Abstract

Starch content is an important parameter indicating the state of harvest maturity of fresh cassava root. Nowadays, the methods used for estimating the starch content in the field are the measurement of root weight, size, or snapping force. These methods are simple but the results are rather incorrect. For this reason, a developed portable visible and near-infrared spectrometer(350–1050 nm) was used to estimate rapidly and nondestructively starch content in fresh cassava root. The best starch prediction model received from the full wavelength region was able to predict the starch content with a correlation coefficient of prediction (rp) of 0.825, standard errors of prediction of 2.502%, and bias of −0.115%. Moreover, the predicted values were not significantly different from the actual values obtained from the standard method at 95% confidence intervals. It was also noted that the top position of the root was a good representative for starch prediction. In addition, this position was easy to be measured in the field before harvesting.

Introduction

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is cultivated and consumed in many countries across Africa, Asia, and South America because it is a drought-resistant root which offers a low-cost vegetative propagation with flexibility in harvesting time and seasons. The cassava is a starchy fibrous root, rich in carbohydrate content, which ranges from 32 to 35% in fresh weight and about 80–90% in dry matter.1 Presently, the cassava attracts great worldwide attention because its starch is an important source of raw materials for fuel ethanol production2,3 and other industries. Therefore, the starch content is the important trait in the cassava roots because it is used for pricing purchase. Harvesting of roots with low-starch content has an effect on both cassava growers and tapioca starch manufacturers. The growers suffer by losing money and it is also less beneficial for manufacturers.

The cassava growers in Thailand typically determine root maturity based on time of cultivation and root size before harvest. Some cultivars of cassava can be harvested as early as 6 months after cultivation. However, most cassava varieties are harvested at around 8–12 months. Sometimes, a subjective evaluation method is done by selecting a medium-sized root and snapping it. If the root is snapped with medium force, it is generally regarded as mature and the flesh will be firm, white, and dry. That root is considered to have the maximum starch content (approximately 30%). Low starch flesh from immature roots is usually slightly yellow and has a translucent watery core. If considerable force is required to snap the tuber, it is considered to become woody and the root is undesirable for starch factories. However, these methods are a rough prediction and consequently do not reflect the exact starch levels.4 Rapid assessment of the starch content in the roots at the field can help cassava growers and manufacturers determine the starch yield in the roots before and after harvest.

Near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy is one of the most promising methods, which is a rapid and nondestructive technique. Moreover, this technique can determine numerous constituents simultaneously. Therefore, it is frequently used for both qualitative and quantitative analysis in agriculture and industry. NIR spectroscopy has been reported for achieving excellent predictions of flour samples from tropical root and tuber crops for major constituents.5 This method was sufficiently accurate and effective for rapid evaluation of sweet potato starch physiochemical quality and pasting properties.6 Furthermore, this technique is used to assess the quality of the raw material. The results show that the NIR measurement of mashed crude potatoes could well predict the starch and protein parameters.7 From more than 3000 samples, the ground cassava root was used to evaluate the potential of NIR to predict root quality traits. NIR predictions were highly satisfactory for dry matter content, total carotenoids, and β-carotene.8 All results showed that the technique looked attractive for cassava, especially for starch, which is an important parameter as mentioned above. In previous studies, the fresh samples were prepared by chopping or grinding and homogenized, which is not suitable for rapid starch assessment at the field. Abundant studies have been reported in recent years on using visible and NIR (vis/NIR) spectroscopy for fast measurement of constituents and other quality attributes of intact agricultural products, for example, potato,9 banana and mango,10 Valencia orange,11 cucumber,12 and sugar beet.13 However, there has been no research reported on measuring the starch content of intact fresh cassava roots using vis/NIR spectroscopy.

Therefore, this research aimed to study the feasibility of portable vis/NIR spectrometers operated in interactance mode in the spectral regions of 350–1050 nm for predicting the starch content of fresh cassava roots. Moreover, the performance of the calibration model was evaluated according to ISO 12099:2017(E). The effect of the position for spectral measurement on predicting starch content in fresh cassava roots was also determined.

