Abstract

As a worldwide disaster, the COVID-19 crisis is profoundly affecting the development of the global economy and threatening the survival of firms worldwide. It seems unavoidable that this natural disruption has hit the global economy and produced a huge crisis for firms. This study explores how firms in China are innovating their marketing strategies by critically identifying the typology of firms’ marketing innovations using two dimensions, namely, motivation for innovations and the level of collaborative innovations. This research also explores the influence of the external environment, internal advantages (e.g., dynamic capabilities and resource dependence), and characteristics of firms on Chinese firms’ choice and implementation of marketing innovation strategies. It provides valuable insights for firms to respond successfully to similar crisis events in the future.

Keywords: COVID-19 crisis, Firms in China, Typology, Marketing innovation strategies, Dynamic capabilities, Resource dependence

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis, as a worldwide disaster, has a significantly negative impact on the development of the global economy. The latest data show that in China, although the government took effective measures to stop the virus from spreading, GDP in the first quarter of 2020 fell by 6.8% in comparison with an increase of 6.1% in 2019 (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2020). At same time, it is obvious that this worldwide disaster has also brought a huge crisis to firms not only in China but also in most countries, which has attracted attention to research on what firms should do to survive unexpected disasters in the future. This sudden crisis requires firms worldwide and in China to formulate and implement proper strategies for crisis management.

Prior research shows that marketing innovations could help firms survive risks (Naidoo, 2010). However, previous studies on crisis management focus more on topics such as organizational capabilities (Andreou et al., 2017, Parker and Ameen, 2018), corporate response (Hale et al., 2005, Runyan, 2006), human resource management (Harvey and Haines Iii, 2005, Lee and Warner, 2005, Sanchez et al., 1995), and corporate social responsibility (Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015). These research findings are undoubtedly significant for firms’ crisis management, but marketing innovation, as a significant form of innovation, has received less scrutiny in research on crisis management, with the exception of Naidoo (2010). Further analysis of Naidoo (2010) finds that it focuses on empirically revealing the link among marketing orientation, marketing innovation capabilities, competitive advantages, and firm survival in the context of general economic crisis, and defines marketing innovation capabilities as incremental improvement in terms of marketing tactics (i.e. marketing mix) rather than in perspective of marketing strategy. It fails to identify the typology of marketing innovation strategies in crisis. In addition, it also fails to investigate how a firm should design, choose, and implement proper marketing innovation strategies as a response to the crisis of Covid-19 in particular, which is quite different from the general economic crisis in the history.

Specifically, during the crisis of Covid-19, consumers’ demands and purchasing behaviors have been changing fundamentally (Kantar, 2020a), which makes it much more significant for a firm to rely on innovating its marketing strategies for survival. For example, people must isolate themselves at home and decline physical contact to prevent infection; thus, firms must pay more attention to developing and strengthening their online business by rapidly marketing innovations. Furthermore, among all affected countries, China was the first country to be hit heavily by COVID-19 crisis, and the first to manage to recover as well. Thus practices of firms in China provide sufficient evidence of marketing innovation strategies that are significant contributing factors for firms’ survival during the COVID-19 crisis. Besides, study of firms in China could provide firms in other countries lots of experience in dealing with the crisis and recovering in its aftermath. Hence, to address the above research gap, this study is intended to focus specifically on firms in China, and explores what kind of marketing innovation strategies firms should adopt and how firms should choose and implement specific marketing innovation strategies more effectively to respond to the rapidly changing consumption patterns of customers to survive and recover from the sudden COVID-19 crisis.

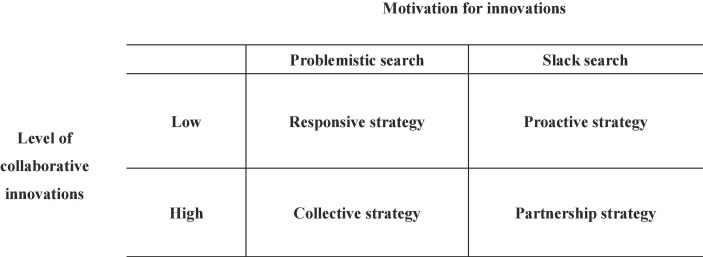

Marketing innovation strategies are defined as firms’ commitments to involving new or significantly improved marketing methods that enable firms to efficiently use their resources to meet the demand of customers and create superior customer value (Hunt and Morgan, 1995, Hurley and Hult, 1998, OECD, 2005). This study develops a typology of the marketing innovation strategies of firms under crisis management in two dimensions: motivation for innovations and the level of collaborative innovations. In this typology, four marketing innovation strategies are identified as proactive responses to the COVID-19 crisis based on the successful experiences of firms in China. Furthermore, this research explores how firms should properly choose and implement specific marketing innovation strategies based on an in-depth analysis of firms’ external factors, internal advantages (i.e., dynamic capabilities and resource dependence), and their own characteristics, which enriches the literature related to crisis management and provides new scenarios for research on marketing innovations.

This study begins with an overview of the dominant challenges firms face in the COVID-19 crisis and then develops a typology of marketing innovation strategies for firms to choose, which is followed by a comparison and discussion of four marketing innovation strategies. Furthermore, this study analyzes how firms should choose and implement proper strategies. The research concludes with a discussion of theoretical and practical implications.

