less likely that viruses will mutate to replace missing cellular functions, the chance of generating drug-resistant mutants with host-targeted inhibitor approaches is minimized. However, drug resistance against some host-directed agents can, in fact, occur under certain circumstances, such as long-term selection pressure of a host-directed antiviral agent that can allow the virus the opportunity to adapt to use an alternate host factor or to alter its affinity toward the target that confers resistance. This review describes novel approaches for antiviral drug development with a focus on host-directed therapies and the potential mechanisms that may account for the acquisition of antiviral drug resistance against host-directed agents.

INTRODUCTION

The recent report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV; 2019) listed 4,958 viral species across 14 orders, 143 families, and 846 genera (1). Recent advances in technology are uncovering new viruses and/or their genetic/antigenic variants almost on a daily basis. The world is currently experiencing an outbreak of a new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) (2–5), but fortunately most new viruses are not associated with clinical disease. Throughout human history, some new viruses have been the cause of major epidemics (6–15), and today’s highly interconnected world makes us even more vulnerable than in the past. Whereas the most successful approach to control any virus infection is with vaccines, this strategy is not effective for many agents for a variety of reasons. A potentially more effective general approach to combat virus infections is to develop effective antivirals (16). This approach was first used to control a herpesvirus infection and is currently the major means of controlling human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection (17). Recently, highly effective antivirals were also developed to control hepatitis C virus (HCV) (18–20), and the world would welcome antivirals active against COVID-19.

The majority of the antiviral drugs that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) act by directly targeting virus-encoded factors (21). However, these drugs almost invariably lose efficacy due to the emergence of drug-resistant virus variants (22–27). Consequently, alternative antiviral approaches need to be explored. In this review, we make the case for developing antiviral drugs that target host factors needed by the virus but not mandatory for host cell functions. We refer to such drugs as host-directed antiviral agents. Two major approaches, genome-wide small interfering RNA (siRNA) and/or clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) screens and small molecule chemical inhibitors targeting the cellular “kinome,” have revealed those of the cell’s ∼25,000 protein-encoding genes that interact and regulate replication of the infecting virus (28, 29). Some of these host factors are dispensable for the host but are required by the virus to complete various steps of its life cycle (30–35). These host factors can serve as targets for antiviral drug development (Fig. 1). Since genetic variability of the host is quite low compared to viruses, host-directed antiviral agents are less likely to become ineffective because of mutations in the viral genome (36, 37), although examples of resistance to such agents have been described (38, 39). The major goals of this review are to discuss novel approaches of antiviral drug development, with a focus on host-directed antiviral agents. We also discuss potential mechanisms of drug resistance against host-directed antiviral agents.

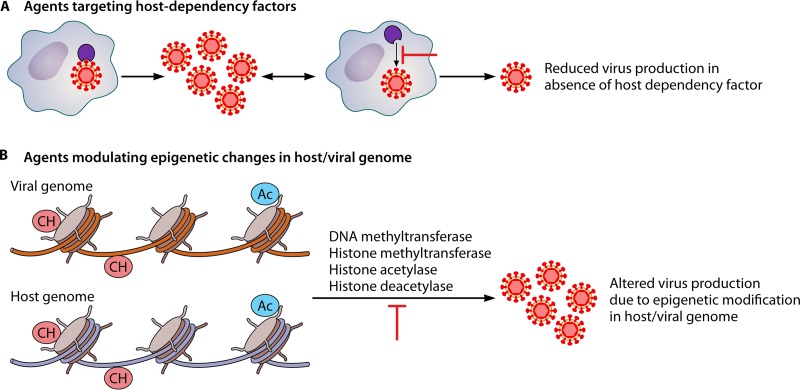

FIG 1.

Novel strategies of antiviral drug development. (A) In order to effectively replicate inside cells, virus is highly dependent on certain cellular factors, some of which are dispensable for cells and therefore may serve as targets for antiviral drug development. (B) Epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation and histone acetylation have also been shown to regulate viral replication/transcription/translation; thereby, inhibitors targeting the enzymes responsible for these epigenetic modifications (DNA methyltransferase, histone methyltransferase, histone acetylase, histone deacetylase) may serve as viable targets for antiviral drug development.

HOST-DIRECTED ANTIVIRAL AGENTS

Viruses establish numerous interactions with host factors and pathways during replication. In fact, technological advances have already identified several host factors that are essential for virus replication but dispensable for the host (40–42). Additionally, some host activities that respond to a viral infection, such as the interferon (IFN) and adaptive immune responses, can be manipulated to change the outcome of infection. Host-directed therapies have gained momentum in the past 2 decades. Many such studies are in the preclinical stages of development, with only a few compounds approved by the FDA. Herein we separately discuss FDA-approved drugs and therapeutic agents which are under preclinical development.

FDA-Approved Host-Directed Antiviral Agents

Of the majority of the antiviral drugs so far approved by the FDA, only a few are based on targeting host factors (Table 1) (21). Most of the FDA-approved host-directed antiviral drugs are based on IFNs and have been developed against chronic infections such as HIV-1, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) (21) (Table 1). There are several different subtypes of IFNs, but so far only alpha IFNs (IFNs-α) are being used clinically (43). The main target for IFN therapy initially was treatment of non-A non-B chronic hepatitis (now known to be hepatitis C) (44). IFNs were later approved to treat HBV (45) and HPV (46) infections as well. Subsequently, an increased sustained virological response rate of IFN therapy was achieved by various technological modifications and the inclusion of ribavirin. The modifications included conjugation with polyethylene glycol to form pegylated IFN (PegIFN), which prevented enzymatic degradation, increased the half-life of IFNs, and also decreased, but did not eliminate, side effects (47–49). However, this approach still has many problems, such as patient unresponsiveness (50) and production of interfering (anti-IFN) antibodies (51), and has been largely discarded in the United States since the development of other, safer drugs.

TABLE 1.

FDA-approved host-directed antiviral agentsa

| Trade name | Generic name | Target virus | Mechanism of action | Yr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intron A | IFN-α-2b | HPV | IFN mediated | 1988 |

| Alferon N injection | IFN-α-N3 | HPV | IFN mediated | 1989 |

| Condylox | Podofilox | HPV | Interrupts cell division cycle | 1990 |

| Intron A | IFN-α-2b | HCV | IFN mediated | 1991 |

| Intron A | IFN-α-2b | HBV | IFN mediated | 1992 |

| Infergen | Interferon alfacon-1 | HCV | IFN mediated | 1997 |

| Aldara | Imiquimod | HPV | Induction of cytokines | 1997 |

| Rebetron | PegIFN-α-2b plus ribavirin | HCV | IFN mediated | 1998 |

| Rebetol | Ribavirin | HCV | Multiple modes of action | 1998 |

| Pegintron/Sylatron | PegIFN-α-2b | HCV | IFN mediated | 2001 |

| Pegasys | PegIFN-α-2a | HCV | IFN mediated | 2002 |

| Pegasys | PegIFN-α-2a | HBV | IFN mediated | 2005 |

| Veregen | Sinecatechins | HPV | Immunomodulator | 2006 |

| Selzentry | Maraviroc | HIV-1 | Blocks gp120 and CCR5 interaction | 2007 |

IFN, interferon; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; HPV, human papillomavirus; PegIFN-α, pegylated IFN-α.

Currently, PegIFN-α-2b and ribavirin combination therapy is recommended for the treatment of chronic HCV infection, which results in sustained viral clearance in more than 50% of patients (52). However, the precise mechanism of action of IFN‐α and ribavirin against HCV is not well defined. In fact, viral infection itself may suppress IFN‐α induction and action in nonresponders, as has been observed in animal models of HCV infection (53). Moreover, individual host genetic factors, innate and adaptive immune responses, and viral genetic diversity as well as coinfections may also account for part of the nonresponse to therapy (54). Alfacon-1 (recombinant synthetic type I interferon) and ribavirin proved effective in some patients who did not respond to standard PegIFN-α/ribavirin therapy (44). Currently, new drug combinations are under development. For instance, telaprevir (an inhibitor of the HCV NS3/4 protease) in combination with PegIFN-α/ribavirin can be effective in treating chronic HCV patients who are unresponsive to conventional PegIFN-α/ribavirin therapy (55). Several other HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors used in combination with PegIFN-α and ribavirin may also achieve improved rates of a sustained virological response (56–59). However, the toxicity when they are combined with PegIFN-α and ribavirin still limits their overall efficacy (60, 61).

IFN preparations have several additional issues. These include fatigue, flu-like symptoms, neurological disorders, autoimmunity, ischemia, pneumonitis, anemia, neutropenia, nephritis, erythema, vasculitis, and necrosis, all of which limit their use (62–67). In addition, viruses resistant to IFN therapy have also been observed (68, 69); these may have emerged due to the acquisition of mutations in either structural or nonstructural proteins (70, 71).

