Abstract

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome is a rare disease with a classic triad of port wine stains, varicose veins, and bony and soft tissue hypertrophy of an extremity. The quality of life in these patients is significantly affected, making the prenatal diagnosis of Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome important. We present four prenatally diagnosed cases of this anomaly with a unique case of ectrodactyly of the hand in foetus with Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. Such a combination has not been previously reported prenatally. A review of the literature for similar cases is also presented.

Keywords: Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, prenatal diagnosis, ectrodactyly, prognosis, outcome

Introduction

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS, OMIM 149000) is a rare disease, characterised by a classic triad of port wine stains, varicose veins, and bony and soft tissue hypertrophy of an extremity.1 Other anomalies reported include cavernous haemangiomas, which may involve any region of the body (particularly limbs and trunk) and any organ (especially the lungs, large bowel, bladder and liver). Anomalies of digits and visceromegaly also are seen. The aetiology of the disease remains unknown. In most cases, it occurs sporadically without sex predilection. The prognosis of KTS is usually favourable, but the quality of life is significantly affected.2 Prenatal diagnosis of this syndrome allows timely determination of the place of delivery and the anticipation of appropriate medical care for the newborn or provide the family the opportunity to decide whether to continue the pregnancy. In this report, we described four cases of the KTS, diagnosed prenatally at different gestational ages. A review of the literature for similar cases is also presented.

Material and methods

This was a retrospective review of cases of KTS detected prenatally by ultrasound from the Medical Genetic Department of Moscow Regional Research Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology between 2010 and 2017. All cases are presented with the written informed consent of patients. The research was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Institute.

The US-scans were performed using WS80A (Samsung Medison, Korea, probes CV1-8A, E3-12A) and Voluson E8 (GE Medical Systems, USA, probes RAB4-8-D, IC5-9-D) US-machines. Cases 1 and 4 were scanned by OI (WS80A), Case 2 by EA (Voluson E8), Case 3 by NO (WS80A, first exam) and EA (Voluson E8, second and third exams).

Prenatal diagnosis of KTS was based on the sonographic detection of superficial multiple cystic structures spreading over limb and body, with hemihypertrophy of the affected limb. The colour Doppler ultrasound was used to assess the presence and intensity of blood flow signals within the lesions and/or presence of arteriovenous fistulae. A thorough examination was performed to reveal the distribution of the masses, presence of the vascular anomalies inside the affected limb or cystic lesions of internal organs. Particular attention was paid to the assessment of the skeletal system (equal length of the long bones in the arms and legs; presence of the hand/foot defects or spine/ribs anomalies).

All patients were counselled by multidisciplinary team which included US-specialist, geneticist, paediatric surgeon and obstetrician. Prognosis for the foetus was determined depending on the gestational age at the time of the diagnosis, the extent of the lesions, internal organs involvement, vascularisation degree and the progression rate of haemangiomas. In all our cases, there were no lesions with high vascularisation. Nevertheless, prognosis was defined as poor due to early onset of the symptoms, marked lesions of the limb and trunk (Cases 1, 4) and due to negative progression (Case 3). In Case 2, cystic lesions appeared in the third trimester and involved only buttock and thigh. But prognosis for this baby was determined as guarded due to the possibility of the variable post-partum complications including the consumption coagulopathy.

Information on maternal demographics, sonographic features, subsequent antenatal management and perinatal outcome was obtained by reviewing the ultrasound images and medical records of the patients.

An extensive review of the literature was performed through a computerised search of the Pubmed/MEDLINE database and TheFetus.net web-site using key words “Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome”, “Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome”, “h(a)emangioma”, “h(a)emangioendothelioma”, “h(a)emangiolymphangioma” with “fetal”, “fetus” and “prenatal diagnosis” without limits of time.

Results

A total of four cases of KTS were identified (Table 1). The median maternal age was 29 years (range 21–36). All our patients had no history of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy or preterm birth. Family and medical history was unremarkable in all cases. The median gestational age at diagnosis was 24 weeks (range 20–32).

Table 1.

Prenatal detection of KTW syndrome: Our cases and review of the literature

| GA (w/g) | Limb involvement | Hand/foot anomalies | Trunk involvement | Internal lesions | Associated US-findings | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case no./references | |||||||

| Case 1 | 20 | Left leg | – | + | + | Polyhydramnios | TOP |

| Case 2 | 32 | Left leg | Abnormal disposition of the toes | + | − | – | SD at 39 w/g 4 d/o: died due to KMS |

| Case 3 | 24 | Left leg | – | + | + | – | TOP |

| Case 4 | 20 | Right arm | Ectrodactyly of the right hand | + | + | Ascites | TOP |

| Hatjis et al.3 | 34a | Left leg, right arm | – | + | − | Polyhydramnios | SD at 36 w/g Complete resolution of lesions at 10 m/o |

| Warhit et al.4 | 32 | Left leg | – | − | − | – | CS at 39 w/g Live at 21 d/o old, observation |

| Seoud et al.5 | 16a | Left arm | – | + | Testes, adrenal glands | – | TOP |

| Lewis et al.6 | 22 | Both legs and arms | Overgrowth of the second toes of both feet. | + | Retroperitoneal space, pericardium, cataracts | – | TOP |