2. Challenges for firms in the COVID-19 crisis

Disasters inevitably bring crises to firms (Benson & Clay, 2004). In the three months since the end of Jan. 2020, China’s economy has been heavily influenced by the COVID-19 crisis. People are showing great concern about health and safety, which has resulted in fundamental changes in their preferences and purchasing patterns. Firms in China have been highly affected and are seeking new market opportunities during the ongoing crisis. A survey of 995 firms from China shows that approximately 85.01% of them face the risk of bankruptcy because of the significant drop in operating income and the lack of cash flow if the crisis cannot be addressed successfully within three months (Zhu, Liu, & Wei, 2020). Another survey on the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on business management shows that firms generally face a sharp reduction of orders, cost pressures such as rent, wages and taxes, a general increase in the prices of raw materials, insufficient demand, and difficulty in finding alternative suppliers (Wen, Wei, & Wang, 2020). Furthermore, due to home quarantine, consumers’ purchasing activities have largely decreased. According to Kantar's market research, consumers' consumption attitudes have tended to be more conservative after the outbreak of COVID-19 and they prefer to reduce unnecessary expenses (Kantar, 2020a), which resulted in a sharp decline in firms’ revenue in the first quarter of 2020.

In Chinese, a crisis is called “Wei Ji”, meaning both a danger and an opportunity. More firms in China are striving to survive the COVID-19 crisis. Overcoming difficulties during the crisis and transforming the crisis into an opportunity are common choices of all firms in China. Among the surviving firms in China, a majority perform fairly well in marketing innovations to adapt quickly to turbulent, uncertain, and ambiguous environments. For example, weak consumer demand is one of the greatest challenges in the COVID-19 crisis. Therefore, based on deep insight into the changes in consumers' psychology and behaviors during home isolation, many retailers and even some leading manufacturers choose to use e-commerce livestreaming as a new channel that can be adapted to the policy of home quarantine and makes it more convenient for consumers to obtain access to the products or services they need.

The literature on crisis has emphasized that firms need to find a survival mechanism (e.g., Champion, 1999), and innovation capability has been found to be the key mechanism for organizational growth and renewal (Lawson & Samson, 2001). Especially in times of environmental turmoil such as natural crises, firms need to realize the need for innovations to resist destruction (Danneels, 2002, Schumpeter, 1950). In the context of sudden disasters such as the COVID-19 crisis, technological innovations always require a long research and development cycle (Bushee, 1998), while marketing innovations (compared to technological innovations) can be implemented relatively quickly to adapt to the new and changing demand of customers. Therefore, marketing innovation is an effective strategy for firms’ survival during the COVID-19 crisis (Naidoo, 2010). Thus, the rest of this study will identify and discuss the feasible marketing innovation strategies chosen by firms in China to provide access to consumers more effectively and stimulate more consumption and will provide valuable insights for firms to survive and recover from the COVID-19 crisis.

3. Typology of marketing innovation strategies in the COVID-19 crisis

As mentioned above, marketing innovation strategies refer to firms’ commitments to new or significantly improved marketing methods that enable firms to use their resources efficiently to meet the demand of customers and create superior customer value (Hunt and Morgan, 1995, Hurley and Hult, 1998, OECD, 2005). To survive the COVID-19 crisis and seek possible market opportunities, firms in China in almost all industries have explored possible options of marketing innovation strategies to different degrees and in different forms. To more precisely identify the marketing innovation strategies firms adopt during the COVID-19 crisis, two conceptual dimensions are introduced to develop an analytical framework for firms to consider.

The first dimension describes the motivation for innovations. This dimension highlights the degree of impact a firm is suffering during the crisis. Prior research suggests that risk-taking activities are responses to firms’ performance feedback (Chen and Miller, 2007, Chrisman and Patel, 2012, Joseph et al., 2016). According to the behavioral theory of the firm (Cyert & March, 1963), if a firm’s performance is lower than its expected level, the firm has a strong incentive to initiate problemistic search. That is, the firm looks for solutions to its key problems (March, 1988), thereby increase R&D investment, conduct M&A, or engaging in other risk-taking behaviors (Xu, Zhou, & Du, 2019). When a firm’s performance is higher than the expected level, the firm will have sufficient resources and abilities to start a slack search. That is, the firm may take advantage of its slack resources and turn them into long-term competitive advantages (O'Brien & David, 2014). Therefore, during the COVID-19 crisis, according to the various degrees of impact, firms usually have different motivations for innovation. In other words, firms in China may have problemistic searches or slack searches for their own choices in the COVID-19 crisis. To survive the crisis, highly affected firms tend to choose problemistic searches and manage to innovate their marketing strategies to keep their existing business and retain their current user groups. In comparison, other firms that have not suffered sharp shocks tend to prefer slack searches and make full use of any possible new opportunities in the COVID-19 crisis to devote themselves to marketing innovations to expand their business or gaining more consumers.

