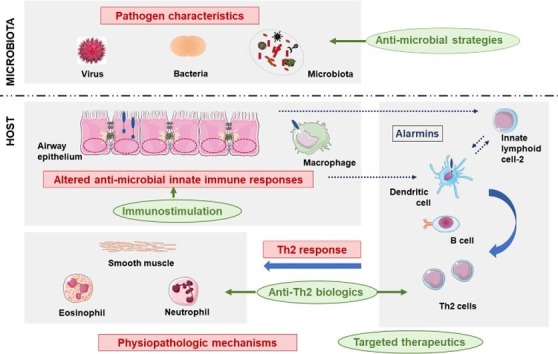

Graphical abstract

Characteristics of host-microbiota interactions in asthmatic children favor asthma attacks and may allow to define asthma endotypes.

This knowledge offers promising perspectives to treat asthmatic children using precision medicine.

Keywords: Acute asthma, Asthma exacerbation, Childhood, Virus, Microbiota, Therapeutics

Abstract

Exacerbations are a main characteristic of asthma. In childhood, the risk is increasing with severity. Exacerbations are a strong phenotypic marker, particularly of severe and therapy-resistant asthma. These early-life events may influence the evolution and be involved in lung function decline.

In children, asthma attacks are facilitated by exposure to allergens and pollutants, but are mainly triggered by microbial agents. Multiple studies have assessed immune responses to viruses, and to a lesser extend bacteria, during asthma exacerbation. Research has identified impairment of innate immune responses in children, related to altered pathogen recognition, interferon release, or anti-viral response. Influence of this host-microbiota dialog on the adaptive immune response may be crucial, leading to the development of biased T helper (Th)2 inflammation. These dynamic interactions may impact the presentations of asthma attacks, and have long-term consequences.

The aim of this review is to synthesize studies exploring immune mechanisms impairment against viruses and bacteria promoting asthma attacks in children. The potential influence of the nature of infectious agents and/or preexisting microbiota on the development of exacerbation is also addressed. We then discuss our understanding of how these diverse host-microbiota interactions in children may account for the heterogeneity of endotypes and clinical presentations. Finally, improving the knowledge of the pathophysiological processes induced by infections has led to offer new opportunities for the development of preventive or curative therapeutics for acute asthma. A better definition of asthma endotypes associated with precision medicine might lead to substantial progress in the management of severe childhood asthma.

1. Introduction

Childhood asthma is a major public health issue in industrialized countries. Development and progression of the disease is marked by exacerbations, also called asthma attacks, which are one of the most prevalent causes of hospitalization in children with consequently significant costs worldwide [1], [2], [3]. They constitute key events in the natural history of childhood asthma and are major markers of its heterogeneity [4]. Mechanisms leading to asthma attacks are not fully understood and may differ between children, according to their age range or phenotype.

Pediatric literature on asthma usually distinguishes preschool recurrent wheeze/also called preschool asthma in children aged 5 years and younger; from school-age children asthma, in those aged 6–11 years; and adolescent asthma, in those aged 12–17 years [3], [5], [6]. During preschool years, these events can be isolated, with few or no interval symptoms, and their persistence despite conventional maintenance treatment, such as inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), is a marker of severity [6], [7]. Although viral infections are the main triggers of acute asthma, early and multiple allergic sensitization is a strong risk factor of presenting severe and frequent exacerbations [7], [8]. In school-age children and adolescents, acute asthma attacks are usually less frequent, and not only triggered by lung infections, but also by exposure to allergens and pollutants [3], [9], [10]. Exacerbations rates increase with the severity of the disease, which is defined according to treatment pressure to obtain asthma control [4], [5]. Repetition of frequent and severe episodes under high doses of ICS associated with another maintenance treatment (mainly long acting beta2 agonists) is a criteria of severe asthma in these age-groups [11], [12], as demonstrated in pediatric asthma cohorts [13], [14]. Additionally, it is now recognized that patients prone to exacerbations constitute a distinct susceptibility phenotype, possibly associated with different endotypes, including specific airway inflammation patterns, or inflammatory mechanisms in response to infectious agents [15]. In some individuals, the severity of the disease and propensity to develop acute asthma may also vary throughout the course of childhood [16]. These early-life events can influence the long-term evolution at adult-age, in terms of asthma persistence, phenotype and alterations of lung function, that may lead to early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [17]. Early interventions could modify the natural history of the disease. However, in children with severe asthma, conventional maintenance therapies may be insufficient to prevent asthma attacks [7], [18], and repeated or prolonged oral corticosteroids are associated with many side effects, such as defective growth [19]. New treatment strategies are now needed. Interestingly, some studies have shown the efficacy of biologics in pediatric asthma, mainly on severe exacerbations, and suggested disease-modifying properties of some of them, making it a particularly attractive strategy in children [20].

Viruses are closely linked to wheezing illnesses during early childhood [21]. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and rhinoviruses (RV), both RNA viruses, are among the most common causes of lower respiratory tract infections, i.e. bronchiolitis and/or pneumonia, with a predominance of RSV in the first 12 months of life and then RV in the following years [22]. Birth cohort studies and other epidemiological studies have shown a strong association between early RV-induced wheeze, and to a lesser extent, RSV-induced wheeze, and subsequent development of childhood asthma [23], [24], [25], [26]. Moreover, pediatric asthma attacks are mainly triggered by respiratory viruses, particularly RV, both in the preschool and school-age [10], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. The question of whether asthma-associated underlying inflammation promotes the pathogenic effect of viral infection or whether the virus induces exaggerated inflammation is still under debate and has been the subject of many research studies over the past 25 years.

Alongside viruses, there is also a growing interest on the impact of bacteria in the onset of asthma attacks and the perpetuation of inflammation. Neonatal airway colonization with bacteria including Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis and/or Streptococcus pneumoniae, has been associated with persistence of asthma [32]. Indeed, Kloepfer, et al. have shown frequent viral and bacterial co-infection in asthmatic children aged 2–18 years [33]. It is well known that viral infection can predispose to bacterial secondary infection. A few studies have begun to describe inflammatory phenotypes linked with altered microbiota, known as dysbiosis, within the airways [34], [35]. Interactions between viruses and bacteria, personal risk factors (e.g. genetic background and atopy), and environmental exposures may promote more severe acute asthma episodes that will influence the progression of asthma [21]. However, the precise role of each of these factors and their interplay with the host immune defenses remains to be elucidated.

The aim of this review was to synthesize studies exploring human innate immune mechanisms responses against viruses and bacteria during asthma attacks and to provide hypotheses to decipher how they may contribute to the phenotypes observed in childhood asthma. We will then discuss how therapeutic strategies targeting these pathways may improve the management of acute asthma in children.

2. Impact of viruses on the onset of asthma attacks: chicken or egg?

Up to now, mechanisms explaining susceptibility to develop acute asthma upon respiratory viruses, in particular RV and to a lesser extend RSV, in asthmatic children prone to exacerbation are not fully understood. As innate immune cells play a central role in the onset of anti-viral defenses, they have been the focus of many studies in pediatric and adult asthma, conducted both ex-vivo and in-vivo, contributing to the identification of new asthma endotypes. The original studies presented in this review have been summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Major studies (pediatric and adult population) assessing immune responses to viral infection during asthma exacerbation.

| Compartment | Study | Design and age-group | Main results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRR | In vitro and ex-vivo | |||

| AEC | Edwards M, et al. 2013[45] | RV-A16 Children:Severe therapy resistant asthma (STRA) 11y (9-15y) vs healthy controls | In STRA: lower basal levels of TLR3, reduced RIG-I, MDA5 levels after RV stimulation; lower basal levels of TLR3, reduced RIG-I, MDA5 levels after RV stimulation No association with age, IgE levels, allergen reactivity, BAL/sputum neutrophils and eosinophils, lung function | |

| AEC | Parsons KS, et al. 2014[46] | RV-B1 Adults:asthma/Healthy controls | In asthma: no impairment of expression of MDA5, TLR3 and reduced release of CXCL-10 | |

| AEC | Contoli M, et al. 2015[59] | RV-A16 Pre-treatment with IL-4 and IL-13 prior to infection Adults:atopic rhinitis/non-atopic healthy | In atopic cells: impaired immune response to RV-16 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-13, through inhibition of TLR3 expression and signaling (IRF3) | |

| AEC | Moskwa S, et al. 2018[61] | PIV-3/RV-B1 Adults:atopic asthma/non-atopic asthma/healthy controls | Atopic asthma: After PIV3 infection: higher IFN-λ1, IFN- α, IFN- β and IRF7 expressions After RV1B infection: IFN- β higher than in non-atopic asthmatics | |

| AM | Rupani H, et al. 2016[47] | RV-A16 Pre-treatment with Imiquimod (TLR7 agonist) Adults:severe asthma/Healthy controls | In severe asthma: reduced TLR7 expression, inverse correlation with number of exacerbations Increased levels of 3 microRNAs (miR-150, miR-152, and miR-375) Restored TLR7 expression after blocking these microRNAs with anti-miRNA oligonucleotides | |

