Abstract

Bioflavonoids are of great interest due to their health-benefitting properties and possible protection against certain types of diseases. A microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) method was investigated for maximum retention of total bioflavonoids from Albizia myriophylla bark (AMB). Response surface methodology (RSM) using central composite design were employed for obtaining the best possible combination of MAE process parameters including microwave power (400–900 W), liquid/solid ratio (20–40 ml/g), extraction time (20–40 min) and ethanol concentration (60–100%). Optimum conditions of extraction under which predicted maximum bioflavonoids yield of 152.74 mg QE/g DW and antioxidant activity of 75.33% in close proximity with the experimental values were: microwave power 728 W, liquid/solid ratio 24.70 ml/g, extraction time 39.86 min and ethanol concentration 70.36%. Satisfactory statistical parameters (R2), ANOVA for the model and lack-of-fit testing provided an adequate mathematical description of the MAE of bioflavonoids with high antioxidant activity. Therefore, MAE of AMB using RSM could be termed as a time-saving and an efficient method resulting to high yield with increased antioxidant activity. Also, HPLC analysis of AMB revealed the presence of bioflavonoids viz., naringin, quercetin and apigenin; which may be further extensively studied for use as therapeutics against various health issues.

Keywords: Albizia myriophylla bark, Bioflavonoids, Microwave extraction, Response surface methodology, HPLC

Introduction

Albizia spp. is a leguminous plant categorized under the fabaceae family, and it is scattteredly grown in the wet and semi-evergreen regions of Manipur. Albizia plants are used therapeutically for insomnia, irritability, wounds, as antidysentric, antiseptic, antitubercular, etc. in traditional Indian and Chinese medicine (Mangang and Deka 2018). This genus have been confirmed to exhibit a broad pharmacological effects, including immunomodulatory, anticancer, antimalarial, antioxidant, antimicrobial, anthelmintic, and anti-inflammatory activities from several experimental evidences (Joycharat et al. 2013). The treatment of inflammation-related diseases by the use of Albizia myriophylla Benth., Fabaceae was established by measuring antioxidant potential using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, 2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) free radicals, and ferric reducing antioxidant power assays as well as anti-inflammatory effect using nitrite assay and ethyl phenylpropiolate (EPP)-induced rat ear edema model. The anti-inflammatory mechanism of A. myriophylla is most probably based on its capacity to suppress nitric oxide production as well as to be free radical scavenger (Bakasataea et al. 2018). Pharmacological evidences suggested that medicinal plants may serve as valuable sources of natural medical therapies for inflammatory diseases in folk medicines as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents (Yang et al. 2017). The occurrence of flavonoids has been observed in the ethanolic extract of A. myriophylla bark in our previous study (Mangang et al. 2017a, b). Three different flavonoids namely lupinifolin, 8-methoxy-7,3′,4′-trihydroxyflavone, 7,8,3′,4′-tetrahydroxyflavone were reported to be isolated from A. myriophylla by Joycharat et al. (2013).

A considerable interest on flavonoids have aroused due to their potential beneficial effects on human health (Middleton et al. 2000). The role of flavonoids includes triggering immune response against cancer cells and regulation of the inflammatory cascade (Kale et al. 2008). Natural flavonoids were determined as potential anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agents which act as direct and indirect antioxidants (Saewan and Jimtaisong 2013). Dependable and applied methods for separation, identification and quantitative analysis of bioflavonoids have an increasing attention for the preparation of plant-based pharmaceuticals to treat various complications linked with human diseases. Flavonoids are used in a variety of nutraceutical, pharmaceutical and medicinal applications for their antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-mutagenic and anti-carcinogenic properties (Lotito et al. 2011).

Lately, an extensive interest on innovative extraction techniques enabling automation with minimal extraction times and least organic solvent consumption has been observed (Barbero et al. 2008). Among these, microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) is an adequately efficient technique, where the polar solvents in presence with solid samples are heated by microwave energy and compounds of account between the sample and the solvent are being partitioned. Many evidences were reported about the implementation of MAE of secondary metabolites from plants (Gao et al. 2006). Nevertheless, no reports on MAE of flavonoids from A. myriophylla bark have been published. Furthermore, optimization of the extraction process parameters is necessary for the maximum yield of phenolic compounds, due to many factors affecting MAE (Spigno and De Faveri 2009).

Several factors including microwave power, liquid/solid ratio, extraction time, and ethanol concentration may govern the efficacy of MAE of bioflavonoids, and their outcomes may be either independent or interactive. The interaction of the factors may be expounded by developing response surface models to enhance the efficiency and latest optimization methods can be implemented to acquire the most favorable conditions for MAE of bioflavonoids. Response surface methodology (RSM) is a statistical technique for developing, improving and optimizing processes in which a response of interest influenced by several variables is optimized (Bas and Boyaci 2007). RSM describes the effect of independent variables, solely or in combination on the processes by generating a mathematical model to analyze the effects of the independent variables. Further, the mathematical model can then be examined to establish the optimal conditions for the process after attaining an appropriate approximating model.