The second dimension refers to the level of collaborative innovations, which distinguishes whether the marketing innovation strategy is primarily based on a firm itself or is based in collaboration with others. This depends on whether a firm has enough resources and capabilities to innovate independently. For any firm, innovations are critical but challenging tasks, and they usually involve seeking new ideas, new tools, or new opportunities to upgrade existing businesses or to create new business (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). If a firm’s own business can be upgraded or it can develop a new business with its own resources and capabilities, it may choose to achieve marketing innovations independently. Otherwise, a firm may tend to choose to co-innovate with other firms by sharing complementary resources and competencies with each other (Doz et al., 2000, Grandori and Soda, 1995, Rothwell and Dodgson, 1991).

The two dimensions mentioned above represent four prototypical marketing innovation strategies (see Fig. 1 ). A firm that is suffering from the COVID-19 crisis can choose and implement a specific marketing innovation strategy that suits it best based on this framework to overcome risks and seize opportunities. As shown in Fig. 1, the first upper left quadrant represents a strategy that focuses on problemistic search and independent innovations, which can be called the responsive strategy in the COVID-19 crisis. It occurs when a firm must achieve marketing innovations for its existing business (for example, innovating its market channels) to restore its performance. Firms that have been hit hard by the crisis may prefer this specific responsive strategy because they usually have stronger motivation for a problemistic search to find new solutions to recover from the COVID-19 crisis. When choosing this strategy, firms need to deploy their own resources and perform marketing innovations to adapt to the new demand pattern of their target customers to realize the survivability of their existing businesses. Since consumers do not have the opportunity to consume offline due to home quarantine during the COVID-19 crisis, firms whose orders of products or services were acquired only by interaction with consumers offline are significantly influenced. In response, they may manage to establish a new e-channel of marketing to survive. One example of this responsive strategy is that firms take advantage of rapidly emerging Internet platforms where transactions can be made without traditional interpersonal contact and transfer all (or at least part of) traditional business to online channels (e.g., Chen and Zhao, 2020, ChinaSSPP.com, 2020a, Lu, 2020). As a result, e-commerce livestreaming is becoming increasingly popular during the COVID-19 crisis for online retailing, which has emerged in the last several years. At the beginning, online celebrities shared their experiences of product consumption, which gradually evolved into product recommendations in collaboration with firms (Cunningham, Craig, & Lv, 2019). During the COVID-19 crisis, Peacebird, a clothing brand, has rapidly adopted this specific strategy, inviting superstars, online celebrities, and even corporate CEOs to sell goods in live broadcasts and develop a new virtual connection with their existing customers (Zhou, 2020). Relevant evidence shows that with this marketing innovation strategy, the average daily retail sales of Peacebird exceeded 8 million during the COVID-19 crisis (ChinaSSPP.com, 2020a).

Fig. 1.

Typology of marketing innovation strategies in COVID-19 crisis.

The second lower left quadrant represents a strategy that focuses on problemistic search and collaborative innovation. It is called collective strategy in the COVID-19 crisis. In this specific strategy, the firms have also been hit hard by the crisis, but they have insufficient resources and capabilities to rapidly upgrade their business independently, such as channel transfer, due to their business restrictions. Thus, based on the motivation of problemistic search, firms that use this strategy tend to adopt collaborative innovations and share complementary resources and competencies with other firms. This strategy can not only earn profits from new business by leveraging existing resources but also contributes to revitalizing existing business for the firm. For example, during the COVID-19 crisis, residents seldom drive their cars, so there is almost no business for gas stations (Finance.sina, 2020a). The product characteristic of gasoline makes it almost impossible to be sold and fueled online. This situation forced Sinopec to analyze its business strategy very carefully, and it discovered that it was becoming more difficult for residents to buy food outside as they did before the crisis (Finance.sina, 2020b). Thus, Sinopec cooperated with local food suppliers and launched a new contactless service based on its widespread gas station outlets in communities that makes it very convenient for people to buy fresh food regardless of whether they need to fuel their cars (Cuba, 2020). This cross-border collaborative innovation provides Sinopec with new opportunities to develop diverse businesses and overcome the bottleneck faced by the original refueling business during the crisis (Ocn.com, 2020).

The third upper right quadrant represents a strategy that focuses on slack search and independent innovations. It is called proactive strategy in the COVID-19 crisis, and it occurs when a firm has been relatively unaffected by the crisis and wants to use its accumulated slack resources of Internet technologies to capture the unique market demand in the current environment. More precisely, some firms, such as e-commerce platforms and social media platforms, are less affected by the crisis because of their “contactless” characteristics (Kantar, 2020b) During the COVID-19 crisis, they can take advantage of their existing user base and make full use of their own accumulated resources and capabilities, such as digital technologies, to optimize their businesses independently in response to changes in environments, such as consumers’ need to isolate at home and mainly use their smartphones to make purchases (Kantar, 2020b). By adding new businesses, firms can not only provide existing users with diversified offerings but also acquire more potential customers. For example, Suning.com, an e-commerce platform in China, has lengthened the duration of livestreaming to 12 uninterrupted hours to meet the heterogeneous watching time preference of consumers and maximize audience coverage (Chinaz.com, 2020).