| BAL cells PBMC | Sykes A, et al. 2012[48] | RV-A16 Adults:mild-to-moderate allergic asthma vs healthy controls | In asthma: no impairment of expression of PRR (TLR, RNA-helicases), their adaptor proteins, transcription factors downstream | |

| In vivo | ||||

| Sputum Serum PBMC | Deschildre A, et al. 2017[49] | School-age children 8.9 y (6-16y)Atopic asthma: virus vs no virus Severe exacerbation (64% virus, 51% RV)/steady state (8 weeks later) (25% virus, 11% RV) 24% virus at both time | Virus at exacerbation: similar TLR3, RIGI-I and MDA-5 expression on blood monocytes and DC, similar levels of IFN-β, IFN-γ, IFN-λ1 in sputum and plasma, higher airway IL-5 and eosinophils counts than patients with negative viral PCR Virus at both time: modification in PRR expression/function on PBMC, higher airway neutrophilic inflammation at steady state | |

| Bronchial biopsies | Zhu J, et al. 2019[67] | In vivo inoculation - RV-A16 Young adults:atopic asthma (23 y ± 1.4) vs non-atopic control subjects (27 y ± 2.3) | In asthma: PRR expression (TLR3, MDA5, RIG-I) not deficient at baseline; and induced after RV both in epithelium and sub-epithelium | |

| Type I and type III IFN | In vitro | |||

| AEC | Wark PA, et al. 2005[60] | RV-A16 Adults:Asthma vs healthy controls | In asthma: Impaired IFN-β, late virus release and late cell lysis, impaired apoptotic response | |

| AEC | Edwards M, et al. 2013[45] | RV-A16 Children:Severe therapy resistant asthma (STRA) 11y (9-15y), vs healthy controls | In STRA: IFN-β, IFN-λ1, IFN-λ2/3 mRNA levels lower and RV virus load higher No association with age, IgE levels, allergen reactivity, BAL/sputum neutrophils and eosinophils, lung function | |

| AEC | Gielen V, et al. 2015[57] | RV-B1/RV-A16 Pre-treatment with IL-4/IL-13 Children:STRA 11y (9-15y), vs healthy controls | In STRA: SOCS1 expression increased and related to IFN deficiency, increased viral replication Suppression of RV-induced IFN promoter activation in AEC by SOCS1, dependent on nuclear translocation | |

| AEC | Parsons KS, et al. 2014[46] | RV-B1 Adults:asthma/Healthy controls | In asthma: reduced release of IL-6, CXCL-8 and IFN-λ in response to RV, reduced release of CXCL-10 | |

| AEC | Kicic A, et al. 2016[58] | RV-B1/RV-B14 Children:Asthma 8.2 y (2.6–14.8) vs healthy children 8.4 y (3.2–15.6) | In asthma: greater virus proliferation and release, reduced apoptosis and wound repair (RV-B1), lower IFN-β, higher inflammatory cytokine production Addition of IFN-β: restored apoptosis, suppressed virus replication and improved repair of AEC from asthmatics, no effect on inflammatory cytokine production | |

| AM | Rupani H, et al. 2016[47] | RV-A16 Pre-treatment with Imiquimod (TLR7) Adults:severe asthma/Healthy controls | In severe asthma: reduced IFN responses Increased levels of 3 microRNAs (miR-150, miR-152, and miR-375): Blocking these microRNAs with anti-miRNA oligonucleotides increased IFN production | |

| BAL cells | Sykes A, et al. 2012[48] | RV-A16 Adults:mild-to-moderate allergic asthma vs healthy | In asthma: induction of type I IFN delayed and deficient, associated with airway hyperresponsiveness | |

| Bronchial biopsy specimens | Baraldo S, et al. 2012[56] | RV-A16 Children, 5y ± 0.5: asthma, atopy/Asthma, no atopy/Atopy, no asthma/No atopy nor asthma (Controls) | In all groups vs controls: reduced type I and III IFN production, increased RV viral RNA IFN inversely correlated with airway eosinophils, IL-4, epithelial damage, total IgE (type III IFN) | |

| Whole blood cultures | Bufe A, et al. 2002[62] | NDV Children:Allergic asthma/non-allergic asthma/allergic rhinitis/healthy control | In allergic asthma: lower virus-induced IFN-α in allergic asthma/ rhinitis: higher production of IFN-γ | |

| PBMC | Gehlhar K, et al. 2006[63] | RSV-1A/NDV Adults:Allergic asthma vs healthy controls | In allergic asthma: significant reduction of virus-induced IFN-α release, independent of virus used; no influence of medication (cortico-steroids) | |

| PBMC | Iikura K, et al. 2011[64] | RV-B14Wheeze/healthy; Young children: 2-6y; Youth group: 7–19 y; Adult group: ≥ 20y | Asthma (youth group): lower IFN-α production Asthma (youth group and adults): lower IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10 and sFasL productions Wheeze (young children): lower IL-10 associated with persistent wheeze at 2 y follow-up | |

| PBMC | Sykes A, et al. 2012[48] | RV-A16 Adults:mild-to-moderate allergic asthma vs healthy controls | In asthma: no impairement of type I IFN in PBMC, as opposed to BAL cells | |

| PBMC | Durrani S, et al. 2012[65] | RV-A16 Children 10–12 y:allergic asthma/non-allergic asthma/airborne sensitization without asthma/healthy controls. | Allergic asthma: lower IFN-responses after cross-linking FcεRI (vs sensitization and vs controls); higher surface expression of FcεRI on pDC and mDC Inverse relationship between total IgE and diminished IFN secretion, only when cross-linking of FcεRI | |

| PBMC | Simpson J, et al. 2016[66] | RV-B1 Adults:asthma, 76% atopic. Sputum phenotypes: eosinophilic/neutrophilic/paucigranulocytic/granulocytic | In neutrophilic asthma: significantly less IFN-α than PBMC from eosinophilic and paucigranulocytic asthma after RV; IFN-α inversely correlated with serum IL-6, sputum IL-1β Sputum neutrophils and dose of inhaled corticosteroids independent predictors of reduced IFN-α | |

| Type I and type III IFN | In vivo | |||

| Bronchial biopsies | Zhu J, et al. 2019[67] | In vivo inoculation - RV-A16 Young adults: atopic asthma (23 y ± 1.4) vs non-atopic control subjects (27 y ± 2.3) | In asthma: IFNα/β deficiency in epithelium, at baseline, day 4 and week 6 post-inoculation; correlated with viral load, and clinical severity Sub-epithelium: lower frequencies of monocytes/macrophages expressing IFNα/β after RV infection in sub-epithelium; subepithelial neutrophils were the source of IFNα/β | |

| BAL monocytes and AM | Contoli M, et al. 2006[71] | In vivo inoculation - RV-A16 Adults:severe asthma (ex vivo)/mild asthma without steroids treatment (ex vivo and in vivo) vs healthy controls | In asthma/Ex vivo: Impaired induction and production of type III IFN-λ1 and IFN-λ2/3 in AEC and AM, impaired induction of IFN- λ upon LPS stimulation In asthma/in vivo: severity of symptoms, BAL virus load, airway inflammation, reduction of lung function inversely correlated with ex vivo production of IFN-λ | |

| Nasal washes | Miller EK, et al. 2012[70] | Natural infection: 82% virus Children 5–18 y Upper respiratory infection; Wheezing/no-wheezing RV in 56% wheezing/37% non-wheezing | Specific association between RV infection and asthma exacerbation, but no difference in virus titers, RV species and inflammatory or allergic molecules between RV + wheezing and non-wheezing children In RV + wheezing children: IFN-λ1 level higher, increased with worsening symptoms | |

| Nasal washes | Kennedy J, et al. 2014[29] | Natural infection: 74 children (4–18 y):acute wheezing (57% RV)/acute rhinitis (56% RV)/controls Inoculation (RVA-16): 24 young adults Asthma/healthy | Natural infection: No difference in viral loads and levels of IFN-λ1 between wheezing and acute rhinitis; In children with wheezing: lower levels of sICAM-1 Inoculation: No difference in viral load between groups, levels of sICAM-1 correlated with RV levels | |

| Nasal washes Induced sputum | Schwantes E, et al. 2014[68] | Natural infection Adults:asthma vs healhy 17 exacerbations : 67% RV | In asthma, at exacerbation: sputum RNA levels of IFN-α1, IFN-β1 and IFN-γ correlated with exacerbation and the peak Asthma Index, early in the course of infection, higher levels of IL-13, IL-10 | |

| Serum PBMC | Bergauer A, et al. 2017[30] | Ex vivo inoculation of RV-1B on PBMC cultures In vivo natural infection Preschool children 4-6yAsthma at baseline (54% RV)/Asthma at exacerbation (100% RV) vs healthy controls | Ex vivo: induction of STAT1/STAT2 by RV in asthma/IRF9 in controls/IRF1 in both Natural infection (baseline): No increase of IFN-α expression in RV + asthma patients compared with RV + healthy controls; increase of IFN-λ protein with RV, both in asthma patients and controls Natural infection (exacerbation): reduced serum IFN-α at exacerbation compared with RV healthy children at baseline | |