Central composite design (CCD) is the most popular RSM design with three groups of design points viz., (1) factorial or fractional factorial design points; (2) star points; (3) center points, which estimate the coefficients of a quadratic model. CCD gives a good estimate of experimental error (pure error) as the center points are usually repeated 4–6 times along with inclusion of star point. Adequacy of the developed predictive model increases due to the inclusion of star points in the experimental design. One of the major attributes of the CCD is that its structure lends itself to sequential experimentation. Further, the use of CCD in RSM may prove to be more productive and beneficial than the other design by virtue of investigation of the effect of all the parameters simultaneously.

In this current study, a response surface modeling in combination with central composite design was investigated and optimized the MAE process parameters (microwave power, liquid/solid ratio, extraction time, and ethanol concentration) for maximal yield of bioflavonoids with highest antioxidant activity. Moreover, HPLC analysis was performed to identify and quantify the bioflavonoids present in AMB.

Materials and methods

Materials

Albizia myriophylla bark was collected from various parts of Manipur in India (24.6637°N, 93.9063°E). All chemicals were acquired from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO.

Experimental design

The parameters analyzed during the MAE optimization were as follows: microwave power of 400–900 W, liquid/solid ratio of 20–40 ml/g; extraction time, 20–40 min; and ethanol concentration, 60–100%. Design-Expert 7.0.0 trial (Stat-Ease Inc., USA) was used as the experimental design software. In this study, central composite design was applied in combination with response surface methodology. According to the design, total 30 experiments were performed. Bioflavonoids yield and DPPH activity were the responses of the experimental design. Multiple regressions were used for analyzing data from the experimental design to fit the following second-order polynomial model.

where Y is the response function, β0 is an intercept and βi, βii, and βij are the coefficients of the linear, quadratic, and interactive terms, respectively. Correspondingly Xi, , and XiXj are the coded independent variables. The experimental design of the microwave assisted extraction (MAE) is depicted in Table 1. The responses were obtained from the mean of triplicate values. Conforming to the analysis of variance, regression coefficients of individual linear, quadratic, and interaction terms were obtained. From the regression models, statistical calculation was done to create dimensional and contour maps using the regression coefficients.

Table 1.

Experimental design with operational parameters and observed responses

| Run | X1 Microwave power (W) |

X2 Liquid/solid ratio (ml/g) |

X3 Extraction time (min) |

X4 Ethanol concentration (% v/v) |

Y1 Yield (mg/g) |

Y2 DPPH activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 400 | 20 | 20 | 60 | 39.3 | 68.2 |

| 2 | 900 | 20 | 20 | 60 | 79.3 | 67.7 |

| 3 | 400 | 40 | 20 | 60 | 27.3 | 63.5 |

| 4 | 900 | 40 | 20 | 60 | 38.0 | 60.7 |

| 5 | 400 | 20 | 40 | 60 | 64.3 | 69.9 |

| 6 | 900 | 20 | 40 | 60 | 120.3 | 73.6 |

| 7 | 400 | 40 | 40 | 60 | 18.3 | 62.3 |

| 8 | 900 | 40 | 40 | 60 | 72.7 | 61.1 |

| 9 | 400 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 8.3 | 62.7 |

| 10 | 900 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 102.0 | 68.3 |

| 11 | 400 | 40 | 20 | 100 | 10.0 | 68.0 |

| 12 | 900 | 40 | 20 | 100 | 110.3 | 71.2 |

| 13 | 400 | 20 | 40 | 100 | 47.0 | 64.7 |

| 14 | 900 | 20 | 40 | 100 | 152.0 | 75.3 |

| 15 | 400 | 40 | 40 | 100 | 33.0 | 64.3 |

| 16 | 900 | 40 | 40 | 100 | 148.7 | 71.8 |

| 17 | 400 | 30 | 30 | 80 | 32.3 | 67.1 |

| 18 | 900 | 30 | 30 | 80 | 146.0 | 69.6 |

| 19 | 650 | 20 | 30 | 80 | 95.0 | 74.4 |

| 20 | 650 | 40 | 30 | 80 | 78.3 | 73.0 |

| 21 | 650 | 30 | 20 | 80 | 135.3 | 72.5 |

| 22 | 650 | 30 | 40 | 80 | 137.0 | 73.6 |

| 23 | 650 | 30 | 30 | 60 | 133.3 | 71.7 |

| 24 | 650 | 30 | 30 | 100 | 140.0 | 74.4 |

| 25 | 650 | 30 | 30 | 80 | 136.0 | 74.8 |

| 26 | 650 | 30 | 30 | 80 | 124.0 | 73.3 |

| 27 | 650 | 30 | 30 | 80 | 139.0 | 74.2 |

| 28 | 650 | 30 | 30 | 80 | 130.0 | 73.0 |

| 29 | 650 | 30 | 30 | 80 | 125.0 | 72.8 |

| 30 | 650 | 30 | 30 | 80 | 137.0 | 73.5 |

Optimization by RSM

The standard response surface methodology (RSM) was used for the optimization of the developed model.