| Shalev et al.7 | 33 | Right leg | – | + | − | Polyhydramnios at 33 w/g | ID at 33 w/g Died at Day 4 |

| Mor et al.8 | 30a | Left leg | – | − | − | Anasarca, polyhydramnios, bulky placenta | SD at 37 w/g Port wine naevi on the arms, trunk and the left leg. 6 d/o: resolution of hydrops 6 m/o: no regression of lesions |

| Drose et al.9 | 29a | Right leg | Hypoplastic thumbs, syndactyly with hypoplastic fingernails of the both hands | − | Cataracts | Cardiomegaly, hepatomegaly, ventriculomegaly, polyhydramnios | CS at 35 w/g Died shortly after birth |

| Heydanus et al.10 | 20 | Right leg | – | + | − | Cardiomegaly | TOP |

| Hayashi et al.11 | 19a | Both legs | – | + | Retroperitoneal space | Polyhydramnios | TOP |

| Jorgenson et al.12 | 19 | Left leg | – | − | Liver | – | TOP |

| Yankowitz et al.13 | 17 | Right leg | – | − | − | Ventriculomegaly, pleural effusion | TOP |

| Meizner et al.14 | 14a | Both legs | Marked left foot hypoplasia | + | Intestine | – | TOP |

| Christenson et al.15 | 34 | Right leg | – | − | − | Cardiomegaly, thickened placenta | CS at 34 w/g KMS, intensive conservative treatment, embolisation 4 d/o: cardiovascular decompensation, amputation at the right hip 6 m/o: normal development |

| Paladini et al.16 Case 1 | 17 | Left leg | – | + | Intestine, liver, kidneys | – | TOP |

| Paladini et al.16 Case 2 | 18 | Right leg | – | + | − | Polyhydramnios, pericardial effusion | TOP |

| Roberts et al.17 | 19 | Right arm, left leg | – | + | − | 34 w/g: left-sided hydrocele | CS at 37 w/g 22 d/o: Excision of the chest wall lesion, radical axillary dissection. Conservative management of the residual lesions |

| Shih et al.18 | 15 | Left leg | – | + | − | Ventriculomegaly | TOP |

| Jeanty19 | NR | Leg | – | − | Abdomen | – | NR |

| Mejia et al.20 | 20 | Right leg | – | + | Intestine | – | SD |

| Goncalves et al.21 | 30a | Right leg | – | + | − | – | CS at 37 w/g Conservative management 9 m/o: port wine stains appeared at the right thigh and knee, no resolution of the mass, varicosities of the affected leg. Expectant management up to two years |

| Martin et al.22 | 20 | Left leg | – | + | Thorax, pelvis | Oligohydramnios, hypoplastic thorax | TOP |

| Zoppi et al.23 | 28 | Right leg | Both feet: macrodactyly, hypertrophy of the second toe; widely spaced I and II toes | + | Abdomen, pelvis, bowel, right kidney | Cardiomegaly | Emergency CS at 32 w/g Died 8 h after delivery due to KMS |

| Assimakopoulos et al.24 | 22a | Both legs | – | + | Small intestine | – | SD at 38 w/g Expectant management 13 m/o – reduction in size of abdomen lesion |

| Sahinoglu et al.25 | 24 | Left leg | – | − | − | Umbilical cord haemangioma | Preterm SD at 26 w/g Died 10 h later because of pulmonary immaturity |

| Peng et al.26 Case 1 | 28 | Left leg | – | + | Retroperitoneal space | 33 w/g: polyhydramnios | CS at 37 w/g 4 d/o: KMS, E. coli sepsis few days later 10 d/o: died |

| Peng et al.26 Case 2 | 35a | – | – | − | - | Ascites, pleural effusion, cardiomegaly | ID at 35 w/g Haemangiomas and varicosity of the right leg, vascular malformation. KMS 5 and 7 d/o: embolisation 15 d/o: died |

| Chen et al.27 | 22 | Right leg | - | + | - | Ascites, hydrocele | SD at 36 w/g 2 m/o – partial resolution of the ascites |

| Coombs et al.28 | 24 | Both legs | Hemihypertrophy, syndactyly of the right foot, left hallux hypertrophy | + | Retroperitoneal space | Hypoplasia/aplasia of the deep venous system | CS at 38 w/g 7 m/o – deep venous system anomaly, including persistent embryonal veins |

| Volkov et al.29 | 22 | Both arms | – | + | − | – | TOP |

| Al-Asali et al.30 | 22 | Both legs | Talipes equinovarus, abduction of the thumb and syndactyly of the right hand | + | − | Polyhydramnios | PD at 33 wks 14 d/o: died due to KMS |

| Horenstein31 | NR | Left leg | Hypertrophy of fingers on the both hands, syndactyly of the right hand. Left foot toes hypertrophy, syndactyly | + | Abdomen | – | SD |

| Cakiroglu et al.32 | 25 | Right leg | – | + | − | Persistent embryonic lateral marginal veins | TOP |

| Tanaka et al.33 | 24 | Left leg | – | + | Retroperitoneal space | 24 w/g: no 27 w/g: hydrops, cardiomegaly, acute foetal anaemia | Emergency CS at 27 w/g Death at 40 min after delivery due to KMS |

Note: Manifestations found only postnatally are italicised. GA: gestational age; NR: not reported; TOP: termination of pregnancy; SD: spontaneous delivery; PD: preterm delivery; ID: inducted delivery; CS: Caesarean section; KMS: Kasabach–Merritt syndrome; d/o: days old, m/o: months old; w/g: weeks' gestation.