| Sputum Serum PBMC | Deschildre A, et al. 2017[49] | School-age children 8.9 y (6-16y)Atopic asthma: virus vs no virus Severe exacerbation (64% virus, 51% RV)/steady state (8 weeks later) (25% virus, 11% RV)/24% virus at both time | Virus at exacerbation: similar levels of IFN-β, IFN-γ, IFN-λ1 in sputum and plasma, higher airway IL-5 and eosinophils Virus at both time: lower levels of IFN-γ in plasma and sputum at exacerbation, higher airway neutrophilic inflammation at steady state | |

| Sputum Plasma | Lejeune S, et al. 2020[8] | Preschool children 30 mo (1y-5y)Recurrent wheeze/preschool asthma; 47% atopy; 70% prone to exacerbation (≥2 exacerbations in the previous year) Severe exacerbation (94% virus, 73% RV)/steady state (8 weeks later) (67% virus, 50% RV) | Children prone to exacerbation: lower plasma concentrations of IFN-β and CXCL10 at exacerbation, and lower plasma levels of CXCL10 at steady state | |

| Alarmins and cytokines | In vitro | |||

| Co-culture AEC and T cells | Qin L, et al. 2011[83] | RSV-A2 AEC T cells extracted from adult PBMC (healthy volunteers) | Prolonged RSV infection in AEC induced T cells differentiation in Th2 and Th17 subsets that released IL-4, IFN-γ and IL-17 induced by supernatants from RSV-infected AEC | |

| AEC | Lee HC, et al. 2012[79] | RSV-A AEC from healthy children and asthmatic children | Production of TSLP after infection of AEC with RSV, via activation of an innate signaling pathway that involved retinoic acid induced gene I, interferon promoter-stimulating factor 1, and nuclear factor-κB. Greater levels of TSLP after RSV infection in AEC from asthmatic children than from healthy children | |

| PBMC | Jurak L, et al. 2018[82] | RV-A16 and IL-33 co-exposition Adults with allergic asthma vs healthy controls | In asthmatic cells: IL-5 and IL-13 release induced by RV, enhanced by IL-33, surface protein expression of ST2 induced by IL-33 Predominant source of IL-13 release: ILC2 In healthy cells: IL-33 had no effect on IL-5 and IL-13 production | |

| In vivo | ||||

| BAL PBMC | Jackson D, et al. 2014[81] | In vivo inoculation Ex vivo study: AEC, PBMC (T cells, ILC2) Adults:mild-to-moderate asthma vs non-atopic healthy volunteers | In vivo: IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 induced by RV in BAL in asthma Type 2 cytokines and IL-33 corelate with clinical outcomes and viral load Ex vivo: IL-5 and IL-13 production directly induced by IL-33 present in RV-infected AEC supernatants by human ILC2 and T cells | |

| PBMC Serum Nasal washes | Haag P, et al. 2018[80] | Preschool children 4-6y Ex vivo study: RVB-1 inoculation In vivo:asthma (54% RV)/controls (45% RV) at baseline | Ex vivo: Induction of ILC2 genes in asthma following RV inoculation In vivo: Down regulatation of sST2 in asthma and controls by RV Up regulation of sST2 in RV- asthma patients with low levels of 25(OH)-VitD3 In asthma: direct correlation of serum sST2 with nasal IL-33 | |

| Nasopharyngeal aspirates | Yuan XH, et al. 2020[78] | Children aged less than 14yBronchiolitis or pneumonia 19.7% RV, 35 bronchiolitis and 31 pneumonia cases | RV bronchiolitis: increased IL-4/IFN-γ and decreased TNF-α/IL-10 ratios, compared with RV pneumonia | |

| Sputum Plasma | Lejeune S, et al. 2020[8] | Preschool children 30mo (1y-5y)Recurrent wheeze/preschool asthma; 47% atopy; 70% prone to exacerbation (≥2 exacerbations in the previous year) Severe exacerbation (94% virus, 73% RV)/steady state (8 weeks later) (67% virus, 50% RV) | Children prone to exacerbation: lower plasma concentrations of IFN-γ, IL-5, TNF-α, IL-10, and lower levels of IFN-γ in sputum at exacerbation At steady state, lower plasma levels of IFN-γ | |

Studies conducted in animal models, and/or without administration of viral particles (e.g. administration of TLR agonists, double-stranded RNAs) were not included in this table.

AEC: Airway epithelial cells; AM: Alveolar macrophages; BAL: broncho-alveolar lavage; CCL: C–C motif ligand; CXCL: C-X-C motif ligand; FcεRI: high-affinity IgE receptor; IgE: Immunoglobulin E; IFN: Interferon; IL: Interleukin; ILC2: type 2 innate lymphoid cells; IRF: interferon regulatory factor; mDC: myeloid dendritic cells; LPS: Lipopolysaccharides ; MDA-5: melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5; NDV: Newcastle disease virus; PBMC: peripheral blood mononuclear cells; pDC: plasmacytoid dendritic cells; PBMC: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; PIV3: parainfluenza virus type 3; PRR: pattern recognition receptor; RIGI-I: retinoic-acid inducible gene I; RSV: Respiratory syncytial virus; RV: Rhinovirus; sFasL: Serum Soluble Fas Ligand; sICAM-1: Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1; siRNA: small interfering RNA; SOCS1: Suppressor Of Cytokine Signaling 1; sST2: soluble suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (IL-33 receptor IL1RL1); STAT: signal transducer and activator of transcription; STRA: severe therapy resistant asthma; Th2: T helper 2; TLR: Toll like receptor; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor.

2.1. Virus recognition during asthma attack is mainly driven by airway epithelial cells

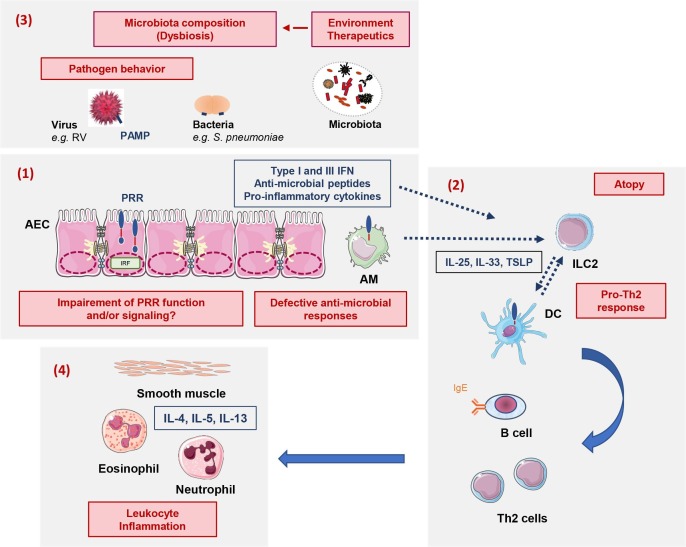

Before addressing the viral infections impact on asthma attacks, we will briefly describe the virus-induced anti-viral responses. Airway epithelial cells (AEC) are the main cellular targets of pathogens, and act as sentinel cells in response to infection ( Fig. 1 ) [36], [37], [38]. These structural cells are a central part of innate immune response [39]. They first act as a complex physicochemical barrier, via the presence of tight intercellular junctions and the muco-ciliary escalator, clearing foreign particles out. If not cleared, Pathogen Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMP) on the surface of infectious agents, will then be recognized through Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRR), in particular Toll-Like Receptors (TLR) and intracellular RNA helicases, which will trigger innate immune responses. Although AEC play an early and central role in orchestrating innate immune defenses, innate immune cells including alveolar macrophages (AM) and dendritic cells (DC), especially plasmacytoid DC (pDC), are also involved in innate immune responses against pathogens [40], [41], [42], [43], [44].

Fig. 1.

Summary of the main mechanisms favoring asthma development and involved in asthma attack. These mechanisms (in red) involve: (1) Impairment of innate immune responses; (2) Influence of the host-microbiota dialog on Th2 inflammation; (3) Pathogen characteristics; (4) Airway leukocyte inflammation. These dynamic interactions may impact the presentations of asthma attacks, and have long-term consequences. AM: Alveolar macrophages; AEC: airway epithelial cells; DC: dendritic cells; IFN: Interferon; IL: Interleukin; ILC2: type 2 innate lymphoid cells; IRF: interferon regulatory factor; PAMP: Pathogen-associated molecular pattern; PRR: pattern recognition receptor; RV: Rhinovirus; TSLP: Thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

Studies aiming to explore PRR recognition by epithelial cells and innate immune cells from asthmatic children are multiple but heterogeneous. In cultures of primary AEC from children with severe therapy resistant asthma (STRA), lower expression levels of extracellular and intracellular PRR than healthy controls were observed at baseline [45]. Expression of PRR was also decreased upon infection with RV on these cultures and in those from adult asthmatics, suggesting a persistent defect in adulthood [45], [46]. Hence, in AM from adults with severe asthma, Rupani, et al. also showed a reduction of TLR7 expression after RV infection compared with healthy subjects, with an effect potentially mediated by microRNAs [47]. Conversely, in ex vivo cultures of cells from broncho-alveolar lavages (BAL) cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from adults with mild-to-moderate asthma, no impairment of PRR expression (TLR, RNA-helicases) was observed [48]. This discrepancy was also illustrated by our in vivo real-life study conducted in 72 school-age children with allergic asthma hospitalized for severe exacerbation, associated with viral infection in 64% (RV: 51%) [49]. Whereas viral infection did not modulate PRR expression and function on PBMC as compared with non-infected asthmatic patients, a reduced expression of PRR was reported in a sub-group of children prone to reinfection outside an exacerbation (steady state 8 weeks later), and displaying neutrophilic airway inflammation away from exacerbation [10], [49]. Although present both at exacerbation and steady state, this impairment of PRR expression as well as the inflammatory profile was not associated with the clinical evolution and risk of exacerbations in the year following exacerbation [50].

