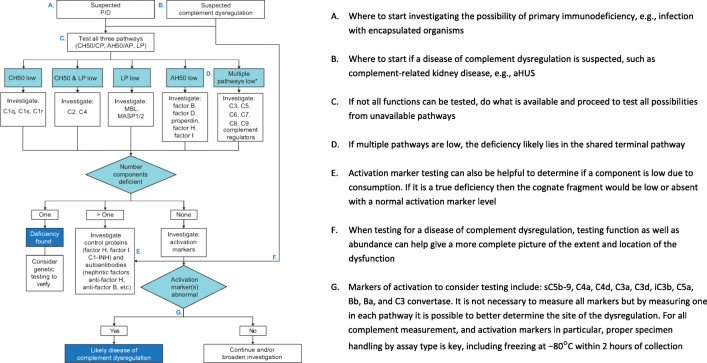

Fig. 2.

Algorithm for complement testing. a Where to start investigating the possibility of primary immunodeficiency, e.g., infection with encapsulated organisms. b Where to start if a disease of complement dysregulation is suspected, such as complement-related kidney disease, e.g., aHUS. c If not all functions can be tested, do what is available and proceed to test all possibilities from unavailable pathways. d If multiple pathways are low, the deficiency likely lies in the shared terminal pathway. e Activation marker testing can also be helpful to determine if a component is low due to consumption. If it is a true deficiency then the cognate fragment would be low or absent with a normal activation marker level. f When testing for a disease of complement dysregulation, testing function as well as abundance can help give a more complete picture of the extent and location of the dysfunction. g Markers of activation to consider testing include: sC5b-9, C4a, C4d, C3a, C3d, iC3b, C5a, Bb, Ba and C3 convertase. It is not necessary to measure all markers but by measuring one in each pathway it is possible to better determine the site of the dysregulation. For all complement measurement, and activation markers in particular, proper specimen handling by assay type is key, including freezing at − 80°C within 2 h of collection. AH50, alternative pathway hemolytic activity; aHUS, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome; AP, alternative pathway; C1-INH, C1 esterase inhibitor; CH50, complement hemolytic activity; CP, classical pathway; LP, lectin pathway; MASP, MBL-associated serine protease; MBL, mannose-binding lectin; PID, primary immunodeficiency. *The sample may have been improperly handled, or the patient has autoantibodies against complement components.