Abstract

In this work, three samples of fluoroelastomers/glycidyl azide polymer/hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane (F2602/GAP/CL-20) energetic fibers with F2602/GAP:CL-20 ratios of 1:9, 2:8, and 3:7 were prepared by the electrospinning method. The morphologies and structures of the samples were characterized by scanning electron microscopy, energy dispersive spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. The results revealed that F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fibers showed a three-dimensional network structure, and four elements C, N, O, and F were observed on the surface. The surface of the fiber F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9 was uniform and smooth. Differential scanning calorimetry was used to analyze the thermal decomposition properties of the samples. The apparent activation energy of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber was 399.86 kJ/mol, indicating high thermal stability. TG-MS analysis results show that the thermal decomposition products of F2602/GAP/CL-20 are mainly C2H6, H2O, N2, and CO2. The results of the energy performance evaluation showed that the standard specific impulse (Isp) of F2602/GAP/CL-20 was 2668.1 N s kg–1, which was remarkably higher than Isp of the state-of-the-art AP/HTPB/Al propellant. In addition, compared to that of CL-20, the friction sensitivity of one F2602/GAP/CL-20 sample decreased by 38%, and the sensitivities of the other two F2602/GAP/CL-20 samples were even less than zero. F2602/GAP/CL-20 fibers also exhibited a higher feature height. Therefore, these kinds of CL-20-based fibers are high-energy materials with very low sensitivity.

1. Introduction

Hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane (CL-20) is a new energetic material with high energy and density, synthesized by Dr. Nielsen of the United States.1 ε-CL-20 is used as a rocket propellant and high-energy explosive because of its excellent energy performance.2 Its crystal density can reach 2.04 g·cm–3, the theoretical explosion pressure is 43GPa, the theoretical explosion speed can reach more than 9500 m/s, and the energy output can be 10–15% higher than that of HMX. However, CL-20 has limited applications due to its higher sensitivity. Hence, a large number of studies have been conducted on reducing the sensitivity of CL-20 at home and abroad. Chenxi Qu et al. summarized the research progress of CL-20 crystal modification technology to reduce sensitivity at home and abroad, compared and summarized the co-crystallization and core–shell structure coating, the two methods of sensitivity reduction, and analyzed its mechanism.3 They also proposed the use of energetic binders or other insensitive energetic materials as shell materials for surface modification, so as to solve the issue that CL-20 coated with nonenergetic substances may reduce the explosive power of coating products and polymer self-agglomeration.

The glycidyl azide polymer (GAP) is a high-nitrogen-containing energetic adhesive with high energy, high density, and low glass transition temperature and is often used as a rocket propellant, pyrotechnic agent, and plastic-bonded explosive (PBX).4 Baoyun Ye et al. used GAP and stabilizing nitrocellulose (NC) as composite cladding agents to coat the surface of CL-20 using the water suspension method, and the characteristic drop height increased from 17.3 and 29.46 cm before coating to 36.74 cm, effectively reducing its mechanical sensitivity.5 Shaohua Jin et al. used fluoro rubber to coat CL-20 by the extrusion granulation method and the solution/water suspension method and found that the coating effects obtained by different coating methods were quite different.6 The results showed that these kinds of coating processes were relatively complicated, the samples prepared were relatively loose, and the effect of reducing sensitivity needs to be improved.

