Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV)-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma is a distinct, recently described neoplasm of salivary gland nature that has an unusual microscopic appearance exhibiting multidirectional differentiation. Originally described by Bishop et al. in 2012, this distinct form of head and neck cancer is a very rare entity that few pathologists have encountered in practice, and only 50 cases have been reported in the literature. It usually presents as a large, destructive mass confined to the nasal cavity or paranasal sinuses, and is always associated with high-risk HPV infection. Although histologically it often resembles adenoid cystic carcinoma, this neoplasm also consistently exhibits features of myoepithelial, ductal and squamous differentiation. Newly recognized characteristics have recently been described that include bizarre pleomorphism, sarcomatoid transformation, and heterologous cartilaginous differentiation. These unique features have continued to expand the morphologic spectrum of this neoplasm and justify the recent change in its nomenclature from “HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features” to “HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma (HMSC)”. In 2017, “HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic like features” was included as a provisional tumor type by the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors. Despite the presence of high-grade histologic characteristics such as necrosis and brisk mitotic activity, and a tendency for recurrence, HMSC demonstrates indolent clinical behavior and carries a good prognosis.

Keywords: HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma, Sinonasal carcinoma, Head and neck carcinoma, HPV carcinoma

Introduction

Sinonasal carcinomas account for less than 1% of all cancers and about 5% of all head and neck cancer [1]. Diagnosis of these malignancies remains a great challenge for pathologists due to the rarity and diversity of neoplasms that arise in this anatomic region [2]. Recently recognized sinonasal tract tumors include the NUT carcinoma, SMARCB1 deficient sinonasal carcinoma, biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma, renal cell-like adenocarcinoma, and human papillomavirus (HPV)-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma (HMSC), previously known as HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC)-like features [3]. The last tumor, which was initially described in 2012 by Bishop et al. [4, 5], is a unique type of malignant neoplasm only reported in the sinonasal tract. It is morphologically similar to ACC, which is the second most common sinonasal carcinoma after squamous cell carcinoma [6]. HMSC has been shown by Bishop et al. to demonstrate a broad morphologic spectrum exhibiting characteristics of both a surface-derived and salivary gland carcinoma with multidirectional phenotypes including myoepithelial, ductal, and squamous lines [7, 8]. This novel entity is also consistently associated with high-risk HPV infection, and displays an indolent clinical course as demonstrated by the small number of reported cases with clinical follow-up [8, 9]. In 2017, Bishop et al. published an expanded series of 49 cases and presented additional findings such as scattered anaplastic giant cells, squamous differentiation within the invasive tumor, an epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma-like growth, and sarcomatoid differentiation with cartilage formation [8]. Here, we present an additional case that demonstrates the typical morphologic features described for human papillomavirus-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma and review the literature on this topic.

Case Report

A 70-year-old male patient with a history of rhinitis and bilateral hearing loss presented due to right-sided nasal obstruction accompanied by facial pain, tenderness and headaches for 1 month. He also described yellow nasal drainage and recalled a recent episode of epistaxis which required packing in the emergency room. He denied any history of nasal injury or surgery. Physical examination disclosed severe edema throughout the nasal cavity and purulent material extending to the nasopharynx. The patient was diagnosed with an ongoing sinus infection and was treated with a course of antibiotics. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans of the paranasal sinuses revealed a heterogeneously enhancing large, expansile mass centered within the right nasal cavity, protruding posteriorly into the right aspect of the choana/nasopharynx, and causing leftward deviation of the nasal septum and rightward deviation of the medial wall of the right maxillary sinus (Fig. 1a, b). Also noted were scattered foci in the right ethmoid air cells suggestive of tumor extension. The initial biopsy was reported as poorly differentiated carcinoma. Positron emission tomography (PET) confirmed mass extension into the right maxillary antrum sinus, right sphenoid sinus, and right choana-nasopharynx with no involvement of lymph nodes or distant metastatic spread. The patient subsequently underwent an R1 resection including a right medial maxillectomy, ethmoidectomy, sphenoidectomy, dacryocystorhinotomy, right orbital exploration, and right medial canthoplasty for wide resection of the mass and definitive diagnosis. The entire gross visible tumor was removed, and endoscopic evaluation of the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses did not reveal any tumor masses in this area. Due to involvement of the maxillary sinus the patient was staged as T3N0M0.

Fig. 1.