In order to overcome the side effects of IFN therapy, targeting IFNs to local sites or preparing a prodrug formulation can be effective (72, 73). In this context, IFN-α-2 has been employed to target the liver with antibody specific to liver tissues (74, 75). Furthermore, to improve the pharmacokinetics and overcome pleiotropic effects, IFN-α-2b was engineered to make it latent by providing a protective shell of latency-associated protein of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) fused with HCV NS3 protease cleavage site as a linker (67).

Host-directed antiviral drugs have also been approved to treat HPV-associated warts. In this context, Intron A (IFN-α-2b), a drug also approved to treat HCV and HBV infection, has shown clinical efficacy against HPV-associated genital warts (76). Another drug, podofilox (Condylox) potently inhibits cell mitosis, which eventually results in the regression of HPV-associated warts (77). In addition, imiquimod (Aldara) exhibits profound antitumor (antiwart) activity by acting on several immunological activities (78). Likewise, sinecatechins (Veregen) was the first botanical drug product approved by the FDA in 2006 for the treatment of external genital and perianal warts, although its mechanism of action is as yet not known. Another injectable preparation of IFN-α-N3 upregulates major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) expression, which allows for enhanced presentation of virus-associated antigens, thereby activating cytotoxic CD8+ T cells that aid in wart regression (79).

Maraviroc, the only CCR5 antagonist licensed for clinical use, is a negative allosteric modulator of the C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5). Maraviroc inhibits HIV-1 entry by altering the extracellular loops of CCR5 in such a way that the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoproteins can no longer bind CCR5 (80, 81). In addition, maraviroc also reverses HIV-1 latency in vitro (82). However, HIV-1 strains with partial maraviroc resistance have appeared (83–85). The resistant strains may use alternate coreceptors (CXCR4 rather than CCR5) or alter their ability to bind the maraviroc-bound form of CCR5 (86–88).

Targeting Host Factors and Pathways Important for Viral Replication

Virus infection may activate intracellular signaling pathways, which regulate cell growth (37, 89–92), cell survival (37, 93), and/or immune activation (93, 94). In a typical course of virus infection, infected cells secrete IFNs, which induce nearby cells to express many so-called IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), whose functions include antiviral activity. Viruses may also usurp intracellular signaling pathways to their own advantage in the cells they infect (37, 93). For example, in influenza A virus (IAV) infection, the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway may be activated (95). This results in optimal synthesis of viral genomes, and it can also result in the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (95, 96). Thus, signaling pathways such as NF-κB may be targeted by therapies to regulate both virus replication and the virus-induced inflammatory responses.

Blockade of cellular receptors or other cellular proteins that regulate virus replication has also been targeted by therapies, but so far very few have entered into clinical trials (21). In the majority of studies, kinases and lipid synthases are the major host targets for antiviral drug development (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Host-directed antiviral agents under preclinical developmenta

| Host factor function | Antiviral agent(s) | Virus(es) | Host target | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support viral entry | DAS181 | IAV, PIV | Sialic acid receptor | 405–411 |

| R448, cabozantinib | ZIKV | AXL kinase | 412, 413 | |

| Ezetimibe | HCV | NPC1L1 | 166 | |

| Obatoclax, chloroquine, bafilomycin A1, ammonium chloride, Arbidol (umifenovir), chlorpromazine, niclosamide, mefloquine HCl | ZIKV, FLV hRhV, IAV | Regulation of endosomal pH | 413–417 | |

| Glycyrrhizin | IAV | Regulation of endocytotic uptake | 418 | |

| Concanamycin, saliphenylhalamide | IAV | Cellular vacuolar ATPases | 419, 420 | |

| Daptomycin | ZIKV | Modulation of late endosomal function | 417 | |

| LJ001 | IAV, poxvirus, FLV, HIV-1 | Modulation of membrane fluidity | 421 | |

| Thapsigargin | PPRV, NDV | SERCA | 39 | |

| Dynasore | HSV-1 | Dynamin | 422 | |

| MLS000394177, MLS000733230, MLS000730532 | EBOV | Macropinocytic uptake | 423 | |

| Bisindolylmaleimide I, calphostin C, chelerythrine, enzastaurin, staurosporine | WNV, IAV | PKC | 424, 425 | |

| Fattiviracin | HIV-1 | Internalization factors | 426 | |

| Aprotinin, camostat | IAV | Protease inhibitor | 427, 428 | |

| Jasplakinolide, cytochalasin D | hAdV | Actin polymerization | 429 | |

| Amiloride (EIPA) | CVB3, hAdV | Sodium-proton exchange | 430 | |

| Emetine, cephaeline | PPRV, NDV, BPXV, BHV-1, ZIKV, EBOV | Lysosomal function | 431, 432 | |

| Tenovin-1 | ZIKV | SirT1 and SirT2 | 433 | |

| Clonidine | IAV | α2-Adrenergic receptors | 434 | |

| Nanchangmycin | ZIKV | AXL kinase | 433 | |

| Erlotinib | HCV | EGFR and GAK | 104, 165 | |

| Sunitinib | HCV | AAK1 | 104 | |

| NIM-811, Debio-025 | EV | Cyclophilin | 435 | |

| STI-571, Gleevec, imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib | Poxvirus, PyV, HIV-1 | Abl family protein kinases | 436, 437 | |

| Support viral genome replication, transcription, and translation | SD-29 | HSV-1 | RACK1 | 438 |

| Torin1, rapamycin | CMV, BEFV | mTOR kinase | 439–441 | |

| Hippuristanol, silvestrol | CMV, ZIKV | eIF4A | 440, 442 | |

| CGP57380 | HSV-1, poxvirus, hCMV | MNK1 | 38, 443–445 | |

| 4E2RCat, 4EGI-1 | CoV, BPXV | eIF4E/eIF4G interaction | 38, 446 | |

| Apigenin | FMDV, EV71 | hnRNP A1 and A2 | 447, 448 | |

| AG879 | IAV, SV, HSV-1, MHV, RV | NGFR | 121, 129 | |

| Genistein | HIV-1 | Tyrosine kinase | 449 | |

| Tyrphostin A9 | IAV, SV, HSV-1, MHV, RV | PDGFR | 121, 129 | |

| Gefitinib (Iressa) | Poxvirus, hCMV | EGFR | 450, 451 | |

| Ivermectin | IAV | Importins | 452 | |

| Verdinexor, DP2392-E10, leptomycin B | IAV | XPO1 | 453–455 | |

| TG100572 | HSV-1 | Src family kinases | 156 | |

| Vemurafenib | IAV | Raf | 456 | |

| U0126, Cl-1040 (PD184352) | IAV, IBV, PEDV, AstV, BDV, CoV, JUNV, HSV-1 | MEK1/2 | 457–464 | |

| FR180204, Ag-126 | VEEV, DENV, lentivirus | ERK1/2 | 465, 466 | |

| SB203580 | EMCV | p38 | 467 | |

| AS601245, SP600125 | IAV, hCMV | JNK | 468, 469 | |

| Mycophenolic acid, ribavirin | ZIKV, IAV, RSV, CoV, EV71, CVB3, HCV | IMPDH | 417, 470–472 | |

| Leflunomide, compound A3 | FLV | DHODH | 368 | |

| TVB-2640 | HCV | FAS | 389, 473 | |

| Statins (atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin) | HCV | HMG-CoA reductase | 393 | |

| Clypearin, corilagin, TG003 | IAV | CLK1 | 474 | |

| Silvestrol, pateamine | IAV | eIF4A | 475, 476 | |

| Curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, bisdemethoxycurcumin, EF-24, FLLL32 | JEV, RVFV, HCV, EV71 | Ubiquitin-proteasome, PKC, NF-κB, Akt | 477–480 | |

| PIK93, BF738735, GW5074, T-00127-HEV1 | EV | PI4KB | 481, 482 | |

| Itraconazole, 25-hydroxycholesterol, AN-12-H5, T-00127-HEV2, TTP-8307 | EV | OSBP | 481 | |

| EYP001 | HBV | Synthetic farnesoid X receptor | 483 | |

| APG-1387 | HBV | cIAP2 | 484 | |

| Fenretinide (4-HPR) | ZIKV, DENV | Activator of retinoid receptors | 485 | |

| Difluoromethylornithine, diethylnorspermine | ZIKV, DENV | Host polyamine synthesis | 486 | |

| Cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) | hRSV | Intracellular calcium ATPase | 487 | |

| MK2206 | IAV | Akt | 488 | |

| PD-0332991 | HSV-1 | CDK4/6 | 489 | |

| LDC4297 | hCMV, AdV | CDK7 | 490 | |

| JMN3-003 | Myxovirus | G1-phase arrest | 369 | |

| AGK2 | HBV | SirT2 | 491 | |

| Amiloride (EIPA) | CVB3, hAdV35 | Sodium-proton exchange | 429, 430 | |

| HL05100P2, cyclosporine, NIM-811, CRV431, CMX157 | EAV, PRRSV, HCV, HBV | Cyclophilin | 435, 492, 493 | |

