Abstract

Biomolecules such as nucleic acids and proteins constitute the cells and its organelles that form the crucial components in all living organisms. They are associated with a variety of cellular processes during which they undergo conformational orientations. The structural rearrangements resulting from protein–protein, protein–DNA, and protein–drug interactions vary in spatial and temporal length scales. Force is one of the important key factors which regulate these interactions. The magnitude of the force can vary from sub-piconewtons to several thousands of piconewtons. Single-molecule force spectroscopy acts as a powerful tool which is capable of investigating mechanical stability and conformational rearrangements arising in biomolecules due to the above interactions. Real-time observation of conformational dynamics including access to rare or transient states and the estimation of mean dwell times using these tools aids in the kinetic analysis of these interactions. In this review, we highlight the capabilities of common force spectroscopy techniques such as optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers, and atomic force microscopy with case studies on emerging applications.

1. Introduction

Single-molecule techniques have emerged as a powerful tool to study biological processes in isolation. The behavior of one protein molecule can be monitored at a time when it is present in a solution, crystal, or cell. These measurements allow us to identify distinct structural states, including transient or rare states which arise during the unfolding/refolding of proteins, allosteric regulation, and protein–protein, protein–DNA, or protein–drug interactions. These transient or rare states gets averaged out in ensemble measurements and hence are difficult to isolate. But single-molecule techniques unravel these hidden states and provide a better understanding of the above interactions. These transient or rare states may undergo a transition among themselves as well as to the folded, intermediate or unfolded states previously reported using X-ray crystallography, NMR, and other bulk spectroscopic techniques. Also, single-molecule experiments bridge the findings of classical biochemistry experiments and structural studies. In the case of clinically relevant proteins, some of these states might be of significant importance and can contribute to drug discovery. However, this largely depends on the temporal and spatial resolution of the technique. It is equally important that the detected signal is not an artifact.

Single-molecule studies could specifically elucidate the impact of crowding agents on the functions of biomolecules. Single-molecule experiments with RNA in the presence of the crowding agents (e.g., high-molecular-weight poly(ethylene glycol)) indicated that they stabilize the folded state of RNA, favoring their catalytic properties. With single DNA hairpins, it was observed that the hairpins followed two-state folding dynamics with a closing rate enhanced by 4-fold and the opening rate decreasing 2-fold for only modest concentrations of PEG. Molecular crowding agents induced a spontaneous denaturing of single protein molecules, which has been elusive for analysis in ensemble-averaged measurements.

Single-molecule force spectroscopy has an added advantage because it allows the selective manipulation at the site of interest. Force is involved in several biological processes varying from DNA segregation to cellular motility. Its magnitude can vary from the sub-piconewton to nanonewton force range. With the technical improvement in detectors, it is now possible to measure low force (∼sub-piconewton) and displacement (sub-nanometer) generated in single protein molecules or cells. Single-molecule force spectroscopy includes mainly optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers, and atomic force microscopy (AFM) and microneedle manipulation. They differ not only in instrumentation but also in force range (pN) and spatial and temporal resolution as described in ref (1). The choice of technique is dependent on the type of measurement and the information desired. The magnitude of force generated from optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers, and AFM is sufficient to unfold single proteins and nucleic acid structures. In addition to instrumental resolution, the data quality largely depends on the sample preparation conditions. Temperature variations, air circulation from coolers, air conditioners, or fans, vibrations, and electrical noise can contribute to background noise. High-precision measurement requires the instruments to be housed in an acoustically isolated, temperature-controlled environment. The applications can range from single-cell manipulation to the translocation of RNA polymerase, the rupture of covalent bonds, nucleic acid folding kinetics, and the unfolding or separation of two amino acids in a protein to measure domain movements of up to 1 Å.

In the beginning, single-molecule force spectroscopy gained popularity with its application in the analysis of kinesin and myosin movements on a microtubule and actin filaments, respectively. Later, studies with nucleic acids opened the opportunity to investigate the action of nucleic acid motors that translocate DNA or RNA. In protein folding/unfolding measurements, unfolding forces allows the estimation of bond energies and the isolation of intermediate structure formed during folding of proteins and hence constructing the energy landscape. Force spectroscopy has also been extensively used to characterize the kinetics associated with protein–ligand and antigen–antibody interactions. These experiments estimate several kinetic parameters such as Kon/Koff as well as KD for binding events associated with single proteins. In some circumstances, such values when compared to values from bulk measurements provide valuable insights into protein–ligand and protein–protein interactions. Very recently, force spectroscopy has been used to study protein phase separation occurring in the cells during neurodegenerative diseases. It has been used to estimate frequency-dependent rheology and surface tension and thereby study the viscoelastic properties of protein droplets composed of the fused in sarcoma (FUS) or heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) proteins. These discussions will be taken up in detail in the later sections of this mini-review. We will briefly discuss the scope of each single-molecule technique along with some recent experiments and the conclusions achieved from them.

2. Biochemistry Associated with Assays

Single-molecule force spectroscopy and the information obtained are largely dependent on the biochemistry of sample preparation involved in the assay. The sample preparation for each of these techniques is closely related. In this section, we will provide an overview of assays. The measurement is carried out after the biomolecule is attached to the probe. In AFM-based force spectroscopy, the probe is a cantilever tip, while in optical and magnetic tweezers, it is silica beads and paramagnetic beads, respectively. A range of attachment approaches varying from nonspecific adsorption to covalent attachment are reported. In the case of AFM, nonspecific adsorption is the most commonly used attachment method. But due to the low success rates in experiments involving nonspecific adsorption, it is getting gradually replaced by covalent attachment methods.