The fourth and final lower right quadrant represents a strategy that focuses on slack search and collaborative innovations. It is called partnership strategy in the COVID-19 crisis and indicates that firms that are less affected during the crisis can collaborate with other firms and develop new businesses based on the needs of consumers to expand their user base. The key for firms that adopt this specific strategy is to develop new businesses by combining their internal advantages of digital resources with the external complementary resources of their partners. In this way, they can develop new markets and acquire new customer groups. Taking the Tik Tok short video platform as an example, its users previously shared their lives on the platform in the form of short videos. During the crisis, this type of social media platform gained great market growth (199IT, 2020). At the same time, firms such as museums and movie theaters were unable to generate revenue because of home quarantine. It is extraordinarily hard for these types of offline firms to build a new online business. Therefore, Tik Tok seized upon the needs of potential users and launched new services such as online exhibitions, online movie playback, and online education in the livestreaming sector (199IT, 2020).

These four types of marketing innovation strategies and their characteristics are summarized in Table 1 . To deepen the understanding of the typology and provide firms with guidelines on how to choose and implement proper marketing innovation strategies, in-depth interviews with managers were conducted along with an intensive review of prior research to provide a holistic view of the similarities and differences of these four types of marketing innovation strategies. In doing so, this research analyzes the external environment, internal advantages (i.e., dynamic capabilities and resource dependence), and main characteristics of firms (DeSarbo et al., 2005, Hambrick, 1983, Mårtensson and Westerberg, 2016).

Table 1.

Comparison and example firms of four types of marketing innovation strategies.

| Strategy | Motivation of innovations | Level of collaborative innovations | Strategy choice |

Strategy implementation | Example firms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of impact | Core dynamic capabilities | Resource dependence | Consumption scenarios | |||||

| Responsive strategy | Problemistic search | Low | Hard | Reconfiguration capabilities | Low | Physical contact | Maintaining existing business through channel transformation from offline to online | Peacebird; China Construction Bank; China Evergrande Group |

| Collective strategy | Problemistic search | High | Hard | Leveraging capabilities | High | Physical contact | Benefiting from the collaborative business and revitalizing existing business through new business | Sinopec |

| Proactive strategy | Slack search | Low | Light | Reconfiguration capabilities | Low | Contactless | Taking advantage of the existing user base to develop new business, then acquiring both new business and consumer base | Suning.com; Tencent |

| Partnership strategy | Slack search | High | Light | Leveraging capabilities | High | Contactless | Expanding customer base through complement collaboration, then acquiring both new business and consumer base | Tik Tok |

4. Choices and implementation of a specific marketing innovation strategy

Responsive strategy in the COVID-19 crisis. In terms of the external environment, when firms are greatly affected by the COVID-19 crisis, such as firms whose offline businesses take a large percentage, this strategy can be used by innovating the existing business to alleviate the huge impact of the crisis (Du, 2018). With regard to internal advantages, since this marketing innovation strategy relies on the firm's own resources and capabilities, it is suitable for a firm with relatively lower dependence on external resources (Gandia & Gardet, 2019) and stronger reconfiguration capabilities, which refers to upgrading and optimizing existing business through the transformation and reconfiguration of resources within the organization (Bowman and Ambrosini, 2003, Makkonen et al., 2014).

Firms that choose this strategy are mainly those whose businesses are based on offline physical interpersonal contact and that are able to independently integrate and reconfigure their offline resources and conduct marketing innovation by transferring the original marketing channels of their existing business to online channels. This transfer provides the opportunity to maintain the normal operation of their existing business while responding successfully to the rapidly changing purchasing patterns of customers during the COVID-19 crisis. Taking the clothing brand Peacebird as an example, its core business is offline retailing in large shopping malls (ChinaSSPP.com, 2020b). During the crisis, some of this firm's offline stores were forced to suspend business due to the sharp reduction of offline consumer demand (Zhou, 2020). Relying on sensitive insights into marketing demand, the firm quickly reorganized and configured the inventory of closed stores, transferred offline store employees to online marketing teams, and provided employees with targeted online marketing knowledge training (ChinaSSPP.com, 2020a). Finally, with the help of livestreaming and social media platforms to reach consumers, Peacebird completed a successful channel transformation and survived the crisis (Zhou, 2020). Similarly, the China Construction Bank launched an online “cloud studio” to provide financial services to customers through WeChat applets (Lu, 2020), and China Evergrande Group, a real estate company, implemented projects to obtain signatures on smart phones and conduct housing transactions online across the country (Chen & Zhao, 2020).

Collective strategy in the COVID-19 crisis. In terms of the external environment, firms that are heavily impacted during the COVID-19 crisis can also consider this strategy. However, when choosing between a responsive strategy and collective strategy, firms need to consider two factors. On the one hand, with regard to internal advantage, collective strategy is much more suitable for business innovations that are highly dependent on external resources. Because of the constraints of these firms’ own resources and capacities, they must develop their new businesses through collaboration with external firms to create collective value as a system (Gandia and Gardet, 2019, Lusch et al., 2010). Moreover, firms that choose this specific strategy need to leverage their existing resources and capabilities, which involves integrating the advantages of their original business into a new business (Makkonen et al., 2014). On the other hand, the consumption scenario of the original offerings provided by firms also affects their choices. For firms whose primary products cannot be provided online, it is much more suitable for them to choose a collective strategy to achieve business innovations.