| Emetine | PPRV, NDV, BPXV, BHV-1 | Unknown | 431, 432 | |

| Cephaeline | ZIKV, EBOV | Unknown | 431, 432 | |

| Nitazoxanide, tizoxanide | ZIKV, RV, NV, HBV, HCV, IAV | Unknown | 494 | |

| Glycyrrhizin | CVB3, hAdV, IAV | Unknown | 418, 429, 430 | |

| RG7834 | HBV | Unknown | 495 | |

| Veregen (sinecatechins) | HPV | Unknown | 21 | |

| Support virus assembly and release | Brefeldin A | DENV, HCV | ADP-ribosylation factor | 496, 497 |

| PF4620110, LCQ908 | HCV | DGAT1 | 498 | |

| AG879 | IAV, SINV, HSV-1, MHV, RV | NGFR | 121, 129 | |

| U18666A | IAV | Annexin A6 | 499 | |

| UV-4B | DENV, IAV | ER glycosylation pathway | 500 | |

| Tyrphostin A9 (A9) | IAV, SINV, HSV-1, MHV, RV | PDGFR | 121, 129 | |

| Verapamil, chlorpromazine | IAV, SINV, VSV | Calcium channel blocker | 501, 502 | |

| Gemfibrozil, lovastatin | IAV | Unknown | 503 | |

| Suramin | ZIKV | Glycosylation (secretory pathway) | 504, 505 | |

| Dynasore | HSV | Protein trafficking | 422 | |

| DEBIO-025 | HCV | Cyclophilin A | 506, 507 | |

| Bortezomib | ZIKV | Proteasome function | 417 | |

Abbreviations: AAK1, adaptor-associated protein kinase 1; AdV, adenovirus; AstV, astrovirus; BDV, Borna disease virus; BPXV, buffalopox virus; BHV1, bovine herpesvirus 1; BEFV, bovine ephemeral fever virus; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; CVB3, coxsackievirus B3; cIAP2, cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 2; CLK1, Cdc2-like kinase 1; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CoV, coronavirus; DGAT1, diacylglycerol acyltransferase-1; DENV, dengue virus; DHODH, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase; EAV, equine arteritis virus; EBOV, Ebola virus; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EMCV, encephalomyocarditis virus; EV, enterovirus; eIF4E, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E; ERK, extracellular-regulated kinase; FLV, flavivirus; FAS, fatty acid synthase; FMDV, foot-and-mouth disease virus; GAK, cyclin G-associated kinase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; HMG-CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A; hnRNPA1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1; hRSV, human Rous sarcoma virus; hCMV, human cytomegalovirus; hAdV, human adenovirus; hRhV, human rhinovirus; HSV-1, herpes simplex virus 1; IAV, influenza A virus; IBV, influenza B virus; IMPDH, IMP dehydrogenase; JEV, Japanese encephalitis virus; JUNV, Junin virus; MHV, mouse hepatitis virus; MNK1, MAPK-interacting kinase 1; NDV, Newcastle disease virus; NGFR, nerve growth factor receptor; NPC1L1, Niemann-Pick C1-like 1; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; OSBP, oxysterol-binding protein; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PIV, parainfluenza virus; PEDV, porcine epidemic diarrhea virus; PI4KB, phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIβ; PKC, protein kinase C; PPRV, peste des petits ruminants virus; PRRSV, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus; PyV, polyoma virus; RACK1, receptor for activated C kinase 1; RVFV, Rift Valley fever virus; RSV, Rous sarcoma virus; RV, rotavirus; SERCA, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; SV, Sendai virus; SINV, Sindbis virus; SirT1, Sirtuin type 1; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus; VEEV, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus; WNV, West Nile virus; XPO1, exportin 1; ZIKV, Zika virus.

Kinase inhibitors.

Completion of the Human Genome Project in 2002 identified 518 kinases that are collectively known as the cellular “kinome” (97). Kinases are implicated in various physiological processes to maintain cellular homeostasis, and their dysregulation could result in pathology. Infections by pathogens, including viral infections, are also associated with perturbation of the “kinome” (98, 99). Each step of the virus replication cycle can be regulated by multiple kinases (100–102). Some of the cellular kinases are dispensable for host cell viability but might be needed during virus infection (102). Such kinases represent potentially valuable drug targets (Fig. 1A). Kinase function can be inhibited by small molecule chemical inhibitors (103), and this approach is used in the cancer field. The topic has been extensively reviewed (104–120). Out of the hundreds of different kinase inhibitors developed so far, only 38 have been licensed for use as anticancer agents. Kinase inhibitor libraries have also been screened for antiviral activity, and some promising candidates have emerged as potential inhibitors of different steps of the viral life cycle (37, 38, 121–128).

The viral replication cycle is a multistep process that includes attachment, entry, genome synthesis, assembly of newly synthesized virion particles, and budding. Each step of the viral life cycle involves host cell kinases (Table 2), with a single kinase regulating one or multiple steps of the viral life cycle. For example, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-interacting kinase 1 (MNK1) inhibitor CGP57380 inhibits only initiation of buffalopox virus (BPXV) protein synthesis (38). In contrast, against IAV, the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitors AG879 and A9 can block multiple steps, including viral RNA synthesis, export of viral ribonucleoproteins (vRNP), and budding (121). While the precise mechanism by which RTK regulates viral RNA synthesis is not known, regulation of vRNP export and budding is mediated via the CRM1 (chromosomal maintenance 1) nuclear export pathway and the farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (lipid biosynthesis enzyme), respectively (121). It is likely that targeting signaling pathways that regulate multiple steps of the viral life cycle will represent more effective antiviral approaches (121).

All members of a particular virus family usually share the same kinase requirements. For example, SERCA (sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase) inhibitor blocks replication of multiple Paramyxoviridae family members (39). Nevertheless, some kinases are essential for multiple virus families and hence can represent potential targets for developing broad-spectrum antiviral drugs (121, 129). One such example is the RTK inhibitor AG879, which is active against IAV, rhesus rotavirus, Sendai virus, coronavirus, herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), and Pichinde virus (an arenavirus) (121, 129).

Lipid biosynthesis inhibitors.

Besides nucleotides and amino acids, many viruses need a continuous supply of cellular fatty acids during their replicative cycle (130, 131). To achieve this, viruses may need to reprogram cellular metabolism, including lipid synthesis, to facilitate their own optimal replication (131, 132). Treatment of cells with chemical inhibitors that suppress fatty acid biosynthesis results in decreased virus production (121, 133–136), an approach that has shown promise against dengue virus (DENV), Zika virus (ZIKV), and West Nile virus (WNV) (137).

Acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) carboxylase (ACC), ATP citrate lyase (ACLY), and fatty acid synthase (FASN) are known to regulate fatty acid biosynthesis in eukaryotic cells (138). Targeting ACC with the chemical inhibitor 5-(tetradecyloxy)-2-furoic acid (TOFA) and 3,3,14,14-tetramethylhexadecanedioic acid (MEDICA 16) has been shown to reduce flavivirus (WNV and Usutu virus [USUV]) replication (134). These compounds act by reducing cellular levels of multiple lipids, such as glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, and cholesterol (134). Additionally, the lipid biosynthesis inhibitor TOFA and cerulenin exhibit broad-spectrum antiviral activity against ZIKV (Flaviviridae) and Semliki Forest virus (Togaviridae) by blocking ACC and FASN, respectively (133). Improved technologies, such as lipidomics, should provide insights into reprogramming of lipid metabolism following viral infections. However, caution is warranted, since targeting host lipid metabolism as an antiviral strategy may be limited by toxicity to host cells (139).

Besides targeting cellular kinases and fatty acid synthases, small molecule chemical inhibitors have also been developed against other protein/lipid targets, and these are summarized in Table 2. Other types of inhibitors include the relatively new class of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that can be used to target certain host factors required for virus infection and replication. These are described in the following section.

Host-directed therapeutic monoclonal antibodies.

Rather than examining the role of antibodies directed against viral proteins, our focus in this section is to highlight the role of antibodies directed against host components when the net outcome is antiviral. For example, antibodies such as UB-421 (140), ibalizumab-uiyk (141), and maraviroc (80, 81), which block receptor binding sites on CD4+ T cells, have shown clinical efficacy in treating HIV-1 infection (21).

Cellular tight-junction proteins, such as claudin (142) and occludin (143), may act as entry receptors for viruses such as HCV (142–145). Thus, anti-claudin1 (CLDN1) (146) and anti-occludin (147) monoclonal antibodies have been designed and shown to inhibit HCV infection with minimal side effects. Similarly, the human scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR-BI), is a presumed receptor for HCV, and targeting this molecule may represent a useful therapeutic approach (148). However, HCV variants with decreased SR-BI dependency, which could limit the use of SR-BI targeting therapy, have been described previously (149–151). Interestingly, humanized mice infected with HCV variants that had increased in vitro resistance to SR-BI-targeting molecules still remain responsive to anti-SR-BI MAb therapy in vivo (152), hence representing an effective way to combat HCV infection (152).