Axial and coronal view T1-weighted enhanced magnetic resonance images showing a large, expansile mass within the right nasal cavity and protruding posteriorly into the right aspect of the choana/nasopharynx, causing leftward deviation of the nasal septum and rightward deviation of the medial wall of the right maxillary sinus (a, b)

The soft tissue mass was removed in pieces and measured 7.8 × 5.5 × 1.6 cm in aggregate. Histology revealed multiple polypoid tissue fragments comprised of highly cellular nests of basaloid tumor cells with scattered eosinophilic ductal formations, and surface lining cells with squamous differentiation (Fig. 2a–d). The mildly pleomorphic basaloid cells with scant cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei formed solid lobular nests separated by fibrous stroma and contained central areas of necrosis (Fig. 2a). The tumor focally exhibited a cribriform growth pattern with lumina containing pale blue material, similar to adenoid cystic carcinoma (Fig. 2a). Scattered anaplastic giant cells were present (Fig. 3a). Hyaline matrix deposition, clear cell change, and brisk mitoses were also noted (Fig. 3b, c). Focal surface squamous dysplasia was identified as well as surface ulceration (Fig. 2d).

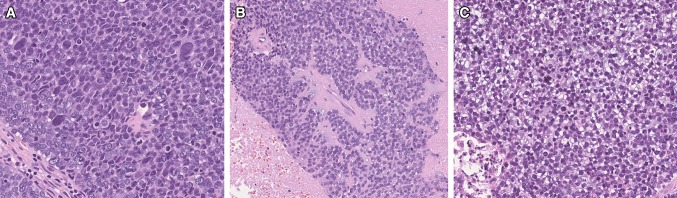

Fig. 2.

A proliferation of basaloid tumor cells in a predominantly solid growth pattern with cribriform areas and microcystic spaces containing mucoid material. Necrosis and frequent mitoses were present (a). Scattered inconspicuous ductal formations (b, c). Squamous dysplasia of the surface epithelium (d)

Fig. 3.

Anaplastic giant cells were present (a). Hyaline matrix deposition and clear cell change were also noted (b, c)

Immunohistochemical studies were performed on 5 µm thick sections prepared from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue using the Ventana’s Benchmark Ultra immunostainer. The following antibodies were utilized: cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (clone AE1 & AE3; Cell Marque Corp., Rocklin, CA); CK7 (clone SP52; Ventana, Tucson, AZ); p16 (clone INK4a; MTM Laboratories, Heidelberg, Germany); EMA (clone E29; Ventana); p63 (clone 4A4; Ventana); CD117 (clone A4502; Santa Clara, CA); S100 (clone 4C4.9; Ventana); SMA (clone 1A4; Cell Marque); INI-1 (clone MRQ-27; Cell Marque); DOG-1 (clone SP31; Cell Marque); desmin (clone DE-R-11; Ventana); synaptophysin (clone SP11; Ventana); chromogranin (clone LK2H10; Ventana); p53 (clone D07; Ventana) and Ki-67 (clone 30-9; Ventana). Immunohistochemistry for ductal and myoepithelial markers revealed a diffuse but biphasic pattern. Staining for CK AE1/AE3 revealed lighter and darker intensity signifying a dual population of cells (Fig. 4a). Additionally, both the solid and ductal components were positive for CK7 (strong and diffuse). Findings also included positivity for p63 (focal patchy), CD117 (focal), S100 (diffuse), smooth muscle actin (focal patchy), epithelial membrane antigen (focal patchy), and INI-1 (diffuse nuclear expression) (Fig. 4b–d). P16 showed strong and diffuse immunoreactivity (> 70% nuclear and cytoplasmic staining) (Fig. 5b). HPV testing was performed using the RNAscope assay. Five micrometer sections from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were evaluated for the presence of HPV RNA using the RNAscope HPV-HR 18 Probe (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA) which recognizes 18 high-risk HPV genotypes (16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, and 82), HPV-LR10 Probe which recognizes 10 low-risk HPV genotypes (6,11, 40, 43, 44, 54, 54, 69, 70, 71, 74), and HPV16/18 Probe for detection of HPV genotypes 16 and 18. RNA in situ hybridization signals for the high-risk HPV cocktail were present, but high-risk HPV subtypes 16/18 were not detected (Fig. 5c). HPV hybridization for low-risk types was negative. Lymphovascular and perineural invasion was not identified. The combination of the morphologic findings, the immunohistochemical and HPV testing results, allowed this nasal tumor to be diagnosed as an HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma. Important immunohistochemical features are shown in Figs. 3, 4. Six weeks after tumor resection, an MRI of the patient’s face was performed and indicated the presence of enhancing material within the remaining right ethmoid air cells anteriorly, right frontal air cells superiorly and medial right extraconal orbit suggestive of postsurgical changes or residual/recurrent tumor. The patient underwent radiotherapy upwards of 70 Gy in 35 fractions over 3 months. He did not receive chemotherapy. Eleven months postoperatively, the patient presented at his routine evaluation with no clinical or radiographic evidence of tumor recurrence.