Final diagnosis was made only after birth.

Male to female ratio was 1:3. In all our cases, there was involvement of only one limb and trunk, with bone asymmetry was excluded. The left lower limb affection was predominant one. In two cases, there were also hand/foot defects: abnormal placement of the toes and ectrodactyly of a hand. Internal organs involvement was found in three of the four foetuses. It is worth noting that in one case intraabdominal mass was the only initial US-finding, while limb hypertrophy and superficial haemangiomas appeared three weeks later.

Three patients opted to terminate the pregnancy. In the fourth case, the pregnancy ended in childbirth. Prenatal diagnosis was confirmed postnatally by the geneticist in all cases.

Our cases description

Case 1

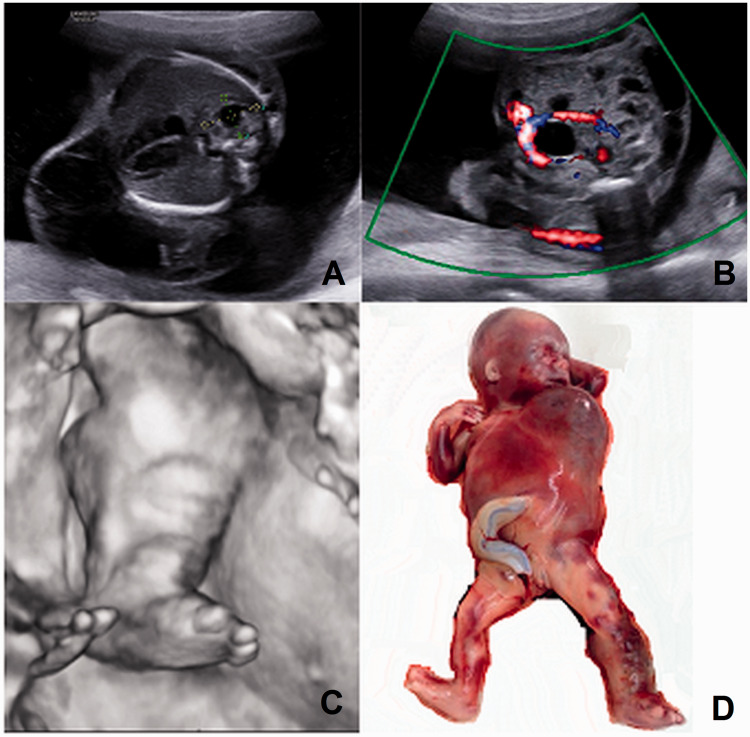

A 21-year-old primigravida was referred to our department due to “right-sided diaphragmatic hernia and cystic hygroma” of the foetus. At 20 weeks, we found a cystic structure 64 × 27 × 40 mm with little blood flow signals predominantly along the left half of the thorax, spreading on from the left axillary region to the torso, abdomen, both buttocks and the whole left leg including the toes (Figure 1(a) and (c), Supplemental Video 1). The left leg was enlarged because of numerous subcutaneous sonolucent multiloculated cystic lesions. A cystic and solid mass 15 × 12 × 12 mm was in the right lung, without detectable blood flow signals (Figure 1(a)). Amniotic fluid was increased. Mixed lesions, 6 to 13 mm in diameter, having both anechoic and echogenic areas with some blood flow were present in the low abdomen (Figure 1(b)). The family opted to terminate the pregnancy without further autopsy (Figure 1(d)).

Figure 1.

Case 1. (a) Cystic structure predominantly along the left half of the thorax and mixed structure (between callipers) in the right lung. (b) Colour mode: cystic and solid structures in the lower abdomen without detectable blood flow signals (velocity range 8 cm/s). (c) Three-dimensional mode: enlarged left leg. (d) Abortus phenotype. Note the purple stains, predominantly affection of the left side of the thorax and torso and the swollen enlarged left lower limb.