When implementing this strategy, firms can develop new business by collaborating with other firms during the crisis. Sinopec, for example, has adopted this marketing innovation strategy and become successful in China (Finance.sina, 2020b). The firm's fueling business, which depends primarily on offline physical contact, declined due to home quarantine. To solve this problem, Sinopec seized its customers’ new demand opportunity, i.e., the demand for fresh food with no physical interpersonal contact; it quickly cooperated with the fresh food retailer Freshippo of the Alibaba Group and launched grocery shopping with contactless distribution at its widespread gas station outlets (Cuba, 2020). Citizens can buy, for example, fresh vegetables at various gas station outlets of Sinopec, and then the frontline employees take these fresh vegetables directly to the car trunk of the customer, which enables customers to complete the transaction in a more convenient and contactless way since customers have no need to leave their cars or even open the car window. On the basis of its gas station outlets, Sinopec makes full use of the resources and logistics of Freshippo of the Alibaba Group in the fresh food supply chain to achieve business innovations. Furthermore, this new business drives the demand of the existing consumer base for refueling business to some degree, enabling the original refueling business to be revitalized (Ocn.com, 2020).

Proactive strategy in the COVID-19 crisis. From the perspective of external environments, firms that are less affected by the COVID-19 crisis, such as some Internet firms that focus on online businesses, can adopt this specific strategy. As far as internal advantages are concerned, this marketing innovation strategy is suitable for business innovations with low dependence on external resources (Gandia & Gardet, 2019). That is, firms can independently develop new business by prioritizing the new demand of their existing customers during the COVID-19 crisis. Firms that choose this strategy must have strong capabilities to integrate their resources of existing customer bases (i.e., reconfiguration capabilities) (Bowman and Ambrosini, 2003, Makkonen et al., 2014) to design and launch their new businesses more effectively.

When implementing this strategy, firms can develop new businesses to meet the special demands of existing customers during the COVID-19 crisis. Taking the Internet retailing firm Suning.com as an example, it is a B2C online shopping platform that offers products including traditional home appliances, 3C appliances, and daily necessities (Suning.com, 2020). During the COVID-19 crisis, Suning.com seized upon the popularity of online livestreaming services and launched a 12-hour uninterrupted livestreaming service in response to increases in most users’ online browsing times. Through the extension of the livestreaming time, Suning.com met the heterogeneous demands of customers for a more flexible time schedule for watching livestreaming during the COVID-19 crisis, which in turn gave existing consumers diversified online offerings and attracted new customers. Another example is Tencent. As the largest social media and technology firm in China, it has a large user base. To seize upon users' demands for remote office and video conferencing as a result of home quarantine, Tencent has developed a new app called Tencent Conference, which has been preferred and widely adopted during the crisis.

Partnership strategy in the COVID-19 crisis. From the perspective of external environments, firms that are less affected during the COVID-19 crisis can adopt this specific strategy as an alternative. Both proactive and partnership strategies are applicable to firms that provide offerings that service online consumption scenarios. However, when choosing between these two strategies, firms need to consider their own internal advantages. Unlike a proactive strategy, the partnership strategy is suitable for firms that lack internal resources to develop new business independently. More precisely, because of the resource constraints associated with the development of new businesses, firms must seek potential partners whose businesses are complementary to their own and rely on the complementary resources of external partners to develop new businesses and expand their own customer base. Furthermore, to adopt this strategy, firms must have stronger leveraging capabilities, which refers to taking advantage of the original business resources to provide sufficient support for the development of new businesses (Makkonen et al., 2014). Thus, through cooperation, firms can provide existing customers with new offerings and further expand their customer base by taking advantage of the complementary resources of their partners.

When implementing this strategy, firms should develop new offerings through complementary collaboration with other firms. This kind of collaborative innovation makes full use of the advantages of both partnering firms to achieve a win–win situation for all stakeholders (Huang & Yu, 2011). Taking Tik Tok as an example, the firm implemented this strategy well during the COVID-19 crisis. Tik Tok is a social media platform that provides short video and livestreaming services to users and relies primarily on user-generated content to increase the number of users (Sohu, 2019). Under current resource constraints, to seize new marketing opportunities based on increased demand for online services, Tik Tok collected various life service resources, such as exhibitions, movies and education, on its platform with its own platform advantages and acquired more new users (199IT, 2020). In addition, firms that cooperate with Tik Tok have improved their own performance, thereby mitigating the negative impact of the COVID-19 crisis on these firms (Sohu, 2020).

In summary, the four strategies identified in this study are based on the refinement of Chinese firms’ marketing innovation practices during the COVID-19 crisis. In fact, a firm may operate multiple businesses at the same time. Therefore, when choosing among the four specific marketing innovation strategies, it is possible for firms to adopt one specific strategy or a combination of several strategies to cope with the COVID-19 crisis.

