Abstract

Antibiotic resistance is an increasingly important global public health issue, as major opportunistic pathogens are evolving toward multidrug- and pan-drug resistance phenotypes. New antibiotics are thus needed to maintain our ability to treat bacterial infections. According to the WHO, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter, Enterobactericaeae, and Pseudomonas are the most critical targets for the development of new antibacterial drugs. An automated phenotypic screen was implemented to screen 634 synthetic compounds obtained in-house for both their direct-acting and synergistic activity. Fourteen percent and 10% of the compounds showed growth inhibition against tested Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, respectively. The most active direct-acting compounds showed a broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, including on some multidrug-resistant clinical isolates. In addition, 47 compounds were identified for their ability to potentiate the activity of other antibiotics. Compounds of three different scaffolds (2-quinolones, phenols, and pyrazoles) showed a strong potentiation of colistin, some being able to revert colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii.

Keywords: Antibacterials, Unfocused screening, ESKAPE bacteria, Antibiotic potentiation, Acinetobacter baumannii

Antibiotic resistance has reached alarming levels globally, with the World Health Organization describing this Public Health issue as a “formidable threat to global health and sustainable development” and surely one of the most relevant medical and socio-economic challenges of the XXI century.1 Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) still account for a large number of difficult-to-treat hospital acquired infections.2,3 Furthermore, Gram-negative opportunistic pathogens are more commonly exhibiting extensively drug- or pandrug-resistance phenotypes, which significantly limit treatment options for the infections caused by such organisms, especially in immunocompromised, pediatric, or elder patients in the nosocomial setting.4,5 Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacteriaceae are considered the most urgent threat to address, and novel antibiotics active against antibiotic-resistant isolates are extremely desirable.6,7

The discovery of new antibacterial compounds is thus of primary importance. Many strategies have been elaborated to identify and develop compounds of potential clinical usefulness. These include the identification of novel compounds belonging to a well-known and validated class of antibacterial drugs (or close analogues) that would show activity on antibiotic-resistant clinical isolates, by eluding the resistance mechanism produced by the bacterium. Examples of such a strategy are represented by the development of second-generation oxazolidinones, active on linezolid-resistant strains with mutations in the 50S rRNA gene, or by the fifth-generation cephalosporins ceftaroline and ceftobiprole that efficiently bind to the S. aureus PBP2x, refractory to inhibition by other β-lactams and produced by methicillin-resistant isolates (MRSA).8 Eravacycline, a synthetic tetracycline that recently received FDA approval, shows potent activity on a wide range of antibiotic-resistant organisms, including Acinetobacter baumannii.9 New β-lactam inhibitor/β-lactam combinations were also recently introduced in the clinical practice (avibactam/ceftazidime, vaborbactam/Meropenem)6 or are in the late stage of clinical development (taniborbactam/cefepime).10,11 Other innovative β-lactamase inhibitors, which revert carbapenemase production in relevant opportunistic pathogens (ANT2681, QPX7728), are also being described.12,13 Fluoroquinolones represent another class of successful antibacterial drugs, originally mostly active on Gram-negative bacteria, but later generations of drugs show a broad spectrum of activity, encompassing Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, as well as Mycobacterium tuberculosis.14

In this work, we screened an unfocused library of 634 synthetic compounds for their antibacterial activity, which allowed us to identify and characterize novel molecules with a strong direct or synergistic activity on key clinically relevant bacteria, including ESKAPE antibiotic-resistant clinical isolates.15

The library included several series of unrelated compounds, all synthesized in-house and representing at least six different chemical scaffolds and/or structures. The solubility of the compounds in DMSO was variable, although 48% of them were soluble at a concentration of 50 mg/mL. The other compounds were soluble at lower concentrations (25, 12.5, or 6.25 mg/mL), and only 14% were insoluble at 6.25 mg/mL. All 634 compounds were nonetheless tested, although for the latter group, the suspension was extensively vortexed immediately prior to testing. The protocol implemented on a liquid-handling automated platform able to maintain sterility conditions, and based on a simple agar diffusion method, was validated to easily and rapidly screen compounds endowed with antibacterial activity and allowed the identification of active compounds with an excellent reproducibility.

