Dear Editor,

We read with interest the letter from Hao et al highlighting the issues regarding the sensitivity of real time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing of upper respiratory tract samples for COVID19 disease [1]. Extensive RT-PCR testing by has been key to clinical decision-making, epidemiological analysis and policy development during the current severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic. The majority of RT-PCR assays target the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), envelope protein (E) or nucleocapsid protein (N) genes [2]. However, initial testing algorithms and expert opinion from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) advised that E gene amplification in isolation should be treated cautiously, due to concerns of non-specificity and issues related to contamination of reagents [3]. Early experience at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UK) on serially sampled patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection suggested that E gene detection persists beyond RdRp detection, and may offer enhanced diagnostic sensitivity. Therefore we explored the significance of E gene detection in relation to RdRp, and in the absence of RdRp detection in a retrospective evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing.

A total of 12,015 clinical samples (combined nose/throat swabs or lower respiratory tract samples) were tested for SARS-CoV-2 as part of routine clinical diagnostics between 2nd March 2020 and 5th April 2020 at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Samples were extracted on the MagnaPure96 platform (Roche Diagnostics Ltd, Burgess Hill, UK). SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected on 6µl of extract using a dual target (E gene and the RdRp gene) in-house PCR on ABI Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, United States) (supplementary material) [4]. The assay was modified to a multiplex single-well assay with the addition of PCR primers to detect a housekeeping gene, Ribonuclease P (RNAse P), which acts as an internal control and to assess sample quality.

Of the samples tested, 2,593 samples (21.6%) were positive with amplification curves for one or both target genes. Amongst positive results, we found E gene amplification alone to be common (n= 319, 12.3%), although the majority were positive for both RdRp and E gene targets (n = 2273, 87.7 %) and only 1 sample (<0.1 %) had RdRp gene amplification alone.

From the E-only positive group (n=319), 69 (21.6%) samples had low level amplification in the E gene (cycle threshold (CT) ≥35) and were investigated further. Within this subset, the majority (n=59, 85.5%) were considered to be true positives because they were either a) confirmed by an alternative assay (n=48) or b) a preceding or subsequent sample was positive for both E and RdRp (n=11) (Table 1 ). The alternative assay employed was a modified version of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) assay targeting the N gene (Micropathology Ltd, Coventry, UK) in most cases (n=47) or an alternative RdRp assay (n=1) [7]. Six samples (8.7 %) could not be confirmed in an alternative assay which had either high CT values for the E gene (n=4, CT values ≥39.0) or had good amplification curves not reaching the threshold (n=2). To further confirm the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in samples with E gene only amplification, 11 samples were selected and successfully underwent whole genome sequencing (supplementary material). Analysis of the RdRp primer or probe binding sites in these samples did not reveal any mismatches to explain the lack of RdRp RT-PCR positivity (supplementary material).

Table 1.

Summary of samples with low level E gene amplification alone (CT ≥ 35). CT, cycle threshold; E, envelope gene.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sent for confirmation at reference laboratoryɸ | 54 | 78.26 |

| Confirmed by alternative assay | 48 | (88.89) |

| Not confirmed | 6 | (11.11) |

| Repeat clinical sample positive | 5 | 7.25 |

| Previous clinical samples positiveψ | 6 | 8.70 |

| Resulted without further testingǂ | 4 | 5.80 |

| Total | 69 |

Most samples (n=53) were tested at Micropathology Ltd (Coventry) using a SARS-CoV-2 N gene assay using a modified CDC assay [6]. The other sample confirmed positive at PHE Colindale using an alternative SARS-CoV-2 RdRp assay.

As part of the High Consequences Infectious Diseases network, Sheffield received some of the first positive patients in the United Kingdom, who had daily swabs taken. E gene amplification appeared to persist in this cohort after the RdRp became negative.

Four results were authorised without further testing due to high pre-test probability e.g. compatible symptoms with a confirmed household exposure to SARS-CoV-2.