Verification of model

RSM was used to attain the optimal conditions depending on the microwave power, liquid/solid ratio, extraction time and ethanol concentration. Under optimal conditions, the extraction of bioflavonoids was performed and yield was determined. The validity of the model was found by comparing the experimental and predicted values.

Extraction of bioflavonoids from A. myriophylla bark

Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE)

MAE was carried out using a laboratory scale Microwave Gravity Station (Milestone, NEOS-GR, Germany) with a digital controlled system for temperature, time and power. The experimental domain was described by taking the operative limits of the instrument and preliminary experiments into account. Accordingly, the experimental design was followed to carry out an efficient extraction. After method optimization, extraction was performed under optimized operational conditions. The final extract was used for further analysis.

Determination of bioflavonoids content

Bioflavonoids content was determined by the AlCl3colorimetric method (Bag et al. 2015). An ethanolic extract solution (1 ml) was mixed with 1 ml of 2% methanolic AlCl3.6H2O. Absorbance was measured at 415 nm after equilibrating for 10 min. Concentration of total flavonoids in the samples was then estimated by comparing to a quercetin standard curve. The concentrations were shown in mg quercitin/g of powder on dry weight basis (mg QE/g DW).

DPPH radical scavenging assay

The antioxidant activity of AMB was measured with slight modifications of the method described by Alam et al. (2013). To 0.2 ml of AMB, 2 ml of DPPH solution (0.5 mM) in ethanol was added and incubated in the dark. After 20 min, the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. Ethanol was used in place of DPPH solution for blank. The antioxidant activity was calculated using the equation as given below:

where A0 is the absorbance before reaction and A1 is the absorbance after reaction has taken place.

HPLC analysis

A HPLC system (Ultimate 3000, Dionex, USA) was used for the analysis, with a UV detector for detection at 265 nm and Acclaim 120® C18 column (5 μm beads size; 120 Å; 4.0 × 250 mm) maintained at 30 ºC. The extract was estimated for bioflavonoids after diluting 100-fold with deionized water, adjusted to pH 7.0, filtered through 0.2 μm syringe filter and then injected (20 μl) to pass through two C18 Sep Pak® cartridges in series preconditioned with methanol. The mobile phase used are Eluent A—acidified DW (adjusted to 2.64 pH with diluted HCl) and Eluent B—acidified DW:acetonitrile (20:80). For elution, a gradient run at a constant flow rate of 1.5 ml/min was used. Identification of bioflavonoids was performed by comparing their HPLC retention times and their UV spectrums with that of authentic analytical standards. External standards were used for the quantification (Lee 2000).

Results and discussion

Response surface modeling

The experimental conditions and corresponding responses according to the experimental design is shown in Table 1. The regression equations created after the response surface regression (RSREG) procedure is given as follows:

Interactive effects of various factors on bioflavonoids yield

The response surface plot in Fig. 1a depicts that increasing microwave power gives higher yield of bioflavonoids. The influences of microwave power on the bioflavonoids yield were analyzed at levels of 400–900 W with different solvent concentration (40–60% ethanol), extraction time (20–40 min) and liquid/solid ratio (20:1–40:1 ml/g). A prominent rise in the bioflavonoids yield from 140 to 152 mg QE/g DW was shown at power levels of 650–900 W (Fig. 1a). The bioflavonoids yield is greatly influenced by liquid/solid ratio which is one of the important parameter for most of the extraction techniques. For instance, it is necessary to increase the yield in an industrial extraction process, while minimizing the solvent consumption (Spigno and De Faveri 2009). In the current study, the bioflavonoids yield was decreased during extraction with higher liquid/solid ratio (Fig. 1a). A rise in the liquid/solid ratio leading to a slight decrease in the flavonoids content depicts a saturated condition.

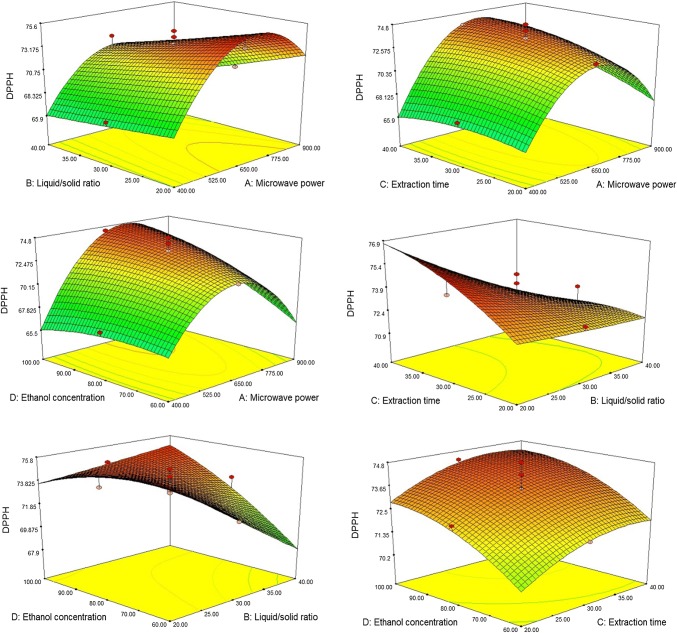

Fig. 1.