5. Discussion and implications

COVID-19 is still spreading all over the world, and firms are profoundly affected by the sudden crisis. Managers must decide how to adapt their marketing strategies to disruptive environments. In this research, a typology of marketing innovation strategies is identified in two dimensions, i.e., the motivation for innovations (problemistic search or slack search) and the level of collaborative innovations (independent or collaborative). This study offers innovative insights into how firms may choose among these four strategies to survive the COVID-19 crisis. Specifically, as far as both external environments and internal advantages are concerned, when a firm is exposed to a greater degree of external impacts, it is reasonable to choose the responsive strategy that requires the firm to have stronger reconfiguration capabilities and independently optimize existing business. Otherwise, it is wise for the firm to choose the collective strategy that requires stronger leveraging capabilities and higher dependence on partners’ complementary resources to launch new businesses. When external impacts on a firm are relatively light and the firm has advantages in reconfiguration capabilities and resources that enable the firm to independently develop a new business based on its existing customer base, it is better for the firm to choose the proactive strategy. By contrast, when a firm has stronger leveraging capabilities and relies on the complementary resources of partners to develop a new business, it is more suitable for the firm to choose the partnership strategy. In addition, firms need to take their own characteristics into consideration when they decide which specific marketing innovation strategy to choose. For example, when the products or services a firm provides require more physical contact between the firm and its customers, the firm must choose the responsive strategy or the collective strategy during the COVID-19 crisis. In contrast, when the products or services a firm provides can usually be accessed through contactless consumption scenarios, the firm may decide to choose the proactive strategy or the partnership strategy.

5.1. Theoretical implications

This study makes two main contributions to knowledge of crisis management. First, this research highlights the significant role of marketing innovation strategies in crisis management. Although prior studies acknowledged the importance of marketing innovation due to its ability to provide diversified offerings (Doyle & Bridgewater, 1998), less attention has been paid to its role in crisis management. The current research fills this gap by identifying a typology of the marketing innovation strategies of firms in China in two dimensions, i.e., the motivation for innovation (problemistic search or slack search) and the level of collaborative innovation (independent or collaborative), and exploring how firms should choose among them in the COVID-19 crisis.

Second, this study extends knowledge about marketing innovation to crisis management. Although previous research highlights a strong link between marketing innovations and the likelihood of firms’ survival during crises, it regards marketing innovations only as capabilities of firms to improve their performance (Naidoo, 2010). The extant literature has not systematically investigated which marketing innovation strategies firms should choose and how they can implement them more effectively. This study addresses this research gap and explores how firms choose and implement their specific marketing innovation strategies by considering the external environments, internal advantages and characteristics of firms as a whole. Thus, this research enriches the literature related to crisis management and provides new scenarios for studies of marketing innovation.

5.2. Managerial implications

External crises are inevitable. COVID-19 has spread all over the world, and firms in most countries are experiencing a huge crisis. China is among the first countries that were influenced, and firms in China have been strongly affected during the crisis. Therefore, firms in China must explore feasible marketing innovations to survive the crisis. This article describes their successful experiences, proposes four choices of marketing innovation strategies, analyzes their differences and similarities by matching external environments and internal advantages, and provides insights into effective strategy implementation in the COVID-19 crisis. This study may help firms overcome difficulties during the COVID-19 crisis. It should be noted that the four marketing innovation strategies identified in this study are based on the business level of a firm. Therefore, if firms in the crisis have multiple businesses at the same time, they may have to choose one specific strategy for each of their businesses. For example, a firm may conduct both online and offline business at the same time; thus, managers can choose proper marketing innovation strategies for offline and online businesses. In addition, a firm may choose a combination of several marketing innovation strategies if required.

When firms in China choose and implement their marketing innovation strategies during the COVID-19 crisis, the possible outcomes are inseparable from China's institutional contexts and cultural background. For example, in terms of control of the COVID-19 crisis, the institutional advantages of China are of great significance. The concentration of resources by the Chinese government made it possible to strictly control the spread of the epidemic. Effective governance provided an external environmental guarantee for the potential effectiveness of the proper marketing innovation strategies of firms. Furthermore, Chinese culture is collectivistic (Hofstede, 1980, Triandis, 2018). In controlling the COVID-19 crisis, everyone in a firm, from the top to the bottom, gathers together to seek ways to overcome difficulties and survive the crisis. Taking livestreaming as an example, popular CEOs of many firms go into live broadcast rooms and present good selling points for their offerings, which embodies the collectivistic nature of Chinese culture. Therefore, when firms in other countries attempt to learn from the experience of firms in China and explore effective marketing innovation strategies, they may have to make certain adjustments based on the institutional system of their own country and the cultural characteristics of their employees and customers.

6. Limitations and future research

This study has certain limitations that call for future research. First, by exploring and identifying the marketing innovation strategies of firms in China during the COVID-19 crisis, this article combines crisis management with marketing innovation theory to demonstrate that marketing innovations can help firms in the COVID-19 crisis survive and recover based on an in-depth case analysis. However, there is no empirical test of our conclusions. Future empirical studies are needed to test and extend the findings of this research. Second, to obtain a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of crisis management during the COVID-19 crisis, future research should pay more attention to the generalization of the findings of this study by exploring the possible influences of the institutional system and cultural characteristics of the host countries. Finally, this research focuses only on how marketing innovation strategy contributes to the survival and growth of firms in crisis management. Future research should further explore the joint effects of other functional innovation strategies, such as human resource management, financial management, operations management, and information management, with marketing innovations to build a holistic framework to guide firms in surviving any crisis in the future.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (71725003).

