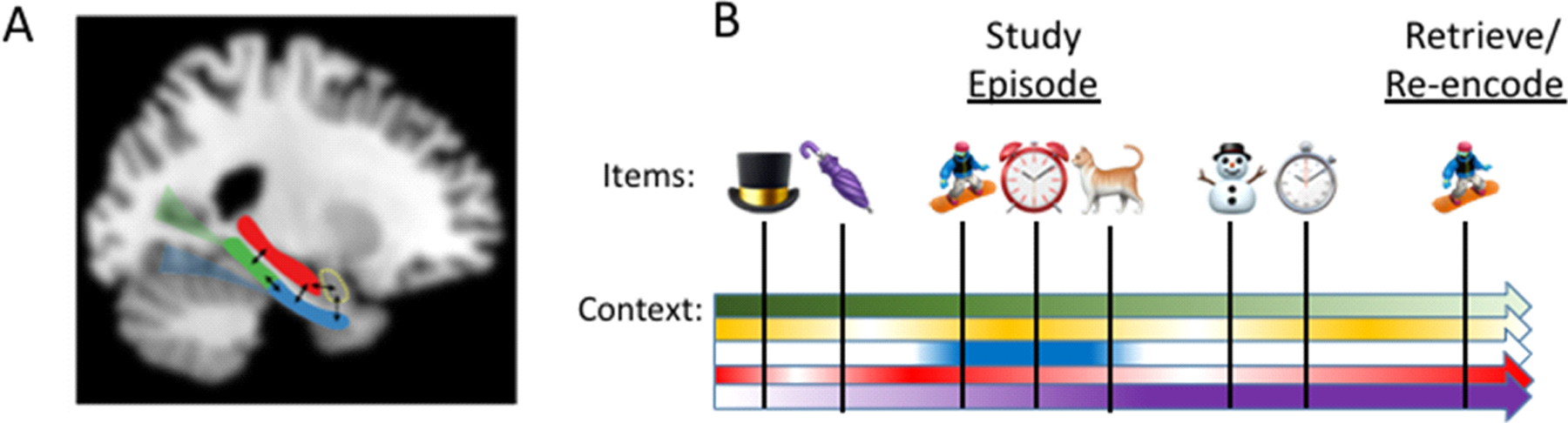

Fig. 1 |. Contextual binding theory.

a | Contextual binding theory assumes that the hippocampus (red) is necessary for episodic memory because it binds together the item and context information that makes up the study event. The hippocampus receives information from various regions including the perirhinal cortex and the ventral ‘what’ stream, and is thought to provide information about the items in an event (e.g., objects and people), the amygdala (dotted yellow) which provides information about the emotional aspects of the event, and the parahippocampal cortex (green) which receives spatial information from the dorsal ‘where’ stream. The regions outside the hippocampus are assumed to support the learning of simple associations, and so can learn about regularities and occurrences in the environment, whereas the hippocampus is unique in supporting memory for individual episodes, and so is said to support complex or high-resolution bindings179, in the sense that it links together the multiple objects and detailed contextual information that makes up an event. This approach is consistent with neurocomputational models that propose that the hippocampus supports memory via a process of pattern separation and completion8,17,180. b | According to the CB model, context can reflect any aspect of the study episode that links the test item to the specific study event, such as the spatial, temporal or cognitive details of that event. Some aspects of context can change quickly like moving to a new room or initiating a new cognitive task (e.g., the blue arrow), whereas other aspects of context can change gradually like changes in the subject’s mood or changes in lighting throughout the day. Because context gradually drifts, the study event will extend in time beyond the occurrence of the study items themselves. In this way, forgetting is assumed to be due to interference from other memories that share similar content or context. That is, because episodic memory requires subjects to recollect which items (i.e., snowboarder, clock, cat) occurred in a specific experimental context (i.e., the related portion of the context arrows), other episodic memories that share a similar context to the studied items (i.e., umbrella and snowman) or that have similar content (i.e., stopwatch) will interfere with memory retrieval because they are confusable and effectively compete with each other. Importantly, because forgetting is the result of contextual interference, forgetting will be produced not only by events that occur after the study event, but also by events that occur prior to the study event (i.e., top-hat and umbrella). In addition, manipulations that reduce the encoding of interfering materials, such as allowing subjects to rest or sleep, are expected to benefit memory by reducing contextual interference. Moreover, if an item is repeated (e.g., the item may be re-studied or the initial event may be remembered) it will be re-encoded along with new context information. Finally, neural activity that is related to the encoding of the study event will be temporally extended because of the gradually changing context, such that encoding related activity will linger after the nominal study event is over (i.e., re-activation), and in fact, may even be observed prior to the onset of the study event (i.e., pre-activation).