Response surface plots showing the effects of operational parameters on total bioflavonoids yield: a microwave power and liquid/solid ratio, b microwave power and extraction time, c ethanol concentration and microwave power, d extraction time and liquid/solid ratio, e ethanol concentration and liquid/solid ratio, f extraction time and ethanol concentration

In Fig. 1b, the surface plot displays the interaction of microwave power and extraction time on the bioflavonoids yield. An increased extraction time generally maximizes the quantity of analytes, even though there is a probability of extracted compounds degradation. In this current work, the bioflavonoids yield was analysed at different extraction times (20–40 min) alongwith variations in three other factors: ethanol, microwave power level, and liquid/solid ratio. The outcomes indicated that the bioflavonoids yield increased with higher irradiation time from 146 mg QE/g in 30 min to 152 mg QE/g in 40 min. A remarkable increase in the bioflavonoids yield was also noted with the increasing microwave power (Fig. 1b). The findings of Ballard et al. (2010) resembled our results. The results from our study emphasized an irradiation time of 39.86 min to be used for further experimentation using MAE. A continuous higher temperature was obtained in the extraction system with more microwave power and prolonged irradiation time. This interactive effect of temperature and time enhanced the solubility of bioflavonoids and decreased the viscosity of extraction solvent, eventually increasing the release and dissolution of these compounds. Nevertheless, certain bioflavonoids can be degraded due to high temperatures. A noteworthy influence of the combined effect of extraction time and microwave power on the bioflavonoids recovery was also observed.

The surface plot in Fig. 1c displays interactive positive impacts of ethanol concentration and microwave power on the response parameter (Y1). A parabolic increase of bioflavonoids recovery within the range of 60–100% ethanol concentration was observed. The yield in the extraction medium maximized with increase in ethanol concentration. Water is a strong polar solvent miscible in any fraction, whereas ethanol is a low-polar solvent (Zhang et al. 2007). Water addition in ethanol continuously increases polarity of the complex solvent (Zhang et al. 2008). In our study, the experimental value (yield) was higher than the predicted value, with relatively well microwave energy absorption at 70.36% ethanol (Table 4). For the optimization design, ethanol fraction in the extraction solvent was monitored within the range of 60–100%. The optimum extraction power, time and liquid/solid ratio was determined with reference to solvent with 70.36% ethanol content.

Table 4.

Optimized conditions for microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) of bioflavonoids from A. myriophylla bark

| Microwave power (W) | Liquid/solid ratio (ml/g) | Extraction time (min) | Ethanol concentration (%) | Responses | Predicted value | Experimental value | % Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 728 | 24.70 | 39.86 | 70.36 | Yield (mg QE/g DW) | 152.74 | 156.81 | 2.60 |

| DPPH activity (%) | 75.33 | 76.14 | 1.06 |

In Fig. 1d, the response surface plot depicts the interaction of extraction time and liquid/solid ratio on the bioflavonoids recovery. The maximization of bioflavonoids recovery with more extraction time and the minimization with higher liquid/solid ratio were noticed. Bioflavonoids recovery was maximum at extraction time of 39.86 min and liquid/solid ratio of 24.70 ml/g. The lesser heating effect under microwave conditions and the solubility of bioflavonoids results to mass transfer decelerated by more liquid/solid ratio which eventually affects the yield of bioflavonoids. The synergistic effect of other parameters involved may be the reason for the increase in bioflavonoids yield. In a similar report by Chen et al. (2007), 2 h was shown as the optimal extraction time for the extraction of a hypotensive drug geneposide from Eucommia ulmoides bark.

The increasing bioflavonoids recovery with higher ethanol concentration and a parabolic decrease of the yield with effect to liquid/solid ratio is shown in Fig. 1e. Hayat et al. (2009) explained that extraction yield can be maximized and promote swelling of cell material respectively with more contact surface area between plant matrix and solvent, favourably enhanced by ethanol and water.

The interactive response surface plot of extraction time and ethanol concentration displays positive increase in response variable (Y1) with their increasing values (Fig. 1f). According to Luque de Castro and Tena (1996), a rapid diffusion of flavonoids into the ethanol solution is most probably promoted through non-covalent interactions. Optimum extraction yield may be achieved when there is a coincidence in the polarity of solvent and bioflavonoids.

Interactive effects of various factors on antioxidant activity

In the 3D response surface plots (Fig. 2), the interactive effects of different independent factors on the antioxidant activity of AMB are shown. Maximum DPPH radical scavenging activity of 75.3% was shown under the extraction conditions of 900 W microwave power, 20 ml/g liquid/solid ratio, 40 min extraction time and 100% ethanol concentration. Liquid/solid ratio had a negative linear effect on the antioxidant activity. During the MAE process, an increase in the liquid/solid ratio led to decrease in antioxidant activity from highest value of 75.3% to least value of 60.7%. As the microwave power increases, an increasing trend of the antioxidant activity to a certain point and slightly decreasing at the end was observed. At the highest microwave power, thermal degradation and oxidation of antioxidants may have occurred leading to reduced antioxidant activity (Zekovic et al. 2016).