Case 2

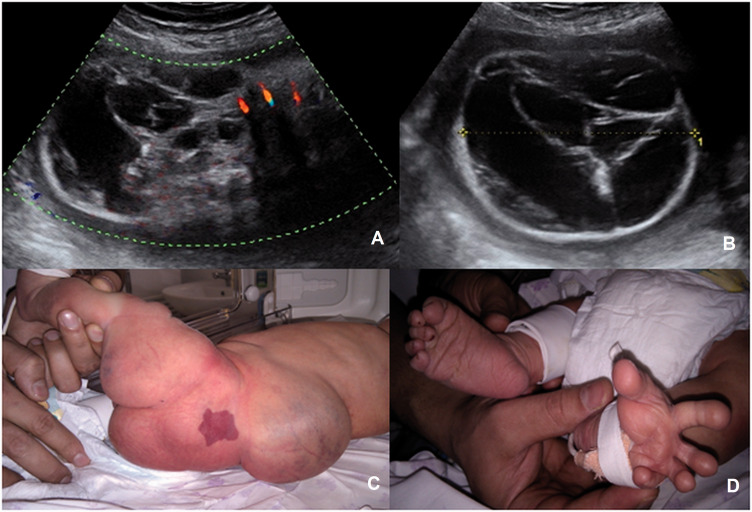

A 36-year-old woman (G5P2A2) was sent to our department with referral diagnosis “Spina bifida”. At 32 weeks, we revealed a 90-mm cystic and solid mass with single colour Doppler signals bridging the lumbar region (Figure 2(a) and (b)). The left buttock and thigh were markedly increased in size because of multiple cystic structures. Abnormal disposition of the toes was noted. At 39 gestational weeks, spontaneous delivery began and 3750 g, 53-cm male newborn was delivered with Apgar score 8–9. There were port wine stains on the right side of the body, face and the left thigh. The ultrasound findings were confirmed (Figure 2(c) and (d)). On the second day of the life, the Kasabach–Merritt syndrome developed and two days later baby died due to severe coagulopathy and cardiac failure.

Figure 2.

Case 2. (a,b) Mixed-structured mass of the lumbar and buttock region. (a) Colour mode (velocity range 17 cm/s). (b) B-mode. (c,d) Phenotype of the newborn. (c) Appearance of the affected limb, buttock and back. (d) Abnormal placement of the toes.

Case 3

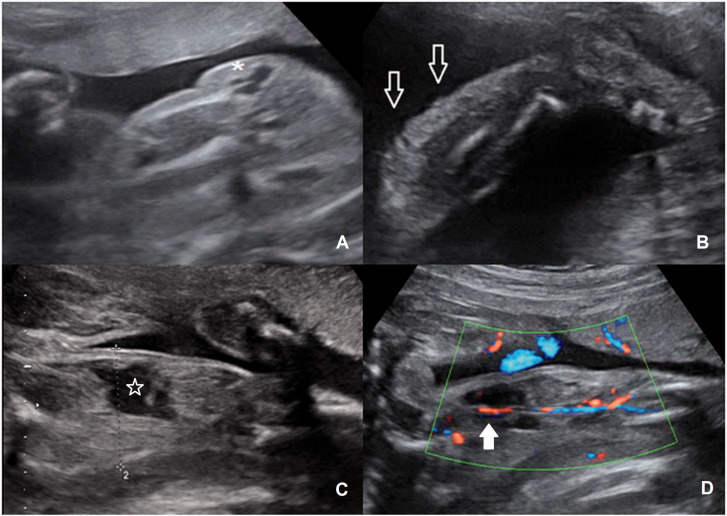

At the routine second trimester scan of the 31-year-old woman (G2P1A0), a small cyst in the foetal pelvis was revealed. Three weeks later, it become larger and patient had been referred to our department. At 24 weeks, aside from the cystic lesion in the low abdomen, small cystic lesions on the left buttock, thigh and calf were also identified (Figure 3(a) and (b), Supplemental Videos 2 and 3). There was a small asymmetry between lower limbs. Ten days later, the left leg increased in size, the cystic lesions became bigger and spread along the whole limb. In the left thigh, a hypoechoic structure of irregular shape with low resistant blood flow was revealed. This structure was considered to be a dilated varicose vein or vascular lacuna (Figure 3(c) and (d)). Due to the progression of the symptoms, the family opted to terminate the pregnancy. The post-mortem examination revealed the asymmetry of the affected limb and buttock compared with the normal one, vein varicosities and multiple small port wine stains of the affected limb.

Figure 3.

Case 3. (a) The cystic lesion of the left buttock (*). (b) The subtle superficial lesions of the left calf (arrows). (c,d) The affected thigh with hypoechoic structure of irregular shape (star) in B- and Colour mode. Note the femoral artery and vein (white arrow) (velocity range 8 cm/s).

Case 4

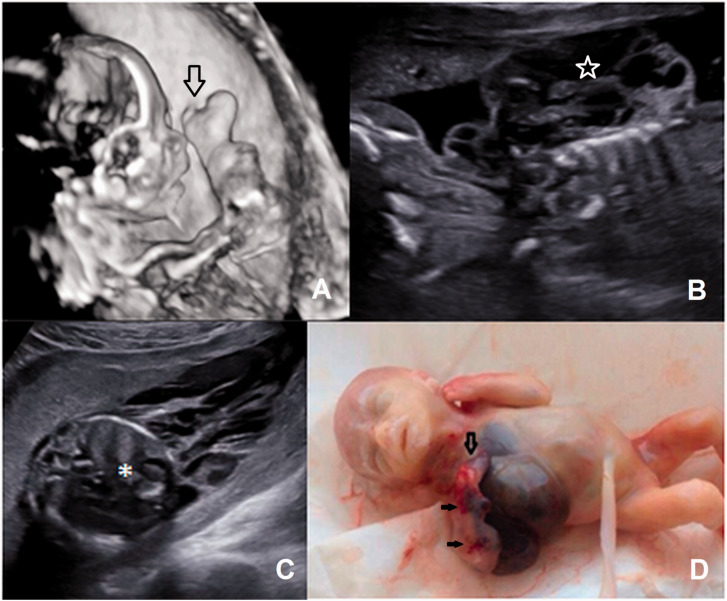

A 31-year-old woman (G7P2A4) was sent to our unit with diagnosis “tumour of the right surface of the chest wall”. At 20 weeks, a mixed cystic and solid structure 60 × 40×46mm was revealed along the right half of the thorax spreading on the right arm (Supplemental Video 4). The left arm and the lower limbs were not affected. In the right lung, there was a mixed structure with irregular shape without blood flow. The right shoulder and the forearm were affected by multiple cystic structures with single loci of low resistant blood flow. There was ectrodactyly of the right hand (Figure 4). Additional finding included hyperechogenic bowels and ascites. The family opted for termination of the pregnancy, but refused the autopsy.