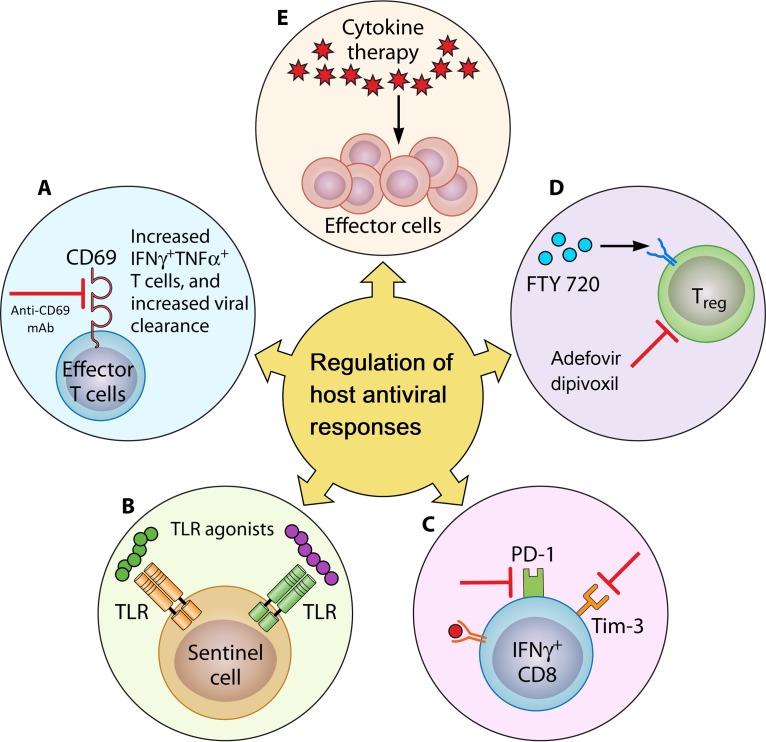

Antibodies directed toward other cellular proteins (other than viral receptors) have also been developed. For example, blocking CD69 (a transmembrane C-type lectin protein in the host that is highly expressed by leukocytes upon infection) using anti-CD69 monoclonal antibodies can increase leukocytic numbers in secondary lymphoid organs during infection. This promotes clearing of vaccinia virus infection (153) (Fig. 2A). Anti-CD69 also increases the numbers of gamma interferon (IFN-γ)- and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-producing natural killer (NK) and adaptive immune T cells, an effect mediated in part by mTOR signaling (154, 155). Other studies have documented the therapeutic potential of bevacizumab (a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody directed against vascular endothelial growth factor) to inhibit HSV-1-induced corneal neovascularization and also scarring in herpetic stromal keratitis (156, 157).

FIG 2.

Regulation of host antiviral responses. An antiviral immune response can be boosted by several possible means. (A) Monoclonal antibodies. Blocking CD69 by using anti-CD69 monoclonal antibodies increases leukocytic numbers in the secondary lymphoid organs during infection and improves the capacity to clear viral infection. (B) PRR agonists. Agonists targeting PRRs are another possible strategy to potentiate the innate immune response for enhanced virus clearance. (C) Modulation of counterinflammatory mechanisms. Counterinflammatory mechanisms such as the Tim-3/Galectin-9 interaction and the PD-1/PDL-1 axis prevent collateral tissue damage caused by an excessive immune response. Thus, antiviral immunity can be augmented by blocking these counterinflammatory mechanisms. (D) Manipulating Treg responses. Treg are the suppressor cells that act to limit an excessive immune response. FTY720 expands and potentiates Treg function, which in turn ameliorates virus-induced immunopathology. On the other hand, inhibiting Treg (adefovir dipivoxil) enhances antiviral effector responses. (E) Cytokine therapy. Administration of proinflammatory cytokines and alternatively a blockade of immunosuppressive cytokines may serve to enhance antiviral immune responses.

Monoclonal antibodies have been used as adjunct therapeutic agents along with antiviral therapy. For instance, oral anti-CD3 antibody therapy can cause significant reductions in viral load and an increase in regulatory T-cell levels in chronic HCV patients who additionally receive IFNs plus ribavirin therapy (158).

It is noteworthy that host-directed antiviral therapies (e.g., monoclonal antibodies and other types of inhibitors) offer several advantages over virus-directed interventions. Compared to virus-directed agents that exert genotype-dependent antiviral activity, host-directed agents show broad-spectrum pan-genotypic activity. For example, monoclonal antibodies directed against SR-BI (159, 160), CLDN1 (161), and CD81 (162, 163) have shown broad-spectrum antiviral efficacy against multiple HCV genotypes. Likewise, host-directed agents such as ITX-5061 (164), erlotinib (165), ezetimibe (166), flavonoids (167, 168), lectins (169), and phosphorothioate oligonucleotides (170), as well as silymarin (171, 172), exhibit antiviral activities against multiple genotypes of HCV. Host-directed agents also restrict replication of viral escape variants. For example, besides blocking entry of all major HCV genotypes, monoclonal antibodies directed against CLDN1 can also inhibit cell entry of highly infectious neutralizing antibody escape variants of HCV (161). As a result, recent developments of clinically useful monoclonal antibodies and other host-directed agents have revolutionized strategies for antiviral therapy.

Regulating Host Antiviral Responses

An alternative to using drugs that directly target either viral events or physiological processes involved in replication in infected cells is to target the various host immune events set into play by viral infections. In response to infection, viruses can trigger a wide range of host responses that usually act to eventually control the extent of the infection and remove virus from the host (Fig. 2). Such events can be changed by an expanding series of therapies to facilitate host-directed viral control and to limit the extent of tissue damage caused by the infection. These strategies are discussed in the following sections.

Induction of the IFN pathways.

Viruses themselves may possess one or more pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which can be proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids. These PAMPs interact with cellular pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to induce innate immune events such as IFN production (173–178). Cells respond to IFNs by changing the expression of a multitude of cellular proteins, collectively known as IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) (179, 180). These function to protect the responding cells from viral replication and therefore help to resolve infections (181, 182). Other molecules produced in response to viral infection may participate in the cellular inflammatory response, and these too can exert antiviral control, although if overstimulated may contribute to tissue damage, as is typical during many chronic viral infections (183, 184).

The best-studied examples of viral PAMPs are those which trigger the cellular Toll-like receptors (TLR). Such interactions result in a cascade of events that include cell activation, the production of cytokines, and several other activities that can modulate the outcome of viral infection (185, 186) (Table 3). The PRRs may be triggered by synthetic ligands. For instance, administration of the TLR7 agonist GS-9620 may expand NK cells and HBV-specific T cells, which leads to better control of chronic HBV infection (187) (Fig. 2B). Likewise, the TLR7/8 agonist R848 can block ZIKV genome and protein synthesis in human monocytes via the activation of viperin, an antiviral protein (188). Similarly, TLR9 and TLR3 agonists can inhibit HCV and HBV replication, respectively (189).

TABLE 3.

Regulation of host antiviral responsesa

| Antiviral agent(s) and functional category | Virus(es) | Host target | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist of the innate immune receptors | |||

| Rintatolimod (Ampligen) | HIV, HCV, HBV | TLR3 agonist | 189 |

| GS9620, RO6864018, RO7020531, AL-034, imiquimod (Aldara) | HBV, HPV | TLR7 agonist | 21, 508 |

| GS9688 | HBV | TLR8 agonist | 508 |

| CL097 | HIV | TLR7/8 agonist | 189 |

| PF-04878691 or 852A | HCV | TLR7/8 agonist | 189 |

| CPG10101, IMO-2125, SD-101 | HCV | TLR9 agonist | 189 |

| Inarigivir (SB 9200) | HBV | RIG-I agonist | 508 |

| Regulation of inflammatory pathway | |||

| IFN-α, PegIFN-α, Alferon N | HPV, HCV, HBV | TNF-α-mediated antiviral activity | 21 |

| Quercetin | JEV, HCV | TNF-α-mediated antiviral activity | 509–511 |

| A23187 | SINV, VSV | Ca2+ efflux-mediated antiviral immunity | 512 |

| Phorbol myristate acetate | HBV | Synthesis of NF-κB-mediated antiviral protein | 513, 514 |

| CI1033 | Variola virus | ErbB1(EGFR)-mediated antiviral immunity | 515 |

| SIP agonist | IAV | Suppression of virus-induced cytokine storm | 516, 517 |

| COX-2 depletion | IAV | Induction of type I IFN-mediated antiviral immunity | 518 |

| Statins | IAV | Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects | 519, 520 |

| PPAR agonist | IAV | Suppression of virus-induced cytokine storm and associated lethality in mice | 521–524 |

Abbreviations: COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; DHV, duck hepatitis virus; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; IAV, influenza A virus; JEV, Japanese hepatitis virus; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ; SINV, Sindbis virus; SIP, sphingosine-1-phosphate; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus.