In covalent modification protocols, the probes are modified with streptavidin or antidigoxigenin. The protein or cells surface of interest is modified with the biotin or digoxigenin. This antibody–antigen interaction assists in the attachment of the cells or proteins to the probe.1 In one of the approaches, oligonucleotides of varying base pair length are covalently modified on one end with biotin or digoxigenin and on other end with a chemical functional group such as maleimide or sulfide. These oligonucleotides are attached to the protein through the cysteine which is suitably mutated at specific sites. An alternative to thiol or maleimide oligos is the azide oligos. The azide oligoes react with the dibenzocyclooctyne-maleimide, which in turn is bound to the protein through the cysteine.2 The success of the measurement is dependent on the efficiency with which the probe is modified, and the sample is attached to it. The probe is either attached directly or via an oligonucleotide to the proteins. In some proteins, it is difficult to attach the oligoes with mutated cysteine at specific sites due to the interference from the native cysteines. Also, if the native cysteines are required for fluorescent labeling with dyes, then other oligo attachment approaches are needed. HaloTag, bacterial sortase, and unnatural amino acid-based approaches have gained popularity in overcoming this issue. The Halotag is genetically fused to N- and C-termini of the protein of interest. The oligonucleotide with biotin or digoxygenin modification then specifically binds to the binding pocket of HaloTag.3 Another approach where the native cysteine can be retained involves the use of sortase enzymes. These enzymes anchor cell surface proteins to the cell wall. In this approach, a C-terminal motif (LPXTG) on the protein is cleaved. This is followed by the formation of an amide bond with the (GGGGG) motif cross-bridge in the cell wall.4 This mechanism can be implemented for N- and C-terminal labeling of a desired protein by using different sortases. Artificial amino acids can also be used for attaching oligonucleotides to proteins. They can be genetically engineered into the protein.5 The click chemistry approach involving artificial amino acids can be used to attach the azide oligoes to the protein of interest. As discussed above, the last three approaches retain the native cysteines, which might also be essential to the protein’s activity.

3. Single-Molecule Methods

3.1. Mechanical Manipulation with Laser-Trapped Beads: Optical Tweezers (OT)

3.1.1. Instrumentation, Assay, and Scope of Application

Optical tweezers are a versatile single-molecule force spectroscopy technique. The optical trap is created when a laser beam is focused to a spot with a high numerical aperture microscope objective.6 As a Gaussian laser beam profile is used, the intensity distribution at the trapping spot yields a harmonic (i.e., quadratic) trapping potential at small deflections. The incident beam exerts a scattering force and gradient force on the trapped particle. The former pushes the bead out of focus along the direction of beam propagation while the later pulls the bead into the region of high laser intensity. When the gradient force balances the scattering force, the bead gets trapped and is slightly behind the laser focus along the direction of beam propagation. The force acting on the bead arises due to the transfer of momentum from either reflected or refracted light. The force is linearly proportional to the displacement of the trapped object from its equilibrium position. Thus, the optical trap acts like a spring. The stiffness of the trap is dependent on how tightly a laser is focused. This is controlled by the power of the laser, the trapped object polarizability, and the numerical aperture of the objective. The trapped particle can vary from the nanometer to micrometer size range. Once trapped, the object can be manipulated to investigate its mechanical properties such as rigidity and response to stimuli. In the following section, we will briefly discuss some applications of OT to study the mechanical properties of proteins.

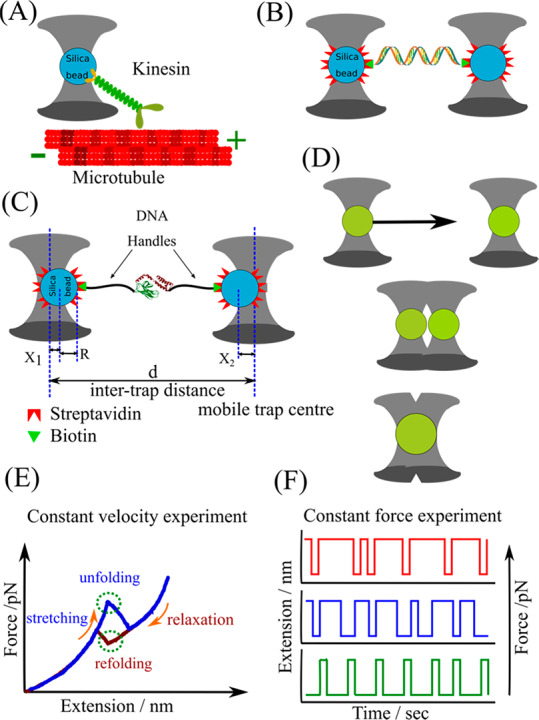

Studying a biomolecule using an OT will largely depend on its stability to laser exposure. Optical traps are suitable in the low to intermediate force regimes (0.5–65 pN). Dual trap optical tweezers (Figure 1B,C) with differential position detection provide low drift and sub-nanometer resolution. The early assays estimated the force and the displacement of optically trapped kinesin-coated beads which move along the microtubules as represented in Figure 1A.7 Similarly, virus-coated beads were used to study their interaction with the erythrocytes in the presence and absence of sialic acid-bearing inhibitor. The best inhibitor which could prevent the attachment of influenza virus to erythrocytes was identified. In another experiment, force was applied to a bead using one trap while the other trap was used to scan along the microtubule. This study explained how small tubulin oligomers directly add to growing microtubules and contribute to microtubule assembly dynamics. It further highlighted the role of microtubule end-binding proteins in regulating the microtubule dynamics in living cells. Similarly, OT assay were suitably designed to provide a mechanistic explanation of how RNA polymerase transcribed DNA. RNA polymerase was immobilized on a bead, and its movement was monitored using the optical trap as it reeled the transcribed DNA. This experiment estimated the stall force and transcriptional pausing as RNA polymerase molecules transcribe DNA. In another related assay, a bead functionalized with RNA polymerase was held in one trap and the free end of a DNA was linked to another bead in the other trap.8 Similarly, two DNA molecules were attached between two pairs of trapped silica beads, followed by bridging with a bacterial DNA histone-like nucleoid structuring protein H-NS. The DNA bridging mechanism was analyzed by pulling the DNA molecules apart with an unzipping or shearing force. Thus, the OT assays could not only be used to manipulate a single DNA molecule but also could provide information on recombination and strand-exchange phenomena.9

Figure 1.