Altogether, these data suggest that impairment of PRR recognition in asthmatic children could be limited to a subpopulation of patients, potentially severe, and may persist into adulthood. Rather than an altered baseline expression or synthesis of PRR, a down-regulation of the expression and activation of the co-receptors, and/or enzymes involved in signaling may be determinant. Longitudinal in vivo studies could provide more insights into these mechanisms and allow studying their dynamics during the course of the disease.

2.2. Modulation of anti-viral responses

Activation of PRR on AEC and innate immune cells will onset various signaling pathways, such as interferon regulatory factors (IRF) 3 and 7, and nuclear factor-kappa B pathway (NF-kB). This will lead to the production of anti-viral molecules such as interferons (IFN) and anti-microbial peptides, including interferon-stimulated genes (ISG) as well as cathelicidins and defensins [51]. Anti-microbial peptides have immunomodulatory activities and can alter host cellular responses. LL-37, also called human cationic antimicrobial peptide is the only human peptide of the cathelicidin family and one of the most-studied [52], [53]. In in vitro models, LL-37 has the ability to reduce virus replication, notably for RSV [53], [54]. In a population of 77 asthmatic children, Arikoglu, et al. have shown that children prone to develop acute asthma attacks displayed higher blood levels of cathelicidins and lower levels of vitamin D at baseline than children with controlled asthma, suggesting a role for anti-microbial peptides in acute asthma [55]. However, the evolution of these baseline levels during acute asthma attacks and their impact on the anti-viral and inflammatory response remain unknown.

The majority of studies conducted in asthmatic subjects have had the aim to explore anti-viral IFN response upon viral infection. They have observed a defect of production of type I IFN. In response to RV, most ex-vivo studies have demonstrated an impairment of IFN-α and IFN-β production in AEC from pediatric asthmatic patients compared to levels observed in cells from healthy controls [45], [56], [57], [58]. This impairment was also demonstrated in adult cells [59], [60], [61]. Interestingly, similar results have been observed in ex-vivo cultures of PBMC. As early as 2002, Bufe, et al. have shown in an ex-vivo model a defective production of IFN-α in PBMC from pediatric asthmatic patients compared to healthy controls, upon Newcastle disease virus (NDV) infection, an avian respiratory virus belonging to the Paramyxoviridae family and well-known potent inductor of IFN-α [62]. They later extended these observations in whole blood cells cultures from adult asthmatics, upon infection with either NDV of RSV [63]. In the later years, similar results have been shown in pediatric studies [64], [65] but also in adult studies [45], [48], [66]. So far, only a few studies have been conducted upon in vivo inoculation and natural infection. In a cohort of preschool children, IFN-α systemic levels were reduced at the time of RV-induced exacerbation in asthmatics, as compared with healthy controls during an asymptomatic RV infection [30]. In our recently published cohort of preschool asthmatic children with natural virus-induced exacerbation (RV: 73%), the most severe children, who were prone-to-exacerbation, displayed lower plasma concentrations of IFN-β at exacerbation than the others, suggesting a defect of production in response to viruses limited to this sub-population [8]. In another study conducted in older children, we did not observe altered IFN responses in sputum, plasma and cultures of stimulated-PBMC of patients presenting a virus-induced exacerbation, compared with those with a non-virus-induced exacerbation [49]. In adult asthmatics, a significant type I IFN defect was demonstrated in bronchial epithelium and sub-epithelium obtained from bronchial biopsies compared with healthy controls, after experimental infection with RV-A16 [67]. In contrast, Schwantes, et al. described elevated rather than low RNA levels of type I IFN in sputum from adult asthmatic patients, compared to those observed in healthy subjects, early in the course of a virus-induced exacerbation.[68].

Following their discovery in 2003, there has been increasing knowledge regarding the implication of type III IFN implication in anti-viral responses [69]. Ex-vivo studies conducted in AEC from asthmatic subjects have suggested a parallel impairment of IFN-λ1 and IFN-λ2/3 production upon RV infection in pediatric patients [45], [56], [57], and this impairment seemed to persist in adult patients [46], [59]. In vivo, this defective response was not observed at the time of asthma exacerbation in sputum and/or PBMC from atopic asthmatic children [30], [49], [70], nor in adults [68], [71], suggesting that there are compensatory mechanisms or other sources of IFN, supplementing the defect observed in resident cells.

A few studies have explored the potential pathways leading to a defect of IFN production in asthmatic patients. Downregulation of IRF3 or IRF7, following virus infection in asthmatic cells, has been suggested [57], [59]. Gielen, et al. have also demonstrated a role of the molecule suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1), exercising a negative-feedback on IFN production following viral infection in children with STRA [57].

Collectively, these studies suggest a potential impairment of anti-viral IFN response, in particular type I IFN, during asthma attack. Rather than explained by immaturity in the first years of life, this defective response could also be limited to a sub-phenotype of patients who are prone-to-exacerbation, from early childhood to adulthood. The effect of age, the kinetics of the IFN response following viral infection and the impact of viral load in the airways remain to be addressed.

2.3. Cytokines and epithelial-derived alarmins (IL-25, IL-33 and TSLP) response against viral infection

Airway epithelial cells display immunoregulatory properties by producing pro-inflammatory cytokines, including alarmins interleukin (IL)-25, IL-33 and thymic stromal lymphopeietin (TSLP), released upon viral infection, and implicated in the recruitment of macrophages, DC, T cells and granulocytes, such as eosinophils and neutrophils. This will promote the adaptive immune response through DC maturation and migration to draining lymph nodes associated with the airways. Dendritic cells will thus induce naïve T cell differentiation into antigen-specific T cells. This will drive the adaptive immune response within the airways to clear the virus out. The alarmins also contribute to a biased T helper (Th)2 immune response by activating type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) and polarizing DC in order to promote T cells differentiation (Fig. 1). This specific cytokine environment in asthmatic patients favor naïve T cells polarization into Th2 cells, producing IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, as opposed to Th1 cells, producing IFN-γ and TNF-β [37], [72]. These cytokines are responsible for the type 2 inflammation and induce the pathophysiological features of asthma, including eosinophil mobilization, mucus hypersecretion, smooth muscle hyperplasia and airflow obstruction [3], [73]. Under the influence of IL-5, eosinophils will enter the airways and perpetuate type 2 inflammation [49], [74]. They will also contribute to resolution of immune responses, including tissue repair [75]. Other cytokines, such as type 17 cytokines: IL-17, IL-21, IL-22, can also promote mucus hypersecretion and production of cytokines and chemokines by AEC. They will favor the recruitment of neutrophils, through the induction of C-X-C chemokines, conducting to a state of chronic inflammation [67]. In the longer term, IL-17 may contribute to the development of airway remodeling during asthma by enhancing the production of profibrotic cytokines, proangiogenic factors, proteases and collagen [76], [77].

In children, the influence of respiratory viruses and innate immune mechanisms on the adaptive immune response development may be crucial. First, some respiratory viruses may induce the release of alarmins, and thus favor the development of Th2 inflammation. A recently published study showed that children with RV-positive-bronchiolitis displayed increased IL-4/IFN-γ ratio in nasopharyngeal aspirates [78]. Upon RSV infection, Lee, et al. observed a higher production of TSLP by AEC from asthmatic children compared to healthy controls [79]. Hence, some respiratory viruses may induce Th2 inflammation in the airways of children and this may be increased in an asthmatic environment. In a cohort of preschool asthmatic children, ILC markers, such as soluble ST2, were induced in vivo following RV infection in preschool asthmatic children, and were correlated with nasal levels of IL-33 [80]. In our study of school-age children, at exacerbation, airway inflammation in infected patients was characterized by significantly higher IL-5 concentration and eosinophil count than in non-infected patients [49]. This may not be specific to childhood, as Jackson, et al. have also demonstrated an induction of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 in BAL following RV inoculation in asthmatic subjects, associated with exacerbation severity [81]. Additional in vitro experiments showed that IL-33 directly induced Th2 cytokine production by T cells and ILC2. However, this RV-induced Th2 inflammation could be limited to an asthmatic environment in adults, as suggested by an in vitro study reproducing the induction of IL-4 and IL-13 by asthmatic PBMC after co-exposition with RV and IL-33, but showing no effect on PBMC from healthy donors [82]. In addition, exposure to respiratory viruses has also been associated with an increase in Th17 cytokines, as demonstrated in co-cultures of RSV-infected AEC with T cells [83].