Biographies

Yonggui Wang is the Changjiang Chair Professor of Marketing and Strategy, Vice President of Capital University of Economics and Business, Beijing, China. He received his PhD from City University of Hong Kong. His current research is on service marketing, value co-creation and CRM, innovation and international business. He has published more than 60 papers in Journal of Marketing, Journal of Operations Management, Journal of Management, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Business Research, Information & Management, Decision Support Systems, among others.

Aoran Hong is a PhD student at University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, China. His research interests focus on marketing strategy, inter-firm relationship management, international business, and innovation management.

Xia Li is a PhD student at University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, China. Her research interests focus on marketing strategy, service innovation, and international business.

Jia Gao is a postdoctoral researcher at University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, China. She got the PhD degree from the City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China. Her research interests focus on green innovation, industrial innovation and development.

Contributor Information

Yonggui Wang, Email: ygwang@uibe.edu.cn.

Aoran Hong, Email: ferrishong@163.com.

Xia Li, Email: vivianxiali@163.com.

Jia Gao, Email: gaojcr@126.com.

References

- 199IT (2020). The livestreaming data map of Tik Tok in 2020. http://www.199it.com/archives/1037843.html. Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Andreou P.C., Karasamani I., Louca C., Ehrlich D. The impact of managerial ability on crisis-period corporate investment. Journal of Business Research. 2017;79(Oct.):107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Benson C., Clay E. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2004. Understanding the economic and financial impacts of natural disasters. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman C., Ambrosini V. How the resource-based and the dynamic capability views of the firm inform corporate-level strategy. British Journal of Management. 2003;14(4):289–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bundy J., Pfarrer M.D. A burden of responsibility: The role of social approval at the onset of a crisis. Academy of Management Review. 2015;40(3):345–369. [Google Scholar]

- Bushee B.J. The influence of institutional investors on myopic R&D investment behavior. Accounting Review. 1998;73:305–333. [Google Scholar]

- Champion D. The price of undermanagement. Harvard Business Review. 1999;77(2):14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.R., Miller K.D. Situational and institutional determinants of firms' R&D search intensity. Strategic Management Journal. 2007;28(4):369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. & Zhao, Y. (2020). Demystifying the secret of China Evergrande Group 's online house transactions during COVID-19 crisis. https://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/2020-03-07/doc-iimxyqvz8469103.shtml. Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- ChinaSSPP.com (2020a). The average daily retail sales of domestic clothing brand Peacebird exceeded 8 million during COVID-19 crisis. http://www.chinasspp.com/News/Detail/2020-2-11/446723.htm. Accessed date: 28 April 2020.

- ChinaSSPP.com (2020b). How did Peacebird achieve average daily sales of more than 8 million when half of the offline stores were closed. http://www.chinasspp.com/News/Detail/2020-2-29/447380.htm. Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Chinaz.com (2020). Suning.com launched 12 hours livestreaming plan which involving 3280 stores. https://www.chinaz.com/2020/0221/1111809.shtml. Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Chrisman J.J., Patel P.C. Variations in R&D investments of family and nonfamily firms: Behavioral agency and myopic loss aversion perspectives. Academy of management Journal. 2012;55(4):976–997. [Google Scholar]

- Cuba L. What is the purpose of Sinopec that selling fresh products at gas stations? 2020. https://www.huxiu.com/article/340189.html Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Cunningham S., Craig D., Lv J. China’s livestreaming industry: Platforms, politics, and precarity. International Journal of Cultural Studies. 2019;22(6):719–736. [Google Scholar]

- Cyert R.M., March J.G. A behavioral theory of the firm. Englewood Cliffs, NJ. 1963;2(4):169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Danneels E. The dynamics of product innovation and firm competences. Strategic Management Journal. 2002;23(12):1095–1121. [Google Scholar]

- DeSarbo W.S., Anthony Di Benedetto C., Song M., Sinha I. Revisiting the Miles and Snow strategic framework: Uncovering interrelationships between strategic types, capabilities, environmental uncertainty, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal. 2005;26(1):47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle P., Bridgewater S. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1998. Innovation in marketing. The chartered institute of marketing; p. (pp. 225).. [Google Scholar]

- Doz Y.L., Olk P.M., Ring P.S. Formation processes of R&D consortia; which path to take: Where does it lead? Strategic Management Journal SI. 2000;21:239–266. [Google Scholar]

- Du K. The impact of multi-channel and multi-product strategies on firms' risk-return performance. Decision Support Systems. 2018;109:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Finance.sina (2020a). The sales of refined oil business at gas station dropped by more than 30% year-on-year in the first two months of 2020. http://finance.sina.com.cn/money/future/nyzx/2020-02-12/doc-iimxyqvz2234700.shtml. Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Finance.sina (2020b). Sinopec launched the grocery shopping at gas station to seize the business of fresh e-commerce. https://finance.sina.com.cn/chanjing/cyxw/2020-02-17/doc-iimxxstf1977930.shtml. Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Gandia R., Gardet E. Sources of dependence and strategies to innovate: Evidence from video game SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management. 2019;57(3):1136–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Grandori A., Soda G. Inter-firm networks: Antecedents, mechanisms and forms. Organization Studies. 1995;16(2):183–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hale J.E., Dulek R.E., Hale D.P. Crisis response communication challenges: Building theory from qualitative data. The Journal of Business Communication (1973) 2005;42(2):112–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick D.C. Some tests of the effectiveness and functional attributes of Miles and Snow’s strategic types. Academy of Management Journal. 1983;26(1):5–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey S., Haines Iii V.Y. Employer treatment of employees during a community crisis: The role of procedural and distributive justice. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2005;20(1):53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G.H. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1980. Culture’ s consequences: International differences in work-related values. [Google Scholar]