Results and Discussion

Prior to calibration development, interference in the spectral data was evaluated. The presence of interference affects the signal-to-noise ratio. Therefore, it is necessary to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, de-noising, remove background, and increase spectral resolution. The smoothing by moving average confirmed the best de-noising method for vis/NIR spectral data.14,15 First of all, the spectral data were pretreated by smoothing. The smoothing was also expected to correct additive and multiplicative effects in the spectral data, while still preserving the important features of information as shown in Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

(a) Absorbance and (b) second-derivative spectra of fresh cassava roots.

Figure 1 shows the vis/NIR absorbance spectra of fresh cassava root and its second derivative in the ranges of 350–1050 nm. Two dominant absorption regions were observed in all absorbance spectra (Figure 1a), which were around 420–450 and 490 nm. As the spectra of cassava roots were shifting because of the difference of peel thickness in each sample, a second derivative pretreatment was applied to suppress the effect and separate overlapped peaks. Three upside-down major peaks were observed in their second derivative spectra (Figure 1b), two of which (around 435 and 490 nm) were similar to the original spectra and the other was at 968 nm, which was found only in second derivative spectra. In order to identify the absorption bands of cassava starch, the spectrum of commercial tapioca starch was measured by the device in the ranges of 350–1050 nm. The average spectrum of second derivative spectra of commercial tapioca starch is shown in Figure 2. The spectrum showed a similar absorption peak with fresh cassava root (Figure 1b). The absorption peaks were also found in the visible region at around 435 nm with respect to the absorbance of commercial tapioca starch and a strong peak around 490 nm because of the starch content. The absorbance at 490 nm was generally used to determine starch contents by a UV/visible spectrophotometer.16 In the NIR region between 700 and 1050 nm, absorption mainly came from the third overtone and second overtone of both C–H (915 nm) and O–H (968 nm), which are starch and water, respectively.17

Figure 2.

Second derivative spectrum of commercial tapioca starch measured in the region of 350–1050 nm.

The statistical parameters of the starch content in the calibration set and the validation set are shown in Table 1. Calibration equations were developed by using partial least squares (PLS) regression with no-pretreatment, first derivative and second derivative pretreatment of the spectra. The ranges of 350–1050 nm (full wavelength) and 700–1050 nm were also used. The results of PLS models for starch content determination of fresh cassava roots are summarized in Table 2. The best calibration equation was achieved from second derivative spectra at 350–1050 nm with a correlation coefficient of prediction (rp) of 0.825 and standard error of prediction (SEP) of 2.502%. This model could yield a slightly better prediction of starch content than the one from 700 to 1050 nm.

Table 1. Statistics of Starch Contents in Each Sample Set.

| starch

content (% FW)a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample set | number of samples | minimum | maximum | average | SD |

| calibration set | 135 | 19.91 | 42.84 | 33.16 | 4.42 |

| validation set | 45 | 21.74 | 39.51 | 32.64 | 4.36 |

FW: fresh weight basis.

Table 2. Statistics of PLS Models for Starch Content Determination of Fresh Cassava Roots at Two Wavelength Ranges of 350–1050 and 700–1050 nma.

| calibration

set |

validation

set |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| spectral range (nm) | pretreatment | LVs | rc | SEC (% FW) | rp | SEP (% FW) | bias (% FW) | slope |

| 350–1050 | no | 10 | 0.808 | 2.599 | 0.794 | 2.716 | –0.170 | 0.8533 |

| first derivative | 10 | 0.836 | 2.426 | 0.812 | 2.638 | –0.001 | 0.8363 | |

| second derivative | 10 | 0.841 | 2.388 | 0.825 | 2.502 | –0.115 | 0.8972 | |

| 700–1050 | no | 8 | 0.695 | 3.175 | 0.607 | 3.668 | 0.233 | 0.6884 |

| first derivative | 7 | 0.698 | 3.161 | 0.679 | 3.295 | 0.375 | 0.7920 | |

| second derivative | 9 | 0.708 | 3.119 | 0.718 | 3.093 | 0.441 | 0.8395 | |

LVs: number of latent variables in calibration equation, rc: correlation coefficient of calibration, FW: fresh weight basis, SEC: standard error of calibration, rp: correlation coefficient of prediction, SEP: standard error of prediction, bias: the average of the residual.