A total of 343 molecules (54%) were found to inhibit the growth of at least one tested organism, by showing a growth inhibition zone diameter of at least 4 mm. This criterion was intentionally low in order to allow the identification of compounds with moderate activity but whose structure could potentially represent a starting point for further optimization (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative distribution of active molecules according to their spectrum of activity.

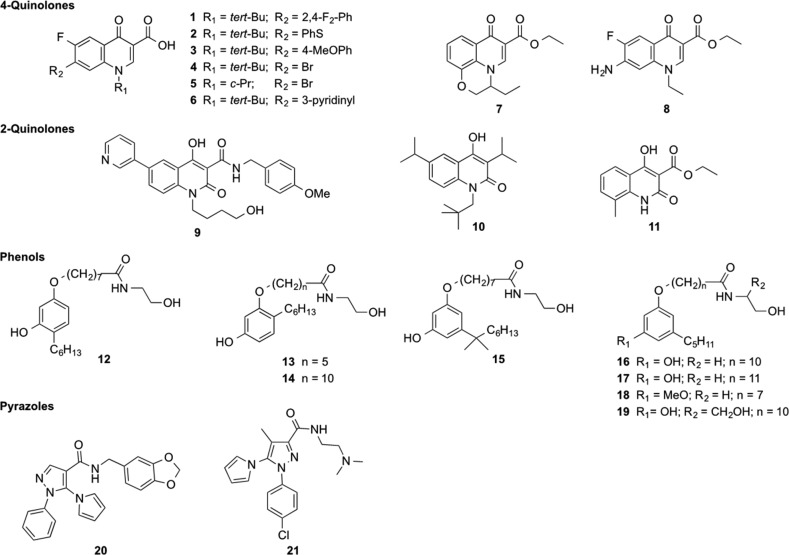

Unsurprisingly, the largest number of compounds was found to inhibit the growth of Gram-positive bacteria, especially Bacillus subtilis. Ninety-two compounds showed activity against all four Gram-positive type strain organisms. However, our screening campaign also showed a relatively good hit rate against Gram-negative bacteria, with 182 compounds inhibiting the growth of at least one organism, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii being the most frequently inhibited organisms. Among these, a total of 67 compounds inhibited the growth of all four tested Gram-negative bacteria. A smaller number of compounds (N = 8) were able to inhibit the growth of all eight tested organisms, thus including both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The average diameter of growth inhibition, together with the antibacterial spectrum, were used as criteria to rank the various molecules and allowed the identification of 9 potent (diameter of growth inhibition, ≥10 mm) molecules with a broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. These compounds (1–9, Chart 1) were particularly active on organisms of high clinical relevance (K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, staphylococci, and enterococci). Compound 9, a 4-hydroxy-2-quinolone, showed broad-spectrum activity on all Gram-positive bacteria, while having limited activity on Gram-negatives, especially E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Compound 8, a substituted 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid ethyl ester, exhibited activity on K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii.

Chart 1. Structure of Compounds 1–21 and Scaffolds They Represent.

The antibacterial activity of these compounds was further investigated by measuring their MIC (minimal inhibitory concentration) values on a panel of organisms, including recent clinical isolates showing different phenotypes of resistance to antibiotics (Table 1, Table SI1).