Fig. 2.

Response surface plots showing the effects of operational parameters on DPPH activity: a microwave power and liquid/solid ratio, b microwave power and extraction time, c ethanol concentration and microwave power, d extraction time and liquid/solid ratio, e ethanol concentration and liquid/solid ratio, f extraction time and ethanol concentration

The interaction between liquid/solid ratio and microwave power had a significant negative influence on antioxidant activity. It can be seen that the antioxidant activity increased significantly with more extraction time. This positive linear effect of extraction time confirmed that a prolonged extraction time is required for complete extraction of bioflavonoids and subsequently exhibiting maximum antioxidant activity. Similar reports showing increased polyphenol yield with increasing extraction time were given by Zhang et al. (2011). A significant effect of the interaction between microwave power and extraction time on the antioxidant activity was observed. Ethanol concentration showed a positive effect on the antioxidant activity. The positive effect of ethanol concentration and microwave power means that antioxidant activity will decrease significantly at higher level of the variables.

Optimization of MAE conditions

Modeling and fitting the model using response surface methodology (RSM)

The experimental design and respective responses for the total bioflavonoids yield from A. myriophylla bark and the antioxidant activity are depicted in Table 1. The regression coefficients of intercept, linear, quadratic and interaction terms of the model were calculated and given in Tables 2 and 3 (Zhang et al. 2013). It was revealed that all the four linear parameters, microwave power (X1), liquid/solid ratio (X2), extraction time (X3) and ethanol concentration (X4); quadratic parameters of X1 and X2; and the interaction parameters X1X4 and X2X4 showed significant effect on the bioflavonoids yield at P < 0.05, while quadratic parameters of X3 and X4 and the interaction parameters X1X2, X1X3, X2X3 and X3X4 were found insignificant (P > 0.1). In addition, significant effect on the antioxidant activity was shown by linear terms of independent variables (X1, X3 and X4); quadratic variables of X2; and the interaction variables X1X3, X1X4 and X2X4 at P < 0.05, whereas linear variable (X2); quadratic variables of X1, X3 and X4; and interaction variables X1X2, X2X3 and X3X4 were the insignificant terms (P > 0.1). Hence, the non-significant parameters (P > 0.1) were discounted.

Table 2.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of fitted model for total bioflavonoids yield (Y1)

| Parameter | Estimated coefficients | Sum of squares | DF | F value | Prob > F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 66,424.19 | 14 | 39.81* | < 0.0001 | Significant | |

| Linear | ||||||

| X1 | 38.31 | 26,411.68 | 1 | 221.62* | < 0.0001 | |

| X2 | − 9.49 | 1622.601 | 1 | 13.62* | 0.0022 | |

| X3 | 13.53 | 3294.014 | 1 | 27.64* | < 0.0001 | |

| X4 | 8.81 | 1395.681 | 1 | 11.71* | 0.0038 | |

| Quadratic | ||||||

| − 38.80 | 3900.987 | 1 | 32.73* | < 0.0001 | ||

| − 41.30 | 4419.851 | 1 | 37.09* | < 0.0001 | ||

| 8.20 | 174.1009 | 1 | 1.46 | 0.2455 | ||

| 8.70 | 195.9873 | 1 | 1.64 | 0.2192 | ||

| Interaction | ||||||

| X1X2 | − 0.85 | 11.56 | 1 | 0.10 | 0.7597 | |

| X1X3 | 5.40 | 466.56 | 1 | 3.91 | 0.0665 | |

| X1X4 | 15.85 | 4019.56 | 1 | 33.72* | < 0.0001 | |

| X2X3 | − 4.23 | 285.61 | 1 | 2.40 | 0.1424 | |

| X2X4 | 8.73 | 1218.01 | 1 | 10.22* | 0.0060 | |

| X3X4 | 3.65 | 213.16 | 1 | 1.79 | 0.2010 | |

| Lack of fit | 1580.81 | 10 | 3.82 | 0.0760 | Not significant | |

| R-squared value | 0.9738 | |||||

| Adj R-squared value | 0.9493 |

*Significant values

Table 3.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of fitted model for DPPH activity (Y2)

| Parameter | Estimated coefficients | Sum of squares | DF | F value | Prob > F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 591.60 | 14 | 79.33* | < 0.0001 | Significant | |

| Linear | ||||||

| X1 | 1.60 | 46.19 | 1 | 86.71* | < 0.0001 | |

| X2 | − 1.59 | 45.64 | 1 | 85.67* | < 0.0001 | |

| X3 | 0.78 | 11.01 | 1 | 20.68* | 0.0004 | |

| X4 | 1.22 | 26.90 | 1 | 50.50* | < 0.0001 | |

| Quadratic | ||||||

| − 0.79 | 10.08 | 1 | 18.92* | 0.0006 | ||

| 0.94 | 14.24 | 1 | 26.73* | 0.0001 | ||

| 1.73 | 47.96 | 1 | 90.03* | < 0.0001 | ||

| − 1.28 | 26.15 | 1 | 49.09* | < 0.0001 | ||

| Interaction | ||||||

| X1X2 | 2.26 | 81.45 | 1 | 152.90* | < 0.0001 | |

| X1X3 | − 0.06 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.10 | 0.7607 | |