Electrospinning is one of the main methods for preparing nanofiber materials because of its simple operation, low spinning cost, and controllable process. The fibers prepared by the electrospinning method generally have a diameter ranging from a few nanometers to a few micrometers, which not only have the advantages of small size and high specific surface area, but also have the characteristics of good mechanical stability, small pore diameter, high porosity, and good fiber continuity.7 For example, using an electrostatic spinning device, Yan et al.8 prepared CL-20 microspheres, Luo et al.9 prepared NC/GAP/nano-LLM-105 nanofibers, Yao et al.10 prepared RDX/F2604 composites, Tianhong Zhou et al.11 prepared F2604/AP composites, and Zhang et al.12 investigated the effect of spinning parameters on the preparation of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF). Fluoroelastomers have the characteristics of heat resistance, oil resistance, high-temperature resistance, and good chemical stability,13 which make it an indispensable material for application in modern aviation, missiles, and rockets. Among them, type 26 fluoroelastomer is one of the most widely used fluoroelastomers, and it is also commonly used as an adhesive for explosives. Hou et al.,14 Bian Bian et al.,15 and Ji et al.16 successfully coated F2602 on the surface of HMX by the one-step granulation method and used the suspension spray-drying method to prepare HMX/F2602 microspheres, which reduced the sensitivity of HMX and improved the safety performance of HMX. In this study, F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fibers were prepared by electrostatic spinning with F2602/GAP as the coating binder and CL-20 as the high-energy explosive.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Morphology and Structure

It can be seen from Figure 1(a-c) that three different proportions of F2602/GAP/CL-20 fibers all show a three-dimensional network structure with a branching phenomenon and a disordered arrangement among the fibers. This is because the fibers arriving later in the receiving device have the same charge polarity as the fibers arriving first, so they are arranged at a larger angle with the fibers in the earlier stage. The surface of the fiber F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9 is uniform and smooth. As shown in the particle size distribution chart (Figure 1d,e), its average diameter is 385 nm and the median diameter d50 of the volume curve obtained by integrating the frequency curve is 377 nm. A large number of fibers with F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 2:8, different thicknesses, and fineness are broken, and there is explosive agglomeration. The fiber F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 2:8 has a mean diameter of 426 nm and a median diameter d50 of 430 nm. The fiber morphology is better when F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 3:7, the average fiber diameter is 481 nm and the median fiber diameter d50 is 472 nm, and lots of holes are formed. When these three samples are observed, it can be seen that the diameter of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 fibers increases with the proportion of F2602/GAP in the energetic fiber. This is because the increase of the binder content causes the degree of entanglement of the molecular chains in the solution to increase, and the orientation of the molecular chains in the electrospinning process requires a larger electric field force, so the diameter of the prepared fiber will also be larger.

Figure 1.

(a-c) SEM images of F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9, F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 2:8, and F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 3:7; (d, e) diameter distribution of F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9; (f, g) diameter distribution of F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 2:8; (h, i) diameter distribution of F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 3:7.

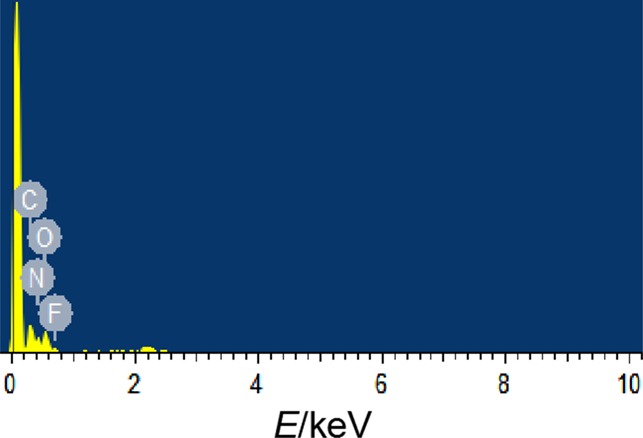

EDS analysis was performed on the surface elements of F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fibers, as shown in Figure 2. In the figure, the surface of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber contains four elements C, N, O, and F, which are consistent with the elements of F2602, GAP, and CL-20. As shown in Table 1 of theoretical elemental contents in the EDS spectrum, with the increase of the F element content, the content of the C element increases, and the contents of N and O elements decrease, indicating that F2602/GAP is attached to the surface of CL-20.

Figure 2.

EDS spectrum of F2602/GAP/CL-20.