Figure 4.

Case 4. (a) Three-dimensional mode: the affected limb with multiple cystic structures and ectrodactyly of the hand (arrow). (b) B-mode: the mixed structure in the right axillary region (star). (c) Cystic mass in the right axillary and thorax region and lung lesion (*). (d) Abortus phenotype. Note the ectrodactyly of the hand (arrow) and multiple small teleangiectasis (black arrows).

Review of the literature produced 33 additional cases, summarised in Table 1.3–33 Male to female ratio was 1:1. The median maternal age was 28.7 years (range 17–41). The median gestational age at abnormal ultrasound findings was 23 weeks (range 14–35).

The most frequent referral diagnosis was “oedema/anomaly of the body surface and/or limb” (13 cases, 39.4%). In four cases, there was a suspicion of “teratoma”. Six more patients were referred to the second opinion due to the non-specific findings (cardiomegaly, hydrops, ascites) or other reasons (suspected uterine fibroids, elevated alpha-fetoprotein level, unclear gestational age). The rare referral diagnoses included anterior wall defect, intestinal obstruction, parasitic twin and thoracic cyst. In seven cases, the reason for US-examination was “routine scan” or was not reported. Diagnosis of KTS was made prenatally in 24 out of 33 cases (72.7%), and in nine cases the final diagnosis was made only after birth (six cases) or pregnancy termination (three cases).

KTS was unilateral in 24 foetuses (72, 7%), bilateral in 7 (21.2%) and crossed-bilateral in 2 (6.1%), with both upper and lower limb involvement in three patients (9.1%). There was no difference between left or right affected side of the foetus. Hand/foot anomalies were noted in seven cases (21.2%).

Internal lesions were noted in 15 cases (45.5%) and affected intestines, liver, pericardium, kidneys and retroperitoneal space. In one case was reported about haemangiomas in testes and adrenal glands. Three foetuses had ventriculomegaly and two babies had cataracts. Among the additional findings were polyhydramnios, anasarca, ascites, hydrops, thickened placenta, cardiomegaly, hepatomegaly, pleural effusion, oligohydramnios, umbilical cord haemangioma.

Thirteen out of 33 patients (39.4%) opted to terminate the pregnancy. In one case, outcome was not reported. Among the 19 newborns, 8 babies (42.1%) died during the first 15 days post delivery. Among the other eleven babies, two (18.2%) required surgical treatment, one (9.1%) had conservative treatment and six needed only observation (54.5%). In two babies, the management strategy was not described.

Discussion

KTS or angioosteodystrophy syndrome was described by Klippel and Trenaunay in 1900 as a complex of cutaneous haemangiomas, varicose veins and hypertrophy of soft tissues and bones affecting one or more extremities. In 1907, Weber additionally described the case with arteriovenous fistula.34 The term “Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome” was once used to describe patients with features of KTS along with arteriovenous fistulas, when this in fact represented a distinct disorder now called Parkes–Weber syndrome.1

The aetiology of the disease remains unknown. Most cases of KTS occur sporadically and are not associated with the presence of large chromosomal abnormalities. However, there are some publications about reciprocal translocation t(5;11)(q13.3;p15.1), de novo translocation t(8;14)(q22.3;q13), variants of familial occurrence and autosomal recessive inheritance or autosomal dominant type of inheritance with incomplete penetrance.35 At the moment, a monogenic defect involved in the development of KTS is not clearly identified. Recent studies showed that most cases of KTS analysed genomically were found to be caused by mosaic-activating mutations in the PIK3CA gene at the long arm of chromosome 3.36 Among the reviewed cases, there was only one report about a prenatal diagnosis of KTS in a patient who had KTS herself as well as her eldest baby.12

The pathogenesis of the disease remains unclear. Some theories suggest a disturbance of mesoderm formation during embryonic development. This leads to the persistence of the embryonic type of the vasculature which can results in vascular anomalies in KTS. Other authors believe that formation of the disease is caused by an abnormal production or damaged regulation of growth factors (probably due to somatic mutation) necessary for the angiogenesis processes.23

KTS occurs with the same frequency in males and females. Its clinical presentation varies from minimally symptomatic disease to life-threatening bleeding and embolism.36 KTS may be unilateral (85% of patients), bilateral (12.5%) or crossed-bilateral (2.5%), with both upper and lower limb involvement in 10% of patients.37 Most often affected limb is lower extremity. However, KTS may affect the upper limbs and the surface of the trunk.38 Skin capillary malformations and hypertrophy of the limbs are usually present at birth, while venous anomalies may appear later in infancy. An atypical hypotrophic variant of KTS has also been described.36 Additionally, limb anomalies (polydactyly, macrodactyly, syndactyly, camptodactyly, ectrodactyly, hypoplasia and aplasia of the fingers) may also occur.37,39

The first case in utero manifestation of KTS was reported by Hatjis et al.,3 while fist prenatal diagnosis of this syndrome was made by Warhit et al.4 Since then less than 50 prenatally diagnosed cases of this pathology have been described.