Table 1. Antibacterial Activity of Selected Compounds 1–9 Showing Significant Growth Inhibition in the Agar Diffusion Assay.

| MIC

(μg/mL) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strain | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Type Strains | |||||||||

| E. coli CCUGT | 16 | 16 | >256 | 8 | 0.25 | 2 | >256 | 32 | 64 |

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 13833 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 1 | ≤0.12 | 0.25 | 128 | 128 | 32 |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | 64 | 256 | >256 | 32 | 8 | 4 | >256 | >256 | 256 |

| A. baumannii ATCC 17978 | 8 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 256 | 256 | 16 |

| B. subtilis ATCC 6633 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | 128 | 32 | 0.12 |

| E. faecalis ATCC 29212 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 4 | 0.5 | 256 | 256 | 16 |

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 2 | 2 | 0.25 | 8 | 4 | ≤0.12 | >256 | 256 | 4 |

| S. pyogenes ATCC 12344 | 1 | 1 | ≤0.12 | 8 | 4 | ≤0.12 | >256 | 64 | 8 |

| Clinical Isolates | |||||||||

| E. cloacae VA-417/02 | 4 | 16 | 128 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | >256 | >256 | 64 |

| E. cloacae Z19 | >256 | 256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | 256 | >256 | >256 | >256 |

| E. coli Z25 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | 256 | >256 | >256 | >256 |

| P. aeruginosa VR-143/97 | >256 | 128 | >256 | >256 | 256 | 64 | >256 | >256 | >256 |

| A. baumannii AC-54/97 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | 256 | 64 | >256 | >256 | >256 |

Overall, these compounds were more active on Gram-positive organisms than on Gram-negatives. Among the latter, they were also commonly more active on E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and A. baumannii (MIC values as low as ≤0.12 μg/mL) rather than on P. aeruginosa, for which MIC values were consistently ≥4 μg/mL. Strikingly, compounds 7 and 8, despite showing a good activity in agar-based diffusion assay, only showed a limited activity (MIC values, ≥32 μg/mL), indicating that the presence of a carboxyester group is largely detrimental for the antibacterial activity. Unfortunately, the lack of activity of these compounds against Gram-negative clinical isolates resistant to fluoroquinolones, including strains producing a Qnr ribosomal protection factor (E. cloacae Z19 and E. coli Z25) (Table 1), represents an important limitation. However, these compounds remain interesting regarding their peculiar antibacterial spectrum, and further studies will evaluate their activity on quinolone-resistant Gram-positive strains. Furthermore, these compounds also showed a very good selectivity toward bacterial cells, as they did not show any cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells at concentrations of up 250 μg/mL (LDH release <20%).

In addition to the identification of direct-acting agents, our screening campaign included agar diffusion-based assays in which the potential synergistic activity of a compound could be detected. This approach is more and more common and allowed the identification of many interesting new classes of so-called “antibiotic potentiators”.16 A successful example of this approach is illustrated by SPR-741, a polymyxin B1 analog currently in clinical development.17,18 We used this approach with the intent to detect molecules that would show a limited direct activity on Gram-negative primarily because they would be substrates of efflux systems or membrane transporters, or because they would not show a sufficient permeation rate through the outer membrane. For that reason, we used benzylpenicillin and vancomycin for which the target is present in Gram-negative bacteria but do not show intrinsic activity because of these mechanisms (benzylpenicillin is pumped out of the periplasm while vancomycin could not cross the outer membrane). We also tested the synergistic activity in the presence of aztreonam (a β-lactam stable to many β-lactamases, including metallo-carbapenemases) and colistin, a polymyxin well-known for its membrane permeabilization properties.19 All 634 compounds were then tested using Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 as an indicator strain, in the absence and presence of subinhibitory concentration (see Experimental Procedures) of antibiotic in the culture medium. Forty-seven compounds showed a significant difference between the diameter of the growth inhibition zone in the presence and absence of antibiotic (≥4 mm). Interestingly, all but one (compound 9) of these compounds were different from those previously identified and showing a direct activity. Thirty-nine compounds showed growth inhibition of Acinetobacter baumannii when tested in the presence of colistin, which was the most effective potentiator, likely due to its membrane permeabilization effect and possibly granting access to an unidentified molecular target located in the periplasm or cytoplasm. Twelve and eight compounds showed growth inhibition when tested in the presence of benzylpenicillin or aztreonam, respectively, while only two were active in the presence of vancomycin. Considering the high sensitivity of agar-based diffusion assay in our setup, the synergistic activity was then further investigated in broth microdilution assays (Figure 2) and confirmed a significant reduction of the MIC (≥3 fold) for only 13 compounds, primarily in the presence of colistin.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the synergistic activity using broth microdilution (MIC values measured in the absence and presence of a fixed subinhibitory concentration of a commercially available antibiotic) of compounds showing enhanced growth inhibition in agar diffusion assay in the presence of an antibiotic, reporting the potentiation fold. The number of tested molecules for each condition is reported in the graph legend.