Interferon production is also closely linked to Th2 and inflammatory cytokines. In asthmatic preschool children prone to exacerbation, we observed simultaneously lower production of Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ), Th2 cytokines (IL-5), pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α), regulatory cytokines (IL-10), and type 1 IFN (IFN-β) during virus-induced exacerbation in a subgroup of preschool children with characteristics of severe asthma and a history of frequent exacerbations [8]. This association seems to persist in adults, as suggested by Parsons, et al. reporting a parallel decrease of type III IFNs and of IL-6, (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL)8 and CXCL10 in adult asthmatic AEC inoculated with RV [46]. In a murine model of allergic asthma, IRF3 controlled the parallel evolution of IFN and Th2 cytokines during acute episodes induced by allergen exposure [84]. Some adult studies have suggested bi-directional influences during viral infection. Upon RV infection, pre-treatment with Th2 cytokines in cultures of AEC may impair TLR3 and IRF3 signaling pathway [59], or type 1 and 3 IFN expression [57]. Lower production of type I IFN, displayed by some children, could also reduce the apoptosis of neighbored-infected cells and increase viral loads, consequently amplifying airway inflammation, inflammatory cytokine production and thus, asthma attack severity [58], [60].

Altogether, these studies confirm close interactions between innate and adaptive immune mechanisms against viruses in an asthmatic environment. Modulating airway inflammation, particularly Th2 inflammation, could therefore directly improve anti-viral responses during asthma attacks in some children.

2.4. Viral behavior during asthma attack

Although the impairment of anti-viral responses plays a key role in asthma attack, characteristics of the microorganisms are also important. First, pathogenicity of RV strongly differs according to subtypes, probably because of the implication of different cellular targets. Indeed, infection with RV-C strains, which use cadherin-related family member 3 (CDHR3) as a receptor, may be associated with higher clinical severity [10], [31], [85], whereas B serotypes seem to be responsible for milder symptoms. Interestingly, single nucleotide polymorphism in the CDHR3 gene, which influences the efficiency of RV-C to infect its target cells, has been associated with childhood asthma susceptibility [86]. Moreover, different viral strains could have different replication rates and thus induce higher viral loads [87]. Rhinovirus C strains could also modulate the airways inflammation, and induce higher levels of Th2 and/or Th17 cytokines, as shown in preschool children with RV-C-induced wheeze [88]. Second, systemic viremia has been observed in children infected with respiratory viruses, such as RV-C, and young age was found to be a risk factor associated with viremia [89]. This state could induce an enhanced inflammation in children by interaction of viruses with systemic immune cells. Finally, viral-coinfection has been frequently observed at exacerbation in asthmatic children, particularly in the preschool years [30], [31]. The combined effects of several viruses within the airways may modulate both the innate and adaptive responses.

These data demonstrate that, in susceptible children, the nature of respiratory viruses, their spreading, as well as their interactions with the host cells may directly impact the inflammation and the severity of asthma exacerbations.

2.5. Emerging role of the airways virome

The role of viral carriage and/or asymptomatic infection at steady state, i.e. outside an exacerbation, in asthmatic patients has also been hypothesized. Hence, pediatric studies have shown a frequent virus shedding in children, with RV positive samples observed in 19–29% of unselected asthmatic children and in 15–23% of healthy children [10], [28], [90], [91]. In the previously-cited cohort of preschool children prone to exacerbation, we observed even higher rates, with 67% of positive PCR (51% for RV) at steady state [8]. In 78 school-age children, we also observed that 10% of children had positive RV sampling at exacerbation and steady state, and that RV serotypes were systematically different at both time points, pointing toward reinfection rather than persistence [10]. Consistent with these observations, Bergauer, et al. also found 54% of RV at steady state in preschool children with asthma, vs 45% in healthy controls [30]. Interestingly, RV carriage in both asthmatics and healthy controls was found to be associated with higher levels of type III IFN at baseline than in subjects without virus. This increase in baseline inflammation seems to persist in adulthood. Hence, in sputum cells from 57 asthmatic adults, da Silva, et al. have shown higher baseline levels of IFN and anti-viral molecules compared with healthy subjects [92]. In all, one could hypothesize that RV persistence in asthmatic patients could induce a pro-inflammatory state and/or a desensitization of PRR, which could reduce the response against pathogens within the airways upon new infection.

Alongside RV, other respiratory viruses, could also take part in these processes. Metagenomic analyses have made it possible to identify hundreds of viral species within the airways, constituting the respiratory tract virome [93]. In non-asthmatic children, Wang, et al. have shown multiple common epidemic respiratory viruses in children with severe acute respiratory infection, whereas, the virome was less diverse and mainly dominated by the Anelloviridae family in healthy children [94]. Anelloviruses are major components of the virome and display immunomodulatory properties on both innate and adaptive immunity [95]. Although their presence has been associated with an impaired lung function in asthmatic children [96], to our knowledge, no study has evaluated their association with asthma attacks. Thus, the contribution of these viruses and their interactions with both pathogenic infectious agents, as well as commensal bacteria from the pulmonary microbiota on chronic inflammation and the onset of acute asthma remain to be determined.

3. The emerging role of pathogenic bacteria and microbiota in asthma

Increasing evidence indicates that the respiratory microbiota, including bacterial and viral microorganisms has an important role in respiratory health and disease [97], [98]. In addition, recent data underline the role of bacterial infections in the development and progression of asthma, as summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Major human studies (pediatric and adult population) assessing the impact of pathogenic bacteria and microbiota during the development, the attack and the natural history of pediatric asthma.

| Compartment | Study | Design and age-group | Main results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma development | Hypopharynx | Bisgaard H, et al. 2007[32] | Hypopharyngeal samples were cultured from 321 neonates at 1 month of age | 21% of children were colonized with S. pneumoniae, M. catarrhalis, H. influenzae, or a combination of these organisms. Colonization with one or more of these organisms, but not colonization with S. aureus, was significantly associated with persistent wheeze. Neonates colonized in the hypopharyngeal region with one or a combination of these organisms, were at increased risk for recurrent wheeze and asthma early in life. |

| Gut microbiota |

Arrieta MC, et al. 2015 [100] |

319 children enrolled in the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) Study | Children at risk of asthma exhibited transient gut microbial dysbiosis during the first 100 days of life Relative abundance of the bacterial genera Lachnospira, Veillonella, Faecalibacterium, and Rothia was significantly decreased in children at risk of asthma. This reduction in bacterial taxa was accompanied by reduced levels of fecal acetate. Inoculation of germ-free mice with these four bacterial taxa ameliorated airway inflammation in their adult progeny. |

|

| Lung | Loewen K, et al. 2015[102] | 213, 661 mother–child dyads with a median follow-up time of 9.3 years from birth Maternal antibiotic use was determined from records of oral antibiotic prescriptions |

36.8% of children were exposed prenatally to antibiotics and 10.1% developed asthma. Prenatal antibiotic exposure was associated with an increased risk of asthma. Maternal antibiotic use during 9 months before pregnancy and 9 months postpartum were similarly associated with asthma. |

|

| Hoskin-Parr L, et al. 2013[103] | 4,952 children from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Child antibiotic use and asthma, eczema and hay fever symptoms were reported | Children reported to have taken antibiotics during infancy (0–2 yr) were more likely to have asthma. The risk increased with greater numbers of antibiotic courses. The number of courses was also associated with a higher risk of eczema and hay fever but not atopy. |

||

| Gut microbiota | Patrick DM, et al. 2020[104] | 2,644 children from the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) prospective birth cohort and among them, 917 were analyzed for fecal microbiota | Reduction in asthma incidence over the study period was associated with decreasing antibiotic use in the first year of life.Asthma diagnosis in childhood was associated with infant antibiotic use (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.15) , with a significant dose–response; α-diversity of the gut microbiota was associated with a 32% reduced risk of asthma at age 5 years. |

|

| Acute asthma | Nasopharynx | Mansbach JM, et al. 2016[106] | The MARC-35 prospective cohort study of 1,016 infants (age less than 1 year) hospitalized with bronchiolitis and followed for the development of recurrent wheezing | RSV infection was associated with high abundance of Firmicutes and Streptococcus and a low abundance of Proteobacteria and the genera Haemophilus and Moraxella. RV infection was associated with low Streptococcus and high Haemophilus and Moraxella. RSV/RV coinfections had intermediate abundances. |

| Nasopharynx | De Steenhuijsen Piters WA, et al. 2016[105] | 106 children less than 2 years of age with RSV infection/26 asymptomatic healthy control | 5 nasopharyngeal microbiota clusters were identified, characterized by high levels of either Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus, Corynebacterium, Moraxella, or Staphylococcus aureus. RSV hospitalization were positively associated with H. influenzae and Streptococcus RSV-induced expression of IFN-related genes is independent of the microbiota cluster |

|

| Nasopharynx | Kloepfer KM, et al. 2017[107] | 17 adult subjects collected nasal mucus samples on a weekly basis for 5 consecutive weeks | Asymptomatic RV infections were associated with a significant increase in the abundance of Dolosigranulum and Corynebacterium.RV infection preceded the increased odds of detection of Streptococcus and Moraxella by 1 week. | |

| Blood | Giuffrida LM, et al. 2017[108] | 14 asthmatic and 29 non-asthmatic adult patients with acute respiratory infection 10 healthy individuals |