The results of starch content prediction in the validation set are shown in Figure 3. Deviation of samples is visualized in a scatter plot of correlation between the measured and predicted values of starch content using spectral data in two wavelength ranges of 350–1050 and 700–1050 nm. The results indicated that the correlation coefficient of the validation set were 0.825 and 0.718, the SEP were 2.502 and 3.093%, and the bias were −0.115 and 0.441% for wavelength region of 350–1050 nm (Figure 3a) and 700–1050 nm (Figure 3b), respectively. The calibration equation for starch content of fresh cassava root illustrated good accuracy. When comparing the results of the model developed using the vis/NIR regions versus the model developed for NIR regions, it was observed that the best result was obtained from vis/NIR regions. Similar studies have already been conducted to determine sucrose content in sugar beet. The correlation coefficient for the spectral regions of 400–1100 and 900–1600 nm was 0.80 and 0.74, whereas SEP was 0.89 and 1.02%, respectively.13 Additionally, previous researches have been reported on intact oranges using two wavelength ranges of 450–1000 and 700–1000 nm. The results of soluble solids content prediction for intact oranges provided rp of 0.937 and 0.944, root mean squared error of prediction of 0.321 and 0.309, respectively.11 Those results clearly demonstrated that vis/NIR could be effectively used for internal quality determination.

Figure 3.

Scatter plots between predicted and actual values of starch content for the validation data set using models developed in wavelength range of (a) 350–1050 and (b) 700–1050 nm.