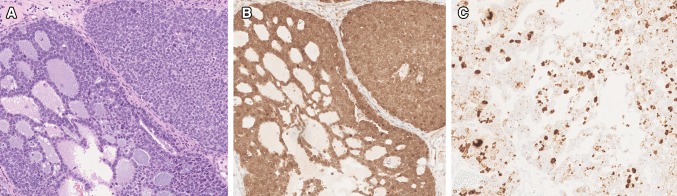

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemistry showing biphasic staining with CKAE1/AE3 (a), focal and patchy p63 expression (b), focal CD117 expression (c), and diffuse, strong staining for S100 (d)

Fig. 5.

HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma with basaloid tumor cells showing diffuse, strong expression for p16 (a, b). RNA in situ hybridization signals for the high-risk HPV cocktail were present in a punctate and diffuse pattern (c)

Discussion

HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma is a rare neoplasm that only recently became included in the World Health Organization classification as a provisional tumor type of the head and neck region [10]. The disease appears to have an increased prevalence in Caucasians and is characterized by a 1.5:1 female to male ratio of disease incidence [2, 8]. The mean age at presentation is 54, with a broad age range from 20 to 90 years old. The tumor only arises in the sinonasal tract and most frequently is either confined to the nasal cavity or involves the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses [8]. Patients typically present with symptoms of nasal obstruction, epistaxis, nasal drainage, pain, and ocular symptoms. Presently, the main treatment strategy is surgical resection with or without radiotherapy or combined chemoradiation therapy. In an expanded series of 49 cases, Bishop et al. established that the presenting tumor stage is variable with 43% of studied patients presenting at a high stage (T3 or T4). The authors also determined that this tumor has a 36% rate of recurrence. Two cases of distant metastases involving the lung and finger were documented, however, no lymph node metastases or tumor related deaths were reported [8, 11]. These findings suggest that although HMSC has a high-grade histologic appearance, it paradoxically exhibits an indolent clinical behavior.

In the majority of cases, and including our own case, this unique sinonasal tumor appears as a hypercellular lesion that grows in nests or sheets of basaloid cells separated by fibrous stroma and has a predominant solid growth pattern. Most cases often exhibit foci of cribriform and/or tubular growth with microcystic spaces containing mucoid material, a pattern that closely resembles ACC [8]. The basaloid cells are characterized by hyperchromatic and angulated nuclei, scant cytoplasm, and an increased nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio with marked increase in mitotic activity [8, 10]. Bishop et al. also notes expanded histologic evidence of myoepithelial differentiation in the form of focal cell spindling, cytoplasmic clearing, plasmacytoid cytomorphology, and extracellular deposition of hyaline matrix-like material [8]. The presence of scattered eosinophilic ductal cells and tubular structures within hypercellular nests of basaloid cells, gives this tumor a biphasic and “salivary-like” appearance.

Squamous dysplasia of the overlying surface epithelium or within the invasive tumor is a unique characteristic that is often observed [8–10, 12], including in our own case, and that allows for distinction from ACC. It appears as atypical giant cells with bizarre, hyperchromatic nuclei and variably prominent nucleoli. It has been suggested that the presence of surface involvement is supportive of the surface epithelium origin of this lesion [8], but currently it is not clear whether this surface squamous atypia is a true premalignant lesion, or secondary tumor extension [13].

More recently in 2017, Bishop et al. reported the identification of additional less consistent histologic features such as: scattered anaplastic giant cells, an inverted growth pattern with fibrovascular cores, squamous differentiation within the invasive tumor, hemangiopericytoma-like vasculature, sarcomatoid transformation including heterologous cartilage formation, and epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma like growth with a prominent clear cell appearance [8, 13].

The newly expanded broad morphological spectrum of HMSC leads to a wide range of differential diagnoses including basaloid squamous carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, high grade myoepithelial carcinoma, SMARCB-1 (INI-1) deficient sinonasal carcinoma, and NUT midline carcinoma [3, 7, 14]. HMSC is considered to be a close mimicker of more commonly occurring salivary gland neoplasms, such as ACC in the sinonasal tract. Given the significant morphologic and immunophenotypic overlap, the distinction between HMSC and ACC may at times be challenging. The main features which help support the diagnosis of HMSC include evidence of high-risk HPV infection by RNA ISH, overlying dysplastic changes in the surface epithelium, and lack of MYB, MYBL1, or NFIB fusion by FISH [1, 7–10]. Other aggressive high-grade salivary gland carcinomas such as basaloid squamous carcinoma and high grade myoepithelial carcinoma also present with a basaloid morphology. Subtle morphologic features are very important for telling all of these tumors apart and immunohistochemistry is critical for narrowing the differential diagnosis. Basaloid squamous carcinoma stains consistently and diffusely for p63 and its more squamous-specific isoform p40, for pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3), and for the high molecular weight cytokeratins such as 5/6 and 34βE12, whereas HMSC lacks diffuse p63/p40 expression and only expresses p63 in its abluminal cells. Other features of HMSC not seen in basaloid SCC include focal ductal differentiation, and expression of myoepithelial markers such as smooth muscle actin, S-100, and calponin [15].