Higher blood concentrations of CCL2 and CCL5 in infected asthmatic patients than in non-asthmatic patients. Both asthmatic and non-asthmatics with pneumonia or bronchitis had higher concentrations of blood cytokines. | |

| Pharynx | Kama Y, et al. 2020[109] | Pharyngeal samples of outpatients and/or in patients children with acute exacerbations of asthma (n = 111) (median age: 2.8/2.6, respectively) | The 3 major bacterial pathogens were Streptococcus pneumoniae (29.7%), Moraxella catarrhalis (11.7%), and Haemophilus influenzae (10.8%). Patients with S. pneumoniae colonization had significantly shorter wheezing episodes and reduced lung inflammation (including lower level of TNF-α) |

|

| Asthma natural history | Nasopharynx | Teo SM, et al. 2018[110] | 244 infants with acute respiratory tract illnesses (ARIs) followed through their first five years of life | Dominance with Moraxella, Haemophilus and Streptococcus cluster were positively associated with acute respiratory tract illness. This change frequently preceded the detection of viral pathogens and acute symptoms. These changes were associated with ensuing development of persistent wheeze in children developing early allergic sensitization |

| Nasal microbiota | Zhou Y, et al. 2019[113] | A 1 year longitudinal study in school-age children with mild-moderate persistent asthma treated with daily ICS (mean age 8.0 ± 1.8 years) | Children with nasal microbiota dominated by the commensal Corynebacterium / Dolosigranulum cluster at steady state experienced the lowest rates of exacerbation and disease progression. A switch towards the Moraxella- cluster was associated with highest risk of severe asthma exacerbation. |

|

| Lung | Mansbach JM, et al. 2020[111] | 842 infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis with a follow-up at 3 years | Increased abundance of Moraxella or Streptococcus species 3 weeks after day 1 of hospitalization was associated with an increased risk of recurrent wheezing. Increased Streptococcus species abundance the summer after hospitalization was also associated with a greater risk of recurrent wheezing |

|

| Oropharynx | Cuthbertson L, et al. 2019[112] | Oropharyngeal swabs were collected from 109 children hospitalized for acute wheezing/75 non-wheezing controls. | No significant difference in bacterial diversity between wheezers and healthy controls In wheezers, attendance at kindergarten or preschool was, associated with increased bacterial diversity.in contrast with rhinovirus (RV) infection |

|

| Nasopharynx | McCauley K. et al. 2019[35] | 312 school-age asthmatic patients enrolled in a trial of omalizumab, nasal secretion samples collected after randomization | Nasal microbiotas dominated by Moraxella species were associated with increased exacerbation risk and eosinophil activation. Staphylococcus or Corynebacterium species–dominated microbiotas were associated with reduced respiratory illness and exacerbation events. Streptococcus species–dominated microbiota increased the risk of RV. |

|

| Sputum | Abdel-Aziz MI. et al. 2020[114] | Sputum samples were collected in 100 severe asthmatics of the U-BIOPRED adult patients cohort at baseline and after 12–18 months of follow-up | Two microbiome-driven clusters were identified, characterized by asthma onset, smoking status, treatment, lung spirometry results, percentage of neutrophils and macrophages in sputum. Patients of the most severe cluster displayed a commensal-deficient bacterial profile which was associated with worse asthma outcomes. Longitudinal clusters revealed high relative stability after 12–18 months in the severe asthmatics. |

|

| Lung (BAL) | Robinson PFM, et al. 2019[34] |

Children: 35 wheezers categorized as MTW or EVW BAL obtained at steady state |

There was no relationship between lower airway inflammation or infection and clinical preschool wheeze phenotypes. 2 groups identified: 1) a Moraxella species dysbiotic microbiota cluster that associated with airway neutrophilia and a mixed microbiota; 2) a mixed microbiota cluster with a macrophage- and lymphocyte-predominant inflammatory profile |

|

BAL: Broncho-alveolar lavage; EVW: Episodic Viral Wheeze, MTW: Multiple trigger Wheeze, RSV: Respiratory syncytial virus; RV: Rhinovirus.

During the first weeks of life, the respiratory tract begins to develop a niche-specific community pattern, where Staphylococcus aureus and Corynebacterium replace the originally colonizing bacteria and become the dominant microorganisms [98]. The most dramatic changes occur during the first 2 months. In the following six months, the respiratory microbiota continues to mature; relative abundance of S. aureus declines, and an increase in Moraxella, Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Dolosigranulum, Alloiococcus, and Prevotella sp. is observed. This period is crucial and alterations of the microbiota have been implicated in the development and the manifestations of chronic lung diseases.

3.1. Bacteria and asthma development

Using bacterial culture techniques, it has been demonstrated that neonates born to asthmatic mothers with upper airway colonization with S. pneumoniae, M. catarrhalis, and/or H. influenzae were at higher risk of presenting asthma at the age of 5 years [32]. This was associated with an aberrant immune response, with increased IL-5 and IL-13 synthesis in PBMC obtained at the age of 6 months [99]. Interestingly, evaluation of the gut microbiota in infants included in the Canadian (CHILD) study showed that infants at risk of asthma exhibited transient alterations of the microbiota, known as dysbiosis, in neonates [100]. More specifically, the relative abundance of the commensal bacterial genera Lachnospira, Veillonella, Faecalibacterium, and Rothia was significantly decreased in children at risk of asthma. Furthermore, antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis has been shown to facilitate the development of allergic asthma in experimental murine models and clinical studies [101]. In a population-based cohort, it has been reported that pre- and post-natal antibiotic exposure was associated with a higher asthma risk [102]. No significant difference in bacterial diversity was observed between samples from those with wheeze and healthy controls. Age and attendance at day care or kindergarten were important factors in driving bacterial diversity whereas wheeze and viral infection were not found to be significantly associated to the bacterial communities. In the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) cohort, children for whom antibiotics course was reported before the age of 2 years were more likely to have asthma at age 7, although microbiota was not characterized [103]. Similarly, in British Columbia (Canada), “controlled” antibiotic use during infancy was associated with a reduction in the incidence of pediatric asthma, and was related with the preservation of gut microbial communities [104]. Altogether, these data confirm the need to preserve the microbiota in early infancy in order to limit the development of asthma.

3.2. Relationship between bacteria and asthma attack

Bacterial infections potentially contribute to the severity of symptomatic respiratory viral infections and asthma attacks in children. Indeed, there are bidirectional interactions between viruses and airway bacteria that appear to modulate the severity of illness and the likelihood of asthma attack [20]. Pediatric studies have shown that upper respiratory tract colonization with Streptococcus, Haemophilus, and/or Staphylococcus genus during RSV and RV infection increases the risk of hospitalization independently of age and of the presence of asthma [105], [106]. In our previously-cited cohort of preschool children, asthma attacks were frequently associated with viral infection (94%, mostly RV). Pathogenic bacteria were isolated in induced sputum in 56%, mainly H. influenza, M. catharralis or S. pneumoniae [21]. In adult asthmatics, asymptomatic RV infection was associated with increased abundance of Dolosigranulum and Corynebacterium, whereas symptomatic RV infection seemed to be related with a higher frequency of Moraxella [107]. In another adult study, co-infection with virus and bacteria induced higher levels of cytokine/chemokine than bacterial infection [108]. Interestingly, circulating CCL2 and CCL5 concentrations were increased in infected asthmatic patients compared with non-asthmatic patients. Streptococcus species may also influence the course of asthma exacerbation, as shown by Kama, et al. in preschool children [109]. Indeed, patients with S. pneumoniae colonization in the pharyngeal microbiota had significantly shorter wheezing episodes and reduced lung inflammation (including lower levels of TNF-α).

In summary, these data suggest an ability for bacteria to promote asthma attacks and modulate the inflammation during childhood. Targeting bacterial infections during asthma attacks could thus be an alternative strategy in some children.

3.3. Dysbiosis and impact on asthma natural history

Early-life dysbiosis of the microbiota, in particular lung microbiota, may have long-term consequences on asthma natural history. During viral infection in children less than two years old, detection of Moraxella was found to be associated with current wheeze at 5 years old and presence of Streptococcus, Moraxella, or Haemophilus was associated with a high risk of asthma development [110]. Mansbach, et al. showed in a joint modeling analysis adjusting for 16 covariates, including viral trigger, that a higher relative abundance of Moraxella or Streptococcus species 3 weeks after day 1 of hospitalization for severe bronchiolitis was associated with an increased risk of recurrent wheezing [111]. In contrast, no significant difference in microbiota composition was observed between oro-pharyngeal microbiota from children with acute wheezing (0–14 years old) and healthy controls [112]. In this study, the large range of patient ages and day care attendance were important confounding factors, since the microbiota evolves throughout childhood.