Usually, KTS is diagnosed in the second half of pregnancy; however, there are reports about diagnosis of KTS at 17–20 weeks' gestation.10–13,16–17,20 The earliest in utero manifestations were described by Meizner et al. at 14 weeks.14 The earliest prenatal diagnosis was made by Shih et al.18 at 15 weeks.

The main ultrasound signs of KTS are haemangiomas affecting one or more extremities, soft tissue hypertrophy of the affected limb and involvement of the trunk (however, the latter is less common and not always diagnosed in utero).40 Less frequently noted involvement of the scalp and neck. Additional findings includes ventriculomegaly, cataracts, cardiomegaly, hydrops, polyhydramnios, thickening of the placenta, oligohydramnios.8,15–17,26,30,33 With the increasing gestational age, the haemangioma growth spreads to the trunk, new tumours appear (including tumours in the abdomen and chest), and hypertrophy of the affected limb develops.40

The combination of KTS with hand and foot defects is well known with split hand malformation being the rarest one. Redondo et al. described 51 patients with KTS at the age of 9–44 years, 17 of which had abnormalities of the hand and/or foot, but only one out of 51 patients had an ectrodactyly of the affected hand.37 Among prenatally revealed cases of KTS, hand/foot defects were noted only in four patients from 33 (12.1%). Three more cases were detected after birth,6,9,23 probably due to the minimal prenatal changes of the affected limbs. Foot anomalies included hypoplasia of the foot,14 hypoplastic thumbs,9 hypertrophy, macrodactyly, syndactyly of the toes and talipes equinovarus.28,30,31 Hand defects included syndactyly, hypoplastic fingernails, macrodactyly and abduction of the thumb.9,30,31 We described a prenatally revealed combination of KTS and ectrodactyly of the hand (Case 4) which has not been previously reported in foetuses.

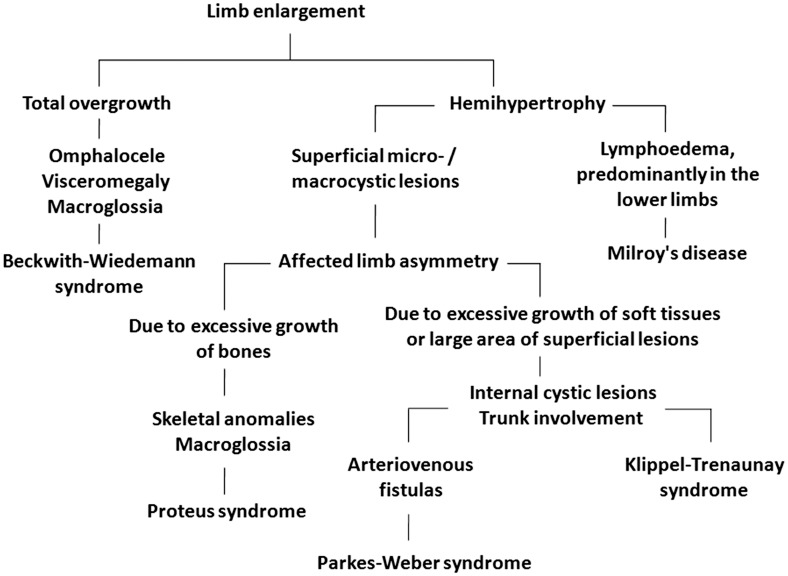

Differential diagnosis should be made with lymphangioma, cystic hygroma, hereditary lymphoedema (Milroy's disease), Beckwith–Wiedemann, Proteus and Parkes–Weber syndromes. Lymphangiomas are often single and localised, while haemangiomas in KTS are massive, multiple and affect a large area.40

Hypertrophy and hyperplasia of bones and soft tissues also occurs in the Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome (OMIM 130650), but these changes are symmetrical and affect the whole baby. The other features of this syndrome – omphalocele and macroglossia – were not reported in KTS patients to date.38

Proteus syndrome (OMIM 176920) is characterised by hemihypertrophy, macroglossia and the presence of superficial lymphangiomas. The most frequent manifestations of Proteus syndrome are changes in the musculoskeletal system and include kyphoscoliosis, macrodactyly, vertebral body anomalies and asymmetric growth of the affected limb associated with excessive growth of bone and muscle tissue. However, the localisation of superficial lesions over a large area, the lack of true hemihypertrophy, and the detection of port wine stains in the post-partum period allow to make a KTS diagnosis.38

Clinical manifestations of the syndrome of KTS are similar to those in Parkes–Weber syndrome, but in the latter case, arteriovenous fistulas are detected, which help to differentiate these syndromes.34,40 Prenatal ultrasound algorithm of differential diagnosis is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome diagnostic flowchart.

According to Oduber et al., KTS is characterised by two main groups of features39:

- A. Congenital vascular anomalies

- Capillary (port wine stains)

- Venous (hypoplasia/aplasia of veins, persistent embryonic veins)

- Lymphatic

- B. Changing limb sizes

- Hypertrophy

- Hypotrophy.