Interestingly, the chemical structure of these active compounds belong to different scaffolds. The most active compounds 9–21, showing a potentiation fold of 3 log2 to 8 log2 dilutions (8- to 256-fold reduction of the MIC), represent three distinct chemical series, namely, 2-quinolone derivatives, substituted phenols, and pyrazoles (Chart 1). Even more interestingly, this synergistic activity of these compounds was confirmed on other Gram-negative species of high clinical relevance, i.e., Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli and, for substituted phenols, on Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Table 2).

Table 2. Synergistic Activity of Selected Compounds with Colistin (at a Fixed Concentration Equivalent to 0.5 × MIC) on Gram-Negative Bacteria of High Clinical Relevance.

| MIC,a μg/mL (potentiation fold, log2) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | A. baumannii ATCC 17978 | E. coli CCUGT | K. pneumoniae ATCC 13833 | P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 |

| 2-Quinolones | ||||

| 9 | 16 (5) | 32 (4) | 64 (3) | –b |

| 10 | 32 (4) | 32 (4) | 64 (3) | – |

| 11 | 64 (3) | 64 (3) | 16 (5) | – |

| Phenols | ||||

| 12 | 16 (5) | 8 (6) | 4 (7) | – |

| 13 | 8 (6) | – | – | – |

| 14 | 16 (5) | 4 (7) | 8 (6) | – |

| 15 | 4 (7) | 2 (8) | 4 (7) | – |

| 16 | 2 (8) | 8 (6) | 4 (7) | 2 (8) |

| 17 | 4 (7) | 8 (6) | 8 (6) | 4 (7) |

| 18 | 4 (7) | 4 (7) | 8 (6) | – |

| 19 | 4 (7) | 8 (6) | 8 (6) | – |

| Pyrazoles | ||||

| 20 | 32 (4) | 64 (3) | 64 (3) | – |

| 21 | 16 (5) | 64 (3) | 32 (4) | – |

To further confirm true synergism, rather than a purely additive effect, checkerboard analyses were carried out with selected compounds representative of the three scaffolds (9, 16, 17, 20). The determination of the average FIC (fractional inhibitory concentration) index, a parameter that should be <0.5 in the case of a synergistic interaction between two active molecules,20 revealed that only phenols and pyrazoles exhibited a synergistic activity with colistin (tested on Acinetobacter baumannii; average FIC indexes were 0.29, 0.31, and 0.38 for 16, 17, and 20, respectively), while the tested 2-quinolone derivative 9 did not (average FIC index, 0.56) when tested on Escherichia coli. The synergistic activity of phenol derivatives 16 and 17 with colistin was also confirmed on P. aeruginosa (average FIC index, 0.41 with both compounds).

On the basis of these results, compounds 16, 17, 18, and 20 were selected for further analysis, including their ability to revert colistin resistance on clinical isolates showing multidrug or near pan-drug resistance phenotypes. This was assessed to measuring the MIC of the compound in the presence of colistin at a concentration of 2 μg/mL, corresponding to the current EUCAST clinical breakpoint for both Enterobacterales and Acinetobacter baumannii.21 Unfortunately, none of the compounds was able to inhibit the growth (MIC, >64 μg/mL) of colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae clinical isolates (colistin MIC, 64 and 256 μg/mL), except, to some extent, compound 18 (Table 3). However, they showed a much better activity on Acinetobacter baumannii, an OXA-24-producing colistin-resistant clinical isolate,22 as compound 16 could restore colistin susceptibility at concentrations as low as 2 μg/mL, showing an excellent synergism (average FIC index, 0.062).