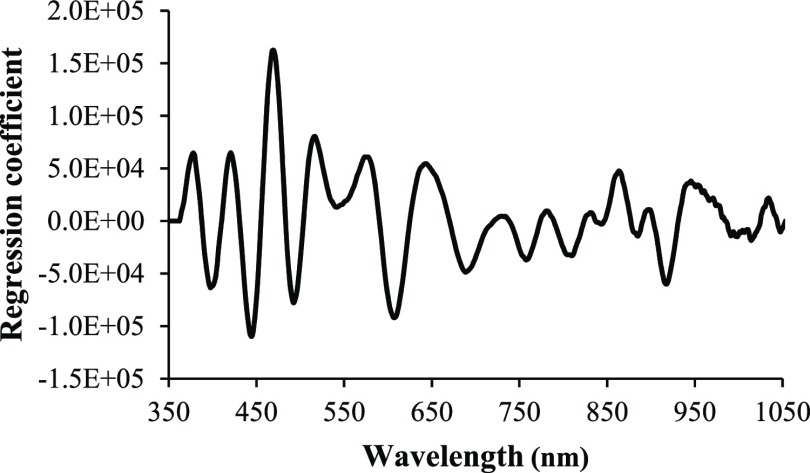

The regression coefficient of starch content of fresh cassava roots can be analyzed to evaluate influential variables used in the equation because spectra variations at different wavelengths reflect the information regarding different functional groups of the measured components.18 The two major components of starch are amylose and amylopectin. Amylose consists mainly of α-(1–4)-linked-d-glucopyranosyl residues, whereas amylopectin is composed of linear chains of (1–4)-α-d-glucose residues connected through (1–6)-α-linkages.19 Thus, the starch is composed of the molecular bonds of C–H, O–H, C–C, and C–O. Figure 4 shows the regression coefficient plot of the calibration equation obtained from vis/NIR regions. In total, four major negative peaks were found, which were at 443, 490, 608, and 915 nm. The peaks at 443 nm (440 nm),20 490 nm, and 608 nm (612 nm)21 correspond to the absorption band of amylose. The last peak at 915 nm corresponded to the third overtone of C–H stretching. In addition, the performance test of a calibration equation was evaluated according to ISO 12099:2017(E). Table 3 shows the statistics for performance measurement. It was found that the bias was lower than Tb = ±0.752, indicating that the bias was not significantly different from 0. The SEP was lower than TUE = 2.901, indicating that SEP was low enough for practical acceptance. Moreover, tobs calculated according to the equation for the slope test (1.095) was lower than t(1−α/2) = 2.015, which was obtained from the value of the t-distribution with a probability of α = 0.05. It indicated that the slope was not significantly different from 1. Hence, the results showed that the predicted starch content values were not significantly different from actual values at 95% confident intervals. It indicates that this calibration model could be used for determining the starch content without a destruction of cassava roots and screening large numbers of samples in a short period of time.

Figure 4.

Regression coefficient plot of calibration equation obtained from vis/NIR regions based on PLS for starch content determination in fresh cassava root.

Table 3. Statistics of Model Performance Measurement Followed in ISO 12099:2017(E)a.

| parameters | criterion | calculated value | result |

|---|---|---|---|

| bias | Tb = ±0.752 | –0.115 | pass |

| SEP | TUE = 2.901 | 2.502 | pass |

| tobs for slope test | t(1−α/2) = 2.015 | 1.095 | pass |

In order to verify whether the position of the root can be ignored or not, the best model was used for predicting the starch content of the prediction set at the top, the middle, and the end position of the cassava root. A total of 20 samples were newly selected for the prediction set and starch values ranged from 23.44 to 38.72%. The plots of reference values versus predicted values in the prediction set calculated by the best model are shown in Figure 5. The results indicated that the prediction at the middle position seemed slightly better than those obtained by the other positions with the highest r (0.848) and lowest SEP (2.113%). However, the nonsignificant difference between the reference and predicted values at each position (p > 0.05) (Table 4) indicated that the measuring position (top, middle, and end) has no effect on starch determination. As the top position is easy to measure, this position will be effective for prescreening starch content of cassava roots in the field before harvesting.

Figure 5.

Reference versus predicted values plots for starch content in cassava root measured at the (a) top, (b) middle, and (c) end positions.

Table 4. Paired t-Test between Reference and Predicted Values for Starch Content Prediction in Each Position of the Cassava Root.

| positions | number of samples | t-value | P-value | significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| top | 20 | –0.15 | 0.88 | NS |

| middle | 20 | –0.77 | 0.45 | NS |

| bottom | 20 | 0.64 | 0.53 | NS |

Conclusions

The feasibility of utilizing a developed portable vis/NIR spectrometer was evaluated for starch content assessment of fresh cassava root. The developed calibration equation could predict starch content accurately with a correlation (rp) of 0.825, SEP of 2.502%, and bias of −0.115%. Furthermore, the position of spectral measurement did not affect the predicted starch content at the 5% level of significance. Therefore, vis/NIR in interactance mode can be used to predict the starch content for fresh cassava root with an acceptable accuracy.

Materials and Methods

Cassava Root Samples

The cassava roots used in this experiment were harvested from farmers’ fields in Ratchaburi and Kanchanaburi provinces in Thailand where there are different soil types and climatic conditions. Field treatments were done according to typical local farmers’ protocols. The mature roots were harvested after 8–12 months of plantation. A total of 180 root samples consisting of four commercial varieties, which were Kasetsart 50, Rayong 5, Rayong 11, and Huaybong 80, were used in the study. These varieties are certified from the Department of Agriculture, the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, Thailand. The samples were washed to remove adhered soil before experimenting. It was noted that a brownish outer layer, the periderm, about 1 mm thick of some varieties would come off easily while being washed. Therefore, this brownish outer layer was peeled off around the collected spectra positions by a kitchen knife (Figure 6a). After cleaning, the samples were air-dried at ambient temperature for 24 h to remove adhered water before spectral measurements.