Schematics representing optical tweezers (OT)-based assays. (A) The assay involves bringing a trapped silica bead coated with kinesin motor molecules (green) to the microtubule attached to the surface of a trapping chamber. The force and displacement generated by kinesin as it traverses along the microtubule are determined from the displacement of the bead in the optical trap. (B) One end of a nucleic acid tether is attached to a silica bead trapped at the focus of an infrared laser, while the other end is attached to another similarly optically trapped bead to generate a so-called dumbbell assay. The other bead can also be held in a micropipette tip. (C) OT assay to study the unfolding/refolding of a protein. The intertrap distance d and X1, X2 represent the deflection of each bead out of their respective trap center. With R being the bead’s radius, the extension of a stretched tether comprising DNA handles and protein is Xtether = d – 2R – X1 – X2. With calibrated trap stiffnesses k1 and k2, the force acting on the system is F = k1X1 = k2X2 = keff (X1 + X2), where keff = (1/k1 + 1/k2)−1 is the effective spring constant. (D) Experimental scheme of investigating protein droplet fusion. One laser beam is used to hold one protein droplet at a fixed position, while another protein droplet, trapped by a second laser, is moved toward the first droplet at a constant velocity. As these droplets are brought into close proximity, protein droplets coalesced rapidly (adapted and modified from ref (19)). (E) Representative constant-velocity trajectory showing a two-state unfolding/refolding event. (F) Extension–time trajectories at three constant mean forces showing a molecule fluctuating between two states.

OTs have also been used extensively to study the protein folding/unfolding (Figure 1C) and provide valuable insights into the protein energy landscape. High temporal resolution allows the identification of the short-lived previously undetected intermediate states involved during the unfolding and refolding of proteins.10 Force-induced experiments supported the existence of a mechanically stable folded core in the proteins that unfolds last and refolds first. The refolding measurements suggested the formation of distinct misfolded states after stable core formation. Thus, the OT studies concluded that the partially folded intermediates are a crucial factor governing native and non-native folding.11 The results also explained the propensity of different proteins for prion-like misfolding.11 Woodside and co-workers used an OT assay to collect the time statistics taken while crossing the transition path during the folding of a single nucleic acid and protein. The shape of the distribution was in good agreement with the theoretical one-dimensional diffusion over the landscape. Often the folding of proteins is assisted by the chaperones. The OT assay explained the chaperone action by identifying the intermediates generated during chaperone action and how chaperones block the formation of a stable misfolded states by interfering with intermolecular interactions.12 Knotted proteins form an interesting protein entity where the folding of protein involves the threading of the polypeptide chains through the peptide backbone.13 Constant velocity unfolding/refolding experiments using a dual-trap OT indicated that knotting is a fairly complicated phenomenon and generates several misfolded states. The study estimated the rate constant and folding time required to generate a knot. The high spatial resolution in the dual trap configuration allowed the detection of sub-nanometer displacements associated with the conformational dynamics of the proteins.14 Bustamante and co-workers studied hairpin loops from the Tetrahymena thermophila group I ribozyme. They unveiled unfolding and refolding kinetics and hence proposed the folding energy landscape of multiple hairpin structures.15 The enhanced resolution obtained with the above assay encouraged its application to measure and hence understand the mechanism by which hepatitis C virus RNA helicase NS3 acts on the RNA hairpin structure.15

The disordered proteins, viz., P granule proteins LAF-1, PGL-3, and MEG, nucleolar protein Fib1, and stress granule proteins FUS, TDP-43, and hnRNPA1 form membraneless organelles. The stress granule proteins are involved in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) where they exist in fibrous form, while the RNA binding proteins have been linked to neurodegenerative disease. Probing the material properties of these phase-separated protein droplets is crucial in relating the importance of phase separation in pathology and its prospective application in therapeutics. Recently, optical tweezers assays have been used to manipulate and study protein-droplet dynamics (Figure 1D). This has allowed researchers to unravel the fundamental processes involved in phase separation. Two trapped polystyrene beads were brought into close adhesive contact with a fluorescently labeled protein droplet. After the beads were in contact, one of the beads was manipulated to move along an axis in order to probe the microrheological properties of the droplet.16 Jawerth et al. found that the viscosity and surface tension of the protein droplet can be modulated by varying the salt concentrations.16 Thus, the electrostatic interactions vary in a concentration-dependent manner to influence the material properties of protein droplets. Using OT and other biochemical assays, Alshareedah et al. reported that K/G-rich peptides complexing with poly(U) fused twice as fast as R/G-rich peptides complexing with poly(A) RNA. The results indicated a higher fluidity and lower viscosity in the former, suggesting that short-range attractions and long-range forces regulate the dynamics of RNA–peptide condensate formation, including coalescence and rigidity.17