Unlike cellular RNA, some viral RNAs contain a 5′ triphosphate (5′ppp) terminal structure. This is sensed by the cellular retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), a member of the cytosolic PRR family that also activates intracellular signaling cascades to induce proinflammatory cytokine responses (190, 191). Administration of synthetic 5′ppp RNA may also activate RIG-I-dependent antiviral responses to provide significant protection against a diverse group of RNA and DNA viruses (192).

Certain drugs and biologicals that stimulate IFNs have been developed, and these have contributed to controlling virus infection. For instance, virus replication is suppressed by hydroxyquinolines, a class of small molecule compounds that activates IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) of the type I IFN pathway (193).

Augmentation of host antiviral responses by inhibiting counterinflammatory pathways.

Host counterinflammatory pathways function to inhibit the collateral tissue damage that might occur as a consequence of excessive immune responses generated against a viral infection. On the other hand, host counterinflammatory mechanisms also dampen effective immunity to acute viral infections. For example, in a mouse model of IAV infection, a TIM-3/Galectin-9 immunoinhibitory interaction can act to limit collateral damage by inducing apoptosis of TIM-3-positive CD8+ T cells that mediate the damage (194). However, unfortunately, the approach can impair antiviral control, which is also mediated by CD8+ T cells. Accordingly, blocking the TIM-3/Galectin-9 immunoinhibitory interaction using TIM-3 fusion protein can enhance antiviral immunity by generating a more robust acute-phase virus-specific CD8+ T-cell response as well as increased levels of virus-specific serum IgM, IgG, and IgA antibodies (194) (Fig. 2C).

Other immune-directed approaches include blockade of the coinhibitory receptor programmed death-1 (PD-1). This has been used to control chronic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in macaques with antibody to PD-1. This enhances protection via effects on virus-specific CD8+ T-cell function (195) (Fig. 2C). Others have also reported the benefits of controlling virus infection using MAbs that target inhibitory receptors, and the approach seems to have a promising future (196).

Another potential immune-directed strategy to combat virus infections is to target the function of regulatory T cells (Treg), which often act to diminish excessive inflammatory responses. Although Treg have beneficial effects against inflammatory reactions to viruses, the downside is potentially limiting protection, especially to acute infections (197). Thus, Treg activity needs to be therapeutically managed to potentiate antiviral immunity (Fig. 2D). For example, an acyclic nucleotide analogue of adenosine used against chronic HBV infection (198) inhibits Treg function as well as its expansion (199) but is mildly nephrotoxic. Similarly, TNF-α inhibited the suppressive effect of Treg, and this resulted in enhanced HBV-specific immune responses (200). However, inhibition of virus‐specific Treg can be a technically challenging issue for various reasons, as described in a recent review article (201). Besides directly regulating antiviral responses, manipulation of Treg can also ameliorate the tissue damage caused by viral infections. For example, long-term application of the sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor agonist FTY720 results in anti-inflammatory effects (202) in HSV-1-induced immunopathology. These effects of FTY720 were mediated by the conversion of T-cell receptor (TCR)-stimulated nonregulatory CD4+ T cells to Treg with increased suppressive activity. A plethora of inhibitory pathways of the immune system are important for maintaining self-tolerance and minimizing collateral tissue damage. It is also well understood that viruses coopt certain immune checkpoint pathways as a major mechanism of immune resistance, particularly against T cells that are viral antigen specific. Immune checkpoint modulation is thus a viable emerging treatment modality. However, careful consideration should be exercised before any treatment decisions are made.

Cytokine therapy.

Attempts have been made to enhance the therapeutic effect of antiviral adaptive immunity by administering cytokines. There are three phases of the T-cell immune response: expansion, contraction, and memory (203, 204). Interleukin 2 (IL-2) therapy during the contraction phase of an antiviral immune response can result in enhanced proliferation and survival of virus-specific T cells as well as a drastic reduction in viral titers (205) (Fig. 2E). However, IL-2 treatment during the expansion phase had a negative impact on the survival of rapidly dividing effector T cells (205). Similarly, in chronic HBV patients, the virus can be controlled using therapies that stimulate certain cytokines. For example, Peg-IFN-λ treatment achieves control likely by inducing high serum levels of IL-18 (antiviral cytokine) along with sustaining both IFN-producing HBV-specific CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T-cell responses (206). These enhanced immune activities can severely restrict virus replication (13). On the other hand, immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10, can suppress antiviral immunity, and overcoming this effect can result in enhanced viral control, as has been observed with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection (207).

Regulation of cytokine storm.

The term “cytokine storm” is used to describe aberrant production of cytokines and the tissue-damaging immunopathology they orchestrate. Originally, “cytokine storm” was coined to characterize pathology associated with organ transplantation, as demonstrated by an inflammatory response triggered by the donor immune cells reacting to the recipient patient host’s tissues (graft-versus-host disease) (208). Cytokine storm has also been correlated with increased disease severity, particularly in cases of acute viral infections (208). These include IAV (209, 210), DENV (211, 212), and Ebola virus (EBOV) (213) infections. Over 150 cytokines may be involved in a cytokine storm (211–213), but those primarily involved include TNF-α, IL-6, and IFNs.

Controlling cytokine storms by targeting host proteins involved in the activation of cellular signaling pathways is a potential approach to dampen tissue damage (214). For example, the highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus induces a robust cytokine response in comparison to seasonal flu (H1N1) (215). In addition, the highly pathogenic “Spanish flu” (H1N1 IAV strain), which caused a catastrophic pandemic in 1918-1919, was also shown to induce hypercytokinemia in ferrets (216). Since hypercytokinemia involves multiple cytokines, disrupting a single cytokine usually has limited value (215, 217). However, since the induction of the majority of the cytokines is mediated via activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, targeting this transcription factor may be a therapeutically viable approach. For example, in a knockout mouse model of H5N1 infection, depletion of NF-κB (p50 subunit) resulted in a drastic reduction in the expression of the NF-κB-regulated cytokines and chemokines (lack of hypercytokinemia) (215, 218).

In one highly pathogenic IAV infection (H5N1), the majority of patients who experienced a cytokine storm were elderly or had compromised immune systems (219). In fact, a relevant question is why certain individuals are relatively resistant to cytokine storms whereas others are more susceptible. Hyper- and hyporesponders to bacterial products have also been identified in patients, which can be explained in part by differences in structure and function of their TLR1 proteins (220). Thus, the association between high host susceptibility to virus-induced cytokine storms and genetic polymorphisms in the PRRs needs to be explored in more detail.

Modulating Epigenetic Modifications

Epigenetics is the study of phenotypic changes which do not involve nucleotide variations in the genome of the organism (221). Major epigenetic changes that take place in cells are due to histone modifications (acetylation and methylation), phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation. Histones interact with genomic DNA to form chromatin structures. The level of chromatin compaction depends primarily on methylation and/or acetylation of the histone proteins (222), and this determines genomic stability, gene expression, cell lineage development, stem cell maturation, and mitosis (223). Histone modifications are carried out by epigenetic regulators, such as histone acetyltransferases (HATs), histone deacetylases (HDACs), and histone methyltransferases (HMTs), and these factors have been targeted to treat cancers (224) and parasitic diseases (225). Likewise, DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), which regulate DNA methylation, have been associated with many different diseases (226, 227). Recent reports also highlight the involvement of these epigenetic modifiers in regulating virus replication (228–231). For instance, epigenetic modifications can serve as an antiviral defense mechanism by suppressing transcription and replication of the viral genome. On the other hand, viruses may also epigenetically modulate host functions by inducing DNA hypermethylation of the host genome upon virus infection (232). Therefore, ongoing efforts to develop inhibitors of epigenetic regulators (Fig. 1B) to control gene expression during viral infection are warranted.

Histone acetylation and deacetylation.

Histone acetylation and deacetylation are the processes by which the lysine residues within the N-terminal tail that protrude from the histone core of the nucleosome are acetylated and deacetylated during gene regulation (233). Histone acetylation is regulated by HATs and HDACs, and chemical inhibitors of HDACs have been evaluated for antiviral effects. For example, the selective HDAC6 inhibitor tubacin has been shown to block Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) (234) and HCV (235) replication. The mechanism involved induction of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90; an HDAC6 substrate) hyperacetylation that inhibits Hsp90 and JEV NS5 interaction to block viral RNA synthesis (234). Similarly, the HDAC inhibitor SAHA (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid) can inhibit HCV replication by increasing H3 acetylation levels (236) of an immunomodulatory protein, osteopontin (237).

In an in vitro model of latent HSV-1 infection, treatment with trichostatin A (TSA) and sodium butyrate (HDAC inhibitors) of quiescently infected PC12 cells (rat neuroblastoma) was shown to reactivate virus replication (238), suggesting that epigenetic modifications may be exploited to understand the issue of viral latency. Like other herpesviruses, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) persists mainly as an episome (also called a covalently closed circular DNA [cccDNA]) in latently infected B lymphocytes (239). During latency, viral DNA is maintained with relatively low levels of histone acetylation. Expression of the viral BZLF1 protein is associated with viral lytic reactivation (240). Its expression is blocked by the recruitment of cellular repressive factors such as YY1 (Yin Yang 1) and ZEB (zinc finger E-box-binding factor). These prevent access of transcriptional activators and facilitate binding of repressive cofactors such as HDAC (240). Therefore, HDAC inhibitors can induce reversal of EBV latency.