Table 1. Theoretical Elemental Contents from EDS Analysis.

| sample | C content (%) | N content (%) | O content (%) | F content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9 | 28.69 | 32.66 | 33.57 | 5.07 |

| F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 2:8 | 28.69 | 31.43 | 32.87 | 7.02 |

| F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 3:7 | 32.50 | 28.91 | 29.02 | 9.58 |

Figure 3a shows the IR spectra of the samples. In the spectra, F2602/GAP shows a strong absorption peak of −N3 from GAP at 2094.83 cm–1.17 Typical vibration peaks of C–F at 1400 −1000 cm–1 are observed.18 Among them, 1349.77 cm–1 corresponds to the absorption peak of CF2, and two strong peaks at 1189.82 and 1127.01 cm–1 correspond to the absorption peak of CF3. The absorption peaks of CH2=CF2 are at 1397.15 and 883.08 cm–1. In the spectra of CL-20, a vibration peak of the C–H bond in the ring appears at 3039.11 cm–1. At 1599.76 and 1327.81 cm–1, there are asymmetric stretching vibration peaks and symmetrical stretching vibration peaks of −NO2 groups, respectively. At 1267.46 cm–1, the vibration peak of the N–N bond is observed. At 1048.33 cm–1, the in-plane bending vibration peak of the ring is observed. A quartet of moderate intensity appears near 753.21 cm–1, which is the characteristic vibration peak of the ε-CL-20. The functional groups in F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9, 2:8, and 3:7 are consistent with the functional groups of F2602/GAP and CL-20, indicating that F2602/GAP and CL-20 are well combined.

Figure 3.

(a) IR spectra and (b) XRD spectra of samples.

The XRD spectrum (Figure 3b) shows that there are obvious diffraction peaks of CL-20 at 2θ = 10.66, 12.55, 13.75, 15.61, 16.24, 17.65, 19.93, 21.49, 21.91, 22.24, 22.63, 25.75, 27.82, 28.69, 30.28°, and so on, which are consistent with the standard spectrum of PDF#00-050-2045, and is ε-CL-20. The strong diffraction peaks of CL-20 at 2θ of 15.61, 16.24, 21.49, 21.91, 22.24, and 22.63° did not appear in F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9. The diffraction peaks 2θ of F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9 are 12.1, 13.75, 18.25, 19.03, 24.16, 24.94, 28.36, 30.34, and 36.76°, which are consistent with the diffraction peaks of β-CL-20, indicating that the crystal form of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 has changed after electrospinning.

Taking F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 3:7 as an example, XPS analysis was performed on F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fibers, and the results are shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that the characteristic peaks of C1s, N1s, O1s, and F1s are located at 290, 401, 533, and 687 eV, respectively. In the C1s spectrum of Figure 4(b), the peaks with binding energies of 284.4, 286, and 286.6 eV are attributed to C–C, C–N3, and C–O, respectively. The peak at 288.3 eV belongs to −C–F. The peaks at 289.4 and 290.8 eV correspond to −CF2 in perfluoropropylene and vinylidene fluoride, respectively. The peak at 293.3 eV belongs to the −CF3. In the N1s spectrum of Figure 4(c), the peaks with binding energies of 401.7 and 407.2 eV correspond to the C–N and −NO2 in CL-20, respectively. The peak at 400.5 eV belongs to −N=N=N. The peaks at 403.9 and 404.4 eV belong to −N=N=N. In the O1s spectrum of Figure 4(d), the peaks at 531.4 and 532 eV correspond to the C–O and −NO2, respectively. In the Figure 4(e) F1s spectrum, the fluorine element is present in the sample in the form of C–F (688.1 eV).

Figure 4.

XPS spectra of F2602/GAP/CL-20.

Taking F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 3:7 as an example, BET analysis was performed on the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber. Figure 5 shows the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber. The specific surface area, void volume, and pore diameter of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber are shown in Table 2. It can be seen from the figure that the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber is a typical type IV absorption curve, indicating that the prepared sample is a mesoporous material. At a higher P/P0, hysteresis can be observed due to capillary condensation, resulting in a H3-type hysteresis ring, indicating that the adsorbent hole is mainly conical.