| X1X4 | − 5.33 | 73.63 | 1 | 138.22* | < 0.0001 | |

| X2X3 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.9099 | |

| X2X4 | − 0.63 | 1.03 | 1 | 1.94 | 0.1844 | |

| X3X4 | − 0.65 | 1.08 | 1 | 2.03 | 0.1748 | |

| Lack of fit | 5.09 | 10 | 0.88 | 0.5992 | Not significant | |

| R-squared | 0.986674 | |||||

| Adj R-squared | 0.974236 |

*Significant values

The model F-values of 39.81 (Y1) and 79.33 (Y2) shown in the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the experimental outcomes indicates the significance of the model (Tables 2 and 3). A probability of only 0.01% (Y1 and Y2) for the occurrence of a large "Model F-Value" due to noise was predicted. Sample variations of 97.38% (Y1) and 98.67% (Y2) for the MAE efficiency of AMB ascribed to the independent variables was implied by the determination coefficient (R2) of 0.9738 (Y1) and 0.9867 (Y2). However, the regression model could not always be described as sound one by the large value of R2 (Karazhiyan et al. 2011). Adj. R2 should be comparable to R2 in a good statistical model. In Tables 2 and 3, there is no great difference between R2 and R2 adj values for the model. The validity of the model is confirmed by the “Lack of Fit F-value” of 3.82 (Y1) and 0.88 (Y2) which indicates the non-significance of the Lack of Fit. Non-significant Lack of Fit is preferable for the model to fit very well. The results revealed that the model could very efficiently predict the bioflavonoids yield from A. myriophylla bark. It has been confirmed that, besides increased bioflavonoids yield, optimized MAE provides extracts with highest antioxidant activity.

Analysis of response surfaces

Three dimensional response profiles of multiple non-linear regression models were plotted in Figs. 1a–f and 2a–f to investigate the combined effects of independent variables and their mutual interaction on the response variables (Y1 and Y2). The response plots were generated by using z-axis against two different independent variables while keeping the other two independent variables at their zero level. The interactions between each two different factors on the response variables (Y1 and Y2) are depicted in Figs. 1a–f and 2a–f. From the combined depiction of Fig. 1a–f and Table 2, it can be clearly observed the linear parameters X1, X3, X4 have positive effects on the response parameter whereas X2 has a negative effect on the response parameter (Y1). In case of the quadratic parameters, and have negative impact on the response but and showed positive effects. The interactive effects of different parameters also displayed both positive as well as negative impacts on the response. The response variable was positively affected by all the interactive parameters except, X1X2 and X2X3. In Fig. 2a–f and Table 3, the positive effect of linear terms of independent variables (X1, X3 and X4); quadratic variables of X2; and the interaction variables X1X3, X1X4 and X2X4 on the response variable (Y2) has been distinctly shown. The linear variable (X2); quadratic variables of X1, X3 and X4; and interaction variables X1X2, X2X3 and X3X4 showed insignificant effects on the response variable (Y2). The interactive effect of extraction power and time on the recovery of bioflavonoids using microwave energy was found to be prominent. Hayat et al. (2009) described microwave power as one of the main variables of microwave-assisted extraction, rupturing the cell wall which affects the release of polyphenols from different matrices and also having the ability to modify equilibrium and mass transfer conditions during extraction. Polyphenols extraction was accelerated with the maximization of microwave power. Also, it has been confirmed that prolonged extraction time is required for complete extraction of polyphenols and subsequently showing increased polyphenols yield with maximum antioxidant activity (Zhang et al. 2011).

Validation and verification of predictive model

The critical values of 70.36% ethanol concentration, 728 W microwave power, 39.86 min extraction time and liquid/solid ratio of 24.70 ml/g resulted to the stationary point for a maximum MAE efficiency (optimal conditions of MAE) of bioflavonoids (Table 4). The above optimal conditions were used to predict the optimum response values by testing the appropriateness of the model equation. The accuracy of the model was confirmed by conducting a verified experiment under the optimal conditions. Non-significant difference (P > 0.05) was observed between the predicted extraction yield of bioflavonoids (152.74 mg QE/g DW) and experimental values (156.81 mg QE/g DW). Similar phenomenon of close proximity of the predicted (75.33%) and experimental values (76.14%) of the antioxidant activity was shown. In the methodology adopted, the normal probability at residuals implied no abnormality which was determined from the preliminary data. These results indicated that the response model is sufficient to define the good correlation between the theoretical optimization and experimental value. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2013) also confirmed the adequacy of the response of regression model to reflect the expected optimization from the strong correlation between the real and predicted results. From the analysis, it has been demonstrated that microwave-assisted extraction of total bioflavonoids from A. myriophylla bark was a time-saving and efficient method resulting to high yield with maximum antioxidant activity.