Figure 6.

Spectra acquisition of the (a) cassava root at six positions on the samples using (b) a portable device for 350–1050 nm.

Vis/NIR Spectra Measurements

The cassava roots were measured using a portable device invented by the Near Infrared Technology Laboratory, Department of Food Engineering, Faculty of Engineering at Kamphaeng Saen, Kasetsart University, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand (Figure 6b). The device collected spectral information between 350 and 1050 nm with a resolution of 1.5 nm. The tungsten halogen light source with a power of 20 W was used. For measuring the spectra of cassava roots, a bifurcated interactance probe was used to transfer light from the light source to the sample and reflected light from the sample to the detector mounted in the device. Reference spectra were acquired from a white ceramic plate measurement in order to calculate the relative absorbance of each root sample.

For each sample, the spectra measurements were taken at six positions along the cassava root and around equatorial locations on the sample (Figure 6a) and the average of these spectra was calculated. In each position, spectra measurements were done in duplicate using an integration time of 50 ms. During measurement, the probe was placed perpendicularly against the surface in order to prevent external light interference.

Reference Measurement

After spectra measurements, each cassava root including the peel were chopped with a knife into a 0.2–0.5 cm3 portion. The sample was divided for moisture and starch content analysis. Five grams of the chopped sample were used to analyze the moisture content, which was dried in an oven at 105 °C for 5 h.22 Each sample was done in duplicate. To preserve the samples before sending them for starch content analysis, the remaining samples were oven-dried at 50 °C for 24 h (moisture content lower than 12%).23 The dried samples were ground into flour just after oven-drying. In order to achieve the homogenized sample, ground samples were passed through four sieves (mesh no. 10, no. 12, no. 16, and no. 25) until their particle size was less than 0.707 mm. One hundred grams of flour samples were packed into a vacuum bag and sent to the Cassava and Starch Technology Research Unit, National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, National Science and Technology Development Agency, Thailand, for starch content analysis using the polarimetric method of the European Economic Community. The sample (5.0000 g) was put in a 200 mL volumetric flask and added with 50 mL of 1.128% hydrochloric acid. The flask was shaken until the sample was saturated and then a further 50 mL of 1.128% hydrochloric acid was added. Next, the sample in the flask was immersed in a boiling water bath and swirled vigorously for 3 min to prevent flocculation. After 15 min, the flask was removed from the boiling water bath, 60 mL of cold water was added, and it was cooled immediately to 20 °C. Then, 20 mL of sodium phosphotungstate solution or dodecaphosphotungstic acid was added into the flask and shaken vigorously for the forming of the precipitate. After adjusting the volume with 20 °C distilled water, the solution was mixed thoroughly and filtered through a dry filter paper (Whatman no. 1). The first 25 mL of the filtrate was discarded. The following filtrate was transferred to a 100 mm tube of the polarimeter (Polartronic MH8, Schmidt + Haensch, Germany). A specific optical rotation of 184.0° was used for calculation.

Data Processing and Calibration Equation Development

The chemometrics software package, the Unscrambler v9.7 (CAMO Software AS, Norway), was used for PLS regression. All 180 cassava root samples were randomly separated into two sets with 75% for the calibration set (135 samples) and the remaining 25% for the validation set (45 samples). Calibration models were developed using PLS regression based on the full range vis/NIR spectra (350–1050 nm) and NIR spectra (700–1050 nm). Two standard data preprocessing methods, which were first derivatives and second derivatives, were applied to remove baseline offset and the tangent (linear background) arising from scattering effects. The model performance was evaluated by comparing the prediction results and measured values in the validation sets. Statistical parameters including correlation coefficient of the calibration set (rc) and the validation set (rp), the standard error for the calibration (SEC) prediction (SEP) data sets and bias were calculated. These parameters were used to assess the performance of each calibration model for predicting the starch content of the roots.