Figure 5.

BET spectrum of F2602/GAP/CL-20.

Table 2. BET Surface Area and the Pore Structure Parameters of F2602/GAP/CL-20.

| sample | BET surface area (m2 g–1) | pore volume (cm3 g–1) | pore size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| F2602/GAP/CL-20 | 1.7296 | 0.000218 | 4.94122 |

2.2. Thermal Analysis

DSC analysis was performed on raw CL-20 and F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fibers with three proportions, as shown in Figure 6. It can be seen from Figure 6a that the CL-20 begins to decompose after 213 °C showing an obvious exothermic peak, and the peak temperature increases with the increase of the heating rate. As shown in Figure 6b-d with the increase of the proportion of F2602/GAP in the energetic fiber, the exothermic peak advances, which indicates that the activity of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber was higher than that of CL-20. In order to further study the thermal decomposition characteristics of the samples, the thermodynamic and kinetic parameters were calculated by using formulas 1–5, and the results are shown in Table 3.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

where Tp is the thermal decomposition peak temperature in the DSC spectrum when the heating rate is 15 °C·min–1; β is the heating rate; AK is the pre-exponential factor calculated by using the Kissinger equation; KB and h are the Boltzmann (KB = 1.381 × 10–23 J/K) and Planck constants (h = 6.626 × 10–34 J/s).

Figure 6.

(a-d) DSC spectra of the samples at four heating rates. (e) Kissinger plots of ln(β/Tp2) to 1000/Tp.

Table 3. Thermodynamics and Kinetics Derived from DSC Traces.

| thermodynamics |

kinetics |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | Tp (K) | ΔH≠ (kJ/mol) | ΔG≠ (kJ/mol) | ΔS≠ (J/mol·K) | EK (kJ/mol) | lnAK | k (s–1) |

| CL-20 | 510.35 | 171.34 | 122.40 | 95.90 | 175.59 | 34.62 | 1.16 |

| F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9 | 495.35 | 395.74 | 114.66 | 567.43 | 399.86 | 91.31 | 3.07 |

| F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 2:8 | 488.85 | 233.60 | 115.06 | 242.49 | 237.66 | 52.21 | 1.90 |

| F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 3:7 | 485.55 | 254.63 | 114.33 | 288.97 | 258.67 | 57.79 | 1.87 |

From the calculation results in the table, it can be seen that the activation free energies (ΔG≠) of the four samples are all positive values, indicating that they need to absorb energy instead of spontaneously during the process of changing from the normal state to the transition state. The thermal decomposition apparent activation energy (EK) of three different ratios of F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fibers is higher than that of CL-20, and the activation enthalpy (ΔH≠) of F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fibers is also significantly higher than that of CL-20, which indicates that the activation molecules of F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fibers heated to the transition state require more energy. Therefore, compared with CL-20, F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fibers have higher thermal stability. However, in three different ratios of F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fibers, the thermal stability from high to low is 1:9, 3:7, and 2:8. According to the rate constant (k), the decomposition rate of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber prepared based on F2602/GAP is faster than that of CL-20. In addition, the activation entropy (ΔS≠) of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber is significantly higher than that of CL-20, indicating that the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber has a higher degree of freedom after reaching the activated state from the normal state and is more easily decomposed into gas.

To analyze the product components of thermal decomposition of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber, taking F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9 as an example, the TG-MS test was performed from room temperature to 450 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. It can be seen from Figure 7 that the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber starts to decompose rapidly at 217.3 °C, and the loss of mass is about 75.7% at 241.5 °C after which the weight loss rate of the sample reaches the maximum at 235 °C.

Figure 7.

TG-MS spectra of F2602/GAP/CL-20.