Nut carcinoma is a very poorly differentiated malignancy defined by translocations involving NUT on chromosome 15q14. Morphologically, it grows as nests of tumor cells and shows overt squamous differentiation in the form of keratinization. It is considered one of the so-called “small round blue cell” malignancies with 50% of cases showing positive expression of CD34. In contrast to HMSC, Nut carcinoma is always negative for HPV and its diagnosis requires documenting the presence of a NUT rearrangement [16].

SMARCB1 (INI-1) deficient sinonasal carcinoma is a highly infiltrative malignant neoplasm defined by SMARCB1 inactivation that is also morphologically similar to HMSC. These carcinomas grow as epithelioid nests in the sinonasal submucosa and often display tumor necrosis and a high mitotic rate. Unlike HMSC, however, SMARCB1 (INI-1) deficient sinonasal carcinoma contains rhabdoid cells, does not show squamous or glandular differentiation, and consistently shows negative testing for high risk HPV. It exhibits strong, diffuse cytokeratin expression along with a complete absence of SMARCB1 (INI-1) immunostaining [16].

Immunohistochemistry is critical in narrowing down the differential diagnosis and helpful in distinguishing the dual population of myoepithelial cells. Cytokeratin staining often exhibits a biphasic pattern with darker staining of ductal cells in a background of lighter staining abluminal basaloid cells. Additional immunohistochemical markers of basal/myoepithelial cells that are often expressed in this malignancy include S-100 protein, actin, calponin, and p40 and/or p63. The ductal cells are often positive for CD117 and CK7 [5, 7, 8, 13]. The immunohistochemical results in our case matched the immunoprofile reported for this neoplasm, as the tumor cells showed a biphasic pattern of staining for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3), and both components were also positive for CK7, S-100 protein, p63, epithelial membrane antigen, and focally CD117.

It has been established that 20–25% of sinonasal carcinomas demonstrate high-risk HPV infection [8]. This association is consistently seen in HMSC and is one of its main defining features [7–9]. Most cases of HMSC show the uncommon HPV type 33 as the predominant viral serotype, however, individual cases of infection with HPV 16, 26, 52, and 56 have also recently been reported [4, 8, 17]. Since all cases also show strong and diffuse p16 immunoreactivity in both the basaloid and ductal cell types, a p16 study has been recommended as a routine diagnostic test for sinonasal tract tumors [7, 8, 18]. However, many sinonasal carcinomas are often p16 positive in the absence of HPV, therefore, demonstration of high-risk HPV subtypes either by in situ hybridization or PCR, remains the best way to establish the diagnosis of HMSC [14, 18].

SOX-10 is a transcription factor that is crucial for the differentiation of neural-crest derived cells. Recently, the immunoexpression of this marker has also been reported in a wide range of benign and malignant salivary neoplasms. A study by Hsieh et al. has shown that all basaloid and ductal cells in HMSC are diffusely positive for SOX10, while the overlying atypical squamous epithelium is negative for SOX10. With these findings, the authors suggested that SOX10 may be a useful marker for the differential diagnosis between HMSC and HPV-related SCC of the sinonasal tract [18]. However, a study by Rooper et al. demonstrated frequent diffuse SOX10 positivity in basaloid SCC presenting a significant diagnostic pitfall [19]. SOX10 IHC also cannot differentiate HMSC from ACC since SOX10 is also positive in ACC and other salivary gland tumors staining both ductal and myoepithelial cells [19–21]. ACC is best characterized by fusions involving MYB or MYBL1. The consequent overexpression of MYB protein is commonly used as supporting evidence of ACC [14]. However, a recent study by Shah et al. demonstrated that HMSC has a variable spectrum of staining with the MYB protein, since more than 50% of their cases showed moderate to strong intensity despite consistently lacking MYB rearrangements. Therefore, MYB protein expression should not be utilized as a discriminatory marker for separating HMSC from adenoid cystic carcinoma [14].