For the diagnosis of KTS, it is necessary to have at least one of the characteristics from group A (including A1 or A2) and one from group B. Despite such a detailed system, the diagnosis of KTS is not always simple. In the prenatal period, KTS can mimic the other pathological conditions, such as tumour, parasitic twin,5 sacrococcygeal teratoma11 or even bowel obstruction.24

One of the main features of the KTS is the abnormal structure of the limb venous system, which is noted in more than half of patients. It appears as a varicose enlargement, presence of persistent embryonic lateral marginal vein (or sciatic vein, also known as the vein of Servelle), hypoplasia or aplasia of the limb venous system.18,40 However, it is rather difficult to reveal these vascular changes prenatally. According to our knowledge, there is the only one publication by Coombs et al. about prenatal diagnosis of lower limb veins hypoplasia in the foetus.28

In most cases of KTS, the prognosis for life is favourable because after birth haemangiomas tend to decrease.40 However, the size of masses and their growth rate are very important. Thus, in our Case 3 the symptoms progressed from the single cystic lesion in the pelvis at 20 weeks to the multiple superficial lesions of the whole limb at 24 weeks and marked limb asymmetry 10 days later.

The large and extensive haemangiomas increase the risk of intrauterine heart failure development and the risk of bleeding in the postnatal period due to the development of severe thrombocytopenia.23,26 The latter is associated with the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation and haemolysis in haemangiomas (Kasabach–Merritt syndrome).33 Among reviewed case series, the Kasabach–Merritt syndrome was present in 31.5% of cases (6 of 19 newborns) with one of them developed prenatally.

The other prenatal complications of KTS (poly- and oligohydramnios, cardiomegaly, ascites, pleural effusion, hydrops) could be absent at the moment of the diagnosis and appears later in pregnancy. So the repeated US-scans of the foetus are needed to evaluate foetal condition and timely determinate the term and the mode of delivery. There are no unified recommendations about follow-up intervals in foetuses with KTS. They vary in every patient and depend on gestational age, the extent of the lesions and internal organ involvement.

The health prognosis in patients with KTS is unfavourable. Life quality of patients with KTS remains unsatisfactory because of the large number of complications. These include pain, discomfort, erysipelas, dermatitis, trophic ulcers, venous insufficiency, thrombosis, pulmonary embolism. Limb hypertrophy leads to the impairment of its function, length changes and scoliosis development.2,36

Management of KTS includes careful diagnosis, prevention and treatment of complications. The treatment can be conservative (compression stocking, analgesics, anticoagulants, antibiotics – in case of ulceration and cellulitis) and surgical (sclero-, laser or radiotherapy).2 With recurrent bleeding, infection or non-healing ulcers, limb amputation is performed. Christenson et al. described the case of KTS complicated by the development of the Kasabach–Merritt syndrome shortly after birth, which required amputation of the affected leg.15

Additionally, there are could be lesions of the genitourinary system (even in the absence of venous anomalies of the lower limbs) causing vascular compromise of the bladder or genital organs which can lead to haematuria. In massive haematuria, such patients need radical cystectomy and urinary diversion. Involvement of the gastrointestinal tract includes vascular malformations of mesentery, small and large intestine, enlargement of haemorrhoidal veins, complicated by gastrointestinal bleeding. Uncontrolled bleeding may be an indication for resection of affected areas of the intestine.2

Thus, timely prenatal diagnosis of KTS is very important. However, the prenatal manifestations of this syndrome can be minimal and extremely variable. Therefore, when multiple surface masses of the limbs and/or trunk of the foetus or cystic lesions of the internal organs with unclear aetiology are revealed on prenatal ultrasound scan, KTS should be included in the differential diagnoses and follow-up exams performed. Such approach provides the family the opportunity to decide whether to continue the pregnancy and also allows to adjust the extend of medical care for the newborn in every particular case.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

None.

Contributors

OI wrote the first draft of the manuscript, reviewed the literature, analysed patient data and wrote the final version. OI, EA and NO contributed with case reports. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval

This research was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Moscow Regional Research Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JRB #06004245).

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Guarantor

OI.