Figure 7b shows ion peaks with mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) of 16, 18, 28, 30, 44, and 46, respectively. With the ion peak of m/z = 30 as the base peak, the relative strength of each ion peak was calculated, as shown in Figure 7c. The analysis shows that the thermal decomposition gas products of the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber are mainly C2H6, H2O, N2, and CO2, and a small amount of CH4, CO, NO, N2O, and NO2. Since the detection instrument can automatically filter corrosive substances, the ion peak of HF is not obtained, but the presence of corrosive gas HF in the sample product can be inferred from the corroded catheter.

2.3. Energy Performance and Sensitivities

Table 4 shows the mechanical sensitivity test results and energy performance results of the samples. The friction sensitivity results show that the explosion percentage (P) of F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9 is 52%, which is 38% lower than that of raw CL-20, while the explosion percentage of F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 2:8 and F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 3:7 is 0 in the 25-shot test. The impact sensitivity results show that the feature height (H50) of CL-20 is 21.2 cm. After spinning, the feature height of F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9 rises to 62.6 cm. This indicates that compared to CL-20, adding F2602/GAP can effectively lower its mechanical sensitivity.

Table 4. Impact Sensitivity and Energy Performance of the Samples.

| sensitivities |

energy performance |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | P/% | H50/cm | Isp/(N·s·kg–1) | C*/(m·s–1) | TC/K | –MW |

| CL-20(100%) | 84 | 21.2 | 2673.3 | 1638.0 | 3586.45 | 29.192 |

| F2602(5%)/GAP(5%)/CL-20(90%) | 52 | 62.6 | 2668.1 | 1667.2 | 3579.24 | 27.015 |

| F2602(10%)/GAP(10%)/CL-20(80%) | 0 | >90 | 2613.3 | 1670.7 | 3481.86 | 25.128 |

| F2602(15%)/GAP(15%)/CL-20(70%) | 0 | >90 | 2574.8 | 1651.3 | 3287.79 | 23.487 |

In Table 4, the theoretical specific impulse (Isp), characteristic velocity (C*), combustion chamber temperature (TC), and average molecular weight (MW) of the product are listed for the samples in the standard state with a combustion chamber pressure of 6.86 MPa and PC:P0 = 70. Figure 8 shows the molar ratio of the sample’s combustion products. It can be seen that the C* of F2602/GAP/CL-20 in different proportions is not much different but higher than that of CL-20 (100%), indicating that the energy released and work capacity of F2602/GAP/CL-20 under the same combustion chamber conditions are better than those of CL-20 (100%). It can be seen from Figure 8 that as the content of F2602/GAP increases, the contents of CO2 and H2O decrease, and the contents of CO and H2 increase. This is because the addition of F2602/GAP further reduces the oxygen balance of the system. Insufficient combustion in the F2602/GAP/CL-20 system becomes more obvious, so the average molecular weight (MW) of the product reduces. Although theoretically Isp is proportional to TC and inversely proportional to C*, the thermal energy reduction caused by the decrease of TC with the decrease of the CL-20 content in this system is much greater than the effect of C*. Thus, Isp of F2602/GAP/CL-20 decreases with the increase of the F2602/GAP content. F2602 (5%)/GAP (5%)/CL-20 (90%) has an Isp of 2668.1 N·s·kg–1, which is higher than the other two ratios of F2602/GAP/CL-20 and slightly lower than CL-20. In summary, the mechanical sensitivity of F2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9 is lower than that of CL-20, and at the same time, it has a higher specific impulse and has a good application prospect in solid propellants.

Figure 8.

Combustion products and their molar ratios of samples: (a) CL-20 (100%); (b) F2602(5%)/GAP(5%)/CL-20(90%); (c) F2602(10%)/GAP(10%)/CL-20(80%);and (d) F2602(15%)/GAP(15%)/CL-20(70%).