Model Performance Measurement

The performance of a prediction model shall be determined by a set of validation samples according to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 12099:2017(E) for Animal feeding stuffs, cereals, and milled cereal products—guidelines for the NIR spectrometry.24 Statistical parameters for performance measurement are bias, SEP, and slope. The significance of the bias is checked by a t-test. If the bias value is less than the bias confidence limits (BCLs), the bias is not significantly different from zero. The calculation of BCLs or Tb is defined in eq 1.

| 1 |

The SEP expresses the accuracy of routine NIR results corrected for the mean difference (bias) between routine NIR and the reference method. If SEP is less than the unexplained error confidence limits (TUE), the SEP can be accepted, whereas TUE are calculated from an F-test as

| 2 |

where α is the probability of making a type I error; t is the appropriate Student t-value for a two-tailed test with degrees of freedom associated with SEP and the selected probability of a type I error; n is the number of independent samples; SEP is the standard error of prediction. SEC is the standard error of calibration; ν = n – 1 is the numerator degrees of freedom associated with SEP of the test set, in which n in the number of samples in the validation process; M = nc – p – 1 is the denominator degrees of freedom associated with SEC; in which nc is the number of calibration samples, p is the number of terms or PLS factors of the model.

The slope, b, of the simple regression y = a + bŷ is often reported in NIR publications. The slope must be calculated with the reference values as the dependent variable and the predicted NIR values as the independent variable. From the least squares fitting, the slope is calculated as

| 3 |

where sŷy is the covariance between reference and predicted values; sŷ2 is the variance of n predicted values.

The intercept is calculated as

| 4 |

where y̅ is the mean

of the reference values;  is the mean of the predicted

values; b is the slope. As for the bias, a t-test

can be calculated to check the hypothesis that b =

1

is the mean of the predicted

values; b is the slope. As for the bias, a t-test

can be calculated to check the hypothesis that b =

1

| 5 |

where b is the slope; n is the number of independent samples; sŷ2 is the variance of the n predicted values; sres is the residual standard deviation as defined in

| 6 |

where a is the intercept eq 4; b is the slope eq 3; yi is the ith reference value; ŷi is the ith predicted value obtained when applying the multivariate NIR model.

The slope, b, is considered as different from 1 when tobs ≥ t(1−α/2), where tobs is the observed t-value, calculated according to eq 5; t(1−α/2) is the t-value obtained from table t-distribution for a probability of α = 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Graduate Program Scholarship from the Graduate School, Kasetsart University. The authors are grateful to the Department of Internal Trade, Ministry of Commerce for their support and the Banpong Tapioca Flour Industrial Co., Ltd. for providing cassava root samples and other facilities.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

The photos in Figure 6 and the TOC were taken by Y.B.

References

- Uchechukwu-Agua A. D.; Caleb O. J.; Opara U. L. Postharvest handling and storage of fresh cassava root and products: a review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2015, 8, 729–748. 10.1007/s11947-015-1478-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papong S.; Malakul P. Life-cycle energy and environmental analysis of bioethanol production from cassava in Thailand. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, S112–S118. 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziska L. H.; Runion G. B.; Tomecek M.; Prior S. A.; Torbet H. A.; Sicher R. An evaluation of cassava, sweet potato and field corn as potential carbohydrate sources for bioethanol production in Alabama and Maryland. Biomass Bioenergy 2009, 33, 1503–1508. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2009.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grace M. R.Cassava processing, http://www.fao.org/docrep/x5032e/x5032E00.htm (accessed Dec 17, 2018).