3.1.2. Limitations

The stability of the laser used in the OT setup is critical for trapping, and any fluctuations in laser intensity can lead to drift problems. Thus, the trap stiffness and hence the force acting on the biomolecule are no longer the same. The constant force measurements are erroneous under this condition. Sample purity is also critical because any free-floating dielectric particle near the focus can get trapped and interfere with the trapping of the silica beads. This makes experiments involving cell extracts extremely challenging. The high-intensity laser used for optical trapping results in local heating, causing enzyme degradation and an alteration of the viscosity of the solution. Heating effects can also result in temperature gradients and convection currents in solution which adversely affect the measurements. There have been efforts to estimate the temperature in the vicinity of the trap.18 Reactive oxygen species are generated by the lasers used for optical trapping, which adversely affects the mechanical stability of the protein tethers. However, this damage is minimized by introducing an enzymatic scavenging system consisting of glucose oxidase, catalase, and glucose. Data treatment involves careful analysis of the instrument signal and treatment of the bead calibration signal.18 The one-dimensional approach in OT fails to provide a three-dimensional picture of cells. The trapping laser can also damage biological samples, which restricts their feasibility for in vivo applications. Noninvasive manipulation of a cell and its organelles remains a challenge with conventional OT. The setup requires technical modification to overcome this difficulty, and some of the approaches are briefly discussed in the following section.

Conventional OT has a small working distance which makes experiments with turbid samples (viz., cell lysates) difficult. Fiber-based optical trapping (OFT) serves as an excellent alternative where two counter-propagating beams from two pigtailed optical sources generate the tweezing effect. Their trapping and manipulating capabilities depend on the optical and geometrical features of the fiber tip and the fabrication technique used to design it. Specially fabricated OFTs exhibited 2D trapping of yeast cells and also manipulated the internal organelles of Medicago Sativa cells without damaging them.

Plasmonic optical tweezers (POT) and photonic crystal optical tweezers (PhCOT) utilize localized surface plasmons to generate optical traps with large stiffness. This reduced the Brownian motion of the trapped object and improved the particle positioning. Large trapping forces were achieved with low laser powers which allowed the nanomanipulation of biological samples, viz., elongated cells of E. coli bacteria. Trapped NIH/3T3 mammalian fibroblasts and E. coli were sustained for more than 30 min. A local temperature rise of <0.3 K minimized photodamage. These POTs also trapped a single bovine serum albumin (BSA). Thus, plasmon-based traps have great potential for various biomedical applications.19

Femtosecond optical tweezers (fsOTs) based on a femtosecond laser source with high peak power but short pulse duration prevent the mode-locked laser oscillators from generating a population inversion at high energies. It limits the pulse energy to a few nanojoules (nJ). This feature makes them a noninvasive tool for the manipulation of cells, viz., trapping human red blood cells and rotating them inside the trap by modulating the laser light intensity.19

With the above technical advancements, although some of the major limitations of OTs are resolved, there are still scopes for improvement depending on the biological question we wish to address.

3.2. Mechanical Manipulation with Magnetically Trapped Beads: Magnetic Tweezers (MTs)

3.2.1. Instrumentation, Assay, and Scope of Application

Magnetic tweezers are another commonly used single-molecule force spectroscopy technique. It is based on a pair of magnets or electromagnets capable of rotating a magnetic particle having a size of ≤5 μm. These magnets generate the required torque on the magnetic particle. The force experienced by the biomolecule is dependent on the magnetic field gradient.20 The magnetic field generates a magnetic moment in the superparamagnetic bead which experiences a force in the direction of the field gradient.20 Higher forces (∼200 pN) are achieved with steep field gradients using micrometer-sized beads. A particle experiences a higher force when it is close to the magnet, and it decreases as we move away from the magnet. With MT, it is possible to monitor small length scale movements. Larger magnets generate stronger magnetic fields and a shallow field gradient.

Superparamagnetic beads used in the MT assays are commercially available from several manufacturers such as Dynal/Invitrogen and Bangs Laboratories with a variety of chemical modifications. The chemical modifications and storage conditions prevent the beads from aggregating. These beads have an embedded magnetic particle (∼10–20 nm) in a porous matrix sphere, with the polymer shell finally covering it. The magnetic field orients the domains in the particle and results in a magnetic moment directed along the magnetic field. Therefore, under the influence of a magnetic field, a torque acts on the bead which orients its axis in the field direction. The bead undergoes rotation when the field acting on it is rotated. The magnitude of stiffness achieved using the proposed arrangements is ∼10–6 pN nm–1, which allows passive force clamp experiments.

Constant force experiments with optical tweezers require sophisticated active feedback. Such measurements with magnetic tweezers are free from drift and noise. However, the permanent magnet in the tweezers cannot be used to directly manipulate magnetic particles. The beads are attached to the sample chamber using DNA molecule. The magnets are aligned above the sample chamber placed on an inverted microscope, which generates a force on the beads directed vertically upward as described in Figure 2A. Reference (20) provides a detailed overview of the magnetic tweezers instrumentation and critical factors influencing its performance. The drift problem is corrected by comparison with a reference bead immobilized on the sample chamber. Force is calibrated using a variance-based equipartition method.20 Forces in excess of 20 pN can be achieved using sample chambers having an approximate thickness of 100 μm and beads of 1 μm diameter. In electromagnets, the magnitude of current governs the force and extent of bead rotation. In some electromagnetic setups, high current generates considerable heat, which requires the use of cooling systems. Electromagnetic tweezers can apply pulling forces of up to a few tens of nanonewton (nN) on a magnetic bead of size ≤5 μm and located ∼10 μm from the magnets.20 This setup has reduced vibration and grants faster control over the magnetic field, which finally generates an efficient feedback loop to provide a stable force clamp.