- Huang K.F., Yu C.M.J. The effect of competitive and non-competitive R&D collaboration on firm innovation. The Journal of Technology Transfer. 2011;36(4):383–403. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S.D., Morgan R.M. The comparative advantage theory of competition. Journal of Marketing. 1995:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley R.F., Hult G.T.M. Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: An integration and empirical examination. Journal of Marketing. 1998;62(3):42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph J., Klingebiel R., Wilson A.J. Organizational structure and performance feedback: Centralization, aspirations, and termination decisions. Organization Science. 2016;27(5):1065–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Kantar (2020a). Coronavirus outbreak’s impact on China’s consumption. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/OptUHteL3zGVHahnDolRDg. Accessed date: 28 April 2020.

- Kantar (2020b). COVID-19 Global Consumer Barometer Report. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/3dxiNOgLMU8Xs4tDAumvUw. Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Lawson B., Samson D. Developing innovation capability in organizations: A dynamic capabilities approach. International Journal of Innovation Management. 2001;5(3):337–400. [Google Scholar]

- Lee G.O., Warner M. Epidemics, labour markets and unemployment: The impact of SARS on human resource management in the Hong Kong service sector. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2005;16(5):752–771. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. The Beijing branch of China construction bank set up the cloud studio of account manager. 2020. https://www.financialnews.com.cn/zt/kjyq/202002/t20200218_179821.html Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Lusch R.F., Vargo S.L., Tanniru M. Service, value networks and learning. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2010;38(1):19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Makkonen H., Pohjola M., Olkkonen R., Koponen A. Dynamic capabilities and firm performance in a financial crisis. Journal of Business Research. 2014;67(1):2707–2719. [Google Scholar]

- March J.G. Variable risk preferences and adaptive aspirations. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 1988;9:5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mårtensson K., Westerberg K. Corporate environmental strategies towards sustainable development. Business Strategy and the Environment. 2016;25(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo V. Firm survival through a crisis: The influence of market orientation, marketing innovation and business strategy. Industrial Marketing Management. 2010;39(8):1311–1320. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China Preliminary accounting results of GDP in the first quarter of 2020. 2020. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202004/t20200417_1739602.html Accessed date: 18 April 2020.

- O'Brien J.P., David P. Reciprocity and R&D search: Applying the behavioral theory of the firm to a communitarian context. Strategic Management Journal. 2014;35(4):550–565. [Google Scholar]

- Ocn.com (2020). Will Sinopec's business of grocery shopping at gas station continue until the end of COVID-19 crisis? http://www.ocn.com.cn/keji/202003/zuagf04152901.shtml. Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- OECD . 3rd ed. OECD; Paris: 2005. Oslo manual: Guidelines for collecting and interpreting innovation data. [Google Scholar]

- Parker H., Ameen K. The role of resilience capabilities in shaping how firms respond to disruptions. Journal of Business Research. 2018;88:535–541. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell R., Dodgson M. External linkages and innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises. R&D Management. 1991;21(2):125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Runyan R.C. Small business in the face of crisis: Identifying barriers to recovery from a natural disaster 1. Journal of Contingencies and crisis management. 2006;14(1):12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez J.I., Korbin W.P., Viscarra D.M. Corporate support in the aftermath of a natural disaster: Effects on employee strains. Academy of Management Journal. 1995;38(2):504–521. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter J.A. 3rd ed. Harper and Row; New York: 1950. Capitalism, socialism and democracy. [Google Scholar]

- Sohu (2019). How to attract accurate fans on the Tik Tok platform? https://www.sohu.com/a/323783487_120144595. Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Sohu (2020). Will Tik Tok lose money by launching a free movie service on the platform. Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Subramaniam M., Youndt M.A. The influence of intellectual capital on the types of innovative capabilities. Academy of Management Journal. 2005;48(3):450–463. [Google Scholar]

- Suning.com (2020). https://www.suning.com/. Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Triandis H.C. Routledge; 2018. Individualism and collectivism. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H., Wei, Y., & Wang, S. (2020). Survey on Impact of COVID-19 No. 2: Report on the impact of COVID-19 crisis on the business management. https://www.sohu.com/a/385568115_476872. Accessed date: 28 April 2020.

- Xu D., Zhou K.Z., Du F. Deviant versus aspirational risk taking: The effects of performance feedback on bribery expenditure and R&D intensity. Academy of Management Journal. 2019;62(4):1226–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. Will this bring hope to domestic clothing brands that the average daily retail sales of domestic clothing brand Peacebird exceeded 8 million during COVID-19 crisis? 2020. https://www.sohu.com/a/372116735_100191058 Accessed date: 10 May 2020.

- Zhu, W., Liu, J., & Wei, W. (2020). A survey of 995 SMEs: 85% of companies have difficulty maintaining operations for 3 months. Chuangtoutiao. http://www.ctoutiao.com/2593858.html. Accessed date: 28 April 2020.