3. Conclusions

Three samples of F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fibers with F2602/GAP: CL-20 ratios of 1:9, 2:8, and 3:7 were prepared by electrostatic spinning. F2602/GAP/CL-20 has a three-dimensional network structure, and the average particle size is less than 1 μm. Moreover, the average diameter of the fiber increased with the increase of the proportion of F2602/GAP in F2602/GAP/CL-20, even when fiber breakage and hole production occurred. Structural analysis of the sample shows that the crystal form of CL-20 after spinning changed from ε-type to β-type. BET analysis shows that the prepared F2602/GAP/CL-20 was a mesoporous material. The thermal decomposition of F2602/GAP/CL-20 starts at about 217 °C. Its decomposition products were mainly C2H6, H2O, N2, and CO2 and a small amount of CH4, CO, NO, N2O, and NO2. The formation of HF is speculated. Compared with CL-20, the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber has a higher thermal stability. However, F2602/GAP: CL-20 = 1:9 has a higher activation energy and activation enthalpy than the other two proportions of fibers. Energy performance and safety are key indicators for evaluating energetic materials. The standard specific impulse (Isp) of F2602/GAP/CL-20 was slightly lower than that of CL-20, but it still maintains a high energy level. The mechanical sensitivity of CL-20 was significantly reduced by adding F2602/GAP. In summary, the fiberF2602/GAP:CL-20 = 1:9 has a uniform particle size distribution and a smooth surface, which not only improves the safety of CL-20 but also contributes to a high specific impulse (Isp). It provides a new idea for the formulation design of composite propellants.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

Hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane (CL-20) was provided by Gansu Yinguang Chemical Co., Ltd. (Baiyin city, Gansu province, P.R. China). Glycidyl azide polymer (GAP, Mn = 4000, hydroxyl value of 0.49 mmol·g–1) was obtained from the 42nd Institute of the Fourth Academy of China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. Fluoroelastomers (F2602) were purchased from Dongguan Baojulai Plastic Materials Co., Ltd. Acetone was purchased from Tianjin Guangfu Chemical Co., Ltd. (Tianjin city, China), which was a copolymer of perfluoropropylene and vinylidene fluoride.

4.2. Preparation Process

F2602, GAP, and CL-20 were added into three small beakers at ratios of F2602/GAP: CL-20 = 1:9, 2:8, and 3:7, respectively, followed by the addition of an appropriate amount of acetone, and the mixture was stirred evenly to obtain a F2602/GAP/CL-20 precursor solution (20 wt %). The prepared F2602/GAP/CL-20 precursor solution (20 wt %) was drawn into a syringe as the supplied device, aluminum foil served as the receiving device, the applied voltage was maintained at 10–20kv, the injection rate was set at 5 mL/h, and the fiber receiving distance was 12 cm. Then, the F2602/GAP/CL-20 energetic fiber was prepared by spinning. The F2602/GAP precursor solution (20 wt %) was obtained by weighing the same amount of F2602 and GAP in the same way as above, adding an appropriate amount of acetone, and then the F2602/GAP complex was prepared by spinning.

4.3. Characterization

The morphology of the samples was analyzed by SEM and EDS. The structure of the samples was analyzed by BET and XRD. The composition of the samples was analyzed by IR and XPS. DSC and TG-MS were used for thermal testing. The samples were tested for friction sensitivity, and energy performance calculations were carried out. The instruments used were as follows: an MIRA 3 LMH scanning electron microscope (resolution: 1 nm, magnification: ∼1 million times, and acceleration voltage: 200–30 kV). Nano Measurer 1.2 software was used to calculate the particle size distribution of the samples. An advance D8 X-ray powder diffractometer (Brook, Germany, using Cu Ka target radiation, tube voltage: 40 kV, and current: 30 mA), an infrared spectrometer (American Thermo Fisher Scientific Nicolet 6700), and an X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (Ulvac Japan, PHI5000 Versa-Probe) were used. BET nitrogen adsorption studies using a Micromeritics ASAP 2010 instrument were performed. An STA 499 F3 synchronous thermal analyzer and a QMS 403 C mass spectrometer (Netzsch, Germany) were used, and the heating rate was 10 °C·min–1. A synchronous thermal analyzer (Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) was used, heating rates were 5, 10, 15, and 20 °C·min–1, the sample size was 5 mg, and a ceramic crucible was used. MGY-Ifriction sensitivity instrument, refer to 601.4 method in GJB772A-97, swing angle is 90°, 3.92 MPa, 25 samples each time. The impact sensitivity test was conducted according to GJB772A-97 method 601.3. The drop weight was 2.5 kg, and the dose was 35 mg. American NASA-CEA software was used to calculate energy performance.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Weapon Equipment Pre-Research Fund of China (grant no. 6140656020201).

