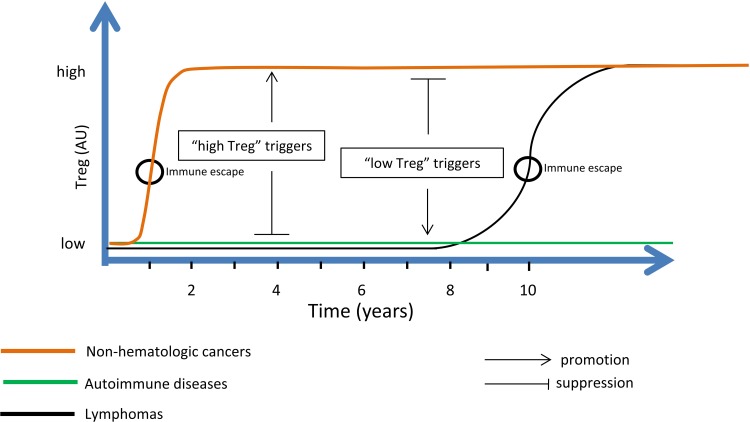

Figure 1.

TGFβ exerts an anti-tumor effect in early cancer development; however, it evolves into a pro-tumor effect as disease progresses. This functional switch, which may be regarded as an immune escape mechanism, occurs as TGFβ pathways are hampered with the result of a decreased anti-tumor suppressive effect by TGFβ. Other effects of TGFβ, such as immunosuppression, EMT, effect on fibroblasts, and effect on extracellular matrix, are all pro-tumor. Early cancer stages correspond to a “low Treg” disease when immune response is fully active. At advanced cancer stages, specific anti-tumor T cell activity is impaired while other pro-inflammatory components of the immune system are highly activated. This corresponds to a specific “high Treg” state of the disease. Therefore, cancers evolve from a “low Treg” state where tumor proliferation is controlled, into a specific “high Treg” state where this control loosens. Lymphoma is unique among cancers by the length of time it may reside at a “low Treg” state (years). During this indolent low-grade stage, lymphoma treatment is relatively effective. “High Treg” triggers promote “high Treg” states but suppress “low Treg” states. “Low Treg” triggers promote “low Treg” states but suppress “high Treg” states. For example, alcohol abuse, a “high Treg” trigger, increases the risk of most non-hematologic cancers but decreases the risk of lymphomas. Similarly, alcohol consumption confers a protection against autoimmune hypothyroidism. On the other hand, the same set of “low Treg” bacteria and parasites that promotes (indolent) lymphoma also promotes autoimmune diseases, all “low Treg” conditions.

Abbreviation: EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-beta; Treg, regulatory T cells.