Although these HDAC inhibitors have the potential for use as promising therapeutic agents, a careful assessment prior to their use is essential, as they have the potential to reactivate other latently infected viruses in the host’s genome (241). For instance, administration of SAHA/TSA can increase the severity of coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3)-associated myocarditis (242).

Controlling chronic HBV infection, which represents a major problem, might be achieved by manipulating epigenetic events in chronically infected cells. HBV genomes in viral particles remain in a circular, partially double-stranded DNA conformation that is transcriptionally inert (243). To become transcriptionally active, it is converted into cccDNA (episome) in the nuclei of infected cells (244, 245). Once infection has occurred, the virus persists indefinitely in the nuclei of hepatocytes as cccDNA. Currently approved antiviral therapy, based on nucleoside analogs, targets cytoplasmic HBV genomic replication without directly affecting cccDNA and therefore necessitates long-term antiviral therapy (246–250). Total cure of chronic HBV can be achieved only if the viral episomes are removed from the nuclei of all hepatocytes. The formation of cccDNA by HBV is facilitated by the cellular transcriptional machinery (251), which also involves epigenetic modifications (251, 252). The epigenetic inhibitor C646 (HAT inhibitor) transcriptionally silences cccDNA without any measurable toxicity, thus representing a novel approach to the therapy of chronic HBV infection (253).

Histone methylation.

HMTs are of two types, histone-lysine N-methyltransferases and histone-arginine N-methyltransferases. HMT inhibitors have proven their therapeutic potential against certain types of cancer, and they might be effective in regulating some viral infections. For example, PRMT5 (protein arginine methyltransferase 5) restricts HBV replication, which is mediated via epigenetic repression (demethylation of arginine residues at the arginine-rich C-terminal domain) of viral DNA transcription (254). Thus, PRMT5 agonists are valuable for repressing HBV DNA transcription (255).

Another potential use of HMTs is to manipulate HSV latency. The transcriptional repressor CTCF, also known as CCCTC DNA binding factor or 11-zinc finger protein, is a transcriptional factor in the human genome encoded by the CTCF gene. This can bind to HSV-1 DNA and promote HSV-1 lytic transcription. CTCF depletion by siRNA can cause an increase in repressive histone marks H3K27me3 and H3K9me3, concomitant with decreased transcription of HSV-1 genes (256). Likewise, treatment with 5′-deoxy-5′-methylthioadenosine (MTA; a protein methylation inhibitor) can suppress the level of H3K4me3 (mediated via methyltransferase Set1), which eventually results in reduced HSV-1 transcription and replication (257).

Histone demethylation.

DNA viruses encapsidate their genomes without histones but rapidly acquire chromatin structure following infection (258, 259). Therefore, they are subjected to modification by the host epigenetic modifiers, which can be inhibited to regulate viral replication. For example, inhibition of lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1; KDM1A family) results in inhibition of transcription and lytic replication of the DNA viral genome. This results in reduced virus shedding and decreased disease severity (260–264). Unlike DNA viruses, RNA virus genomes do not depend on histone association and chromatin structure. However, surprisingly, LSD1 indirectly inhibits IAV replication by demethylating and activating interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3), which serves as a cellular antiviral protein for IAV and several other RNA viruses (265). Additionally, even though HIV-1 is an RNA virus, blocking LSD1 activity has also been shown to suppress the proviral DNA activation of HIV-1 transcription in latently infected T cells. This effect is mediated by demethylation of the viral accessory Tat protein (266).

DNA methylation.

DNA methylation is a well characterized epigenetic modification that is associated with many different diseases, including microbial infections and cancers (226, 227). DNA methylation is most dynamic in CpG islands near transcription start sites (222). CpG islands are typically hypomethylated in comparison to the rest of the genome. Generally, promoter methylation represses gene transcription, while methylation at other regions of the genome induces gene transactivation (222). The chromatin structure undergoes changes following DNA methylation (267, 268) and during interaction with HDAC/DNMTs (269, 270). DNMTs bind the methyl group (-CH3) at the carbon 5 position of cytosine in CpG dinucleotides to methylate DNA (271). Hypermethylated DNA, which negatively correlates with hypoacetylated histones, leads to chromatin condensation and hence transcriptional repression (267).

By suppressing transcription and replication of the viral genome, DNA methylation serves as an antiviral defense mechanism. Endogenous retroviruses and retrotransposons are well known to be repressed by DNA hypermethylation (272). The genome of DNA viruses such as HPV, HSV-1, HBV, EBV, and adenovirus also undergo abundant methylation and are often silenced in the infected cells (273–277). The silenced viral genomes can be reexpressed by manipulating epigenetic events. For example, treatment with 5-azacytidine (decitabine), a DNMT inhibitor, induced activation of silenced EBV genomes. This eventually facilitated immune-mediated destruction of EBV-associated tumor cells (278, 279). However, demethylating agents can also activate retroviral RNA transcription from its dormant (latent) stage (280), a potential problem for therapy.

Viruses may also epigenetically subvert host functions by inducing DNA hypermethylation (281, 282). For example, HCV infection induces DNMT1 and 3b-mediated DNA hypermethylation. This leads to downregulation of expression of E-cadherin, a primary cell adhesion molecule with tumor suppressor activity (283). The effect can be reversed following treatment with a DNMT-specific inhibitor (283). Similarly, methylation of SOCS1 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 1, a negative regulator of JAK/STAT signaling) negatively correlated with HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma (284). Likewise, the promoter of GADD45 (growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene 45), a tumor suppressor gene, has been shown to be hypermethylated during HCV infection in mice (285). By regulating multiple DNMTs, DNA tumor viruses such as HPV and HBV induce aberrant DNA methylation (286–288), which can eventually result in carcinogenesis (289).

Techniques such as photo-cross-linking-assisted m6A sequencing (PA-m6A-seq), high-resolution mapping of N6-methyladenosine using m6A cross-linking immunoprecipitation (m6A-CLIP), bisulfite sequencing, 5-methylcytosine RNA immunoprecipitation (m5C-RIP), 5-azacytidine-mediated RNA immunoprecipitation (Aza-IP), and methylation-individual nucleotide resolution cross-linking immmunoprecipitation (miCLIP) have all emerged as powerful tools to profile epigenetic modifications in viral and host genomes (290–294). These techniques, when combined with chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), can provide comprehensive information on the multiprotein complexes associated with epigenetic control of viral infections. In addition, elucidating the role of other modes of posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation or sumoylation, can provide insights into dynamic virus-host interactions (294).

MODERN APPROACHES OF ANTIVIRAL THERAPY AND TO IDENTIFY HOST FACTORS FOR ANTIVIRAL DRUG DEVELOPMENT

Drug Combination Approach

The appropriate use of drug combinations may result in enhanced potency and broadened antiviral activity and may lessen the chance of drug resistance (295, 296). As discussed above, the addition of ribavirin to PegIFN-α-based regimens provided dramatic improvement of chronic HCV control (53, 297). However, the mechanism by which IFN-α and ribavirin act against HCV has not been elucidated. Other combinations have also proven effective against HCV. For example, Xiao and colleagues showed that a combination of host-directed agents (erlotinib, dasatinib), host-directed antibodies (anti-CLDN1, anti-CD81, and anti-SR-BI), and virus-directed agents (telaprevir, boceprevir, and simeprevir or danoprevir, daclatasvir, mericitabine, and sofosbuvir) were highly effective against HCV (298).

A new avenue in the use of drug combinations may be to simultaneously target multiple host factors and pathways that are supportive of virus replication (299, 300). It is an added advantage if the host-directed agents have already been FDA approved. Such drugs can be used immediately to treat viral infections, an approach known as drug repurposing (299, 301–303). Because the targets of these drugs have already been well characterized and validated, they present with little to no safety issues and risks. To determine which drugs might be appropriately combined to exploit their different mechanisms of action, a number of new approaches have been tried and are discussed below.

Antiviral Drug Development in the Era of Precision Medicine

There is a significant gap in our understanding about how different individuals develop disease and respond to treatments. Traditional medicine is based on the “one-size-fits-all” approach, and this may miss its mark, because each person’s genetic makeup is slightly different from that of others. The promising idea of precision medicine (also known as personalized medicine, individualized medicine, or genomic medicine) is to cater healthcare to each person’s unique genetic makeup. However, this new technology is still being validated and may take several years to become clinically feasible. Regardless, it is important to consider the individual’s uniqueness when developing antiviral drugs, as this uniqueness can have an important impact on the outcome of therapies.

