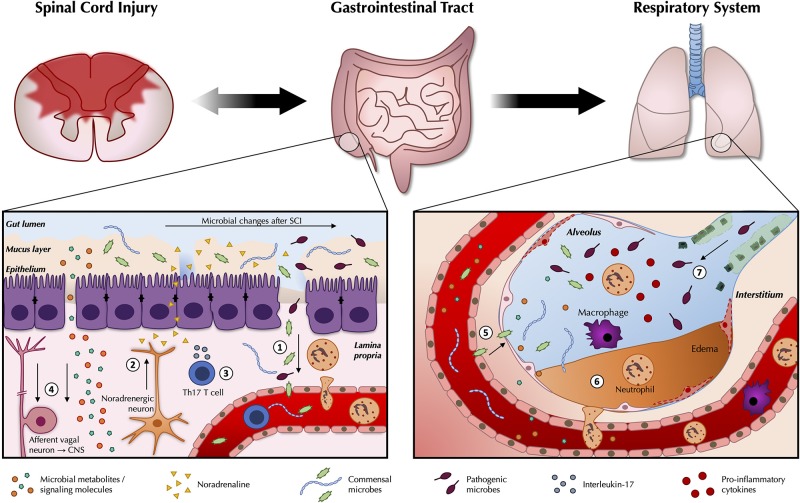

Figure 1.

Pathogenic changes in the gut microbiota after traumatic spinal cord injury. As part of the wider systemic response to SCI, inflammatory changes in the gut are likely to contribute to reduced intestinal function and barrier integrity (1). Leakiness of the gut epithelium can dysregulate the microbial community in the gut lumen and allow for bacterial translocation. Release of noradrenaline from post-ganglionic sympathetic terminals is thought to further contribute to gut dysbiosis (2). A greater abundance and/or expansion of specific pathobionts after SCI can induce a Th17 response, which propagates further inflammation (3). Afferent sensory feedback signals report perturbations in the intestinal environment to the brain via the vagus nerve, thereby completing the bidirectional loop between the gut and the central nervous system, while gut microbes release metabolites and signaling molecules such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that shape peripheral immunomodulatory processes (4). These changes may modulate the immune response to e.g., airway infections. Commensal microbes from the gut may also be able to take up inappropriate residence in the lungs (5). Local inflammatory changes in the lungs in response to SCI may compromise the respiratory epithelium (6), and interfere with local defense mechanisms against extraneous pathogens (7).