Table 3. Synergistic Activity with Colistin on Resistant Clinical Isolates and Cytotoxicity of Selected Pyrazole and Phenol (or Methoxy Analogue Thereof) Derivatives.

| MIC

(μg/mL) to restore inhibition in the presence of 2 μg/mL

COL |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | K. pneumoniae SI-004Bo | K. pneumoniae SI-081R | A. baumannii N50 | IC50 (HeLa cells) |

| 16 | >64 | >64 | 2 | 25 |

| 17 | >64 | >64 | 4 | 18 |

| 18 | >64 | 16 | 8 | >60 |

| 20 | >64 | >64 | 32 | >60 |

Finally, a preliminary assessment of compound selectivity was performed using a membrane integrity assay on HeLa cells. Substituted phenols 16 and 17 exhibited IC50 values of 25 and 18 μg/mL, respectively (Table 3). Interestingly, compound 18, a methoxy analogue with a shorter aliphatic chain, appeared less toxic (IC50 >60 μg/mL), similarly to the substituted pyrazole 20. Although this therapeutic window is not sufficient to warrant any therapeutic application at this stage, especially considering the lower activity of compound 20, these two scaffolds could represent a novel starting point for the optimization, although potentially challenging, of more active compounds acting as colistin resistance breakers active on MDR Acinetobacter baumannii isolates.

As to the preparation of these compounds, the carboxylic acids 1–6 had been previously synthesized and tested as antitubercular agents,23 while 7 and 8 had been used as synthetic intermediates for the preparation of other compounds already published.24,25 Compound 9 is a new compound recently synthesized (Scheme 1), according to the procedure described for similar compounds, to be included in the screening campaign. Suzuki–Miyaura coupling of 1-(4-acetoxy-1-butyl)-6-bromo-4-hydroxy-N-(4-methoxybenzyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide (22)26 with 3-pyridineboronic acid under microwave irradiation in a basic medium furnished directly compound 9, due to concurrent hydrolysis of the acetate function.

Scheme 1. Palladium-Catalyzed Synthesis of Compound 9.

Reagents and reaction conditions: (a) 3-pyridineboronic acid, Pd(OAc)2, PPh3, 1 M Na2CO3, EtOH, 1,2-dimethoxyethane, microwaves, 150 °C, 5 min, 50%.

Most of the phenol derivatives tested had previously raised our interest for their ability to modulate cannabinoid receptors and/or TRPA channels. Surprisingly enough, 16 and 17 have emerged from our screening as the most active derivatives, with 15, 19, and 18 immediately behind in the ranking. Although we have already reported on the syntheses of 16,2717,2815,29 and 19,30 the preparation of 18 has been carried out recently starting from methyl 8-(3-hydroxy-5-pentylphenoxy)octanoate (23),30 as highlighted in Scheme 2. After methylation of the phenolic OH with methyl iodide, the ester derivative was hydrolyzed with sodium hydroxide to give the corresponding acid, which without purification was subjected to amidation reaction with ethanolamine in the presence of HBTU/HOBt to provide 18.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Compound 18.

Reagents and reaction conditions: (a) (i) NaH, CH3I, dry THF, 0 °C to rt, 95%; (ii) MeOH/aqueous NaOH (3.0 equiv), reflux, 3 h; (iii) ethanolamine, HOBt, EDC, DCM, rt, 76% overall.

Compounds 20 and 21 represent a further elaboration of known carboxylic acids into amides with different physicochemical properties, in particular an amide with a basic nitrogen that is protonated at physiological pH (21) and a more lipophilic amide (20). Thus, 1-phenyl-5-(1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylic acid (24)31 and 1-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-methyl-5-(1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid (25)32 were reacted with N,N,N′-trimethylethylenediammine and piperonylamine, respectively, in the presence of EDC/HOBt to give the expected amides 20 and 21 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Compounds 20 and 21.