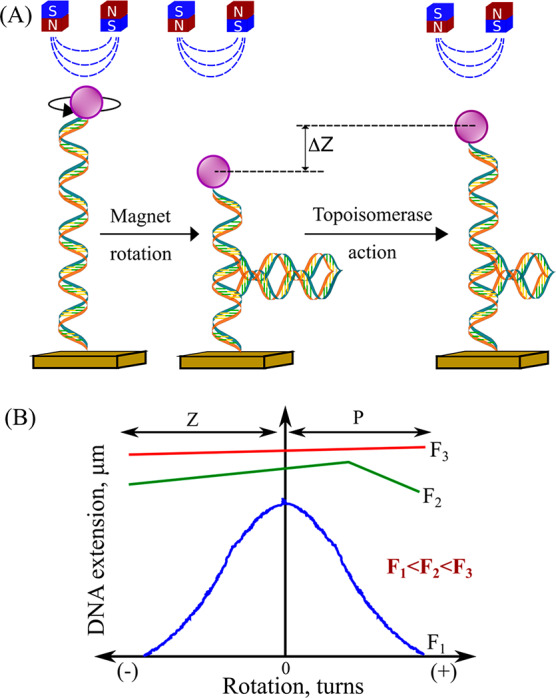

Figure 2.

(A) In magnetic tweezers (MTs), a magnetic field acts in a direction perpendicular to the DNA axis, which limits the angular rotations of the bead while exerting an upward pulling force. Rotating the magnets will introduce a torque. When torque buildup is greater than the bucking torque, coiled structures form that lead to the bead being pulled toward the substrate. Topoisomerase action relaxes the supercoil in the DNA, leading to changes in the bead height, with ΔZ being proportional to the number of supercoils removed. (B) Representative hat curves for a bead with an attached DNA. At low force, the hat curves are symmetric. At higher forces, untwisting causes DNA melting or the formation of Z-DNA, whereas overtwisting induces the formation of P-DNA, which suppresses the formation of supercoils and the resulting DNA contraction.

Sample damage by heating and photodamage is considerably eliminated with magnetic tweezers. It is not highly sensitive to sample and sample chamber preparation but depends on the magnetic bead quality. These advantages allow measurement within the cells.

Magnetic tweezers have been used to study the topology of DNA and the mechanism of topoisomerases action.20 DNA is connected to the sample chamber and the beads through biochemical approaches described previously. Rotation of the magnets leads to the spinning of the beads, which created coils in the DNA structure as represented in Figure 2. Using the MT assay, it was concluded that type IB topoisomerase releases the supercoils in DNA through multiple steps via a mechanism involving friction between rotating DNA and the enzyme cavity.20 It is also dependent on the torque stored in the DNA. In another similar study, Eeftens et al. employed MT to measure the packing of DNA molecules by the budding yeast condensin complex.21 The condensin performs its action in two distinct steps. Before ATP hydrolysis, in the beginning, condensin gets attached to DNA through electrostatic interactions. This encircles the DNA in a ring-like structure initiating DNA compaction. These binding patterns are crucial to unraveling the phenomenon of DNA compaction and hence the chromosome compaction. Similarly, topoisomerase IB bound to camptothecin was used to study the effects of antitumor chemotherapy agents on supercoil relaxation.20

The MTs were also used to study unfolding/refolding in proteins. In some recent reports, the MT assay was extended to sub-piconewton-level forces, and it was also possible to carry out drift-free constant force measurements. Unfolding and refolding experiments were carried out on small, single-domain protein ddFLN4 and large, multidomain dimeric protein von Willebrand factor (VWF). It was revealed that the rates of these processes vary exponentially with force.22 Using the MT and slightly modifying the biochemistry, Achim et al. could resolve how the Ca2+ ions mediate to stabilize the A2 domain of VWF. They noticed that the transitions originating from the effect of force are primarily observed in the low force regime.

3.2.2. Limitations

The large magnitude of torque generated by the magnetic field is sometimes difficult to measure on the magnetic tweezers setup. Also, the performance of the MTs is best judged by its resolution which is dependent on signal detection capabilities. The video-based detection limits the sensitivity and makes very fast or very small structural reorientation difficult to discover. However, the inclusion of CMOS cameras, graphics processor unit (GPU) computation, and bright coherent laser source for illumination have enabled the observation of biological events on sub-millisecond time scales with sub-nanometer resolution. In electromagnetic tweezers, magnetic field parameters such as strength and direction can be modulated by the electric current. For constant force measurements, stable force clamps are needed which requires efficient feedback loops and customized pole pieces. However, the major drawback lies in integrating the electromagnet into tweezers. Also, a cooling system should be incorporated to reduce the heat generated from the large magnetic field and field gradient. Additionally, it is difficult to handle samples that are sensitive to magnetic fields. Thus, metalloproteins are difficult to study with magnetic tweezers. The large magnetic poles placed near the sample make it cumbersome to combine with other spectroscopic setups. Nevertheless, these limitations mostly restrict the sample selection, but the potential of applications is improving through continuous technical development.

3.3. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

3.3.1. Instrumentation, Assay, and Scope of Application

AFM is extensively used to study the surface topography of modified surfaces such as silicon wafer surfaces and lipid bilayers at sub-nanometer resolution. There are three modes of measurement, namely, contact mode, noncontact mode, and tapping mode. Their use depends on the desired information. The mechanical manipulation of single protein molecules makes AFM an ideal tool for protein folding/unfolding applications. It also has the advantage of allowing measurements to be made under nearly physiological conditions. It can resolve forces of up to a few piconewtons. In force spectroscopy experiments, the cantilever moves vertically toward the specimen plane.23 High-resolution force–extension curves in AFM are achieved using piezoelectric actuators and a capacitor or a linear voltage differential transformer. The actuator controls the vertical motion, while the later monitors the displacement of the cantilever.