Author Contributions

X. S. and Y. W. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Nielsen A. T.Caged polynitramine compound. US Patent, US 5,693,794 A, 1997.

- Sider A. K.; Sikder N.; Gandhe B. R. Hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane or CL-20 in India: synthesis and characterisation. Defence Sci. J. 2012, 52, 135–146. 10.14429/dsj.52.2158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qu C. X.; Ge Z. X.; Zhang M. Research progress on sensitivity decrease methods of hexanitro-hexaazaisowurtzitane. Chem. Reagents 2019, 41, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. X.; Wang C. D.; Pan H. B. Process in the research into energetic azide polymer binders. Polym. Bull. 2014, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ye B. Y.; Wang J. Y.; An C. W. Preparation and properties of CL-20 based composite energetic material. J. Solid Rocket Tech. 2017, 2, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jin S. H.; Yu S. X.; Ou Y. X. Investigation of coating-desensitization of hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane (HNIW). Chinese J. Energ. Mater. 2004, 12, 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Bao G. L.; Zhang J. P.; Zhao W. Study on preparation of the nanofibers by electrospinning. Contemporary Chem. Indust. 2014, 43, 2632–2635. [Google Scholar]

- Yan S.; Li M.; Sun L.; Jiao Q.; Huang R. Fabrication of nano- and micron- sized spheres of CL-20 by electrospray. Cent. Eur. J. Energ. Mater. 2018, 15, 572–589. 10.22211/cejem/100682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo T.; Wang Y.; Huang H.; Shang F.; Song X. An electrospun preparation of the NC/GAP/nano-LLM-105 nanofiber and its properties. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 854. 10.3390/nano9060854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J.; Li B.; Xie L. F. Electrospray preparation and properties of RDX/F2604 composites. J. Energ. Mater. 2017, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T. H.; Liu F. X.; Hua X. H. Preparation and properties of the F2604/AP composite. Explos. Mater. 2017, 46, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T. Fabrication of porous structure of electro-spun PVDF fibres. J. Adv. in Nanomaterials 2018, 3, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. F. Materials in aerospace industry. Mater. China 2013, 32, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hou C. H.; Jia X. L.; Wang J. Y.; Tang Y.; Zhang Y.; Chao L. Efficient preparation and performance characterization of the HMX/F2602, microspheres by one-step granulation process. J. Nanomaterials 2017, 2017, 3607383. 10.1155/2017/3607383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bian H. L.; Li X. D.; Shi X. F. Preparation and characterization of HMX/F2602 nano energetic microspheres. Sci. Techn. Eng. 2017, 17, 196–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ji W.; Li X.; Wang J.; Ye B.; Wang C. Preparation and characterization of the solid spherical HMX/F2602 by the suspension spray-drying method. J. Energ. Mater. 2016, 34, 357–367. 10.1080/07370652.2015.1095813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L.; Yun N.; Geng X. H. Synthesis and characterization of glycidyl azide polymer. J. North Univer. China 2014, 35, 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Han W. X. Analysis and identification of fluorine rubber type. Special Purpose Rubber Products 2012, 64–67. [Google Scholar]