Patient consent

Written permission was obtained from the patients for publishing the photographs and images in this case report.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Volz KR, Kanner CD, Evans J, et al. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: need for careful clinical classification. J Ultrasound Med 2016; 35: 2057–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sreekar H, Dawre S, Petkar KS, et al. Diverse manifestations and management options in Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: a single centre 10-year experience. J Plast Surg Hand Surg 2013; 47: 303–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatjis CG, Philip AG, Anderson GG, et al. The in utero ultrasonographic appearance of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1981; 139: 972–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warhit JM, Goldman MA, Sachs L, et al. Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome: appearance in utero. J Ultrasound Med 1983; 11: 515–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seoud M, Santos-Ramos R, Friedman JM. Early prenatal ultrasonic findings in Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome. Prenat Diagn 1984; 4: 227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis BD, Doubilet PM, Heller VL, et al. Cutaneous and visceral hemangiomata in the Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome: antenatal sonographic detection. Am J Roentgenol 1986; 147: 598–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shalev E, Romano S, Nseir T, et al. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: ultrasonic prenatal diagnosis. J Clin Ultrasound 1988; 16: 268–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mor Z, Schreyer P, Wainraub Z, et al. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis associated with angioosteohypertrophy (Klippel–Trenaunay) syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988; 159: 1185–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drose JA, Thickman D, Wiggins J, et al. Fetalechocardiographic findings in the Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome. J Ultrasound Med 1991; 10: 525–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heydanu R, Wladimiroff JW, Brandenburg H, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome: a case report. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1992; 2: 360–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi M, Kurishita M, Sodemodo T, et al. Prenatal ultrasonic appearance of the Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome mimicking sacrococcygeal teratoma with an elevated level of maternal serum hCG. Prenat Diagn 1993; 13: 1162–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorgenson RJ, Darby B, Patterson R, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of the Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome. Prenatal Diagn 1994; 14: 989–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yankowitz J, Slagel DD, Williamson R. Prenatal diagnosis of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome by ultrasound. Prenat Diagn 1994; 14: 745–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meizner I, Rosenak D, Nadjari M, et al. Sonographic diagnosis of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome presenting as a sacrococcygeal mass at 14 to 15 weeks' gestation. J Ultrasound Med 1994; 13: 901–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christenson L, Yankowitz J, Robinson R. Prenatal diagnosis of Klippel–Trénaunay–Weber syndrome as a cause for in utero heart failure and severe postnatal sequelae. Prenat Diagn 1997; 17: 1176–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paladini D, Lamberti A, Teodoro A, et al. Prenatal diagnosis and hemodynamic evaluation of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1998; 12: 215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts RV, Dickinson JE, Hugo PJ, et al. Prenatal sonographic appearance of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome. Prenat Diagn 1999; 19: 369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shih JC, Shyu MK, Chang CY, et al. Application of the surface rendering technique of three-dimensional ultrasound in prenatal diagnosis and counselling of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome. Prenat Diagn 1998; 18: 298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeanty P. Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome, https://sonoworld.com/TheFetus/page.aspx?id=422 (1999, accessed 12 December 2018).

- 20.Mejia CAE, Ramirez J, Medina O, et al. 2000. Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome, https://sonoworld.com/TheFetus/page.aspx?id=423 (2000, accessed 25 September 2019).

- 21.Goncalves LF, Rojas MV, Vitorello D, et al. Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome presenting as massive lymphangiohemangioma of the thigh: prenatal diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2000; 15: 537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin WL, Ismail KM, Brace V, et al. Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber (KTW) syndrome: the use of in utero magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a prospective diagnosis. Prenat Diagn 2001; 21: 311–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zoppi MA, Ibba RM, Floris M, et al. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome with cardiac failure. J Clin Ultrasound 2001; 29: 422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assimakopoulos E, Zafrakas M, Athanasiades A, et al. Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome with abdominal hemangiomata appearing on ultrasound examination as intestinal obstruction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 22: 549–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahinoglu Z, Uludogan M, Delikara NM. Prenatal sonographicdiagnosis of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome associated with umbilical cord hemangioma. Am J Perinatol 2003; 20: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng HH, Wang TH, Chao AS, et al. Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome involving fetal thigh: prenatal presentations and outcomes. Prenat Diagn 2006; 26: 825–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen CP, Lin SP, Chang TY, et al. Prenatal sonographic findings of Klippel–Trénaunay–Weber syndrome. J Clin Ultrasound 2007; 35: 409–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coombs PR, James PA, Edwards AG. Sonographic identification of lower limb venous hypoplasia in the prenatal diagnosis of Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 727–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volkov A, Matsionis A, Voloshin V, et al. Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome, https://sonoworld.com/TheFetus/page.aspx?id=2639 (2009, accessed 25 September 2019).

- 30.Al-Asali O, Abo-Almaged I, Al Taher A, et al. Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome case of the week #286, https://sonoworld.com/TheFetus/case.aspx?id=2861 (2011, accessed 25 September 2019).

- 31.Horenstein M. Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome, https://sonoworld.com/TheFetus/page.aspx?id=3026 (2011, accessed 25 September 2019).

- 32.Cakiroglu Y, Doğer E, Yildirim Kopuk S, et al. Sonographic identification of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2013; 2013: 595476 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka K, Miyazaki N, Matsushima M, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome with Kasabach–Merritt syndrome in utero. J Med Ultrasond 2015; 2: 109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lacerda LDS, Alves UD, Zanier JF, et al. Differential diagnoses of overgrowth syndromes: the most important clinical and radiological disease manifestations. Radiol Res Pract 2014; 2014: 947451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Q, Timur AA, Szafranski P, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of de novo translocation t(8;14)(q22.3;q13) associated with a vascular and tissue overgrowth syndrome. Cytogenet Cell Genet 2001; 95: 183–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frieden I and Chu D. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management, www.uptodate.com/contents/klippel-trenaunay-syndrome-clinical-manifestations-diagnosis-and-management (2017, accessed 18 January 2018).

- 37.Redondo P, Aguado L, Martinez-Cuesta A. Diagnosis and management of extensive vascular malformations of the lower limb. Part I. Clinical diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65: 893–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones KL, Jones MC and Del Campo M. Smith's recognizable patterns of human malformation. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2013, pp.672–673.

- 39.Oduber CE, Van Der Horst CM, Hennekam RC. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: diagnostic criteria and hypothesis on etiology. Ann Plast Surg 2008; 60: 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paladini D, Volpe P. Ultrasound of congenital fetal anomalies/differential diagnosis and prognostic indicators, 2nd ed Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.