Cantilever material and its shape are critical parameters that govern its stiffness. Force is calculated using the spring constant of the bending cantilever. The stiffness value ranges from 10 to 105 pN nm–1. The cantilever needs to calibrated accurately prior to use. The extension arising from the stretching of protein is calculated from the variation in distance of the handles attached to the protein of interest. Incorporating a closed-loop position feedback and use of piezoelectric stages helps in achieving drift-free data with angstrom-level resolution. The data must be carefully analyzed to account for the cantilever deflection.

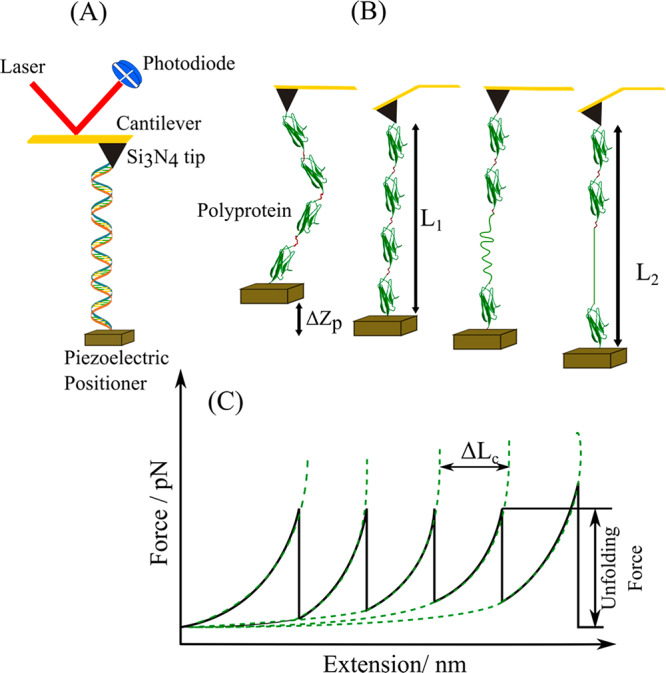

The success of the force extension measurement depends on the efficiency with which the protein is connected between the sample chamber and the cantilever. The cantilever and the substrate surface are treated chemically to form specific bonds with the protein. If the biomolecule is nonspecifically adsorbed to the substrate surface, then the attachment is unstable and can lead to erroneous characterization. The attachment of biomolecules to the surfaces can also be accomplished by using the biochemical methods described previously, but in the presence of reducing agents, some of these approaches are difficult. It can also lead to multiple molecules being attached between the cantilever and the surface as the surface area of the cantilever is comparatively larger than the protein under investigation. This problem is avoided by using low concentrations of sample. Usually a DNA or an oligomer of Titin I27 domains is conjugated to the protein molecule under study. On stretching a bare DNA as shown in Figure 3A, it melts at 65 pN.23 The presence of a transition at 65 pN in stretching curves is an indication of a single molecule between the cantilever and surface. Similarly, when a I27 oligomer is unfolded, a characteristic sawtooth pattern such as that shown in Figure 3C is observed. The presence of this characteristic pattern in the I27 oligomer attached protein indicates the stretching of a single protein molecule.23 Antibody-functionalized AFM tips also provide similar specificity.

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic representing an atomic force microscope. A DNA molecule is attached to the substrate on the piezoelectric stage and the cantilever tip. As the piezoelectric stage is retracted along the axial direction, the separation between the cantilever and the sample surface increases. The cantilever deflection generates a force acting on the DNA. The extension of DNA is calculated from the distance between the AFM tip and the substrate. (B) AFM measurements of a polyprotein construct. The movement of the piezoelectric positioner is represented by ΔZp. Initially the protein is in a relaxed state. Stretching this protein to near its folded contour length, L1, requires a force that is measured as a deflection of the cantilever. Stretching further increases the applied force, which triggers the unfolding of a domain, increasing the contour length of the protein and relaxing the cantilever back to its resting position. Further stretching removes the slack and brings the protein to its new contour length L2 (adapted and modified from ref (23)). (C) Characteristic force–extension sawtooth pattern curve resulting from stretching a polyprotein. Each sawtooth peak corresponds to the unfolding of one of the domains, while the last peak arises from the detachment of the molecule from the substrate or AFM tip. The amplitude of the sawtooth unfolding force peak measures the force at which the protein domain unfolds. Dotted lines correspond to fits of the worm-like chain model of polymer elasticity to the experimental data. The contour length increment, ΔLc, measures the length increment upon protein unfolding.

The force–extension curves of proteins highlight the mechanical stability and structural intermediates involved in the unfolding/folding of protein. During the measurement, the cantilever tip is lowered to the surface or the piezoelectric actuators raise the surface toward the cantilever tip as represented in Figure 3B. This brings the sample on the surface and the cantilever tip in close contact. Once a tether is formed, the retraction of the tip from the surface causes its bending. Using the stiffness of the cantilever and the extension obtained from AFM, the force is finally calculated from Hooke’s law. The nonlinear force extension curve is analyzed using a worm-like chain (WLC) model as represented in Figure 3C. This analysis yields the persistence length and contour length of the unfolded proteins.