Patient-to-patient variability in the outcome of antiviral therapies might be due to different genetic profiles as well as the variable microbiome present in the individual (304, 305). The latter could influence host pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles as well as drug distribution (306). The advent of methodologies to comprehensively characterize patients at genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and lipidomic levels along with the availability of computational tools to analyze global protein-protein interactions (interactome) has greatly improved biological databases (307). Employing these “omics” approaches to classify clinical populations into mechanistic subgroups is likely to result in a higher success rate of treatment modalities, including antiviral therapies (306).

One potential application of precision medicine is to predict the outcome of viral infections in different individuals. For example, IAV infection may induce robust proinflammatory cytokine responses, with some individuals experiencing severe disease. Under such circumstances, steroids are usually not advisable because they may promote virus replication (308). Furthermore, anti-inflammatory therapy aimed to dampen inflammatory responses has been successful but only in a few patients (308). Under such circumstances, the availability of “omics” data (biomarkers) should prove valuable to explain individual variations, to monitor immune responses, and to assess disease severity in individual patients.

Another application might apply to HIV-1 control. In HIV-1, restoration of CD4+ T-cell numbers is critical after initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) (309). However, it is evident that not all HIV-1 patients experience a rebound in their CD4+ T-cell counts, and they are therefore vulnerable to opportunistic infections (309, 310). Determining the genetic factors which predict different levels of patients’ responses to ART is key to optimal treatment outcomes. For example, the pattern of gene expressions by peripheral blood monocytes (PBMCs) of an individual patient can predict if certain individuals recover their CD4+ T-cell counts (311). Similarly, a polymorphism in the MDR-1 gene in patients has been associated with more potent responses to ART than of patients lacking certain polymorphisms (312–315). Polymorphisms in genes encoding drug transporters and metabolic enzymes are also important factors in determining concentrations of antiretrovirals in plasma (316–320). It is noteworthy that besides host genetic factors, alterations in the microbiome of individual patients may also influence the outcome of viral infections or vaccination (304). This is an important topic that has been discussed elsewhere (304, 321).

Genome-Wide Screens To Identify Host Factors for Drug Development

Classical reductionist approaches by studying the role of a single or a limited number of proteins do not provide a holistic view of all the cellular factors that can support virus replication. Modern drug development has been fueled by the advent of high-throughput genome-wide technologies, such as RNAi and CRISPR screens, which permit the simultaneous evaluation of multiple molecular targets. Data generated from the new high-throughput approaches have proven to be invaluable in assembling novel hypotheses and in identifying new and useful diagnostic biomarkers.

siRNA screens.

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are artificially synthesized, 19- to 23-nucleotide-long double-stranded RNA molecules designed to specifically target a cellular mRNA for degradation (322). Through genome-wide RNAi screening assays, thousands of distinct host factors have been shown to either facilitate or inhibit replication of a variety of viruses (323–350). It is, however, less well understood how the majority of these cellular factors may impact the life cycle of different viruses. For instance, a total of 1,362 virus-supportive host factors have been identified in seven different IAV RNAi screens performed to date. The overlapping genes were shown to regulate various steps of the virus replication cycle (351–355). However, only a few of the thousands of identified host factors, such as NF-κB (96), members of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway (36), and RTKs (121, 129), are known to facilitate IAV replication. Among the thousands of virus-supportive host factors identified, only a relatively small fraction show overlap in multiple independent screens (e.g., 113, 14, and 6 factors were found to be common in two, three, and four individual screens, respectively). It is noteworthy that no common host factors have been identified among all seven IAV RNAi screens performed to date. We therefore can conclude that RNAi screens can provide a holistic view on host dependency factors for virus replication. However, data reproducibility among different screens (due to various inherent or other uncontrollable variability issues) and determination of definitive mechanistic insights for the involvement of many of the different host factors in virus replication can be challenging (356). This problem can perhaps be overcome by the use of a lentivirus-based pooled RNAi screen. In this method, cells are first infected with a pool of lentiviruses at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) (0.1 to 0.3) to express the diverse pool of siRNAs. Subsequently, cells are challenged with the target virus of interest in order to produce cytopathic effects. The surviving cells are then propagated and used for next-generation sequencing (NGS). This identifies siRNA targets (host genes) responsible for providing protection against virus-induced cell death (329, 330).

CRISPR/Cas9 screens.

As discussed above, the RNAi approach to identify exploitable host targets for antiviral drug development can be challenging, but the recently developed CRISPR/Cas9 approach portends to be an improved method. While RNAi produces a weak phenotype (partly because it is not possible to achieve 100% transfection efficiency), the cellular CRISPR/Cas9 machinery completely disrupts its targeted protein and thereby can produce a more robust phenotype (357). The genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 knockout (GeCKO) technique can successfully identify cellular factors required for virus replication (358–367). This approach has many advantages over RNAi screens. For example, while the number of proviral host factors identified by seven IAV RNAi screens ranged from 90 to 323, the GeCKO screen identified a maximum of 453 proinfluenza host genes (359). Furthermore, the GeCKO screen identified at least 33 common proinfluenza host genes, compared to 2 to 16 identified by various RNAi screens (359). The GeCKO screen also revealed >400 rare host genes required for IAV replication that were not found in previous RNAi screens (359). Likewise, three independent GeCKO screens with flaviviruses (FLVs) identified the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated protein complex as key cellular factors for efficient FLV replication. This indicated a higher reproducibility than that of RNAi screens (360, 362, 363). HIV-1 coreceptors, namely, solute carrier family 35 member B2 (SLC35B2), activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM), and tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase 2 (TPST2) (336–341), as well as norovirus (NV) cellular receptor CD300If (367), were also identified by GeCKO screens.

In loss-of-function-based GeCKO/RNAi screens, identification of host restriction or dependency factors is based on the increase or decrease in viral titers. However, certain cellular factors do not directly contribute in regulating virus production but instead regulate cell death pathways. For example, Ma and colleagues have identified EMC2, EMC3, SELL1, DERL2, UBE2G2, UBE2J1, and HRD1 as highly enriched genes, all of which belong to ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) pathways in a GeCKO screen for WNV. These genes exhibit no impact on virus production but have been associated with WNV-induced cell death (364).

Several factors must be considered when conducting and interpreting data produced by RNAi and GeCKO screens. Considering the level of genetic redundancy in animals, the variable levels of the efficiency of RNAi and GeCKO screens, and the diversity of experimental conditions, off-target effects that contribute to the relatively high rate of false-positive results can sometimes occur. This coupled with the relatively low rate of verification of the selected genes highlights the need for validation to confirm that the identified host genes are indeed coopted for virus replication.

CHALLENGES IN DEVELOPING HOST-DIRECTED THERAPIES

Drug Resistance against Host-Directed Antiviral Agents

As discussed before, since viruses cannot easily replace the missing cellular functions by mutagenesis, it is thought that viruses are unlikely to develop drug resistance against agents that target host factors needed for virus replication (37). However, emerging evidences suggest that viral resistance against host-directed antiviral agents can indeed occur (Table 4). In a cell culture model, clinically relevant IAV-directed agents may induce a completely resistant phenotype in a short period of time, such as after six passages (P6) (129). However, at this passage level, no drug-resistant IAV variants are known to be selected in the presence of host-directed agents in cell culture (129). Other attempts have also failed to derive drug-resistant virus variants against host-directed agents at up to ∼P25 (129, 368, 369). However, upon further passaging of virus in the presence of host-directed agents in cell culture (>P35), in many instances, viral substrains with partial but highly significant resistance phenotypes may be observed (39). Further virus propagation (up to P70) in the presence of host-directed agents did not appear to increase the magnitude of drug resistance (39). Interestingly, drug-resistant viruses maintained their phenotype upon withdrawal of the inhibitor from the cell culture medium (our unpublished data). These lines of evidence have demonstrated that resistant virus variants against host-directed agents cannot be easily generated but may still occur at a relatively low level upon long-term exposure to the host-directed agents. In this section, we will discuss the potential mechanisms that may underlie the emergence of drug resistance against host-directed antiviral agents.

TABLE 4.

Observations on development of resistance against host-directed antiviral agentsa

| Antiviral agent(s) | Virus | Host target | Mechanism of resistance | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thapsigargin | NDV | SERCA | Mutations in the fusion (F) protein | 39 |

| Amiloride (EIPA) | CVB3 | Sodium-proton exchange | Mutations close to the active center in the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | 430 |

| CGP57380 | BPXV | MNK1 | Not defined | 38 |

| DEBIO-025, SCY63, NIM811 | HCV | Cyclophilin | Mutations in the viral proteins (NS3, NS5A, and NS5B) near cyclophilin binding site | 372 |

| PIK93, BF738735, GW5074, T-00127-HEV1 | EV | PI4KB | Mutation in viral 3A protein which allows recruitment of PI4KB for synthesis of PI4P with enhanced efficiency | 481, 482 |

| Brequinar | DENV | Not defined | Mutations in the viral polymerase (E802Q) and envelope (M260V) proteins | 525 |

Abbreviations: BPXV, buffalopox virus; CVB3, coxsackievirus B3; DENV, dengue virus; EV, enterovirus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; NDV, Newcastle disease virus; SERCA, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase; MNK1, MAPK interacting kinase 1; PI4KB, phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIβ.