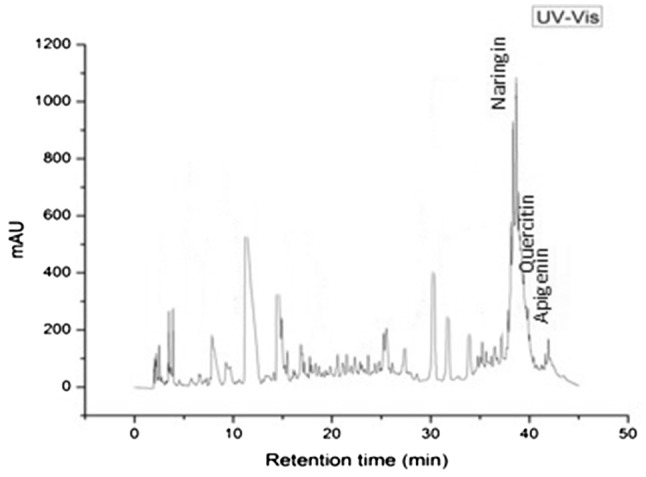

HPLC analysis

HPLC analysis was performed for the identification and quantification of different bioflavonoids. Retention times and calibration curve of external standards were taken into account for the analysis (Fig. 3). Three flavonoids namely; naringin, quercetin and apigenin were detected in AMB; where content of naringin with 18.736 mg QE/g DW was observed to be highest followed by quercetin (0.573 mg QE/g DW) and apigenin (0.295 mg QE/g DW), respectively (Table 5). Naringin was termed as natural flavanone glycosides with a range of biological activities (Zhang et al. 2012). Highest content of naringin with 27.00 mg/g DW was found in Huyou fruit. Purified naringin were identified by HPLC and showed the possibility of its use as a potential hypoglycaemic agent through regulation of glucose metabolism. In a study by Giannuzzo et al. (2003), naringin was detected as the major compound at the peak of 2 min retention time associated with the injection solvent. Total quercetin in onion sample was presented as the concentration of free quercetin and different forms of quercetin existing in conjugation with carbohydrates (Huma et al. 2009). Quantification of all these compounds was performed by comparing the retention time and absorbance of peaks at 360 nm with the use of authentic standards.

Fig. 3.

HPLC chromatogram showing the detection of bioflavonoid compounds namely, naringin, quercetin and apigenin in Albizia myriophylla extract

Table 5.

Bioflavonoids content in A. myriophylla bark extract

| Bioflavonoid | Retention time (min) | Concentration (mg QE/g DW) |

|---|---|---|

| Naringin | 38.47 | 18.736 |

| Quercetin | 39.81 | 0.573 |

| Apigenin | 40.43 | 0.295 |

Conclusion

The present work is the development of an optimized condition for microwave-assisted extraction of bioflavonoids from A. myriophylla bark. The process parameters, including microwave power, extraction time, liquid/solid ratio and ethanol concentration were optimized for better bioflavonoids extraction using RSM, which have been demonstrated as an effective and easy approach to obtain the optimal combination. The optimal conditions were determined to be: microwave power 728 W, liquid/solid ratio 24.70 ml/g, extraction time 39.86 min and ethanol concentration 70.36%. Under these conditions, the predicted values of bioflavonoids yield and antioxidant activity from the model results was found to be 152.74 mg QE/g DW and 75.33%, which was subsequently confirmed by experimental results. These results demonstrated the significant efficiency of response model to define the good correlation between the theoretical optimization and experimental value. From the satisfactory statistical parameters (R2) and ANOVA for the model and lack-of-fit testing, it could be concluded that a second-order polynomial model provided an adequate mathematical description of the MAE of bioflavonoids with high antioxidant activity. Therefore, RSM could be successfully applied for optimization for maximized bioflavonoids yield with increased antioxidant activity. Moreover, microwave-assisted extraction of total bioflavonoids from A. myriophylla bark could be concluded as a time-saving and efficient method resulting to high yield with maximum antioxidant activity. Also, HPLC analysis of AMB revealed the presence of naringin, quercetin and apigenin. The bioflavonoids in AMB which are known to possess potential therapeutic properties may be further extensively studied for use as therapeutics against various health issues.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alam MN, Bristi NJ, Rafiquzzaman M. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharm J. 2013;21:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bag GC, Devi PG, Bhaigyabati T. Assessment of Total Flavonoid content and antioxidant activity of methanolic rhizome extract of three Hedychium species of Manipur valley. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2015;30:154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Bakasataea N, Kunworaratha N, Yupanquib CT, Voravuthikunchaic SP, Joycharat N. Bioactive components, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities of the wood of Albizia myriophylla. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2018;28:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.bjp.2018.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard TS, Mallikarjunan P, Zhou K, O’Keefe S. Microwave-assisted extraction of phenolic antioxidant compounds from peanut skins. Food Chem. 2010;120:1185–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.11.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbero GF, Liazid A, Palma M, Barroso CG. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of capsaicinoids from peppers. Talanta. 2008;75:1332–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2008.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bas D, Boyaci IH. Modeling and optimization I: usability of response surface methodology. J Food Eng. 2007;78:836–845. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Xie MY, Gong XF. Microwave-assisted extraction used for the isolation of total triterpenoid saponins from Ganoderma atrum. J Food Eng. 2007;81:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2006.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Song BZ, Liu CZ. Dynamic microwave-assisted extraction of flavonoids from Saussurea medusa maxim cultured cells. Biochem Eng J. 2006;32:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2006.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giannuzzo AN, Boggetti HJ, Nazareno MA, Mishima HT. Supercritical fluids extraction of naringin from the peel of Citrus paradise. Phytochem Anal. 2003;14:221–223. doi: 10.1002/pca.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayat K, Hussain S, Abbas S, Farooq U, Ding B, Xia S, Jia C, Zhang X, Xia W. Optimized microwave-assisted extraction of phenolic acids from citrus mandarin peels and evaluation of antioxidant activity in vitro. Sep Purif Technol. 2009;70:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2009.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huma Z, Vian MA, Maingonnat JF, Chemat F. Clean recovery of antioxidant flavonoids from onions: Optimising solvent free microwave extraction method. J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216:7700–7707. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joycharat N, Thammavong S, Limsuwan S, Homlaead S, Voravuthikunchai SP, Yingyongnarongkul B. Antibacterial substance from Albizia myriophylla wood against cariogenic Streptococcus mutans. Arch Pharm Res. 2013;36:723–730. doi: 10.1007/s12272-013-0085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale A, Gawande S, Kotwal S. Cancer phytotherapeutics: role for flavonoids at the cellular level. Phytother Res. 2008;22:567–577. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karazhiyan H, Razavi S, Phillips GO. Extraction optimization of a hydrocolloid extract from cress seed (Lepidium sativum) using response surface methodology. Food Hydrocoll. 2011;25:915–920. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.08.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS. HPLC analysis of phenolic compounds. In: Nollet LML, editor. Food analysis by HPLC. 2, Revised and Expanded. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 2000. pp. 775–824. [Google Scholar]