Force spectroscopy using AFM has been used to study the rupture of bonds and the mechanical stability of proteins and nucleic acids via unfolding/refolding.23 Mechanical unfolding of filamin protein led to the discovery of unfolding intermediates. When the pulling direction in proteins was changed, rupture forces and unfolding pathways varied significantly.23 This was carried out by mutating a pair of cysteines at the point of application of force and attaching the protein to surfaces using specific protocols. Force-clamp spectroscopy using AFM allows us to investigate the result of force-induced conformational changes on enzymatic functionality. For this study, a cysteine was engineered in a polypeptide chain. Following this, AFM was used to measure the variation in the rate of disulfide reduction as a function of force. Similarly, kinase domains of titin are force-sensitive. On application of force, it unfolded in a stepwise pattern. Membrane protein bacteriorhodopsin was localized and extracted from the purple membrane patches in Halobacterium salinarum. The force required for extraction varied between 100 and 200 pN. At these forces, protein helices begin to unfold. The unfolding patterns in the force spectra led to the classification of the unfolding pathway.24 When single-molecule AFM imaging (lateral resolution 0.5–1 nm and vertical resolution 0.1–0.2 nm) was coupled with force spectroscopy, it offered valuable insight into the interactions between individual bacteriorhodopsin molecules and the purple membranes and between secondary structure elements within bacteriorhodopsin. The force sensitivity and time response of the AFM force measurement depend on the design of the AFM microcantilever. Short cantilevers of ∼20–30 μm were fabricated using a focused ion beam, and the reflective gold layer was removed.24 This cantilever was used to study the mechanical unfolding of bacteriorhodopsin. The data revealed smaller unfolding intermediates which rapidly switched between unfolding and refolding with lifetimes of <10 μs. Equilibrium measurements between such states deduced the folding free-energy landscape. Also, a previously undetected retinal stabilized state in the unfolding pathway of bacteriorhodopsin was identified. Thus, the new cantilever design improved the response time to microsecond time resolution and increased the force sensitivity by a factor of ∼10. It could resolve the unfolding/refolding of two to three amino acids. Similarly, an AFM was used to study a small RNA hairpin from HIV which is involved in stimulating programmed ribosomal frameshifting. It resulted in estimations of kinetic parameters such as rate constants at zero force and distances to the transition state. This information was further utilized to construct a folding free-energy landscape for an RNA hairpin.24

Additionally, AFM measurement provides insight into the forces, energetics, and kinetics of cell-adhesion processes. It has been used to characterize how cells respond to mechanical stress upon ligand binding. AFM was used to measure the adhesion force at which fibroblasts start detaching from fibronectin and the rupture forces at which single integrins unbind ligand.25 During adhesion initiation, fibroblasts respond to forces by strengthening integrin-mediated adhesion to fibronectin. α5β1 integrins form catch bonds with fibronectin and signal the fibronectin-binding integrins to reinforce cell adhesion.

3.3.2. Limitations

Due to the high stiffness of the AFM cantilever, it is suitable for applications in the high force regime. Thus, AFM is incompatible for studying small domain movements or conformational changes. Small unfolding in subdomains of a multidomain protein cannot be resolved using AFM due to a poor signal-to-noise ratio. It is expected that the cantilever design proposed by Perkin and co-workers will succeed in solving this issue. Due to poor specificity of the cantilever tip, it can be difficult to differentiate interactions of the tip with the molecule of interest from nonspecific interactions or inappropriate contacts with the molecule of interest. Inappropriate contacts will decrease the strength of the bonding, and thus the tethers tend to rupture at low forces. This reduces the success rate of the measurements.

4. Prospects and Outlook

Improvement in the instrumentation has extended the scope of application. Also, simplifying the instrumentation and its handling allows it to be more appreciated by biologists in addition to biophysicists. The key challenge lies in performing in vivo measurements by taking the probe into the interior of cells without damaging the cells. This will provide valuable information on how enzymes function under cellular conditions and how cells create and respond to forces. But recording the desired signal in the presence of high background noise arising from the inhomogeneous environment needs to addressed. FsOT and OFT have successfully accomplished the in vivo measurements. The implementation of microfluidics has contributed significantly to understanding the function of macromolecular protein machines and multienzyme complexes. Also, coupling different single-molecule techniques will allow us to address complex biological questions. A time-shared ultra-high-resolution dual optical trap interlaced with a confocal fluorescence microscope could explain how individual single-fluorophore-labeled DNA oligonucleotides bind and unbind complementary DNA.19 The combined setup allowed single-fluorophore detection and angstrom-scale extensions simultaneously. To enable the parallel manipulation and visualization of biomolecular interactions in real time, a high-resolution OT coupled with fluorescence, label-free microscopy, and an advanced microfluidics system known as a C-trap is commercially manufactured by LUMICKS. Additionally, increasing the throughputs will encourage more biochemists to adopt force spectroscopy. A novel near-field optical trapping device (nanophotonic standing wave array trap, nSWAT) combines manipulation, microelectronics, and microfluidics. High-precision position and velocity control is achieved using a standing wave mechanism and thermooptic phase modulators. This enables on-chip implementation of single-molecule experiments on parallel arrays of molecules.19 Similarly, in acoustic force spectroscopy (AFS, LUMICKS), resonant acoustic waves are used to stretch multiple biomolecules individually tethered between a surface and micrometer-sized particles with a density different from that of the surrounding medium. Thus, new technologies will greatly contribute to improving the signal quality and detection capabilities of novel single-molecule force spectroscopy techniques, which will enhance the scope of applications.

Acknowledgments

The author is thankful to the Science and Engineering Research Board, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, for an Early Career Research Award (ECR/2018/001929).

Biography

Soumit S. Mandal completed his integrated Ph.D. in chemical sciences in the Solid State and Structural Chemistry Unit, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India in 2013. Later, he moved to Germany and started his postdoctoral research career in the Physics Department of the Technical University of Munich. He is the recipient of a TUM University Foundation Fellowship (TUFF) by the Technical University of Munich and Humboldt Fellowship for postdoctoral research by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. He is currently an assistant professor in the Chemistry Department, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Tirupati, India.