Additional data has suggested that B-catenin and lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 (LEF-1) immunoexpression are useful ancillary markers in the diagnosis of salivary tumors. Since these markers show preferential staining in basal cell adenomas/adenocarcinomas, it was originally thought that they may aid in distinguishing HMSC from basal cell adenocarcinoma. However, studies by Shah et al. have demonstrated strong and diffuse nuclear expression of LEF-1 in 10 cases of HMSC, confirming that this marker can lead to a significant pitfall in the distinction of HMSC and basal cell adenocarcinoma [14].

A more complete understanding of this novel entity now makes it slightly less challenging for pathologists to identify this lesion and lowers the chances of a misdiagnosis. Continuous collection of additional cases with a prolonged follow up is necessary for providing insights into the clinical behavior and that may lead to development of the most efficient treatment strategies. The report of this case of HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma is important for further clarification of the biologic behavior and histopathological features of this rare lesion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Katarzyna Brzezinska, Email: kbrzezinska14@gmail.com.

Azzam Hammad, Email: ah3435@drexel.edu.

References

- 1.Hwang S-J, Ok S, Lee H-M, Lee E, Park I-H. Human papillomavirus-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features of the inferior turbinate: a case report. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2015;42(1):53–55. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chouake RJ, Cohen M, Iloreta A. Case report: HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features of the sinonasal tract. Laryngoscope. 2018;128:1515–1517. doi: 10.1002/lary.26957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stelow EB, Bishop JA. Update from the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumours: tumors of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11(1):3–15. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0791-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop JA, Guo TW, Smith DF, et al. Human papillomavirus-related carcinomas of the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:185–192. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182698673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop JA, Ogawa T, Stelow EB, et al. Human papillomavirus-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features: a peculiar variant of head and neck cancer restricted to the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(6):836–844. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31827b1cd6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson LD, Penner C, Ho NJ, et al. Sinonasal tract and nasopharyngeal adenoid cystic carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 86 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:88–109. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0487-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruangritchankul K, Jitpasutham T, Kitkumthorm N, Thorner PS, Keelawat S. Human papillomavirus-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma: first case report associated with an intermediate-risk HPV type and literatures review. Hum Pathol. 2018;14:20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bishop JA, Andreasen S, Hang J-F, et al. HPV-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma: an expanded series of 49 cases of the tumor formerly known as HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic carcinoma-like features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(12):1690–1701. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Udager AM, McHugh JB. Human papilloma-virus associated neoplasms of the head and neck. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10(1):35–55. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Naggar AK, Chen JCK, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah AA, Lamarre ED, Bishop JA. Human papillomavirus-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma: a case report documenting the potential for very late tumor recurrence. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12(4):623–628. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0895-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreasen S, Bishop JA, Hansen TV, et al. Human papillomavirus-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features of the sinonasal tract: clinical and morphological characterization of six new cases. Histopathology. 2017;70:880–888. doi: 10.1111/his.13162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bishop JA, Westra WH. Human papillomavirus-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma: an emerging tumor type with a unique microscopic appearance and a paradoxical clinical behaviour. Oral Oncol. 2018;87:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah AA, Oliai BR, Bishop JA. Consistent LEF-1 and MYB immunohistochemical expression in human papillomavirus-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13(2):220–224. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0951-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis JS. Sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma: a review with emphasis on emerging histologic subtypes and the role of human papillomavirus. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10(1):60–67. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0692-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bishop JA. Newly described tumor entities in sinonasal tract pathology. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10(1):23–31. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0688-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adamane SA, Mittal N, Teni T, et al. Human papillomavirus-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma with unique HPV type 52 association: a case report with review of literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;13(3):331–338. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0969-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh MS, Lee YH, Jin YT, et al. Strong SOX10 expression in human papillomavirus-related multiphenotypic sinonasal carcinoma: report of 6 new cases validated by high-risk human papillomavirus mRNA in situ hybridization test. Hum Pathol. 2018;82:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rooper LM, McCuiston AM, Westra WH, et al. SOX10 immunoexpression in basaloid squamous cell carcinomas: a diagnostic pitfall for ruling out salivary differentiation. Head Neck Pathol. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0990-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miettinen M, McCue PA, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Sox10-a marker for not only schwannian and melanocytic neoplasms but also myoepithelial cell tumors of soft tissue: a systematic analysis of 5134 tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(6):826–835. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh MS, Lee YH, Chang YL. SOX10-positive salivary gland tumors: a growing list, including mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland, sialoblastoma, low-grade salivary duct carcinoma, basal cell adenoma/adenocarcinoma, and a subgroup of mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2016;56:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]