In school-age asthmatic children, Zhou, et al. assessed by longitudinal measurements the relationship between nasal airway microbiota and either loss of asthma control, or risk of severe exacerbations [113]. Whereas the commensal Corynebacterium/Dolosigranulum cluster characterized the patients with the lowest risk of disease progression, a switch towards the Moraxella cluster was associated with the highest risk of severe asthma exacerbations. Similarly, in another cohort of school-age asthmatic children, nasal microbiota dominated by Moraxella species was associated with increased exacerbation risk, and eosinophil activation at exacerbation [35]. Staphylococcus or Corynebacterium species–dominated microbiota were linked with reduced respiratory illness and exacerbation event rates, whereas Streptococcus species-dominated microbiota increased the risk of RV infection. Interestingly, using unbiased airway microbiome-driven clustering, Abdel-Aziz, et al. recently described in adult asthmatics two distinct robust severe asthma phenotypes that were associated with airway neutrophilia, and not related to the presence of Moraxella species [114]. Robinson, et al. assessed the lower airway microbiota by performing BAL at steady state in severe preschool wheezers [34]. They reported two profiles: a Moraxella species “dysbiotic” cluster, associated with airway neutrophilia and a “mixed microbiota” cluster associated with macrophage- and lymphocyte-predominant airway inflammation, thus suggesting that bacteria might influence the characteristics of lung inflammation.

Altogether, these data show that airway dysbiosis in early life might contribute to recurrent wheeze and asthma, and to the severity of the disease. Among bacterial species, the early presence of M. Catharralis and H. influenzae during childhood seems to be a marker of evolution toward a severe disease, through the modulation of the inflammatory reaction. In contrast, colonization with S. pneumoniae might have some anti-inflammatory effects. However, the role of bacteria is often exacerbated or modulated by intrinsic (atopy, inflammation characteristics) or extrinsic factors, such as viral infections and antibiotics.

4. Consequences on asthma phenotypes and endotypes

It is now clear that phenotyping and even more so, endotyping asthmatic patients is an essential step to understand the diversity of immune responses at the time of an asthma attack. We will review the commonly described endotypes of childhood asthma, successively based on airway leukocyte infiltrate, profiles of allergic sensitization and nature of asthma trajectories.

Among airway inflammatory phenotypes, neutrophilic asthma appears to be a distinct endotype, associated with asthma severity in adults, and possibly involved in corticosteroid insensitivity [76]. In children, several studies have shown that association of airway neutrophilia with severity is inconstant [115], [116], [117], [118], and may not persist throughout the course of the disease [116], [119]. However, neutrophils present in the airways of severe asthmatic children may have enhanced survival and proinflammatory functions that could increase baseline inflammation [120]. As previously stated, airway neutrophilia has also been associated with a different IFN response, at baseline and at the time of asthma attack, both in adults [66], [92] and pediatric studies [49]. This could have an impact on lung infections. Thus, we have shown that a subgroup of school-aged children with positive viral PCR both at baseline and exacerbation displayed airway neutrophilia [49]. In severe adult asthmatics, airway neutrophilia has also been associated with lesser microbiota diversity in BAL [114], [121]. Finally, experimental RV infection in adult asthmatic subjects directly induces bronchial mucosal neutrophilia [122]. Therefore, the neutrophilic endotype may be characterized by an alteration of airway microbiota and association with viral infections.

Airway eosinophilia is highly frequent in asthmatic children, observed in severe and non-severe asthma, often but not always associated with response to ICS, thus highlighting the diversity of eosinophilic profiles in pediatric asthma [116], [118], [123]. Mouse models and adult studies have suggested a role of IL-5 induced airway eosinophilia as a positive regulator of RV receptor intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 on AEC, and a negative regulator of PRR and antiviral responses [124], [125]. However, in children, it remains unclear whether airway eosinophils are involved in the pathophysiology of severe asthma, and in the propensity to develop acute asthma attacks [126]. In addition, peripheral blood eosinophilia, currently used as the basis for selection of eosinophil-targeted biologics, may not be representative of airway eosinophilia in children [127]. Most importantly, it has been reported that eosinophilia is not necessarily associated with higher levels of Th2 cytokines [118], and other cells such as alarmin-stimulated ILC2 may have a greater biological importance in the pathophysiology of asthma attacks [128]. Eosinophils can also have beneficial effects in childhood asthma, as they display regulatory functions and contribute to lung repair and mucosal homeostasis [75]. Peripheral blood eosinophilia has recently been identified has a biomarker predicting the decrease of severity throughout the adolescent years [16]. Finally, it remains to be determined whether eosinophil-targeted biologics, such as anti-IL-5 mepolizumab, are efficient in reducing asthma attacks in children [129]. Overall, as opposed to adults, airway eosinophilia does not appear as the preferential biomarker to classify pediatric patients nor to assess their risk of acute asthma attacks.

Rather than through the recruitment of eosinophils, type 2 inflammation may play a key role in some children’s susceptibility to develop acute asthma attacks through IgE sensitization. Hence, atopy, defined as allergic sensitization, is a key feature associated with risk of asthma attacks in childhood [7], [8], [14]. As shown by latent-class analyses, atopy is also one of the main factors that may account for the heterogeneity of the disease, especially in the preschool years [130], [131] and could drive response to treatment [3]. Pre-existing atopy may play a role in the modulation of IFN response upon viral infection in children, although studies have shown conflicting results [59], [61], [65]. Durrani, et al. have suggested a direct implication of the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) in this defect, as its cross-linking on pDC from asthmatic allergic patients is associated with reduced IFN secretion upon RV infection [65]. Following virus-induced exacerbation in atopic children, upregulation of FcεRI receptor on monocytes and DC was observed, associated with a concomitant upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-13 [132], suggesting that respiratory viral infection in atopic children may initiate an atopy-dependent cascade that amplifies virus-induced airway inflammation. This could initiate long-term remodeling and inflammation. Hence, IgE sensitization, especially if occurring early in life and multiple, has been identified as the main factor associated with long-term asthma risk (recurrence of exacerbations, persistence of asthma, impaired lung function) in neonatal cohorts, including MAAS (Great Britain), MAS (Germany), PARIS (France) and PASTURE (Europe) [133], [134], [135], [136].

Describing asthma trajectories in neonatal longitudinal cohorts may precisely allow identifying novel endotypes. For instance, in a birth cohort of children at high risk of atopy, cord blood cells were tested for their ability to produce IFN after exposure to polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (Poly I:C), a double stranded RNA that mimics viral PAMP [137]. A group of low producers of type I and III IFN response upon stimulation representing 24% of the patients was identified. They displayed higher risk of lower respiratory tract infection and persistent wheeze at the age of 5, suggesting that these clinical outcomes are partly determined by constitutional mechanisms.

Altogether, beyond airway leukocyte and type 2 inflammation, childhood asthma endotypes seem to be associated with the characteristics of airway microbiota and of the associated immune response. Because these might involve dynamic processes, the study of asthma trajectories throughout childhood is crucial. A better characterization of asthma endotypes will be an essential step in order to achieve a personalized medicine.

5. In the future: machine learning and systemic biological approaches

Digital tools provide an innovative way to study the integrated immune response in asthmatic patients. For instance, Custovic, et al. used machine learning in an in vitro model of RV-A16 infection on PBMC extracted from 11 years old children and described 6 clusters of cytokine response to infection [138]. One cluster, with patients from whom PBMC displayed low IFN responses, high pro-inflammatory cytokines, low Th2 responses and moderate regulatory responses, was associated with early-onset asthma and the highest risk of asthma exacerbations and hospitalizations for lower respiratory tract infection.

Omic technologies, known as genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, single-cell omics, metabolomics, microbiomics, exposomics, are others fast-developing tools, generating a massive amount of data reflecting the biological state of cell populations at a given time, that will certainly make possible in the future to identify new endotypes and their biomarkers [139], [140]. For instance, with the development of the Human Genome Project, genome-wide association studies have allowed to link childhood asthma with association signals in or near genes involved in innate immune response pathways, such as the TLR1 locus, and the IL-33 locus [141], [142]. Transcriptomics analyses, which aim at investigating all RNA transcripts in a biological sample, will certainly enable the identification of a large quantity of genes modulated in certain conditions. A recent study has described 94 distinct gene-expression modules between virus-induced and non-virus-induced exacerbation in nasal and sputum cells from a large cohort of school-age children [143]. In asthma attacks, this tool may also provide information on the activated pathways linked with inflammatory and anti-microbial response [144], [145]. RNA sequencing in nasal lavage cells from asthmatic children at exacerbation led to identify some genes overexpressed as relevant “nodes” linking genes of the inflammatory response, such as IRF7 [144]. Transcriptomic analyses have also been used to identify genes associated with different phenotypes of asthmatic patients [146]. Finally, metabolomics, the study of the metabolites produced in living systems (both humans and microbiota) represents another promising strategy in the upcoming years to address the role of immuno-metabolism as well as lung and gut microbiota in asthma pathophysiology [147], [148].

To sum up, systemic approaches integrating all biologic pathways are now increasingly used to study the mechanisms leading to susceptibility to acute asthma attacks in children. They may facilitate the identification of novel multimodal biomarkers linked with specific endotypes and therapeutic targets.