Switch to use alternate host factor(s).

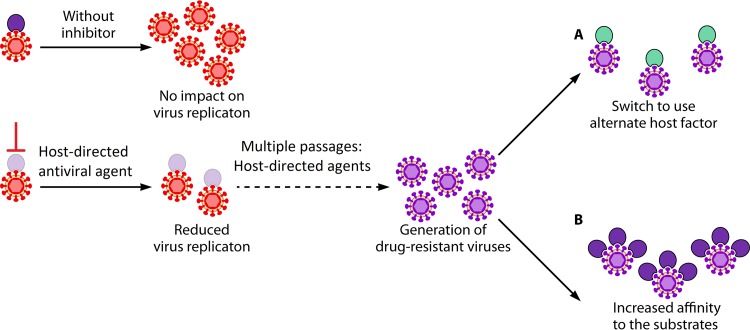

While not yet fully understood, one possible mechanism underlying the acquisition of drug resistance against host-directed agents is that the virus may switch to use an alternate host factor(s) (370) (Fig. 3A). For instance, propagation of HCV in CLDN1 knockout cells can generate CLDN1-independent HCV variants which can successfully infect and replicate in cells by using alternative host proteins—CLDN6 or CLDN9 (370).

FIG 3.

Potential mechanisms underlying acquisition of resistance against host-directed antiviral agents. Three possible mechanisms that may be associated with acquisition of resistance against host-directed antiviral agents have been hypothesized. (A) Switch to use alternate host factor. Long-term restricted availability of a critical cellular factor may induce the virus to use an alternate host factor to become resistant. (B) Increased affinity to substrates. If viruses are cultured long term in the presence of restricted availability of a particular host factor, they may increase their efficiency to optimally replicate under a limiting amount of the targeted host protein.

Other examples include viruses that have evolved diverse strategies to modulate host translational apparatus. For example, many RNA viruses can disrupt (inactivate) cellular eIF4F to shut down initiation of cap-dependent translation of cellular proteins (37). However, they initiate their own mRNA translation via a cap-independent process that involves the internal ribosome entry site (IRES). In most DNA viruses and in a few RNA viruses, viral translation involves a cap-dependent mechanism, and this is mediated via the ERK/MNK1/eIF4E pathway (37). Activated MNK1 interacts with elF4G in the initiation complex and phosphorylates elF4E, which eventually binds to the 5′ cap of the mRNA to initiate translation (37). Prolonged passaging of BPXV in cell culture in the presence of chemical inhibitors targeting MNK1 or eIF4E has resulted in the generation of mutant viruses that are resistant to MNK1 or eIF4E inhibitor (38). While the exact molecular mechanism(s) of resistance remains unknown, it is tempting to suggest that the resistant virus may have switched to use an alternate host factor(s). Alternatively, it is possible that BPXV may switch to use an alternate (cap-independent) pathway of translational initiation (371). More work needs to be done to examine these possibilities.

Another example involves SERCA, which is a key cellular factor to support Newcastle disease virus (NDV) entry as well as synthesis and the subcellular localization of viral proteins (39). NDV mutants that efficiently replicate in the presence of SERCA inhibitor (thapsigargin) have emerged at ∼P40 in cell culture, although completely drug-resistant phenotypes have not been observed (39). At least one drug resistance-associated mutation (E104K) in the F protein of the mutant virus has been identified. Additional studies on recombinant NDVs that carry a point mutation(s) in either the F gene and/or other viral proteins are necessary in order to precisely uncover the molecular mechanism(s) underlying acquisition of drug resistance against thapsigargin.

Enhanced viral efficiency under selective pressure.

If viruses are cultured long term in the presence of restricted availability of a particular host factor, they may increase their efficiency to optimally replicate under limiting amounts of the drug-targeted host proteins (Fig. 3B). For example, depletion of cellular cyclophilin, a protein essential for HCV replication, results in reduced virus replication. However, long-term viral passage generates drug-resistant HCV variants that can replicate efficiently in cyclophilin-depleted cells. The resistant HCVs appear to have acquired mutations in their NS3, NS5A, and NS5B proteins, which show their higher affinity toward cyclophilin. This allows the resistant HCV strains to replicate optimally under limiting cyclophilin concentrations (372).

Phosphatidylinositol-4 kinase III β (PI4Kβ) can be a host target for enterovirus drug development (373). However, viral resistance mutations (G5318A or A70T) in the poliovirus 3A protein results in efficient virus growth in culture in the presence of the PI4Kβ inhibitor. Those virus mutants induce increased basal levels of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P) lipid, which permits efficient viral replication in cell cultures depleted of PI4P (374). Interestingly, PI4Kβ-resistant coxsackievirus B3 mutants (3A-H57Y) can replicate in the presence of the PI4Kβ inhibitor without restoring high PI4P levels in the cell (375). This indicates that some mutation(s) in the coxsackievirus 3A genome can confer the resistance phenotype independent of PI4Kβ activation or PI4P lipid concentration. Likewise, cyclosporine (CsA)-resistant HCV mutants have also been identified in cell culture in the presence of CsA inhibitors (376, 377).

Synchronization of viral life cycle with patterns of antiviral drug therapy.

Some bacteriophages have evolved in such a way that the length of their life cycle is a mutable trait (378–383). Similarly, in bacteria, antibiotic tolerance (instead of resistance) is a process of temporarily surviving under high drug concentrations (384). The tolerance phenotype can result from mutations and may be heritable. It may involve changes in the timing of various steps of the life cycle of the organism (385, 386).

The most commonly understood mechanism of antiviral drug resistance against virus-directed therapies is that mutations occur in the viral genome at druggable sites and that these alter viral susceptibility to the direct action of drugs. However, in 2000, Wahl and Nowak proposed the term “cryptic resistance,” which defines virus populations that have become resistant without acquiring mutations at the druggable sites (387). This hypothesis was based on the fact that the concentration of antiviral drug in patients is not necessarily constant during treatment, because treatments are administered at timed intervals, with drugs being metabolized regularly. Between the administrations of two doses, the concentration of the drug may diminish to noninhibitory levels. This “cryptic resistance” phenotype describes a situation where the virus may adapt its life cycle to replicate during the periods of lowest drug concentration so as to permit sustained viral replication. However, this notion has not been formally proven. Therefore, in order to differentiate between the ability of the virus to grow in sustained (drug-resistant) versus transiently (drug-tolerant) high drug concentrations, the “cryptic resistance” terminology has been modified to “drug tolerance by synchronization” (388). Using a mathematical model, Neagu and colleagues (388) showed adaptation of the viral life cycle in response to drug treatment, a process they have referred to as “synchronization of viral life cycle with patterns of antiviral drug therapy” as a mechanism of viral drug tolerance. This effect is feasible when the times of drug dosing and viral life cycle are closely matched (388). However, this idea is based on in silico mathematical modeling and therefore needs empirical evidence in the laboratory and/or clinical settings. Moreover, the precise nature of host factors that may regulate the phenomenon of drug tolerance remains elusive. In addition, model systems are required to evaluate drug resistance/synchronization under complex and dynamic settings, such as drug combinations, multiple viral infections (214), and seasonality.

Translation into In Vivo Settings

A point of contention is that host-directed therapies are artifacts of in vitro conditions but have little translational applications (389). For example, VX-497, an IMP dehydrogenase (IMPDH) inhibitor, can impair HCV replication in vitro but not in vivo (390–392). This might occur because the nature and availability of nucleotides may differ under in vitro and in vivo conditions, thereby affecting the antiviral potency of the IMPDH inhibitor (368). Another example involves statins, which can have potent anti-HCV activity in vitro (390, 391, 393–395) but no clinical efficacy (396–399). This might partly be explained by statin activity being blocked in vivo due to its interaction with cholesterol.

Since host-directed agents interfere with host cell metabolism, a greater risk of cytotoxicity may be expected. As mentioned previously, while PI4Kβ inhibitors are known to exert potent antiviral activity against enteroviruses, they may prove to be lethal in mice, preventing their further development as antiviral drugs (400). Treating acute viral infections encounters fewer problems than treating chronic infections when host-directed agents are used (401). This is because a large number of host-directed compounds have inherent cellular toxicity problems if they are used for an extended period of time against chronic viral diseases. That being said, the majority of host-directed drugs that are in clinical use against cardiovascular and inflammatory diseases or cancers have minimal or no adverse side effects (402). For example, erlotinib (epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR] inhibitor), an FDA-approved drug for non-small-cell lung cancer, is safe and well tolerated in patients with lung cancer (403). Similarly, clinically approved host-directed HIV-1 entry inhibitors have exhibited no reported adverse reactions (404). Nevertheless, the potential safety issue of host-directed antiviral agents remains a major concern and needs to be critically analyzed.