Reagents and reaction conditions: (a) appropriate amine, EDC, HOBt, DCM, rt, 47% (20), 67% (21).

In conclusion, our approach allowed us to identify compounds with both direct and synergistic activity, some with rather low in vitro toxicity on HeLa cells. Overall, this screening campaign showed a rather high hit rate toward clinically relevant Gram-negative species. Compounds showing direct antibacterial activity were 2- and 4-quinolones. The latter, despite primarily synthesized as analogues of vosaroxin, an antitumor drug for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia,33 showed a very potent direct antibacterial activity with very good selectivity. To our best knowledge, there is relatively little knowledge regarding the antibacterial activity of 2-quinolones, which we found to have modest direct but significant potentiation of colistin on key opportunistic pathogens such as Enterobacterales or A. baumannii. Furthermore, we identified two new classes (substituted phenols and pyrazoles) of molecules with synergistic activity with colistin on several Gram-negatives, including K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, or A. baumannii. These could serve as a basis for the optimization of colistin resistance breakers to be used in combination for the treatment of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii infections but would also potentially allow for a lower dosage of drugs of the polymyxin class, often used as a last resort, despite its frequent adverse effects due to its suboptimal safety. Additional studies are needed to further understand the molecular basis of the synergistic activity of these compounds with colistin and whether it would rely on the permeabilizing properties of colistin or on the membrane-targeting activity (or membrane-bound proteins) of our compounds.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide

- FIC

fractional inhibitory concentration

- HOBt

hydroxybenzotriazole

- MIC

minimal inhibitory concentration

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00674.

Author Contributions

# These authors contributed equally to this work.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Authors acknowledge the partial support by MIUR Progetto Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2018–2022, grant L. 232/2016.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Dedication

This article is dedicated to the memory of Professor Maurizio Botta, committed teacher, enthusiastic researcher, respected colleague, and much-loved friend.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ledingham K.; Hinchliffe S.; Jackson M.; Thomas F.; Tomson G.. Antibiotic Resistance: Using a Cultural Contexts of Health Approach to Address a Global Health Challenge; World Health Organization, 2019.

- Lakhundi S.; Zhang K. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Molecular Characterization, Evolution, and Epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31 (4), e00020-18. 10.1128/CMR.00020-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. R.; Murray B. E.; Rice L. B.; Arias C. A. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci: Therapeutic Challenges in the 21st Century. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2016, 30 (2), 415–439. 10.1016/j.idc.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossolini G. M.; Arena F.; Pecile P.; Pollini S. Update on the Antibiotic Resistance Crisis. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2014, 18, 56–60. 10.1016/j.coph.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassini A.; Högberg L. D.; Plachouras D.; Quattrocchi A.; Hoxha A.; Simonsen G. S.; Colomb-Cotinat M.; Kretzschmar M. E.; Devleesschauwer B.; Cecchini M.; et al. Attributable Deaths and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years Caused by Infections with Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: A Population-Level Modelling Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19 (1), 56–66. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30605-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docquier J.-D.; Mangani S. An Update on β-Lactamase Inhibitor Discovery and Development. Drug Resist. Updates 2018, 36, 13–29. 10.1016/j.drup.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacconelli E.; Magrini N.. Global Priority List of Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics; World Health Organization,https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/WHO-PPL-Short_Summary_25Feb-ET_NM_WHO.pdf, accessed December 18, 2019.