6. Therapeutic strategies modulating innate immune defenses during asthma attacks

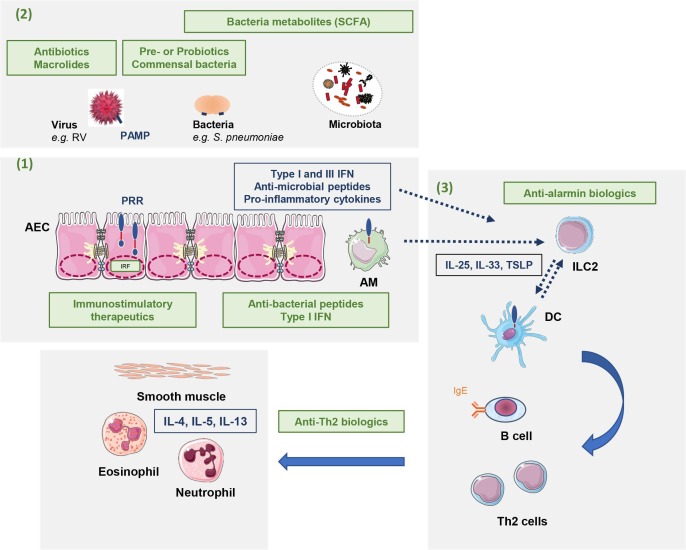

Conventional maintenance treatment, such as ICS, may be insufficient to prevent attacks in children, especially in severe asthma. Severe therapy-resistant asthma is precisely characterized by repeated severe exacerbations despite high dose daily treatment. As the knowledge about infection-underlying pathophysiological processes grows, new therapeutic approaches that may contribute to either improve innate immune responses or limit the occurrence and consequences of infections during asthma attacks have been recently explored (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Possible therapeutics strategies to limit asthma development/progression and attacks. These strategies (in green) target: (1) Enhancement of the innate immune responses; (2) Anti-infectious therapeutics and strategies to modulate the microbiota; (3) Alarmins and anti-Th2 biologics. AM: Alveolar macrophages; AEC: airway epithelial cells; DC: dendritic cells; IFN: Interferon; IL: Interleukin; ILC2: type 2 innate lymphoid cells; IRF: interferon regulatory factor; PAMP: Pathogen-associated molecular pattern; PRR: pattern recognition receptor; RV: Rhinovirus; SCFA: Short Chain Fatty Acid, TSLP: Thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

6.1. Immunostimulatory therapeutics

As we have shown earlier, asthmatic children may display an impairment of PRR signaling that leads to susceptibility to infection-induced asthma attacks. One of the strategies to enhance their anti-viral responses could involve stimulation of PRR. This strategy has only been tested in pre-clinical and adult studies. Following promising results from pre-clinical studies [149], Silkoff, et al. reported results of a clinical trial assessing the effect of CNTO3157, a TLR3 agonist, upon in vivo inoculation of RV-A16 in adult subjects with mild-to-moderate asthma [150]. The molecule was ineffective in blocking the effect of RV-16 challenge on the onset of asthma exacerbation, without effect on asthma symptoms nor lung function. Additionally, all post-inoculation exacerbations occurred in the CNTO3157 group, and two were severe, thus pointing toward a lack of efficacy and safety of the TLR3 targeting drugs.

Another way of activating PRR and associated signalling pathways could therefore be the administration of PAMP-like adjuvants or particles. Some teams have hypothesized that Poly I:C, a double stranded RNA that activates TLR3 and intracellular receptors, might modulate anti-viral responses. Preclinical studies have shown contrasting results, with promising effect in the context of Influenza A virus infection [52], [151], but concerns regarding its safety. Indeed, Tian, et al. have described, in a mouse model, a prolonged IFN response upon S. pneumonia and S. aureus infection, inducing an impaired bacterial clearance [152]. We have also demonstrated in a murine model of allergic asthma that TLR3 ligands can enhance the Th2 response [153]. Thus, the exact consequences of administering exogenous TLR ligands (including TLR7-8) in humans are still unknown and their potential role in bacterial secondary infections in the lungs need to be addressed.

Another immunomodulatory strategy, particularly appealing in pediatric asthma, could rely on the administration of bacterial lysates [154]. Two main therapies have been described: polyvalent mechanical bacterial lysates (PMBL®) and Broncho-Vaxom OM-85 BV. They contain lysates of 8 pathogenic bacteria including H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae. Both PMBL® and OM-85 administration have proven to be efficient in preventing respiratory tract infections in adult and pediatric patients with chronic bronchitis and/or history of recurrent chronic infections [155], [156], [157], [158], [159]. Interestingly, in a trial conducted in elderly COPD patients, Ricci, et al. observed a reduced number of seroconversion against numerous viral pathogens in patients treated with PMBL®, as well as a better control of the number of all infectious episodes and COPD exacerbations, suggesting that the preventing effect of PMBL® on acute infections was not only on bacterial infections, but also on viral infections [160]. In 152 school-aged children with allergic asthma, Emerick, et al. have described a reduction of exacerbations after 12 weeks of treatment with PMBL®, and no serious adverse event, although no improvement of asthma control scores were achieved [161]. In 75 preschool children with recurrent wheeze, Razi, et al. demonstrated that OM-85 BV reduced the rate and duration of wheezing episodes in the 12 months following the treatment initiation, and reduced the number of acute respiratory tract illnesses [162]. Finally, in toddlers aged 6–18 months, a clinical trial is ongoing to assess the preventive effect of OM-85V on the onset of first wheeze episode related to lower respiratory tract infection during a 3 years observational period [163]. Regarding the mechanisms of action, prevention of acute respiratory infections was not induced by purified LPS or bacterial DNA, suggesting that other PAMP contained in bacterial lysates would activate innate immunity and lead to promotion of type 1 inflammation by DC [164], [165], [166].

Altogether, immunostimulatory therapeutics may represent a promising strategy as additional treatments to prevent asthma attacks but their safety and efficacy need to be properly addressed. Because multiple microorganisms may be involved in acute asthma, it remains also unclear whether they would have an impact on the onset and severity of acute asthma attacks in children.

6.2. Therapeutics enhancing anti-viral responses

Anti-microbial peptides, among which LL-37, are key molecules of the innate immune responses against both viruses and bacteria. Thus, it has been hypothesized that supplementing with LL-37 or inducing its production among AEC could enhance anti-infectious defenses. Sousa, et al. have tested the effect of exogenous cathelicidin on RV-1B replication after inoculation on cultures of AEC [167]. They reported that exogenous LL-37, as well as homologous porcine cathelicidins, either administered prior or after infection, displayed antiviral activity against RV by reducing the metabolic activity of infected cells. However, one preclinical study in a mouse model of asthma showed in vivo a deleterious effect of exogenous cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide in airway inflammation and responsiveness [168], and to our knowledge, there is no published study in vivo in humans. Nevertheless, promising results regarding vitamin D supplementation on the release of LL-37 by AEC in in vitro experiments have been published [169], [170], [171]. In clinical studies, there is evidence toward a protective effect of vitamin D supplementation on risk of acute respiratory infections in children [172]. Although there are other effects of vitamin D that might explain its clinical efficacy [80], [173], there is a well-studied biological link between vitamin D and host microbial peptides, via the translocation of vitamin D to the nucleus of AEC, where it activates Vitamin D responsive elements in promoter regions of anti-microbial peptide genes such as LL-37 [52], [171], [174]. Hence, targeting the vitamin D/cathelicidin axis could represent a promising strategy during acute asthma in children.

As studies have shown deficient IFN responses in asthmatic patients, it has been hypothesized that IFN supplementation upon viral infection could enhance anti-viral responses and reduce asthma attacks severity. Interferon therapies (pegylated IFN-α in association with ribavirin) have first been developed in other diseases such as in hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus [175], [176]. Ribavirin is a synthetic guanosine nucleoside that impairs the synthesis of viral mRNA [52]. Its clinical utility, upon respiratory virus infection, has been shown in RSV, Adenovirus, RV, or in (SARS)-CoV immunocompromised patients [177], [178], [179], [180]. Since exogenous IFNs reduced RV replication in in vitro cultures of RV-infected AEC from asthmatic patients [181], a trial was initiated in 147 adult asthmatic patients developing symptoms of viral infection (68% RV) to evaluate the efficacy of inhaled IFN-β treatment for 14 days [182]. Overall, it did not improve asthma symptoms, but it enhanced morning peak expiratory flow recovery and reduced the need for additional treatment, i.e. oral corticosteroids or antibiotics. In an exploratory analysis of the subset of more difficult-to-treat patients, IFN supplementation improved asthma control questionnaires. In addition, it boosted anti-viral innate immunity with persistent elevated serum levels of CXCL10, and decreased levels of pro-inflammatory molecules such as CCL4 and CXCL8. In the INEXAS phase 2 trial, designed to assess efficacy of inhaled IFN-β1a for 14 days to prevent asthma exacerbations in adults, McCrae, et al. also reported improvement in the morning peak expiratory flow in the treated arm compared with placebo, but the study stopped early [183], [184]. No study has yet been conducted in pediatric patients.

Collectively, anti-viral therapies could represent potential therapies in the treatment of acute asthma attacks in children. However, the exact timing of administration upon viral infection and onset of acute asthma, and the population of children who might benefit from these strategies remain to be determined.

6.3. Role of anti-microbial therapeutics