- Lotito SB, Zhang WJ, Yang CS, Crozier A, Frei B. Metabolic conversion of dietary flavonoids alters their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque de Castro MD, Tena MT. Strategies for supercritical fluid extraction of polar and ionic compounds. Trends Anal Chem. 1996;15:32–37. doi: 10.1016/0165-9936(96)88035-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mangang KCS, Deka SC. Bioflavonoids from Albizia myriophylla: its immunomodulatory effects. In: Aguilar CN, Carvajal-Millan E, editors. Applied Food Science and Engineering with Industrial Applications. Boca Raton: International Apple Academic Press Inc, Taylor and Francis Group; 2018. pp. 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mangang KCS, Das AJ, Deka SC. Comparative shelf life study of two different rice beers prepared using wild-type and established microbial starters. J Inst Brew. 2017;123:579–586. doi: 10.1002/jib.446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mangang KCS, Das AJ, Deka SC. Shelf-life improvement of rice beer by incorporation of Albizia myriophylla extracts. J Food Process Preserv. 2017 doi: 10.1111/jfpp.12990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton E, Jr, Kandaswami C, Theoharides TC. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:673–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewan N, Jimtaisong A. Photoprototection of natural flavonoids. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2013;3:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Spigno G, Faveri DMD. Microwave-assisted extraction of tea phenols: a phenomenological study. J Food Eng. 2009;93:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2009.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R, Yuan BC, Ma YS, Zhou S, Liu Y. The anti-inflammatory activity of locorice, a widely used Chinese herb. Pharm Biol. 2017;55:5–18. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2016.1225775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zekovic Z, Vladic J, Vidovic S, Adamovic D, Pavlic B. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) of coriander phenolic antioxidants–response surface methodology approach. J Sci Food Agric. 2016;96:4613–4622. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Li D, Wang L, Ozkan N, Chen XD, Mao Z, Yang H. Optimization of ethanol-water extraction of lignans from flaxseed. Sep Purif Technol. 2007;57:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2007.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Yang R, Liu C. Microwave-assisted extraction of chlorogenic acid from flower buds of Lonicera japonica Thunb. Sep Purif Technol. 2008;62:480–483. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2008.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HF, Yang XH, Wang Y. Microwave assisted extraction of secondary metabolites fromplants: current status and future directions. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2011;22:672–688. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2011.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Sun C, Yan Y, Chen Q, Luo F, Zhu X, Li X, Chen K. Purification of naringin and neohesperidin from Huyou (Citrus changshanensis) fruit and their effects on glucose consumption in human HepG2 cells. Food Chem. 2012;135:1471–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Hu M, He L, Fu P, Wang L, Zhou J. Optimization of microwave-assisted enzymatic extraction of polyphenols from waste peanut shells and evaluation of its antioxidant and antibacterial activities in vitro. Food Bioprod Process. 2013;91:158–168. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2012.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]