- David M. Z.; Dryden M.; Gottlieb T.; Tattevin P.; Gould I. M. Recently Approved Antibacterials for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Other Gram-Positive Pathogens: The Shock of the New. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 50 (3), 303–307. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. R.; Burton C. E. Eravacycline, a Newly Approved Fluorocycline. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38 (10), 1787–1794. 10.1007/s10096-019-03590-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Trout R. E. L.; Chu G.-H.; McGarry D.; Jackson R. W.; Hamrick J.; Daigle D.; Cusick S.; Pozzi C.; De Luca F. Discovery of Taniborbactam (VNRX-5133): A Broad-Spectrum Serine- and Metallo-β-Lactamase Inhibitor for Carbapenem-Resistant Bacterial Infections. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick J. C.; Docquier J.-D.; Uehara T.; Myers C. L.; Six D. A.; Chatwin C. L.; John K. J.; Vernacchio S. F.; Cusick S. M.; Trout R. E. L. VNRX-5133 (Taniborbactam), a Broad-Spectrum Inhibitor of Serine- and Metallo-β-Lactamases, Restores Activity of Cefepime in Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 10.1128/AAC.01963-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanheira M.; Lindley J.; Huynh H.; Mendes R. E.; Lomovskaya O. 677. Activity of Novel β-Lactamase Inhibitor QPX7728 Combined with β-Lactam Agents When Tested Against Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) Isolates. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6 (Suppl 2), S309. 10.1093/ofid/ofz360.745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoccia F.Interaction of the Metallo β-Lactamase Inhibitor ANT2681 with NDM-Type Enzymes Shows a pH Dependent Potency and in vitro Antibacterial Activity. ASM Microbe 2019, San Francisco, June 20–24, 2019; Abstract 2019-LB-6853; ASM Press: Washington, DC, 2019.

- Thee S.; Garcia-Prats A. J.; Donald P. R.; Hesseling A. C.; Schaaf H. S. Fluoroquinolones for the Treatment of Tuberculosis in Children. Tuberculosis (Oxford, U. K.) 2015, 95 (3), 229–245. 10.1016/j.tube.2015.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher H. W.; Talbot G. H.; Bradley J. S.; Edwards J. E.; Gilbert D.; Rice L. B.; Scheld M.; Spellberg B.; Bartlett J. Bad Bugs, No Drugs: No ESKAPE! An Update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48 (1), 1–12. 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright G. D. Antibiotic Adjuvants: Rescuing Antibiotics from Resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24 (11), 862–871. 10.1016/j.tim.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett D.; Wise A.; Langley T.; Skinner K.; Trimby E.; Birchall S.; Dorali A.; Sandiford S.; Williams J.; Warn P. Potentiation of Antibiotic Activity by a Novel Cationic Peptide: Potency and Spectrum of Activity of SPR741. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61 (8), e00200-17. 10.1128/AAC.00200-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckburg P. B.; Lister T.; Walpole S.; Keutzer T.; Utley L.; Tomayko J.; Kopp E.; Farinola N.; Coleman S. Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Drug Interaction Potential of SPR741, an Intravenous Potentiator, after Single and Multiple Ascending Doses and When Combined with β-Lactam Antibiotics in Healthy Subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63 (9), 00892-19. 10.1128/AAC.00892-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui P.; Niu H.; Shi W.; Zhang S.; Zhang H.; Margolick J.; Zhang W.; Zhang Y. Disruption of Membrane by Colistin Kills Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Persisters and Enhances Killing of Other Antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60 (11), 6867–6871. 10.1128/AAC.01481-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. J.; Middleton R. F.; Westmacott D. The Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) Index as a Measure of Synergy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1983, 11 (5), 427–433. 10.1093/jac/11.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST: Clinical breakpoints and dosing of antibiotics, http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/ (accessed Dec 31, 2019).