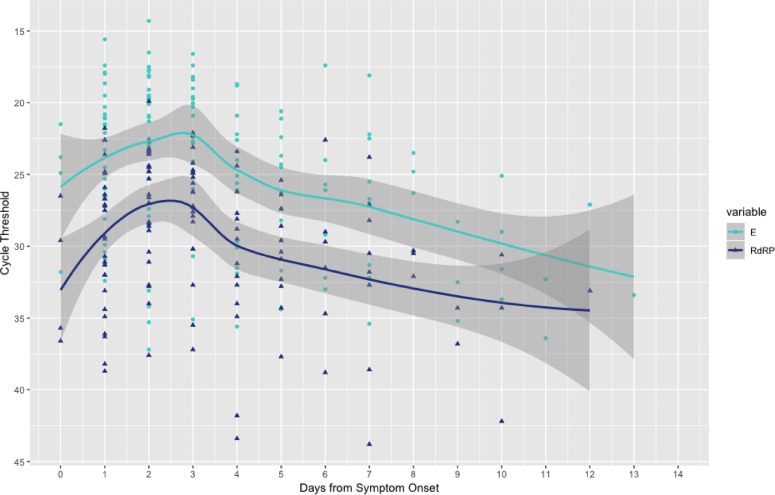

We further explored the relationship between E gene detection and RdRp gene detection. Amongst samples with both RdRp gene and E gene amplification (n= 2273), we found that CT values for the E gene target were significantly lower than the CT values for RdRP, with a mean difference of 5.8 (Paired t test, p-value < 2.2e-16, 95% CI 5.79-5.92) (supplementary material). In a subset of samples where symptom onset was available (145 samples from 128 patients), it was clear that the CT values for both RdRp and E gene were lowest around 48 – 72 hours following symptom onset (Fig. 1 ). At each stage of infection, the median CT values for RdRp were higher than those for the E gene.

Fig. 1.

E and RdRp gene cycle threshold results in relation to symptom onset. E and RdRp amplification results plotted against days of symptom onset in 145 samples from 128 patients. Lowest CT values were seen around day 3 of symptoms, with mean RdRp CT higher at a given day compared to E gene CT value. The lines represent the smoothed conditional mean with 95% confidence intervals in the grey bars. E, envelope gene; RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase.

By using the E gene target in addition to the RdRp gene target we observed a significantly increased diagnostic pick up (11.9%). In one patient, E gene amplification was detected for three days beyond RdRp amplification, indicating a possible widening of the diagnostic window. Our findings confirm that clinical samples with E only amplification should not be dismissed as non-specific results. Not only were we able to obtain whole genome sequences for SARS-CoV-2 from a subset of this group, we also found that 85% of E only samples with high CT values were confirmed by a second assay targeting the N gene or an alternative RdRp only assay.

The enhanced sensitivity seen for the E gene in our dual target E-RdRP assay is yet to be explained. We observed a mean difference of over five CT values when comparing E gene to RdRp values, which may suggest the possibility of higher copy numbers of E gene being present in the primary or extracted sample. Due to the unique transcription strategy of coronaviruses, genes towards the 3’ end of the genome would be present in higher copy numbers during active viral replication, which could explain these findings [5]. It is also possible that PCR optimised conditions in a multiplex system favours E gene amplification, however we found no significant loss of RdRp detection when comparing single and multiplex systems during validation, with observed CT rises averaging 1-2 cycles (data not shown). In addition, we found no evidence of primer or probe mismatches in the RdRp region.

We believe dual target testing, using the E gene as a second target, will help improve both diagnostic sensitivity and the appropriate clinical response to this pandemic. We urge testing laboratories to carefully consider the use of the E gene as a target in order to optimise SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics, including strategies to confirm samples with E gene only amplification as we have described.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Virology team at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust for the long hours in the processing and testing of clinical specimens, and Professor Goura Kudesia for her contribution towards assay validation work. We would also like to thank Andy Taylor at Micropathology Laboratories, Coventry for sharing the N gene data. Sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 samples was undertaken by the Sheffield COVID-19 Genomics Group as part of the COG-UK CONSORTIUM. The sequencing part of the validation was in part supported / funded by the NIHR Sheffield Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.061.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Hao W, Li M. Clinical features of atypical 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia with an initially negative RT-PCR assay. J Infect. 2020;80(6):671–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Udugama B, Kadhiresan P, Kozlowski HN. Diagnosing COVID-19: The Disease and Tools for Detection. ACS Nano. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c02624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Questions and answers regarding laboratory topics on SARS-CoV-2. Available at:https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/all-topics-z/coronavirus/threats-and-outbreaks/covid-19/laboratory-support/questions. Accessed 19th April.

- 4.Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawicki SG, Sawicki DL, Siddell SG. A contemporary view of coronavirus transcription. J Virol. 2007;81(1):20–29. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01358-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC. Real-time RT-PCR Primer and Probe Information. Available at:https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-panel-primer-probes.html. Accessed 19th April 2020.

- 7.https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/emergency-situations-medical-devices/emergency-use-authorizations#covid19ivd. Accessed 19th April 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.