The author declares no competing financial interest.

References

- Neuman K. C.; Nagy A. Single-molecule force spectroscopy: optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers and atomic force microscopy. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 491–505. 10.1038/nmeth.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhortava A.; Schlierf M. Efficient Formation of Site-Specific Protein–DNA Hybrids Using Copper-Free Click Chemistry. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016, 27, 1559–1563. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los G. V.; Encell L. P.; McDougall M. G.; Hartzell D. D.; Karassina N.; Zimprich C.; Wood M. G.; Learish R.; Ohana R. F.; Urh M.; Simpson D.; Mendez J.; Zimmerman K.; Otto P.; Vidugiris G.; Zhu J.; Darzins A.; Klaubert D. H.; Bulleit R. F.; Wood K. V. HaloTag: A novel protein labelling technology for cell imaging and protein analysis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008, 3, 373–382. 10.1021/cb800025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proft T. Sortase-mediated protein ligation: an emerging biotechnology tool for protein modification and immobilisation. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010, 32, 1–10. 10.1007/s10529-009-0116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noren C. J.; Anthony-Cahill S. J.; Griffith M. C.; Schultz P. G. A general method for site-specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids into proteins. Science 1989, 244, 182–188. 10.1126/science.2649980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkin A.; Dziedzic J. M.; Bjorkholm J. E.; Chu S. Observation of a single-beam gradient force optical trap for dielectric particles. Opt. Lett. 1986, 11, 288. 10.1364/OL.11.000288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda K.; Schmidt C. F.; Schnapp B. J.; Block S. M. Direct observation of kinesin stepping by optical trapping interferometry. Nature 1993, 365, 721–727. 10.1038/365721a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson M. H.; Landick R.; Block S. M. Single-molecule studies of RNA polymerase: one singular sensation, every little step it takes. Mol. Cell 2011, 41, 249–262. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugesapillai D.; McCauley M. J.; Maher L. J. III; Williams M. C. Single-molecule studies of high-mobility group B architectural DNA bending proteins. Biophys. Rev. 2017, 9, 17–40. 10.1007/s12551-016-0236-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stigler J.; Ziegler F.; Gieseke A.; Gebhardt J. C.; Rief M. The complex folding network of single calmodulin molecules. Science 2011, 334, 512–516. 10.1126/science.1207598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer N. Q.; Woodside M. T. Probing microscopic conformational dynamics in folding reactions by measuring transition paths. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 53, 68–74. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashaghi A.; Bezrukavnikov S.; Minde D. P.; Wentink A. S.; Kityk R.; Zachmann-Brand B.; Mayer M. P.; Kramer G.; Bukau B.; Tans S. J. Alternative modes of client binding enable functional plasticity of Hsp70. Nature 2016, 539, 448–451. 10.1038/nature20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler F.; Lim N. C.; Mandal S. S.; Pelz B.; Ng W. P.; Schlierf M.; Jackson S. E.; Rief M. Knotting and unknotting of a protein in single molecule experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 7533–7538. 10.1073/pnas.1600614113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelz B.; Žoldák G.; Zeller F.; Zacharias M.; Rief M. Subnanometre enzyme mechanics probed by single-molecule force spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10848. 10.1038/ncomms10848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangkulwanich M.; Ishibashi T.; Bintu L.; Bustamante C. Molecular mechanisms of transcription through single-molecule experiments. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3203–3223. 10.1021/cr400730x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawerth L. M.; Ijavi M.; Ruer M.; Saha S.; Jahnel M.; Hyman A. A.; Jülicher F.; Fischer-Friedrich E. Salt-Dependent Rheology and Surface Tension of Protein Condensates Using Optical Traps. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 258101. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.258101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshareedah I.; Kaur T.; Ngo J.; Seppala H.; Kounatse L. D.; Wang W.; Moosa M. M.; Banerjee P. R. Interplay between Short-Range Attraction and Long-Range Repulsion Controls Reentrant Liquid Condensation of Ribonucleoprotein-RNA Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 14593–14602. 10.1021/jacs.9b03689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennerich A., Ed.; Optical Tweezers, Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, 2017; Vol. 1486. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary D.; Mossa A.; Jadhav M.; Cecconi C. Bio-Molecular Applications of Recent Developments in Optical Tweezers. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 23. 10.3390/biom9010023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipfert J.; van Oene M. M.; Lee M.; Pedaci F.; Dekker N. H. Torque spectroscopy for the study of rotary motion in biological systems. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 1449–1474. 10.1021/cr500119k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeftens J.; Dekker C. Catching DNA with hoops-biophysical approaches to clarify the mechanism of SMC proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 1012–1020. 10.1038/nsmb.3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löf A.; Walker P. U.; Sedlak S. M.; Gruber S.; Obser T.; Brehm M. A.; Benoit M.; Lipfert J. Multiplexed protein force spectroscopy reveals equilibrium protein folding dynamics and the low-force response of von Willebrand factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 18798–18807. 10.1073/pnas.1901794116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann T.; Dougan L. Single molecule force spectroscopy using polyproteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4781–4796. 10.1039/c2cs35033e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards D. T.; Perkins T. T. Optimizing force spectroscopy by modifying commercial cantilevers: Improved stability, precision, and temporal resolution. J. Struct. Biol. 2017, 197, 13–25. 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg M.; Fläschner G.; Alsteens D.; Gaub B. M.; Roos W. H.; Wuite G. J. L.; Gaub H. E.; Gerber C.; Dufrêne Y. F.; Müller D. J. Atomic force microscopy-based mechanobiology. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2019, 1, 41–57. 10.1038/s42254-018-0001-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]