- Lebot V.; Champagne A.; Malapa R.; Shiley D. NIR determination of major constituents in tropical root and tuber crop flours. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10539–10547. 10.1021/jf902675n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G.; Huang H.; Zhang D. Prediction of sweetpotato starch physiochemical quality and pasting properties using near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2006, 94, 632–639. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haase N. U. Rapid estimation of potato tuber quality by near-infrared spectroscopy. Starch/Stärke 2006, 58, 268–273. 10.1002/star.200500403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez T.; Ceballos H.; Dufour D.; Ortiz D.; Morante N.; Calle F.; Zum Felde T.; Domínguez M.; Davrieux F. Prediction of carotenoids, cyanide and dry matter contents in fresh cassava root using NIRS and hunter color techniques. Food Chem. 2014, 151, 444–451. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. Y.; Zhang H.; Miao Y.; Asakura M. Nondestructive determination of sugar content in potato tubers using visible and near infrared spectroscopy. Jpn. J. Food Eng. 2010, 11, 59–64. 10.11301/jsfe.11.59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subedi P. P.; Walsh K. B. Assessment of sugar and starch in intact banana and mango fruit by SWNIR spectroscopy. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 62, 238–245. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2011.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidi B.; Minaei S.; Mohajerani E.; Ghassemian H. Prediction of soluble solids in oranges using visible/near-infrared spectroscopy: effect of peel. Int. J. Food Prop. 2014, 17, 1460–1468. 10.1080/10942912.2012.717332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidi B.; Mohajerani E.; jamshidi J.; Minaei S.; Sharifi A. Non-destructive detection of pesticide residues in cucumber using visible/near-infrared spectroscopy. Food Addit. Contam., Part A 2015, 32, 857–863. 10.1080/19440049.2015.1031192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L.; Zhu Q.; Lu R.; McGrath J. M. Determination of sucrose content in sugar beet by portable visible and near-infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2015, 167, 264–271. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makky M.; Soni P. In situ quality assessment of intact oil palm fresh fruit bunches using rapid portable non-contact and non-destructive approach. J. Food Eng. 2014, 120, 248–259. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moghimi A.; Aghkhani M. H.; Sazgarnia A.; Sarmad M. Vis/NIR spectroscopy and chemometrics for the prediction of soluble solids content and acidity (pH) of kiwifruit. Biosyst. Eng. 2010, 106, 295–302. 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2010.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oboh G.; Ademosun A. O.; Akinleye M.; Omojokun O. S.; Boligon A. A.; Athayde M. L. Starch composition, glycemic indices, phenolic constituents, and antioxidative and antidiabetic properties of some common tropical fruits. J. Ethnic Foods 2015, 2, 64–73. 10.1016/j.jef.2015.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne B. G.; Fearn T.; Hindle P. H.. Practical NIR Spectroscopy with Applications in Food and Beverage Analysis; Longman Singapore Publisher (Pte) Ltd.: Singapore, 1993; p 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi T. B.; Sharma S.; Chattopadhyay K. Development of NIRS models to predict protein and amylose content of brown rice and proximate compositions of rice bran. Food Chem. 2016, 191, 21–27. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover R. Composition, molecular structure, and physicochemical properties of tuber and root starches: a review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2001, 45, 253–267. 10.1016/s0144-8617(00)00260-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J.; Jiang Q.; Zhang X.; Wei L.; Chen G.; Qi P.; Wei Y.; Lan X.; Lu Z.; Zheng Y. Effect of lipids on starch determination through various methods. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 51, 751–757. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson C. A. Evaluation of variations in amylose–iodine absorbance spectra. Carbohydr. Polym. 2000, 42, 65–72. 10.1016/s0144-8617(99)00126-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thai Industrial Standard. TIS 52-1973; Tapioca Products: Thailand, 1973; pp 6–7.

- Cassava and Starch Technology Research Unit . Sample Preparation of Dried Cassava Roots for Chemical Composition Analysis; Kasetsart Agricultural and Agro-Industrial Product Improvement Institute, Kasetsart University: Thailand, 2016; pp 1.

- International Standard . Statistics for performance measurement. ISO 12099:2017(E): Animal Feeding Stuffs, Cereals and Milled Cereal Products—Guidelines for Application of Near Infrared Spectrometer: Switzerland, 2017; pp 5–12.