- D’Andrea M. M.; Giani T.; D’Arezzo S.; Capone A.; Petrosillo N.; Visca P.; Luzzaro F.; Rossolini G. M. Characterization of PABVA01, a Plasmid Encoding the OXA-24 Carbapenemase from Italian Isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53 (8), 3528–3533. 10.1128/AAC.00178-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini V.; De Rosa M.; Pasquini S.; Mugnaini C.; Brizzi A.; Cuppone A. M.; Pozzi G.; Corelli F. New fluoroquinolones active against fluoroquinolones-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. Tuberculosis 2013, 93, 405–411. 10.1016/j.tube.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquini S.; De Rosa M.; Pedani V.; Mugnaini C.; Guida F.; Luongo L.; De Chiaro M.; Maione S.; Dragoni S.; Frosini M.; Ligresti A.; Di Marzo V.; Corelli F. – Investigations on the 4-Quinolone-3-carboxylic Acid Motif. 4. Identification of New Potent and Selective Ligands for the Cannabinoid Type 2 Receptor with Diverse Substitution Patterns and Anti-Hyperalgesic Effects in Mice. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 5444–5453. 10.1021/jm200476p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artico M.; Corelli F.; Massa S.; Stefancich G.; Panico S.; Simonetti N. Studies on antibacterial and antifungal agents. Note VI. Pirfloxacin and related compounds: synthetic and microbiological studies. Farmaco, Ed. Sci. 1986, 4, 366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnaini C.; Brizzi A.; Ligresti A.; Allarà M.; Lamponi S.; Vacondio F.; Silva C.; Mor M.; Di Marzo V.; Corelli F. Investigations on the 4-Quinolone-3-carboxylic Acid Motif. 7. Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of 4-Quinolone-3-carboxamides and 4-Hydroxy-2-quinolone-3-carboxamides as High Affinity Cannabinoid Receptor 2 (CB2R) Ligands with Improved Aqueous Solubility. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 1052–1067. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizzi A.; Brizzi V.; Cascio M. G.; Bisogno T.; Sirianni R.; Di Marzo V. Design, Synthesis, and Binding Studies of New Potent Ligands of Cannabinoid Receptors. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 7343–7350. 10.1021/jm0501533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizzi A.; Cascio M. G.; Brizzi V.; Bisogno T.; Dinatolo M. T.; Martinelli A.; Tuccinardi T.; Di Marzo V. Design, synthesis, binding, and molecular modeling studies of new potent ligands of cannabinoid receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 5406–5416. 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizzi A.; Brizzi V.; Cascio M. G.; Corelli F.; Guida F.; Ligresti A.; Maione S.; Martinelli A.; Pasquini S.; Tuccinardi T.; Di Marzo V. New Resorcinol-Anandamide “Hybrids” as Potent Cannabinoid Receptor Ligands Endowed with Antinociceptive Activity in Vivo. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 2506–2514. 10.1021/jm8016255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizzi A.; Aiello F.; Marini P.; Cascio M. G.; Corelli F.; Brizzi V.; De Petrocellis L.; Ligresti A.; Luongo L.; Lamponi S.; Maione S.; Pertwee R. G.; Di Marzo V. Structure-affinity relationships and pharmacological characterization of new alkyl-resorcinol cannabinoid receptor ligands: identification of a dual cannabinoid receptor/TRPA1 channel agonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 4770–4783. 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa S.; Mai A.; Artico M.; Corelli F. Heterocyclic system. XI. Synthesis of 1H,4H-pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyrrolizine and 2H,4H-pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyrrolizine derivatives. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1990, 27, 1805–1808. 10.1002/jhet.5570270653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri R.; Cascio M. G.; La Regina G.; Piscitelli F.; Lavecchia A.; Brizzi A.; Pasquini S.; Botta M.; Novellino E.; Di Marzo V.; Corelli F. Synthesis, Cannabinoid Receptor Affinity, and Molecular Modeling Studies of Substituted 1-Aryl-5-(1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamides. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 1560–1576. 10.1021/jm070566z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotinski A. K.; Lewis I. D.; Ross D. M. Vosaroxin Is a Novel Topoisomerase-II Inhibitor with Efficacy in Relapsed and Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2015, 16 (9), 1395–1402. 10.1517/14656566.2015.1044437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.